Abstract

The current management of patients with primary psychosis worldwide is often remarkably stereotyped. In almost all cases an antipsychotic medication is prescribed, with second‐generation antipsychotics usually preferred to first‐generation ones. Cognitive behavioral therapy is rarely used in the vast majority of countries, although there is evidence to support its efficacy. Psychosocial interventions are often provided, especially in chronic cases, but those applied are frequently not validated by research. Evidence‐based family interventions and supported employment programs are seldom implemented in ordinary practice. Although the notion that patients with primary psychosis are at increased risk for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus is widely shared, it is not frequent that appropriate measures be implemented to address this problem. The view that the management of the patient with primary psychosis should be personalized is endorsed by the vast majority of clinicians, but this personalization is lacking or inadequate in most clinical contexts. Although many mental health services would declare themselves “recovery‐oriented”, it is not common that a focus on empowerment, identity, meaning and resilience is ensured in ordinary practice. The present paper aims to address this situation. It describes systematically the salient domains that should be considered in the characterization of the individual patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. These include positive and negative symptom dimensions, other psychopathological components, onset and course, neurocognition and social cognition, neurodevelopmental indicators; social functioning, quality of life and unmet needs; clinical staging, antecedent and concomitant psychiatric conditions, physical comorbidities, family history, history of obstetric complications, early and recent environmental exposures, protective factors and resilience, and internalized stigma. For each domain, simple assessment instruments are identified that could be considered for use in clinical practice and included in standardized decision tools. A management of primary psychosis is encouraged which takes into account all the available treatment modalities whose efficacy is supported by research evidence, selects and modulates them in the individual patient on the basis of the clinical characterization, addresses the patient’s needs in terms of employment, housing, self‐care, social relationships and education, and offers a focus on identity, meaning and resilience.

Keywords: Primary psychosis, schizophrenia, personalization of treatment, psychosocial interventions, recovery, positive dimension, negative dimension, neurocognition, social cognition, social functioning, psychiatric antecedents, psychiatric comorbidities, physical comorbidities, family history, obstetric complications, environmental exposures, protective factors, resilience, practical needs, internalized stigma

Primary psychoses represent a heterogeneous group of mental disorders that: a) are characterized by delusions and/or hallucinations, along with other clinical manifestations such as disorganized thinking, grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms (i.e., affective blunting, alogia, asociality, anhedonia or avolition); b) are not due to the effects of a substance or a medication on the central nervous system, and are not secondary to another medical condition (e.g., a brain tumor or an autoimmune disease) or a mood disorder (depression or mania).

Our current diagnostic systems, the DSM‐51 and the ICD‐11 2 , include several categories that fulfill the above definition, but neither the list of these categories nor their definition is consistent between the two systems.

In the DSM‐5, primary psychoses include schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, “other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder”, and “unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder”. In the ICD‐11, primary psychoses (the expression “primary psychotic disorders” is explicitly used in this system) include schizophrenia, acute and transient psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and “other primary psychotic disorder”.

In the DSM‐5, the definition of schizophrenia requires that “continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months”, whereas this requirement is absent in the ICD‐11 (it is only stated that “symptoms must be present most of the time for a period of one month or more”). As a consequence of this, the DSM‐5 category of schizophreniform disorder (marked by a duration of the disorder of at least one month but less than six months) does not appear in the ICD‐11. People with a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder according to the DSM‐5 will be diagnosed as having schizophrenia according to the ICD‐11.

Furthermore, social dysfunction is an integral part of the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia in the DSM‐5 (“for a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, level of functioning in one or more major areas, such as work, interpersonal relations, or self‐care, is markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset”) 1 , whereas this element is absent in the ICD‐11 definition. In the “additional features” subsection of the section on schizophrenia of the ICD‐11 diagnostic guidelines, it is indeed specified that “distress and psychosocial impairment are not requirements for a diagnosis of schizophrenia” 2 .

