Abstract

Background

Risk of reinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is unknown. We assessed the risk and incidence rate of documented SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in a cohort of laboratory-confirmed cases in Qatar.

Methods

All SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-confirmed cases with at least 1 polymerase chain reaction–positive swab that was ≥45 days after a first positive swab were individually investigated for evidence of reinfection. Viral genome sequencing of the paired first positive and reinfection viral specimens was conducted to confirm reinfection.

Results

Out of 133 266 laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, 243 persons (0.18%) had at least 1 subsequent positive swab ≥45 days after the first positive swab. Of these, 54 cases (22.2%) had strong or good evidence for reinfection. Median time between the first swab and reinfection swab was 64.5 days (range, 45–129). Twenty-three of the 54 cases (42.6%) were diagnosed at a health facility, suggesting presence of symptoms, while 31 (57.4%) were identified incidentally through random testing campaigns/surveys or contact tracing. Only 1 person was hospitalized at the time of reinfection but was discharged the next day. No deaths were recorded. Viral genome sequencing confirmed 4 reinfections of 12 cases with available genetic evidence. Reinfection risk was estimated at 0.02% (95% confidence interval [CI], .01%–.02%), and reinfection incidence rate was 0.36 (95% CI, .28–.47) per 10 000 person-weeks.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection can occur but is a rare phenomenon suggestive of protective immunity against reinfection that lasts for at least a few months post primary infection.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, epidemiology, reinfection, immunity, genetics

In a cohort of 133 266 laboratory-confirmed cases, the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reinfection was 0.02%, and the incidence rate of reinfection was 0.36 per 10 000 person-weeks. Reinfection rarely occurs, indicating protective immunity for at least a few months post primary infection.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been spreading around the globe, causing severe disruptions to social and economic activities [1–3]. Qatar, a peninsula in the Arabian Gulf region with a diverse population of 2.8 million [4, 5], has experienced a large epidemic with one of the highest laboratory-confirmed rates of infection at >60 000 infections per million population [6–8]. Antibody testing and mathematical modeling indicated that about half of the population has already been infected [6, 8–12].

The intensity of the epidemic with a high risk of reexposure to the infection, as well as the availability of a centralized data-capture system of all laboratory-confirmed infections, provided an opportunity to epidemiologically assess the presence and incidence of reinfection. This is a poorly understood feature of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology, and its elucidation is critical to inform global response, timing and intensity of future cycles, and impact and durability of potential vaccines [13–16].

Our aim was to assess the risk and incidence rate of documented reinfection in a cohort of 133 266 SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-confirmed infected persons. Since the relevant underlying question is whether risk of reinfection is appreciable or not, we implemented a conservative epidemiological approach for assessing documented reinfections that is prone to overestimate rather than underestimate risk of reinfection. However, we also conducted sensitivity analyses, implementing more stringent criteria for assessing reinfection. We further performed viral genome sequencing to confirm the reinfections.

METHODS

Sources of Data

We analyzed the centralized and standardized national SARS-CoV-2 testing and hospitalization database compiled at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), the main public healthcare provider and nationally designated provider for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) healthcare needs. The database covers all SARS-CoV-2 cases in Qatar and encompasses data on all polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing conducted from 28 February 2020–12 August 2020, including testing of suspected SARS-CoV-2 cases and traced contacts and infection surveillance testing. The database further includes data on hospital admission of COVID-19 patients and the World Health Organization (WHO) severity classification for each infection [17], which is assessed through individual chart reviews by trained medical personnel. Recently, data on serological testing for antibody on residual blood specimens collected for routine clinical care from attendees at HMC were also incorporated [6, 10].

Laboratory Methods

All PCR testing was conducted at HMC Central Laboratory or at Sidra Medicine Laboratory following standardized protocols. Nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs (Huachenyang Technology, China) were collected and placed in universal transport medium (UTM). Aliquots of UTM were extracted on the QIAsymphony platform (QIAGEN, Germantown, Maryland, USA) and tested with real-time reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using the TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit (100% sensitivity and specificity [18]; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachussets, USA) on ABI 7500 FAST (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachussets, USA), extracted using a custom protocol [19] on Hamilton Microlab STAR (Hamilton, Reno, Nevada, USA) and tested using AccuPower SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR Kit (100% sensitivity and specificity [20]; Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) on ABI 7500 FAST or loaded directly to the Roche Cobas 6800 system and assayed with the Cobas SARS-CoV-2 test (95% sensitivity, 100% specificity [21]; Roche Basel, Switzerland). The first assay targets the virus’s S, N, and ORF1ab regions, the second targets the virus’s RdRp and E gene regions, and the third targets the ORF1ab and E gene regions.

Serological testing was performed using the Roche Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 (99.5% sensitivity [22], 99.8% specificity [22, 23]; Roche, Switzerland), an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay that uses a recombinant protein that represents the nucleocapsid (N) antigen for determination of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Qualitative anti–SARS-CoV-2 results were generated following the manufacturer’s instructions (reactive: cutoff index for optical density ≥1.0 vs non-reactive: cutoff index <1.0).

