Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the infection risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with diabetes (according to treatment method).

Methods

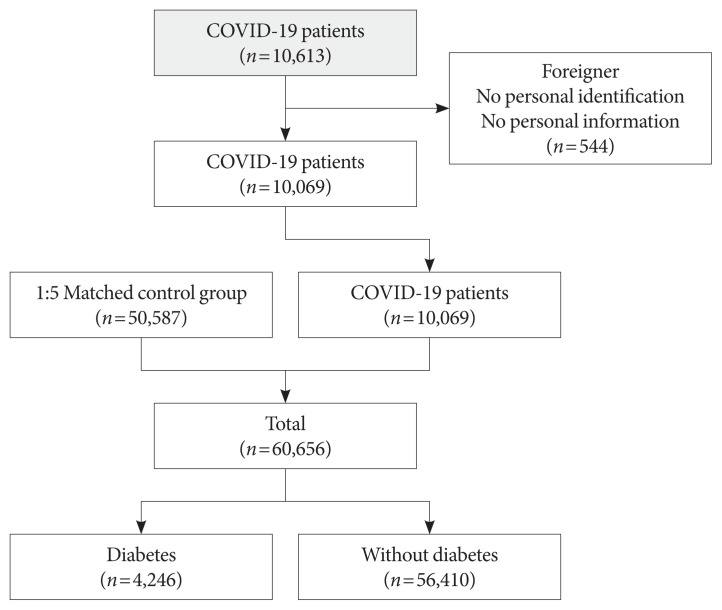

Claimed subjects to the Korean National Health Insurance claims database diagnosed with COVID-19 were included. Ten thousand sixty-nine patients with COVID-19 between January 28 and April 5, 2020, were included. Stratified random sampling of 1:5 was used to select the control group of COVID-19 patients. In total 50,587 subjects were selected as the control group. After deleting the missing values, 60,656 subjects were included.

Results

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) indicated that diabetic insulin users had a higher risk of COVID-19 than subjects without diabetes (OR, 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 1.53; P=0.0278). In the subgroup analysis, infection risk was higher among diabetes male insulin users (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.89), those between 40 and 59 years (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.44). The infection risk was higher in diabetic insulin users with 2 to 4 years of morbidity (OR, 1.744; 95% CI, 1.003 to 3.044).

Conclusion

Some diabetic patients with certain conditions would be associated with a higher risk of acquiring COVID-19, highlighting their need for special attention. Efforts are warranted to ensure that diabetic patients have minimal exposure to the virus. It is important to establish proactive care and screening tests for diabetic patients suspected with COVID-19 for timely disease diagnosis and management.

Keywords: COVID-19, Diabetes mellitus, Incidence

INTRODUCTION

Since the first report of a cluster of pneumonia that seemed similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in China in late 2019, over five million cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been reported worldwide by May 2020 [1]. COVID-19 outbreak that took place in Wuhan, China, has spread globally and posed a tremendous challenge to global healthcare facilities.

People with diabetes are at a higher risk of developing complications upon infection with a virus. A previous study showed that the prevalence of diabetes was 14.6% in H1N1 and 54.4% in Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) [2]. Diabetes, one of the most common comorbidities, has been correlated with high mortality and morbidity associated with COVID-19 [3,4]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have declared diabetes as one of the potential risk factors (CDC COVID-19 Response Team, 2020).

More than 425 million individuals are diabetic worldwide, and this number continuous to rise [5]. The prevalence of diabetes in adults was 10.1% in the United States. In Korea, diabetes prevalence is 14.4% among adults ≥30 years and 29.8% among those >65 years [6,7], indicating the need to focus on global and local health policies for diabetes [8]. Thus, it is imperative to develop effective strategies and define the risk of COVID-19 in diabetic individuals to reduce mortality.

It is believed that the risk of COVID-19 is high among diabetic patients, but there is no published study that show the high susceptibility of diabetic patients to COVID-19. In this direction, the present study aimed to determine COVID-19 rate in diabetic patients and compared it to that in the general population in Korea.

METHODS

Source of database

In this study, we used the data from the National Health Information (NHI) database 2015 to 2019 maintained by the NHI system, a government-affiliated agency under the Ministry of Health and Welfare that supervises all medical services in Korea [9]. The NHI is the only public medical insurance system in Korea and represents the entire Korean population because of the compulsory social insurance system. All clinics and hospitals in Korea submit data on in- and out-patients, including information on the diagnosis and medical costs, to the NHI to claim payments for patient care [9]. Others in the lowest income bracket are funded by taxes, including Medicaid coverage.

The database comprised information on four categories, including general information on specifications, consultation statements, diagnosis statements classified by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) [10], and detailed information about prescriptions [9]. The National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) contains information on patient demographics, medical use/transaction information, and deduction and claim database, as well as the insurers’ payment coverage [9]. We analysed the information for each individual with an unidentifiable code, including their age, gender, diagnosis, prescribed drugs, and pharmacy expenditures. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korean National Institute for Bioethics Policy (NHIMC 2020-03-084). Informed consent was exempted by the board.

