Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

This observational, cross-sectional study based aimed to test whether heart failure (HF)-disease management program (DMP) components are influencing care and clinical decision-making in Brazil.

METHODS:

The survey respondents were cardiologists recommended by experts in the field and invited to participate in the survey via printed form or email. The survey consisted of 29 questions addressing site demographics, public versus private infrastructure, HF baseline data of patients, clinical management of HF, performance indicators, and perceptions about HF treatment.

RESULTS:

Data were obtained from 98 centers (58% public and 42% private practice) distributed across Brazil. Public HF-DMPs compared to private HF-DMP were associated with a higher percentage of HF-DMP-dedicated services (79% vs 24%; OR: 12, 95% CI: 94-34), multidisciplinary HF (MHF)-DMP [84% vs 65%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 1-8), HF educational programs (49% vs 18%; OR: 4; 95% CI: 1-2), written instructions before hospital discharge (83% vs 76%; OR: 1; 95% CI: 0-5), rehabilitation (69% vs 39%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 1-9), monitoring (44% vs 29%; OR: 2; 95% CI: 1-5), guideline-directed medical therapy-HF use (94% vs 85%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 0-15), and less B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) dosage (73% vs 88%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 1-9), and key performance indicators (37% vs 60%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 1-7). In comparison to non- MHF-DMP, MHF-DMP was associated with more educational initiatives (42% vs 6%; OR: 12; 95% CI: 1-97), written instructions (83% vs 68%; OR: 2: 95% CI: 1-7), rehabilitation (69% vs 17%; OR: 11; 95% CI: 3-44), monitoring (47% vs 6%; OR: 14; 95% CI: 2-115), GDMT-HF (92% vs 83%; OR: 3; 95% CI: 0-15). In addition, there were less use of BNP as a biomarker (70% vs 84%; OR: 2; 95% CI: 1-8) and key performance indicators (35% vs 51%; OR: 2; 95% CI: 91,6) in the non-MHF group. Physicians considered changing or introducing new medications mostly when patients were hospitalized or when observing worsening disease and/or symptoms. Adherence to drug treatment and non-drug treatment factors were the greatest medical problems associated with HF treatment.

CONCLUSION:

HF-DMPs are highly heterogeneous. New strategies for HF care should consider the present study highlights and clinical decision-making processes to improve HF patient care.

Keywords: Heart Failure, Disease Management Program, Education Monitoring, Clinical Decision-Making, Multidisciplinary Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is the leading cause of hospital admission and readmissions in the United States among adults aged ≥65 years, creating a significant healthcare burden (1). Despite the undeniable progress in HF treatment over the past few years, the number of hospital readmissions and associated healthcare costs remain very high (2). The goals of the HF disease management programs (DMPs) or HF clinics, include optimization of drug therapy, intensive patient education, vigilant follow-up for early recognition of complications, and identification and management of patients’ comorbidities to reduce mortality rates, hospital admissions, and improve patients’ health-related quality of life (2-4).

HF-DMPs are associated with improved HF outcomes (5). However, the content and effectiveness of HF-DMP interventions may vary widely (6) since they contain several components that contribute to their success (7). However, in clinical practice, the association of each component with the effectiveness of the HF-DMP has not been studied and HF care models in low- and middle-income countries remain unknown. In addition, doctor perceptions about the decision-making process in HF management have not been previously reported. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate HF care models and HF-DMPs in a middle-income country using a questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey in a clinical setting.

METHODS

Survey design

The CLIMB-HF is an observational, cross-sectional, survey-based study administered to cardiologists from major cardiology centers across Brazil. The survey was created to gather information regarding HF-DMP and/or HF care models routinely used in clinical practice.

Eligibility

Participants were recommended by members of the Heart Failure Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology based on their expertise and active engagement in HF patient management. The participant selection also aimed to include a broad range of public and private cardiology practice settings. Public institutions were defined as centers in which the government was responsible for patient management and related costs. Private centers were defined by financial support from private insurance companies covering a pre-defined list of medical procedures or by the patient.

Heart failure care model questionnaire

After reviewing the literature on DMPs for HF patients and in HF clinics, a questionnaire was developed with the assistance of expert cardiologists from clinics with HF-DMPs (Supplementary Table S1). All the physicians were also members of the Department of Heart Failure from the Brazilian Society of Cardiology. Patient chart review was not performed for this study. The interviewed physicians provided answers based on their perceptions and conceptions. The questionnaire (either in physical form or electronic using the SurveyMonkey platform) was distributed by the Novartis team from June to October 2016 to selected cardiologists, both from public and private systems. The survey was sent as a printed questionnaire or by email in an electronic format. The answers were anonymous. For some questions, the participants were asked to submit responses in order of importance. The questionnaire consisted of 29 questions to collect demographic data regarding the participant’s work facility; the type of facility (private or public); HF patient characteristics according to the physicians’ perception; HF clinical management including practice during follow-up, educational programs for patients and caregivers, monitoring, and/or cardiac rehabilitation; and performance indicators (Appendix).

Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the status of HF care models implemented in cardiology centers in Brazil.

The secondary objectives were to report the characteristics of the HF care models including implementation of educational programs for patients and caregivers, monitoring and cardiac rehabilitation programs, multidisciplinary team components, clinical practice in the management of HF patients under HF care models, demographic data and structure of the participating centers, the profile of HF patients, utilization of performance indicators related to HF, and cardiologists’ perceptions regarding patient profiles and treatment standards.

We compared private and public setting characteristics (the type of infrastructure and function) of HF care defined by subspecialized HF treatment available in ambulatory care, subspecialized HF treatment available hospitalization, and multidisciplinary care.

Data analysis

The center identities were blinded during the data analysis. Categorical variables are reported as percentages and numbers. Continuous data are presented as mean±standard deviation if normally distributed, or as the median and interquartile range if non-normally distributed. Groups were defined according to health care setting (public versus private), availability of specialized service for HF, higher specialized HF service, and multidisciplinary care. Centers with higher specialization for HF care were defined as those with a multidisciplinary approach with at least a cardiologist, a nurse, a physiotherapist (or physical educator), and a nutritionist. Those with partial or without multidisciplinary teams were considered non-specialized. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables between groups, as appropriate. Variables obtained as estimate proportions were compared using a test on equality of proportions after estimating counts based on patients in follow-up for each variable. All analyses were two-tailed and conducted at the 5% significance level. The sample size was not pre-specified, but a good representation of the different regions of Brazil was sought.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was sent as a printed questionnaire to 121 cardiologists (50 replied) and to 184 cardiologists in an electronic format with a link for the same questionnaire in the SurveyMonkey platform (49 replied). The total number of completed questionnaires received was 99, and one questionnaire that did not specify the type of service (public or private) was excluded from the analysis. Among the 98 valid questionnaires, 57 (58%) came from private centers and 41 (42%) came from public centers.

Demographic and structure data from participating sites

Demographic and site characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In both private and public centers, the most common HF etiology was ischemia. The availability of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD)/cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), surgical treatment, multidisciplinary care, cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, nurses, nutritionists, physiotherapists, psychologists, pharmacists, and physical trainers was reported. Results showed important differences between public and private center characteristics. In the public centers, the number of patients was higher with greater presentation of severe cases according to New York Heart Association functional class. Ischemic/hypertensive/valvular etiologies were more frequent in patients treated in the private setting, while patients treated in public centers more often presented with chagasic and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The percent of possible available treatments, presence of multidisciplinary care, and its components were higher in the public care system.

