Abstract

Background

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended as the primary treatment for advanced bladder cancer (BC) with unresectable or metastatic disease. However, the benefits are limited due to the acquisition of drug resistance. The mechanisms of resistance remain unclear. Although there are some reports that some molecules are associated with cisplatin resistance in advanced BC, those reports have not been fully investigated. Therefore, we undertook a new search for cisplatin resistance-related genes targeted by tumor suppressive microRNAs as well as genes that were downregulated in cisplatin-resistant BC cells and clinical BC tissues.

Methods

First, we established cisplatin-resistant BOY and T24 BC cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24). Then, Next Generation Sequence analysis was performed with parental and cisplatin-resistant cell lines to search for the microRNAs responsible for cisplatin resistance. We conducted gain-of-function analysis of microRNAs and their effects on cisplatin resistance, and we searched target genes comprehensively using Next Generation mRNA sequences.

Results

A total of 28 microRNAs were significantly downregulated in both CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24. Among them, miR-486-5p, a tumor suppressor miRNA, was negatively correlated with the TNM classification of clinical BC samples in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Transfection of miRNA-486-5p significantly inhibited cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and also improved the cells’ resistance to cisplatin. Among the genes targeted by miRNA-486-5p, we focused on enoyl-CoA, hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (EHHADH), which is involved in the degradation of fatty acids. EHHADH was directly regulated by miRNA-486-5p as determined by a dual-luciferase reporter assay. Loss-of-function study using EHHADH si-RNA showed significant inhibitions of cell proliferation, migration, invasion and the recovery of cisplatin sensitivity.

Conclusion

Identification of EHHADH as a target of miRNA-486-5p provides novel insights into the potential mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in BC.

Keywords: Cisplatin resistance, Bladder cancer, EHHADH, miR-486-5p

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) can be roughly classified into non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive BC (MIBC). Approximately 50% of MIBC patients develop metastasis within 2 years, and the 5-year survival rate remains under 50% [1]. Advanced BC patients are generally treated with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy [2]. Although the overall survival rate (OS) has been extended by cisplatin, the median OS is only about 14 months after cisplatin based-chemotherapy [3, 4]. Because the molecular mechanisms of resistance to cisplatin in BC remain unclear, studies of the mechanism and novel prognostic markers to overcome cisplatin resistance are needed to improve outcomes in patients with BC.

Pharmacologically, cisplatin goes through hydrolysis and avidly binds DNA through the N7-sites of either a guanine or adenine base. Crosslinks and damage to DNA result, and apoptosis is induced [5, 6]. However, cancer cells can be initially resistant to cisplatin or they can acquire resistance [7]. For example, the high-affinity copper transporter (CTR1) is involved in the intracellular uptake of cisplatin. Knockdown of CTR1 reduces the intracellular accumulation of cisplatin and induces cisplatin resistance [8]. Moreover, the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) induces cisplatin resistance [9, 10]. In spite of intense study of cisplatin resistance, it has not yet been overcome.

MicroRNAs are endogenous small non-coding RNA molecules (19 ~ 22 bases in length) that regulate the expression of protein-coding/protein non-coding genes [11]. Our previous studies showed that microRNAs play many roles in cancer, including cancer cell progression, migration and invasion, and some microRNAs have significant roles in human oncogenesis [12, 13]. microRNAs are involved in cisplatin resistance in lung, gastric tissue, colon and ovarian cancers [14, 15]. Yang et al. reported that the transfection of miRNA-214 into ovarian cancer cell lines suppressed PTEN, activated protein kinase AKT and led to cisplatin resistance [16]. In addition, Zhu et al. determined that miRNA-181b was downregulated in cisplatin-resistant lung cancer lines, and that miRNA-181b modulated cisplatin resistance by targeting the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2 [17]. In BC, the relationships between microRNAs and cisplatin resistance are poorly understood. Therefore, this study focused on the effects of microRNAs on cisplatin resistance.

In order to elucidate the mechanism of cisplatin resistance, we established cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24). Then, small-RNA sequence analyses were performed with the parental and resistant cell lines to search for the microRNAs associated with cisplatin resistance. The candidate microRNA was transduced into cisplatin-resistant cell lines for functional analysis. Next, we searched for target genes using RNA next-generation sequence analysis. We also performed loss of function studies to assess its target gene.

Methods

BC cell lines and culture

We used 2 human BC cell lines: BOY was established in our laboratory from a 66-year-old Asian male patient, who was diagnosed with BC stage IV with many lung metastases. T24 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Generation of CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24 is described in Fig. 1a. These cell lines were cultured in minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEME) containing 50 mL of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50 U/mL penicillin in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 at 37 °C. To establish CDDP-R BC cell lines, we cultured BC cell lines with serial concentrations of cisplatin from 0.01 to 2.0 μg/mL for 6 months. The cells were cultured in 10 mL of medium for 24–36 h containing 1 mL of cisplatin that had been adjusted to 10-times the target concentration.

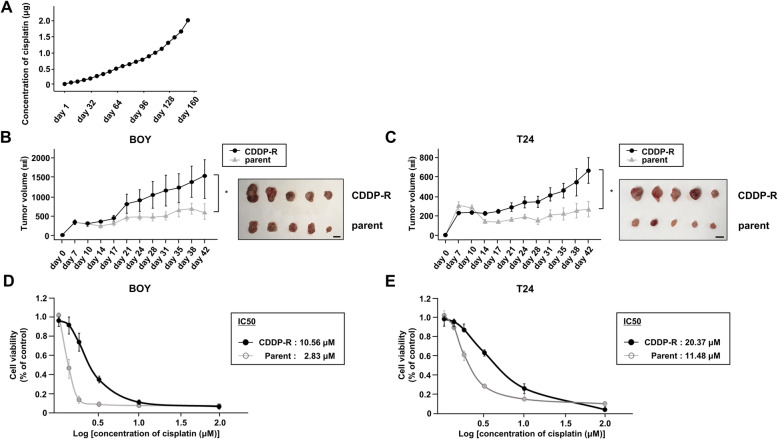

Fig. 1.

Establishment of cisplatin-resistant BC cells. a BC cells (BOY and T24) were cultured with serial concentrations of cisplatin from 0.01 to 2.0 μg/mL for 6 months. Time course comparing tumor volumes of (b) parental BOY/CDDP-R-BOY and (c) parental T24/CDDP-R-T24 after subcutaneous injection of cisplatin (4 mg/kg/mouse/week, n = 5 mice per group) *, P < 0.05. Scale bar: 10 mm. Calculated IC50 of (d) parental BOY/CDDP-R-BOY and (e) parental T24/CDDP-R-T24

