Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus-associated diseases are important global health concerns. As a group I carcinogen, EBV accounts for 1.5% of human malignances, including both epithelial- and lymphatic-originated tumors. Moreover, EBV plays an etiological and pathogenic role in a number of non-neoplastic diseases, and is even involved in multiple autoimmune diseases (SADs). In this review, we summarize and discuss some recent exciting discoveries in EBV research area, which including DNA methylation alterations, metabolic reprogramming, the changes of mitochondria and ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), oxidative stress and EBV lytic reactivation, variations in non-coding RNA (ncRNA), radiochemotherapy and immunotherapy. Understanding and learning from this advancement will further confirm the far-reaching and future value of therapeutic strategies in EBV-associated diseases.

Subject terms: Cancer therapy, Cancer metabolism

Introduction

Epstein–Barr virus was the first tumorigenic DNA virus that persistently infects human and some additional primate B cells. It exists as a free particle with a genome length of about 172 kb.1 EBV is transmitted primarily through saliva, resulting in asymptomatic infection in about 95% of the world’s population. In a variety of tumor types, EBV can integrate into the host genome at a remarkable rate to promote tumor development.2 As early as 1997, EBV was classified as a group I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and its associated tumors account for 1.5% of all human cancers. The etiology of EBV is primarily relevant to malignancies of epithelial and lymphatic origin, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), gastric cancer (GC), pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC), breast cancer, tonsillar cancer, hepatobiliary system cancer, malignant salivary gland tumors, and thyroid cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), including Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL), extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative carcinoma (PTLD).3–5 Recently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) identified EBV as an essential element in reducing the global cancer burden.5 Moreover, EBV plays an etiological and pathogenic role in a number of non-neoplastic diseases, including infectious mononucleosis (IM), chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH), and other systemic autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Sjogren’s syndrome (SS).6

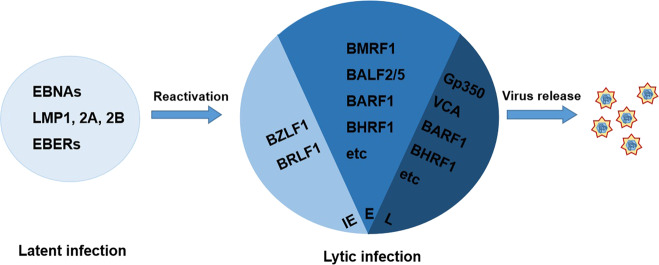

Notably, EBV infection of the host is predominantly latent. When the balance between host and virus is disturbed, EBV activation poses a risk of neoplasia. EBV has three latent infection types, type I is characterized by Burkitt’s lymphoma, which expresses only EBNA1 and the right fragment of BamHI A (BARTs) with the exception of EBERs. Type II includes NPC and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) with EBV expressing EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2, BARTs, and EBERs. Type III includes lymphoproliferative diseases in immunosuppressed patients where EBV expresses all latent infection genes.7 LMP1 as a EBV encodes important oncogenic protein with specific functions occurring during latent infection and is essential for B-cell transformation in vitro.8 It mimics CD40 auto-oligomerization to continuously activate multiple intracellular signaling pathways that mediate various malignant phenotypes.9 LMP1 plays an important role in the development and progression of EBV-positive-associated tumors that are a prognostic marker for NPC patients.10,11 LMP2A and LMP2B were first discovered in 1990.12 LMP2A is a B-cell receptor (BCR) simulator that can protect BCR-depleted B cells from apoptosis.13 Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) is necessary to maintain stability of EBV particles, EBV replication,14 and also trigger B-cell lymphoma formation in transgenic mice.15 Studies have shown that EBNA1 causes genomic instability16 and promotes tumor cell survival.17 EBNA2 and EBNA3 are critical for B-cell transformation.18 Moreover, EBV has been shown to encode non-coding RNA,19 including BamHI-A rightward transcript microRNAs (miRNAs) (BART miRNAs), BHRF1 miRNAs, and EBV-encoded RNA 1 (EBER1) and EBER2, which interact with numerous proteins and facilitate the activation of innate immunity.

EBV-associated diseases

EBV and epithelial cancers

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)

NPC is currently the most well-defined human epithelial cancer that is associated with EBV infection. In 1966, high titers of EBV-associated antibodies were found in NPCs.20 Studies have shown that an interaction of genetic, ethnic, and environmental factors may contribute to the development of NPC. In endemic areas, the EBV genome is detectable in almost all NPC tumor tissues. Subsequently, in the 1980s, serum levels of Epstein–Barr capsid antigen (VCA) immunoglobulin A (IgA) were established as one of the indicators for screening patients for NPC21 and the expression of latent genes in EBV-infected states was also discovered.22 With the use of qPCR to detect cell-free EBV DNA in 1999, a relationship between an increased risk of NPC due to EBV infection and poor prognosis was established.23 Since then, EBV DNA has become the gold standard for biological markers of NPC. Importantly, the genomic landscape of NPC has revealed that EBV latency genes provide growth and survival benefits, which result in the development of NPC. Therefore, with advances in NPC genomics, chromatin modifications enhance EBV load as a key feature of the NPC genome.24 Moreover, BALF2_CCT, as a high-risk subtype of EBV, promotes the progression of NPC in South China and facilitates early identification of high-risk individuals.25 In addition, Ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2), an epithelial growth factor-associated receptor, benefits EBV entry into epithelial cells.26 Importantly, common fragile regions are favored loci for EBV integration, which are genomic hotspots for DNA damage and vulnerable to genomic rearrangements. More recently, a study reports that EBV integration occur at 9.6% in NPC. These discoveries provide novel, potential intervention strategies for preventing EBV infection.

EBV-associated gastric cancer (EBVaGC)

Since 1992, the first demonstration of EBV in typical gastric adenocarcinomas occurred and facilitated the understanding of EBV in GC development.27 Approximately 9% of gastric cancer (GC) patients are EBV-positive, and these cases have a distinct molecular phenotype and clinical characteristics.28 Global epigenetic methylation and counteraction of the antitumor microenvironment are two major characteristics of this subtype of GC. With advances in the diagnosis and treatment of EBV infection, in situ hybridization (ISH) of EBER in biopsy specimens facilitate the diagnosis of EBVaGC.29 Recently, EBV can integrate into host genomes at 25.6% in GC tumorigenesis.2 In addition, immune checkpoint therapy for advanced stage or metastatic EBVaGC may be effective in treating this disease.30

Breast cancer

The first association of EBV infection with breast cancer was reported in 1995.31 Recently, several studies showed that EBV infection leads to more malignant transformation of breast epithelial cells and affects patient prognosis.32,33 EBV leads to a 4.74-fold increase in risk of breast cancer development compared with a control group.32 The potential oncogenesis mechanism of EBV is related to viral proteins, such as LMP1 that activate the Her2/Her3 signaling cascades.33

Several rare non-typical EBV-associated tumors, including pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC),34 tonsillar cancer,35 hepatobiliary system cancer,36 malignant salivary gland tumors,37 and thyroid cancer38 have also been reported. Among these, LELC is a rare and distinct subtype of primary lung cancer characterized by EBV infection and high LMP1 expression.34 These findings further expand our insight into the involvement of EBV in tumorigenesis.

EBV and lymphatic system cancers

HL and NHL

EBV-associated lymphomas consist of HL and NHL, of which the most widely studied NHL are Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.39 EBV particles were first detected in BL back in 1964.40 The EBV genome was next revealed in BL41 and the relationship between EBV and lymphoma was successfully determined epidemiologically in the 1970s.42 Moreover, the identification of EBV DNA in HL serum43 suggests that EBV may serve as a biomarker for early disease detection and monitoring patient treatment. In the 1980s, the EBNA protein was detected in HRS cells of a HL patient44 and then EBV genome was sequenced in HL and NK/T-cell lymphoma.45 Also, ENK/T-cell lymphoma was characterized by EBV infection of T or NK cells, which express a latency II pattern with variable LMP1 expression.

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative carcinoma (PTLD)

PTLD is a serious complication that occurs after solid organ, bone marrow, or blood stem cell transplantation, and is associated with EB virus infection in 60–80% of patients.46 In post-transplant patients, immunosuppression leads to repression of T-cells with a subsequent uncontrolled proliferation of lymphoid cells.47 With the discovery of the EBV genome and antibodies in 1980,48 a majority of PTLD patients have been tested for the presence of LMP1 and EBNA2/EBNA3 expression. The first successful use of EBV-specific T-cell therapy in EBV-associated lymphocyte proliferation occurred in 1995.49 Therefore, monitoring of EBV infection in post-transplant patients is of paramount importance.