Table 1. Demographic and Structure Data from Participating Sites Comparing Public versus Private.

| Total n=99* | Public n=41 | Private n=57 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients under follow-up | 200 [100-600] | 500 [200-950] | 180 [50-130] | <0.001 |

| Patients attended per week | 16 [7-40] | 40 [16-60] | 10 [2-20] | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class (%) | ||||

| I | 18% | 14% | 28% | <0.001 |

| II | 36% | 34% | 43% | <0.001 |

| III | 29% | 32% | 20% | <0.001 |

| IV | 17% | 20% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Etiology (%) | ||||

| Ischemic | 29% | 28% | 32% | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive | 18% | 16% | 22% | <0.001 |

| Valvular | 10% | 7% | 16% | <0.001 |

| Chagasic | 15% | 18% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Cardiotoxicity | 2% | 2% | 2% | ns |

| Peripartum | 3% | 3% | 3% | ns |

| Idiopathic | 17% | 21% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Others | 6% | 5% | 7% | 0.06 |

| Number of hospitalizations due to HF per month | 10 [4-20] | 20 [10-25] | 10 [2-15] | 0.001 |

| Outpatient care type | ||||

| General care | 10% (9/90) | 5% (2/38) | 12% (5/51) | <0.001 |

| Cardiology care | 55% (39/90) | 16% (6/38) | 65% (33/51) | |

| Outpatient HF care | 18% (16/90) | 21% (8/38) | 16% (8/51) | |

| Outpatient and inpatient HF care | 29% (26/90) | 58% (22/38) | 8% (4/51) | |

| Available treatments | ||||

| ICD and CRT | 72% (63/87) | 87% (33/38) | 65% (30/49) | 0.008 |

| Surgical | 77% (67/87) (67 out of 87) | 95% (36/38) (36 out of 38) | 63% (31/49) (31 out of 49) | 0.001 |

| Heart transplant | 31% (27/87) | 45% (17/38) | 20% (10/49) | 0.015 |

| Circulatory support | 76% (39/87) | 58% (22/38) | 35% (17/49) | 0.031 |

| Multidisciplinary care | 74% (64/87) | 84% (31/37) | 65% (22/49) | 0.055 |

| Multidisciplinary components | ||||

| Cardiologists | 94% (59/63) | 100% (31/31) | 88% (28/32) | 0.060 |

| Cardiac Surgeon | 76% (51/63) | 94% (29/31) | 59% (19/32) | 0.002 |

| Nephrologists | 56% (35/63) | 66% (21/31) | 44% (14/32) | 0.055 |

| Nurses | 86% (55/63) | 100% (31/31) | 75% (24/32) | 0.005 |

| Nutritionists | 80% (51/63) | 87% (27/31) | 75% (24/32) | ns |

| Physiotherapists | 70% (45/63) | 81% (25/31) | 63% (20/32) | ns |

| Psychologists | 67% (43/63) | 87% (27/31) | 50% (16/16) | 0.002 |

| Social workers | 62% (40/63) | 88% (28/31) | 38% (12/32) | <0.001 |

| Pharmacists | 53% (34/64) | 61% (19/31) | 47% (15/47) | ns |

| Physical trainer | 50% (32/64) | 55% (17/31) | 47% (15/47) | ns |

| Others | 53% (34/64) | 7% (2/31) | 9% (3/32) | ns |

| Number of multidisciplinary components by center | 8 [6-10] | 9 [7-10] | 7 [4-10] | 0.011 |

IQR, interquartile range; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillators; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Multidisciplinary centers have at least two multidisciplinary members of the following professions: cardiology, nursing, physiotherapy and/or physical educator or nutritionist.

one center did not state type of center; p-value for public versus private.

Delivered care for heart failure patients in participating centers

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is available in most centers and is used especially for diagnosis and prognosis. Educational programs were generally underused, except in the public care system. Nonetheless, written instructions at hospital discharge were frequently used and performed by doctors and/or nurses in both settings. The participation rates in monitoring programs were low in both systems (public and private) but were higher in the public setting. The regular use of guidelines was very high in both public and private care systems, and the Brazilian Guidelines were the most utilized. However, other international guidelines were also used. Quality of life questionnaires were not conducted in most centers. Rehabilitation programs were more frequently available in the public care system. Key performance indicators were mainly used by private care centers. During hospitalization, medical decisions were mostly made by the hospital’s cardiology team or intensive care unit physicians. In private care, the outpatient unit cardiologists were responsible for the majority of HF treatment initiation, while in public care, this was performed by both the hospital cardiology team and outpatient facilities. There was no difference in the use of standard guideline-oriented therapy for HF, except for lower use of digoxin in private care. In public settings, compliance with the target dose of medications according to guidelines was higher.

When comparing the characteristics of care according to the presence or absence of a multidisciplinary team, there was a higher rate of BNP or NT-proBNP use to support treatment decisions, increased rates of educational, monitoring and rehabilitation programs, and a higher proportion of patients on target doses of medications according to guidelines (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Conversely, in centers without multidisciplinary care, medical decisions were performed more frequently by the hospital cardiology team. In centers with HF subspecialized care, there was a higher percentage of patient monitoring programs mainly in outpatient units, in addition to the use of non-doctor-specialized monitoring methods, digoxin, and a higher proportion of patients on target doses of medications according to the guidelines (Supplementary Table S3). In centers with highly specialized multidisciplinary care, the results also showed a greater percentage of patient monitoring programs at outpatient clinics using non-doctor specialized monitoring programs, more cardiac rehabilitation, higher use of digoxin/vasodilators, and patients under the target dose of medication according to guidelines (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 2. Delivered Care for Heart Failure Patients Comparing Public versus Private.

| Total | Public | Private | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP dosage available | 81% (64/79) | 73% (27/37) | 88% (37/42) | 0.087 |

| Indication for BNP | ||||

| Help in the diagnosis | 72% (46/64) | 67% (18/27) | 75% (28/37) | ns |

| Determine the prognosis | 61% (39/64) | 63% (17/27) | 60% (22/37) | ns |

| Help the treatment | 33% (6/27) | 22% (6/27) | 41% (15/37) | ns |

| Monitoring | 58% (37/64) | 48% (13/27) | 65% (24/37) | ns |

| Centers without BNP | ||||

| Lack of access | 80% (13/15) | 80% (8/10) | 100% (5/5) | ns |

| Considered not essential | 20% (3/15) | 30% (3/10) | 0% (0/5) | ns |

| Education program for patient | 33% (24/73) | 55% (17/31) | 22% (7/32) | 0.006 |

| Education program for caregivers | 24% (18/74) | 39% (12/31) | 19% (6/32) | 0.058 |

| Written instructions at hospital discharge | 84% (63/75) | 83% (29/35) | 76% (29/38) | ns |

| By Doctor | 66% (38/58) | 62% (18/29) | 69% (20/29) | ns |

| By Nurse | 33% (19/58) | 38% (11/29) | 28% (8/29) | |

| By Others | 1% (1/58) (1 out of 58) | 0% (0/29) (0 out of 29) | 3% (1/29) (1 out of 29) | |

| Patient monitoring programs | 39% (27/70) | 47% (17/36) | 29% (10/34) | ns |

| Using monitoring program | ||||

| At ambulatory using non-doctorspecialized monitoring | 20% (14/70) | 31% (11/36) | 9% (3/34) | 0.035 |

| At distance using phone or other methods | 14% (10/70) | 14% (5/36) | 15% (5/34) | ns |

| Regular use of HF guidelines | 90% (65/72) | 94% (34/36) | 86% (31/36) | ns |

| DEIC-BSC | 43% (31/72) | 50% (18/36) | 36% (13/36) | ns |

| ESC | 21% (15/72) | 19% (7/36) | 22% (8/36) | |

| AHA/ACC | 17% (12/72) | 14% (5/36) | 16% (7/36) | |

| Institution’s own protocol | 8% (6/72) | 8% (3/36) | 8% (3/36) | |

| Other guidelines | 1% (2/72) | 3% (1/36) | 0% (0/36) | |

| Not following guidelines | 10% (7/72) | 6% (2/36) | 14% (2/36) | |

| Using quality of life questionnaire | 26% (18/69) | 23% (8/35) | 29% (10/34) | ns |

