Abstract

Introduction

Acute myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 infection has been recognised as one important complication associated with in-hospital mortality. The potential dose–response effect of cardiac troponin (cTn) concentrations on adverse clinical outcomes has not been systematically studied. Hence, we will conduct a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the relationship between elevated cTn concentrations and in-hospital adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

We will search PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and ISI Knowledge via Web of Science databases, as well as preprint databases (medRxiv and bioRxiv), from inception to October 2021, to identify all retrospective and prospective cohorts and randomised controlled studies using related keywords. The primary outcome will be all-cause mortality during hospitalisation. The secondary outcome will be major adverse event (MAE). To conduct a dose–response meta-analysis of the potential linear or restricted cubic spline regression relationship between elevated cTn concentrations and all-cause mortality or MAE, studies with three or more categories of cTn concentrations will be included. Univariable or multivariable meta-regression and subgroup analyses will be conducted to compare elevated and non-elevated categories of cTn concentration. Sensitivity analyses will be used to assess the robustness of our results by removing each included study at one time to obtain and evaluate the remaining overall estimates of all-cause mortality or MAE.

Ethics and dissemination

In accordance with the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital, ethical approval was waived for this systematic review protocol. This meta-analysis will be disseminated through a peer-reviewing process for journal publication and conference communication.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020216059.

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, adult cardiology, myocardial infarction, COVID-19

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review and meta-analysis will be the first to comprehensively explore the potential linear or non-linear dose–response relationship between elevated cardiac troponin (cTn) concentrations and adverse clinical outcomes in COVID-19.

Further data on the prognostic outcomes of different cTn categories (three or more) in patients with COVID-19 are needed.

High-sensitive cTn measurements at different time points are suggested to identify the potential prognostic role of tiny acute myocardial injury (cTn concentrations between detection limit and URL) in patients with COVID-19.

The inclusion of both retrospective and prospective studies may result in potential bias.

The sample size in each study and the number of included studies may be relatively small.

Introduction

Acute myocardial injury has been recognised as one important complication associated with in-hospital morbidity and mortality in adult patients with COVID-19 infection.1 2 As of 31 October 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused 46 501 423 infections and 1 202 031 deaths in 215 countries worldwide.3

Some studies have shown that the incidence of acute myocardial injury is common, with an incidence of as much as 20%–40% based on cardiac troponin (cTn) concentrations,4 5 particularly in patients with obvious cardiovascular risk factors and severe COVID-19.6 7 Although the main target of COVID-19 is the respiratory system, the cardiovascular system could also be affected through the neurohumoral regulation of the cardiovascular system, unbalancing the myocardial oxygen supply and demand, with lung injury-induced hypoxia, acute systemic inflammatory reaction and cytokine storm.8–10

To date, different diagnostic thresholds of cTn concentrations for acute myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 have been proposed. Some studies did not use 1×upper reference limit (URL) as the cut-off value for cTn concentrations.11 Moreover, controversial prognostic relationships of acute myocardial injury with clinical outcomes have been published by various researchers using 1×URL for diagnosis.12 13 Additionally, COVID-19, a global pandemic that recently broke out, is associated with high mortality (with at least four times increased risk) and will have long-term coexistence with other diseases in humans.14 Accordingly, the optimal cut-off value of cTn concentration with prognostic relevance for acute myocardial injury needs to be identified to initiate prompt beneficial intervention in the future. However, there have been limited studies reporting the clinical outcomes of different categories of cTn concentrations in COVID-19. Hence, we will conduct a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the association between elevated cTn concentrations and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

Objectives

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to explore the potential optimal cut-off value of elevated cTn concentration for acute myocardial injury in order to predict adverse clinical outcomes in adult patients with COVID-19.