Operational diagnosis of diabetes and anti-diabetic medications

Retrospective data for patients with diabetes were extracted from January 2019 through December 2019 using the Korean NHIS database. Individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were defined as those prescribed with anti-diabetic drugs with ICD-10 codes E11, E12, E13, or E14 as either principal diagnosis or 1st to 4th additional diagnosis at least once a year [11]. Anti-diabetic drugs dispensed in the pharmacy during the study period in Korea included nine classes (i.e., sulfonylurea [SU], biguanide, alpha-glucosidase inhibitor [AGI], thiazolidinedione [TZD], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor [DPP-4i], meglitinide, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor [SGLT2i], insulin, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist [GLP-1]) [11]. In the present study, we defined and enrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients prescribed with insulin for three or more with E10 ICD-10 code [7]. As the number patients with T1DM was too small (less than 40 in control group and nobody in COVID-19 group) to perform a separate investigation, we included them in “diabetes with insulin” group.

Detection of COVID-19 cases and control group

We identified COVID-19 cases based on the information available at the Korea Center for Disease Control & Prevention Center (KCDC). Patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 between January 28 and April 5. The case group comprised 10,069 diagnosed COVID-19 patients. Stratified random sampling was used to select a control group of COVID-19 patients. We performed 1:5 matching, and the control group was selected based on gender, age (0–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80 or more), and region (16 cities and provinces). Fig. 1 showed the study participants. In total, 50,587 subjects were selected as the control group; after deleting the missing values, the final number of subjects included in this study was 60,656.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram detailing participants. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Covariates

Age groups were categorised using 10-year intervals. Income groups were divided into 20 classes and re-classified into seven groups. Residential area was classified into three groups, namely, Seoul (capital city), metropolitan cities (Busan, Daegu, Incheon, Gwangju, Daejeon, and Ulsan), and rural areas. Information on anti-diabetic drugs such as metformin, SU, TZD, DPP-4i, AGI, meglitinide, SGLT2i, insulin, and GLP-1 was assessed from their claim records.

Statistical analysis

Subjects were classified into groups, with or without diabetes, and further subdivided into those on oral hypoglycaemic agent (OHA) or insulin use. We used descriptive statistics to investigate the data expressed as number and frequency percentage (%). The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) between two groups of interest were calculated using a multivariate logistic regression after adjustment for age, gender, income, living area, and comorbidity. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the COVID-19 patients and the control group. As the control group was selected using propensity score matching, characteristics such as gender, age, and living area were similar between two groups, with female patients predominating (COVID-19, 60.1%; control group, 60.1%). The proportion of those aged 20 to 29 years was higher than that of other age groups (COVID-19, 27.2%; control group, 26.9%), and about 77% lived in Daegu/Gyeongbuk. Among patients with COVID-19, 58.1% were infected from large gathering, 11.3% were infected in nursing facilities, 12.7% were infected by meeting with other COVID-19 patients, 8.8% were infected in other countries, and 9% by other methods. COVID-19 patients tended to have a lower socioeconomic status (SES). The low-income group accounted for a higher proportion of COVID-19 patients than the control group (COVID-19, low [self-employed] 8.4%, low [employee] 23.3%, medical-aid 7.9%; control group, low [self-employed] 7.3%, low [employee] 22.2%, medical-aid 3.7%). Among patients with COVID-19, 6% had diabetes and were taking OHA, and 1.4% had diabetes and received insulin injection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of people with COVID-19 and matched control subjects between January 28 and April 5

| Characteristic | Control subjects (n=50,587) | COVID-19 (n=10,069) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 20,178 (39.89) | 4,019 (39.9) | 0.9688 |

|

| |||

| Age, yr | 0.9779 | ||

| <20 | 3,572 (7.06) | 696 (6.9) | |

| 20–29 | 13,596 (26.9) | 2,737 (27.2) | |

| 30–39 | 5,252 (10.4) | 1,048 (10.4) | |

| 40–49 | 6,802 (13.5) | 1,348 (13.4) | |

| 50–59 | 9,256 (18.3) | 1,844 (18.3) | |

| 60–69 | 6,405 (12.7) | 1,283 (12.7) | |

| 70–79 | 3,355 (6.6) | 660 (6.55) | |

| ≥80 | 2,349 (4.64) | 453 (4.50) | |

|

| |||

| Region | 0.7285 | ||

| Metropolitan | 5,602 (11.1) | 1,094 (10.9) | |

| Rural area | 6,126 (12.1) | 1,188 (11.8) | |

| Daegu/Gyeongbuk | 38,859 (76.8) | 7,787 (77.4) | |

|

| |||

| Infection route | |||

| Others | NA | 912 (9.06) | - |

| Overseas | NA | 888 (8.82) | - |

| Contact with COVID-19 patients | NA | 1,276 (12.7) | - |

| Nursing facility | NA | 1,136 (11.3) | - |

| Large group gathering | NA | 5,857 (58.12) | - |

|

| |||

| Socioeconomic states | <0.0001 | ||

| Medical-aid | 1,849 (3.66) | 871 (7.93) | |

| Low (self-employed) | 3,703 (7.32) | 826 (8.37) | |

| Middle (self-employed) | 4,751 (9.39) | 938 (9.37) | |

| High (self-employed) | 5,016 (9.92) | 906 (8.74) | |

| Low (employee) | 11,208 (22.2) | 2,301 (23.3) | |

| Middle (employee) | 11,230 (22.2) | 1,851 (18.7) | |

| High (employee) | 12,830 (25.4) | 2,376 (23.6) | |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 9,584 (19.0) | 1,834 (18.21) | 0.0891 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,731 (3.42) | 344 (3.42) | 1.0000 |