Validation of the CDDP-R BC cell lines in vivo

The animal research described here was conducted in accordance with the regulations covering animal experiments at Kagoshima University, and the plan was approved by the Animal Experiment Committee at Kagoshima University (MD18094). We used 10 female athymic nude mice (BALB/c-nu/nu), aged 5 weeks, that were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Yokohama, Japan). Sample size was determined by the guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research [18]. Mice were maintained in a standard laboratory environment (12-h day/night cycle, temperature, 25 °C), using rectangular mouse cages (225 × 338 × 140mm). Two or 3 mice were housed per cage, and a total of 4 cages were used. The cages were lined with sawdust to ensure water absorption and flexibility, and mice had continuous access to water and a standard diet (CLEA Rodent Diet CL-2) and were cleaned once a week. We used CDDP-resistant cells (CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24) and their parental cells (BOY, T24) as controls. Four BC cell lines (BOY, CDDP-R-BOY, T24, and CDDP-R-T24) were adjusted to 1 × 107 /mL, and 100 μL of the BC cells and 100 μL of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) were mixed. We subcutaneously injected parental cells (BOY, T24) into the right flanks and CDDP-R cells (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24) into the left flanks in a volume of 200 μL (5 mice per group). The measurement of mouse body weight and tumor size was started 7 days after the inoculation and conducted twice a week. Tumor dimensions were measured with calipers and sizes were calculated by the following formula: v = (length × width2) × (π/ 6). The administration of cisplatin (4 mg/kg, 5 times/week) [19] also started 7 days after the inoculation. At the endpoint of the experiment (6 weeks after the inoculation) all mice were euthanized with high concentrations (90–100%) of isoflurane and the tumor sizes were evaluated. There were no criteria used for including or excluding animals during the experiment. There was no exclusion of any experimental units or any data points for any experimental group. No adverse events were observed. The statistical significance of the difference of tumor size between the groups was analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test using Expert StatView software, version 5.0 (Cary, NC, USA). P values less than 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. There were no confounders in the animal experiments. All animal experiments were conduced by SO, HY, KK, and MT.

IC50 determination

For determination of the IC50 value, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells per well in triplicate and treated with a series of dilute concentrations of cisplatin. After 96 h of incubation, cell proliferation was measured using the XTT assay method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A probit regression model was used to calculate the IC50 value using ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov) software.

Transfection with mature miRNA and small interfering RNA (siRNA)

BC cells were transfected with the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10 nM miRNA and siRNAs as previously reported [20]. Mature microRNA (hsa-miR-486-5p; product ID: PM10546) and negative-control microRNA (negative control miRNA; product ID: AM 17111) were used in gain-of-function experiments. EHHADH si-RNA (cat No. HSS105529 and HSS105531) and negative-control si-RNA (D-001810-10) were used in loss-of-function experiments.

MicroRNA and mRNA sequence analysis

To search for the microRNAs associated with cisplatin resistance, total RNAs extracted from BOY, CDDP-R-BOY, T24, and CDDP-R-T24 cell lines were subjected to microRNA sequencing, performed by RIKEN GENESIS CO., LTD., Tokyo, Japan. We compared parental and CDDP-R cell lines (BOY vs CDDP-R-BOY, T24 vs CDDP-R-T24), and selected miRNAs with significantly downregulated expression in the CDDP-R cell lines (fold-change < − 1.0). mRNA sequence analysis was performed by RIKEN GENESIS CO., LTD. to identify the target mRNA of miRNA-486-5p. For the samples, a TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit was used to create libraries, and Illumina Inc’s flow cell was used for sequencing. The valid read length was 150 bp, and the analysis was performed using a Multiplex method. Candidate target genes were significantly downregulated after transfection with miRNA-486-5p compared with control microRNA (fold-change < − 1.0) in CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24.

In silico analysis

In order to evaluate the clinical relevance of our findings, a TCGA cohort database of 413 patients with BLCA was used. This study follows the criteria for the publication guidelines provided by TCGA. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to analyze overall survival (OS) using data in the OncoLnc dataset (http://www.oncolnc.org/). To search for the miRNAs associated with cisplatin resistance, we identified miRNAs that were lower in expression in CDDP-R cells compared to parental cells in both BOY and T24, and had been reported as tumor suppressor genes. To identify possible target genes of miRNA-486-5p, we extracted genes that were reduced by transfection of miR486-5p in mRNA sequence analysis with genes that may be targeted by miRNA-486-5p based on TargetScan database Release 7.1 (http://www.targetscan.org).

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

To quantify the expression of miRNA-486-5p, we used Stem-loop RT-PCR (TaqMan MicroRNA Assays; P/N: 4427975 for miR-486-5p: Applied Biosystems) according to previously published conditions [20]. RNU48 (P/N: 001006; Applied Biosystems) was used as the internal control. With regard to EHHADH, we applied a SYBR-green quantitative PCR-based array approach. The primer set used for determination of EHHADH mRNA expression level was as follows: forward, 5′-AAACTCAGACCCGGTTGAAGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGCAGAGTCTACGGGATTCT − 3′. For glucuronidase β (GUSB; internal control), the set was as follows: forward primer, 5′-CGTCCCACCTAGAATCTGCT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TTGCTCACAAAGGTCACAGG − 3′. The specificity of amplification was monitored using the dissociation curve of the amplified product.

Western blotting

To prepare total protein lysates, we used NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunoblotting was carried out with diluted anti-EHHADH (1:500; cat. no. 13412–1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), anti-cleaved PARP antibodies (1:750, #5625; Cell Signaling Technology), PARP antibodies (1:750, #9532; Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-β-actin antibodies (1:5000; cat. no. bs-0061R; Bioss, Beijing, China). The secondary antibodies were peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; cat. no. 7074S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) or anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; cat. no. 7074S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The protein levels were evaluated using ImageJ software (ver. 1.48; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html) as described previously [21, 22].

Cell proliferation, migration, invasion assays, and apoptosis assays

To evaluate cell proliferation, we used XTT assays. T24 and BOY cells were seeded in 96-well plates with 2 × 103 cells/well with 100 μL of medium containing of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). We determined the extent of cell proliferation 96 h after seeding with a Cell Proliferation Kit II (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously. When using cisplatin, we added 10 μL adjusted to 10-times the target concentration. Wound healing assays were used for cell migration activity. Cells (2 × 105 per well) were plated in 6-well plates, and after 48 h of incubation, the cell monolayer was scraped using a P-20 micropipette tip. The initial gap length (0 h) and the residual gap length 24 h after wounding were calculated from photomicrographs. For cell invasion assays, we used modified Boyden chambers consisting of Matrigel-coated Transwell membrane filter inserts with 8 μM pores in 24-well tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The cells that had passed through the pores and attached to the surface of the chamber were counted from photomicrographs. For apoptosis assays, double staining with FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide was performed using a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX Analyzer; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). We classified cells in 4 categories: viable cells, dead cells, early apoptotic cells or apoptotic cells using Summit 4.3 software (Beckman Coulter). The sums of the percentages of early apoptotic and apoptotic cells were compared. The cells treated with 2 μg/mL cycloheximide were used as a positive control.

Plasmid construction and dual-luciferase reporter assays

Partial wild-type (WT) sequences of the 3′-UTR of EHHADH or those with a deleted miRNA-486-5p target site were inserted between the XhoI and PmeI restriction sites in the 3′-UTR of the hRluc gene in the psiCHECK-2 vector (C8021; Promega, Madison, WI, USA). CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24 cells were transfected with 50 ng of vector and 10 nM miRNA-486-5p. According to the manufacturer’s protocol (E1960; Promega), the activities of firefly and Renilla luciferases in cell lysates were determined with a dual luciferase assay system.