| KCCQ | 3% (2/69) | 3% (1/35) | 3% (1/34) | ns |

| MLHFQ | 20% (14/69) | 17% (6/35) | 24% (8/34) | ns |

| Other | 3% (2/69) | 3% (1/35) | 3% (1/34) | ns |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 54% (37/68) | 69% (24/35) | 39% (13/33) | 0.016 |

| Key performance indicators | 53% (34/64) | 39% (13/33) | 68% (21/31) | 0.023 |

| Hospital mortality | 31% (20/64) | 22% (7/33) | 42% (13/31) | 0.074 |

| 6-month mortality | 20% (13/64) | 18% (6/33) | 23% (7/31) | ns |

| 30-day hospitalization after discharge | 33% (21/64) | 24% (8/33) | 42% (13/31) | ns |

| 90-day hospitalization after discharge | 14% (9/64) | 12% (4/33) | 16% (5/31) | ns |

| Hospitalization duration | 25% (6/64) | 24% (8/33) | 26% (8/31) | ns |

| Other | 3% (2/64) | 3% (1/33) | 3% (1/31) | ns |

| Medical decision in hospitalized patient in decompensated HF | ||||

| By hospital cardiology team | 44% | 48% | 38% | < 0.001 |

| By cardiologist who cares for the patient in the outpatient clinic | 43% | 41% | 46% | < 0.001 |

| By intensive care unit doctors if admitted in intensive care unit | 13% | 11% | 16% | < 0.001 |

| Beginning of HF treatment | ||||

| Cardiologist in hospital | 38% | 45% | 27% | < 0.001 |

| Cardiologist in ambulatory | 43% | 30% | 62% | < 0.001 |

| General practitioner | 11% | 15% | 4% | < 0.001 |

| Intensive care doctor | 4% | 3% | 5% | 0.102 |

| Geriatrics | 2% | 3% | 0.4% | 0.276 |

| Others | 3% | 4% | 2% | 0.147 |

| Prescribed HF treatment | ||||

| ACE-I | 97% (72/74) | 92% (33/36) | 100% (38/38) | ns |

| ARBs | 84% (62/74) | 81% (29/36) | 87% (33/38) | ns |

| β-blocker | 92% (68/74) | 92% (32/36) | 95% (36/38) | ns |

| Spironolactone | 93% (69/74) | 92% (32/36) | 97% (37/38) | ns |

| Digoxin | 39% (29/74) | 50% (18/36) | 29% (11/38) | 0.064 |

| Diuretics | 88% (65/74) | 86% (31/36) | 90% (34-38) | ns |

| Vasodilators | 51% (38/74) | 58% (21/36) | 45% (17/38) | ns |

| Patients with target doses of medication according guidelines (%) | 73% | 77% | 63% | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; Specialized HF care considered (in-hospital or outpatient);HF, heart failure; HF-DMP, disease management program for HF; Centers with at least one multidisciplinary member , centers having at least one of the following professions: cardiology, nursing, physiotherapy and/or physical educator or nutritionist; HF, heart failure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DEIC, Heart Failure Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; MDP, multidisciplinary program; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire; ACE-I Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; p, public versus private.

Evaluation of medical expectations, treatment objectives, and challenges in HF management