| Heart failure | 895 (1.77) | 206 (2.05) | 0.0631 |

| Peripheral diseases | 2,585 (5.11) | 459 (4.56) | 0.0220 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2,473 (4.89) | 546 (5.42) | 0.0261 |

| Dementia | 1,019 (2.01) | 428 (4.25) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary diseases | 9,119 (18.0) | 1,951 (19.4) | 0.0014 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 446 (0.88) | 101 (1.00) | 0.2630 |

| Asthma | 4,011 (7.93) | 860 (8.54) | 0.0409 |

| Connective tissue | 1,096 (2.17) | 225 (2.23) | 0.6968 |

| Liver diseases | 250 (0.49) | 58 (0.58) | 0.3280 |

| Hemiplegia | 168 (0.33) | 99 (0.98) | <0.0001 |

| Renal diseases | 868 (1.72) | 163 (1.62) | 0.5185 |

| Cancer | 1,940 (3.83) | 373 (3.70) | 0.5511 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1,894 (3.74) | 394 (3.91) | 0.4330 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 0.0120 | ||

| No | 47,081 (93.1) | 9,329 (92.7) | |

| OHA only | 2,986 (5.90) | 603 (5.99) | |

| Insulin±OHA | 520 (1.03) | 137 (1.36) | |

Values are presented as number (%).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NA, not applicable; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent.

COVID-19 incidence in diabetic subjects

This study included 4,246 patients with diabetes and 56,410 without diabetes; their demographics, including age, sex, income, living area, current anti-diabetic treatment, and duration of diabetes, are presented in Table 2. In total, 45.2% and 39.5% of subjects from the diabetic and non-diabetic groups were male, respectively. Compared to with the subjects without diabetes, those with diabetes tended to be older (diabetes mellitus [DM], 40+: 97%; without DM, 40+: 52.5%) and lived in Daegu/Gyeongbuk (DM 81.7%; without DM 76.5%). Among subjects with diabetes, 77% had a morbidity of 5 years or more, 19.7% had a morbidity of 2 to 4 years, and 3.3% had a morbidity of 1 year or less. In total, 15.5% diabetic patients were treated with insulin. Among patients with diabetes, a greater portion of patients who were infected with COVID-19 in nursing facilities or by meeting with COVID-19 patients than the ones without diabetes (DM, large group gathering 32.3%, nursing facility 26%, meeting with COVID-19 patients 20%, overseas 2.4%, others 19.3%; without DM, large group gathering 60.2%, nursing facility 10.1%, meeting with COVID-19 patients 12.1%, overseas 9.3%, others 8.2%). COVID-19 patients with diabetes also had more comorbid dementia, and hemiplegia (COVID-19 patients with DM, dementia 12.6%, hemiplegia 2.2%; COVID-19 patients without DM, dementia 3.6%, hemiplegia 0.9%).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of people with COVID-19 and matched control subjects by diabetes

| Characteristic | Non-DM (n=56,410) | DM with OHA (n=3,589) | DM with insulin (n=657) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Control (n=47,081) | COVID-19 (n=9,329) | P value | Control (n=2,986) | COVID-19 (n=603) | P value | Control (n=520) | COVID-19 (n=137) | P value | |

| Male sex | 18,601 (39.51) | 3,677 (39.41) | 0.8747 | 1,345 (45.04) | 272 (45.11) | 0.8747 | 232 (44.62) | 70 (51.09) | 0.2086 |

|

| |||||||||

| Age, yr | 0.9622 | 0.5665 | 0.2474 | ||||||

| <20 | 3,568 (7.58) | 695 (7.45) | 2 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.38) | 1 (0.73) | |||

| 20–29 | 13,555 (28.79) | 2,732 (29.29) | 26 (0.87) | 3 (0.50) | 15 (2.88) | 2 (1.46) | |||

| 30–39 | 5,188 (11.02) | 1,039 (11.14) | 47 (1.57) | 8 (1.33) | 17 (3.27) | 1 (0.73) | |||

| 40–49 | 6,598 (14.01) | 1,300 (13.94) | 181 (6.06) | 40 (6.63) | 23 (4.42) | 8 (5.84) | |||

| 50–59 | 8,461 (17.97) | 1,665 (17.85) | 713 (23.88) | 147 (24.38) | 82 (15.77) | 32 (23.36) | |||

| 60–69 | 5,324 (11.31) | 1,057 (11.33) | 919 (30.78) | 189 (31.34) | 162 (31.15) | 37 (27.01) | |||

| 70–79 | 2,531 (5.38) | 479 (5.13) | 701 (23.48) | 153 (25.37) | 123 (23.65) | 28 (20.44) | |||

| ≥80 | 1,856 (3.94) | 362 (3.88) | 397 (13.30) | 63 (10.45) | 96 (18.46) | 28 (20.44) | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Region | 0.8639 | 0.0339 | 0.5518 | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 5,319 (11.30) | 1,053 (11.29) | 246 (8.24) | 34 (5.64) | 37 (7.12) | 7 (5.11) | |||

