Abstract

Background:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are environmentally persistent chemicals commonly used in the production of household and consumer goods. While exposure to PFAS has been associated with greater adiposity in children and adults, less is known about associations with gestational weight gain (GWG).

Methods:

We quantified using mass spectrometry perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), perfluorohexanesulfanoate (PFHxS) and perfluorononanoate (PFNA) in maternal serum from 18±5 weeks’ gestation (mean±standard deviation (std)) in a prospective pregnancy and birth cohort (2003–2006, Cincinnati, Ohio) (n=277). After abstracting weight data from medical records, we calculated GWG from 16±2 weeks’ gestation (mean±std) to the measured weight at the last visit or at delivery, rate of weight gain in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters (GWR), and total weight gain z-scores standardized for gestational age at delivery and pre-pregnancy BMI. We investigated covariate-adjusted associations between individual PFAS using multivariable linear regression; we assessed potential effect measure modification (EMM) by overweight/obese status (pre-pregnancy BMI<25 kg/m2 v. ≥25 kg/m2). Using weighted quantile sum regression, we assessed the combined influence of these four PFAS on GWG and GWR.

Results:

Each doubling in serum concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA was associated with a small increase in GWG (range 0.5–0.8 lbs) and GWR (range 0.03–0.05 lbs/week) among all women. The association of PFNA with GWG was stronger among women with BMI≥25 kg/m2 (β=2.6 lbs; 95% CI:−0.8, 6.0) than those with BMI<25 kg/m2 (β=−1.0 lbs; 95% CI:−3.8, 1.8; p-EMM=0.10). We observed associations close to the null between PFAS and z-scores and between the PFAS exposure index (a combined summary measure) and the outcomes.

Conclusion:

Although there were consistent small increases in gestational weight gain with increasing PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA serum concentrations in this cohort, the associations were imprecise. Additional investigation of the association of PFAS with GWG in other cohorts would be informative and could consider pre-pregnancy BMI as a potential modifier.

Keywords: Cohort, gestational weight gain, PFAS, serum

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of environmentally persistent synthetic chemicals with a wide range of uses because of their oil and water-resistant properties (ATSDR, 2018). PFAS can be found in coatings on some fabrics and food containers, non-stick household products, floor polishes, and fire-fighting foams (ATSDR, 2018). Human exposure can occur through food, drinking water, and use of consumer products; some PFAS can accumulate in the body and have biological half-lives on the order of years (ATSDR, 2018). The ubiquity of PFAS have been demonstrated in studies of the U.S. population including pregnant women (CDC, 2019; Jain, 2013; Woodruff et al., 2011).

Gestational weight gain (GWG) is an important risk factor in the development of childhood obesity (Hinkle et al., 2012; Oken et al., 2007), and offspring of women with either excessive or inadequate maternal GWG experience greater risk of hypertension and insulin resistance in childhood (Tam et al., 2018). However, only a few studies have examined exposure to PFAS and GWG (Liu et al., 2018). Two previous studies have suggested that higher maternal serum concentrations of PFOS during pregnancy are associated with greater GWG and that the association may be modified by maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (Ashley-Martin et al., 2016; Jaacks et al., 2016). A Canadian cohort study observed stronger effects among women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy (Ashley-Martin et al., 2016), whereas, the U.S. based study observed stronger effects among women with normal BMI before pregnancy (Jaacks et al., 2016). However, neither of these studies considered the influence of exposure to multiple PFAS on GWG. A sub-study of 905 women in the larger Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children in Great Britain found no association between maternal PFOA, PFOS and PFHxS concentrations in serum and GWG, but did find a weak positive association between PFNA and GWG (Marks et al., 2019). There were no differences observed by BMI status. Studies of weight gain in non-pregnant women and men offer additional supporting evidence. In a randomized weight-loss trial among overweight/obese adults, participants who had higher plasma concentrations of PFAS at the time of randomization experienced greater weight regain during the follow-up period after the initial weight loss, especially female participants (Liu et al., 2018), suggesting that PFAS may disrupt regulation of weight gain.

In the present study, we used data from a well-characterized pregnancy and birth cohort to investigate the influence of four prevalent PFAS (perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), perfluorohexanesulfanoate (PFHxS) and perfluorononanoate (PFNA)) alone or in mixtures on gestational weight gain during pregnancy.

Methods

Study participants

The Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study examines early life environmental chemical exposures and children’s health (Braun et al., 2017). This prospective pregnancy and birth cohort recruited eligible women from March 2003 to January 2006 from nine prenatal practices in the greater Cincinnati, OH metropolitan area. Clinic records and phone interviews with women determined eligibility, including being ≥ 18 years old, pregnant (16±3 weeks gestation), English speakers, living in a home built in or before 1978, planning to continue prenatal care and deliver at a study affiliated practice, and planning to live in the study area for the next year. Women are not eligible if they had history of HIV infection, pre-existing diabetes, if they took medications for seizures or thyroid disorders, or if they had radiation or chemotherapy. There were 1,263 eligible women, and 37% enrolled (n=468) (Braun et al., 2017). Of these, we followed 83% (n=389) through live birth of a singleton infant. The Institutional Review Boards of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and all delivery hospitals approved the study protocol. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) deferred to the CCHMC IRB as the IRB of record. All mothers provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study. We excluded women with gestational diabetes or hypertension in pregnancy from the analysis (n=44), as these complications may influence maternal weight gain.

Exposure Assessment

We collected maternal blood samples during pregnancy. We quantified the concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA in serum using online solid phase extraction coupled to high performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry (Kato et al., 2011). The majority of samples analyzed were from the 16-week visit (85%), but in instances where women had insufficient serum volume at that visit, we analyzed samples from the 26-week visit (10%) or at delivery (5%) (mean±standard deviation (std) 18±5 weeks’ gestation). Limits of detection were 0.1 ng/mL (PFOA, PFHxS), and 0.2 ng/mL (PFOS) and 0.082 ng/mL (PFNA). We included blanks and quality control materials with each batch of samples analyzed.

