Abstract

The two major subtypes of bipolar disorder (BD), BD-I and BD-II, are distinguished based on the presence of manic or hypomanic episodes. Historically, BD-II was perceived as a less severe form of BD-I. Recent research has challenged this concept of a severity continuum. Studies in large samples of unrelated patients have described clinical and genetic differences between the subtypes. Besides an increased schizophrenia polygenic risk load in BD-I, these studies also observed an increased depression risk load in BD-II patients. The present study assessed whether such clinical and genetic differences are also found in BD patients from multiplex families, which exhibit reduced genetic and environmental heterogeneity. Comparing 252 BD-I and 75 BD-II patients from the Andalusian Bipolar Family (ABiF) study, the clinical course, symptoms during depressive and manic episodes, and psychiatric comorbidities were analyzed. Furthermore, polygenic risk scores (PRS) for BD, schizophrenia, and depression were assessed. BD-I patients not only suffered from more severe symptoms during manic episodes but also more frequently showed incapacity during depressive episodes. A higher BD PRS was significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Moreover, BD-I cases exhibited lower depression PRS. In line with a severity continuum from BD-II to BD-I, our results link BD-I to a more pronounced clinical presentation in both mania and depression and indicate that the polygenic risk load of BD predisposes to more severe disorder characteristics. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the genetic risk burden for depression also shapes disorder presentation and increases the likelihood of BD-II subtype development.

Subject terms: Bipolar disorder, Clinical genetics

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe, highly heritable mental disorder characterized by fluctuations in mood state and energy with recurring episodes of depression altering with episodes of mania or hypomania. Its early onset, chronicity, high prevalence (of approximately 1%), and lack of optimal treatment renders it one of the world’s most disabling conditions1. BD is etiologically heterogeneous, and the current diagnostic classification describes two major subtypes, BD type I (BD-I) and II (BD-II), which differ by the absence of full-blown manic episodes in BD-II. BD-I can be diagnosed based on a single manic episode, yet, in most cases, depressive episodes also occur. BD-II is diagnosed if at least one hypomanic and one depressive episode have occurred. Hypomanic episodes are, by definition, clinically less severe than manic ones, potentially have a shorter duration, are not characterized by a marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, and do not require hospitalization; the occurrence of any psychotic symptoms qualifies an episode as manic2.

Until recently, it was thought that both BD subtypes could be classified along a spectrum of the affective disorders defined by the extent and severity of mood elevation (i.e., major depressive disorder (MDD) < BD-II < BD-I). This concept is in line with findings of BD-I patients suffering from more psychotic3–6 and melancholic symptoms3, more hospitalizations6–8, and more severe and widespread impairment of cognitive functions9. It is also in line with the observation in several previous studies, that risk for either subtype of BD is higher for those with relatives affected by BD-I (compared to MDD and BD-II)2,10,11. However, this concept has been challenged by a series of studies which report a higher total number of episodes12–14, increased comorbidity with anxiety disorders8,13,14 and personality disorders8,15, as well as lower functioning15 and quality of life16 in BD-II compared to BD-I patients, although these findings were not consistent across studies7,8,17,18.

Recent large-scale formal and molecular genetic studies reported a higher heritability of BD-I than of BD-II11,19–21 and a high genetic correlation between BD-I and BD-II19–21. While the difference in heritability and the high genetic correlation between the subtypes may argue in favor of a severity continuum21, other findings instead point to partially distinct genetic etiologies of BD-I and BD-II. In contrast to other previous studies2,10,11, a large-scale Swedish registry-based family study found that relatives of BD patients showed the highest risk for the respective BD subtype: relatives of patients with BD-I had an increased risk for BD-I compared to BD-II and relatives of patients with BD-II had a trend for a higher risk for BD-II20. Different patterns of familial co-aggregation, genetic correlation, and polygenic risk score (PRS) analyses of both subtypes with other psychiatric disorders, in particular of BD-I with schizophrenia (SCZ) and of BD-II with MDD, underline potential molecular differences between the two subtypes11,19–24.

Clinical differences between BD-I and BD-II cases have rarely been studied in multiplex families with a high density of BD cases. An advantage of such multiplex families is the reduced genetic and environmental heterogeneity compared to unrelated case/control cohorts25. In a previous study on BD multiplex families, Frankland et al.26 described more mixed states in BD-II and more psychomotor retardation as well as more psychotic features of depressive episodes in BD-I cases. We have previously shown that, compared to unaffected family members and unrelated controls, BD patients from multiplex families have a high genetic risk load specifically for BD27,28. Furthermore, family members also had a higher genetic risk load for SCZ and, to a lesser degree, for MDD than unrelated controls28. Therefore, we hypothesize that a correlation between the genetic risk burden for psychiatric disorders and disease severity exists in these families.

The present study had three aims: first, to examine whether BD-I and BD-II patients from multiplex families with a high density of BD differ regarding their clinical course, the symptoms presenting during episodes, and psychiatric comorbidities. Second, to analyze whether the genetic risk burden for BD, SCZ, and MDD differed between the subtypes. Third, to investigate whether the PRS for BD, SCZ, and MDD were higher in patients showing more severe symptoms.