| Rural area | 5,740 (12.19) | 1,119 (11.99) | 327 (10.95) | 56 (9.29) | 59 (11.35) | 13 (9.49) | |||

| Daegu/Gyeongbuk | 36,022 (76.51) | 7,157 (76.72) | 2,413 (80.81) | 513 (85.07) | 424 (81.54) | 117 (85.4) | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Infection route | |||||||||

| Others | NA | 769 (8.24) | - | NA | 120 (19.90) | - | NA | 23 (16.79) | - |

| Overseas | NA | 870 (9.33) | - | NA | 14 (2.32) | - | NA | 4 (2.92) | - |

| Contact with COVID-19 patients | NA | 1,128 (12.09) | - | NA | 135 (22.39) | - | NA | 13 (9.49) | - |

| Nursing facility | NA | 944 (10.12) | - | NA | 127 (21.06) | - | NA | 65 (47.45) | - |

| Religious/other gathering | NA | 5,618 (60.22) | - | NA | 207 (34.33) | - | NA | 32 (23.36) | - |

|

| |||||||||

| Income | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Medical-aid | 1,534 (3.26) | 740 (7.93) | 267 (8.94) | 95 (15.75) | 48 (9.23) | 36 (26.28) | |||

| Low (self employed) | 3,456 (7.34) | 781 (8.37) | 198 (6.63) | 34 (5.64) | 49 (9.42) | 11 (8.03) | |||

| Middle(self employed) | 4,395 (9.33) | 874 (9.37) | 317 (10.62) | 57 (9.45) | 39 (7.50) | 7 (5.11) | |||

| High (self employed) | 4,628 (9.83) | 815 (8.74) | 334 (11.19) | 72 (11.94) | 54 (10.38) | 19 (13.87) | |||

| Low (employee) | 10,574 (22.46) | 2,173 (23.29) | 545 (18.25) | 113 (18.74) | 89 (17.12) | 15 (10.95) | |||

| Middle (employee) | 10,621 (22.56) | 1,746 (18.72) | 526 (17.62) | 89 (14.76) | 83 (15.96) | 16 (11.68) | |||

| High (employee) | 11,873 (25.22) | 2,200 (23.58) | 799 (26.76) | 143 (23.71) | 158 (30.38) | 33 (24.09) | |||

|

| |||||||||

| DM duration | 0.1833 | 0.2759 | |||||||

| 5 years or more | NA | NA | - | 2,259 (75.65) | 438 (72.64) | 457 (87.88) | 117 (85.40) | ||

| 1–4 years | NA | NA | - | 623 (20.86) | 146 (24.21) | 48 (9.23) | 18 (13.14) | ||

| 1 year or less | NA | NA | - | 104 (3.48) | 19 (3.15) | 15 (2.88) | 2 (1.46) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Current DM medication | |||||||||

| aGI | NA | NA | - | 52 (1.74) | 15 (2.49) | 0.2847 | 23 (4.42) | 5 (3.65) | 0.8721 |

| DPP-4i | NA | NA | - | 1,945 (65.14) | 399 (66.17) | 0.6609 | 378 (72.69) | 101 (73.72) | 0.8939 |

| GLP-1 | NA | NA | - | 16 (0.54) | 3 (0.50) | 1.0000 | 18 (3.46) | 7 (5.11) | 0.5183 |

| Metformin | NA | NA | - | 2,673 (89.52) | 545 (90.38) | 0.5741 | 430 (82.69) | 107 (78.10) | 0.2658 |

| Glinide | NA | NA | - | 7 (0.23) | 2 (0.33) | 0.6526 | 5 (0.96) | 0 (0.00) | 0.5893 |

| SU | NA | NA | - | 1,301 (43.57) | 240 (39.80) | 0.0968 | 224 (43.08) | 75 (54.74) | 0.0191 |

| SGLT2i | NA | NA | - | 246 (8.24) | 48 (7.96) | 0.8840 | 64 (12.31) | 12 (8.76) | 0.3148 |

| TZD | NA | NA | - | 365 (12.22) | 71 (11.77) | 0.8106 | 64 (12.31) | 15 (10.95) | 0.7738 |

| Insulin | NA | NA | - | NA | NA | - | 520 (100) | 137 (100) | - |

|

| |||||||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 7,258 (15.42) | 1,355 (14.52) | 0.0299 | 1,970 (65.97) | 391 (64.84) | 0.6260 | 356 (68.46) | 88 (64.23) | 0.4020 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,260 (2.68) | 237 (2.54) | 0.4776 | 369 (12.36) | 86 (14.26) | 0.2244 | 102 (19.62) | 21 (15.33) | 0.3071 |

| Heart failure | 656 (1.39) | 152 (1.63) | 0.0882 | 175 (5.86) | 45 (7.46) | 0.1607 | 64 (12.31) | 9 (6.57) | 0.0804 |

| Peripheral diseases | 2,018 (4.29) | 360 (3.86) | 0.0646 | 464 (15.54) | 80 (13.27) | 0.1748 | 103 (19.81) | 19 (13.87) | 0.1424 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1,893 (4.02) | 392 (4.20) | 0.4340 | 451 (15.10) | 116 (19.24) | 0.0132 | 129 (24.81) | 38 (27.74) | 0.5550 |