The symptomatological criterion for the diagnosis of schizophrenia lists, in both the DSM‐5 and ICD‐11, delusions, hallucinations, negative symptoms, disorganized thinking, and grossly disorganized behavior. However, the ICD‐11 also includes “experiences of influence, passivity or control” (subsumed under the heading of delusions in the DSM‐5), and “psychomotor disturbances” (which are part of the item “grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior” in the DSM‐5).

Schizoaffective disorder is defined quite differently in the two diagnostic systems. In fact, the longitudinal criterion (“delusions or hallucinations for two or more weeks in the absence of a major mood episode (depressive or manic) during the lifetime duration of the illness”) is absent in the ICD‐11, in which the disorder is just defined by the concurrent fulfillment of the definitional requirements for schizophrenia and a mood episode for at least one month. So, a number of patients will receive a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder according to the ICD‐11 but not the DSM‐5.

There are also significant differences in the DSM‐5 definition of brief psychotic disorder vs. the ICD‐11 characterization of acute and transient psychotic disorder. In particular, the presence of negative symptoms is excluded in the definition of the latter but not the former disorder, and the duration of symptoms is required to be “less than one month” in the DSM‐5, while it “does not exceed three months” in the ICD‐11. Furthermore, the requirement that “symptoms change rapidly, both in nature and intensity, from day to day or even within a single day” is present in the ICD‐11 definition but not in the DSM‐5 criteria.

Also due to the above discrepancies, that were already present in the previous editions of the two diagnostic systems, there is no clarity about the prevalence of the individual primary psychotic disorders either in the general population or in clinical settings. What can certainly be argued is that there is a predominant focus on schizophrenia both in research and in clinical practice. For instance, research on neurocognitive impairment has been conducted almost exclusively in patients with a post‐DSM‐III diagnosis of schizophrenia 3 , and its results may not be generalizable to all patients with an ICD‐11 diagnosis of schizophrenia or to patients with ICD‐11 “other primary psychotic disorder”.

On the other hand, the awareness that the term schizophrenia has been traditionally associated with the notion of a poor outcome, and has acquired in ordinary language a derogatory connotation 4 , is leading many clinicians and researchers to use the generic term “psychosis” as a synonym for schizophrenia or as equivalent to the expression “primary psychosis”. This is generating confusion in the field – e.g., obscuring the need for the differentiation between primary psychosis and substance induced psychosis.

Of note, one of the few comprehensive population‐based epidemiological studies available in this area (which used DSM‐IV criteria, that are very close to DSM‐5 ones) 5 found the lifetime prevalence of all primary psychotic disorders to be 1.94%, while that of schizophrenia was 0.87% (so, according to this study, schizophrenia accounts for just 43.8% of cases of primary psychotic disorder). The lifetime prevalence was 0.32% for schizoaffective disorder, 0.07% for schizophreniform disorder, 0.18% for delusional disorder, 0.05% for brief psychotic disorder, and 0.45% for psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. The lifetime prevalence of affective psychoses was 0.59%, that of substance induced psychotic disorder was 0.42%, and that of psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition was 0.21% (so that schizophrenia accounted for only 26.9% of all cases of psychotic disorder) 5 .

The current approach to schizophrenia (or to “psychosis”) in routine clinical practice worldwide is often remarkably stereotyped. In almost all cases an antipsychotic medication is prescribed, with second‐generation antipsychotics usually preferred to first‐generation ones 6 . Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is rarely used in the vast majority of countries, even though there is evidence to support its efficacy 7 . Psychosocial interventions are often provided, especially in patients with chronic illness, but those applied are frequently not validated by research 8 . Evidence‐based family interventions 9 and supported employment programmes 10 are seldom implemented in ordinary practice. The notion that patients with schizophrenia (or “psychosis”) are at increased risk for several physical diseases and that their life expectancy is dramatically reduced is now widely shared, but it is not frequent that appropriate measures be implemented to address this problem as part of the management plan 11 .

The view that the management of a patient with schizophrenia (or “psychosis”) should be personalized is endorsed by the vast majority of clinicians, but the awareness that this would require a comprehensive assessment of the patient, beyond the mere diagnosis, is not equally shared, and personalization of management is actually lacking or inadequate in most clinical contexts worldwide 12 .

