Abstract

The phylogenetic relationship between Ephemeroptera (mayflies) and Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) remains hotly debated in the insect evolution community. We sequenced the complete mitochondrial genome of Caenis sp. (Ephemeroptera: Caenidae) to discuss the phylogenetic relationship of Palaeoptera. The mitochondrial genome of Caenis sp. is a circular molecule of 15,254 bp in length containing 37 genes (13 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs, and 2 rRNAs), which showed the typical insect mitochondrial gene arrangement. In BI and ML phylogenetic trees using 71 species of 12 orders, our results support the Ephemeroptera as the basal group of winged insects.

Keywords: Ephemeroptera, Palaeoptera, Metapterygota, mitochondrial genome, phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationships among the Ephemeroptera (mayflies), Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and Neoptera has been hotly debated by researchers, often based on their use of different molecular methods (Zhang et al. 2008; Regier et al. 2010; Ishiwata et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2013). These researchers have proposed three main hypotheses, the Palaeoptera hypothesis ((Ephemeroptera + Odonata) + Neoptera) (Blanke et al. 2012), the basal Ephemeroptera hypothesis (Ephemeroptera + (Odonata + Neoptera)) (Zhang et al. 2008), and the basal Odonata hypothesis (Odonata + (Ephemeroptera + Neoptera)) (Li et al. 2014). Different hypotheses, using different datasets, genes or phylogenetic approaches, have received distinct support (Mallatt and Giribet 2006; Meusemann et al. 2010; Song et al. 2016). Compared to 42 families in Ephemeroptera, there are only 19 complete or nearly complete mitochondrial genomes of Ephemeroptera belonging to 11 families on Genbank (Tang et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2018). In this study, we sequenced the complete mitochondrial genome of another ephemeropteran species, Caenis sp. (MG910499), to provide more molecular data that enables researchers to further discuss three main hypotheses of the origin of winged insects.

The sample of Caenis sp. was collected in Tianmu Mountain (30°21′35′′ N, 119°26′12′′ E), China, identified by Dr. JY Zhang (College of Life Sciences and Chemistry, Zhejiang Normal University). Total genomic DNA was extracted from individual tissues of the sample using Ezup Column Animal Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Sangon Biotech Company, Shanghai, China). All mayfly samples and DNA samples were stored in the lab of Dr. JY Zhang. Universal primers were used to amplify some partial fragments as described in Zhang et al. (2008).

The complete mitochondrial genome of Caenis sp. was a typical circular DNA molecule of 15,254 bp in length containing 37 genes (13 protein-coding genes [PCGs]), 22 tRNAs, and two rRNAs) and an A + T region. The AT content of the whole genome was 68.4% and the length of the control region was 527 bp with 71.6% AT content.

The phylogenetic relationship was constructed from the 13 PCGs by following the Bayesian Inference (BI) and Phylip Maximum Likelihood (PhyML) methods and using MrBayes version 3.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012) and PhyML version 3.0 (Guindon and Gascuel 2003), respectively. The 13 PCGs from the mitochondrial genomes of 71 species, which included 20 Ephemeroptera species, 27 Odonata species, 16 Neoptera species, 5 Archaeognatha species, and 3 Zygentoma species, were used to investigate the phylogenetic relationships. Among them, Archaeognatha and Zygentoma were used as outgroups. To select conserved regions of the nucleotide, each alignment was performed by Gblock 0.91b (Castresana 2000) using default settings.