Results

Establishment of cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines

First, we established cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24). BC cells (BOY and T24) were cultured with serial concentrations of cisplatin from 0.01 to 2.0 μg/mL (Fig. 1a). The cells grew well in the presence of 2.0 μg/mL cisplatin. CDDP-R cells were continuously exposed to cisplatin for the maintenance of resistance [23, 24]. There was no significant difference in cell proliferation between the parental cells and CDDP-R cells in vitro (Supplementary Figure 1a). To validate drug resistance in vivo, we subcutaneously injected parental cells into the right flanks and CDDP-R cells into the left flanks of nude mice. The mice were treated with cisplatin intraperitoneally every other week [19]. The tumor growth of parental xenografts (BOY and T24) was reduced by intraperitoneal administration of cisplatin. In contrast, the CDDP-R tumors (CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24) were not suppressed, reflecting their resistance to cisplatin (Fig. 1b, c). To determine the extent of cisplatin resistance, we calculated the IC50 value. In the case of BOY, the IC50 of CDDP-R-BOY was 5-times greater than the IC50 concentration inhibiting BOY (BOY IC50: 2.83 μM, CDDP-R-BOY IC50: 10.56 μM); for CDDP-R-T24, it was twice that of T24 (T24 IC50: 11.48 μM, CDDP-R-T24 IC50: 20.37 μM) (Fig. 1d, e).

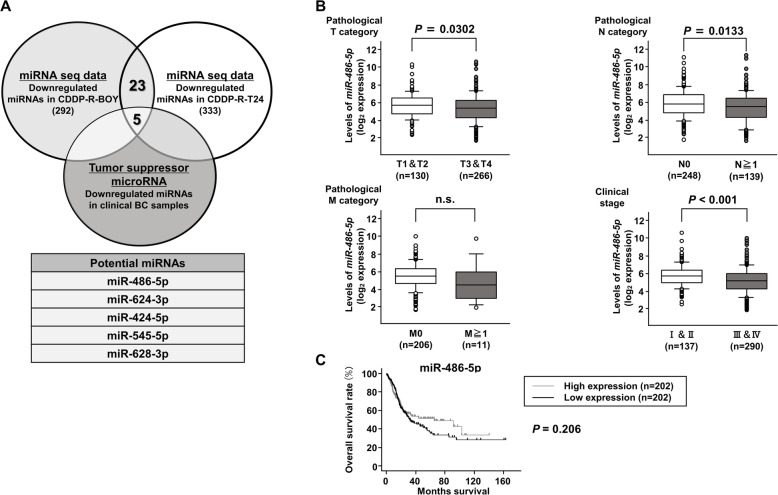

Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p in CDDP-R-BC cell lines and BC specimens

We performed microRNA sequence analysis of the parental and resistant cell lines to search for the miRNAs associated with cisplatin resistance. A total of 28 microRNAs were downregulated in both CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24 cell lines. We searched for tumor-suppressive microRNAs, comparing BC and normal bladder epithelia by using a dataset reported by Itesako et al. [25]. Ultimately, 5 microRNAs (miRNA-486-5p, miRNA-624-3p, miRNA-424-5p, miRNA-545-5p and miR-628-3p) were identified as candidates (Fig. 2a). Among the bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) cohort in TCGA, miRNA-486-5p and miRNA-545-5p showed significant difference between pathological category T1/2 vs T3/4. On the other hand, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that overall survival (OS) exhibited no significant difference between the high expression group and the low expression group in miRNA-486-5p and miRNA-545-5p (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Figure 2b). Because miRNA-545-5p transfection did not suppress cell proliferation in CDDP-R BC cells (data not shown) and there was no correlations between miRNA-545-5p and the target gene (Supplementary Figure 2c), we focused on miRNA-486-5p as a strong candidate tumor suppressor that could overcome cisplatin resistance in this study.

Fig. 2.

Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p in the CDDP-R-BC cell line and BC specimens. a Venn diagram of mRNA sequences and in silico analyses indicated 5 putative candidate miRNAs. b Among the BLCA cohort of TCGA, there were obvious negative correlations among expression levels of miRNA-486-5p and pathological T, N, and stage categories. c Kaplan-Meier analysis using the OncoLnc dataset revealed that there was a tendency for the high miRNA-486-5p expression group to have a lower OS than the low miRNA-486-5p expression group, but it did not reach significance (P = 0.206)

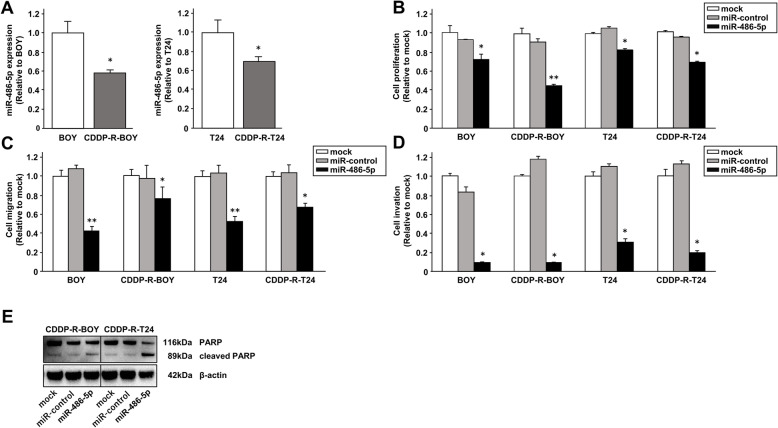

Effects of miRNA-486-5p restoration on cell proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis in CDDP-R-BC cell lines

First, we used qRT-PCR to confirm that expression of miRNA-486-5p was downregulated in CDDP-R BC cells compared with parental cells (Fig. 3a). We also performed gain-of-function studies of parental cell lines (BOY and T24) and CDDP-R cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24) transfected with miRNA-486-5p (Supplementary Figure 3a) to investigate the functional roles of miRNA-486-5p. Cell proliferation of both parental and CDDP-R BC cells transfected with miRNA-486-5p was significantly inhibited in the XTT assay in comparison with mock or microRNA-control transfected cells (Fig. 3b). Moreover, cell migration activity in wound healing assays and cell invasion in Matrigel invasion assays showed significant inhibition in the miRNA-486-5p transfectants compared to their counterparts (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Figure 3b, c). Because cisplatin induces apoptosis in cancer cells [5], we used Western blots to assess apoptosis. The expression level of cleaved PARP increased in miRNA-486-5p transfectants (Fig. 3e). Thus, miRNA-486-5p induced apoptosis in both parental and CDDP-R BC cells and provided anti-tumor effects.

Fig. 3.

Effects of miRNA-486-5p restoration on cell proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis in CDDP-R-BC cell lines. a Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p determined by qRT-PCR were significantly lower in cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines than in parental BC cell lines. *, P < 0.05. b Cell proliferation determined by XTT assay. *, P < 0.01; * *, P < 0.001. c Cell migration activity determined with wound healing assay. *, P < 0.01; * *, P < 0.001. d Cell invasion activity determined with Matrigel invasion assay. *, P < 0.001. e Western blot analysis of apoptotic markers (cleaved PARP and PARP) in CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 8.