Materials and methods

Sample description

The study subjects are part of the Andalusian Bipolar Family (ABiF) study, which gathered data from 100 Spanish families with at least two cases of BD per family and has been described elsewhere29. In the present analyses, 327 BD patients from 98 families were included (BD-I n = 252, BD-II n = 75). The individual families were unrelated to each other, and the average pedigree contained 11.8 family members (SD = 7.6), including 3.3 (SD = 2.5) BD and 2.0 (SD = 2.2) MDD patients (Supplementary Table S1). Each family contained at least two BD patients. In addition, two pedigrees contained one schizophrenia patient each. The sample included 58.4% females and had an average age of 48.21 years (SD = 17.22; range=18–96; age refers to the age either at the interview or at the reported time of the patient’s death). The predominant level of education was primary school or less (70.6%) and was lower in patients with an earlier decade of birth. Diagnosis and clinical data were based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)30, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)31, the Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC)32, and on clinical records. The protocol of the structured diagnostic interview was modified to assess symptoms during lifetime episodes and not only those present in the most severe episode. Diagnoses were given by two trained clinicians using the best estimate approach. For 46 BD-I and 2 BD-II patients, no interview was available, and diagnoses were based on data assessed through best informants only. The local ethics committees of five Andalusian provinces approved the study (Comités de ética de la investigación provincial de Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Jaén, and Málaga), and all participants gave their written informed consent.

Genotyping and calculation of PRSs

Genetic information was available for 156 individuals (BD-I n = 115, BD-II n = 41) from 33 families. Genome-wide genotyping was carried out using the Illumina Infinium PsychArray BeadChip (PsychChip). All quality control (QC) and imputation procedures have been described previously28. In brief, QC and population substructure analyses were performed in PLINK v1.933, as described in the Supplementary Methods. The data were imputed to the 1000 Genomes phase 3 reference panel using SHAPEIT and IMPUTE234–36. The imputed dataset contained 8,628,089 variants.

For the calculation of PRSs37, SNP weights were estimated using the PRS-CS method38 with default parameters (see the Supplementary Methods). This method employs Bayesian regression to infer PRS weights while modeling the local linkage disequilibrium patterns of all SNPs using the EUR super-population of the 1000 Genomes reference panel, without requiring the calculation of several PRS using different p-value thresholds. The global shrinkage parameter φ was determined automatically (PRS-CS-auto; BD: φ = 1.22 × 10−4, MDD: φ = 1.26 × 10−4, BD: φ = 1.47 × 10−4). The PRSs were calculated, using these weights, in PLINK v1.90b6.13 on imputed dosage data33. As training data, we used summary statistics of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) containing 20,352 cases and 31,358 controls for BD19, 170,756 cases and 329,443 controls for MDD39, and 33,640 cases and 43,456 controls for SCZ40. As the ABiF cohort was part of the PGC BD GWAS19, Spanish samples were excluded from the BD training GWAS to avoid bias caused by sample overlap.

Generalized estimating equations

We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs), calculated using the package geepack41 in R v4.0.2, to analyze whether BD-I and BD-II differed regarding their demographic information, clinical course, symptoms presenting during episodes, and psychiatric comorbidities. GEEs are suitable for correlated data in samples with a family structure. An exchangeable correlation structure was selected, as is appropriate for the family structure of the sample. To allow for a stable fit, models were only calculated for variables that contained ≥10 individuals within each category (e.g., symptoms present and not present). For variables that did not meet this requirement, no test coefficients are provided in Tables 1–4. Secondary analyses including only probands with a personal interview are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of BD-I (n = 252) and BD-II (n = 75) patients.

| Variable | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48 (14) | 245 | 40 (13) | 75 | 0.024 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 |

| Gender (female) | 144 (57.14) | 252 | 47 (62.67) | 75 | 0.49 | 0.80 | 0.43–1.50 |

| Marital status (separated, divorced, or single) Reference: married or widowed | 73 (29.08) | 251 | 17 (22.67) | 75 | 0.31 | 1.40 | 0.73–2.69 |

| Educational level (secondary school or university degree) Reference: Primary or <4 years of school | 66 (26.19) | 252 | 29 (39.19) | 74 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.38–1.45 |

BD bipolar disorder, n valid sample size for the variable, OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval. Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance: α = 0.05/37 = 1.35 × 10−03.

Age refers to the age either at the interview or at the reported time of the patient’s death. Age and gender were used as independent variables, with BD type as the dependent variable. Marital status and educational levels were used as dependent variables, with BD type as the independent variable. We used the following covariates: marital status, sex; educational level, sex and decade of birth. The age is described by median and median absolute deviation, sample size (N) and percentage are provided for categorical variables.

Table 4.