Outcome Ascertainment

We abstracted weight data from the women’s medical records to calculate GWG and rate of weight gain (GWR). We also collected self-reported pre-pregnancy weight from participants. We calculated GWG using abstracted weight from early pregnancy (mean ±std)=16±2 weeks’ gestation) and the weight at the last visit or at delivery. To calculate pre-pregnancy BMI, a two-step process predicted weight when self-reported pre-pregnancy weight data were missing (25%). First, we calculated bivariate correlations between multiple variables and pre-pregnancy BMI and selected those covariates with correlation p-values of 0.20 or less. Then, we used the R package SuperLearner (SuperLearner (2.0–22); van der Laan Mark et al., 2007). This is an ensemble learning method which uses those variables and a series of algorithms (i.e., regression methods) to predict missing values by weighting the algorithms contribution to the prediction (Supplemental Material; Supplemental SuperLearner Methods). Covariates selected for prediction included maternal education, marital status, race, insurance status, parity, household income, log10- serum cotinine from pregnancy, height in inches, and measured weight from between 13–19 weeks of pregnancy.

We used pre-pregnancy weight to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG over the full pregnancy. These two measures computed pre-pregnancy BMI-specific gestational age-standardized z-scores for total GWG using charts created from a sample of normal and overweight women at Magee-Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA (1998–2008) with uncomplicated, singleton pregnancies (Hutcheon et al., 2013). We also calculated total GWG z-scores standardized on gestational age based on the distribution of GWG among normal weight women to allow for the evaluation of potential effect measure modification of the associations of PFAS with z-scores according to pre-pregnancy BMI<25 kg/m2 (normal/underweight) versus BMI≥25 kg/m2 (overweight/obese)(Pugh et al., 2016).

Covariate Data

Trained research staff administered a computer-assisted questionnaire to all participants during their second trimester to collect reproductive and medical histories and information on sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors. Staff also derived reproductive histories from medical chart review. We measured serum cotinine, a biomarker of exposure to active and second-hand tobacco smoke, at 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation and averaged if more than one measure was available (Bernert et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis

We examined associations between individual PFAS and GWG parameters using multivariable linear regression. PFAS measurements were examined as log2-transformed continuous variables. We adjusted all models for gestational week at blood draw for PFAS measurements and sociodemographic, perinatal, and lifestyle factors. We selected the following variables a priori for adjustment based on previously observed associations with the exposure and outcome in the literature: maternal education (<Bachelor’s/Bachelor’s+), maternal age, race (non-Hispanic White/Other), pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, log10-serum cotinine, alcohol use during pregnancy, gestational week of blood draw, parity (nulliparous/parous), and gestational age at delivery. There were two exceptions. Specifically, models for GWG rate did not include gestational age at delivery, and the model for z-score did not include pre-pregnancy BMI or gestational age at delivery. In these instances, the covariate variable(s) were implicitly included in the definition of the outcome.

We assessed potential effect measure modification (EMM) by pre-pregnancy BMI by adding a product interaction term to the regression models for overweight/obese status (pre-pregnancy BMI<25 kg/m2 v. BMI≥25 kg/m2). We performed sensitivity analyses to examine any potential influence of gestational age at measurement of PFAS, use of predicted pre-pregnancy weights, and potential EMM by parity by restricting to women with a PFAS measurement from the 16-week visit, women that reported a pre-pregnancy weight, and nulliparous women, respectively. As exploratory analysis in the high BMI group, we further examined EMM by adding in two product interaction terms into the model for GWG- one to examine overweight women and one for obese group separately.

We used weighted-quantile-sum regression (WQS) to examine the combined influence of the four individual PFAS on GWG and refer to this measure as a PFAS exposure index (Carrico et al., 2015). We analyzed all women using WQS regression models and stratified by pre-pregnancy BMI status.

We used restricted cubic splines to examine the shape of the relationship between PFAS serum concentrations and GWG was appropriate (Desquilbet and Mariotti, 2010). We used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) for linear regression models and R statistical software (version 3.3.3) to complete WQS models with the package gWQS (version 1.1.0) with 1000 bootstrap samples, constrained to positive coefficients.

Results

We had complete data on 277 pregnant women who did not have gestational diabetes and/or hypertension. The majority of the study population was 25–34 years old (63.5%), non-Hispanic white (66.1%), held a Bachelor’s degree or higher (53.4%), and was married (69.7%) (Table 1). Serum cotinine measurements indicated that few women were active (10.1%) smokers, while 43.3% of the women had ever drank alcohol during pregnancy. Approximately, 27% of women were classified as overweight and 19% as obese based on pre-pregnancy BMI≥25 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics of participants in the HOME Study, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2003–2006.

| Characteristic | n (%) | Weight Gain (lbs) Mean (STD) | Weight Gain Rate (lbs/week) Mean (STD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 277 (100.0) | 21.8 (10.2) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Age | |||

| 18–25 years | 55 (19.9) | 23.5 (12.5) | 1.2 (0.6) |

| 25–35 years | 176 (63.5) | 22.0 (9.8) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| >35 years | 46 (16.6) | 19.4 (8.4) | 1.0 (0.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 183 (66.1) | 22.2 (8.6) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| Black | 79 (28.5) | 20.8 (13.2) | 1.0 (0.6) |

| Other | 15 (5.4) | 22.9 (11.4) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Education | |||

| High School or less | 54 (19.5) | 20.4 (13.5) | 1.0 (0.6) |

| Tech school or some college | 75 (27.1) | 21.7 (11.2) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Bachelors or more | 148 (53.4) | 22.5 (8.2) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Not Married | 84 (30.3) | 20.9 (13.4) | 1.0 (0.6) |

| Married | 193 (69.7) | 22.3 (8.5) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| Household Income | |||