EBV chronic infectious diseases

Infectious mononucleosis (IM)

IM is a self-limiting disease caused by primary EBV infection, which was defined in 1968.50 Symptoms of IM are caused by an excessive immune response to EBV infection that presents with a “triad” of fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy, with a marked increase in peripheral blood lymphocytes and the appearance of heterogeneous lymphocytes.51

Chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV)

CAEBV is a serious EBV infection with clinical manifestations of persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms.52 The main features of the advancement of the disease include dramatically enhanced levels of EBV DNA in the blood and infiltration of organs by positive EBER1-positive cells. Patients often exhibit fever, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatitis, or pancytopenia.53,54 EBV infection of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells performs a pivotal contribution to the pathogenesis of CAEBV. Usually, T-cell infections have severe clinical symptoms and a poor prognosis. However, NK-cell-type infection patients favor for transformation into aggressive NK-cell leukemia or extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.55 Besides, in adult CAEBV, HLH may be the other clinical endpoint.56–58

EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH)

EBV-HLH is a severe, life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome of EBV infection, clinically characterized by abnormal proliferation and activation of lymphocytes and macrophages, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, blood cytopenias, hepatitis and/or hepatomegaly.59 Importantly, the timing and severity of these appearances can assist in distinguishing between EBV infection alone and HLH-complicated EBV infection.60

EBV-related autoimmune diseases

EBV has been shown to be the cause of several autoimmune diseases, and studies have shown that EBV-infected individuals have a higher frequency of disease, including SLE, RA, SS, compared to non-infected individuals.6 As EBV plays an etiological role in autoimmune diseases, serological measures of EBV reactivation provide additional biomarkers to identify high-risk individuals. The common features of these EBV-related autoimmune diseases are elevated plasma viral loads and levels of EBV-directed antibodies that result in decreased EBV-directed cell-mediated immunity, suggesting the presence of widespread lytic EBV infection in patients.61 Furthermore, EBV reactive and the host’s immune response result in different diseases patterns and clinical manifestations.

DNA methylation alterations and clinical applications in Ebv-associated malignancies

Regulation of DNA methylation by EBV

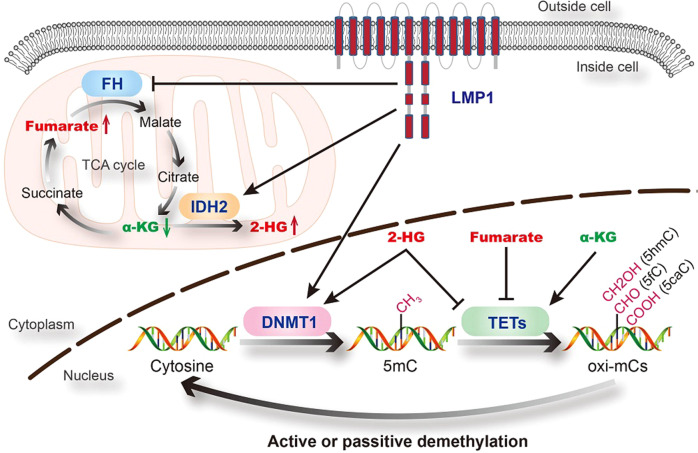

DNA methylation in mammalian organisms is a reversible process, which mostly occurs by the addition of a methyl group to the C-5 position of cytosine in the CpG sequence context. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) transfer methyl groups from S-adenosyl-L-methionone (SAM) to cytosine and create 5-methylcytosine (5mC). DNMT1 is the most abundant DNMT in mammalian cells and it maintains methylation status during cell replication.62 Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenases (TETs) oxidize 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), which in turn undergo further oxidation into 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), thereby mediating DNA demethylation.63 The balance of DNA methylation- demethylation dynamics is maintained by DNMTs and TETs.

EBV infection is an epigenetic driver, which results in aberrant DNA methylation.64,65 First, EBV activates DNA methylation pathways. Tsai et al.66 reported that EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (EBV-LMP1) enhances DNMT1 transcription and expression by activating the JNKs signaling pathway. We previously showed that EBV-LMP1 not only upregulates DNMT1 expression and activity, but also promotes its mitochondrial translocation.67 Secondly, EBV inhibits DNA demethylation pathway. TET family proteins, especially TET2, are downregulated during EBV infection, and TET2 may function as a resistance factor against EBV-induced DNA methylation acquisition.68 TET enzymes require α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) as an essential co-substrate to catalyze the conversion of 5-mC to 5-hmC. With a similar structure to α-KG, fumarate, succinate, and 2-HG could competitively inhibit the enzymatic activity of TETs.69 Recently, we revealed that EBV-LMP1 promotes the accumulation of fumarate and 2-HG, and the reduction of α-KG, which consequently leads to the inactivation of TETs.70,71 Moreover, 2-HG could also regulate DNMT1 activity by enhancing its binding to selected DNA regions.72 EBV infection might tip the balance in DNA methylation-demethylation dynamics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of DNA methylation by EBV (LMP1). The balance of DNA methylation- demethylation dynamics is maintained by DNMTs and TETs. DNMTs transfer methyl groups to cytosine and create 5mC. TETs iteratively oxidize 5mC to generate oxi-mCs (5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC). EBV (LMP1) enhances DNMT1 expression and activity, and also inhibit the enzymatic activity of TETs, which might tip the balance. FH fumarate hydratase, IDH2 isocitrate dehydrogenase 2

CpG island promoter methylation of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) is one of the most characteristic abnormalities in EBV-associated malignancies. The CpG island methylation phenotype (CIMP) is defined as the high activity of global and nonrandom CpG island methylation. EBV infection mediates onco-epigenetic effects and is closely associated with CIMP.73 The most representative feature of EBV-positive GCs is an extensive hypermethylation phenotype, EBV-CIMP, which includes CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation.74 CIMP plays a driving role in EBV-associated malignancies, which leads to promoter hypermethylation and silencing of a series of functional genes (Tables 1–3).

Table 2.

Hypermethylated genes in EBV-associated GC

| Gene names | Full name | Gene function | Methylation status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQP3 | Aquaporin 3 | Water channel | 95.8% (23/24) | 449 |

| B4GALNT2 | Beta-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase 2 | Blood group systems biosynthesis | 50.8% (32/63) | 450 |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, P16 | Cell cycle control | 86.7% (13/15) | 451 |

| 68.2% (15/22) | 452 | |||

| CDKN2B | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B, P15 | Cell cycle control | 86.7% (13/15) | 451 |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin | Cell–cell adhesion | 100% (15/15) | 451 |

| CYLD | CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase | Deubiquitination | 56.0% (14/25) | 453 |

| DAPK1 | Death-associated protein kinase 1 | Apoptosis | 73.3% (11/15) | 451 |

| IRF5 | Interferon regulatory factor 5 | Transcription factor | 76.5% (13/17) | 454 |

| MARK1 | Microtubule affinity regulating kinase 1 | Cell migration | 68.0% (17/25) | 455 |

| MINT2 | amyloid beta precursor protein binding family A member 2 | Signal transduction | 92.0% (23/25) | 452 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | PI3K/AKT signaling | 64.3% (18/28) | 456 |

| REC8 | REC8 meiotic recombination protein | Meiosis | 92.3% (12/13) | 457 |

| RUNX3 | RUNX family transcription factor 3 | Transcription factor | 96.0% (24/25) | 452 |

| S100A4 | S100 calcium binding protein A4 | Signal transduction | 50.0% (12/24) | 455 |

| SCRN1 | Secernin 1 | Exocytosis | 48% (12/25) | 455 |

| SOX9 | SRY-box transcription factor 9 | Transcription factor | 85.7% (6/7) | 458 |

| SSTR1 | Somatostatin receptor 1 | G-protein-coupled receptor signaling | 75% (9/12) | 459 |

| ST3GAL6 | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha- 2,3- sialyltransferase 6 | Glycosphingolipids biosynthesis | 44.4% (28/63) | 450 |

| TP73 | Tumor protein p73 | Stress response | 96.0% (24/25) | 455 |

| 100% (15/15) | 451 | |||

| 96.0% (24/25) | 452 | |||

| WNT5A | Wnt family member 5A | WNT signaling | 91.3% (21/23) | 460 |

Table 1.