Inclusion Criteria

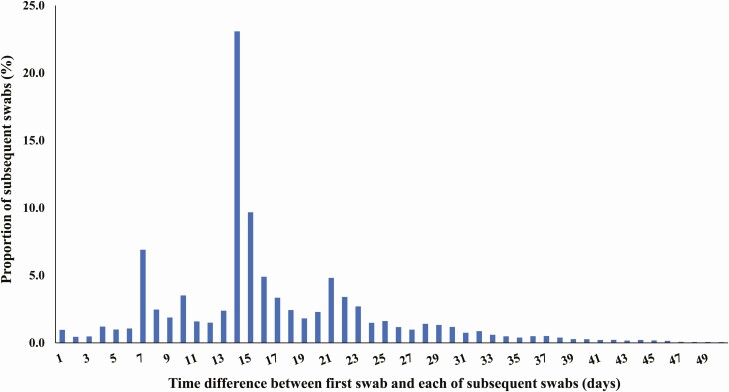

All SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-confirmed cases with at least 1 PCR-positive swab that was ≥45 days after a first positive swab were considered as suspected cases of reinfection. The 45-day cutoff was informed by data from observational cohorts of SARS-CoV-2–infected persons [24, 25] and was set to account for the duration of prolonged PCR positivity of several weeks in these patients. Cutoff determination was further informed by the distribution of the time difference between the first positive swab and subsequent positive swabs among SARS-CoV-2 cases with multiple swabs (Figure 1). The tail of this distribution indicates that a cutoff of 45 days (at the 99th percentile) provides an appropriate mark for defining the end of prolonged PCR positivity; a subsequent positive swab within 45 days of the first positive swab is likely to reflect prolonged PCR positivity (due to nonviable virus fragments) rather than reinfection and thus should not be included in analysis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the time difference between the first swab and subsequent swabs among all laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 cases with more than 1 positive swab. The cutoff of 45 days was at the 99th percentile and thus provides an appropriate mark for defining the end of the prolonged polymerase chain reaction positivity.

Suspected Reinfection Case Classification

Suspected cases of reinfection, that is, cases that fit the above-indicated inclusion criteria, were classified as showing strong evidence, good evidence, some evidence, or weak (or no) evidence for reinfection (Box 1). Classification was based on holistic quantitative and qualitative criteria applied to each investigated case. Criteria included the pattern and magnitude of the change in PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value across repeated swabs, time interval between subsequent swabs, PCR testing site (such as outpatients at primary care, hospital emergency, or inpatient hospitalization), purpose of PCR testing (such as appearance of symptoms, contact tracing, or survey/testing campaign), age, history of COVID-19–related hospital admission, and case severity per WHO classification [17].

Box 1. Classification of suspected cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reinfection based on the strength of supporting epidemiological evidence.

Suspected cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reinfection: all laboratory-confirmed cases with at least 1 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–positive swab that was ≥45 days after a first positive swab.

Strong evidence for reinfection: individuals having positive swabs with a PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value <30 at least 45 days after the first positive swab. No contextual evidence supporting poor control of first infection, such as age ≥70 years, repeated swabs on hospitalized patients, and severe or critical World Health Organization (WHO) disease classifications.

Good evidence for reinfection: individuals having positive swabs with a PCR Ct value ≥30 at least 45 days after the first positive swab, but where PCR positivity was associated with contextual evidence supporting the status of reinfection:

Appearance of symptoms (often as proxied by being diagnosed at a health facility)

Infection diagnosis through contact tracing (indicating recent exposure to an infected person)

Lower Ct value compared with last positive swab (indicating increasing viral load)

Irregular and spaced-out pattern for repeated swabbing (to exclude cases under clinical management that are indicative of poor control of first infection).

No contextual evidence supporting poor control of first infection, such as age ≥70 years, repeated swabs on hospitalized patients, and severe or critical WHO disease classifications.

Some evidence for reinfection: individuals having positive swabs with a PCR Ct value ≥30 at least 45 days after the first positive swab but typically bordering the cutoff of 45 days. PCR positivity was not associated with evidence supporting the status of reinfection (listed above).

Weak evidence for reinfection: individuals having swabs with a PCR Ct value ≥30 at least 45 days after the first positive swab but typically bordering the cutoff of 45 days. PCR positivity was associated with contextual evidence indicative of poor infection control of the first infection rather than reinfection (such as age ≥70 years, repeated swabs on hospitalized patients, and severe or critical WHO disease classifications).

Overall, swabs with Ct <30 (suggestive of recent active infection) at least 45 days after the first positive swab were considered as showing strong evidence for reinfection. Swabs with Ct ≥30 at least 45 days after the first positive swab were considered as showing good evidence for reinfection if PCR positivity was associated with contextual evidence that supported the status of “reinfection,” including appearance of symptoms (often as proxied by being diagnosed at a health facility), if the infection was diagnosed through contact tracing (indicating recent exposure to an infected person), if the change in Ct value from the last swab was to a lower Ct value (indicating increasing viral load), and/or if the repeated swabbing did not follow a regular pattern and the time interval between repeated swabs was not short (to exclude cases under clinical management that are indicative of poor control of first infection).