| >$80,000 | 52 (18.8) | 19.9 (14.7) | 1.0 (0.7) |

| $40–80,000 | 53 (19.1) | 21.9 (10.5) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| $20–40,000 | 89 (32.1) | 22.8 (8.8) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| <$20,000 | 83 (30.0) | 21.9 (7.9) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| Nulliparous | |||

| Yes | 124 (44.8) | 22.5 (9.4) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| No | 153 (55.2) | 21.3 (10.9) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) (pre-pregnancy) | |||

| <25 | 150 (54.2) | 23.4 (9.0) | 1.3 (0.4) |

| 25–30 | 74 (26.7) | 21.9 (9.4) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| >30 | 53 (19.1) | 17.4 (13.3) | 0.9 (0.6) |

| Serum Cotinine (ng/mL) a | |||

| <0.015 (unexposed) | 108 (39.0) | 19.8 (9.7) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| 0.015 – 3 (secondhand) | 141 (50.9) | 22.8 (9.9) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| >3 ng/mL (active) | 28 (10.1) | 24.6 (12.7) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Alcohol During Pregnancy b | |||

| Never | 157 (56.7) | 22.8 (10.3) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Ever | 120 (43.3) | 20.6 (10.1) | 1.1 (0.5) |

Serum cotinine at 16 weeks gestation estimated environmental tobacco exposure during pregnancy and categorized based on threshold values (Benowitz et al., 2009)

Self-reported maternal consumption of alcohol during pregnancy

Median serum concentrations were 5.4 ng/mL (IQR=3.7–7.8) for PFOA, 13.7 ng/mL (IQR=9.6–18.0) for PFOS, 1.5 ng/mL (IQR=0.9–2.3) for PFHxS, and 0.9 ng/mL (IQR=0.7–1.2) for PFNA. The four PFAS examined were weakly to moderately correlated (Spearman correlation coefficients=0.34–0.57, p<0.0001, Supplemental Material, Table S1). None of the PFAS concentrations were below the limits of detection.

From early pregnancy to delivery, women gained a mean weight of 21.8 lbs (std=10.2) at a mean rate of 1.2 lbs/week (std=0.5) (Table 1). Women ages 18 to 25 years old gained slightly more weight (mean= 23.6±12.5 lbs) than women over 35 years old (mean=19.4±8.4 lbs). GWG did not differ greatly by maternal race, education, marital status, household income, parity, or alcohol use during pregnancy. Mean weight gain was greater among women with normal pre-pregnancy weight (BMI<25 kg/m2, 23.4 ± 9.0 lbs) compared to overweight women (BMI=25–30 kg/m2, 21.9 ± 9.4lbs) and obese women (BMI>30 kg/m2, 17.4 ±13.3 lbs). On average, pregnancy weight gain was considered optimal by Institute of Medicine guidelines, although average gestational weight gain among normal weight women (mean=23.4 lbs) was slightly less than recommended weight gain during pregnancy (optimal range: 25 to 35 lbs) (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013). Women who were active smokers or exposed to secondhand smoke had greater weight gain and rate of weight gain compared to women who did not smoke or were not exposed to secondhand smoke.