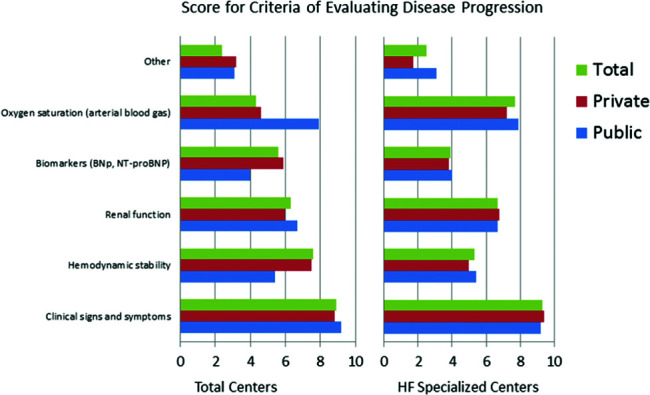

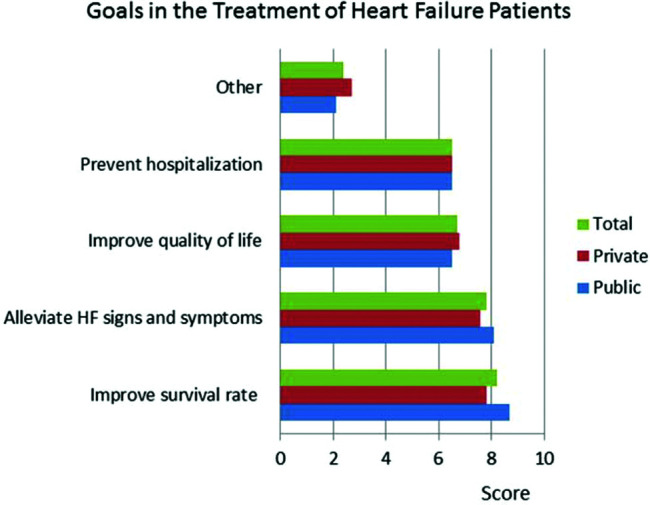

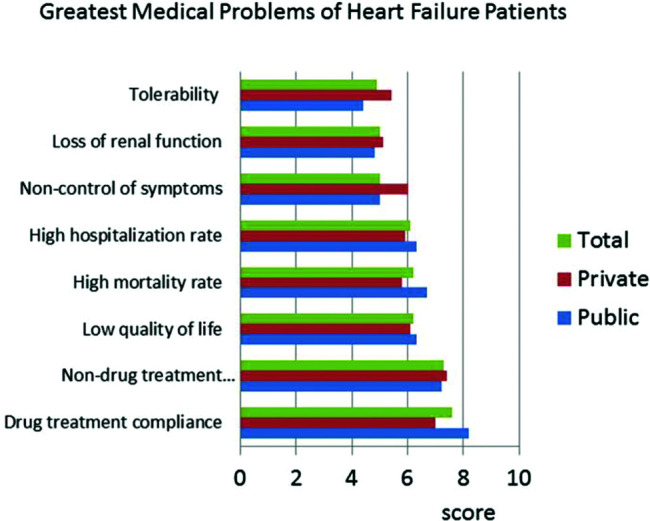

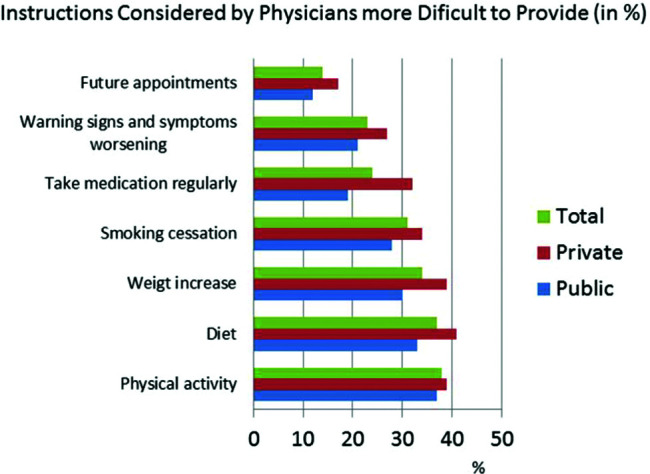

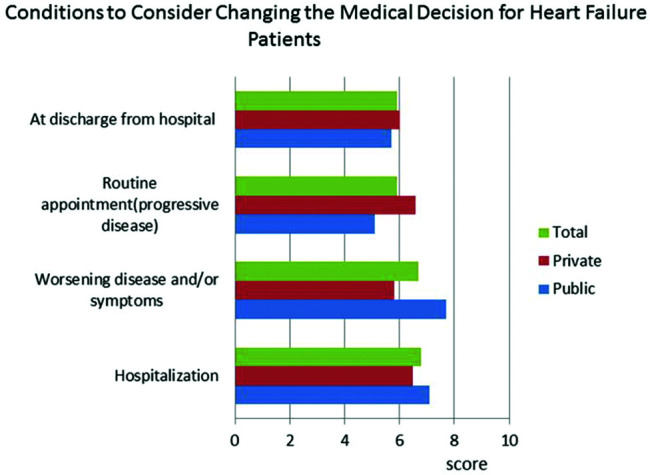

The responses to the question "What are the most important criteria for evaluating disease progression?" were ranked by level of importance by the respondents. The results showed that in both public and private centers, clinical signs and symptoms received the highest scores, followed by hemodynamic instability (Figure 1). BNP was less important in centers with an HF specialized team. Questions about HF treatment goals showed that survival, symptoms, quality of life, and hospitalization were important in descending order (Figure 2). Drug treatment compliance was the greatest medical challenge in treating HF patients (Figure 3). The instructions considered by physicians as the most difficult to provide according to highest to lowest percent were those for physical activity, diet, prevention of weight gain, and smoking cessation (Figure 4). Difficulties with compliance were more frequent in private settings patients. Overall, hospitalization, worsening of symptoms, routine appointments, and hospital discharge were considered as signs for treatment optimization (Figure 5).

Figure 1. Perceptions of doctors in centers treating heart failure (HF) regarding a criteria for evaluation of HF disease progression using a score in total, private, and public HF patients in HF specialized and all centers.

Figure 2. Perceptions of doctors in centers treating heart failure (HF) patients about goals of HF treatment using a score for total, private, and public settings.

Figure 3. Perceptions of doctors in centers treating heart failure (HF) regarding the greatest medical problems of HF patients using a score for total, private, and public settings.

Figure 4. Perceptions of doctors in centers treating heart failure (HF) regarding instructions considered more difficult to provide according to percent in total, private, and public settings.

Figure 5. Perceptions of doctors in centers treating heart failure (HF) regarding the importance of conditions that lead to change in the management of HF patients.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, our results are the first summary of HF-DMP characteristics from cardiology centers involved in the management of HF patients in Brazil. We found that the heterogeneity of HF-DMPs may affect the care delivered. HF patients in public care centers had a different profile compared to patients in private care concerning the severity and etiology of their disease. Educational programs and multidisciplinary components were more frequently reported in public care settings. In private centers, hospitalization and 6-month mortality rates were the most frequently used key performance indicators. In the private care system, ambulatory cardiologists were responsible for most medical decisions and HF treatment initiation in hospitalized patients, whereas in public centers, the hospital cardiology team made most decisions. Limitations concerning the patient instructions were reported. There was no consensus about the best moment to consider changing methods for HF management.

Public and private care coexist in many countries around the world. Unfortunately, there is no published data on HF treatment in private and public care in the same country to compare our results. One explanation for the greater HF case severity in patients treated in public centers, along with a higher prevalence of Chagas disease, might be the low income and restricted access to cardiology care. The higher prevalence of more severe cases of HF in public centers may demand more surgical treatments and multidisciplinary care components. Multidisciplinary programs may be more effective in treating high-risk patients and, consequently, more reasonable in public settings (8). From an economic point of view, the lack of reimbursement may be a limiting factor for the existence of multidisciplinary teams in private settings.

The heterogeneity of HF-DMPs in the present study is similar to previously reported data (8). A vast range of combinations regarding HF care models have been described, varying from a single educational session before discharge; a single educational home visit by a nurse specialist and regular telephone follow-up; or a multidisciplinary intervention centralized in a dedicated facility, with or without primary care interaction (4).

The reported percentage of HF educational programs for patients and caregivers in private centers is considered low when compared to published data from selected countries (9). Accordingly, the percentage of nurses who were the main providers of patient education in inpatient and outpatient settings was lower in private care (10). In the present study, the observed percentage of educational programs for caregivers was even lower than that from published data, both for public and private centers. It is conceivable that this may be associated with poorer clinical outcomes since caregivers contribute to HF patient care and management but without proper education, some of their practices are not evidence-based (11). Conversely, caregiver training for early recognition of symptoms and signs of worsening HF may be effective in reducing hospitalizations (12).

The low use of non-invasive monitoring programs (home monitoring or telephone interviews) in both private and public care systems could be explained by the mixed and controversial evidence, which show poor efficacy for reducing serious negative outcomes in HF (13). On the other hand, we observed higher rates of HF instructions at hospital discharge, despite inconsistent or controversial results from previous studies (14). It is possible that instructions and follow-up planning at discharge are tailored according to the characteristics of each institution and patient population, creating more effective follow-up. In addition, instructions and planning at discharge are not too complex to be implemented in clinical practice.

We observed a non remarkable rate of cardiac rehabilitation availability (54% of centers), which was higher in public centers (69% in public centers versus 39% in private centers, p=0.016). These data probably reflect the current recommendations (15), despite the neutral results of the HF-ACTION trial on mortality which were corroborated by a recent meta-analysis (16-19). However, according to the updated Cochrane review, exercise-based rehabilitation reduces the risk of hospital admissions and confers important improvements in health-related quality of life. However, it is important to consider that the availability of rehabilitation services does not mean that a high percentage of patients are actually under rehabilitation because the adherence rate to exercise is usually modest (20). In addition, our survey showed that instructions for exercise were one of the most difficult to provide. This is an important point, as previous studies have reported that one-third of HF patients had a low level of physical activity in their daily life (21). Furthermore, only a small number of the participating centers used a quality of life assessment to evaluate treatment success.

One positive result from the present study was that the prescribed HF treatment and its goals are in accordance with guideline-directed medical therapy for HF (GDMT-HF) (22). Unfortunately, the data also showed that physicians mostly consider changing or introducing new medications when patients are hospitalized or when diagnosis indicates worsening disease and/or symptoms. These findings might partly explain why in a contemporary US registry, most eligible HF patients with reduced ejection fraction did not receive target doses of medical therapy at any time point during follow-up, and few patients had doses increased over time (23).

Limitations

This study has several limitations, many that are typical limitations of using a survey for data collection (24). Despite these limitations, surveys are very important tools to understand the current practice of medicine around the world. This study may be limited by its cross-sectional nature and therefore could be biased in its selection of centers, sampling approaches, and variables, which could overestimate or underestimate true values. The study population was limited to selected cardiologists belonging to HF centers and did not include general practitioners or other physicians involved in the care of HF patients. Other limitations include the limited generalizability of the results, since the study was conducted in selected centers. No data monitoring was performed since the survey was self-reported. Significant results from this analysis should be confirmed in prospective studies. In addition, recent advances in the pharmacological treatment of HF, such as angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) (i.e. valsartan/sacubitril), dapaglifozine, and sinoatrial node modulators (ivabradine) were not included in this survey (25,26). Data supporting answers for the questionnaire were not collected; however, this is a standard limitation for self-reported surveys. The survey answers were anonymous to reduced response-bias and encourage responders to provide accurate and honest answers since they may not feel comfortable unfavorably presenting themselves.

Despite these limitations, the strength of this study includes the stratification of HF data representing the daily clinical practice of HF management in Brazil.

CONCLUSIONS

HF-DMPs are heterogeneous, with many components still underutilized in private practice. The present survey extends our understanding of HF management in Brazil. Based on our study, strategies can be developed to improve outcomes in patients with HF. In addition, the characteristics of HF centers can be influenced, based on whether they are in a private or public setting. From an optimistic perspective, our results demonstrate that HF patient care is established on an evidence-based approach, attempting to ensure the achievement of pharmacological GDMT goals independent of the center setting. However, the characteristics of non-pharmacological management are heterogeneous despite GDMT-HF. The diverse features of the HF-MDPs in multiple centers managing HF could partially reflect the lack of consistent data or controversial results from prospective trials, mainly for educational and monitoring programs, multidisciplinary team components, and rehabilitation.