Comparison of comorbidities between BD-I and BD-II patients.

| Comorbidity | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol abuse | 30 (11.90) | 252 | 5 (6.67) | 75 | 0.32 | 1.72 | 0.59–5.00 |

| Drug abuse | 15 (5.95) | 252 | 6 (8.00) | 75 | 0.87 | 1.09 | 0.38–3.13 |

| Alcohol dependence | 7 (2.78) | 252 | 3 (4.00) | 75 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.20–2.07 |

| Drug dependence | 3 (1.19) | 252 | 0 | 75 | |||

| Panic disorder | 6 (2.38) | 252 | 0 | 75 | |||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 2 (0.80) | 251 | 0 | 75 | |||

| Phobia | 2 (0.80) | 251 | 0 | 75 | |||

| Somatoform disorder | 2 (0.83) | 242 | 0 | 71 | |||

| Cyclothymic personality | 26 (10.32) | 252 | 7 (9.33) | 75 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.43–2.41 |

| Any comorbid disorder | 71 (28.17) | 252 | 17 (22.67) | 75 | 0.31 | 1.38 | 0.74–2.57 |

BD bipolar disorder, N valid sample size for the variable, OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval. Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance: α = 0.05/37 = 1.35 × 10−03.

BD type was the independent variable in all models. Sample size (N) and percentage are provided for categorical variables. To allow for a stable fit, models were only calculated for variables that contained ≥10 individuals per variable category. Variables without test coefficients (P, OR, CI) did not meet this requirement.

Sex and age were used as covariates in all analyses of non-sociodemographic, dichotomous variables. Only sex was used for quantitative clinical variables that already contained a temporal component. Quantitative variables were transformed using inverse rank-based normal transformation. The number of episodes and suicide attempts were divided by the illness duration before the transformation. Here, the illness duration is defined as the difference between the age and the age at BD onset. This ratio allowed for a better normalization than was observed when transforming the variables by themselves and adding the illness duration as a covariate to the model. Secondary analyses were conducted with illness duration as a covariate instead of dividing the numbers by the duration (Supplementary Table S3).

Correction for multiple testing

To establish an appropriate correction threshold for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni’s method, the number of independent tests reported in Tables 1–4 was estimated using principal component analysis (PCA) in R using the function prcomp. Of the 42 variables analyzed, the first 37 components jointly explained >99% (99.3%) of the phenotypic variance (Supplementary Fig. S1). We thus set the significance threshold to α = 0.05/37 = 1.35 × 10−03. We used a more liberal threshold to select variables for genetic analyses: the first nine components explained >50% (53.1%) of the phenotypic variance, corresponding to a significance threshold of α = 0.05/9 = 5.56 × 10−03.

Analyses of PRSs

PRS were analyzed to compare the polygenic risk burden for BD, MDD, and SCZ between BD types and to explore the influence of PRS on the clinical characteristics. We analyzed the association of PRS with all dichotomous phenotypes showing a p < 5.56 × 10−03 in GEE analyses (see above). PRS analyses were carried out as previously described28 in R using the function glmm.wald of the package GMMAT42, fitted by maximum likelihood using Nelder-Mead optimization. Family structure was modeled as a random effect, with a genetic relationship matrix calculated on pruned genotype data using GEMMA43.

PRSs were transformed by Z-score standardization before the analyses. Age and sex were used as fixed-effects covariates in all analyses. We used Bonferroni’s method to correct for three tests (α = 0.05/3 = 0.0167) in the analyses of PRS with BD type and for 18 tests (three PRS and six variables) in the analyses of PRS with clinical course and symptoms variables (α = 0.05/18 = 2.78 × 10−03). Based on a previous report19, we expected higher SCZ PRS in BD-I cases and higher MDD PRS in BD-II cases. Here, also one-sided p-values are reported.

Permutation analyses

All association p-values were validated using permutation analyses. Here, the null distribution of test statistics was empirically determined by repeating regression analyses with a random sampling of phenotype data. To calculate a p-value, the number of tests were counted where a model with a random association showed the same or a more extreme, i.e., smaller p-value than the correct, non-randomized model; this number was divided by the total number of tests. Results from these permutation analyses are, together with the respective number of permutations, presented in Supplementary Tables S3-S6. Some permutation p-values were higher than the p-values directly estimated with GEE models, but all variables that were significant in the primary GEE analyses showed a permutation p ≤ 2.66 × 10−03 (Supplementary Table S4). Typically, the permutation p-values of PRS analyses were lower than the p-values from GMMAT Wald tests (Supplementary Tables S5-S6).

Power analysis

We conducted power analyses for classical, p-value threshold-based PRS using AVENGEME44. Because PRS calculated by PRS-CS have a higher power45, we assume that these estimates constitute lower boundaries of our real statistical power. According to these analyses, we had a power of 0.64, 0.73, and 0.39 for analyses of BD-I vs. BD-II with PRS for BD, SCZ, and MDD, respectively (Supplementary Table S7). For the quantitative traits, the power was 0.91, 0.95, and 0.65 for BD, SCZ, and MDD, respectively.