Shorter durations bordering the 45-day cutoff with Ct values ≥30 and no contextual evidence supporting the status of reinfection were indicative of some evidence for reinfection but not strong or good evidence for reinfection as they are more likely to reflect the long tail of the prolonged PCR positivity distribution (Figure 1) [24, 25]. Age ≥70 years, repeated swabs on hospitalized patients, and severe or critical WHO disease classifications were considered as contextual factors indicative of poor control of the first infection rather than reinfection. Cases that had such contextual factors (and implicitly did not fit the criteria of strong, good, or some evidence for reinfection) were considered to have weak (or no) evidence for reinfection.

Of note is that hospitalized COVID-19 cases often had multiple subsequent swabs administered as part of clinical care. Repeated swabbing was standard earlier in the epidemic, as the criteria for discharge from an isolation facility required at least 2 subsequent PCR-negative swabs. This was changed later to a time-based criteria per updated WHO recommendation [26].

Reinfection Risk and Rate

Documented reinfection risk was assessed by quantifying the proportion of cases with strong or good evidence for reinfection out of all laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases that were diagnosed ≥45 days from end-of-study censoring. The incidence rate of documented reinfection was calculated by dividing the number of cases with strong or good evidence by the number of person-weeks contributed by all laboratory-confirmed cases who had their first positive swab ≥45 days before the day of analysis. The follow-up person-time was calculated starting from 45 days after the first positive swab and up to the reinfection swab, all-cause death, or end-of-study censoring.

Sensitivity Analyses

Since we implemented a conservative approach that is prone to overestimate risk of documented reinfection, several sensitivity analyses were conducted to implement more stringent criteria for assessing reinfection. This included excluding cases where the Ct value for the first and/or subsequent positive swab was unknown or with a value ≥35 (to exclude potential PCR false-positive cases), changing the ≥45-day cutoff to a ≥60-day cutoff to further exclude potential cases of long-term prolonged PCR positivity, and (most stringent) setting the definition of recent active infection at a Ct cutoff value of <25 (instead of <30) and excluding any suspected reinfection case with Ct >25.

Viral Genome Sequencing and Analysis

Viral genome sequencing was conducted on retrieved paired samples of the first positive swab and reinfection swab for patients with strong or good evidence for reinfection as confirmatory analysis. Further details about the viral genome sequencing methods can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Ethical Approval

The HMC and Weill Cornell Medicine–Qatar institutional review boards approved the study.

RESULTS

Epidemiological Analysis

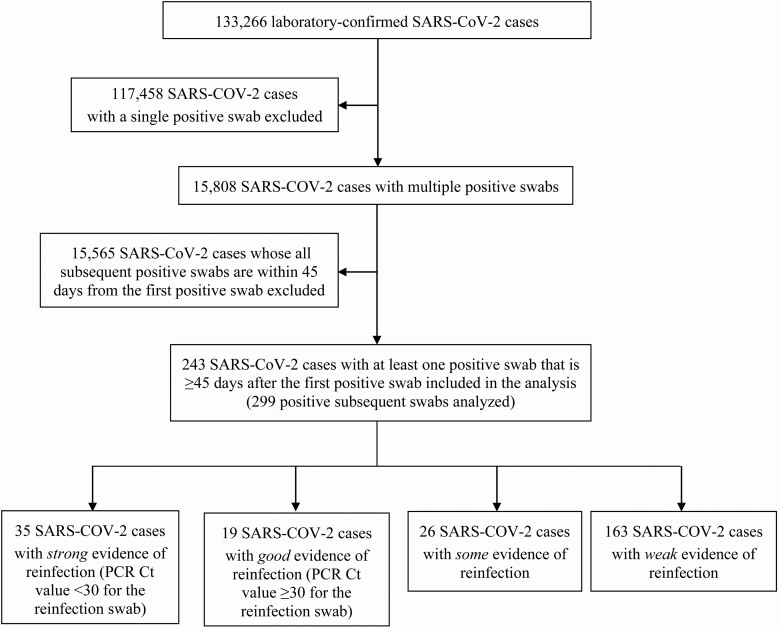

Figure 2 illustrates the selection process of SARS-CoV-2 eligible cases and summarizes the results of their reinfection status evaluation. Of 133 266 laboratory-confirmed cases, 117 458 had only a single positive swab and thus were excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 15 808 cases with multiple swabs, only 243 persons had at least 1 subsequent positive swab that was ≥45 days from the first positive swab and thus qualified for inclusion in analysis.

Figure 2.