Hypermethylated genes in EBV-associated NPC

| Gene names | Full name | Gene function | Methylation status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | Regulator of WNT signaling pathway | WNT signaling | 34.0% (17/34) | 439 |

| CADM1 | Cell adhesion molecule 1 | Cell–cell adhesion | 69.8% (37/53) | 83 |

| 67.9% (19/28) | 440 | |||

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, P16 | Cell cycle control | 66.0% (35/53) | 83 |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin | Cell–cell adhesion | 73.7% (18/28) | 441 |

| CDH13 | Cadherin 13 | Cell–cell adhesion | 77.4% (41/53) | 83 |

| CHFR | Checkpoint with forkhead and ring finger domains | Cell cycle control | 58.5% (31/53) | 83 |

| DAPK1 | Death-associated protein kinase 1 | Apoptosis | 27.3% (60/220) | 84 |

| DAB2 | DAB adaptor protein 2 | Proliferation | 65.2% (30/46) | 442 |

| DCC | DCC netrin 1 receptor | Signal transduction | 50.0% (23/46) | 439 |

| DLEC | DLEC1 cilia and flagella-associated protein | Proliferation | 60.4% (29/48) | 439 |

| DLC1 | DLC1 Rho GTPase activating protein | G-protein signaling | 76.9% (40/52) | 83 |

| 43.8% (21/48) | 439 | |||

| INPP4B | Inositol polyphosphate -4-phosphatase type II B | Phosphatidylinositol signaling | 60.0% (9/15) | 443 |

| ITGA9 | Integrin subunit alpha 9 | Cell–cell adhesion | 55.6% (20/36) | 444 |

| KIF1A | kinesin family member 1A | Membrane trafficking | 56.0% (28/50) | 439 |

| MAOA | Monoamine oxidase A | Amino acid metabolism | 40.7% (22/54) | 445 |

| miR-31 | microRNA 31 | Post-transcriptional regulation | 87.5% (14/16) | 446 |

| PRDM2 | PR/SET domain 2, RIZ1 | Histone methyltransferase | 56.6% (30/53) | 83 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | PI3K/AKT signaling | 80.0% (40/50) | 447 |

| RARB | Retinoic acid receptor beta | Nuclear receptor | 15.9% (35/220) | 84 |

| RASSF1A | Ras association domain family member 1 | Cell cycle control | 24.1% (53/220) | 84 |

| 75.5% (40/53) | 83 | |||

| 82.1% (23/28) | 440 | |||

| RASSF2A | Ras association domain family member 2 | Cell cycle control | 29.2% (14/48) | 83 |

| RRAD | Ras related glycolysis inhibitor and calcium channel regulator | Calcium channel | 74.3% (26/35) | 448 |

| UCHL1 | ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 | Protein ubiquitination | 64.0% (32/50) | 439 |

| WIF1 | WNT inhibitory factor 1 | WNT signaling | 51.8% (114/220) | 84 |

| 61.2% (30/49) | 83 | |||

| WNT7A | Wnt family member 7A | WNT signaling | 69.4% (25/36) | 444 |

Table 3.

Hypermethylated genes in other EBV-associated tumors

| Gene names | Full name | Gene function | Cancer type | Methylation status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2L11 | BCL2 like 11 | Apoptosis | BL | 92.9% (13/14) | 461 |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, P16 | Cell cycle control | CSCC | 61.0% (25/41) | 462 |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin | Cell–cell adhesion | OSCC | 82.4% (56/68) | 463 |

| HACE1 | HECT domain and ankyrin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | Protein ubiquitination | NKTCL | 100% (6/6) | 464 |

| MGMT | O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase | DNA repair | OSCC | 55.9% (38/68) | 463 |

| PRDM1 | PR/SET domain 1 | Transcriptional regulation | BL | 50.0% (11/22) | 465 |

BL Burkitt’s lymphoma, CSCC cervical squamous cell carcinoma, OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, NKTCL natural killer/T-cell lymphoma

Interestingly, DNA hypomethylation induced by EBV has also been observed in a few studies. For example, the S100 calcium binding protein A4 (S100A4) is overexpressed in LMP2A-positive NPC tissues and DNA hypomethylation plays a critical role in S100A4 regulation.75 In Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a set of tumor-related genes known to be silenced by promoter hypermethylation (e.g., RASSF1, DAPK, MGMT) are more frequently hypermethylated in EBV-negative compared to EBV-positive cases.76 EBV might also take part in the redistribution of DNA methylation modification sites.

The clinical significance of DNA methylation as a biomarker in EBV-associated malignancies

Abnormal DNA methylation has been investigated in NPC biopsies, nasopharyngeal brushings, and blood samples. Thus, aberrant DNA-methylated genes might be used as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers.

In the EBV genome, DNA methylation takes an important part in lytic cycle regulation. The EBV genome is gradually methylated during the establishment of latency, while it becomes unmethylated in the viral lytic cycle. EBV DNA methylation could be used as a biomarker. For example, Zheng et al.77 found that a combination of the degree of EBV DNA methylation and EBV DNA load showed great potential for diagnosing NPC in nasopharyngeal brushing samples (sensitivity = 0.98, specificity = 0.95). The viral genome-wide methylation profiling of circulating EBV DNA in plasma demonstrated differential methylation patterns between NPC and non-NPC subjects. When combining the plasma EBV DNA load and methylation test pattern in plasma samples, the sensitivity was 0.97 and the specificity was 0.99 for population screening of NPC.78

Tumor-related genes are associated with EBV infection and carcinogenesis and some of these are summarized in Table 1. For instance, RASSF1A promoter methylation is a promising noninvasive biomarker for the diagnosis of NPC as determined from tissue and brushing samples (tissue: sensitivity = 0.72, specificity = 0.99, AUC = 0.98; brushing: sensitivity = 0.56, specificity = 1.00, AUC = 0.94).79 High levels of TIPE3 promoter methylation is associated with worse overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), which could be an independent prognostic factor in NPC.80 The methylation level of the HOPX promoter is a potential prognostic biomarker for NPC and high levels are associated with poor prognosis.81 Patients with RAB37 hypermethylation are more sensitive to docetaxel-containing induction chemotherapy and RAB37 methylation levels might be used to predict chemotherapy sensitivity.82

Recently, panels of methylation genes, which are more sensitive than single biomarkers, have been reported. Hutajulu et al.83 found that combined analyses of five methylation markers (i.e., RASSF1A, p16, WIF1, CHFR, RIZ1) provided good discrimination between NPC and non-NPC patients with a detection rate of 98%. A panel of four methylated genes (i.e., RASSF1A, WIF1, DAPK1, RARβ2) in combination with the EBV DNA test increase the sensitivity for NPC detection at an early stage (sensitivity = 0.96, specificity = 0.65, AUC = 0.83).84 The genome-wide DNA methylation profiling study revealed a methylation gene panel (i.e., WIF1, UCHL1, RASSF1A, CCNA1, TP73, SFRP1) as a prognostic biomarker for OS and DFS, which was also associated with the efficacy of concurrent chemotherapy in NPC.85

Targeting DNA methylation for therapy against EBV-associated malignancies

DNA hypermethylation correlates with poor survival outcomes in patients with cancer, especially with EBV-associated tumors. DNMT1 (maintaining DNA hypermethylation of specific genes) is currently the most important target for epigenetic cancer therapy. DNMT inhibitors, such as Vidaza® (5-azacytidine, Celgene) and Dacogen® (decitabine or 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine, SuperGen) have been approved by the FDA for cancer therapy.86 A few studies have focused on EBV-associated malignancies. In NPC preclinical studies, 5-azacytidine has shown the potential to improve outcomes with radiotherapy.87 However, in a phase II study, CC-486 (oral azacitidine) did not show sufficient clinical activity to support further development as a monotherapy in advanced NPC.88

Some natural compounds also showed efficacy as DNMT1 inhibitors. Previous studies from our group and other labs have reported that a farnesyl phenolic compound, grifolin, isolated from the fresh fruiting bodies of the mushroom Albatrellus confluens, exhibits extensive bioactivity.67,89–95 Most recently, we demonstrated that grifolin treatment inhibits DNMT1 expression and activity, as well as its mitochondrial translocation. Consequently, it results in demethylation of the pten gene and inhibition of downstream AKT signaling, which effectively attenuates glycolytic flux in NPC cells. Moreover, demethylation of the mtDNA D-loop region and upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes are observed with grifolin treatment in NPC cells.67

Metabolic reprogramming and clinical application to Ebv-associated cancers

Glycolysis in NPC

Enhanced glucose metabolism is a common hallmark of cancer. Virus can increase aerobic glycolysis and use glucose biosynthetically.

EBV infection alters glucose metabolism and cause the Warburg Effect. For example, EBV upregulation of all glycolytic enzymes including rate-limiting enzyme hexokinase 2 (HK2), also EBV infection induced substantial relocalization of glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) and enhanced glycolytic flux. Elevated glycolysis has been demonstrated by EBV oncoprotein LMP1.96 An earlier study showed that GLUT-1 is highly expressed in the nasopharyngeal tissues of patients with NPC, and its expression is associated with clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, and EB virus infection.97 Some researchers suggested that Epstein–Barr virus-encoded LMP1 changes the metabolic profile and promotes increased glycolysis in NPC cells.98,99 According to Xiao et al.,98 a large-scale metabolic profiling approach showed that EBV (LMP1) regulated metabolic changes in NPC cells and, in particular, the promotion of glycolysis. HK2 was identified as a key modulator of LMP1-induced glycolysis, and conferred proliferative advantages and poor prognosis of NPC patients following radiation therapy. The LMP1-perturbed PI3-K/Akt-GSK3β-FBW7 signaling axis resulted in the stabilization of c-Myc, which was confirmed to be crucial for LMP1-induced glycolysis and confers NPC cells resistance to apoptosis.98 Lu et al.99 revealed a novel mechanism for LMP1-mediated radio-resistance by suppressing the DNA damage response (DDR) through DNA-PK/AMPK signaling. LMP1 reduced the phosphorylation of AMPK and disturbed its subcellular localization after irradiation. The findings showed that inhibition of AMPK signaling also accelerated glucose uptake and lactate production and conferred resistance of NPC cells to apoptosis induced by irradiation. Reactivation of AMPK by metformin, a pharmacological activator of AMPK, could substantially reverse radio-resistance of LMP1-positive NPC cells both in vitro and in vivo.99 EBV epigenetically reprogram several Hox genes expression in NPC cell lines and tumor biopsies. Ectopic expression of HoxC8 inhibits NPC cell growth in vitro and in vivo, modulates glycolysis and regulates the expression of TCA cycle-related genes.100 Recently, Luo et al.67 analyzed the metabolites of 13C6-d-glucose-traced NPC cells by using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), and found that glycolytic flux in LMP1-overexpressing cells was markedly increased by about 90% compared to that in LMP1-negative cells. In addition, 13C-labeled pyruvate and lactate levels were markedly elevated, whereas 13C-labeled metabolite levels of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, including 13C-citrate, 13C-α-ketoglutarate, 13C-fumarate, and 13C-malate were significantly decreased.67 Importantly, our latest findings revealed that LMP1-positive NPC cells have a powerful mitochondrial fission function to sustain metabolic changes. Moreover, the phosphorylation of mitochondrial dynamin- protein Drp1 (Ser616 or Ser637) was indispensable for the increased glycolytic metabolism regulated by LMP1. The enhancement of glycolysis might be a crucial adaptive function of cancer cells under the high fission state of mitochondria induced by EBV infection stress.101 Increasing evidence suggests the progression of tumors might not only rely on the cancer cells themselves but also be influenced by the surrounding stroma cells. Extracellular vesicles packaged LMP1 activated normal fibroblasts (NFs) to cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) via the NF-κB p65 signaling pathway, which promote tumor progression via autophagy and stroma-tumor metabolism coupling.102

Fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGFR1) signaling is a key pathway in LMP1-mediated growth transformation. LMP1-mediated FGFR1 activation contributes to aerobic glycolysis and transformation of epithelial cells, thereby implicating FGF2/FGFR1 signaling activation in the EBV-driven pathogenesis of NPC.103 EBV-LMP1 induces glycolytic addiction to enhanced cell motility in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. EBV-LMP1 activates IGF1-mTORC2 signaling and nuclear acetylation of the Snail promoter by PDHE1α, an enzyme involved in glucose metabolism, to enhance cell motility, thereby driving cancer metastasis. The IGF1/mTORC2/PDHE1α/Snail axis correlates significantly with disease progression and poor prognosis in NPC patients.104

EBV infection and enhanced glucose metabolism might drive the development and progression of EBV-associated cancers. These findings provide a new perspective to reveal for the interplay between EBV infection and host metabolism-associated molecules in driving cancer pathogenesis. Understanding these key events might reveal novel therapeutic targets and potentially reverse resistance to treatment therapies in EBV-associated cancers patients.

Targeting glycolysis by natural compounds

Natural compounds derived from plants, fungi, and marine organisms are widely used as anticancer drugs in preclinical/clinical development or in clinic.105 A number of natural compounds that target metabolism-related pathways show inhibition activity on cancer cells.106 Neoalbaconol (NA), isolated from the fruiting body of the mushroom Albatrellus confluens, is a novel small-molecular compound with a drimane-type sesquiterpenoid structure.107 In response to various stimulations, PDK1 can activate phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) and then Akt, playing pivotal roles in energy metabolism, cell proliferation and migration. By using EBV-positive C666-1 cell line, we found that neoalbaconol inhibits phosphorylation of Akt and downstream targets, including TSC2, mTOR, and p70S6K1.108 Also, neoalbaconol inhibited the activity of key energy metabolic enzyme hexokinase 2 (HK2), which eventually resulted in a striking energy crisis. Furthermore, neoalbaconol treatment not only significantly decreased the glucose concentration in the media but also blocked ATP generation.108 Seahorse XFp cell energy phenotype test showed that cell oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were decreased after neoalbaconol treatment. In addition, by using a nude mouse model, we found that neoalbaconol decreases C666-1 cell xenograft tumor growth and suppresses the PI3K/Akt pathway in vivo.108 In conclusion, neoalbaconol regulates PDK1/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K1 signaling pathway and glycolytic gene hexokinase, thus decreasing cell glycolysis and ATP synthesis to induce NPC cell death and inhibit tumor growth in vivo. This study is expected to contribute to the rational design and critical assessment of novel anticancer therapies based on natural compounds-mediated glycolysis reprogramming in EBV-related cancer.

Lipid alteration and fatty acid oxidation in EBV-associated cancers

Aberrant Lipid reprogramming is involved in promoting tumor progression and membrane homeostasis. EBVaGC has a different phospholipid and triacylglycerol (TG) expression pattern than EBV-negative gastric cancer. Fifteen of these lipid-related pathways were associated with EBVaGC metabolites. Analysis of the three major lipids, phospholipids, sphingolipids and neutral lipids revealed that TG and ceramide were downregulated, whereas phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) were upregulated in EBVaGC. These findings may help explain the mechanism of EBVaGC tumorigenesis.109 Furthermore, we know that in primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma, EBV-LMP1 induces lipid synthesis and lipid droplet formation. Lo et al.110 reported a novel function of LMP1 in promoting nascent lipogenesis. EBV-LMP1 increased the expression, maturation, and activation of steroid regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and its downstream target fatty acid synthase (FASN). In addition, elevated FASN expression was associated with poor survival in patients with invasive disease and NPC. Their findings suggest that LMP1 activation of SREBP1-mediated adipogenesis promotes tumor cell growth and is involved in the EBV-driven pathogenesis of NPC, which propose a new therapeutic protocol for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma using lipogenesis inhibitors.

Fatty acids are fundamental cellular components and energy sources. Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) is increasingly recognized as a crucial metabolic characteristic of cancer. For example, a group of the OXPHOS cluster diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (OXPHOS-DLBCL), which is significantly enriched in genes involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, predicts potential differences in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism compared with other DLBCL groups. Notably, palmitate is a predominant respiratory fuel in OXPHOS-DLBCLs. NADPH and ATP is mainly supplied through the fatty acid β-oxidation and coupled oxidative phosphorylation, providing growth and proliferation advantages.111

Moreover, lipid reprogramming may play a vital role in mediating radiation resistance in NPC (Fig. 2). An active FAO is a vital signature of NPC radiation resistance, and the rate-limiting enzyme of FAO, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 A (CPT1A), was consistently upregulated in these cells.112 The PGC1α-CEBPB interaction promotes CPT1A transcription, which can facilitate FAO, and maximizes ATP and NADPH production, contributing to radiation resistance.113 Furthermore, the IHC scores in a tissue microarray indicated that PGC1α was highly expressed in non-keratinizing undifferentiated NPC, which corresponds to worse overall survival after radiation therapy in NPC.113 More interestingly, the CPT1A-Rab14 interaction plays roles in CPT1A-mediated radiation resistance by facilitating fatty acid trafficking. Inhibition of CPT1A resensitized NPC cells to radiation therapy by activating mitochondrial apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo.112 Targeting the PGC1α/CEBPB/CPT1A/FAO signaling axis by etomoxir (ETO) or genetic knockdown could be a potential strategy to improve the therapeutic effects of radiotherapy in NPC.113 Mechanistic studies of abnormal tumor fatty acid metabolism and radiotherapy resistance will help enrich our understanding of tumor lipid metabolism reprogramming and provide new perspectives and novel molecular targets for tumor radiotherapy resistance. However, how the EBV plays a role in this FAO need further exploration.

Fig. 2.

A schematic to illustrate CPT1A-mediated radiation resistance in NPC. PGC1α-CEBPB interaction promote the transcription, expression and enzyme activity of CPT1A, and CPT1A-Rab14 interaction promote fatty acid trafficking between lipid droplets and mitochondria, which facilitates fatty acid utilization and maximizes ATP and NADPH production, leading to resistance to radiation

Glutamine metabolism in NPC

Glutamine is one of the important precursors contributing to de novo nucleotide synthesis, which provides the nitrogen that is required for purine and pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis. Glutamine synthetase (GS) is responsible for glutamine metabolism in cancer therapeutic responses, in particular under irradiation-induced stress. GS is transcriptionally regulated by STAT5 and highly expressed in radiation-resistant NPC cells. High expression of GS drives metabolic flux toward nucleotide synthesis to enable efficient DNA repair, then acquired radiation resistance and survival advantages. Targeting GS and the associated pathways may provide therapeutic benefits to patients with both intrinsic and acquired radiation resistance.114

One-carbon metabolism in EBV-induced B-cell transformation

One-carbon (1C) has a critical contribution to speedy cell growth in support of embryonic progression, cancer and T-cell activation. Mitochondrial 1C metabolism stands out as one of the highest induced pathways for EBV infection. EBV triggers mitochondrial 1C metabolism in newly infected B cells, and 1C upregulation is necessary for efficient growth, survival, and transformation of these cells. Besides, EBV induced mitochondrial folate metabolism enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2), which was driven transcriptionally by EBV-encoded protein EBNA2 and MYC synergistically. EBV-induced mitochondrial 1C metabolism drives nucleotide, mitochondrial NADPH, and glutathione production. Which provide an attractive rationed for developing novel mitochondrial 1C metabolic inhibitors for the treatment of B lymphomas.115,116

Clinical application of metabolic analysis in EBV-related cancers

Serum metabolic profiling and radiotherapy in NPC

Based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) metabolomics coupled with partial least squares-discriminant analysis, an NPC discrimination model was established with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 92%. Seven metabolites, including glucose, linoleic acid, stearic acid, arachidonic acid, proline, β-hydroxybutyrate, and glycerol 1-hexadecanoate, were identified as contributing most to the discrimination of NPC serum from healthy controls. Metabolic footprints of 20 NPC patients treated with standard radiotherapy are visually submitted to validate the model applied for therapeutic evaluation. The coincident rate of the trends of metabolic footprints to the actual clinical prognosis trend was ~80%. The metabolic profiling approach as a novel strategy may be capable of delineating the potential of metabolite alterations in discrimination and therapeutic evaluation of NPC patients.117

18F-FDG-based imaging in EBV-associated tumors

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), which identifies viable tumors by detecting enhanced tumor glycolysis, has long been used as an imaging modality for staging NPC and detecting recurrence of the disease. HK2 has been recognized as a therapeutic target. Two NPC clinical investigations showed that high 18F-FDG uptake indicates poor outcome in patients with NPC118,119, which is highly dependent on HK2. Xiao et al.98 suggested that therapeutic strategies targeting multifunctional metabolic genes, such as HK2, would provide more effective treatment options for NPC.

