To the Editor—The inability of the United States and most of Europe to replicate the successes observed across Asia in controlling the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 outbreak has led to spiralling infection rates, repeated lockdowns in Europe, and no sign of rounding the turn. In contrast, many Asian and Pacific countries are currently enjoying a semblance of normality. The study by Lewis et al [1] points to one of the causes for these differences.

They find the household secondary attack rate (HSAR) to be around 30% in Utah and Wisconsin in the United States, through the monitoring of household contacts of cases. This echoes another recent paper by Grijalva et al [2] for households in Wisconsin and Tennessee, who estimate the HSAR to be 30% to 50%, depending on whether those infected on enrollment are included in the definition.

In contrast, large household studies in China and Singapore found household attack rates to be less than one-half of their American counterparts: Ng et al [3] showed an HSAR of around 12% in Singapore, whereas Bi et al [4] estimated it to be 11% in Shenzhen. The difference is not attributable to underascertainment, as Ng et al confirmed infection status through serology.

We believe that a fundamental difference in case management lies behind these differences. In Singapore, all coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases, regardless of severity, are isolated in a healthcare facility upon diagnosis, either at a hospital or a converted community facility akin to China’s fangcang hospitals [5], until they are no longer infectious. No cases are isolated at home. Cases are managed similarly in China.

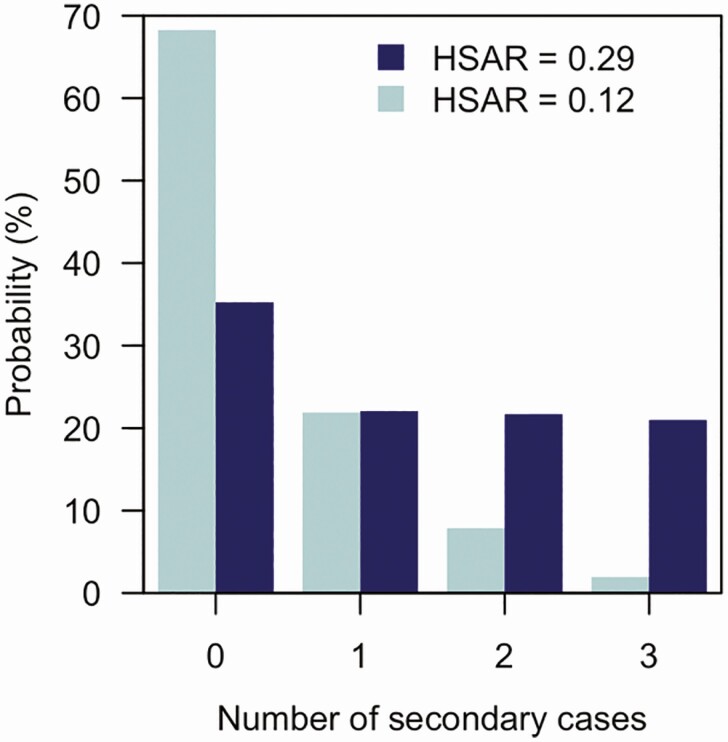

We previously argued on theoretical grounds [6] that isolation—not self-isolation—of cases may reduce the reproduction number sufficiently to reduce the size of outbreaks. Chain-binomial models (Figure 1) show that reduced HSAR leads to remarkable reductions in secondary household cases—an HSAR of 30% creates an estimated 1.3 secondary infections, whereas 12% creates just 0.4. Given the need to reduce transmission to less than 1 secondary case per index case for epidemic control, otherwise described as an effective R0 of below 1, this difference may explain why the epidemic continues to run amok in the United States.

Figure 1.

Number of additional infections in households of 4 members with a single index case, when the household secondary attack rate (HSAR) is 0.29 (based on Lewis et al [1]) or 0.12 (based on Ng et al [3]). Probabilities are from a chain-binomial model [7]. The average number of secondary cases in the HSAR = 0.29 case is 1.3; for HSAR = 0.12, it is 0.4.

For infection control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitals, it is established that colonized cases (ie, those without disease and at low risk of complications) should be cohorted to prevent onward transmission, which protects potentially vulnerable inpatients. This principle is not to benefit colonized patients, who may never develop disease, but those around them. Using the same principle, mild COVID-19 cases ought to be moved out of the household until they no longer pose a threat of transmitting infection.

If a country does not follow fundamental infection control principles in the COVID-19 pandemic, it is scarcely a surprise if it fails to control infection.

Notes

Financial support. B. L. D. and A. R. C. were supported by funding from Singapore’s National Medical Research Council through grants COVID19RF-004 and NMRC/CG/C026/2017_NUHS.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Lewis NM, Chu VT, Ye D, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grijalva CG, Rolfes MA, Zhu Y, et al. Transmission of SARS-COV-2 infections in households—Tennessee and Wisconsin, April-September 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Koh V, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and transmission risk factors among high-risk close contacts: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30833-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:911–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fang D, Pan S, Li Z, et al. Large-scale public venues as medical emergency sites in disasters: lessons from COVID-19 and the use of Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, China. BMJ Glob Health 2020; 5. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dickens BL, Koo JR, Wilder-Smith A, Cook AR. Institutional, not home-based, isolation could contain the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 2020; 395:1541–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bailey NTJ. The use of chain-binomials with a variable chance of infection for the analysis of intra-household epidemics. Biometrika 1953; 40:279–86. [Google Scholar]