Abstract

Objective

The diagnosis of COVID-19 is based on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory secretions, blood, or stool. Currently, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most commonly used method to test for SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort analysis, we evaluated whether machine learning could exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection using routinely available laboratory values. A Random Forests algorithm with 1353 unique features was trained to predict the RT-PCR results.

Results

Out of 12,848 patients undergoing SARS-CoV-2 testing, routine blood tests were simultaneously performed in 1528 patients. The machine learning model could predict SARS-CoV-2 test results with an accuracy of 86% and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90.

Conclusion

Machine learning methods can reliably predict a negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test result using standard blood tests.

The diagnosis of COVID-19 is based on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory secretions, blood, or stool.1,2 Currently, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most commonly used method to test for SARS-CoV-2.3 Key limitations of this technique are its restricted availability and time requirement, often leaving clinicians unaware of the patient’s virus status for 12 hours or longer.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective cohort analysis, we evaluated whether machine learning could exclude SARS-CoV-2 PCR infection using routinely available laboratory values. Therefore, we extracted demographic, clinical, and laboratory data and concurrent (ie, within a 24-hour window) SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test results (Cobas SARS-CoV-2, Roche, Freiburg, Germany and Real-Time PCR Assay, BioProducts Genesig, Camberley, United Kingdom) from the electronic charts of patients in whom a SARS-CoV-2 test was performed at the Kepler University Hospital in Linz, Austria, from March 1, 2020, until April 30, 2020. Laboratory results used were from within 24 hours of admission. We trained a machine learning model (the Random Forests algorithm)4 using R version 3.6.35 and the packages RandomForest 4.6–14, Boruta 7.0.0, Psych 2.0.9, pROC 1.16.2, ROCR 1.0–11, Amelia 1.7.6, and Caret 6.0–866, ranger 0.12.1 using laboratory data with 1353 unique features of which 28 were used in the final model. The following standard laboratory values were included: blood count, electrolytes, C-reactive protein, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, liver enzymes, bilirubin, cholinesterase, and prothrombin time.

Thereafter, the dataset underwent extensive data preprocessing and data cleaning. The data cleaning included detection of typos and out-of-range values and the imputation of missing values; features with more than 25% of missing values were excluded. The remaining missing values were imputed using Strawman imputation, which replaces missing data by median values (continuous variables) or the most frequently occurring value (categorical values). The Strawman imputation method yielded results comparable to other, more complicated methods (eg, the “missForest” technique7). Censored numerical data were truncated (eg, “<0.1” was replaced by 0.1). Categorical features with >2 values were one-hot encoded (ie, a binary encoding for every category). Ordinal features were encoded as positive integers. Binary and numerical features were included as they were.

For the determination of our model performance, we conducted nested cross-validation. The hyperparameter search was conducted in the inner five-fold cross-validation loop via grid-search. The model performance is estimated in the outer loop in five folds. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Upper Austria (No. 1104/2020).

Results

Out of 12,848 patients undergoing SARS-CoV-2 testing, routine blood tests were performed concurrently in 1528 patients who were then included in the statistical analysis (Table 1). Of the 1528 study participants, 65 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. After data cleaning 1357 study participants were analyzed.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Routine Blood Results

| Variable | All Patients Mean (SD) | SARS-CoV-2 Test Negative Mean (SD) | SARS-CoV-2 Test Positive Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1528 | 1463 | 65 |

| Age (y) | 56.3 (26.6) | 55.9 (26.7) | 64 (21) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 50.1 | 50.1 | 44.6 |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 19.5 | 19.3 | 23.1 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.0 (2.3) | 13.0 (2.3) | 13.1 (2.2) |

| Hct (% red blood cells in whole blood) | 38 (7) | 38 (7) | 38 (6) |

| MCH (pg/cell) | 29.7 (2.7) | 29.7 (2.7) | 30.2 (2.5) |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33.8 (1.4) | 33.7 (1.4) | 34.5 (1.4) |