| Dementia | 777 (1.65) | 335 (3.59) | <0.0001 | 191 (6.40) | 63 (10.45) | 0.0006 | 51 (9.81) | 30 (21.9) | 0.0002 |

| Pulmonary diseases | 8,242 (17.51) | 1,768 (18.95) | 0.0009 | 717 (24.01) | 148 (24.54) | 0.8209 | 160 (30.77) | 35 (25.55) | 0.2779 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 375 (0.80) | 84 (0.90) | 0.3382 | 47 (1.57) | 12 (1.99) | 0.5773 | 24 (4.62) | 5 (3.65) | 0.7981 |

| Asthma | 3,634 (7.72) | 782 (8.38) | 0.0308 | 320 (10.72) | 66 (10.95) | 0.9257 | 57 (10.96) | 12 (8.76) | 0.5542 |

| Connective tissue | 983 (2.09) | 194 (2.08) | 0.9905 | 93 (3.11) | 26 (4.31) | 0.1697 | 20 (3.85) | 5 (3.65) | 1.0000 |

| Liver diseases | 185 (0.39) | 40 (0.43) | 0.6805 | 44 (1.47) | 11 (1.82) | 0.6472 | 21 (4.04) | 7 (5.11) | 0.7532 |

| Hemiplegia | 138 (0.29) | 83 (0.89) | <0.0001 | 18 (0.60) | 7 (1.16) | 0.2170 | 12 (2.31) | 9 (6.57) | 0.0239 |

| Renal diseases | 606 (1.29) | 104 (1.11) | 0.1891 | 199 (6.66) | 37 (6.14) | 0.6984 | 63 (12.12) | 22 (16.06) | 0.2800 |

| Cancer | 1,672 (3.55) | 311 (3.33) | 0.3115 | 194 (6.50) | 44 (7.30) | 0.5285 | 74 (14.23) | 18 (13.14) | 0.8498 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1,657 (3.52) | 338 (3.62) | 0.6423 | 201 (6.73) | 46 (7.63) | 0.4805 | 36 (6.92) | 10 (7.30) | 1.0000 |

Values are presented as number (%).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DM, diabetes mellitus; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent; NA, not applicable; aGI, alpha-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; SU, sulfonylurea; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