Previously, associations of combined 18F-FDG-PET and MRI parameters with histopathological features depended on tumor grading and correlated strongly with tumor cell expression of Ki-67 and HIF-1α in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).120 Also, this metabolic imaging biomarker-based parameters are useful for evaluation of prognostic significance. Maximum and mean standardized uptake values (SUVmax, SUVmean) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) of the primary tumor could predict a poor outcome in NPC patients.121

Recently, the plasma EBV DNA titer has been recognized as a particularly promising prognostic biomarker. For instance, investigations have compared the prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET parameters and the EBV DNA titer during radiotherapy in patients with primary M0 NPC. Combining 18F-FDG-PET- derived parameters and EBV DNA to subtype patients with primary NPC is more beneficent than the conventional TNM system. Furthermore, 18F-FDG PET-derived parameters and the EBV DNA titer can predict outcome in patients with primary NPC, which may represent an imaging-guided and biomarker-guided double evaluation strategy in the future.122

Thus, all the evidences point out that EBV infection effectively disrupts cellular metabolic homeostasis, and understanding these mechanism-based metabolic reprogramming-induced EBV will reveal new avenues for future diagnosis and treatment.

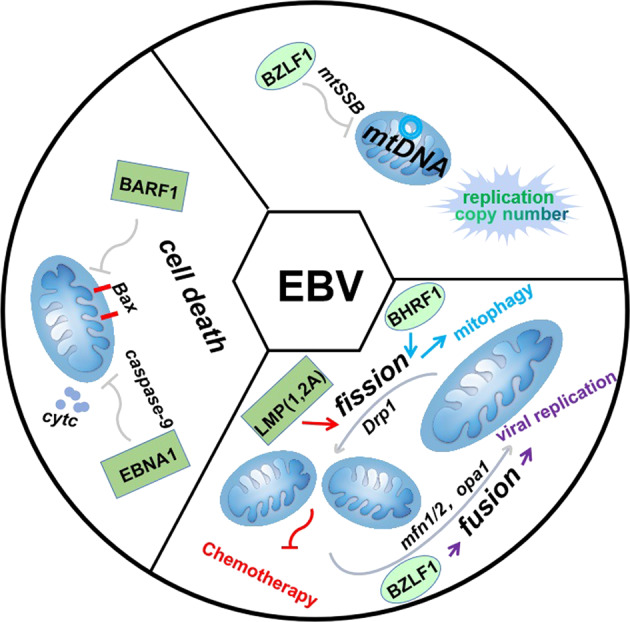

Mitochondria and Ebv-associated tumors

Mitochondria play an important role in cellular energy dynamics, and are the hubs that connect numerous signaling pathways in tumors. Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics, mitochondrial-related cell death are involved in coordinated processes of cellular physiological and pathological regulation, highlighting the multidimensional function of mitochondria in cancers (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mitochondria play an important etiological and pathogenesis role in the EBV-associated cancers. EBV has a new function in remodeling of mitochondrial dynamics during latency and lytic infection. EBV-encoded latent oncogene BARF1 and EBNA1 suppress the apoptotic pathways by decreasing Bax translocation to mitochondria and activating casepase-9. The BZLF1 protein encoded during EBV lytic activation inhibits the replication and copy number of mtDNA

Mitochondria DNA (mtDNA)

Mitochondria DNA (mtDNA) and NPC

Mitochondrial biosynthesis and function are, of course, largely controlled by mitochondrial DNA. Ethidium bromide can consume mitochondrial DNA and inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells, indicating that mitochondria are important contributors to tumor growth and invasion.123 One early study demonstrated that mutations in mitochondrial DNA may be involved in the development and progression of NPC. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA are mainly caused by the deletion of its common deletion (CD) of 4981 bp, the accumulation of which in patients might be involved in the development and progression of NPC linked with patient age and clinical stage.124 The mitochondrial genome is also considered to be one of the genetically susceptible areas in NPC. Research has indicated that NPC patients often exhibit higher mtDNA mutation frequency compared to normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues. Patients with NPC showed a high frequency of mutation at mtDNA np16362, np16519, and mtMSI D310 and have family heritability.125 The effect of mtDNA haplogroup on NPC occurrence was evaluated in 201 NPC patients with matched controls. Results indicated that patients with haplogroup R9, and its sub-haplogroup F1, in particular, exhibited the most vigorous development of NPC.126

Mitochondria DNA (mtDNA) and EBV

Mitochondria have been known to serve as targets for tumor virus aggression and also to intervene in viral tumorigenesis. BZLF1 is a DNA binding protein belonging to the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family.127 MtDNA replication is initiated by transcription-mediated priming facilitated by the mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein (mtSSB). MtSSB is a tetramer composed of four 16 kDa subunits and binds to mitochondrial DNA at the transcription and replication initiation area.128 BZLF1 targets mtSSB and mediates the translocation of mtSSB from mitochondria into the nuclear compartment, thus inhibiting mtDNA replication, and decreasing mtDNA copy number.129

Mitochondrial dynamics triggered by EBV

Mitochondrial dynamics mainly consist of two mutually restrictive shaping processes: mitochondrial fission and fusion.130 Under severe stress, mitochondria tend to divide and exhibit rounded, fragmented morphology. When subjected to mild stimuli, mitochondria predominantly show a rod-shaped fused morphology.131 At present, mitochondrial dynamics have been used to classify tumors, predict clinical prognosis, and therapeutic response. The key regulators involved in mitochondrial remodeling proteins include mitochondrial dynamin-related protein (Drp1), mitochondrial outer membrane receptor proteins (Fis1, Mff, mid49/51) and mitochondrial fusion proteins (Mfn1/2, OPA1). These shaping proteins contribute more to mitochondrial function and cell metabolism.132 Drp1 is a factor in mitochondrial dynamics that is involved in tumor migration and pathogenesis.133–135 Crucially, phosphorylation of Drp1 has a vital role in the modulation of Drp1 activity. Increasing evidence indicates that Ser616 phosphorylation facilitates the movement of Drp1 from the cytoplasm to the outer mitochondrial membrane. However, Ser637 phosphorylation causes a reversal of this procedure.136

Mitochondrial dynamics and EBV latency infection

Mitochondrial heterogeneity may be responsible for the recurrence and treatment resistance of EBV-associated tumors.67,124 EBV encodes the oncogene LMP1 and latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A), which play important roles in gene expression and are thought to be involved in EBV-mediated tumorigenesis.137 EBV expresses oncogenic proteins that can interfere with the function of CDKs and induce a number of signals that put their genomes replicate into the host’s cells.138 Recently, we revealed that CDK1 binds to Drp1 in the mitochondria to form a complex that enhances mitochondrial fission. Also, EBV-LMP1 has a novel function in mitochondrial remodeling as evidenced by enhanced mitochondrial fission and glycolytic metabolism through regulation of the cyclin B1/Cdk1/Drp1 signaling axes. This study implies that changes in mitochondrial morphology caused by EBV- encoded oncogenes promote mitochondrial function and reprogramming metabolism.101 Another latent protein, LMP2A, has also been reported to promote mitochondrial fission, induce cell migration, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in gastric and breast cancer cells, suggesting that EBV-driven mitochondrial fission promotes tumor cell survival and mediates drug-resistant therapy.139

Mitochondrial dynamics and EBV lytic infection

Zta (BZLF1 or EB1) and Rta (BRLF1) are immediate early response proteins, which are expressed at the early stage of EBV infection and have been reported to reorganize mitochondrial morphology during EBV lytic replication. Interestingly, a fusion event initiated by BZLF1 expression and the expression of BRLF1 resulted in the relocalization of mitochondria to one side of the nucleus.140 Furthermore, BHRF1 is expressed during the viral productive cycle and is able to translocate to mitochondria and shows strong functional homology with the human Bcl2 protein. BHRF1 prevents type I IFN pathway activation by encouraging mitochondrial fragmentation, which ultimately contributes to autophagosomes degradation by mitophagy.141 Thus, the loss of control of the EB virus stress over mitochondrial structure will be another checkpoint to overcome.