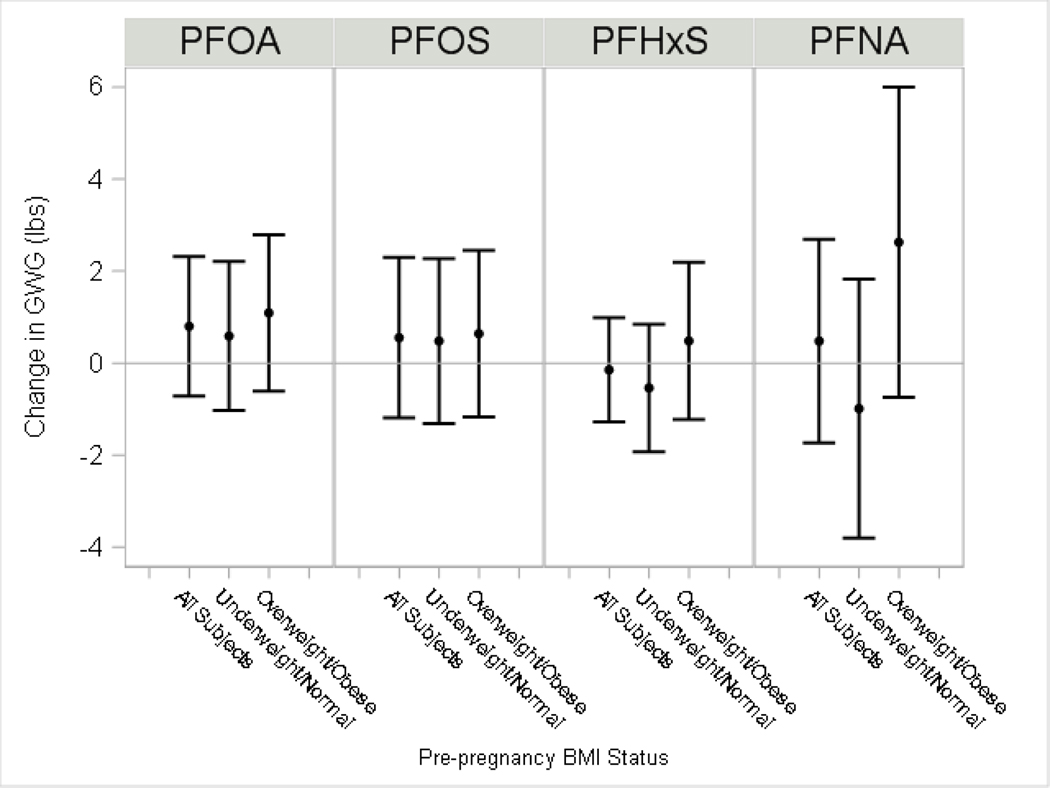

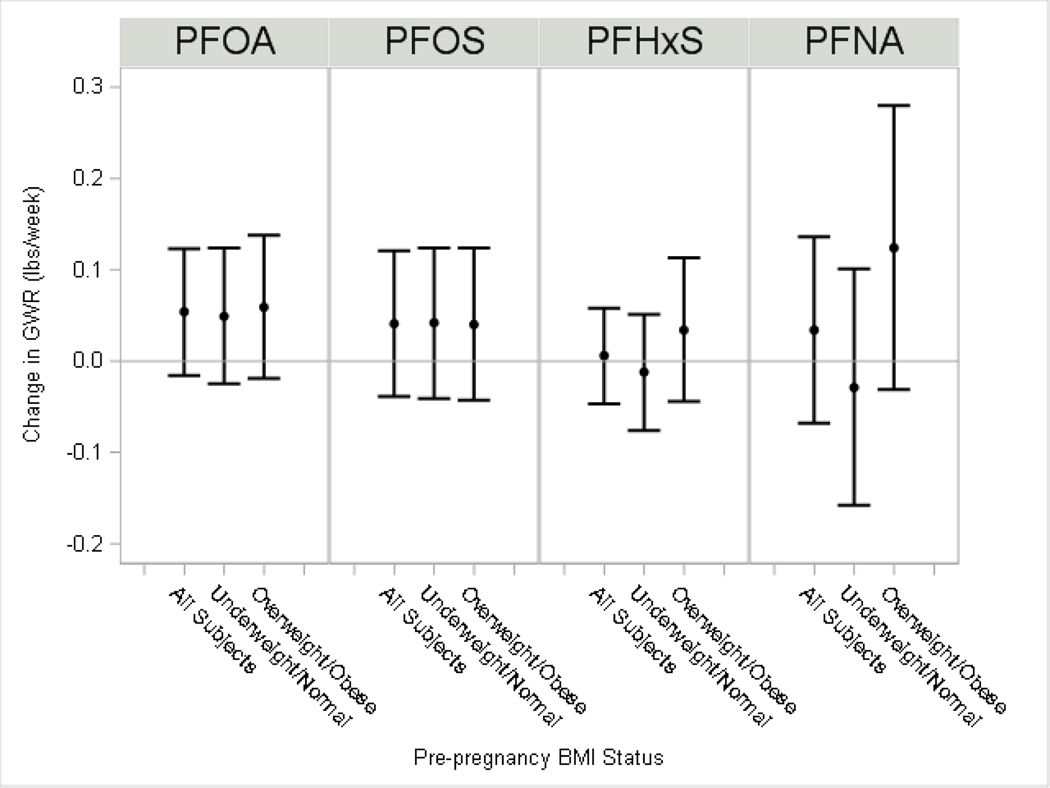

Among all women, we observed subtle increases in GWG (range 0.5–0.8 lbs) and GWR (range 0.03–0.05 lbs/week) with each two-fold increase in serum PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA (Figure 1 and 2; Supplemental Material, Table S2). We observed little differences in weight gain for PFHxS (β =−0.1 lbs) or weight gain rate (β =0.01 lbs/week). We observed suggestive evidence of EMM by pre-pregnancy overweight/obese status for PFNA, where the association of PFNA with GWG was stronger among women with BMI≥25 kg/m2 (β=2.6 lbs; 95% CI:−0.8, 6.0) than among women with BMI<25 kg/m2 (β=−1.0 lbs; 95% CI:−3.8, 1.8; p-EMM=0.10).

Figure 1: Adjusted differences in gestational weight gain per each doubling in maternal serum PFAS.

The model for all subjects adjusted for maternal education, age at delivery, race, pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, log10-serum cotinine from pregnancy, alcohol use during pregnancy, gestational week of blood draw, parity and gestational age at delivery. Model by pre-pregnancy BMI status additionally included a product interaction term for PFAS. The p-value for effect modification by overweight/obesity status (p-EMM): PFOA, p-EMM=0.45; PFOS p-EMM=0.73; PFHxS p-EMM=0.33; PFNA p-EMM=0.10).

Figure 2: Adjusted difference in gestational weight gain rate per each doubling in maternal serum PFAS.

The model for all subjects adjusted for maternal education, age at delivery, race, pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, log10-serum cotinine from pregnancy, alcohol use during pregnancy, gestational week of blood draw and parity. Stratified model by pre-pregnancy BMI status additionally included a product interaction term for PFAS. The p-value for effect modification by overweight/obesity status (p-EMM): PFOA, p-EMM=0.75; PFOS p-EMM=0.94; PFHxS p-EMM=0.33; PFNA p-EMM=0.13).