Flow chart describing the selection process of SARS-CoV-2 eligible cases and summarizing the results of their reinfection status evaluation. Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

There were 299 positive swabs collected ≥45 days after the first positive swab for these 243 persons. Individual investigation of each of these swabs yielded 54 cases with strong or good evidence for reinfection. Of these, 35 had strong evidence for reinfection (Ct <30), while the remaining 19 had good evidence for reinfection (Ct ≥30). An additional 26 cases showed some evidence for reinfection, while evidence was weak for the remaining 163 cases.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 54 cases classified as showing strong or good evidence for reinfection. Almost all cases were males, but this reflects the focus of the epidemic in craft and manual workers [6]. Median age was 33 years (range, 16–57), and median time between the first swab and the reinfection swab was 64.5 days (range, 45–129). Median Ct value was 28 (range, 14–37); it was 22 (range, 14–29) for the 35 swabs classified with strong evidence (Ct <30) and 32 (range, 30–37) for the remaining swabs (Ct ≥30). Twenty-three cases (42.6%) were diagnosed at a health facility, suggesting presence of symptoms, while 31 (57.4%) were identified incidentally either through random testing campaigns/surveys (n = 15; 27.8%) or contact tracing (n = 16; 29.6%), suggesting minimal symptoms, if any.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Individuals Classified as Showing Strong or Good Evidence for Reinfection

| Sociodemographic | PCR Testing | Hospitalization | Ab Testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Sex | Age Group (years) | Sample Type | PCR Swab Date | Positive Swab Type | Average Cycle Threshold Value | Case Severitya | Hospital Admissionb | Length of Stay (days) | Ab Test Date | Ab Status |

| Strong evidence for reinfection | |||||||||||

| 1 | Male | 50–54 | Surveyc | 14 May | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 50–54 | Surveyc | 23 July | Reinfection swab | 14 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 26 July | Negative | |

| 2 | Male | 30–34 | Health facility | 16 June | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Health facility | 10 August | Reinfection swab | 16 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 3 | Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 2 April | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | 7 April | 1 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 26 June | Reinfection swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 27 June | Negative | |

| 4 | Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 30 April | First positive swab | 33 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 15 July | Reinfection swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 5 | Male | 35–39 | Contact tracing | 31 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 20 April | Subsequent positive swab | 24 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 7 August | Reinfection swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 6 | Female | 50–54 | Contact tracing | 4 June | First positive swab | 34 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 50–54 | Health facility | 27 July | Reinfection swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 14 July | Negative | |

| 7 | Female | 20–24 | Health facility | 26 April | First positive swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 20–24 | Health facility | 19 July | Reinfection swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 8 | Male | 30–34 | Health facility | 5 June | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 4 August | Reinfection swab | 18 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 9 | Male | 20–24 | Contact tracing | 3 April | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 9 July | Reinfection swab | 18 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 10 | Female | 20–24 | Health facility | 24 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 20–24 | Contact tracing | 23 June | Reinfection swab | 19 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 11 | Male | 35–39 | Contact tracing | 30 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Contact tracing | 24 June | Reinfection swab | 19 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 19 July | Positive | |

| 12 | Female | 45–49 | Health facility | 28 May | First positive swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 45–49 | Health facility | 10 August | Reinfection swab | 20 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 4 June | Negative | |

| 13 | Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 3 April | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | 6–7 April | 1 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 15 July | Reinfection swab | 20 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 14 | Female | 40–44 | Contact tracing | 12 June | First positive swab | 24 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 40–44 | Health facility | 8 August | Reinfection swab | 21 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 3 July | Positive | |

| 15 | Male | 50–54 | Contact tracing | 22 April | First positive swab | 34 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 50–54 | Contact tracing | 23 July | Reinfection swab | 21 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 22 July | Negative | |

| 16 | Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 9 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | 9–14 Marchb | 5 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Contact tracing | 21 May | Reinfection swab | 21 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 17 | Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 15 May | First positive swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 12 August | Reinfection swab | 22 | Not assessedd | 13 August | 1 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 18 | Female | 20–24 | Health facility | 23 May | First positive swab | 33 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 20–24 | Health facility | 7 August | Reinfection swab | 22 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 2 August | Negative | |

| 19 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 3 June | First positive swab | 23 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 7 August | Reinfection swab | 23 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 13 July | Positive | |

| 20 | Female | 45–49 | Health facility | 2 May | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Female | 45–49 | Health facility | 29 July | Reinfection swab | 25 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 30 July | Negative | |

| 21 | Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 12 May | First positive swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 27 July | Reinfection swab | 25 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 28 July | Positive | |

| 22 | Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 31 May | First positive swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 5 August | Reinfection swab | 26 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 23 | Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 16 June | First positive swab | 31 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Contact tracing | 11 August | Reinfection swab | 27 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 24 | Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 8 June | First positive swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 3 August | Reinfection swab | 27 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 25 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 28 May | First positive swab | 21 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Contact tracing | 30 July | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 26 | Male | 40–44 | Surveyc | 22 April | First positive swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 6 May | Subs positive swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 14 May | Subsequent positive swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 40–44 | Surveyc | 12 June | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 27 | Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 25 April | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 10 June | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 28 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 11 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Contact tracing | 8 June | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 10 July | Positive | |