Targeting mitochondrial signaling

Targeting mitochondrial fission or fusion

Proteins involved in mitochondrial fusion and fission may participate in cancer cell resistance to apoptotic stimuli and serve as new therapeutic targets. Based on the observed high fission-to-fusion ratio in apoptotic cells, fission is believed to be a necessary prerequisite for apoptosis.142 The TP53-regulated inhibitor of apoptosis (TRIAP1) was discovered to be aberrantly overexpressed and associated with poor survival in NPC patients. Furthermore, miR-320b is a negative regulator of TRIAP1 and upregulation of miR-320b suppresses NPC cell proliferation and encourages mitochondrial fission and apoptosis.143 1,8-Dihydroxy-3-acetyl-6-methyl-9,10 anthraquinone (GXHSWAQ-1) targets mitochondrial proteins (CDH1, RAC1, CDC42) to enhance radiosensitization by altering the mitochondrial structure, including swollen volume, fragmented crista, and decreasing transmembrane potential.144

Furthermore, contrasting evidence points to Drp-mediated mitochondrial fission as an anti-cell death factor. Most recently, Drp1-regulated mitochondrial fission not only promotes the proliferation of tumor cells, but also participates in the maintenance of cell stemness, affecting tumor invasion and metastasis as well as tumor treatment.145 One study has shown that inhibiting Drp1 activity by interrupting the Cox-2/Drp1 axis, reducing the stemness of NPC cells, and helping to increase its sensitivity to resveratrol and 5-flumidine treatment,146 suggesting that targeting Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission would be an effective treatment for NPC. In fact, the involvement of Drp1 in tumor pathogenesis and therapeutic sensitization was also confirmed in our report, demonstrating that mitochondrial fission can be used to classify cancers and play an important role in predicting clinical prognosis and therapeutic response of NPC. Notably, the protein level of p-Drp1 (Ser616) was positively related to the clinical stage of NPC. Patients with a high level of p-Drp1 (Ser616) showed shorter DFS and OS. In contrast, a high level of p-Drp1 (Ser637) in NPC patients is associated with a longer DFS and OS, suggesting that either serine 616 or serine 637 phosphorylation of Drp1 is a prognostic biomarker of NPC patients. What makes more sense is that metformin interrupts the AMPKɑ/ p-Drp1 Ser637 signaling pathway or cucurbitacin E targets the cyclinB1-Cdk1/p-Drp1 (Ser616) axis repressing mitochondrial fission.101 This discovery supports the mitochondrial dynamics markers Drp1 Ser616 and Ser637 as crucial targets for NPC in the future.

Targeting mitochondrial induces apoptosis

Previous studies focusing on the regulation of mitochondria in apoptosis indicated that pro-apoptotic proteins translocate to the mitochondrial outer membrane and trigger the source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis directly.147–149 Interrupting mitochondrial function to induce apoptosis may be a novel mechanism for targeted EBV-associated tumor therapy.

EBV-encoded oncogene BARF1 (BamH1-A Rightward Frame-1) is a survival factor by suppressing apoptosis pathways through modulation of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio. Knock down of BARF1 by siRNA induces mitochondrial-dependent cell death.150 In addition, Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) is the only protein expressed in all three types of latent infection, is also involved in the resistance to mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Triptolide, a diterpene epoxide of the tristeza extract, has been shown to target EBNA1, inhibit proliferation of EBV-positive NPC cells, and induce cell death through a caspase-9-dependent pathway.151 For example, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) is characterized by EBV latent infection with the expression of EBNA1 and LMP1. Importantly, targeting hexokinase domain component 1 (HKDC1), which is highly expressed in ENKTL, is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, EBV replication, and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression.152 The above studies further clarify the role of mitochondria-related cell death in the EBV tumorigenesis process, which will help us to fully understand the molecular mechanism of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of EBV-related tumors, and will be beneficial to the discovery and application of targeted drugs.

Here, we summarize the compounds and gene modification interventions recently associated with mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Pectolinarigenin153 and cinobufagin,154 isolated from an active ingredient in medicinal plants, are novel effective antitumor drug candidates for NPC and mainly inhibit tumor growth by activating mitochondrial-related apoptosis and accumulation of ROS. Bufalin (C24H34O4), a cardiotonic steroid, has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation, decrease the number of total viable cells, and induce G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in NPC-TW 076 cells through ROS-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and TRAIL pathways.155 Celastrol is an effective antioxidant and anti-inflammatory natural compound that inhibits the activity of NPC cells, causes G2/M cycle arrest, and induces mitochondria-related apoptosis.156 Another compound, grape seed proanthocyanidin, has a similar effect in NPC.157 The plant extract, acetogenin, is characterized by a single tetrahydrofuran (THF), which causes G2/M phase arrest, mitochondrial damage and apoptosis, and increases cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels in NPCs.158 This antitumor effect is similar to that of the natural product, tetrandrine (TET).159 An interesting study focusing on an essential trace element showed that Na2SeO3 causes cell cycle arrest and affects the mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic caspase pathway with significant anti-proliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects in CNE-2 NPC cells, suggesting that Na2SeO3 might have therapeutic potential in the treatment of NPC.160 Additionally, human nuclear factor with BRCT domain protein 1 (NFBD1), an amplifier of the p53 pathway and also known as a mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein (MDC1), is vital for protecting cells from apoptosis in NPC cells mediated through the p53-ROS-mitochondrial pathway.161 Liver cancer-1 (DLC-1) is lost at high frequency, mainly due to aberrant promoter methylation, and its tumor suppressor roles are not just limited to liver cancer cells as confirmed in multiple cancers.162 In NPC cells, targeting DLC-1 induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and EMT arrest through the EGFR/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway.163 Generally, the mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein is involved in a variety of biological processes and plays an important role in inflammation, immunity and tumor development.164 One research study revealed that HMGB1 is overexpressed in the HONE-1 NPC cell line and depression of HMGB1 leads to mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis by inhibiting the HMGB1/RAGE pathways165 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Targeted mitochondria-related signaling in NPC

| Targeting molecules | Agents or regulators | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial dynamics | |||

| AMPKɑ/Drp1 | Metformin | Decreases mitochondrial fission and increases chemotherapy sensitivity to cisplatin | 101 |

| CyclinB1-Cdk1/Drp1 | Cucurbitancin E | Decreases mitochondrial fission and increases chemotherapy sensitivity to cisplatin | 101 |

| COX-2/Drp1 | Resveratrol | Inhibits mitochondrial fission and 5-Fu-resistance | 146 |

| TRIAP1 | Knock down | Enhances mitochondrial fission and apoptosis | 143 |

| CDH1, RAC1, CDC42 | GXHSWAQ-1 | Enhances radiosensitisation by altering the mitochondrial structure | 144 |

| Mitochondrial-related cell death | |||

| Bcl-2 | Pectolinarigenin | Inhibits tumor growth by activating mitochondrial apoptosis and accumulation of ROS | 153 |

| Bcl-2 | Cinobufagin | Blocks cells at the S phase, increases intracellular ROS levels, and induces mitochondrial apoptosis pathway | 154 |

| TRAIL | Bufalin | Induces G2/M phase arrest and mitochondrial cell death | 155 |

| MAPK | Celastrol | Triggers G1 and G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and Fas-mediated apoptosis | 156 |

| Bax/Bcl-2 | GSPs | Induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway and ultimately reduces cell viability | 157 |

| c-Jun/ERK | THF-ACGs | Inducers of the ESR that block cell proliferation | 158 |

| Bax, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 | Tetrandrine | Causes G0/G1phase arrest; increases ROS and Ca2+ production and apoptotic cell death | 159 |

| Bax, Bak, Bcl-XL | Na2SeO3 | Inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis | 160 |

| NFBD1/MDC1 | Knock down | Induces apoptosis through the p53/ROS/mitochondrial pathway | 161 |

| DLC-1 | Knock down | Leads mitochondrial apoptosis by targeting EGFR/AKT/NF-κB | 163 |

| HMGB1 | Knock down | Decreases mitochondrial fission and increases chemotherapy sensitivity to cisplatin | 165 |

Mitochondria play an important role in the pathogenesis of tumors by affecting mitochondrial DNA, dynamics, and cell death. The disruption of normal mitochondrial physiology is a hallmark of tumor development. Importantly, EBV- encoded proteins modulate mitochondrial function and thus alter bioenergetics and retrograde signaling pathways to promote tumorigenesis. Therefore, identification of effective mitochondrial molecules and signaling pathways in EBV-associated tumor is essential for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

EBV and the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Ups)