Results

The sociodemographic variables did not differ significantly between family members diagnosed with BD-I and BD-II (Table 1). Among the variables related to the clinical course of disorder (Table 2), BD-I patients more frequently showed incapacity during depressive episodes (odds ratio (OR) = 2.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.47-4.28, p = 7.07 × 10−04) after Bonferroni correction for 37 independent tests (α = 1.35 × 10−03; 37 principal components explain 99.3% of the phenotypic variance). Furthermore, BD-I patients showed a longer average illness duration (β = 0.36 standard deviations, SE = 0.12, p = 2.83 × 10−03) and more hospitalizations during depressive episodes (OR = 6.41, CI = 1.93-21.35, p = 2.45 × 10−03), yet those two analyses did not withstand correction for multiple testing.

Table 2.

Differences in the clinical course between BD-I and BD-II patients.

| Variable | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | β | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first episode (years) | 21 (5) | 233 | 21 (6) | 75 | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Age at first manic episode (years) | 25 (7) | 230 | 26 (8) | 70 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Age at first depressive episode (years) | 22 (5.5) | 230 | 21 (6) | 75 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 23 (11) | 233 | 16 (9) | 75 | 2.83 × 10−03 | 0.36 | 0.12 |

| Duration of depressive episodes (weeks) | 16 (8) | 247 | 12 (8) | 75 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Number of depressive episodes/illness duration | 0.86 (0.57) | 229 | 0.78 (0.58) | 75 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Number of (hypo)manic episodes/illness duration | 0.52 (0.38) | 232 | 0.77 (0.65) | 75 | 0.029 | −0.35 | 0.16 |

| Number of suicide attempts/illness duration (median) | 0 (0) | 233 | 0 (0) | 75 | 0.046 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| Number of suicide attempts/illness duration (mean) | 0.04 (0.14) | 233 | 0.02 (0.08) | 75 | 0.046 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| Variable | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive polarity of the first episode | 102 (43.78) | 233 | 38 (50.7) | 75 | 0.22 | 0.75 | 0.48–1.18 |

| ECT during depressive episodes | 9 (3.64) | 247 | 1 (1.33) | 75 | 0.42 | 2.41 | 0.28–20.95 |

| Medication during depressive episodes | 237 (95.18) | 249 | 61 (81.33) | 75 | 0.010 | 3.93 | 1.38–11.20 |

| Hospitalization during depressive episodes | 50 (20.16) | 248 | 3 (4.00) | 75 | 2.45 × 10−03 | 6.41 | 1.93–21.35 |

| Incapacity during depressive episodes | 158 (69.30) | 228 | 33 (45.83) | 72 | 7.07 × 10−04 | 2.51 | 1.47–4.28 |

| Suicide attempted (ever) | 65 (25.79) | 252 | 11 (14.67) | 75 | 0.040 | 2.46 | 1.04–5.79 |

| Serious or extreme suicide attempt | 18 (7.14) | 252 | 2 (2.66) | 75 | 0.13 | 3.44 | 0.70–17.03 |

| Seasonality | 139 (58.65) | 237 | 36 (49.31) | 73 | 0.043 | 1.73 | 1.02–2.95 |

BD bipolar disorder, SE standard error, N sample size for the variable (before correction for covariates), OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, ECT electroconvulsive therapy. Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance: α = 0.05/37 = 1.35 × 10−03.

Quantitative variables were analyzed in linear, dichotomous variables in logistic models. BD type was the independent variable in all models. We used the following covariates: quantitative variables, sex; dichotomous variables, sex and age. All quantitative variables have been transformed for the analyses using inverse rank-based normalization to generate normally distributed residuals. The numbers of episodes and suicide attempts were divided by the illness duration before the transformation. See Supplementary Table S6 for analyses of these variables not divided by illness duration. All quantitative variables are described by median and median absolute deviation of untransformed variables, sample size (N) and percentage are provided for categorical variables. For the number of suicide attempts, mean and standard deviation are also provided. Significant variables are labeled in bold font.

During (hypo)manic episodes, BD-I patients exhibited significantly more inattention (OR = 4.79, CI = 1.93–11.88, p = 7.19 × 10−04; Table 3) and reckless behavior (OR = 13.48, CI = 6.68–27.20, p = 3.95 × 10−13). The p-value of reckless behavior was higher in the permutation analysis but remained significant (p = 1.26 × 10−04, Supplementary Table S4). During depressive episodes, suicidal ideation (OR = 2.51, CI = 1.34–4.70, p = 4.09 × 10−03) and delusions (OR = 4.80, CI = 1.67–13.78, p = 3.56 × 10−03) were observed more frequently in BD-I patients, but these associations were not significant after correction for multiple testing. BD-I and BD-II patients did not differ significantly regarding the examined comorbidities with other mental disorders (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of the symptoms profiles during lifetime between BD-I and BD-II patients.