Methods and analysis

Search strategy

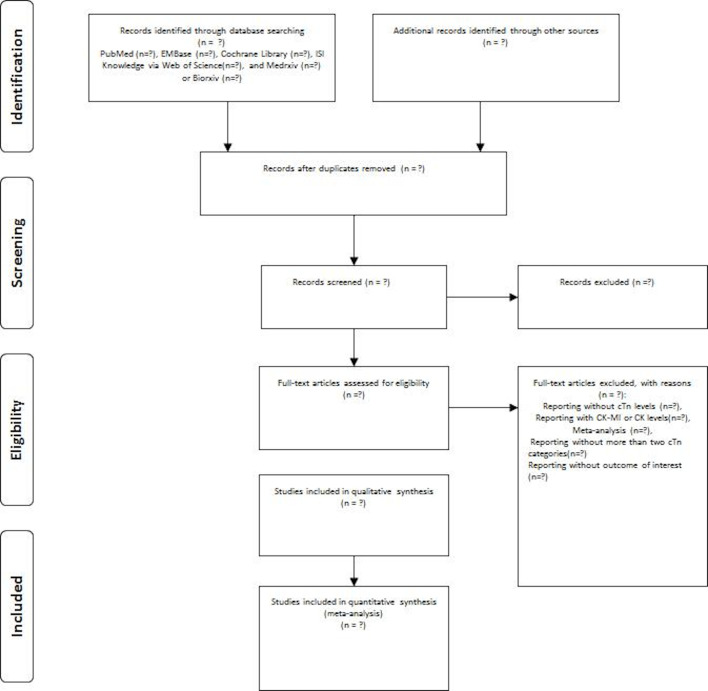

We will report this meta-analysis following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols.15 PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and ISI Knowledge via Web of Science databases, as well as preprint databases (medRxiv and bioRxiv), will be systematically searched from inception to October 2021. Table 1 shows the related search keywords. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the search process. This meta-analysis has been registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews).

Table 1.

Search strategy for PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, ISI Knowledge via Web of Science, and medRxiv or bioRxiv databases

| Database | Search items |

| PubMed | |

| Number | |

| #1 | ((cardiac injury) OR (myocardial injury)) OR (troponin) |

| #2 | (COVID-19) OR (SARS-CoV-2) |

| #3 | #1 and #2 |

| EMBASE | |

| #1 | cardiac AND injury OR (myocardial AND injury) OR troponin |

| #2 | ‘COVID-19 19’ OR ‘sars cov 2’ |

| #3 | #1 and #2 |

| Cochrane Library | |

| #1 | cardiac injury in All Text OR myocardial injury in All Text OR troponin in All Text |

| #2 | COVID-19 in All Text OR SARS-CoV-2 in All Text |

| #3 | #1 and #2 |

| ISI Knowledge via Web of Science | |

| #1 | TOPIC: (cardiac injury) OR TOPIC: (myocardial injury) OR TOPIC: (troponin) Timespan: all years. Databases: WOS, BIOSIS, KJD, MEDLINE, RSCI, SCIELO. Search language: auto. |

| #2 | TOPIC: (COVID-19) OR TOPIC: (SARS-CoV-2) Timespan: all years. Databases: WOS, BIOSIS, KJD, MEDLINE, RSCI, SCIELO. Search language: auto. |

| #3 | #1 and # 2 |

| medRxiv or bioRxiv | |

| #1 | title “cardiac injury” (match any words) and abstract or title “myocardial injury” (match any words) and full text or abstract or title “troponin” (match whole any) |

| #2 | title “COVID-19” (match any words) and abstract or title “SARS-CoV-2” (match any words) |

| #3 | #1 and #2 |

Figure 1.

Flow chart of trial search and selection. cTn, cardiac troponin; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB isoenzyme; CK, creatine kinase.

Type of participants

We will include adult patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection as study participants.

Type of studies

We will include all retrospective and prospective cohorts or randomised controlled studies that have reported an association between different cTn categories (three or more) and incidence of major adverse clinical outcomes. Trials published in English will be included. Studies where we were unable to extract the OR or the HR and the corresponding 95% CI will be excluded.

Type of outcomes

The primary outcome will be all-cause mortality during hospitalisation. The secondary outcome will be major adverse event (MAE). MAE is a combined endpoint during hospitalisation including all-cause death, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, acute kidney injury, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis or stroke. Additional outcomes will include incidence of heart failure, need for and duration of mechanical ventilation, and incidence of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Data extraction

Data will be extracted by two independent authors (YG and YZ), and a third author (HP) will make the final decision in case of discrepancies. The extracted data will include study design (author, publication year, country, sample size, percentage of positive cTn concentrations), patient characteristics (mean age, male proportion, race, body mass index, diabetes proportion, hypertension proportion, hyperlipidaemia proportion, smoking proportion, coronary artery disease proportion, previous myocardial infarction, chronic heart failure, history of atrial fibrillation, history of stroke or transient ischaemic accident, acute kidney dysfunction, chronic kidney dysfunction, history of lung disease, history of liver disease, beta-blocker usage, statin usage, ACE inhibitor usage, angiotensin receptor blocker usage, calcium channel blocker usage, aspirin usage), follow-up period, pattern, duration, number of total testing, detection kit for cTn, URL of cTn, detection limit of cTn, cut-off value of cTn and the different categories of cTn concentrations.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale will be used to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies.16