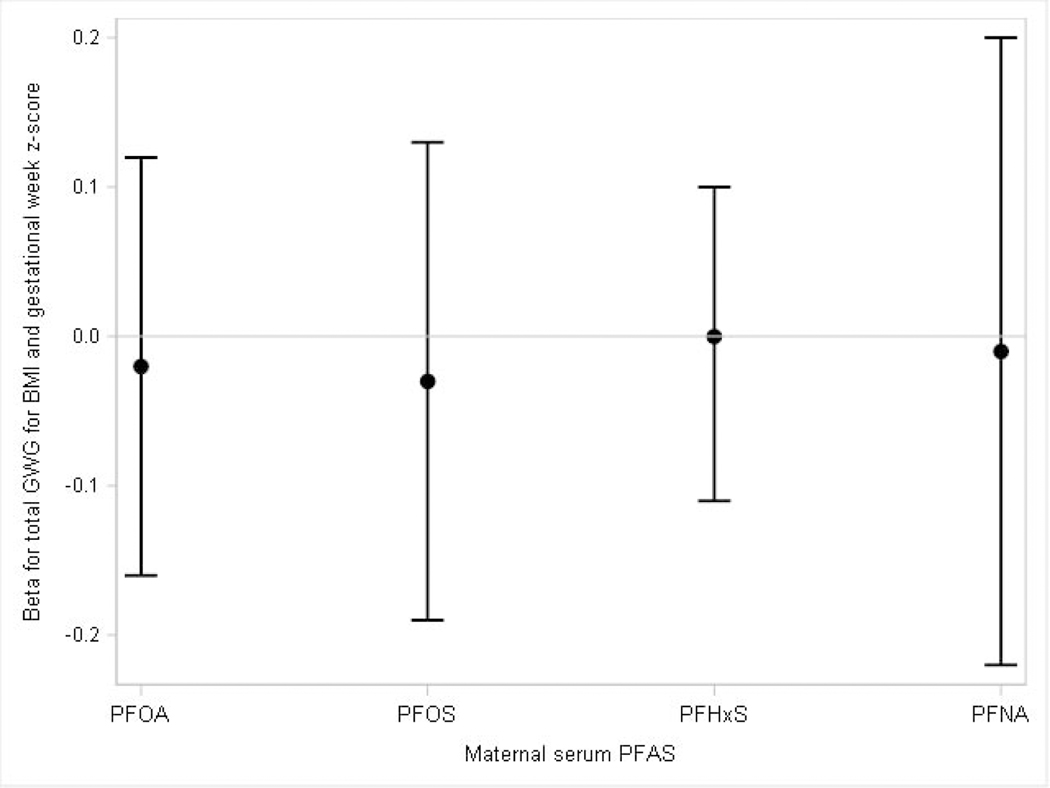

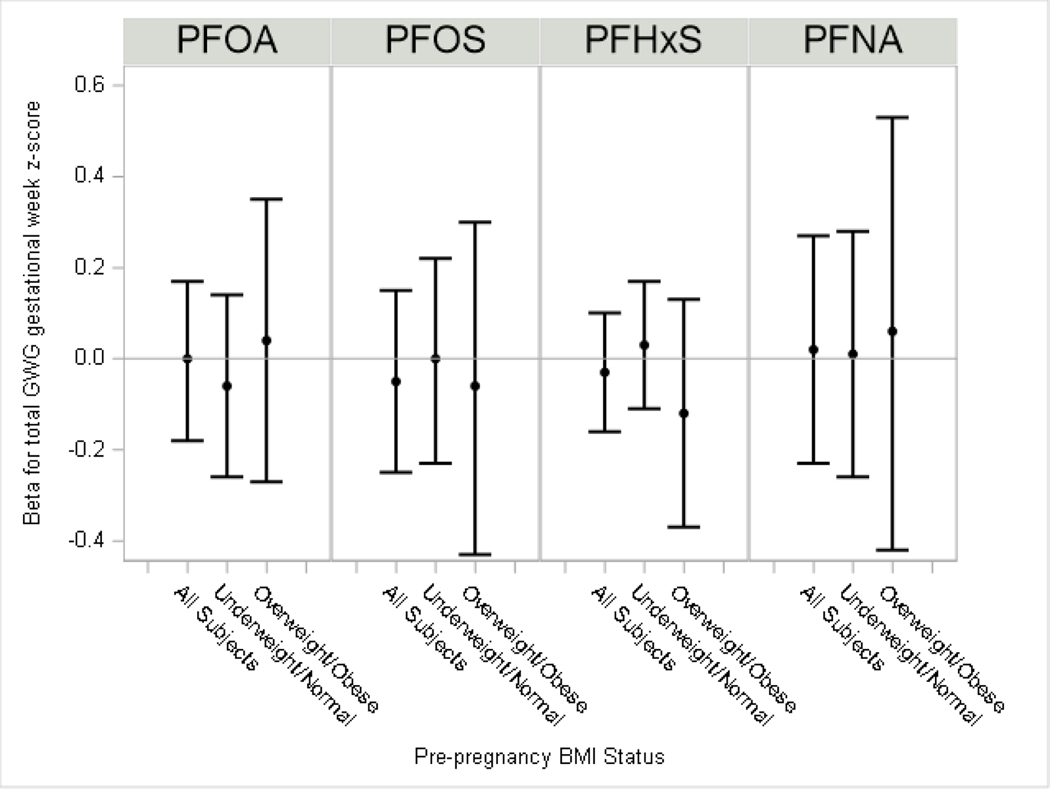

PFAS were not associated with pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational age of delivery specific total GWG z-scores (Figure 3, Supplemental Material, Table S2) or with total GWG z-scores standardized for gestational age and when we assessed for potential EMM by BMI<25 kg/m2 (normal/underweight) versus BMI≥25 kg/m2 (overweight/obese) (Figure 4, Supplemental Material, Table S2).

Figure 3: Adjusted difference in total gestational weight gain z-scores per each doubling in maternal serum PFAS.

The model adjusted for maternal education, age at delivery, race, household income, log10-serum cotinine from pregnancy, alcohol use during pregnancy, gestational week of blood draw and parity.

Figure 4: Adjusted difference in total gestational weight gain z-scores per each doubling in maternal serum PFAS.

The model for all subjects adjusted for maternal education, age at delivery, race, household income, pre-pregnancy BMI, log10-serum cotinine from pregnancy, alcohol use during pregnancy, gestational week of blood draw and parity. Models by pre-pregnancy BMI further included an interaction term for overweight/obese status and PFAS. The p-value for effect modification by overweight/obesity status (p-EMM): PFOA, p-EMM=0.94; PFOS p-EMM=0.66; PFHxS p-EMM=0.38; PFNA p-EMM=0.62).

We found no appreciable differences when restricting the analysis to women with samples from the 16-week pregnancy visit (85%) (Supplemental Material, Table S3). When we excluded women with predicted pre-pregnancy weights (n=70), the results were similar to the full analysis among all women for GWG and GWR, although there were some differences from the main analysis when examining associations by pre-pregnancy overweight/obese status (Supplemental Material, Table S4). The largest differences were noted in the overweight/obese group for PFOS and PFNA, but generally there was little pattern or consistency. When restricting to women who were nulliparous (n=124), the association of weight gain with PFOS (β =2.3 lbs, 95% CI −0.03, 4.5) and PFNA (β =2.7 lbs, 95% CI −0.3, 5.8) became stronger (Supplemental Material, Table S5). However, confidence intervals were wider with the smaller sample.