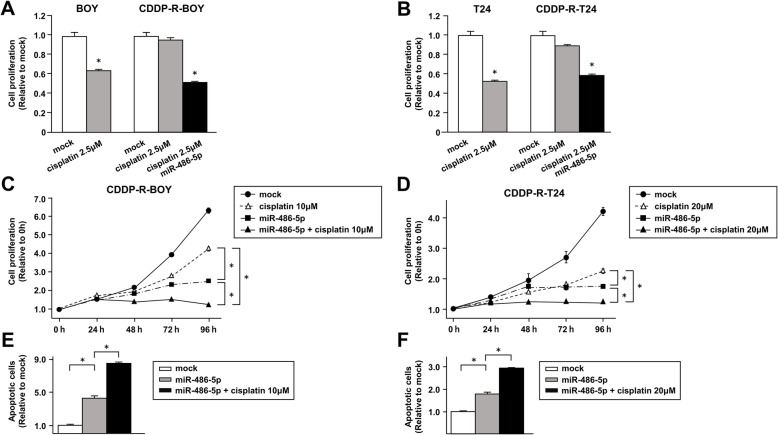

Transfection of miRNA-486-5p increased the sensitivity of CDDP-R-BC cell lines to cisplatin

As shown in Fig. 1c, cell viability was not suppressed in CDDP-R-BOY by treatment with 2.5 μM cisplatin, which is the IC50 concentration for BOY. However, by simultaneous miRNA-486-5p transfection, cell proliferation decreased to the level observed in parental BOY (Fig. 4a) at 2.5 μM cisplatin. Similar results were found with T24 (Fig. 4b). Next, we examined cell proliferation following cisplatin treatment and miRNA-486-5p transfection. We administered 10 μM cisplatin, which is the IC50 for CDDP-R-BOY. The combination of miRNA-486-5p transfection and cisplatin administration clearly had additive effects and significantly suppressed cell proliferation (Fig. 4c). We also administered 20 μM cisplatin to CDDP-R-T24 and obtained similar results (Fig. 4d). The combination of miRNA-486-5p transfection and cisplatin induced more apoptotic cells in flow cytometric analyses (Fig. 4e, f Supplementary Figure 4a). Thus, cell proliferation was suppressed and apoptosis was enhanced. These results suggested that miRNA-486-5p functioned as a tumor suppressor in CDDP-R cells and increased their sensitivity to cisplatin.

Fig. 4.

Transfection of miRNA-486-5p improves sensitivity to CDDP in CDDP-R-BC cell lines. The IC50 concentration of cisplatin was given to parental and cisplatin-resistant cells. Transfection of 10 nM miRNA-486-5p increased the cisplatin sensitivity in (a) CDDP-R-BOY and (b) CDDP-R-T24 cells as determined by XTT assay. *, P < 0.001. miRNA-486-5p transfection and cisplatin administration (IC50 dose) to (c) CDDP-R-BOY and (d) CDDP-R-T24 cells clearly had an additive effect and significantly suppressed cell proliferation. *, P < 0.001. e, f Apoptosis assays were carried out using flow cytometric analysis of CDDP-R-BC cells. *, P < 0.001

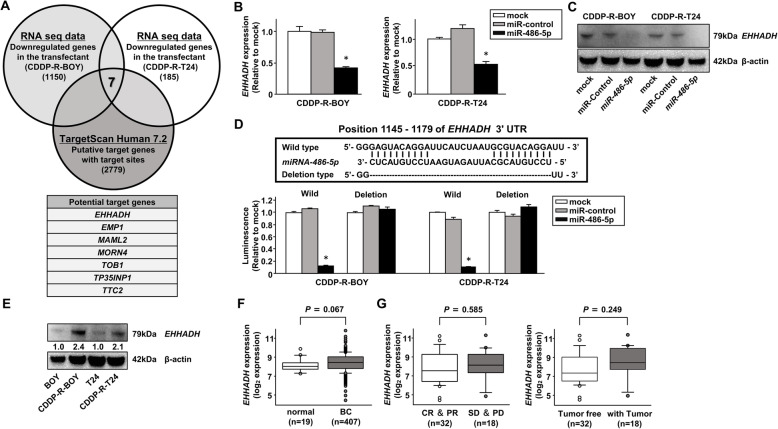

Identification of EHHADH mRNA as a target regulated by miR-486-5p in CDDP-R-BC cell lines

Next, we sought further insights into the molecular mechanisms regulated by tumor suppressive miRNA-486-5p. Thus, we used a combination of in silico analyses and RNA sequencing analyses to search for genes in CDDP-R BC cells that were targeted by miRNA-486-5p. TargetScan database Release 7.1 (http://www.targetscan.org) identified 2779 possible mRNAs as candidate targets of miRNA-486-5p. Next, we narrowed the number of genes based upon the expression profiles of mRNAs of CDDP-R BC cell lines before and after transfection with miRNA-486-5p. Finally, we selected 7 candidate target genes (EHHADH, EMP1, MAML2, MORN4, TOB1, TP35INP1, TTC2) (Fig. 5a). Among them, only EHHADH gene expression was downregulated at both the mRNA and the protein expression level in miRNA-486-5p-transfected cells (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Figure 5b).

Fig. 5.

Identification of EHHADH mRNA as a target regulated by miR-486-5p in CDDP-R-BC cell lines. a A Venn diagram of mRNA sequences and in silico analyses indicated that 7 putative candidate target genes of miRNA-486-5p were key molecules in cisplatin-resistant BCs. b The EHHADH mRNA expression levels determined by qRT-PCR and (c) its protein levels determined by Western blot in miR-486-5p transfectants compared with mock or miR-control transfectants. *, P < 0.001. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 8. d Dual-luciferase reporter assays using vectors encoding putative miRNA target sites for WT or deleted regions. Luminescence intensity was significantly reduced by co-transfection with miR-486-5p and the vector carrying the WT 3′-UTR. *, P < 0.001. e The protein levels of EHHADH in CDDP-R BC and parental BC cells. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 8. f EHHADH mRNA expression in the BLCA cohort in TCGA, EHHADH expression in BLCA samples compared with those in normal samples. g EHHADH expression in cisplatin-sensitive (CR and PR) and cisplatin-resistant (SD and PD) groups treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. EHHADH expression in patients with or without tumor

To determine whether EHHADH was directly regulated by miRNA-486-5p, we performed dual-luciferase reporter assays in CDDP-R BC cell lines. The TargetScan database predicted that there were 2 binding sites for miRNA-486-5p. We used vectors encoding the partial WT sequence of the 3′-UTR of EHHADA, including the predicted miRNA-486-5p target sites. The luminescence intensity was significantly reduced by co-transfection with miRNA-486-5p and the vector carrying the WT 3′-UTR, whereas it was not reduced by transfection with the deletion vector from which the binding site had been removed (Fig. 5d). These data suggested that miRNA-486-5p was directly bound to each specific position in the 3′-UTR of EHHADH mRNA.

Expression levels of EHHADH correlated with cisplatin resistance in BC in TCGA cohorts and in vitro

We examined the correlation of EHHADH expression levels with cisplatin sensitivities and clinical categories. We confirmed that the protein level of EHHADH was increased in CDDP-R BC cell lines compared with parental cell lines (Fig. 5e). Among the BLCA cohort in TCGA, we found that gene expression of EHHADH was somewhat higher in bladder cancer specimens compared with adjacent noncancerous tissues (P = 0.067; Fig. 5f). However, there were no significant differences in the expression levels of EHHADH among clinicopathological parameters (Supplementary Figure 5c). Thus, we examined patients who were treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The cohort was divided into two groups: (1) a cohort that included CR (Complete Response) and PR (Partial Response) patients that showed tumor suppression due to cisplatin-based chemotherapy and (2) a cohort that included SD (Stable Disease) and PD (Progressive Disease) patients who did not show tumor suppression due to cisplatin resistance [26]. Even though we could not find a significant difference between in the CR and PR group and in the SD and PD group, the expression level of EHHADH in the SD and PD group tended to be a little higher than that in the CR and PR group (Fig. 5g), which was different from the data showing no difference in the expression levels of EHHADH among clinicopathological parameters in Supplementary Figure 5C. When we separated the cohort into a tumor-free group and a residual tumor group, there was also a tendency that the expression of EHHADH was higher in the tumor-free group than in the tumor-free group.