Data synthesis

The OR or the HR in each study will be extracted from the elevated versus non-elevated categories of cTn concentration for the pooled analysis. For studies that only provide log-rank test or Kaplan-Meier survival curve, the HR will be calculated based on time-to-event aggregate data.17 The referent category with non-elevated cTn will be the lowest cTn concentration in each study. Random-effect model using DerSimonian and Laird method will be employed to identify potential clinical inconsistency among the included studies in the pooled analysis. If one study reported multiple cTn categories (three or more), we will calculate the OR based on the number of cases and non-cases in all of the elevated categories and referent groups for the high versus low analysis. Univariable or multivariable meta-regression and subgroup analyses will be conducted to compare between elevated and non-elevated categories of cTn concentration, including study design, demographic characteristics and different types of cTn assay.18 Sensitivity analyses will be used to assess the robustness of our results by removing each included study at one time to obtain and evaluate the remaining overall estimates of all-cause mortality or MAE. Publication bias will be evaluated by Begg’s and Egger’s tests, and symmetry will be visualised using funnel plot. A dose–response meta-analysis of the potential linear or restricted cubic spline regression relationship between different categories of elevated cTn concentrations and all-cause mortality or MAE will be performed. For studies that only provide the numerical value of each category of elevated cTn concentrations, the related number of times of the corresponding URL in each study will be calculated. The average concentration of elevated cTn in each category will be estimated by the mean of the lower and upper concentrations. If the highest category has an open upper concentration, the mean concentration will be estimated to be 1.2× the lower concentrations.19–21 P<0.05 (two-sided) will be considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses will be performed in Stata V.10.0 software and RevMan V.5.0 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Discussion

Although the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (UDMI) defines acute myocardial injury as cTn concentrations >99th percentile URL under a broad clinical condition,22 some studies have used thresholds other than the URL,11 whereas others using URL have obtained negative findings in patients with COVID-19.12 13 Additionally, many studies have not used high-sensitive cTn assays and have only measured it once at an early time point, resulting in an underestimated incidence and extent of acute myocardial injury in COVID-19.

Recently, a meta-analysis has indicated that patients with COVID-19 with acute myocardial injury (mostly using URL as a cut-off) showed a nearly four times higher risk of mortality than those with non-acute myocardial injury.14 Mortality of as high as 80 times with acute myocardial injury has also been reported in an early univariable regression analysis.1 Therefore, an optimal cut-off value of cTn concentrations for acute myocardial injury needs to be explored for early risk stratification and prompt therapy initiation and thereby improve prognosis.23 Our previous analysis showed similar findings, where a cut-off value of cTn concentrations for acute myocardial injury lower than the Fourth UDMI cut-off value was proposed with prognostic relevance following elective percutaneous coronary intervention.20 Fortunately, there have been several studies on this important issue.24–26 Additionally, high-sensitive cTn measurements at different time points27 are encouraged to identify the potential prognostic role of tiny or subclinical acute myocardial injury (cTn concentrations between detection limit and URL) in patients with COVID-19 infection.28–31

The major strength of this systematic review and meta-analysis is comprehensively exploring for the first time the potential linear or non-linear dose–response relationship between cTn concentrations and adverse clinical outcomes in COVID-19. Moreover, the study will focus on the significance of subclinical or tiny acute myocardial injury below the URL level for early diagnosis in order to improve prognosis and reduce related mortality.28 In addition, we will try to provide some new evidence for the new diagnostic criterion of the COVID-19-related acute myocardial injury in the case of long-term coexistence of COVID-19 with human beings.

There are also limitations to our analysis. First, studies using retrospective and prospective design will be included, resulting in potential bias. Second, the sample size in each study may be small. Third, we could not rule out the potential influence of different types of detection kits and methods for cTn concentrations in the included studies. Fourth, our analysis may not be sufficient for diagnosis of myocardial infarctiondue to lack of additional evidence of myocardial ischaemia (electrocardiography, echocardiography, coronary CT or angiography) in accordance with the Fourth UDMI definition.