Post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitin (Ub) is a key regulatory event in various cellular activities. Ubiquitination is a dynamic and reversible process, wherein ubiquitin chains are cleaved by deubiquitinase (DUB).166 Ubiquitin signaling comprises three major components of the ubiquitination process known as ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and ubiquitin ligase (E3). E1 activates and transfers ubiquitin to the E2 enzyme and then E2 interacts with the E3 ligase. The E3 ligase binds and transfers ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to target-specific proteins for degradation. The deregulation of the ubiquitin system leads to human pathogeneses, especially cancer. Alterations in the ubiquitin system are known to occur during the initiation and progression of cancer, and this knowledge is starting to be exploited for the development of novel strategies to treat cancer.167

DUBs maintain ubiquitin system homeostasis by cleaving polyubiquitin chains or completely removing ubiquitin chains from ubiquitinated proteins and then generating and recycling free ubiquitin. Deubiquitination also has an important function in regulating ubiquitin-dependent pathways, including cell cycle regulation, cell death, protein degradation, protein function, gene expression, and signal transduction.168,169 Imbalances in DUB activities are involved in multiple diseases, including cancer, inflammation, neurological disorders, and microbial infections. DUB inhibitors (DIs) are becoming potential therapeutic approaches against cancer.170 Most DIs are small-molecular compounds, exerting their function by suppressing DUB activity. Thus far, about 100 DUBs have been identified and classified into two categories, including cysteine proteases and metalloproteases. The cysteine proteases comprise ubiquitin-specific protease (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH), Machado-Josephin domain protease (MJD), ovarian tumor protease (OTU), and motif interacting with Ub-containing novel DUB family (MINDY). The metalloproteases comprise Jab1/Mov34/Mpr1 Pad1 N-terminal (MPN) (JAMM) domain protease.171,172

EBV-encoded proteins and ubiquitin system

All viruses need host machinery to maintain infection and replication. UPS is involved in all aspects of cellular activity. Oncoviruses rely on this system at many levels and even hijack the ubiquitin system to meet their survival needs. The same is also true for EBV. EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) plays important roles in EBV latent gene expression. EBNA1 competitively interacts with the p53 binding site on ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7 (USP7), which is also known as herpes virus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease (HAUSP). The EBNA1 and USP7 interaction can promote cell survival and contribute to EBNA1 functions at the EBV oriP and inhibit p53-mediated antiviral responses.173 EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) can induce the expression of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 (UCHL1) and it may contribute to viral transformation and the progression of lymphoid malignancies.174 EBV early-lytic phase gene BRLF1 encoded Rta, which initial viral gene transcription. Rta can be ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM5a. Overexpression of TRIM5a reduces the transactivating capabilities of Rta, whereas reducing TRIM5a expression enhances EBV lytic protein levels and DNA replication.175

Besides utilizing host DUBs, EBV can also encode the viral deubiquitinating enzyme (v-DUB), BPLF1, which is an immune evasion gene product that can suppress antiviral immune responses during primary infection. BPLF1 is expressed during the late phase of lytic EBV infection and is incorporated into viral particles. It can eliminate K63- and/or K48-linked ubiquitin chains and act as an active DUB during the productive lytic cycle and EBV infection.176

Disturbing of ubiquitin-proteasome system in EBV-related cancer

Cell cycle

Cell cycle regulation is one of the hallmarks of virus-mediated oncogenesis. EBV-encoded LMP1 is an important tumorigenic protein. Unlike many other cancers, p53 is highly expressed in NPC. LMP1 enhances p53 accumulation through two distinct ubiquitin modifications. LMP1 promotes p53 stability by suppressing K48-linked ubiquitination of p53 by E3 ligase murine double minute 2 (MDM2). LMP1 inhibits MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination associated with p53 Ser20 phosphorylation and also induces K63-linked ubiquitination of p53 by interacting with TRAF2, thus disrupting tumor cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.177 Another essential EBV latent protein 3C (EBNA3C) stabilizes Cyclin D2 to regulate cell cycle progression by directly binding to Cyclin D2, and co-localizing together in nuclear compartments.178 EBNA3C interacts with Bcl6 and facilitates its degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent pathway, and suppresses Bcl6 mRNA expression by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of its promoter. EBNA3C-mediated Bcl6 regulation significantly promotes cell proliferation and cell cycle by targeting Bcl2 and CCND1.

During viral lytic replication, EBV protein kinase (PK) phosphorylates p27Kip1 so that it is ubiquitinated by the Skp1/Cullin/F-box protein (SCFSkp2) ubiquitin ligase and degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner. Unlike the cyclin E-CDK2 activity, the EBV PK activity is not inhibited by p27Kip1. Overall, EBV possesses its own strategy to degrade p27Kip1 upon onset of productive replication, contributing to provision of an S-phase-like cellular environment with high CDK activity.179

Cell death

Cell death is a critical component of the host immune response against invading microbial pathogens. As is discussed above, EBV-LMP1 disrupting tumor cell apoptosis through p53. EBV is also capable of preventing necroptosis. Necroptosis is a relatively newly discovered pathway of programmed cell death, the deregulation of which is related to various inflammatory diseases and cancer.180 LMP1 is armed with mechanisms independent of the RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM)-domain interactions to block necroptosis. First, LMP1 is able to interact with both receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) and receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) by C-terminal activation region 2 (CTAR2), which is necessary for this interaction. Breaking the combination of RIPK1 and RIPK3 inhibits the formation of necrosomes. Second, and more importantly, the ubiquitination of the two receptor-interacting proteins can be modulated by LMP1. LMP1-mediated promotion of K63-polyubiquitinated RIPK1, suppression of RIPK1 protein expression, and inhibition of K63-polyubiquitinated RIPK3 induces a switch in cell fate from necroptotic death to survival.181

DNA damage

DNA damage signaling and repair pathways are important determinants of both cancer development and cancer therapy. EBV nuclear protein expressed in gastric carcinomas (GC), EBNA1, focusing on promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies (NBs), which play important roles in apoptosis, p53 activation. EBV infection of GC cells leads to degradation of PML NBs through the action of EBNA1 interacting with USP7, resulting in impaired responses to DNA damage and promotion of cell survival. Therefore, PML disruption by EBNA1 is one mechanism by which EBV may contribute to the development of gastric cancer.182 O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a key DNA repair enzyme contributing to the chemoresistance, which protects NPC cells from DNA damage by enhancing the capacity for DNA repair.183 Research findings showed that ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 B (UBE2B) collaborates with E3 ubiquitin ligase RAD18 to mediated MGMT ubiquitination and degradation.184 Rad18 is also responsible for monoubiquitination of PCNA, which initiates several cellular DNA repair processes. V-DUB BPLF1 targets ubiquitinated PCNA and disrupts trans-lesion synthesis (TLS). Deubiquitination of PCNA by the viral DUB can disrupt repair of DNA damage by compromising recruitment of TLS polymerase to stalled replication forks.185 BPLF1 interacts directly with Rad18, and overexpression of BPLF1 results in increased levels of the Rad18 protein, suggesting that it stabilizes Rad18. Next, expression of functionally active BPLF1 causes relocalization of Rad18 into nuclear foci, which is consistent with sites of cellular DNA replication that occur during S phase, which contributes to virus replication and infectivity.186 Transcription factor p53 is a critical mediator that is directly phosphorylated and stabilized by DNA damage signaling kinases, which triggers the apoptotic program.187 Zhang et al.188 found that RING-finger domain-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase tripartite motif–containing 21 (TRIM21) repressed p53 expression by mediating guanine monophosphate synthase (GMPS) ubiquitination and degradation. TRIM21 protects NPC cells from radiation-induced apoptosis by manipulating the GMPS–p53 cascade.188 In addition, TRIM21 is also responsible for the polyubiquitination of prohibitin 1 (PHB1), a pleiotropic protein that functions as a tumor suppressor. Ubiquitination and degradation of PHB1 leads to transcriptional activation of NF-κB and STAT3.189 TRIM21 mediates small G-protein signaling modulator 1 (SGSM1) ubiquitination degradation and inhibits the MAPK pathway activation.190 Deubiquinase ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) from the UCH family forms complexes with p53/MDM2/ARF and deubiquitinates p53 promoting p53 signaling, which is involved in NPC pathogenesis.191

Akt signaling

Deregulation of protein kinase B (Akt) signaling plays a vital role in the regulation of tumorigenesis in human cancers.192 K63-linked ubiquitination of Akt is required for Akt membrane translocation and activation.193 E3 ligase S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) overexpression is correlated with poor prognosis in NPC patients, Skp2-mediated ubiquitination and mitochondrial localization of Akt drive tumor growth and resistance to cisplatin.194,195 TNF-receptor-associated factor (TRAF) proteins are key adaptor molecules containing E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, which plays a critical role in multiple cell signaling pathways. TRAF6 binds to and ubiquitinates Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), a complex transcription factor that acts as a tumor-promoting gene in NPC. This leads to KLF4 K32/K63-linked ubiquitination and stabilization, which results in NPC196 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

EBV-encoded proteins modulate host ubiquitin signaling pathways. EBV regulates degradation and non-degradation ubiquitination of key molecules in cell signaling pathways through hijacking host ubiquitinase and deubiquitinase, or directly encoding viral deubiquitinase. The ubiquitinases in orange cycle represents activated by EBV protein, and the gray represents for suppressed ubiquitinase

The natural compound, neoalbaconol, targets the ubiquitin system in EBV-related cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is emerging as a novel target for anticancer drugs and molecular diagnostics.197 Escape from programmed cell death plays a critical role in cancer. Therefore, investigating the role of necroptosis in cancer has been of high interest. We found that necroptosis is one of the major cell death forms induced by neoalbaconol. Natural compounds derived from plants, fungi, and marine organisms are widely used as anticancer drugs in preclinical/clinical development or in clinic.105 Neoalbaconol down-regulates E3 ubiquitin ligases cellular inhibitors of apoptosis protein 1/2 (cIAP1/2) and TRAFs to abolish K63-linked ubiquitination on RIPK1.198 This induces the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway and increases the transcription activation of TNFα. Moreover, neoalbaconol induces RIPK3-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production that participates in necroptosis.198 RIPK1/NF-κB-dependent TNFα secretion and RIPK3-dependent ROS generation contribute to neoalbaconol-induced necroptosis.