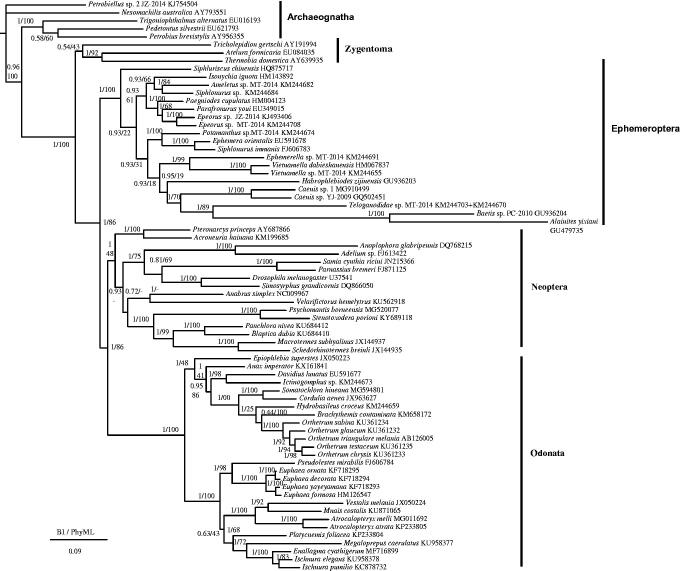

The phylogenetic relationship based on BI and PhyML analyses (Figure 1) showed that Ephemeroptera was the basal group of Pterygota and that Odonata was a sister clade to Neoptera, as also shown in Zhang et al. (2008). Among Ephemeroptera, Siphluriscus chinensis was the most primitive clade as well as the results of Ogden et al. (2009), Li et al. (2014), and Zhou and Peters (2003).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the relationships among 71 species of Pterygota based on the nucleotide dataset of 13 mitochondrial protein coding genes. The tree includes 20 Ephemeroptera species, 27 Odonata species, and 16 Neoptera species, as well as five Archaeognatha and three Zygentoma species as the outgroups (Clary et al. 1982; Nardi et al. 2003; Cameron et al. 2004; Yamauchi et al. 2004; Cook et al. 2005; Cameron et al. 2006; Podsiadlowski 2006; Stewart and Beckenbach 2006; Cameron and Whiting 2007; Carapelli et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008; Comandi et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2009; Sheffield et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2010; Cameron et al. 2012; Jong et al. 2012; Li et al. 2014; Lorenzo-Carballa et al. 2014; Tang et al. 2014; Ma et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2015; Cheng et al. 2016; Feindt et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016; Yong et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). Numbers above the nodes indicate the posterior probabilities of BI and the bootstrap values of PhyML. The GenBank numbers of all species are shown in the figure.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Blanke A, Wipfler B, Letsch H, Koch M, Beckmann F, Beutel R, Misof B. 2012. Revival of Palaeoptera-head characters support a monophyletic origin of Odonata and Ephemeroptera (Insecta). Cladistics. 28:560–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Barker SC, Whiting MF. 2006. Mitochondrial genomics and the new insect order Mantophasmatodea. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 38:274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Whiting MF. 2007. Mitochondrial genomic comparisons of the subterranean termites from the Genus Reticulitermes (Insecta: Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Genome. 50:188–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Lo N, Bourguignon T, Svenson GJ, Evans TA. 2012. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of termites (Blattodea: Termitoidae): robust support for interfamilial relationships and molecular synapomorphies define major clades. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 65:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Miller KB, D'Haese CA, Whiting MF, Barker SC. 2004. Mitochondrial genome data alone are not enough to unambiguously resolve the relationships of Entognatha, Insecta and Crustacea sensu lato (Arthropoda). Cladistics. 20:534–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carapelli A, Liò P, Nardi F, van der Wath E, Frati F. 2007. Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial protein coding genes confirms the reciprocal paraphyly of Hexapoda and Crustacea. BMC Evol Biol. 7:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. 2000. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 17:540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XF, Zhang LP, Yu DN, Storey KB, Zhang JY. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genomes of four cockroaches (Insecta: Blattodea) and phylogenetic analyses within cockroaches. Gene. 586:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary DO, Goddard JM, Martin SC, Fauron CM, Wolstenholme DR. 1982. Drosophila mitochondrial DNA: a novel gene order. Nucleic Acids Res. 10:6619–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comandi S, Carapelli A, Podsiadlowski L, Nardi F, Frati F. 2009. The complete mitochondrial genome of Atelura formicaria (Hexapoda: Zygentoma) and the phylogenetic relationships of basal insects. Gene. 439:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CE, Yue Q, Akam M. 2005. Mitochondrial genomes suggest that hexapods and crustaceans are mutually paraphyletic. Sci Rep. 272:1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feindt W, Osigus H, Herzog RJ, Mason CE, Hadrys H. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of the neotropical helicopter damselfly Megaloprepus caerulatus (Odonata: Zygoptera) assembled from next generation sequencing data. Mitochondrial DNA B. 1:497–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XY, Zhang SS, Zhang LP, Yu DN, Zhang JY. 2018. The complete mitochondrial genome of Epeorus herklotsi (Ephemeroptera: Heptageniidae) and its phylogeny. Mitochondrial DNA B. 3:303–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 52:696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MC, Wang YY, Liu XY, Li WH, Kang ZH, Wang K, Li XK, Yang DJ. 2015. The complete mitochondrial genome and its remarkable secondary structure for a stonefly Acroneuria hainana Wu (Insecta: Plecoptera, Perlidae). Gene. 557:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata K, Sasaki G, Ogawa J, Miyata T, Su ZH. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships among insect orders based on three nuclear protein-coding gene sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 58:169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong S, Kim T, Park JS, Kim MJ, Pil D, Yang J, Kim SG, Jin BR, Han YS. 2012. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitochondrial genome of eri-silkworm, Samia cynthia ricini (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). J Asia-Pac Entomol. 15:162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EM, Hong MY, Kim MI, Park HC. 2009. The complete mitogenome sequences of the palaeopteran insects Ephemera orientalis (Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae) and Davidius lunatus (Odonata: Gomphidae). Genome. 