Ethics and dissemination

In accordance with the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital, ethical approval was waived for this systematic review protocol. This meta-analysis will be disseminated through a peer-reviewing process for journal publication and conference communication.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CZ, HP and JS contributed to the conception and design of the study and revision of the protocol. The manuscript was drafted by CZ. YG and YZ will independently search and select the eligible studies and extract the data from the included studies. LC and ZF will assess the methodological quality and the risk of bias. All authors approved the protocol publication.

Funding: This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2020-I2M-CoV19-003), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81970290 and no. 81760096).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:802–10. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worldometersinfo COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak, 2020. Available: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.2020

- 4.Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, et al. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2020;383:691–3. 10.1056/NEJMc2015630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020;63:390–1. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aghagoli G, Gallo Marin B, Soliman LB, et al. Cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients: risk factors, predictors, and complications: a review. J Card Surg 2020;35:1302–5. 10.1111/jocs.14538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra AK, Lal A, Sahu KK, et al. Cardiovascular factors predicting poor outcome in COVID-19 patients. Cardiovasc Pathol 2020;49:107246. 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basso C, Leone O, Rizzo S, et al. Pathological features of COVID-19-associated myocardial injury: a multicentre cardiovascular pathology study. Eur Heart J 2020;41:3827–35. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra AK, Lal A, Sahu KK, et al. Quantifying and reporting cardiac findings in imaging of COVID-19 patients. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2020;90. 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1394. [Epub ahead of print: 09 Nov 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tersalvi G, Vicenzi M, Calabretta D, et al. Elevated troponin in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: possible mechanisms. J Card Fail 2020;26:470–5. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He XW, Lai JS, Cheng J, et al. [Impact of complicated myocardial injury on the clinical outcome of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2020;48:456–60. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200228-00137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu L, Fei J, Xiang H. Influence factors of death risk among COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China: a hospital-based case-cohort study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J-W, Han T-W, Woodward M, et al. The impact of 2019 novel coronavirus on heart injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020;63:518–24. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;350:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, et al. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med 2018;23:60–3. 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson PR, Smith CT, Hutton JL, et al. Aggregate data meta-analysis with time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med 2002;21:3337–51. 10.1002/sim.1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berlin JA, Longnecker MP, Greenland S. Meta-Analysis of epidemiologic dose-response data. Epidemiology 1993;4:218–28. 10.1097/00001648-199305000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Pei H, Bulluck H, et al. Periprocedural elevated myocardial biomarkers and clinical outcomes following elective percutaneous coronary intervention: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis of 44,972 patients from 24 prospective studies. EuroIntervention 2020;15:1444–50. 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domanski MJ, Mahaffey K, Hasselblad V, et al. Association of myocardial enzyme elevation and survival following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA 2011;305:585–91. 10.1001/jama.2011.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2231–64. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozinski M, Krintus M, Kubica J, et al. High-Sensitivity cardiac troponin assays: from improved analytical performance to enhanced risk stratification. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2017;54:143–72. 10.1080/10408363.2017.1285268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:533–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hui H, Zhang Y, Yang X. Clinical and radiographic features of cardiac injury in patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiavone M, Gasperetti A, Mancone M, et al. Redefining the prognostic value of high-sensitivity troponin in COVID-19 patients: the importance of concomitant coronary artery disease. J Clin Med 2020;9. 10.3390/jcm9103263. [Epub ahead of print: 12 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho SW. Subclinical and tiny myocardial injury within upper reference limit of cardiac troponin should not be ignored after noncardiac surgery. Korean Circ J 2020;50:938–9. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park J, Hyeon CW, Lee SH, et al. Mildly elevated cardiac troponin below the 99th-Percentile upper reference limit after noncardiac surgery. Korean Circ J 2020;50:925–37. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J, Hyeon CW, Lee S-H, et al. Preoperative cardiac troponin below the 99th-percentile upper reference limit and 30-day mortality after noncardiac surgery. Sci Rep 2020;10:17007. 10.1038/s41598-020-72853-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullins KE, Christenson RH. Optimal detection of acute myocardial injury and infarction with cardiac troponin: beyond the 99th Percentile, into the high-sensitivity era. Curr Cardiol Rep 2020;22:101. 10.1007/s11886-020-01350-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.