| 29 | Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 12 May | First positive swab | 21 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 30 June | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 30 | Male | 15–19 | Health facility | 5 June | First positive swab | 20 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 15–19 | Health facility | 8 August | Reinfection swab | 28 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 31 | Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 25 April | First positive swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Surveyc | 22 June | Reinfection swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 32 | Male | 35–39 | Surveyc | 12 May | First positive swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Surveyc | 30 June | Reinfection swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 33 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 26 April | First positive swab | 17 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 6 July | Reinfection swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 34 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 11 May | First positive swab | 33 | Not assessedd | 14 May | 1 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Contact tracing | 28 July | Reinfection swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 35 | Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 17 May | First positive swab | 25 | Not assessedd | 31 May-1 June | 2 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 20 July | Reinfection swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 26 July | Positive | |

| Good evidence for reinfection | |||||||||||

| 36 | Male | 30–34 | Health facility | 30 April | First positive swab | 22 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 26 June | Reinfection swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 37 | Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 4 May | First positive swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 11 July | Reinfection swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 38 | Male | 25–29 | Health facility | 2 June | First positive swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Contact tracing | 4 August | Reinfection swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 39 | Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 6 May | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 10 May | Subsequent positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 20 May | Subsequent positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 30 June | Reinfection swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 40 | Male | 55–59 | Health facility | 10 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Mild | 14–20 Marchb | 7 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 55–59 | Health facility | 3 June | Reinfection swab | 31 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 22 July | Positive | |

| 41 | Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 23 April | First positive swab | 26 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Health facility | 7 May | Subsequent positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 12 June | Reinfection swab | 31 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 42 | Male | 15–19 | Health facility | 10 April | First positive swab | 33 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 15–19 | Health facility | 26 May | Reinfection swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 43 | Male | 15–19 | Health facility | 9 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | 16–23 Marchb | 8 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 15–19 | Contact tracing | 26 May | Reinfection swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 44 | Male | 25–29 | Surveyc | 26 April | First positive swab | 30 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Surveyc | 16 May | Subsequent positive swab | 34 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 25–29 | Surveyc | 20 June | Reinfection swab | 32 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 45 | Male | 25–29 | Contact tracing | 26 April | First positive swab | 29 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 25–29 | Contact tracing | 23 June | Reinfection swab | 33 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 46 | Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 23 April | First positive swab | 20 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Contact tracing | 20 June | Reinfection swab | 34 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 47 | Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 29 April | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 20 June | Reinfection swab | 34 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 48 | Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 8 April | First positive swab | 20 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 35–39 | Health facility | 16 June | Reinfection swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 49 | Male | 40–44 | Surveyc | 6 April | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 40–44 | Health facility | 4 June | Reinfection swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 50 | Male | 50–54 | Contact tracing | 20 April | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 50–54 | Contact tracing | 11 June | Reinfection swab | 35 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 51 | Male | 45–49 | Health facility | 21 April | First positive swab | 37 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 45–49 | Surveyc | 19 June | Reinfection swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | 2 August | Positive | |

| 52 | Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 29 March | First positive swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Surveyc | 15 June | Reinfection swab | 37 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 53 | Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 20 April | First positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 30–34 | Contact tracing | 4 June | Reinfection swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

| 54 | Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 11 April | First positive swab | 27 | Not assessedd | 14–30 Aprilb | 17 | Not tested | Unknown |

| Male | 20–24 | Health facility | 26 April | Subsequent positive swab | 36 | Not assessedd | Inpatient | -- | Not tested | Unknown | |

| Male | 20–24 | Surveyc | 24 June | Reinfection swab | Unknown | Not assessedd | Not hospitalized | 0 | Not tested | Unknown | |

Individuals with ID numbers 20, 27, 33, and 44 were confirmed as reinfection cases by viral genome sequencing.

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

aSeverity classification per World Health Organization guidelines was conducted only on a subset of all cases where it was deemed relevant. Asymptomatic cases or cases with minimal symptoms were not formally assessed for severity.

bIt has been common to use hospitalization as a form of isolation, especially early in the epidemic.

cThe category “survey” refers to surveillance testing campaigns conducted in workplaces and residential areas.

dNot assessed because of no or minimal symptoms to warrant clinical assessment.

Nine of the 54 cases that showed strong or good evidence for reinfection were hospitalized at any time. However, all but 1 occurred following the primary infection; only 1 hospitalization occurred at the time of reinfection, but the patient was discharged the next day. Most hospitalizations occurred for isolation or initial assessment purposes as cases had no or minimal symptoms. Only 1 case had sufficient symptoms to warrant an infection severity assessment (during primary infection) but was classified with “mild” severity per WHO classification. No deaths were recorded. Of note, the vast majority of infections in Qatar occurred in young, healthy men and were of low severity [6, 12].