Among all mothers, the PFAS exposure index was not strongly associated with GWG (WQS β =0.3 lbs; 95% CI: −1.1, 1.7) and not associated with GWR (WQS β = 0.0 lbs/week; 95% CI: −0.1, 0.1) (Supplemental Material, Table S6). The PFAS exposure index showed similar results for both BMI-specific gestational age-standardized total weight gain z-score (WQS β= 0.0, 95% CI: −0.1, 0.1) and gestational age-standardized total weight gain z-score (WQS β=−0.1, 95% CI: −0.2, 0.1). Associations of the PFAS exposure index with the outcomes were similar across strata of BMI<25 kg/m2 and BMI≥25 kg/m2.

When we further explored EMM in our primary analysis of GWG and GWR by finer categories of BMI, we observed evidence of EMM for all PFAS only in obese women (BMI>30 kg/m2). (Supplemental Material, Table S7). The number of women in this category was small (n=53) but the results were consistent across all PFAS.

Discussion

Overall, we did not observe strong evidence of associations of individual or aggregated PFAS serum concentrations during pregnancy with GWG in the HOME Study. Our findings are broadly in line with prior studies suggesting that greater PFAS concentrations in blood are associated with modest increases in weight gain during pregnancy (Ashley-Martin et al., 2016; Jaacks et al., 2016; Marks et al., 2019). There was limited evidence of any differences in associations by pre-pregnancy BMI status, although some indication for PFNA of a stronger positive association for GWG among mothers who were overweight or obese (BMI≥25 kg/m2) prior to pregnancy. Our exploratory analyses indicated that positive associations of GWG and PFAS may be strongest in obese women (BMI>30 kg/m2) but given the small number in this cohort (n=53), studies of larger cohorts are necessary to fully elucidate these differences. Maternal PFOS, PFHxS and PFNA concentrations in the HOME Study are similar to those found in pregnant women from the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), although the median PFOA concentration in the HOME Study was approximately two times higher (Braun et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018).

Epidemiological evidence to date on gestational weight gain and maternal exposure to PFAS consists of several other cohort studies suggesting some positive associations, but less consistency across specific PFAS and BMI status. The MIREC study in Canada reported that increases in GWG was associated with statistically significantly elevated concentrations of cord blood PFOA and PFOS (Ashley-Martin et al., 2016). Similar magnitude of associations were observed across categories of BMI (Ashley-Martin et al., 2016). The Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment (LIFE) Study in the United States did not find any association in women between GWG or concentrations of PFOA (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.02), PFOS (β=0.26, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.18) and PFNA (β=−0.03, 95% CI: −1.00, 0.94) (Jaacks et al., 2016). They did observe a significant positive association between PFOS and area under the gestational weight gain curve among women with a BMI < 25 kg/m2, but not among women with a BMI > 25 kg/m2 (Jaacks et al., 2016). Similar to the current study, the Avon study in the United Kingdom examined GWG and serum concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA modeled as log-transformed variables in linear regression models (Marks et al., 2019). PFAS concentration distributions were generally similar to the current study, but no associations were observed overall or by BMI, with the exception of a weak positive association for PFNA. Experimental studies in animals found that PFAS exposure is associated with increased expression of genes involved in adipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism (Watkins et al., 2015). Significant increases in body weight, serum insulin, and leptin was observed in mice with low in utero PFOA exposures, but only in mid-life (Hines et al., 2009).

Studies of weight gain not in pregnancy provide additional evidence for associations between GWG and PFAS. An earlier analysis in the HOME Study found in utero PFOA exposure was associated with greater adiposity at 8 years and a more rapid increase in BMI between 2–8 years (Braun et al., 2016). Another birth cohort study found that in utero PFOA exposure was associated with obesity in offspring at age 20 (Halldorsson et al., 2012). However, other studies have suggested that among females, PFOA exposure in childhood is associated with decreased BMI through adolescence (Fassler et al., 2019; Pinney et al., 2019). Collectively, these studies suggest that early life exposures to PFAS may have a role in weight status and cardiometabolic traits later in life. Results of a recent weight-loss study found that higher baseline PFAS concentrations were associated with greater weight regain in women, suggesting an interference of PFAS with body weight regulation and metabolism (Liu et al., 2018), implying that PFAS may also influence weight gain in adults.

Similarly, prior evidence from epidemiologic studies support potential associations of PFAS with thyroid hormones in adults, which may influence weight gain (Kim et al., 2018). A recent review of the few studies specific to pregnant women suggested positive associations between maternal PFAS exposure and TSH levels (Ballesteros et al., 2017). The Chemicals, Health and Pregnancy (CHirP) study, based in Vancouver, Canada, observed associations between maternal PFAS concentrations and higher levels of maternal thyroid hormones (Webster et al., 2014). By contrast, Project VIVA, based in Boston, MA, reported inverse associations of individual maternal plasma PFAS and combined exposures to multiple PFAS in pregnancy with maternal free thyroxine and maternal free thyroxine index, respectively(Preston et al., 2020; Preston et al., 2018). Although prior literature generally indicates that PFAS are associated with maternal thyroid hormones, a recent analysis of the current study population determined that exposure to PFAS, considered individually or as mixtures, were generally not associated with levels of any thyroid hormones in maternal serum (Lebeaux et al., 2020). However, this analysis was limited to a subset (n=185) of women in the current study and may have had limited statistical power to identify associations.