| Symptoms during manic/hypomanic episodes | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperactivity | 252 (100) | 252 | 75 (100) | 75 | |||

| Talkativeness | 252 (100) | 252 | 73 (97.33) | 75 | |||

| Flight of idea | 236 (99.58) | 237 | 68 (97.14) | 70 | |||

| Inflated grandiosity | 248 (99.20) | 250 | 73 (97.33) | 75 | |||

| Decreased need for sleep | 251 (99.60) | 252 | 72 (96.00) | 75 | |||

| Inattention | 239 (95.60) | 250 | 64 (85.33) | 75 | 7.19 × 10−04 | 4.79 | 1.93–11.88 |

| Reckless behavior | 166 (66.13) | 251 | 9 (12.16) | 73 | 3.95 × 10−13 | 13.48 | 6.68–27.20 |

| Delusions | 217 (87.85) | 247 | 0 | 75 | |||

| Hallucinations | 20 (8.16) | 245 | 0 | 75 |

| Symptoms during depressive episodes | BD-I | N | BD-II | N | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appetite change | 240 (96.38) | 249 | 70 (93.33) | 75 | 0.25 | 1.80 | 0.66–4.94 |

| Loss of appetite or weight | 209 (90.87) | 230 | 67 (93.05) | 72 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.27–2.15 |

| Increased appetite or weight | 15 (6.52) | 230 | 5 (6.94) | 72 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.46–2.37 |

| Sleep change | 245 (98.39) | 249 | 73 (97.33) | 75 | |||

| Early morning awakening | 176 (79.64) | 221 | 48 (67.60) | 71 | 0.030 | 1.82 | 1.06–3.11 |

| Hypersomnia | 5 (2.16) | 231 | 2 (2.78) | 72 | |||

| Psychomotor alterations | 243 (97.59) | 249 | 72 (96.00) | 75 | |||

| Fatigue or tiredness | 248 (99.60) | 249 | 74 (98.67) | 75 | |||

| Diminished libido | 236 (97.52) | 242 | 71 (94.96) | 74 | |||

| Guilt | 215 (86.34) | 249 | 63 (84.00) | 75 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.36–2.91 |

| Difficult thinking or indecisiveness | 241 (96.79) | 249 | 72 (96.00) | 75 | 0.15 | 2.18 | 0.75–6.34 |

| Suicidal ideation | 222 (89.15) | 249 | 57 (72.00) | 75 | 4.09 × 10−03 | 2.51 | 1.34–4.70 |

| Loss of pleasure | 221 (95.26) | 232 | 69 (95.83) | 72 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.24–4.36 |

| Lack of reactivity | 149 (64.78) | 230 | 44 (61.11) | 72 | 0.81 | 1.07 | 0.63–1.80 |

| Different feeling of sadness | 206 (94.49) | 218 | 68 (94.44) | 72 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 0.32–3.72 |

| Morning worsening | 175 (76.75) | 228 | 46 (63.89) | 72 | 0.025 | 1.86 | 1.08–3.21 |

| Excessive guilt | 196 (84.48) | 232 | 59 (81.94) | 72 | 0.65 | 1.24 | 0.49–3.13 |

| Leaden paralysis | 103 (44.59) | 231 | 24 (33.33) | 72 | 0.05 | 1.81 | 1.00–3.27 |

| Delusions | 35 (14.11) | 248 | 3 (4.00) | 75 | 3.56 × 10−03 | 4.80 | 1.67–13.78 |

| Hallucinations | 28 (11.29) | 248 | 2 (2.67) | 75 | 0.021 | 5.57 | 1.29–24.04 |

BD bipolar disorder, n valid sample size for the variable, OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval. Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance: α = 0.05/37 = 1.35 × 10−03.

BD type was the independent variable in all models. Sample size (N) and percentage are provided for categorical variables. Significant variables are labeled in bold font. To allow for a stable fit, models were only calculated for variables that contained ≥10 individuals per variable category. Variables without test coefficients (P, OR, CI) did not meet this requirement.

When only analyzing patients with a personal interview, incapacity during depressive episodes and reckless behavior remained significant (Supplementary Table S2). In these secondary analyses, inattention did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing. By contrast, medication and hospitalization during depressive episodes, both only nominally significant in the primary analysis, were significant after correction for multiple testing in the secondary analysis.

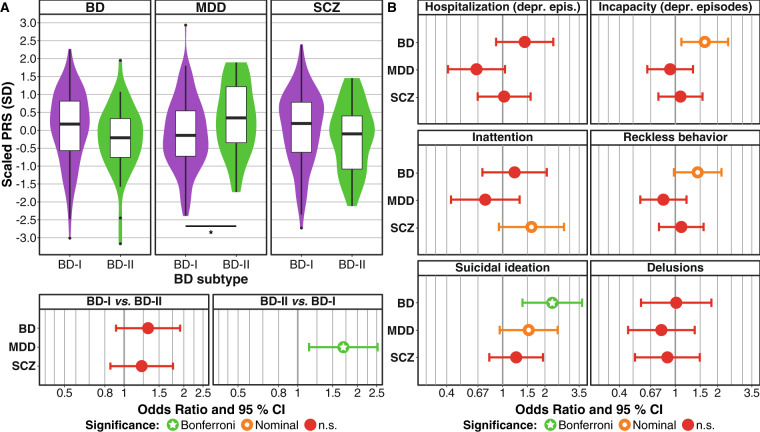

Next, we analyzed PRS in 156 of the 327 patients for which genetic data were available. In this smaller subset, the statistical power was reduced compared to the phenotype-level analyses (Supplementary Table S7). In our analysis whether PRS for BD19, MDD39, or SCZ40 differed between BD subtypes (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table S4), BD-II cases showed a significantly higher MDD risk burden after correction for three tests (OR = 1.70, CI = 1.14–2.53, p = 9.11 × 10−03, pone-sided = 4.55 × 10−03). No significant differences were observed for BD and SCZ PRS.