COVID-19 risk in diabetic patients as compared to the general population

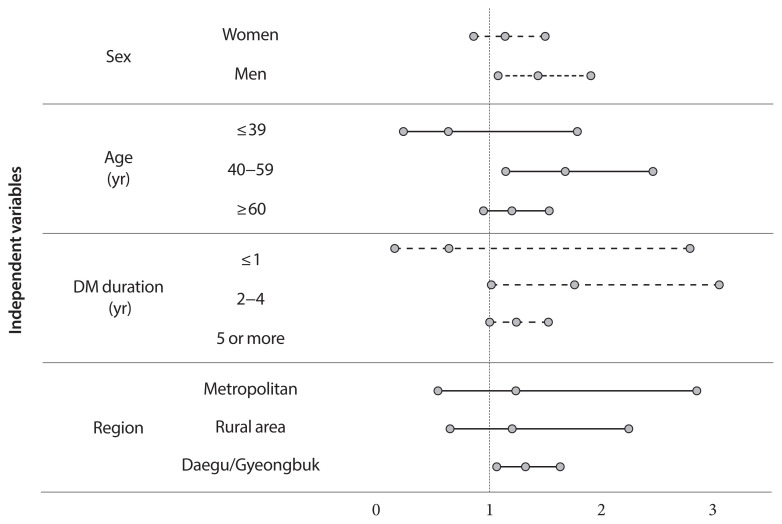

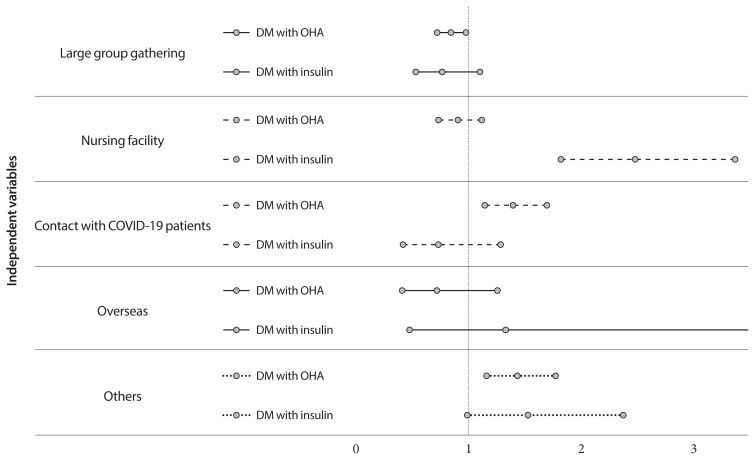

While calculating ORs based on the occurrence of diabetes, the adjusted OR showed that diabetic insulin users had a higher risk of COVID-19 than subjects without diabetes (diabetes with OHA [OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.13; P=0.5841], diabetes with insulin [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03 to 01.53; P=0.0278]) (Table 3). We divided patients into two groups (diabetes and without diabetes), and those with diabetes tended to have a slightly higher risk of COVID-19, but no statistical significance was observed (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.16; P=0.1999). In addition, subjects with lower income had a higher risk of getting COVID-19 ([low, employee: OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.17; P=0.0058], [low, self-employed: OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.29; P=0.0002], [medical-aid: OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.23 to 2.70; P< 0.0001]). Patients with comorbidities such as dementia, pulmonary diseases, and hemiplegia were more likely to have COVID-19 ([dementia: OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 2.15 to 2.86; P<0.0001], [pulmonary disease: OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.16; P=0.0268], [hemiplegia: OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.83 to 3.15; P<0.0001]). In the subgroup analysis, the risk of infection among diabetic patients on insulin was higher in males (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.89), those between 40 and 59 years of age (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.44) compared to the control group (non-DM). Furthermore, the risk of infection among diabetic insulin users was higher when the morbidity of diabetes was between 2 and 4 years (OR, 1.744; 95% CI, 1.003 to 3.044) after adjusting for age, sex, duration of diabetes, infection route, region, SES, and medications. The risk of diabetic insulin users in Daegu/Gyeongbuk provinces was high (OR, 1.303; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.618), as could be expected from the special COVID-19 transmission situation in Korea of in early 2020 (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 shows that insulin users in nursing facilities had a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 than the control group (non-DM) when we classified diabetic patients as those with oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin users according to their current treatment status.

Table 3.

Mutually adjusted infection rates during 28th January to 5th April 2020 among people with diabetes versus matched control subjects

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women | 0.991 | 0.947–1.037 | 0.6918 |

| Men | 1.000 | - | - |

|

| |||

| Age, yr | |||

| <20 | 1.469 | 1.257–1.718 | <0.0001 |

| 20–29 | 1.553 | 1.351–1.785 | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 1.578 | 1.361–1.831 | <0.0001 |

| 40–49 | 1.514 | 1.313–1.747 | <0.0001 |

| 50–59 | 1.504 | 1.312–1.724 | <0.0001 |

| 60–69 | 1.498 | 1.307–1.717 | <0.0001 |

| 70–79 | 1.329 | 1.153–1.531 | <0.0001 |

| ≥80 | 1.000 | - | - |

|

| |||

| Region | |||

| Metropolitan | 1.000 | - | - |

| Rural area | 0.999 | 0.913–1.094 | 0.8730 |

| Daegu/Gyeongbuk | 0.994 | 0.927–1.067 | 0.9888 |

|

| |||

| Current diabetes medication | |||

| Control | 1.000 | - | - |

| OHA only | 1.028 | 0.932–1.134 | 0.5841 |

| Insulin±OHA | 1.250 | 1.025–1.525 | 0.0278 |

|

| |||

| Socioeconomic states | |||

| Medical-aid | 2.454 | 2.234–2.695 | <0.0001 |

| Low (self-employed) | 1.180 | 1.081–1.288 | 0.0002 |

| Middle (self-employed) | 1.060 | 0.975–1.152 | 0.1703 |

| High (self-employed) | 0.977 | 0.899–1.063 | 0.5946 |

| Low (employee) | 1.094 | 1.026–1.166 | 0.0058 |

| Middle (employee) | 0.877 | 0.820–0.937 | 0.0001 |

| High (employee) | 1.000 | - | - |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities (reference: without disease) | |||

| Hypertension | 0.912 | 0.850–0.979 | 0.0113 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.979 | 0.860–1.115 | 0.7503 |

| Heart failure | 1.153 | 0.976–1.362 | 0.0937 |

| Peripheral diseases | 0.875 | 0.786–0.974 | 0.0145 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 0.892 | 0.798–0.997 | 0.0439 |

| Dementia | 2.481 | 2.152–2.860 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary diseases | 1.084 | 1.009–1.164 | 0.0268 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.033 | 0.821–1.299 | 0.7829 |

| Asthma | 1.014 | 0.918–1.121 | 0.7801 |

| Connective tissue | 1.013 | 0.874–1.175 | 0.8614 |

| Liver diseases | 1.006 | 0.748–1.353 | 0.9698 |

| Hemiplegia | 2.400 | 1.830–3.148 | <0.0001 |

| Renal diseases | 0.898 | 0.754–1.069 | 0.2281 |

| Cancer | 0.967 | 0.860–1.087 | 0.5726 |

| hypothyroidism | 1.016 | 0.906–1.139 | 0.7852 |

The odds ratios were adjusted for age, sex, region, medications, co-morbidities, and socioeconomic status.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agents.

Fig. 2.

Infection risk of coronavirus disease 2019 in diabetes with their specific conditions compared to matched control subjects without diabetes. DM, diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 3.

Infection risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) according to infection route in diabetes compared to matched control subjects without diabetes. DM, diabetes mellitus; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the risks of contracting COVID-19 in diabetic and non-diabetic patients in Korea using a nationwide, population-based database. We divided subjects into three groups (without diabetes, diabetes with OHA, and diabetes with insulin) and found that diabetic patients with certain conditions could have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19. This association was stronger in males than in females, among individuals between 40 and 59 years of age, and in those with a diabetes morbidity of 2 to 4 years. Given the special situation in the Republic of Korea, where infection spread rapidly in the Daegu/Gyeongbuk region, we divided the region into three groups (metropolitan, rural, Daegu/Gyeongbuk) and investigated the risk of contracting COVID-19 in diabetic patients. We found that the association between diabetic insulin users and COVID-19 was stronger in the Daegu/Gyeongbuk region than in any other region.