Finally, although many mental health services would declare themselves “recovery‐oriented”, in practice a resilience‐promoting environment is rarely provided, and a focus on the skills that people with primary psychosis need to learn in order to live a fulfilling life despite persistent disabilities is not common 13 .

The present paper, which has been produced in parallel with a similar one focusing on depression 14 , aims to address the situation we have just described. Its main objectives are: a) to reinforce the emerging awareness of the need to personalize the management of patients with primary psychosis, taking into account all the available treatment modalities whose efficacy is supported by research evidence; b) to help in the identification of the salient domains to be considered in the characterization of the individual patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management (see Table 1); c) to help in the selection of simple assessment instruments that can already be considered for use in clinical practice today, and can be included in comprehensive batteries of measures to be tested in large observational studies in order to guide the development of standardized decision tools 15 ; and d) to encourage a clinical practice that is recovery‐oriented as well as evidence‐based.

Table 1.

Salient domains to be considered in the clinical characterization of a patient with a diagnosis of primary psychosis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the basis of the above discussion, we will preferentially use the expression “primary psychosis” throughout the paper, except in those cases in which the available research evidence specifically refers to patients with a post‐DSM‐III diagnosis of schizophrenia.

We are fully aware that a significant effort is ongoing to identify biological measures or markers that may help in the personalization of the management plan in patients with primary psychosis. However, since none of these measures or markers is currently ready for use in clinical practice, we do not consider them in this paper. On the other hand, we do believe that biological research can benefit from a systematic characterization of patients with primary psychosis, since this is likely to facilitate the identification of more homogeneous subtypes within this group of disorders.

POSITIVE DIMENSION

The conceptualization of the positive dimension as the core of primary psychosis has continuously evolved over the last four decades. There is common agreement that this dimension includes delusions (persistent false beliefs based on an incorrect inference about reality, that are firmly maintained despite obvious contrary evidence, and are not shared by others with a similar cultural background) and hallucinations (perception‐like experiences with the clarity and impact of a true perception but without the external stimulation of the relevant sensory organ). Other symptoms – i.e., disorganized thinking (covered in another section of this paper) and self‐disturbances – are sometimes regarded as part of this dimension.

Self‐disturbances are alterations in the sense of self as the subject of one’s experience and agent of one's actions 16 . They have been hypothesized by some authors to represent the “core Gestalt” of schizophrenia 17 . Empirically, there is evidence for the validity and relevance of self‐disturbances from studies using the Examination of Anomalous Self‐Experience (EASE) 18 : EASE scores are increased in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia compared to those with other mental disorders 19 . Anomalous self‐experiences have been reported to be among the most common symptoms in the prodromal phase of primary psychosis, and scores on the Inventory of Psychotic‐Like Anomalous Self‐Experiences (IPASE)20, 21, a self‐report measure of minimal self‐disturbances, have been found to correlate with those for subclinical positive symptoms as assessed by the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental States (CAARMS) 22 and the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE) 23 .

In the ICD‐112 (but not in the DSM‐5 1 ), “experiences of influence, passivity or control” are regarded as a separate symptom from delusions. If these experiences are explained in a delusional manner, then the presence of both these experiences and delusions should be recorded.

The ICD‐11 and DSM‐5 provide a dimensional assessment of positive symptoms beyond the categorical classification. The ICD‐11 enables clinicians to indicate the severity of positive symptoms in patients with primary psychosis using a symptom qualifier, with scores ranging from “0 ‐ not present” to “3 ‐ present and severe”, based on patient report or observer rating during the last week. This qualifier combines hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking and behavior, and experiences of influence, passivity and control to an overall score indicating the severity of the positive dimension. The ICD‐11 also specifies degrees of severity for each of those four symptoms. The DSM‐5 contains dimensions of psychosis symptom severity covering hallucinations, delusions and disorganized speech (each rated on a 5‐point scale). These measures help to improve clinical decision‐making beyond the diagnostic categories and allow the monitoring of course and outcome.