PFAS have been somewhat inconsistently associated with the metabolic syndrome and its components (Christensen et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2010), but in a recent NHANES analysis, PFNA was associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome and increased waist circumference (Christensen et al., 2019). A pilot study of 122 adults in Croatia found background exposure to PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA was marginally associated with increased risk of cardiometabolic traits and metabolic syndrome (Chen et al., 2019). Other studies have suggested associations between PFAS exposure and increased concentrations of total cholesterol, uric acid, glucose, insulin resistance, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Cardenas et al., 2017; Steenland et al., 2009; Steenland et al., 2010).

This study has several strengths and limitations. Due to the prospective study design, we were able to use medical chart data to calculate GWG and estimate exposure using an objective serum measurement in early pregnancy. Plasma volumes increase during pregnancy, which may dilute contaminants in serum, although this fact should be minimized by measuring PFAS concentrations earlier in pregnancy (Faupel-Badger et al., 2007). We also collected comprehensive information on confounding factors. However, inherent to all studies of environmental risk factors, unknown or unmeasured coexposures may lead to residual confounding. Although this study was limited by a relatively small sample size, future studies might employ larger sample sizes to further investigate PFNA, finer categories of possible EMM by pre-pregnancy BMI, and examine populations exposed to different levels and mixtures of PFAS.

Conclusions

We did not observe strong evidence of associations of individual or aggregated PFAS serum concentrations during pregnancy with GWG in the HOME Study. However, our findings are broadly in line with prior studies suggesting that greater PFAS concentrations in blood are associated with modest increases in weight gain. Exploratory analyses indicate that pre-pregnancy BMI may modify the association of PFAS with GWG, with the strongest effect of PFAS occurring among obese women, but studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to fully clarify these differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) grants P01 ES11261, R01 ES014575, R01 ES020349, R01 ES025214, and by National Institute of General Medicine (NIGMS) grant P20 GM104416 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). We acknowledge the technical assistance of K. Kato, J. Tao, and the late X. Ye (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC) in measuring the PFAS concentrations.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations

- PFAS

per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

- PFOA

perfluorooctanoate

- PFOS

perfluorooctanesulfonate

- PFHxS

perfluorohexanesulfanoate

- PFNA

perfluorononanoate

- GWG

gestational weight gain

- GWR

gestational weight gain rate

- BMI

body mass index

- HOME

Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment

- EMM

effect measure modification

- WQS

weighted-quantile-sum regression

- RCS

restricted cubic spline

Footnotes

Data sharing

Investigators interested in accessing data from the HOME Study should contact Drs Joseph M. Braun <joseph_braun_1@brown.edu> and Kimberly Yolton <kimberly.yolton@cchmc.org> to request a project proposal form. The HOME Study Data Sharing Committee meets regularly to review proposed research projects and ensure that they do not overlap with extant projects and are an efficient use of scarce resources (e.g. cord blood).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013. ACOG Committee opinion no. 548: weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 121, 210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley-Martin J, Dodds L, Arbuckle TE, Morisset AS, Fisher M, Bouchard MF, Shapiro GD, Ettinger AS, Monnier P, Dallaire R, Taback S, Fraser W, 2016. Maternal and Neonatal Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Relation to Gestational Weight Gain Int J Environ Res Public Health 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR, 2018. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls. Draft for Public Comment. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros V, Costa O, Iniguez C, Fletcher T, Ballester F, Lopez-Espinosa MJ, 2017. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and thyroid function in pregnant women and children: A systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Environ Int 99, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS, Holiday DB, Wang J, 2009. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. American journal of epidemiology 169, 236–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert JT, Jacob P 3rd, Holiday DB, Benowitz NL, Sosnoff CS, Doig MV, Feyerabend C, Aldous KM, Sharifi M, Kellogg MD, Langman LJ, 2009. Interlaboratory comparability of serum cotinine measurements at smoker and nonsmoker concentration levels: a round-robin study. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 11, 1458–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Chen A, Romano ME, Calafat AM, Webster GM, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, 2016. Prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and child adiposity at 8 years of age: The HOME study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24, 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Kalloo G, Chen A, Dietrich KN, Liddy-Hicks S, Morgan S, Xu Y, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, 2017. Cohort Profile: The Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study. Int J Epidemiol 46, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A, Gold DR, Hauser R, Kleinman KP, Hivert MF, Calafat AM, Ye X, Webster TF, Horton ES, Oken E, 2017. Plasma Concentrations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at Baseline and Associations with Glycemic Indicators and Diabetes Incidence among High-Risk Adults in the Diabetes Prevention Program Trial. Environmental health perspectives 125, 107001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico C, Gennings C, Wheeler DC, Factor-Litvak P, 2015. Characterization of Weighted Quantile Sum Regression for Highly Correlated Data in a Risk Analysis Setting. J Agr Biol Envir St 20, 100–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2019. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals Updated Tables, January 2019 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Environmental Health; Division of Laboratory Sciences, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Jandarov R, Zhou L, Calafat AM, Zhang G, Urbina EM, Sarac J, Augustin DH, Caric T, Bockor L, Petranovic MZ, Novokmet N, Missoni S, Rudan P, Deka R, 2019. Association of perfluoroalkyl substances exposure with cardiometabolic traits in an island population of the eastern Adriatic coast of Croatia. The Science of the total environment 683, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KY, Raymond M, Meiman J, 2019. Perfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic syndrome. Int J Hyg Environ Health 222, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquilbet L, Mariotti F, 2010. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Statistics in medicine 29, 1037–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassler CS, Pinney SE, Xie C, Biro FM, Pinney SM, 2019. Complex relationships between perfluorooctanoate, body mass index, insulin resistance and serum lipids in young girls. Environ Res 176, 108558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faupel-Badger JM, Hsieh CC, Troisi R, Lagiou P, Potischman N, 2007. Plasma volume expansion in pregnancy: implications for biomarkers in population studies. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 16, 1720–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Arbuckle TE, Wade M, Haines DA, 2013. Do perfluoroalkyl substances affect metabolic function and plasma lipids?--Analysis of the 2007–2009, Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) Cycle 1. Environ Res 121, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldorsson TI, Rytter D, Haug LS, Bech BH, Danielsen I, Becher G, Henriksen TB, Olsen SF, 2012. Prenatal exposure to perfluorooctanoate and risk of overweight at 20 years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environmental health perspectives 120, 668–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EP, White SS, Stanko JP, Gibbs-Flournoy EA, Lau C, Fenton SE, 2009. Phenotypic dichotomy following developmental exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in female CD-1 mice: Low doses induce elevated serum leptin and insulin, and overweight in mid-life. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 304, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle SN, Sharma AJ, Swan DW, Schieve LA, Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD, 2012. Excess gestational weight gain is associated with child adiposity among mothers with normal and overweight prepregnancy weight status. The Journal of nutrition 142, 1851–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon JA, Platt RW, Abrams B, Himes KP, Simhan HN, Bodnar LM, 2013. A weight-gain-for-gestational-age z score chart for the assessment of maternal weight gain in pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr 97, 1062–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaacks LM, Boyd Barr D, Sundaram R, Grewal J, Zhang C, Buck Louis GM, 2016. Pre-Pregnancy Maternal Exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants and Gestational Weight Gain: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RB, 2013. Effect of pregnancy on the levels of selected perfluoroalkyl compounds for females aged 17–39 years: data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2008. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A 76, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Basden BJ, Needham LL, Calafat AM, 2011. Improved selectivity for the analysis of maternal serum and cord serum for polyfluoroalkyl chemicals. Journal of chromatography. A 1218, 2133–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Moon S, Oh BC, Jung D, Ji K, Choi K, Park YJ, 2018. Association between perfluoroalkyl substances exposure and thyroid function in adults: A meta-analysis. PloS one 13, e0197244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeaux RM, Doherty BT, Gallagher LG, Zoeller RT, Hoofnagle AN, Calafat AM, Karagas MR, Yolton K, Chen A, Lanphear BP, Braun JM, Romano ME, 2020. Maternal serum perfluoroalkyl substance mixtures and thyroid hormone concentrations in maternal and cord sera: The HOME Study. Environ Res 185, 109395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Chen PC, Lin YC, Lin LY, 2009. Association among serum perfluoroalkyl chemicals, glucose homeostasis, and metabolic syndrome in adolescents and adults. Diabetes care 32, 702–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Dhana K, Furtado JD, Rood J, Zong G, Liang L, Qi L, Bray GA, DeJonge L, Coull B, Grandjean P, Sun Q, 2018. Perfluoroalkyl substances and changes in body weight and resting metabolic rate in response to weight-loss diets: A prospective study. PLoS Med 15, e1002502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks KJ, Jeddy Z, Flanders WD, Northstone K, Fraser A, Calafat AM, Kato K, Hartman TJ, 2019. Maternal serum concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances during pregnancy and gestational weight gain: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Reproductive toxicology 90, 8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Hatch EE, Webster TF, 2010. Exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals and cholesterol, body weight, and insulin resistance in the general U.S. population. Environmental health perspectives 118, 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW, 2007. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 196, 322 e321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinney SM, Windham GC, Xie C, Herrick RL, Calafat AM, McWhorter K, Fassler CS, Hiatt RA, Kushi LH, Biro FM, Breast C, the Environment Research P, 2019. Perfluorooctanoate and changes in anthropometric parameters with age in young girls in the Greater Cincinnati and San Francisco Bay Area. Int J Hyg Environ Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston EV, Webster TF, Claus Henn B, McClean MD, Gennings C, Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Pearce EN, Calafat AM, Fleisch AF, Sagiv SK, 2020. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and maternal and neonatal thyroid function in the Project Viva Cohort: A mixtures approach. Environ Int 139, 105728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston EV, Webster TF, Oken E, Claus Henn B, McClean MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Pearce EN, Braverman LE, Calafat AM, Ye X, Sagiv SK, 2018. Maternal Plasma per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Concentrations in Early Pregnancy and Maternal and Neonatal Thyroid Function in a Prospective Birth Cohort: Project Viva (USA). Environmental health perspectives 126, 027013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh SJ, Hutcheon JA, Richardson GA, Brooks MM, Himes KP, Day NL, Bodnar LM, 2016. Gestational weight gain, prepregnancy body mass index and offspring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and behaviour at age 10. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 123, 2094–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Tinker S, Frisbee S, Ducatman A, Vaccarino V, 2009. Association of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate with serum lipids among adults living near a chemical plant. American journal of epidemiology 170, 1268–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Tinker S, Shankar A, Ducatman A, 2010. Association of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) with uric acid among adults with elevated community exposure to PFOA. Environmental health perspectives 118, 229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SuperLearner (2.0–22), https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SuperLearner/index.html.

- Tam CHT, Ma RCW, Yuen LY, Ozaki R, Li AM, Hou Y, Chan MHM, Ho CS, Yang X, Chan JCN, Tam WH, 2018. The impact of maternal gestational weight gain on cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Diabetologia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan Mark J, Polley Eric C, Hubbard Alan E, 2007. Super Learner. sagmb 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins AM, Wood CR, Lin MT, Abbott BD, 2015. The effects of perfluorinated chemicals on adipocyte differentiation in vitro. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 400, 90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster GM, Venners SA, Mattman A, Martin JW, 2014. Associations between perfluoroalkyl acids (PFASs) and maternal thyroid hormones in early pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. Environ Res 133, 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, Zota AR, Schwartz JM, 2011. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the United States: NHANES 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives 119, 878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yolton K, Webster GM, Ye X, Calafat AM, Dietrich KN, Xu Y, Xie C, Braun JM, Lanphear BP, Chen A, 2018. Prenatal and childhood perfluoroalkyl substances exposures and children’s reading skills at ages 5 and 8years. Environ Int 111, 224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.