The findings demonstrate that physicians mostly consider shifting or introducing new therapies when patients are hospitalized or the symptoms are striking. Thus, there is an evident need for improvements in education for both physicians and patients.

Highlights

In general, the components of DMPs in heart failure (HF) clinics are heterogeneous.

Non-private HF and multidisciplinary care were associated with a higher percentage of dedicated service to HF, education, and guideline-directed medical therapy for HF treatment.

Physicians considered changing or introducing new medications mostly when patients were hospitalized or when diagnosis indicated disease and/or symptoms worsening.

Adherence to drug treatment and non-drug treatment were the greatest medical challenges associated with HF treatment.

The planning of new strategies for HF care should consider DMP-HF characteristics and clinical decision-making processes to improve HF patient care.

Conflicts of Interest. Edimar Alcides Bocchi: Consulting Fee: Servier, Astra-Zeneca; Subsidized Travel/Hotel/Registration Fees: Servier; Membership in Steering Committee: Servier, Novartis; Contracted Research: Jansen, Bayer/Merck; Honoraria: Novartis; Henrique Turin Moreira, nothing to declare; Juliana Sanajotti Nakamuta; Novartis employees; Marcus Vinicius Simões; Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Honoraria Novartis, Servier, EMS.

CLIMB-HF study investigators (in alphabetical order). Collaborators who agreed to be mentioned and included in the CLIMB-HF Study Group (according to information obtained by Novartis):

Alberto de Almeida Las Casas (Hospital do Coração Anis Rassi), Altamiro Reis da Costa (Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul), Amberson Vieira de Assis (Instituto de Cardiologia de Santa Catarina), André Rodrigues Durães(Hospital Ana Nery/UFBa), Antonio Carlos Pereira-Barretto (Instituto do Coração - InCor-SP), Antonio Delduque de Araujo Ravessa (Centro Médico), Ariane Vieira Scarlatelli Macedo (Rede Mater Dei de Saúde), Bruno Biselli (Hospital Sírio-Libanês), Carolina Maria Nogueira Pinto (Total Care - AMIL - São Paulo), Conrado Roberto Hoffmann Filho (Hospital Regional Hans Dieter Schimidt), Costantino Roberto Costantini (Hospital Cardiológico Costantini), Dirceu Rodrigues Almeida (Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) - Hospital São Paulo), Edval Gomes dos Santos Jr (Hospital Dom Pedro de Alcântara), Erwin Soliva Junior (Hospital Universitário do Oeste do Paraná), Estevão Lanna Figueiredo (Hospital Lifecenter - Belo Horizonte -MG), Felipe Neves de Albuquerque (Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade do Estudo do Rio de Janeiro), Felipe Paulitsch (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande), Fernando Carvalho Neuenschwander (Hospital Vera Cruz - Belo Horizonte), Jos� Albuquerque de Figueiredo Neto (Universidade Federal do Maranhão), Flavio de Souza Brito (Total Care - AMIL - São Paulo), Heno Ferreira Lopes (Instituto do Coração - InCor-SP), Humberto Villacorta (Universidade Federal Fluminense), João David de Souza Neto (Hospital de Messejana Dr. Carlos Alberto Studart Gomes), João Mariano Sepulveda (Instituição Medicare), José Carlos Aidar Ayoub (Instituto de Moléstias Cardiovasculares Rio Preto Ltda), José F. Vilela-Martin (Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto (FAMERP), Juliano Novaes Cardoso (Hospital Santa Marcelina), Laercio Uemura (Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Centro do Coração de Londrina), Lidia Zytynski Moura (Santa Casa de Curitiba - PUCPR), Lilia Nigro Maia (Hospital de Base/Faculdade de Medicina de Rio Preto (FAMERP), Lucia Brandão de Oliveira (Clínica de Insuficiência Cardíaca do Centro Universitário Serra dos =rgãos (UNIFESO)), Lucimir Maia (Hospital Regional do Guará), Luís Beck da Silva (Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre), Luís Henrique Wolff Gowdak (Instituto do Coração - InCor-SP), Luiz Claudio Danzmann (Universidade Luterana do Brasil), Marcus Andrade (Hospital Santa Izabel - Santa Casa de Misericórdia da Bahia), Maria Christiane Valeria Braga Braile-Sternieri (Instituto Domingo Braile), Maria da Consolação Vieira Moreira (Hospital das Clínicas da UFMG), Olimpio R. França Neto (Instituto Paranaense de Cardiologia), Otavio Rizzi Coelho Filho (Hospital das Clínicas da UNICAMP), Paulo Frederico Esteves (Hospital Santa Mônica, Divinópolis, MG); Priscila Raupp-da-Rosa (Hospital Divina Providência), Ricardo Jorge de Queiroz e Silva (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte), Ricardo Mourilhe-Rocha (Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro), Ruy Felipe Melo Viégas (Universidade de Taubaté (UNITAU)), Salvador Rassi (Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás), Sandrigo Mangili (Hospital Municipal da Vila Santa Catarina), Sergio Emanuel Kaiser (Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto), Silvia Marinho Martins (Ambulatório de Doença de Chagas e Insuficiência Cardíaca - PROCAPE - Universidade de Pernambuco), Vitor Sergio Kawabata (Hospital Universitário da Universidade de São Paulo).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bocchi EA was responsible for the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafting and review. Moreira HT was responsible for the data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafting and review. Nakamuta JS was responsible for the acquisition of data, study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafting and review. Simões MV was responsible for the data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafting and review. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

APPENDIX. Supplementary Table S1 - Questionnaire

I. Site data

Institution’s Name: City UF [Federative Unit] / State:

-

Type of Service: (Public) / (Private)

Note: even if you attend different services, please fulfill this questionnaire according to the type of service you selected (public or private). If you prefer, one can fulfill a second questionnaire with the information of the other service.

II. Physical and professional structure of the customer service for Heart Failure

Approximate number of patients with HF under follow-up: ( )

Approximate number of patients with HF attended per week: ( )

What is the average monthly number of hospitalizations due to HF in the service?

-

Regarding the outpatient structure, which items are present in your service (select the most applicable item)?

□General outpatient unit

□Cardiology outpatient unit

□HF subspecialized outpatient unit

□HF subspecialized outpatient and hospitalization units

-

In what way is the outpatient service structured?

□Hospital outpatient facilities/services

□Private practice

□Both (hospital outpatient facility/service and private practice)

-

What are the types of treatment available in your service (check all applicable types):

□Clinical treatment

□ICD (implantable cardioverter defibrillator) and Resynchronizer

□Surgical treatment, except for transplantation

□Surgical treatment and transplantation

□Circulatory support

Does the service have multiprofessional care? (Yes/No)

If it has a multiprofessional service, check which ones and how many professionals in each area.

Cardiology: N=□

Nursing, N=□

Psychology, N=□

Nutrition, N=□

Physiotherapy, N=□

Pharmacist, N=□

Nephrology, N=□

Cardiac Surgeon, N=□

Exercise Physical Educator/Physiotherapist, N=□

Social worker, N=□

Other, N=□

III. Patients and the disease

-

According to your perception, what is the approximate percentage of patients in NYHA functional classes?

Functional class I : __%

Functional class II : __%

Functional class III : __%

Functional class IV : __%

-

According to your perception, what is the approximate percentage of the main HF etiologies of patients in your service?

Ischemic: __%

Valvulopathies __%

Hypertensive: __%

Chagas Disease: __%

Idiopathic: __%

Peripartum: __%

Cardiotoxicity: __%

-

Other cardiomyopathies: __%

□Is BNP used in your service? (select all applicable items)

□No because we do not have access.

□No because it is not considered essential.

□Yes, to help in the diagnosis.

□Yes, to determine the prognosis.

□Yes, to help define the treatment.

□Yes, to monitor the patient.