Some different from previous two experiences of coronavirus infections, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, the infection risk of COVID-19 in Korea was found to be higher in diabetic patients with certain conditions than in the general population. In two meta-analyses on MERS-CoV patients, the prevalence of diabetes was 54% and 51%, which was higher than that of any other comorbidities, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and obesity [2,12]. The increased susceptibility of diabetic patients with some specific conditions to COVID-19 observed in our study is similar to that observed in previous studies which also showed high proportions [2,13] of diabetic individuals among coronavirus-infected patients.

The idea that subjects with diabetes are more susceptible to certain infections than the general population is widely accepted [14]. Indeed several studies have reported that diabetic patients have a higher risk than the general population almost all infections [15,16]. Diabetic patients have a 2.6, 3.3, and 3.7 times higher incidences of pneumonia, influenza, and bronchitis than non-diabetic adults, respectively [15–17]. The association between diabetes and infection has been linked to several causal pathways, including impaired immune responses within the hyperglycemic environment [18]. Patients with diabetes exhibit impaired phagocytosis by neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes, decreased neutrophil chemotaxis and bactericidal activity, and dysregulated innate cell-mediated immunity. The high glucose concentration in the superficial epithelial tissue of these patients may increase their susceptibility to colonization by infectious agents [16].

One in vivo study reported relatively low levels of inflammatory cytokines, as well as fewer macrophages and T cells in diabetic mice in response to infection than in control mice. Moreover, T2DM is associated with low-grade chronic inflammation induced by excessive visceral adipose tissue [19]. This inflammatory status affects homeostatic glucose regulation and peripheral insulin sensitivity. Chronic hyperglycemia and inflammation can induce an abnormal and ineffective immune response. This complex and multifactorial pathway is related to impairment in multiple steps of the immune system, including chemotaxis, phagocytic activity, and cytokine activity [20].

Our data demonstrate that the risk of COVID-19 is higher in subjects treated with insulin than in those on OHA, especially in the 2nd to 4th year after diagnosis. Insulin is known as the safest therapy and the traditional first-choice drug during pregnancy and perinatal care. Insulin therapy is recommended during acute or critical illness, given the increase in insulin resistance and demand under such conditions. However, in Korea, oral medications are preferred for diabetes treatment, and insulin prescription rate is lower than that in other countries. Insulin is often used as the last treatment option, although its use has greatly increased by 4% to 19% in recent years [21,22]. The patient group treated with insulin within 2 to 4 years of diabetes diagnosis may be deemed susceptible to infection. Our findings suggest that such patients are vulnerable to COVID-19, because they have a condition that requires insulin treatment within a relatively short period of time from diabetes diagnosis.

SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets by close contact between people [23]. It is believed that the risk of infection is high in subjects with comorbidities such as dementia or paralysis because they often live in nursing facilities. In addition, low SES is strongly associated with high susceptibility to COVID-19 because such individuals reside in denser places, which increases the frequency of contact [24].

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), which emerged in China, has been rapidly spreading to many countries, and has many similarities with SARS-CoV [25]; however, COVID-19 spread more rapidly in a higher number of people than SARS-CoV. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks in patients with diabetes to guide interventions and prevention strategies. Here, we show the high risk of COVID-19 in diabetic patients, which accounts for a large proportion of the world. We believe that our study provides fundamental knowledge, which would help to establish preventive measures. We included a large proportion of patients in their 20s and 30s. It is meaningful to assess the actual risk of COVID-19 in diabetic patients upon exposure to SARS-CoV-2 because younger patients are in an overall healthier state than the elderly population.

Our study shows that peoples of low SES covered by Medical-aid are at high risk of COVID-19. Because of their economic disadvantages, they are more likely to live in overcrowded housing or accommodation and to have poorer housing conditions, which are all risk factors for lower respiratory tract infections. Those in low SES groups are more likely to be employed in occupations without opportunities to work from home and have unstable incomes and work conditions which may leave these people more vulnerable to COVID-19 [26]. We should be aware that financially struggling people are particularly vulnerable to infection and pay attention to reducing their risk.

This study has some limitations. First, the data used in our study were based on national health insurance claims. Therefore, clinical information such as the blood sugar control state in diabetic patients was not available. Second, this study could not consider diabetes duration and treatment for those who had a morbidity of more than 5 years because the data used were acquired from January 2015. Third, we were unable to investigate the severity and course of treatment in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 owing to the lack of data after COVID-19 diagnosis; only treatment outcome, whether the patient was discharged or died, was available. Since a causal relationship between some comorbidities and lower risk of COVID-19 could not be proven in logistic regression analysis, we need to be careful when interpreting the results.

Despite these limitations, our study has many strengths. First, this is the first study to compare the risk of COVID-19 in subjects with or without diabetes using the data of all confirmed cases and matched control group. Most of the existing data are limited to the proportion of diabetes only in infected people, resulting in an approximately 10% prevalence of diabetes in most studies. Therefore, the risk of COVID-19 among patients with diabetes could not be evaluated. Our study shows a higher risk of COVID-19 in diabetic patients with some specific conditions, compared to the general population. Second, this study separately analyzed Daegu/Gyeongbuk, which had an especially bad situation of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Korea. The novel coronavirus rapidly spread in the Daegu/Gyeongbuk region. Therefore, it was possible to estimate the effect on diabetes patients if the virus could rapidly spread in a small area over a short period of time and to measure the risk of infection. Third, the relationship between diabetes and COVID-19 was investigated from various perspectives. This study examined several risk factors such as treatment method (insulin or OHA only) and age from the national patient-level data. Lastly, we were able to adjust for comorbidities, SES, and many other confounders using historical data.