Antibody test results were available for 48 of the 243 assessed individuals (Supplementary Table 1), of whom 30 (62.5%) had detectable antibodies. Of the 13 with strong evidence for reinfection and available antibody results, 7 (53.9%) were seronegative. Both individuals with good evidence for reinfection, 3 of the 4 individuals with some evidence for reinfection, and 19 of the 29 individuals with weak evidence for reinfection were seropositive.

Risk of documented reinfection was estimated at 0.05% (95% confidence interval [CI], .04%–.07%), that is, a total of 54 reinfections among 101 349 persons with laboratory-confirmed infection (the cohort of infected persons after excluding persons who were diagnosed within 45 days from end-of-study censoring). The incidence rate of reinfection was estimated at 1.09 (95% CI, .84–1.42) per 10 000 person-weeks, that is, a total of 54 reinfection events in a follow-up person-time of 495 208.7 person-weeks.

Results of sensitivity analyses can be found in Supplementary Table 2. In these analyses, the estimate for the risk of reinfection was between 0.02% (95% CI, .01–.03) and 0.03% (95% CI, .02–.04), while that for the incidence rate of reinfection was between 0.38 (95% CI, .24–.60) and 1.06 (95% CI, .75–1.50) per 10 000 person-weeks. Although these sensitivity analyses confirmed our results, they suggested overestimation of the already low risk of reinfection.

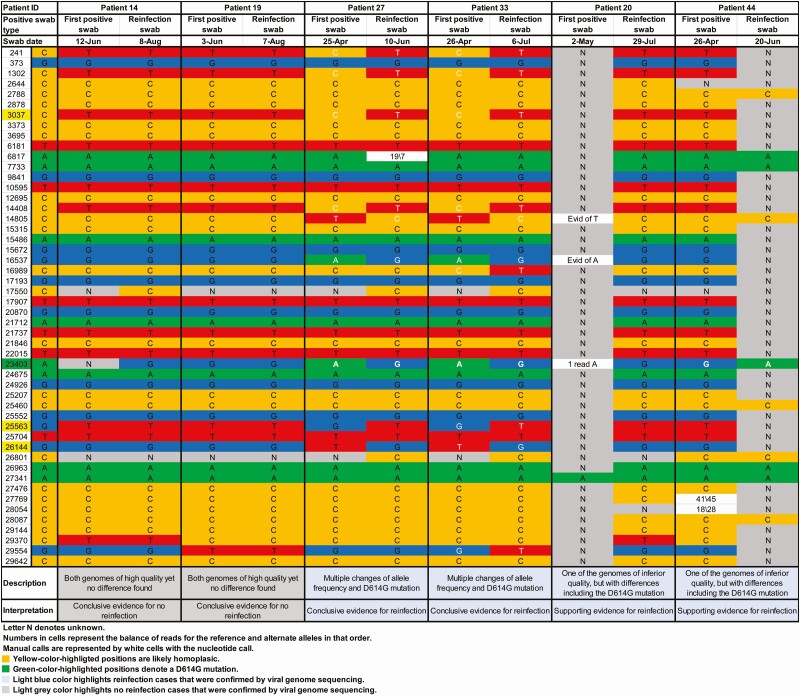

Confirmation of Reinfection Through Viral Genome Sequencing

Paired specimens of the first positive and reinfection swabs could be retrieved for 23 of the 54 cases with strong or good evidence for reinfection. Table 2 summarizes the viral genome sequencing results, and Figure 3 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 show the detailed analysis for each genome pair.

Table 2.

Results of Reinfection Confirmatory Analysis

| Viral Genome Sequencing Evidence for Reinfection | Indication Upon Comparing Each Genome Pair | N |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient evidence to warrant interpretation | One or 2 genomes of low quality | 11 |

| No evidence for reinfection | One change of allele frequency | 3 |

| Shifting balance of quasi-species with no evidence for reinfection | Several changes of allele frequency | 3 |

| Conclusive evidence for no reinfection | Both genomes of high quality yet no differences found | 2 |

| Supporting evidence for reinfection | One genome of inferior quality but with D614G mutation | 2 |

| Conclusive evidence for reinfection | Multiple changes of allele frequency and D614G mutation | 2 |

| Total | 23 |

Based on viral genome sequencing of the paired viral specimens of the first positive and reinfection swabs for 23 patients with strong or good epidemiological evidence for reinfection.

Figure 3.

Viral genome sequencing analysis of the paired viral specimens of the first positive and reinfection swabs for the 6 patients with conclusive or supporting evidence for reinfection or no reinfection.

There was insufficient evidence to warrant interpretation for 11 pairs because of low genome quality. For 6 pairs, there were 1 to several changes of allele frequency indicative, at best, of a shifting balance of quasi-species and thus no evidence for reinfection. For 2 pairs, remarkably, there was conclusive evidence for no reinfection as both genomes were of high quality yet no differences were found. For both patients, Ct was <25 for the first positive and reinfection swabs, indicating persistent active infection (Table 1). These 2 cases were also seropositive (Table 1).