Fig. 1. Polygenic risk score analyses in a subset of 156 family members.

A BD-II patients showed a significantly higher MDD PRS than BD-I cases. SD standard deviation. Results from a logistic mixed regression model using PRS as predictors, BD type as the outcome, and sex and age as covariates (for full results see Supplementary Table S5). Comparisons significant after Bonferroni correction for three tests (α = 0.05/3 = 0.0167) are marked with an asterisk. For the SCZ PRS, the one-sided hypothesis was that BD-I cases have higher PRS; for the MDD PRS, the one-sided hypothesis was that BD-II cases show higher PRS. B Analysis of dichotomous clinical course and symptom variables with p < 5.56 × 10−03 in the phenotypic analyses (see Tables 2–3). Results from a logistic mixed regression model using PRS as predictors, symptoms as the outcome, and sex and age as covariates (for full results see Supplementary Table S6). Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance: α = 0.05/(6 × 3) = 2.78 × 10−03. For all PRS, the one-sided hypothesis was that the symptom severity increases with the PRS. PRS polygenic risk score, BD bipolar disorder, MDD major depressive disorder, SCZ schizophrenia, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, depr. epis. depressive episodes.

We finally analyzed whether PRS were higher in patients showing a more severe clinical course or more severe symptoms. We conducted these analyses for the six dichotomous variables differing between BD subtypes in primary analyses, prioritized using a p-value threshold of α = 5.56 × 10−03 (nine components explain 53.1% of the phenotypic variance). BD PRS were significantly higher in patients showing suicidal ideation after Bonferroni correction for 18 tests (OR = 2.25, CI = 1.38-3.67, p = 1.11 × 10−03, p1-sided = 5.53 × 10−04, Fig. 1B, Supplementary Table S5). Furthermore, BD PRS were higher in patients with incapacity during depressive episodes, yet this association did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing.

Discussion

The present study investigated phenotypic and genetic differences between BD-I and BD-II patients of BD multiplex families: First, patients diagnosed with BD-I showed both more severe manic episodes, with frequent inattention and reckless behavior, and more serious depressive episodes, which were often characterized by incapacity. Second, BD-II patients exhibited a significantly higher genetic MDD risk load than family members diagnosed with BD-I. Third, the genetic risk burden for BD was significantly associated with suicidal ideation.

It is not surprising that we found reckless behavior to be more frequent in BD-I than in BD-II cases, as it constitutes one of the main reasons for hospitalization. Previous studies have already described reckless behavior and inattention as features of BD-I14,46.

An increased incapacity of BD-I patients during depressive episodes was previously reported in a study conducted in unrelated BD patients7. Besides increased occupational impairment, further severity-related measures were described in this previous study, e.g., an increased need for medication and psychiatric hospitalizations, both of which only achieved nominal significance in the present study but were significant in our secondary analyses of patients with a personal interview. Furthermore, a tendency of BD-I patients to display more psychotic symptoms during their depressive episodes did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing in the present study. Previous findings regarding differences in the number of depressive episodes between BD-I and BD-II patients—not significant in the present study—were mixed: Studies in multiplex families found either no difference47 or more depressive episodes for BD-I26. Conversely, studies in unrelated patients in a clinical setting found more depressive episodes in BD-II patients12,13.

Berskon’s selection bias might have contributed to the observation of an increased severity and a higher number of depressive episodes in unrelated BD-II patients recruited from a clinical setting: It seems plausible that clinical samples of sporadic BD-II patients are enriched for patients suffering from more and more severe depressive episodes, for which they sought clinical help. Findings from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative (cross-sectional face-to-face interviews in 61,392 community-based adults from eleven countries)1 support this idea, finding that the severity of manic and depressive symptoms and of suicidal behavior increased monotonically from subthreshold BD to BD-II to BD-I.

Suicidal ideation was nominally associated with BD-I and can be considered a highly relevant indicator of mental disorder severity. Prior findings on the difference of suicidal ideations between BD-I and BD-II in samples of unrelated patients were inconsistent3,7,14. A large published epidemiological study investigating differences in suicidal ideation between the two subtypes in more than 1400 BD patients, found more suicidal ideation during depressive episodes in BD-I cases7. However, this difference was not observed in a previous study of multiplex families26. Published results are also mixed regarding lifetime suicide attempts8,14,48–52. A meta-analysis indicated possibly more suicide attempts in BD-I cases53, but this result was not significant (p = 0.07). Although suicide attempts occurred more frequently in BD-I than BD-II patients in the ABiF sample, this difference did not reach significance in the present study.

We have described previously that both affected and unaffected ABiF family members exhibit increased genetic risk loads for BD, MDD, and SCZ, compared to unaffected controls28. Within the families, BD patients showed higher BD PRS than unaffected family members28. In the present study, BD-II patients had a higher MDD risk load than BD-I patients, consistent with previous results from unrelated cases19. We observed a tendency for higher BD and SCZ PRS in BD-I patients, but both differences were not significant, possibly due to the small sample size, which impeded conclusive interpretations.