| MCV (fL) | 88.1 (6.9) | 88.1 (2.7) | 87.5 (6.1) |

| MPV (fL) | 9.8 (1.5) | 9.8 (1.5) | 10.3 (1.4) |

| RDW-CV (%) | 14.1 (2.1) | 14.2 (2.1) | 13.6 (1.9) |

| Erythrocytes (1012/L) | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| Normoblasts (cells/L) | 0.0 (0.6) | 0 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| White blood cell count (109/L) | 10.0 (7.3) | 10.1 (7.4) | 6.7 (5.1) |

| Platelets (109/μL) | 255 (96) | 258 (95) | 200 (106) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137 (5) | 137 (5) | 134 (5) |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 101 (5) | 101 (5) | 98 (6) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.4) |

| Total calcium (mmol/L) | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| GFR (mL/min) | 70 (27) | 70 (27) | 70 (24) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 20 (17) | 21 (17) | 20 (16) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.7) |

| ALT (U/L) | 39 (119) | 40 (122) | 28 (17) |

| gGT (U/L) | 74 (183) | 75 (186) | 53 (59) |

| LDH (U/L) | 264 (188) | 262 (190) | 304 (137) |

| Cholinesterase (kU/L) | 6.7 (2.3) | 6.8 (2.3) | 6.2 (2.3) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 106 (132) | 108 (134) | 78 (39) |

| Prothrombin time (%)a | 84 (25) | 84 (26) | 86 (22) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; gGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MPV, mean platelet volume; RDW-CV, red blood cell distribution width; SD, standard deviation.

SI conversion factors: To convert Hb or MCHC to g/L, multiply values by 10, Hct % × 0.01 → Proportion of 1.0, creatinine mg/dL × 88.4 → µmol/L, GFR mL/min × 60 → mL/s, BUN mg/dL × 0.357 → mmol/L, total bilirubin mg/dL × 17.104 → µmol/L, ALAT, gGT, LDH, alk. Phosphatase U/L × 0.0167 → µkat/L.

Data are given as mean values ± SD, if not otherwise indicated.

aNormal range 78%–123% for our laboratory.

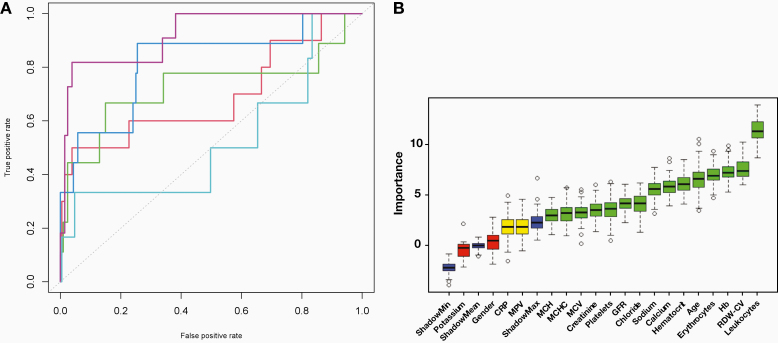

As calculated from the confusion matrix (Table 2), the machine learning model was able to detect SARS-CoV-2 test results with an accuracy of 81%, an area under the ROC curve of 0.74 (Figure 1A), a sensitivity of 60%, and a specificity of 82%. The positive and negative predictive values were 13% and 98%, respectively (F1 score = 0.21). The importance of single features for the model is displayed in Figure 1B.

Table 2.

Confusion Matrix for Model Results

| Confusion Matrix | Actual Positive | Actual Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Predicted positive (%) | 34 (6.8 ± 3.2) | 232 (46.4 ± 9.6) |

| Predicted negative (%) | 20 (4 ± 0.7) | 1071 (214.2 ± 9.1) |

| Accuracy: 86.1% (%) | PPV: 20.0 | NPV: 98.8 |

NPV, negative predicted value; PPV, positive predicted value.

First number: All folds; parentheses: mean and standard variance per fold.

Figure 1.