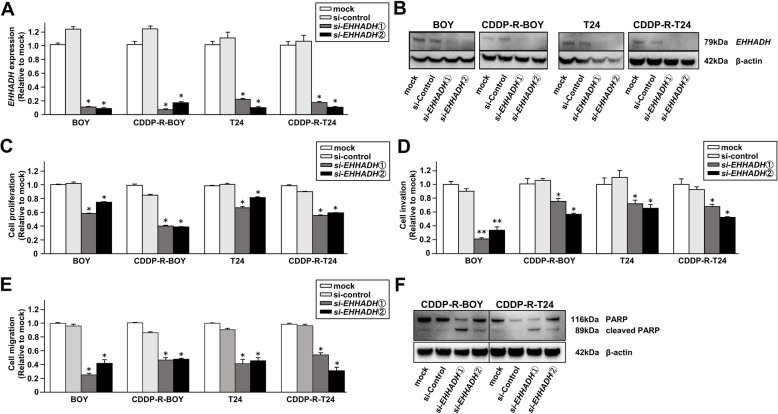

Effects of EHHADH knockdown on cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in CDDP-R BC cells

We carried out loss-of-function assays by using si-EHHADH transfections to investigate the functional role of EHHADH in CDDP-R-BC cells. We employed 2 different si-EHHADH molecules that effectively downregulated EHHADH mRNA and protein expression in both cell lines (Fig. 6a, b). Transfections of si-EHHADH did not regulate miRNA-486-5p expression (Supplementary Figure 6a). XTT assays demonstrated that cell proliferation was significantly inhibited in both parental and CDDP-R cells transfected with si-EHHADH in comparison with mock or si-control transfected cells. Moreover, Matrigel invasion assays and wound healing assays showed that cell invasion and migration activities were significantly inhibited in these si-EHHADH transfectants compared to their counterparts (Fig. 6c, d, e, Supplementary Figure 6b, c). The apoptotic cell numbers were significantly greater in si-EHHADH transfectants than in their counterparts. Western blots showed that cleaved PARP expression was markedly increased in si-EHHADH transfectants.

Fig. 6.

Effects of EHHADH knockdown on cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in CDDP-R BC cells. a EHHADH mRNA expression [measured by RT-qPCR] and (b) EHHADH protein levels [measured by Western blot analyses] were assessed to validate the knockdown efficiency of si-EHHADH. *, P < 0.001. c Cell proliferation determined by XTT assay. *, P < 0.001. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 8. d Cell invasion activity determined with the Matrigel invasion assay. *, P < 0.001. e Cell migration activity determined with wound healing assays. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01. All experiments were performed in quadruplicate and si-EHHADH transfectants were compared with mock or si-control transfectants. f Western blot analysis of apoptotic markers (cleaved PARP and PARP) in CDDP-R-BOY and CDDP-R-T24. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 8.

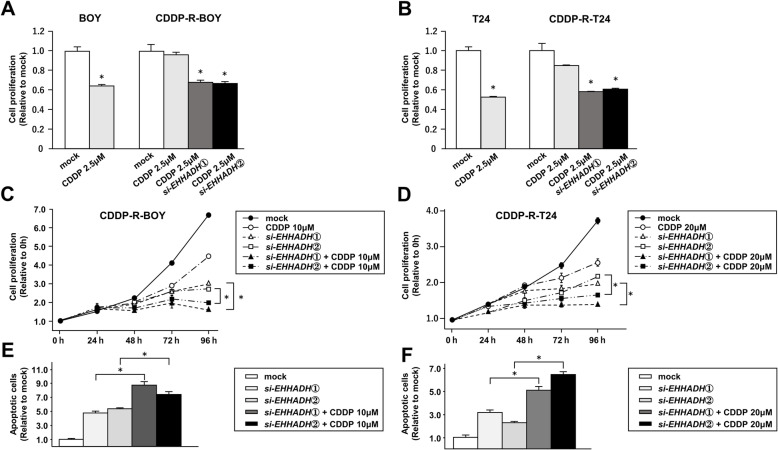

Knockdown of EHHADH improves sensitivity to CDDP in CDDP-R-BC cell lines

We also investigated whether knockdown of EHHADH improved the sensitivity to cisplatin in CDDP-R-BC cells. The cell proliferation of CDDP-R-BOY was not suppressed at 2 μM cisplatin, however a combination of si-EHHADH-transfection and cisplatin clearly had an additive effect and significantly suppressed cell proliferation at 2 μM cisplatin (Fig. 7a). Similar results were observed in CDDP-R-T24 with 10 μM of cisplatin (Fig. 7b). Next, we observed the proliferative activity after combining cisplatin and si-EHHADH transfection in a time series and found that the combination treatment clearly inhibited cell proliferation compared to the individual treatments (Fig. 7c, d). Further, the number of apoptotic cells (apoptotic and early apoptotic cells) was significantly higher in the combination treatment (Fig. 7e, f, Supplementary Figure 7a). These results suggested that EHHADH was involved in cisplatin resistance in BC and that its inhibition might improve the cells’ sensitivity to cisplatin.

Fig. 7.

Transfection of si-EHHADH increased sensitivity to CDDP in CDDP-R-BC cell lines. The IC50 concentration of cisplatin was given to parental BC cells. Transfection of 10 nM si-EHHADH increased the cisplatin sensitivity in (a) CDDP-R-BOY and (b) CDDP-R-T24 cells as determined by XTT assay. *, P < 0.001. The combination of si-EHHADH transfection and cisplatin administration to (c) CDDP-R-BOY and (d) CDDP-R-T24 cells clearly had an additive effect and significantly suppressed cell proliferation. *, P < 0.001. e, f Apoptosis assays were carried out using flow cytometric analysis of CDDP-R-BC cells. *, P < 0.001

Discussion

EHHADH is 1 of the 4 enzymes of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway [27]. Beta-oxidation of fatty acids occurs in both mitochondria and peroxisomes. The preponderance of activity is found in mitochondria where fatty acid molecules are disassembled to acetyl-CoA, which is oxidized to CO2 in the citric acid cycle to produce energy [27, 28]. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation is involved in the decomposition of very long chain fatty acids, bile acid synthesis and myelin sheath lipid synthesis [29, 30]. Recently, peroxisomes have gained attention in human health with potential impact on a large number of diseases such as neurodegeneration, age-related disorders, and cancer [31]. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are involved in the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway and are believed to affect cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, neurological and psychiatric disorders and malignancies [32].