For 2 pairs, there was conclusive evidence for reinfection with multiple changes of allele frequency and presence of the D614G mutation (23403bp A>G), which is a variant that appeared and expanded replacing the original D614 form [27, 28]. Although 1 of the genomes was of inferior quality, for 2 pairs there was sufficient evidence for differences, including the presence of the D614G mutation, thereby rendering evidence for reinfection. Three of these 4 cases with viral genome sequencing confirmation of reinfection were classified above (epidemiological criteria) as having strong evidence for reinfection, with the fourth classified as having good evidence (Table 1). The antibody test result was available for 1 case at the time of reinfection, and the individual was seronegative.

In summary, for the 12 cases where viral genome sequencing evidence was available, 4 cases were confirmed as reinfections, a confirmation rate of 33.3%. Applying this rate to the above-estimated reinfection metrics yielded a risk of documented reinfection of 0.02% (95% CI, .01%–.02%) and incidence rate of reinfection of 0.36 (95% CI, .28–.47) per 10 000 person-weeks.

DISCUSSION

Using several analyses and sensitivity analyses, our results indicate conclusive evidence for the presence of reinfections in the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Qatar, but the risk for documented reinfection was very rare, at about 2 reinfections per 10 000 infected persons. This finding is striking as the epidemic in Qatar has been intense, with half of the population estimated to have been infected [6, 8–12]. Considering the strength of the force of infection, estimated at a daily probability of infection exceeding 1% at the epidemic peak around 20 May 2020 [6], it is all but certain that a significant proportion of the population has been repeatedly exposed to the infection, but such reexposures did not lead to any documentable reinfections.

Indeed, of all epidemiologically identified reinfections, nearly two-thirds (57%) were discovered accidentally, either through random testing campaigns/surveys or through contact tracing. None were severe, critical, or fatal; all reinfections were asymptomatic or with minimal or mild symptoms. These findings may suggest that most infected persons develop immunity against reinfection that lasts for at least a few months and that reinfections (if they occur) are well tolerated and no more symptomatic than primary infections. Further follow-up of this cohort of infected persons over time may allow elucidation of potential effects of waning of immunity.

Other lines of evidence for this cohort also support this conclusion. Among 2559 PCR-positive persons where an antibody test outcome was available [6] and where the first positive PCR test was conducted >3 weeks before the serology test to accommodate for the delay in development of detectable antibodies following onset of infection [24, 25], 91.7% were antibody-positive [6]. The high antibody positivity was also stable for more than 3 months [6], as described elsewhere [14, 25]. The epidemic curve in Qatar was further characterized by rapid growth followed by rapid decline [6, 8, 12] at a time when levels of social and physical distancing restrictions were fairly stable. This points to susceptibles–infected–recovered (SIR) epidemic dynamics, with most infections eliciting immunity against reinfection.

This assessment has limitations. We assessed risk of only documented reinfections. Other reinfections could have occurred but went undocumented, perhaps because of minimal/mild or no symptoms. It is also possible that with the primed immune system following primary infection, reinfections could be milder and shorter [15]. A recent nationwide population-based survey in Qatar estimated that only 9.3% (95% CI, 7.9%–11.0%) of those who were antibody-positive had a prior documented laboratory-confirmed infection [9], suggesting that undocumented infections (or reinfections) could possibly be 10-fold higher than documented infections (or reinfections). This finding indicates that the incidence rate of both documented and undocumented reinfections may add up to approximately 10 per 10 000 person-weeks. A recent mathematical modeling study estimated the incidence rate of infection in Qatar at the time of the present study, including both documented and undocumented infections, at approximately 200 per 10 000 person-weeks [8]. Comparison of these incidence rates suggests that the “efficacy” of natural infection against reinfection is around .

Viral genome sequencing analysis was possible for only a subset of reinfections. Antibody testing outcomes were available for a small number of cases, limiting use and inferences of the link between antibody status and risk of reinfection. It is of note that for 1 of the genetically confirmed reinfections, the antibody test result was available but was seronegative (Table 1), as with the Hong Kong reinfected patient [29].

In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 reinfection appears to be a rare phenomenon. This may suggest that immunity develops after the primary infection and lasts for at least few months and that immunity may protect against reinfection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. L. J. A. conceived and codesigned the study and led the statistical analyses. H. C. codesigned the study, performed the data analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J. A. M. led the viral genome sequencing analyses, and A. A. A., Y. A. M., and S. Y. conducted these analyses. All authors contributed to data collection and acquisition, database development, discussion and interpretation of the results, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank Her Excellency Dr Hanan Al Kuwari, minister of Public Health, for her vision, guidance, leadership, and support. We also thank Dr Saad Al Kaabi, chair of the System Wide Incident Command and Control (SWICC) Committee for the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) national healthcare response, for his leadership, analytical insights, and instrumental role in enacting data information systems that made these studies possible. We further extend our appreciation to the SWICC Committee and the Scientific Reference and Research Taskforce members for their informative input, scientific technical advice, and enriching discussions. We also thank Dr Mariam Abdulmalik, CEO of the Primary Health Care Corporation and the chairperson of the Tactical Community Command Group on COVID-19, as well as members of this committee for providing support to the teams that worked on the field surveillance. We thank Dr Nahla Afifi, director of Qatar Biobank (QBB), Ms Tasneem Al-Hamad, Ms Eiman Al-Khayat, and the rest of the QBB team for their unwavering support in retrieving and analyzing samples and in compiling and generating databases for COVID-19 infection, as well as Dr Asmaa Al-Thani, chairperson of the Qatar Genome Programme Committee and board vice chairperson of QBB, for her leadership of this effort. We also acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the Clinical Coding Team and the COVID-19 Mortality Review Team, both at Hamad Medical Corporation, and the Surveillance Team at the Ministry of Public Health.