Our study identified that some diabetic patients with certain conditions would be more susceptible to COVID-19 than the general population. The risk is high among middle-aged subjects prescribed insulin treatment within 2 to 4 years after diabetes diagnosis. Patients with diabetes could be the most vulnerable population in the COVID-19 pandemic. As the complications and mortality rate associated with diabetes have significantly decreased over the past 20 years, the life expectancy of diabetic patients has increased [17]. Given the high prevalence and rapid increase in diabetes cases worldwide, additional attention is required for these patients. Efforts are warranted to ensure that diabetic patients with some specific conditions have minimal exposure to the virus. It is important to establish proactive care and screening tests for diabetic patients suspected with COVID-19 for timely disease diagnosis and management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

National Health Information Database was provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and Korea Center for Disease Control & Prevention Center (KCDC). The authors would like to thank the NHIS and KCDC for their cooperation. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (NHIMC-2020C-R007). The funding source was not involved in oversight or design of the study, in the analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception or design: S.Y.C., D.W.K., S.O.S.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: S.Y.C., D.W.K., S.A.L., S.J.L., J.H.C., Y.J.C., S.W.K., S.O.S.

Drafting the work or revising: S.Y.C., S.O.S.

Final approval of the manuscript: S.Y.C., S.O.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus: China. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/(cited 2020 Dec 1)

- 2.Badawi A, Ryoo SG. Prevalence of diabetes in the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health Res. 2016;5:733. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2016.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BY, Won JC, Lee JH, Kim HS, Park JH, Ha KH, Won KC, Kim DJ, Park KS. Diabetes fact sheets in Korea, 2018: an appraisal of current status. Diabetes Metab J. 2019;43:487–94. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2019.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song SO, Song YD, Nam JY, Park KH, Yoon JH, Son KM, Ko Y, Lim DH. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes mellitus in Korea through an investigation of the national registration project of type 1 diabetes for the reimbursement of glucometer strips with additional analyses using claims data. Diabetes Metab J. 2016;40:35–45. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB, Satija A, Manson JE. Curbing the diabetes pandemic: the need for global policy solutions. JAMA. 2015;313:2319–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song SO, Jung CH, Song YD, Park CY, Kwon HS, Cha BS, Park JY, Lee KU, Ko KS, Lee BW. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:395–403. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percy C, Fritz A, Jack A, Shanmugarathan K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, Whelan S. International classification of diseases for oncology. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko SH, Kim DJ, Park JH, Park CY, Jung CH, Kwon HS, Park JY, Song KH, Han K, Lee KU, Ko KS Task Force Team for Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Trends of antidiabetic drug use in adult type 2 diabetes in Korea in 2002–2013: nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4018. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badawi A, Ryoo SG. Prevalence of comorbidities in the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;49:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, Ji R, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhou Y. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey IM, Critchley JA, DeWilde S, Harris T, Hosking FJ, Cook DG. Risk of infection in type 1 and type 2 diabetes compared with the general population: a matched cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:513–21. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding JL, Benoit SR, Gregg EW, Pavkov ME, Perreault L. Trends in rates of infections requiring hospitalization among adults with versus without diabetes in the U.S., 2000–2015. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:106–16. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hine JL, de Lusignan S, Burleigh D, Pathirannehelage S, Mc-Govern A, Gatenby P, Jones S, Jiang D, Williams J, Elliot AJ, Smith GE, Brownrigg J, Hinchliffe R, Munro N. Association between glycaemic control and common infections in people with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabet Med. 2017;34:551–7. doi: 10.1111/dme.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Gregg EW. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia. 2019;62:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casqueiro J, Casqueiro J, Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 1):S27–36. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.94253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther. 2016;5:47–56. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S73223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peleg AY, Weerarathna T, McCarthy JS, Davis TM. Common infections in diabetes: pathogenesis, management and relationship to glycaemic control. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:3–13. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo DH, Kang S, Lee YH, Ha JY, Park JS, Lee BW, Kang ES, Ahn CW, Cha BS. Current management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care clinics in Korea. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2019;34:282–90. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko SH, Han K, Lee YH, Noh J, Park CY, Kim DJ, Jung CH, Lee KU, Ko KS TaskForce Team for the Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Past and Current status of adult type 2 diabetes mellitus management in Korea: a National Health Insurance Service database analysis. Diabetes Metab J. 2018;42:93–100. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.42.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. pp. p1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker MG, Barnard LT, Kvalsvig A, Verrall A, Zhang J, Keall M, Wilson N, Wall T, Howden-Chapman P. Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. Lancet. 2012;379:1112–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijayanand P, Wilkins E, Woodhead M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a review. Clin Med (Lond) 2004;4:152–60. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-2-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel JA, Nielsen FB, Badiani AA, Assi S, Unadkat VA, Patel B, Ravindrane R, Wardle H. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health. 2020;183:110–1. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]