In cancer cells, abnormal expression of microRNAs can disturb normally operating RNA networks and disrupt physiologic processes [11]. microRNAs are important regulators that control cancer progression pathways, including cell proliferation, differentiation, development, apoptosis and drug resistance [33, 34]. Our past studies demonstrated that specific miRNAs are abnormally expressed and impact cancer progression through their targeting of several oncogenic genes and pathways [35–37]. Other researchers have reported that some microRNAs are involved in cisplatin resistance in BC. Liu et al. showed that miRNA-214 could reduce cisplatin resistance by targeting netrin-1 [38]. Li et al. demonstrated that decreased expression of miRNA-218 could contribute to resistance to cisplatin by suppressing glucose metabolism [39]. Herein, we focused on miRNA-486-5p, a transcript that was downregulated in CDDP-R BC cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24) compared with parental BC cell lines (BOY, T24). The molecular mechanism by which miRNA-486-5p is downregulated in BC remains unclear. However, miRNA-486-5p is located on chromosome 8p11, and loss of material from chromosome arm 8p was a frequent cytogenetic alteration in uroepithelial carcinoma [40]. It was reported that miRNA-486-5p was a tumor suppressor miRNA in many cancer types such as non-small cell lung, breast, colon and hepatocellular carcinoma [41–44]. As a tumor suppressor gene, miRNA-486-5p overexpression inhibited cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and induced apoptosis in BC and CDDP-R BC cell lines. Also, miRNA-486-5p was reportedly involved in sensitivity to cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer. Xiaoyan et al. reported that miRNA-486-5p inhibits EMT by targeting TWF1 and improves sensitivity to cisplatin [45]. Similarly, we revealed that miRNA-486-5p overcomes cisplatin resistance and the additive effect on cell growth suppression. Recently, Salimian et al. showed that miRNA-486-5p had anti-tumor effects and improved CDDP sensitivity through induction of apoptosis in muscle-invasive BC [46]. Therefore, Our finding adds a new perspective to their reports, we demonstrated that EHHADH was a directly targeted by miR-486-5p. This finding had not been reported previously. According to TargetScan database Release 7.1, it is possible that among the 28 microRNAs that are downregulated in cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24), 5 microRNAs (miR-486-5p, miR-6768-5p, miR-548ar-3p, miR-6816-3p, miR-4731-3p) regulate the expression of EHHADH. Even though we focused on miR-486-5p in this study, it is possible that the other microRNAs are involved in cisplatin resistance by regulating EHHADH. Further study is necessary to elucidate the mechanism by which EHHADH contributes to cisplatin resistance through regulation by microRNA in BC.

In this study, we confirmed that the level of EHHADH protein was elevated in CDDP-R BC cell lines compared with parental cell lines, and that loss of EHHADH gene function significantly inhibited cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion and increased the cells’ sensitivity to cisplatin. However, we could not find a significant correlation between EHHADH expression levels and cisplatin-based chemotherapy response in TCGA database. This could be due to the limited number of samples in TCGA database. Also, mRNA expression does not always match protein expression. Furthermore, when cisplatin-based chemotherapy is used, cisplatin is combined with other anticancer agents. Because our analysis showed a tendency for upregulation of EHHADH expression in patients with cisplatin resistance in spite of the small sample size and bias, the results suggest that EHHADH could be a new molecular target and marker for progressive BC.

The mechanisms by which cells gain resistance to cisplatin are very complex. Thus, Galluzzi et al. classified the mechanisms of resistance into 4 categories [47]. The first category is pre-target resistance in which the binding of cisplatin to DNA is reduced, perhaps because of lowered cisplatin uptake into cells. The second category is on-target resistance due to inadequate direct binding between DNA and cisplatin. The third category is post-target resistance in which cisplatin-mediated DNA damage is ineffective. The last category is off-target resistance in which no signaling pathway is triggered by cisplatin. For example, the upregulation of excision repair cross complementing 1 (ERCC1), a DNA repair gene [48], could repair DNA damage caused by addition of cisplatin [49]. This cisplatin resistance mechanism is classified as on-target resistance [47]. In another example, TP53 mutant patients are often cisplatin-resistant in ovarian cancer [50]. Because TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene that mainly induces apoptosis [51], patients with a faulty TP53 gene cannot proceed to cellular apoptosis (post-target resistance) [47]. Regarding EHHADH, it appears to contribute to pre-target resistance for the following reasons. First, Evelien et al. reported that increased fatty acid synthesis reduces intracellular unsaturated fatty acid production. Unsaturated fatty acids are a source of reactive free radicals, and reduction of reactive free radicals is involved in cisplatin resistance [52]. Second, Chiranjeevi et al. demonstrated that fatty acid synthesis may permit plasma membrane remodeling by varying the fatty acid and lipid composition [53, 54]. This variation could lead to altered drug uptake and intracellular drug concentration, affecting drug resistance. Because it remains unclear how the functions of EHHADH cause cisplatin resistance, further studies are necessary to elucidate the associations between the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway in which EHHADH is involved and cisplatin resistance.

Conclusions

We identified EHHADH as a novel target of miRNA-486-5p in cisplatin-resistant BCs. The expression of EHHADH was decreased in cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that EHHADH is involved in cisplatin resistance. The discovery of molecular targets mediated by tumour-suppressive microRNAs may lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in BC and the development of new therapeutic strategies to treat progressive BC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 : Supplementary Figure 1. (a) Cell proliferation determined by XTT assay compared with parental BC cell lines and CDDP-R BC cell lines. *, P < 0.001. (b) Heatmap of miRNA-seq comparing parental and CDDP-R cell lines (BOY vs CDDP-R-BOY, T24 vs CDDP-R-T24).

Additional file 2 : Supplementary Figure 2. (a) Among the BLCA cohort of TCGA, expression levels of candidate miRNAs (miRNA-624-3p, miRNA-424-5p, miRNA-545-5p, miR-628-3p). We determined correlations among expression levels and pathological T categories and clinical stages. (b) Kaplan-Meier analysis using TCGA dataset revealed that the high miRNA-545-5p expression group did not have significantly lower OS than the low miRNA-486-5p expression group (P = 0.162).

Additional file 3 : Supplementary Figure 3. (a) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in miR-486-5p transfectants compared with mock or miR-control transfectants by qRT-PCR. (b) Pictures of cell invasion assays. (c) Pictures of cell migration assays.

Additional file 4 : Supplementary Figure 4. (a) Apoptosis assays indicated that the number of apoptotic cells was significantly greater in the combination of miRNA-486-5p-transfection and cisplatin than single treatment in flow cytometry, *P < 0.0001.

Additional file 5 : Supplementary Figure 5. (a) Heatmap of mRNA-seq comparing mock with miRNA-486-5p transfection in CDDP-R cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24). (b) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in miR-486-5p transfectants compared with mock or miR-control transfectants by qRT-PCR. (c) Among the BLCA cohort of TCGA, there were no significant differences in expression levels of EHHADH in pathological categories or clinical stages.

Additional file 6 : Supplementary Figure 6. (a) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in si-EHHADH transfectants compared with mock or si-control transfectants determined by qRT-PCR. (b, c) Pictures of cell invasion assays and cell migration assays in si-EHHADH transfectants compared with mock or si-control transfectants.

Additional file 7 : Supplementary Figure 7. (a) Apoptosis assays indicated that the number of apoptotic cells was significantly greater in the combination of si-EHHADH-transfection and cisplatin than single treatment in flow cytometry, *P < 0.0001. (b) Correlations of the expression of miRNA-545-5p and EHHADH in bladder cancer samples in TCGA database.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Keiko Yoshitomi, Department of Urology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University (Kagoshima, Japan), for excellent laboratory assistance.