52:810–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CP, Chen MY, Huang JP. 2010. The complete mitochondrial genome and phylogenomics of a damselfly, Euphaea formosa support a basal Odonata within the Pterygota. Gene. 468:20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Qin JC, Zhou CF. 2014. The phylogeny of Ephemeroptera in Pterygota revealed by the mitochondrial genome of Siphluriscus chinensis (Hexapoda: Insecta). Gene. 545:132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Carballa MO, Thompson DJ, Cordero-Rivera A, Watts PC. 2014. Next generation sequencing yields the complete mitochondrial genome of the scarce blue-tailed damselfly, Ischnura pumilio. Mitochondrial DNA. 25:247–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J, Giribet G. 2006. Further use of nearly complete 28S and 18S rRNA genes to classify Ecdysozoa: 37 more arthropods and a kinorhynch. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 40:772–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, He K, Yu PP, Cheng XF, Yu DN, Zhang JY. 2015. The complete mitochondrial genomes of three bristletails (Insecta: Archaeognatha): the paraphyly of Machilidae and insights into Archaeognathan phylogeny. PLoS One. 10:e0117669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusemann K, Reumont von BM, Simon S, Roeding F, Strauss S, Kuck P. 2010. A phylogenomic approach to resolve the arthropod tree of life. Mol Biol Evol. 27:2451–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi F, Spinsanti G, Boore JL, Carapelli A, Dallai R, Frati F. 2003. Hexapod origins: monophyletic or paraphyletic?. Science. 299:1887–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden TH, Gattolliat J, Sartori M, Staniczek A, Soldán T, Whiting M. 2009. Towards a new paradigm in mayfly phylogeny (Ephemeroptera): combined analysis of morphological and molecular data. Syst Entomol. 34:616–634. [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlowski L. 2006. The mitochondrial genome of the bristletail Petrobius brevistylis (Archaeognatha: Machilidae). Insect Mol Biol. 15:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier JC, Shultz JW, Zwick A, Hussey A, Ball B, Wetzer R, Martin JW, Cunningham CW. 2010. Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences. Nature. 463:1079–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 61:539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield NC, Song H, Cameron SL, Whiting MF. 2009. Nonstationary evolution and compositional heterogeneity in beetle mitochondrial phylogenomics. Syst Biol. 58:381–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N, Li H, Song F, Cai W. 2016. Molecular phylogeny of Polyneoptera (Insecta) inferred from expanded mitogenomic data. Sci Rep. 6:36175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JB, Beckenbach AT. 2006. Insect mitochondrial genomics 2: the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a giant stonefly, Pteronarcys princeps, asymmetric directional mutation bias, and conserved plecopteran A + T-region elements. Genome. 48:815–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Tan MH, Meng GL, Yang SZ, Su X, Liu SL, Song WH, Li YY, Wu Q, Zhang AB, Zhou X. 2014. Multiplex sequencing of pooled mitochondrial genomes a crucial step toward biodiversity analysis using mito-metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:e166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Trueman JWH, Rambaut A, Welch JJ. 2013. Relaxed phylogenetics and the palaeoptera problem: resolving deep ancestral splits in the insect phylogeny. Syst Biol. 62:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi MM, Miya M, Nishida M. 2004. Use of a PCR-based approach for sequencing whole mitochondrial genomes of insects: two examples (cockroach and dragonfly) based on the method developed for decapod crustaceans. Insect Mol Biol. 13:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Ren Q, Huang Y. 2016. Complete mitochondrial genomes of three crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) and comparative analyses within Ensifera mitogenomes. Zootaxa. 4092:529–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong HS, Song SL, Suana IW, Eamsobhana P, Lim PE. 2016. Complete mitochondrial genome of Orthetrum dragonflies and molecular phylogeny of Odonata. Biochem Syst Ecol. 69:124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Yu PP, Cheng XF, Ma Y, Yu DN, Zhang JY. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of Brachythemis contaminata (Odonata: Libellulidae). Mitochondrial DNA A. 27:2272–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JY, Zhou CF, Gai YH, Song DX, Zhou KY. 2008. The complete mitochondrial genome of Parafronurus youi (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) and phylogenetic position of the Ephemeroptera. Gene. 424:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JY, Song DX, Zhou KY. 2008. The complete mitochondrial genome of the bristletail Pedetontus silvestrii (Archaeognatha: Machilidae) and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within four bristletails. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 101:1131–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wang XT, Wen CL, Wang MY, Yang XZ, Yuan ML. 2017. The complete mitochondrial genome of Enallagma cyathigerum (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) and phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA B. 2:640–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LP, Cai YY, Yu DN, Stroey KB, Zhang JY. 2017. The complete mitochondrial genome of Psychomantis borneensis (Mantodea: Hymenopodidae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 3:42–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LP, Yu DN, Stroey KB, Cheng HY, Zhang JY. 2018. Higher tRNA gene duplication in mitogenomes of praying mantises (Dictyoptera, Mantodea) and the phylogeny within Mantodea. Int J Biol Macromol. 111:787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou CF, Peters JG. 2003. The nymph of Siphluriscus chinensis and additional imaginal description: a living mayfly with Jurassic origins (Siphluriscidae new family: Ephemeroptera). Fla Entomol. 86:345–352. [Google Scholar]