These findings do not unequivocally support the hypothesis that the BD genetic risk load shapes the development of either BD-II or BD-I along a severity continuum, i.e., that BDI cases carry more BD risk variants than BD-II cases. Instead, our previous28 and present results could suggest that, in the ABiF families, a general load of psychiatric, and especially BD, risk variants drive the overall BD vulnerability, while an increased MDD risk load may have shaped the family members’ BD presentation towards the BD-II subtype. The association of the BD PRS with suicidal ideation indicates that the polygenic makeup might, beyond its contribution to categorical subtypes of BD, shape the patients’ individual disorder manifestation on a symptom level. However, more studies with larger samples are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

There were several limitations of this study. We analyzed lifetime symptoms and not only symptoms during the worst episode, which should be kept in mind when interpreting and comparing the results to other studies. Furthermore, the small sample size, especially in the genetic analyses, limits the generalizability of results obtained and increases the likelihood of type II errors. Thus, these results need to be interpreted with caution. However, the family-based design and the homogeneity of the sample may have improved statistical power. Still, future studies in the ABiF study and other family cohorts should aim to analyze larger samples. Moreover, the present study only analyzed common genetic variants, and rare variants could also have contributed to clinical differences of BD patients in the ABiF multiplex families54,55. Accordingly, a notable disadvantage of studying multiplex families is that they may harbor more rare variants than patients recruited from the general population. In addition, their common variant patterns and shared environmental factors may differ from those observed in unrelated case/control samples. We analyzed a multi-generational study, and demographic factors, especially the educational system and the access to it, have changed during the 20th century in Spain. In earlier generations, the average educational level was lower, and more family members were married. The GWAS used for calculating the BD PRS contained over four times as many BD-I than BD-II cases19 and, therefore, the BD PRS was likely more sensitive for the genetic architecture of BD-I than for BD-II.

In summary, the present study compared clinical, symptomatological, and genetic features of BD-I and BD-II patients from BD multiplex pedigrees. The finding that BD-I patients showed more severe symptoms during their manic as well as during their depressive episodes, and the association of the BD PRS with suicidal ideation, are in line with a genetic severity continuum in multiplex BD families. The observation of a lower genetic risk load for MDD in BD-I patients, however, points to a more complex situation: It indicates that the individual polygenic risk load for different psychiatric disorders may influence the development of either BD-I or BD-II and the associated symptoms. Future studies should aim to replicate these results and examine the underlying mechanisms, e.g., biological pathways or potentially protective effects of high MDD PRS on the development of pronounced manic symptoms.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the Integrated Network IntegraMent under the auspices of the e:Med programme (grants 01ZX1314A to MMN and SC; 01ZX1314G and 01ZX1614G to MR), and through “AERIAL - Addiction: Early Recognition and Intervention Across the Lifespan” (grant 01EE1406C to MR), through “ASD-Net” (grant 01EE1409C to MR and SHW); by ERA-NET NEURON through “SynSchiz - Linking synaptic dysfunction to disease mechanisms in schizophrenia—a multilevel investigation“ (grant 01EW1810 to MR) and “EMBED” (grant 01EW1904); by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through “FOR2107” (grants RI908/11-2 to MR; NO246/10-2 to MMN and WI3439/3-2 to SHW); by the Andalusian regional Health and Innovation Government (grants PI-0060-2017, RC-0006-2015, and the Nicolas Monardes Programme to YDO (CTS-546)); and by the Swiss National Science Foundation (156791 to SC). MMN is a member of the DFG-funded cluster of excellence ImmunoSensation. TFMA was supported by the BMBF through the DIFUTURE consortium of the Medical Informatics Initiative Germany (grant 01ZZ1804A) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant MultipleMS, EU RIA 733161).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jose Guzman-Parra, Fabian Streit, Till F. M. Andlauer, Marcella Rietschel

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-01146-0).