Abbreviations

- EHHADH

Enoyl-CoA, hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase

- BC

Bladder cancer

- microRNA

Microribonucleic acid

- CDDP-R

Cisplatin-resistant

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- NMIBC

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- MIBC

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- OS

Overall survival rate

- CTR1

Copper transporter1

- EMT

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

- PTEN

Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog deleted on Chromosome 10

- AKT

RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase

- BCL2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- BLCA

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- UTR

Untranslated Region

- ERCC1

Excision repair cross complementing 1

- TP53

Tumor protein p53

Authors’ contributions

SO designed the study, analyzed data, and finalized the manuscript; KK, MT, YO, TS, and ST performed experiments and collected and analyzed data; HY, MY, YY, MN, and HE secured research funding and drafted the article. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript and reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding

The role of funders in this study were as follows: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI) 18 K09198, to Yasutoshi Yamada; 19 K09715 to Masayuki Nakagawa; 19 K18615 to Masaya Yonemori; 20 K18146 to Yoichi Osako; and Takeda Science Foundation in Japan to Hirofumi Yoshino.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal studies were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee at Kagoshima University (MD18094), and carried out under animal license guidelines of the Kagoshima University Animal Care Committee. Because the clinical data from patients were derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the need for ethics approval or written informed consent is deemed unnecessary as elsewhere in published papers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shunsuke Okamura, Email: shunce0807@gmail.com.

Hirofumi Yoshino, Email: uroyoshi2002@yahoo.co.jp.

Kazuki Kuroshima, Email: k.black.black.gum@gmail.com.

Masafumi Tsuruda, Email: tu.tu.tu.tsuruta@gmail.com.

Yoichi Osako, Email: minority.y.o@gmail.com.

Takashi Sakaguchi, Email: sg-t.06141014@outlook.jp.

Shuichi Tatarano, Email: taracho@m3.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Masayuki Nakagawa, Email: nakagawa@m.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Hideki Enokida, Email: henokida@m2.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-020-07717-0.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Systemic chemotherapy in locally advanced and/or metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(6):456–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanee S, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Murugan P, Kumar R, Nepple KG, Paner GP, Patel MI, Raspollini MR, Lopez-Beltran A, Konety BR. Update of the international consultation on urological diseases on bladder cancer 2018: non-urothelial cancers of the urinary bladder. World J Urol. 2019;37(1):107–114. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia JA, Dreicer R. Systemic chemotherapy for advanced bladder cancer: update and controversies. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(35):5545–5551. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.08.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riddell IA. Cisplatin and Oxaliplatin: Our Current Understanding of Their Actions. Met Ions Life Sci. 2018;18:1–42. 10.1515/9783110470734-007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shen DW, Pouliot LM, Hall MD, Gottesman MM. Cisplatin resistance: a cellular self-defense mechanism resulting from multiple epigenetic and genetic changes. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(3):706–721. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida S, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Herskowitz I. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(22):14298–14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang F, Ren C, Wang J, Wang S, Yang L, Han X, Chen Y, Tong G, Yang G. The crosstalk between STAT3 and p53/RAS signaling controls cancer cell metastasis and cisplatin resistance via the slug/MAPK/PI3K/AKT-mediated regulation of EMT and autophagy. Oncogenesis. 2019;8(10):59. doi: 10.1038/s41389-019-0165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo J, Yao JF, Deng XF, Zheng XD, Jia M, Wang YQ, Huang Y, Zhu JH. 14, 15-EET induces breast cancer cell EMT and cisplatin resistance by up-regulating integrin αvβ3 and activating FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drayton RM. The role of microRNA in the response to cisplatin treatment. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40(4):821–825. doi: 10.1042/bst20120055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, Liu Z, Ding Z, Hou S, Li J, Jiang K. MicroRNA-155 increases colon cancer chemoresistance to cisplatin by targeting forkhead box O3. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(4):4781–4788. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Kong W, He L, Zhao JJ, O'Donnell JD, Wang J, Wenham RM, Coppola D, Kruk PA, Nicosia SV, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling in human ovarian cancer: miR-214 induces cell survival and cisplatin resistance by targeting PTEN. Cancer Res. 2008;68(2):425–433. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-07-2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu W, Shan X, Wang T, Shu Y, Liu P. miR-181b modulates multidrug resistance by targeting BCL2 in human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(11):2520–2529. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, Balmain A, Bruder G, Chaplin DJ, Double JA, Everitt J, Farningham DAH, Glennie MJ, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(11):1555–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz EJ, Diefenbacher ME, Nelson JK, Sancho R, Pucci F, Chakraborty A, Moreno P, Annibaldi A, Liccardi G, Encheva V, et al. LUBAC determines chemotherapy resistance in squamous cell lung cancer. J Exp Med. 2019;216(2):450–465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichimi T, Enokida H, Okuno Y, Kunimoto R, Chiyomaru T, Kawamoto K, Kawahara K, Toki K, Kawakami K, Nishiyama K, et al. Identification of novel microRNA targets based on microRNA signatures in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(2):345–352. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hidaka H, Seki N, Yoshino H, Yamasaki T, Yamada Y, Nohata N, Fuse M, Nakagawa M, Enokida H. Tumor suppressive microRNA-1285 regulates novel molecular targets: aberrant expression and functional significance in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3(1):44–57. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada Y, Hidaka H, Seki N, Yoshino H, Yamasaki T, Itesako T, Nakagawa M, Enokida H. Tumor-suppressive microRNA-135a inhibits cancer cell proliferation by targeting the c-MYC oncogene in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(3):304–312. doi: 10.1111/cas.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SH, Ho JN, Jin H, Lee SC, Lee SE, Hong SK, Lee JW, Lee ES, Byun SS. Upregulated expression of BCL2, MCM7, and CCNE1 indicate cisplatin-resistance in the set of two human bladder cancer cell lines: T24 cisplatin sensitive and T24R2 cisplatin resistant bladder cancer cell lines. Investig Clin Urol. 2016;57(1):63–72. doi: 10.4111/icu.2016.57.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byun SS, Kim SW, Choi H, Lee C, Lee E. Augmentation of cisplatin sensitivity in cisplatin-resistant human bladder cancer cells by modulating glutathione concentrations and glutathione-related enzyme activities. BJU Int. 2005;95(7):1086–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itesako T, Seki N, Yoshino H, Chiyomaru T, Yamasaki T, Hidaka H, Yonezawa T, Nohata N, Kinoshita T, Nakagawa M, et al. The microRNA expression signature of bladder cancer by deep sequencing: the functional significance of the miR-195/497 cluster. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e84311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe H, Okada M, Kaji Y, Satouchi M, Sato Y, Yamabe Y, Onaya H, Endo M, Sone M, Arai Y: [New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours-revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1)]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2009;36(13):2495–2501. [PubMed]