-

In general, who has been initiating HF treatment in your patients? (enter an estimated percentage)

□Hospital cardiologist (___%)

□Outpatient facility/practice cardiologist (___%)

□General practitioner (___%)

□Intensive care physician (___%)

□Geriatrician (___%)

□Other specialties (nephrologist, endocrinologist, emergency physician, other) (___%)

-

What are the most important criteria for assessing disease progression? Number in order of importance (1 being the most important and 6 being the less important; number as “zero” if you do not consider it important).

□Clinical signs and symptoms

□Biomarkers (BNP, NT-proBNP)

□Renal function

□Oxygen saturation (arterial blood gas)

□Hemodynamic stability

□Other

IV. Heart Failure Treatment

-

What is your goal in the treatment of HF patients?

Number in order of importance (1 being the most important and 5 being the less important).

□Alleviate HF signs and symptoms (e.g., edema, dyspnea, etc.)

□Prevent hospitalization

□Improve survival rate

□Improve quality of life

□Other

-

What are the greatest medical problems of HF patients despite the currently available treatments?

Number in order of importance (1 being the most important and 8 being the less important; number as “zero” if you do not consider it important).

□Drug treatment compliance

□Non-drug treatment compliance (non-drug actions)

□Tolerability

□High mortality rate

□Low quality of life

□High rehospitalization rate

□Non-control of symptoms

□Loss of renal function

-

What is the most commonly used base treatment for HF patients? (Select all applicable items)

□ ACE inhibitor □ ARB □ Beta Blocker □ Spironolactone □ Digoxin □ Diuretics □ Vasodilators

-

What is the percentage of HF patients receiving the target dose based on the guideline recommendations?

(___%) (numerical field)

□ I cannot estimate

-

In which conditions would you consider changing the base conduct of a HF patient?

Number in order of importance (1 being the most important and 4 being the less important; number as “zero” the situations that you would not change the treatment).

□On a routine appointment (since it is a progressive disease).

□When the patient was hospitalized.

□After hospitalization, the patient is discharged from the hospital and returns to the practice.

□When the diagnosis indicates worsening disease and/or symptoms.

Are there educational programs about the disease, such as classes and lectures, for patients? □ yes □ no

Are there educational programs about the disease, such as classes and lectures, for caregivers? □ yes □ no

Is instruction given regarding written discharge for patients and/or caregivers? □ yes □ no

-

If yes, who gives this instruction?

□Nursing

□Pharmacist

□Physician responsible for discharge

□Other

-

During patient instruction, which of the instructions below you consider more difficult to provide (e.g., due to lack of time or patient acceptance):

Select all the applicable items.

□Instruction about diet

□Instruction about the need to take the medications regularly

□Instruction about physical activities

□Instruction about warning signs and worsening symptoms

□Instruction about weight increase

□Instruction about smoking cessation

□Instruction about future appointments.

-

Regarding patient monitoring programs:

□Not available

□An educational program

□There is a “non-medical” outpatient specialized monitoring program.

□There is a remote monitoring program via telephone or another appropriate method.

□There is a home monitoring program.

-

Does the service follow any guidelines? (select only the relevant items that encompass the entire service)

□The service does not follow a systematic and regular basis.

□ESC

□AHA

□DEIC

□Assistance intra-institutional protocol (institution’s own protocol)

□Other

-

Is any questionnaire on the quality of life regularly used?

□KCCQ

□Minnesota

□Other

□None

Is there a cardiac rehabilitation service? □ Yes □ No

-

What are the key performance indicators related to HF in your service? (checking all applicable items)

□I do not know

□There are no objective key performance indicators at the moment in my service

□Hospital mortality rate

□Mortality rate after six months

□Rehospitalization rate after 30 days

□Rehospitalization rate after 90 days

□Hospital length of stay

□Other

-

Who determines the conduct of a patient with acute heart failure (AHF) during hospitalization? (e.g., treatment regimen)

Please estimate the percent (numerical field).

□Hospital cardiology team: ___%

□Cardiologist following the patient in the outpatient facility: ___%

□Intensive care physician (while the patient is in the ICU): ___%

(for physicians) Would you like to be mentioned in a potential future publication (as acknowledgements)? If yes, please provide the information below.

Name: _____ (free field); Email: _____ (free field).

Supplementary Table S2. Delivered care for heart failure patients in participating centers according to availability of multidisciplinary care.

| Multidisciplinary Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Available (n=23) | Available (n=64) | p-value | |

| BNP dosage | 70% (14/20) | 84% (48/57) | ns |

| Centers with BNP | |||

| Help in the diagnosis | 79% (11/14) | 69% (33/48) | ns |

| Determine the prognosis | 71% (10/14) | 56% (27/48) | ns |

| Help the treatment | 7% (1/14) | 42% (20/48) | 0.023 |

| Monitoring | 57% (8/14) | 60% (29/48) | ns |

| Centers with no BNP | |||

| Lack of access | 83% (5/6) | 89% (8/9) | ns |

| Considered not essential | 16% (1/6) | 22% (2/9) | ns |

| Education program for patient | 6% (1/18) | 42% (22/53) | 0.004 |

| Education program for caregivers | 11% (2/9) | 28% (15/53) | ns |

| Written instructions at hospital discharge | 68% (13/19) | 89% (48/54) | 0.038 |

| By Doctor | 62% (10/11) | 58% (26/45) | ns |

| By Nurse | 38% | 40% | |

| By Others | 0% (0/11) | 2% (1/45) | |

| Patient monitoring programs | 6% (1/16) | 49% (25/51) | 0.001 |

| Using monitoring program | |||

| At ambulatory using non-doctorspecialized monitoring | 0% (0/17) | 26% (13/51) | 0.028 |

| At distance using phone or other method | 6% (1/17) | 24% (9/51) | ns |

| Regular use of HF guidelines | 83% (15/18) | 92% (48/52) | ns |

| DEIC | 61% (11/18) | 38% (20/52) | ns |

| ESC | 5% (1/18) | 19% (10/52) | |

| AHA | 17% (3/18) | 21% (11/52) | |

| Institution's own protocol | 0% (0/18) | 12% (6/52) | |

| Other guidelines | 0% (0/18) | 2% (1/52) | |

| Not following guidelines | 17% (3/18) | 8% (4/52) | |

| Using quality of life questionnaire | 35% (6/17) | 24% (12/50) | ns |

| KCCQ | 3% (1/17) | 3% (3/50) | ns |

| MLHFQ | 29% (5/17) (5 out of 17) | 18% (9/50) (9 out of 50) | ns |

| Other | 0% (0/17) | 4% (2/50) | ns |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 17% (3/18) | 69% (33/50) | <0.001 |

| Key performance indicators | 40% (6/15) | 55% (26/47) | ns |

| Hospital mortality | 27% (4/15) | 32% (15/47) | ns |

| 6-month mortality | 13% (2/15) | 21% (10/47) | ns |

| 30-day hospitalization after discharge | 13% (2/15) | 38% (18/47) | ns |

| 90-day hospitalization after discharge | 7% (1/15) | 17% (8/47) | ns |

| Hospitalization duration | 7% (1/15) | 30% (14/47) | 0.09 |

| Other | 0% (0/17) | 4% (2/47) | ns |

| Medical decision in hospitalized patient in decompensated HF | |||

| By hospital cardiology team | 76% | 44% | <0.001 |

| By cardiologist who cares for the patient in the outpatient clinic | 18% | 43% | <0.001 |

| By intensive care unit doctors if admitted in intensive care unit | 6% | 13% | 0.023 |

| Beginning of HF treatment | |||

| Cardiologist in hospital | 40% | 38% | ns |

| Cardiologist in ambulatory | 43% | 42% | ns |

| General practitioner | 5% | 11% | 0.078 |

| Intensive care doctor | 6% | 4% | ns |

| Geriatrics | 2% | 2% | ns |

| Others | 4% | 3% | ns |

| Prescribed HF treatment | |||

| ACE-I | 100% (18/18) | 94% (51/54) | ns |

| ARBs | 78% (14/18) | 87% (47/64) | ns |

| Β-blocker | 89% (16/18) | 93% (50/54) | ns |

| Spironolactone | 100% (15/18) | 93% (50/54) | ns |

| Digoxin | 33% (6/18) | 43% (23/54) | ns |

| Diuretics | 78% (14/18) | 91% (49/54) | ns |

| Vasodilators | 55% (10/18) | 52% (28/54) | ns |

| Patients with target doses of medication according guidelines (%) | 45% | 61% | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; Specialized HF care considered (in-hospital or outpatient); HF, heart failure; HF-DMP, Disease Management Program for HF; Centers with at least one multidisciplinary member, centers having at least one of the following professions: cardiology, nursing, physiotherapy and/or physical educator or nutritionist; HF, heart failure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DEIC, Heart Failure Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; MDP, multidisciplinary program; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire; ACE-I Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Supplementary Table S3. Delivered care for heart failure patients in participating centers according to heart failure subspecialized care.