Machine learning model results. A, ROC, AUC (SD): 0.898 (0.002); every fold displayed in individual color. B, Relative feature importance of Random Forests algorithm obtained from the Boruta package of R.5 ShadowMin, shadowMax, and shadowMean refer to features created by the Boruta algorithm2,3 by shuffling the original features’ values (so-called shadow features) and training a model for prediction on the combined original and shuffled feature values; using this model, the Z-scores for the shadow features’ importances are calculated. Those features that are ranked more important than their shadow counterpart are marked as important. The Boruta algorithm is used as a validation method for feature importances calculated by the Random Forest algorithm. Blue boxplots are minimal, average, and maximum Z-scores of shadow features; red, yellow, and green boxplots are features that were rejected, remain tentatively important, and are confirmed important, respectively. Box upper and lower horizontal edges are first and third quartiles, whiskers denote the 1.5 interquartile range of feature importance, and circles are outliers. AUC, area under the curve; CRP, C-reactive protein; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; Hb, hemoglobin; RDW-CV, red blood cell distribution width; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Our results suggest that machine learning methods can predict SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results using routine blood values with fair accuracy. Although from a bedside perspective the value of such a model to predict a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result was poor, the high negative predictive value of 99% allows clinicians to reliably predict a negative SARS-CoV-2 test result with acceptable safety. The machine learning algorithm used, Random Forests, although not new, is a proven and effective method.

When evaluating the feature importance reported by the machine learning models, leukocyte count ranked as the most important feature. Elevated white blood cell counts have been observed early on in COVID-19 and have been linked to inflammation, similar to an increase in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.8 Another highly ranked feature, hemoglobin level, has been associated with mortality from COVID-19.9 Serum calcium changes are considered to be important for various functions of viruses such as structure and gene expression and release, along with promoting inflammation pathways linked to lung cell damage and edema formation.10,11

Our results may have relevant clinical implications, particularly for settings where SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing is not readily available and/or personal protection equipment is in short supply.

Although World Health Organization (WHO) considerations have defined acceptable and desirable price ranges for large-volume SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing, demand vs general availability and currently reported current prices commonly exceed these recommendations by a factor of 10 or higher.12,13 On the contrary, commonly reported reference costs of routinely ordered laboratory tests that were identified as features of high importance in our prediction model are well below the WHO-designated desirable range for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests.14 It can therefore be considered beneficial from an economic point of view to employ the presented model as support for clinical decision-making.

When interpreting the results of our analysis, 2 limitations must be considered. First, RT-PCR test results can be false-negative and false-positive.15 This potential impairs the validity of the model to predict true-negative RT-PCR results. Second, although 1357 study patients were included in our analysis, the sample size may still be considered low for machine learning methods, especially regarding the asymmetry of the classification problem. Inclusion of more patients may therefore have yielded more valid results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, machine learning methods can reliably predict a negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test result using standard blood values.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- WHO

World Health Organization

References

- 1. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR Eurosurveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):833–840. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Cheng MP, Papenburg J, Desjardins M, et al. Diagnostic testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus 2: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):726–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [computer program]. The R Foundation 2020. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

- 6. The Comprehensive R Archive Network [computer program]. The R Foundation. 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

- 7.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112–118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):762–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Sayad B, Afshar ZM, Mansouri F, Rahimi Z. Leukocytosis and alteration of hemoglobin level in patients with severe COVID-19: association of leukocytosis with mortality. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3(4):e194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Zhou Y, Frey TK, Yang JJ. Viral calciomics: interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium. 2009;46(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Cappellini F, Brivio R, Casati M, Cavallero A, Contro E, Brambilla P. Low levels of total and ionized calcium in blood of COVID-19 patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(9):e171–e173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ramdas K, Darzi A, Jain S. “Test, re-test, re-test”: using inaccurate tests to greatly increase the accuracy of COVID-19 testing. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):810–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. COVID-19 target product profiles for priority diagnostics to support response to the COVID-19 pandemic v.1.0. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-target-product-profiles-for-priority-diagnostics-to-support-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-v.0.1. Published September 28, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2020.

- 14. Estimated costs of 51 commonly ordered laboratory tests in Canada - PubMed [Internet] [cited 2020 September 26]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30615855/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Wikramaratna PS, Paton RS, Ghafari M, Lourenço J. Estimating the false-negative test probability of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Preprint. Posted online October 14, 2020. medRxiv https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20053355v3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]