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. 5h edn (DSM-5(TM)) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker G, et al. Differentiation of bipolar I and II disorders by examining for differences in severity of manic/hypomanic symptoms and the presence or absence of psychosis during that phase. J. Affect Disord. 2013;150:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brugue E, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, Cruz N, Vieta E. Depression subtypes in bipolar I and II disorders. Psychopathology. 2007;41:111–114. doi: 10.1159/000112026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goes FS, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altamura AC, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical characterization of patients with Bipolar Disorder I vs II: a Nationwide Italian Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018;268:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bega S, Schaffer A, Goldstein B, Levitt A. Differentiating between bipolar disorder types I and II: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions (NESARC) J. Affect Disord. 2012;138:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanti A. et al. Characteristics of bipolar I and II disorder: a study of 8766 individuals. Bipolar Disord.10.1111/bdi.12867 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cotrena C, et al. Executive functions and memory in bipolar disorders I and II: new insights from meta-analytic results. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020;141:110–130. doi: 10.1111/acps.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vieta E, Suppes T. Bipolar II disorder: arguments for and against a distinct diagnostic entity. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:163–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker GB, Romano M, Graham RK, Ricciardi T. Comparative familial aggregation of bipolar disorder in patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Australas. Psychiatry. 2018;26:414–416. doi: 10.1177/1039856218772249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vieta E, Gastó C, Otero A, Nieto E, Vallejo J. Differential features between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Compr. Psychiatry. 1997;38:98–101. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(97)90088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judd LL, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: A clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J. Affect Disord. 2003;73:19–32. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek JH, et al. Differences between bipolar i and bipolar II disorders in clinical features, comorbidity, and family history. J. Affect Disord. 2011;131:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinberg M, Mikkelsen RL, Kirkegaard T, Christensen EM, Kessing LV. Differences in clinical presentation between bipolar I and II disorders in the early stages of bipolar disorder: a naturalistic study. J. Affect Disord. 2017;208:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albert U, Rosso G, Maina G, Bogetto F. Impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity on quality of life in euthymic bipolar disorder patients: differences between bipolar I and II subtypes. J. Affect Disord. 2008;105:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forte A, et al. Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J. Affect Disord. 2015;178:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pallaskorpi S, et al. Five-year outcome of bipolar I and II disorders: findings of the Jorvi Bipolar Study. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:363–374. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stahl EA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:793–803. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song J, et al. Specificity in etiology of subtypes of bipolar disorder: evidence from a Swedish population-based family study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman, J. R. I. et al. The genetics of the mood disorder spectrum: genome-wide association analyses of more than 185,000 cases and 439,000 controls. Biol. Psychiatry10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.10.015 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Heun R, Maier W. The distinction of bipolar II disorder from bipolar I and recurrent unipolar depression: results of a controlled family study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1993;87:279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coryell W, Endicott J, Reich T, Andreasen N, Keller M. A family study of bipolar II disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1984;145:49–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.145.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endicott J, et al. Bipolar II. Combine or keep separate? J. Affect Disord. 1985;8:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ott J, Kamatani Y, Lathrop M. Family-based designs for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:465–474. doi: 10.1038/nrg2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankland A, et al. Comparing the phenomenology of depressive episodes in bipolar I and II disorder and major depressive disorder within bipolar disorder pedigrees. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2015;76:32–39. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins AL, et al. Identifying bipolar disorder susceptibility loci in a densely affected pedigree. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:1245–1246. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andlauer, T. F. M. et al. Bipolar multiplex families have an increased burden of common risk variants for psychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry10.1038/s41380-019-0558-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Guzman-Parra J, et al. The Andalusian Bipolar Family (ABiF) Study: protocol and sample description. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018;11:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. W. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders. Patient Ed (SCID-I/P, vs 20) (1994).

- 32.Mannuzza, S., Fyer, A. J. & Endicott, J. K. D. Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC) (New York Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York, 1985).

- 33.Chang CC, et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delaneau O, Zagury J-F, Marchini J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andlauer M, Nöthen MM. Polygenic scores for psychiatric disease: from research tool to clinical application. Medizinische Genet. 2020;32:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ge T, Chen CY, Ni Y, Feng YCA, Smoller JW. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–10.. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07882-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard DM, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ripke S, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J. Stat. Softw. 2006;15:1–11.. doi: 10.18637/jss.v015.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H, et al. Control for population structure and relatedness for binary traits in genetic association studies via logistic mixed models. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X, Stephens M. Efficient multivariate linear mixed model algorithms for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudbridge F. Power and predictive accuracy of polygenic risk scores. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:1003348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ni G. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of polygenic score methods across cohorts in psychiatric disorders. MedRxiv10.1101/2020.09.10.20192310 (2020).

- 46.Serretti A, Olgiati P. Profiles of ‘manic’ symptoms in bipolar I, bipolar II and major depressive disorders. J. Affect Disord. 2005;84:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fullerton JM, et al. Assessment of first and second degree relatives of individuals with bipolar disorder shows increased genetic risk scores in both affected relatives and young At-Risk Individuals. Am. J. Med. Genet. B: Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015;168:617–629. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tondo L, Lepri B, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risks among 2826 Sardinian major affective disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;116:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antypa N, Antonioli M, Serretti A. Clinical, psychological and environmental predictors of prospective suicide events in patients with Bipolar Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013;47:1800–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song JY, et al. Assessment of risk factors related to suicide attempts in patients with bipolar disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012;200:978–984. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182718a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goffin KC, et al. Different characteristics associated with suicide attempts among bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder patients. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016;76:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tidemalm, D., Haglund, A., Karanti, A., Landén, M. & Runeson, B. Attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: Risk factors in a cohort of 6086 patients. PLoS ONE9, e94097 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Novick DM, Swartz HA, Frank E. Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forstner A. J. et al. Whole-exome sequencing of 81 individuals from 27 multiply affected bipolar disorder families. Transl. Psychiatry10, 57 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Courtois E, et al. Contribution of common and rare damaging variants in familial forms of bipolar disorder and phenotypic outcome. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:124. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0783-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.