| HF Subspecialized Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Available (n=48) | Available (n=42) | p-value | |

| BNP dosage | 65% (31/48) | 58% (33/57) | ns |

| Centers with BNP | |||

| Help in the diagnosis | 71% (22/31) | 73% (24/33) | ns |

| Determine the prognosis | 65% (20/31) | 58% (19/33) | ns |

| Help the treatment | 42% (13/31) | 24% (8/33) | ns |

| Monitoring | 62% (19/31) | 55% (18/33) | ns |

| Centers with no BNP | |||

| Lack of access | 100% (7/7) | 75% (6/8) | ns |

| Considered not essential | 0% (0/6) | 38% (3/8) | ns |

| Education program for patient | 53% (18/34) | 41% (16/39) | ns |

| Education program for caregivers | 17% (6/35) | 31% (12/39) | ns |

| Written instructions at hospital discharge | 77% (27/35) | 90% (36/40) | ns |

| By Doctor | 79% (19/24) | 56% (19/34) | ns |

| By Nurse | 21% (5/24) | 41% (14/34) | |

| By Others | 0% (0/24) | 2.9% (1/34) | |

| Patient monitoring programs | 23% (7/31) | 51% (20/39) | 0.014 |

| Using monitoring program | |||

| At ambulatory using non-doctorspecialized monitoring | 3.2% (1/31) | 33% (13/39) | 0.002 |

| At distance using phone or other methods | 10% (3/31) | 18% (7/39) | ns |

| Regular use of HF guidelines | 84% (27/32) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| DEIC | 52% (14/27) | 45% (17/38) | ns |

| ESC | 26% (7/27) | 21% (8/38) | |

| AHA | 19% (5/27) | 18% (7/38) | |

| Institution's own protocol | 3.7% (1/27) | 13% (5/38) | |

| Other guidelines | 0% (0/27) out of 27) | 2.6% (1/38) | |

| Not following guidelines | 19% (5/27) | 5.3% (2/38) | |

| Using quality of life questionnaire | 23% (7/31) | 29% (11/38) | ns |

| KCCQ | 6.5% (2/31) | 5.3% (2/38) | ns |

| MLHFQ | 16% (5/31) | 24% (9/38) | ns |

| Other | 3.2% (1/31) | 2.6% (1/38) | ns |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 27% (8/30) | 76% (29/38) | <0.001 |

| Key performance indicators | 50% (14/28) | 56% (20/36) | ns |

| Hospital mortality | 25% (7/28) | 36% (13/36) | ns |

| 6-month mortality | 18% (5/28) | 22% (8/36) | ns |

| 30-day hospitalization after discharge | 25% (7/28) | 39% (14/36) | ns |

| 90-day hospitalization after discharge | 4% (1/28) | 22% (8/36) | 0.066 |

| Hospitalization duration | 18% (5/28) | 30% (11/36) (11 out of 36) | ns |

| Other | 0% (0/28) | 6% (2/36) | ns |

| Medical decision in hospitalized patient in decompensated HF | |||

| By hospital cardiology team | 41% | 45% | <0.001 |

| By cardiologist who cares for the patient in the outpatient clinic | 45% | 42% | <0.001 |

| By intensive care unit doctors if admitted in intensive care unit | 14% | 12% | 0.067 |

| Beginning of HF treatment | |||

| Cardiologist in hospital | 41% | 45% | <0.001 |

| Cardiologist in ambulatory | 41% | 31% | <0.001 |

| General practitioner | 6% | 14% | <0.001 |

| Intensive care doctor | 9% | 3% | <0.001 |

| Geriatrics | 1% | 2% | ns |

| Others | 2% | 4% | ns |

| Prescribed HF treatment | |||

| ACE-I | 97% (33/34) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| ARBs | 79% (27/34) | 88% (35/40) | ns |

| Β-blocker | 97% (33/34) | 88% (35/40) | ns |

| Spironolactone | 91% (31/34) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| Digoxin | 24% (8/34) | 53% (21/40) | 0.017 |

| Diuretics | 82% (28/34) | 93% (37/40) | ns |

| Vasodilators | 34% (13/34) | 63% (25/40) | 0.037 |

| Patients with target doses of medication according guidelines (%) | 46% | 68% | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; Specialized HF care considered (in-hospital or outpatient); HF, heart failure; HF-DMP, Disease Management Program for HF; Centers with at least one multidisciplinary member, centers having at least one of the following professions: cardiology, nursing, physiotherapy and/or physical educator or nutritionist; HF, heart failure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DEIC, Heart Failure Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; MDP, multidisciplinary program; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire; ACE-I Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Supplementary Table S4. Delivered care for heart failure patients in participating centers comparing centers according to higher specialized multidisciplinary care.

| HF higher specialized multidisciplinary care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Available (n=23) | Available (n =42 ) | p-value | |

| BNP dosage | 70% (14/20) | 90% (37/41) | 0.066 |

| Centers with BNP | |||

| Help in the diagnosis | 79% (11/14) | 70% (26/37) | ns |

| Determine the prognosis | 71% (10/14) | 60% (22/37) | ns |

| Help the treatment | 7% (1/14) | 38% (14/37) | 0.041 |

| Monitoring | 57% (8/14) | 60% (22/37) | ns |

| Centers with no BNP | |||

| Lack of access | 100% (7/7) | 75% (6/8) | ns |

| Considered not essential | 0% (0/6) | 38% (3/8) | ns |

| Education program for patient | 53% (18/34) | 41% (16/39) | ns |

| Education program for caregivers | 17% (6/35) | 31% (12/39) | ns |

| Written instructions at hospital discharge | 77% (27/35) | 90% (36/40) | ns |

| By Doctor | 79% (19/24) | 56% (19/34) | Ns |

| By Nurse | 21% (5/24) | 41% (14/34) | |

| By Others | 0% (0/24) | 3% (1/34) | |

| Patient monitoring programs | 23% (7/31) | 51% (20/39) | 0.014 |

| Using monitoring program | |||

| At ambulatory using non-doctorspecialized monitoring | 3% (3/11)(1 out of 31) | 33% (13/39)(13 out of 39) | 0.002 |

| At distance using phone or other method | 10% (3/31) | 18% (7/39) | ns |

| Regular use of HF guidelines | 84% (27/32) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| DEIC | 52% (14/27) | 45% (17/38) | ns |

| ESC | 26% (7/27) | 21% (8/38) | |

| AHA | 19% (5/27) | 18% (7/38) | |

| Institution's own protocol | 3% (1/27) | 13% (5/38) | |

| Other guidelines | 0% (0/27) | 2.6%(1/38) | |

| Not following guidelines | 19% (5/27) | 5% (2/38) | |

| Using quality of life questionnaire | 23% (7/31) | 29% (11/38) | ns |

| KCCQ | 7% (2/31) | 5% (2/38) | ns |

| MLHFQ | 16% (5/31) | 24% (9/38) | ns |

| Other | 3% (1/31) | 3% (1/38) | ns |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 27% (8/30) | 76% (29/38) | <0.001 |