Ubiquitinases and deubiquitinases are emerging as potential therapeutic targets in many diseases, especially cancer. In this chapter, we summarize the involvement of these enzymes in cancer signaling and cell regulation and illustrate the potential role of the ubiquitin system in response to cancer therapeutics (Table 5). We also discussed how the onco-virus EBV fights with the host by utilizing host ubiquitin signaling or even encoding v-DUB to hijack host cellular processes. Deciphering the various functions of ubiquitinases and deubiquitinases will be challenging but should help provide a greater understanding of how its deregulation results in tumorigenesis and development. As for the potential therapeutic targets, the ultimate challenge is to translate these basic research findings into novel and more effective cancer therapies.

Table 5.

Ubiquitinase in EBV-related tumorigenesis

| Type | Enzyme | Target | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin E3 ligase | UBE2B | MGMT | Chemoresistance | 184 |

| RAD18 | MGMT | Chemoresistance | 184 | |

| TRIM21 | GMPS | Apoptosis inhibition | 188 | |

| PHB1 | Cell proliferation | 189 | ||

| SGSM1 | MAPK pathway activation | 190 | ||

| Skp2 | Akt | Chemoresistance and cell proliferation | 193 | |

| TRAF6 | KLF4 | Tumorigenesis | 196 | |

| TRAF2 | P53 | Disrupting tumor cell apoptosis | 177 | |

| TRIM5a | Rta | Inhibit EBV lytic replication | 175 | |

| Deubiquintylase | UCHL1 | p53 | Tumorigenesis | 191 |

| USP7 | p53 | Inhibit antiviral responses | 173 | |

| v-Deubiquintylase | BPLF1 | PCNA | Disrupt repair of DNA damage | 185 |

Oxidative stress in EBV-associated diseases

The regulation of redox homeostasis is fundamental to maintaining normal cellular functions and ensuring cell survival. Cancer cells are characterized by increased aerobic glycolysis and high levels of oxidative stress.199 This oxidative stress is exerted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that accumulate as a result of an imbalance between ROS generation and elimination.200 ROS are constantly produced by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions.200 Enzyme-catalyzed reactions that generate ROS include those involving NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), arachidonic acid and metabolic enzymes such as the cytochrome P450 enzymes, lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase. The mitochondrial respiratory chain is a non-enzymatic source of ROS.200 The produced ROS include superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen and reactive nitrogen species. Usually, determination of cellular redox status by a balance between levels of ROS inducers and ROS scavengers. The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be induced by hypoxia, metabolic defects, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and oncogenes. Conversely, ROS are eliminated by the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), the production of glutathione and NADPH, the activity of tumor suppressors (such as breast cancer susceptibility 1 (BRCA1), p53, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)) and the action of dietary antioxidants.200 Nowadays, many compounds have been described as antioxidants. These include compounds with free sulfhydryl groups, including N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and lipoic acid, compounds with multiple double bonds and conjugation (e.g., carotenoids, tocopherols and retinoids, among others) and polyphenols (e.g., epicatechingallate and quercetin, among others). Compounds that inhibit reactive oxygen generation (i.e., NADPH oxidase inhibitors), xanthine oxidase inhibitors and compounds that induce oxidant defenses (e.g., Nrf2 activation-sulforaphane, among others) have also been allocated to this category.201

ROS-mediated oxidative stress has an increasingly well-recognized broad function in oncogenesis.202 Generating oxidative stress is a critical mechanism by which host cells defend against infection by pathogenic microorganisms.203 Several reports have shown that both DNA and RNA viruses can lead to oxidative stress by encoding various products and play roles in virus survival. For example, HBV encoded HBx204 and HSV-1 encoded UL12.5205 can induce oxidative stress by degradation of mtDNA; KSHV encoded Rac-1206 and HIV encoded Gp120, Tet or Nef207 can induce oxidative stress by regulating the NOX pathway.

EBV, a member of γ-herpesviruses, is an important cancer causing virus.4 NPC is an infection-associated cancer strongly driven by EBV.11,208 So far, several evidences showed increased levels of ROS in cells and in NPC patients. In vitro, EBV infection can induce an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and decreases in catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between BZLF1 and antioxidant enzyme genes expression, which also confirmed a role of EBV lytic reactivation in oxidative stress.209 Notably, reactive oxygen signaling can distinguish EBV-positive versus EBV-negative tumors based on the finding that elevated levels of ROS are observed in EBV-positive tumors but not in EBV-negative tumors.210 On the other hand, oxidative stress inducers, such as H2O2 or FeSO4, can cause EBV lytic cycle induction as demonstrated by BZLF1 gene expression.211 Moreover, various drugs that induce or inhibit EBV lytic reactivation also act by generating oxidative stress.212,213 Thus, a vicious cycle could be initiated whereby reactivation of EBV and ROS production amplify each another. In vivo, overexpression of iNOS and the accumulation of 8-OHdG, critical biomarkers of oxidative stress, were found in NPC patients.214,215 Huang et al.216 detected the serum 8-OHdG using ELISA in NPC patients and found that all cases of NPC were positive for 8-OHdG and therefore, 8-OHdG is proposed as a potential biomarker for evaluating the risk of NPC. Su et al.217 observed decreased SOD activity in NPC that is consistently associated with EBV. These observations indicate that NPC biopsies present a high level of oxidative stress.

Moreover, other EBV-associated tumors also present high levels of oxidative stress. For instance, Cerimele et al.210 demonstrated that EBV-positive BL expresses high levels of activated mitogen-activated protein kinase and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and that ROS directly regulate NF-κB activation. In EBV-associated gastric cancers, Kim et al.218 reported EBV induces high levels of oxidative stress and thus regulates cell viability.

Additionally, it is reported that several EBV-encoded products, including EBNA1, LMP1, and EBER are associated with oxidative stress. Possible mechanisms by which EBNA1 could induce ROS, include increasing levels of oxidases (e.g., NOX1 and NOX2) or affecting the levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD1, peroxiredoxin 1, peroxiredoxin 6, or glutathione S-transferase.16,219,220 The mechanism of inducing oxidative stress by LMP1 was via activating of NOX2 and Nrf2 pathway (unpublished data). EBER that induces interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-10 has been implicated in the activation of mitochondrial ROS.210 Based on the reported preclinical and clinical evidence, it is indicated the oxidative stress is involved in EBV infection.

Bonner et al.201 has classified tumors by signaling pathways and proposed a concept of ROS-driven tumors. So far, several types of tumors have been classified into reactive oxygen species (ROS)-driven tumors and include EBV-associated Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, gastric carcinoma, hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma, ultraviolet A-induced melanoma, inflammatory bowel disease-induced colon carcinoma, schistosomiasis-induced bladder cancer, tobacco-induced oral and lung carcinoma, and epidermolysis bullosa-associated squamous cell carcinoma. These cancers are characterized by activation of high expression levels of NF-κB, Akt and wild-type p53 and PTEN.201 According to the signaling events in the reactive oxygen-driven tumor and the fact of high oxidative stress in NPC, it is proposed that NPC is a reactive oxygen-driven tumor.

Regarding to the important role of ROS in EBV-associated diseases, the monitoring and detection of ROS is vital important to the therapy of EBV-related malignancies. So far, there are several ways to detect the level of intracellular oxidative stress. (a) Total ROS level (combined with ROS dye by flow cytometry); (b) mitochondria ROS level (using flow cytometry combined with mitochondrial-specific ROS dye MitoSox red); (c) intracellular NADP+/NADPH ratio (NADP+/NADPH kit); (d) intracellular GSSG/GSH ratio (GSSG/GSH kit); (e) Expression and activity of oxidoreductase. For the detection of oxidative stress level of tumor patients, pathological samples and serum samples can be collected, which can be reflected by detecting the content of oxidative stress marker 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). 8-OHdG is one of the most common DNA damage products in response to oxidative stress, and has been recognized as a reliable and stable biomarker of oxidative stress.221,222 The level of 8-OHdG in tissue samples is positively correlated with the degree of oxidative stress, so the level of 8-OHdG in blood or pathological tissue samples can be detected by ELISA or immunohistochemistry to reflect the degree of oxidative stress.