- 27.Klootwijk ED, Reichold M, Helip-Wooley A, Tolaymat A, Broeker C, Robinette SL, Reinders J, Peindl D, Renner K, Eberhart K, et al. Mistargeting of peroxisomal EHHADH and inherited renal Fanconi’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):129–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houten SM, Denis S, Argmann CA, Jia Y, Ferdinandusse S, Reddy JK, Wanders RJ. Peroxisomal L-bifunctional enzyme (Ehhadh) is essential for the production of medium-chain dicarboxylic acids. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(7):1296–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waterham HR, Ferdinandusse S, Wanders RJ. Human disorders of peroxisome metabolism and biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(5):922–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fransen M, Lismont C, Walton P. The Peroxisome-Mitochondria Connection: How and Why? Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1126. 10.3390/ijms18061126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Islinger M, Voelkl A, Fahimi HD, Schrader M. The peroxisome: an update on mysteries 2.0. Histochem Cell Biol. 2018;150(5):443–471. doi: 10.1007/s00418-018-1722-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirza AZ, Althagafi II, Shamshad H. Role of PPAR receptor in different diseases and their ligands: physiological importance and clinical implications. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;166:502–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshino H, Seki N, Itesako T, Chiyomaru T, Nakagawa M, Enokida H. Aberrant expression of microRNAs in bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10(7):396–404. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson KM, Weiss GJ. MicroRNAs and cancer: past, present, and potential future. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(12):3655–3660. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-08-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatarano S, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, Enokida H, Yoshino H, Hidaka H, Yamasaki T, Kawahara K, Nishiyama K, Seki N, et al. miR-218 on the genomic loss region of chromosome 4p15.31 functions as a tumor suppressor in bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2011;39(1):13–21. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugita S, Yoshino H, Yonemori M, Miyamoto K, Matsushita R, Sakaguchi T, Itesako T, Tatarano S, Nakagawa M, Enokida H. Tumorsuppressive microRNA223 targets WDR62 directly in bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2019;54(6):2222–2236. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshino H, Enokida H, Itesako T, Tatarano S, Kinoshita T, Fuse M, Kojima S, Nakagawa M, Seki N. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related microRNA-200s regulate molecular targets and pathways in renal cell carcinoma. J Hum Genet. 2013;58(8):508–516. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Bi J, Li Z, Li Z, Liu X, Kong C. miR-214 reduces cisplatin resistance by targeting netrin-1 in bladder cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41(3):1765–1773. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li P, Yang X, Cheng Y, Zhang X, Yang C, Deng X, Li P, Tao J, Yang H, Wei J, et al. MicroRNA-218 increases the sensitivity of bladder cancer to cisplatin by targeting Glut1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41(3):921–932. doi: 10.1159/000460505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fadl-Elmula I. Chromosomal changes in uroepithelial carcinomas. Cell Chromosome. 2005;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-9268-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian F, Wang J, Ouyang T, Lu N, Lu J, Shen Y, Bai Y, Xie X, Ge Q. MiR-486-5p serves as a good biomarker in nonsmall cell lung cancer and suppresses cell growth with the involvement of a target PIK3R1. Front Genet. 2019;10:688. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Mou Q, Li P, Yang Z, Wang Z, Niu J, Liu Y, Sun Z, Lv S, Zhang B, et al. MiR-486-5p inhibits IL-22-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cell by repressing Dock1. J Cancer. 2019;10(19):4695–4706. doi: 10.7150/jca.30596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Fu J, Zhang Z, Qin H. miR-486-5p regulates the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through targeting PIK3R1. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(5):7243–7248. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J, Xiao B, Li X, He Y, Li L, Sun Z. MiR-486-5p suppresses proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through downregulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CBL. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:2732057. doi: 10.1155/2019/2732057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin X, Pang W, Zhang Q, Huang H. MicroRNA-486-5p improves nonsmall-cell lung cancer chemotherapy sensitivity and inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting twinfilin actin binding protein 1. J Int Med Res. 2019. 10.1177/0300060519850739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Salimian J, Baradaran B, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Moridikia A, Ahmadi A. MiR-486-5p enhances cisplatin sensitivity of human muscle-invasive bladder cancer cells by induction of apoptosis and down-regulation of metastatic genes. Urol Oncol. 2020. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31(15):1869–1883. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manandhar M, Boulware KS, Wood RD. The ERCC1 and ERCC4 (XPF) genes and gene products. Gene. 2015;569(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bellmunt J, Paz-Ares L, Cuello M, Cecere FL, Albiol S, Guillem V, Gallardo E, Carles J, Mendez P, de la Cruz JJ, et al. Gene expression of ERCC1 as a novel prognostic marker in advanced bladder cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):522–528. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gadducci A, Cosio S, Muraca S, Genazzani AR. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and chemosensitivity to platinum and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer: biological data and clinical implications. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;23(5):390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aubrey BJ, Strasser A, Kelly GL. Tumor-Suppressor Functions of the TP53 Pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(5):a026062. 10.1101/cshperspect.a026062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Rysman E, Brusselmans K, Scheys K, Timmermans L, Derua R, Munck S, Van Veldhoven PP, Waltregny D, Daniëls VW, Machiels J, et al. De novo lipogenesis protects cancer cells from free radicals and chemotherapeutics by promoting membrane lipid saturation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):8117–8126. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peetla C, Vijayaraghavalu S, Labhasetwar V. Biophysics of cell membrane lipids in cancer drug resistance: implications for drug transport and drug delivery with nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(13–14):1686–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wen H, Lee S, Zhu WG, Lee OJ, Yun SJ, Kim J, Park S. Glucose-derived acetate and ACSS2 as key players in cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864(3):413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 : Supplementary Figure 1. (a) Cell proliferation determined by XTT assay compared with parental BC cell lines and CDDP-R BC cell lines. *, P < 0.001. (b) Heatmap of miRNA-seq comparing parental and CDDP-R cell lines (BOY vs CDDP-R-BOY, T24 vs CDDP-R-T24).

Additional file 2 : Supplementary Figure 2. (a) Among the BLCA cohort of TCGA, expression levels of candidate miRNAs (miRNA-624-3p, miRNA-424-5p, miRNA-545-5p, miR-628-3p). We determined correlations among expression levels and pathological T categories and clinical stages. (b) Kaplan-Meier analysis using TCGA dataset revealed that the high miRNA-545-5p expression group did not have significantly lower OS than the low miRNA-486-5p expression group (P = 0.162).

Additional file 3 : Supplementary Figure 3. (a) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in miR-486-5p transfectants compared with mock or miR-control transfectants by qRT-PCR. (b) Pictures of cell invasion assays. (c) Pictures of cell migration assays.

Additional file 4 : Supplementary Figure 4. (a) Apoptosis assays indicated that the number of apoptotic cells was significantly greater in the combination of miRNA-486-5p-transfection and cisplatin than single treatment in flow cytometry, *P < 0.0001.

Additional file 5 : Supplementary Figure 5. (a) Heatmap of mRNA-seq comparing mock with miRNA-486-5p transfection in CDDP-R cell lines (CDDP-R-BOY, CDDP-R-T24). (b) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in miR-486-5p transfectants compared with mock or miR-control transfectants by qRT-PCR. (c) Among the BLCA cohort of TCGA, there were no significant differences in expression levels of EHHADH in pathological categories or clinical stages.

Additional file 6 : Supplementary Figure 6. (a) Expression levels of miRNA-486-5p quantified in si-EHHADH transfectants compared with mock or si-control transfectants determined by qRT-PCR. (b, c) Pictures of cell invasion assays and cell migration assays in si-EHHADH transfectants compared with mock or si-control transfectants.

Additional file 7 : Supplementary Figure 7. (a) Apoptosis assays indicated that the number of apoptotic cells was significantly greater in the combination of si-EHHADH-transfection and cisplatin than single treatment in flow cytometry, *P < 0.0001. (b) Correlations of the expression of miRNA-545-5p and EHHADH in bladder cancer samples in TCGA database.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.