| Key performance indicators | 50% (14/28) | 56% (20/36) | ns |

| Hospital mortality | 25% (7/28) | 36% (13/36) | ns |

| 6-month mortality | 18% (5/28) | 22% (8/36) | ns |

| 30-day hospitalization after discharge | 25% (7/28) | 39% (14/36) | ns |

| 90-day hospitalization after discharge | 4% (1/28) | 22% (8/36) | ns |

| Hospitalization duration | 18% (5/28) | 31% (11/36) | ns |

| Other | 0% (0/28) | 6% (2/36) | ns |

| Medical decision in hospitalized patient in decompensated HF | |||

| By hospital cardiology team | 42% | 33% | <0.001 |

| By cardiologist who cares for the patient in the outpatient clinic | 45% | 57% | <0.001 |

| By intensive care unit doctors if admitted in intensive care unit | 13% | 10% | 0.002 |

| Beginning of HF treatment | |||

| Cardiologist in hospital | 40% | 45% | 0.009 |

| Cardiologist in ambulatory | 43% | 27% | <0.001 |

| General practitioner | 5% | 16% | 0.006 |

| Intensive care doctor | 6% | 5% | ns |

| Geriatrics | 2% | 2% | ns |

| Others | 4% | 5% | ns |

| Prescribed HF treatment | |||

| ACE-I | 97% (33/34) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| ARBs | 79% (27/34) | 88% (35/40) | ns |

| Β-blocker | 97% (33/34) | 88% (35/40) | ns |

| Spironolactone | 91% (31/34) | 95% (38/40) | ns |

| Digoxin | 24% (8/34) | 53% (21/40) | 0.017 |

| Diuretics | 82% (28/34) | 93% (37/40) | ns |

| Vasodilators | 38% (13/34) | 63% (25/40) | 0.037 |

| Patients with target doses of medication according guidelines (%) | 45% | 65% | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; Specialized HF care considered (in-hospital or outpatient); HF, heart failure; HF-DMP, Disease Management Program for HF; Centers with at least one multidisciplinary member, centers having at least one of the following professions: cardiology, nursing, physiotherapy and/or physical educator or nutritionist; HF, heart failure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DEIC, Heart Failure Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; MDP, multidisciplinary program; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire; ACE-I Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Alberto de Almeida Las Casas, Altamiro Reis da Costa, Amberson Vieira de Assis, André Rodrigues Durães, Antonio Carlos Pereira-Barretto, Antonio Delduque de Araujo Ravessa, Ariane Vieira Scarlatelli Macedo, Bruno Biselli, Carolina Maria Nogueira Pinto, Conrado Roberto Hoffmann Filho, Costantino Roberto Costantini, Dirceu Rodrigues Almeida, Edval Gomes dos Santos, Jr, Erwin Soliva, Junior, Estevão Lanna Figueiredo, Felipe Neves de Albuquerque, Felipe Paulitsch, Fernando Carvalho Neuenschwander, José Albuquerque de Figueiredo, Neto, Flavio de Souza Brito, Heno Ferreira Lopes, Humberto Villacorta, João David de Souza, Neto, João Mariano Sepulveda, José Carlos Aidar Ayoub, José F. Vilela-Martin, Juliano Novaes Cardoso, Laercio Uemura, Lidia Zytynski Moura, Lilia Nigro Maia, Lucia Brandão de Oliveira, Lucimir Maia, Luís Beck da Silva, Luís Henrique Wolff Gowdak, Luiz Claudio Danzmann, Marcus Andrade, Maria Christiane Valeria Braga Braile-Sternieri, Maria da Consolação Vieira Moreira, Olimpio R França, Neto, Otavio Rizzi Coelho Filho, Paulo Frederico Esteves, Priscila Raupp-da-Rosa, Ricardo Jorge de Queiroz e Silva, Ricardo Mourilhe-Rocha, Ruy Felipe Melo Viégas, Salvador Rassi, Sandrigo Mangili, Sergio Emanuel Kaiser, Silvia Marinho Martins, and Vitor Sergio Kawabata

REFERENCES

- 1.Arundel C, Lam PH, Khosla R, Blackman MR, Fonarow GC, Morgan C, et al. Association of 30-Day All-Cause Readmission with Long-Term Outcomes in Hospitalized Older Medicare Beneficiaries with Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2016;129(11):1178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comín-Colet J, Enjuanes C, Lupón J, Cainzos-Achirica M, Badosa N, Verdú JM. Transitions of Care Between Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: Critical Steps in the Design of a Multidisciplinary Care Model for the Prevention of Rehospitalization. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016;69(10):951–61. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moser DK. Heart failure management: optimal health care delivery programs. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2000;18:91–126. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.18.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonarow GC. Heart failure disease management programs: not a class effect. Circulation. 2004;110(23):3506–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151101.17629.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocchi EA, Cruz F, Guimarães G, Pinho Moreira LF, Issa VS, Ayub Ferreira SM, et al. Long-term prospective, randomized, controlled study using repetitive education at six-month intervals and monitoring for adherence in heart failure outpatients: the REMADHE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1(2):115–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.107.744870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bocchi EA, da Cruz FDD, Brandão SM, Issa V, Ayub-Ferreira SM, Brunner la Rocca HP, et al. Cost-Effectiveness Benefits of a Disease Management Program: The REMADHE Trial Results. J Card Fail. 2018;24(10):627–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roccaforte R, Demers C, Baldassarre F, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Effectiveness of comprehensive disease management programmes in improving clinical outcomes in heart failure patients. A meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(7):1133–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gandhi S, Mosleh W, Sharma UC, Demers C, Farkouh ME, Schwalm JD. Multidisciplinary Heart Failure Clinics Are Associated With Lower Heart Failure Hospitalization and Mortality: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(10):1237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilmour J, Strong A, Chan H, Hanna S, Huntington A. Primary health care nurses and heart failure education: a survey. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6(3):229–37. doi: 10.1071/HC14229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundel S, Ea EE. An Educational Intervention to Evaluate Nurses' Knowledge of Heart Failure. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018;49(7):315–21. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20180613-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durante A, Paturzo M, Mottola A, Alvaro R, Vaughan Dickson V, Vellone E. Caregiver Contribution to Self-care in Patients With Heart Failure: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(2):E28–E35. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padula MS, D'Ambrosio GG, Tocci M, D'Amico R, Banchelli F, Angeli L, et al. Home care for heart failure: can caregiver education prevent hospital admissions? A randomized trial in primary care. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2019;20(1):30–8. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldgrab D, Balakumaran K, Kim MJ, Tabtabai SR. Updates in heart failure 30-day readmission prevention. Heart Fail Rev. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(2):177–87. doi: 10.1007/s10741-018-9754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grafft CA, McDonald FS, Ruud KL, Liesinger JT, Johnson MG, Naessens JM. Effect of hospital follow-up appointment on clinical event outcomes and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):955–60. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1439–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJ, Dalal HM, Lough F, et al. Exercise‐based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000163. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor RS, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJ, Dalal H, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(4):CD003331. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor RS, Walker S, Smart NA, Piepoli MF, Warren FC, Ciani O, et al. Impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure (ExTraMATCH II) on mortality and hospitalisation: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(12):1735–43. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pozehl BJ, McGuire R, Duncan K, Kupzyk K, Norman J, Artinian NT, et al. Effects of the HEART Camp Trial on Adherence to Exercise in Patients With Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2018;24(10):654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klompstra L, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. Physical activity in patients with heart failure: barriers and motivations with special focus on sex differences. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1603–10. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S90942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bocchi EA, Marcondes-Braga FG, Bacal F, Ferraz AS, Albuquerque D, Rodrigues Dde A, et al. [Updating of the Brazilian guideline for chronic heart failure - 2012] Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;98(1 Suppl 1):1–33. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2012001000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Vaduganathan M, Albert NM, et al. Titration of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2365–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones TL, Baxter MA, Khanduja V. A quick guide to survey research. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(1):5–7. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13511609956372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]