Disclaimer. The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Financial support. The authors are grateful for support provided by the Biomedical Research Program; the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core; and the Genomics Core, all at Weill Cornell Medicine–Qatar, as well as for support provided by the Ministry of Public Health and Hamad Medical Corporation.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed 14 March 2020.

- 2.De Walque D, Friedman J, Gatti RV, Mattoo A. How two tests can help contain COVID-19 and revive the economy. 2020. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/766471586360658318/pdf/How-Two-Tests-Can-Help-Contain-COVID-19-and-Revive-the-Economy.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2020.

- 3.Kaplan J, Frias L, McFall-Johnsen M. A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown. 2020. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/countries-on-lockdown-coronavirus-italy-2020–3. Accessed 25 April 2020.

- 4.Planning and Statistics Authority—State of Qatar. Qatar monthly statistics. 2020. Available at: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/pages/default.aspx. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- 5.Planning and Statistics Authority—State of Qatar. The simplified census of population, housing & establishments. 2019. Available at: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Population/Population/2018/Population_social_1_2018_AE.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- 6.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Characterizing the Qatar advanced-phase SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. medRxiv 2020:2020.07.16.20155317v2 (not peer-reviewed preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Kuwari HM, Abdul Rahim HF, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Epidemiological investigation of the first 5685 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar, 28 February-18 April 2020. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e040428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Seedat S, et al. Mathematical modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Qatar and its impact on the national response to COVID-19. medRxiv 2020:2020.11.08.20184663 (not peer-reviewed preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Thani MH, Farag E, Bertollini R, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the craft and manual worker population of Qatar. medRxiv 2020:2020.11.24.20237719 (not peer-reviewed preprint). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle P, Chemaitelly H, Al Kanaani Z, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the urban population of Qatar. under preparation.

- 11.Jeremijenko A, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Evidence for and level of herd immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection: the ten-community study. medRxiv 2020:2020.09.24.20200543 (not peer-reviewed preprint). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seedat S, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection hospitalization, severity, criticality, and fatality rates. medRxiv 2020:2020.11.29.20240416 (not peer-reviewed preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seow J, Graham C, Merrick B, et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol 2020; 5:1598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wajnberg A, Amanat F, Firpo A, et al. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science 2020; 370:1227–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellam P, Barclay W. The dynamics of humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection and the potential for reinfection. J Gen Virol 2020; 101:791–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makhoul M, Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, et al. Epidemiological impact of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: mathematical modeling analyses. Vaccines 2020; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-covid-19. Accessed 31 May 2020.

- 18.Thermo Fisher Scientific. TaqPath™ COVID‑19 CE‑IVD RT‑PCR Kit instructions for use. 2020. Available at: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0019215_TaqPathCOVID-19_CE-IVD_RT-PCR%20Kit_IFU.pdf. Accessed 2 December 2020.

- 19.Kalikiri MKR, Hasan MR, Mirza F, Xaba T, Tang P, Lorenz S. High-throughput extraction of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs using solid-phase reverse immobilization beads. medRxiv 2020:2020.04.08.20055731. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubina R, Dziedzic A. Molecular and serological tests for COVID-19, a comparative review of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus laboratory and point-of-care diagnostics. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration. Cobas® SARS-CoV-2: qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 systems. 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/136049/download. Accessed 2 December 2020.

- 22.Muench P, Jochum S, Wenderoth V, et al. Development and validation of the elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoassay as a highly specific tool for determining past exposure to SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche Group. Roche’s COVID-19 antibody test receives FDA emergency use authorization and is available in markets accepting the CE mark. 2020. Available at: https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2020-05-03.htm. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 24.Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA 2020; 323:2249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wajnberg A, Mansour M, Leven E, et al. Humoral response and PCR positivity in patients with COVID-19 in the New York City region, USA: an observational study. Lancet Microbe 2020; 1:e283–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Criteria for releasing COVID-19 patients from isolation. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/criteria-for-releasing-covid-19-patients-from-isolation. Accessed 1 July 2020.

- 27.Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell 2020; 182:812–27 e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grubaugh ND, Hanage WP, Rasmussen AL. Making sense of mutation: what D614G means for the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Cell 2020; 182:794–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.To KK, Hung IF, Ip JD, et al. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.