The positive scale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) 24 is the most widely used instrument for the assessment of positive symptoms. The PANSS allows clinicians to rate the severity of seven positive symptoms (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, excitement, grandiosity, suspiciousness/persecution, and hostility), each on a 7‐point scale ranging from “1 ‐symptom not at all present” to “7 ‐ symptom extremely severe”. For these ratings, information from a clinical interview and, if available, other sources (e.g., family members) is used. There is a large body of evidence indicating good reliability, validity and sensitivity of the PANSS 25 , which is available in several languages. However, the scale contains items that are not clearly part of the positive dimension of primary psychosis (e.g., hostility and excitement).

The PANSS‐6 26 , an abbreviated version of the PANSS that could be more suitable for use in routine clinical practice, contains a subscale including three items that refer to the positive dimension of primary psychosis: delusions, hallucinations and conceptual disorganization.

Across different instruments and classification systems, clinicians should resort to different sources of information to assess positive symptoms in primary psychosis (i.e., self‐report, clinical observations, information provided by care staff or family members). Integrating these sources is particularly necessary when information about longer time periods is required (e.g., to assess whether a person meets the time criterion of six months for schizophrenia according to the DSM‐5).

Depending on the illness stage, people with primary psychosis are usually able to reliably report positive symptoms 27 . The assessment of these symptoms may be more problematic in patients lacking insight, where it can be facilitated by the technique of “Socratic questioning” 28 , a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw out ideas and underlying presuppositions.

The presence of positive symptoms has immediate consequences for an integrated management plan. On the pharmacological side, antipsychotic drug treatment is strongly recommended for people with acute positive symptoms. Although there may be differences among the various antipsychotic drugs regarding their efficacy on positive symptoms 29 , these are not sufficiently clear to guide the clinician’s choice in the individual case, which is usually based essentially on issues concerning possible side effects. The assessment of the severity of positive symptoms over time, using one of the above‐mentioned tools, is crucial to monitor their evolution and to lead, if treatment resistance emerges 30 , to the prescription of clozapine.

In patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, antipsychotic maintenance treatment (i.e., continuous treatment with the lowest effective dose of oral or long‐acting antipsychotic medication) is recommended to prevent relapse 31 , although there is not a consensus about how long this treatment should be continued32, 33, due to the lack of randomized controlled trials beyond the second year following the first psychotic episode.

Particularly in acute stages with limited judgement, delusional loss of reality control, and lack of coping with everyday life, positive symptoms may require inpatient care. Close monitoring of positive symptoms and a corresponding adjustment of medication or inpatient admission is always required, in the framework of a person‐oriented, individualized and human‐rights respecting approach of evidence‐based treatment and care.

CBT, in addition to antipsychotic medication, can produce further improvement in positive symptomatology for people with primary psychosis 7 . Considering the type and severity of positive symptoms is crucial to tailor the psychotherapeutic approach accordingly, for example in the presence of disorganized thinking 34 . There are also effective psychotherapeutic interventions for specific positive symptoms (e.g., cognitive therapy for command hallucinations) 35 . Family interventions, including illness education and crisis intervention, can lower the levels of distress and burden associated with positive symptoms in primary psychosis 9 .

Positive symptoms have been reported to be associated with cognitive biases, which can be addressed in psychoeducation and may be targeted in CBT. The Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for psychosis (CBQp) 36 measures five specific cognitive biases: jumping‐to‐conclusions (making firm decisions based on little evidence), intentionalizing (interpreting events or behaviors as deliberate), catastrophizing (worst‐case‐scenario thinking), emotional reasoning, and dichotomous (i.e., “black or white”) thinking.

NEGATIVE DIMENSION

Negative symptoms have long been conceptualized as a core aspect of primary psychosis, especially schizophrenia37, 38, and their treatment is increasingly recognized as an important unmet need. They play a key role in the functional outcome of the disorder39, 40, and largely contribute to the burden that the disorder poses on affected people, their relatives and the society 41 . Unfortunately, so far, most available treatments have shown a limited impact on these symptoms, especially when they are primary and persistent.

According to recent studies and expert opinions41, 42, 43, 44, negative symptoms include five domains, also known as the 5 As: affective blunting, alogia, asociality, anhedonia and avolition.

Affective blunting, more often referred to as blunted affect, is a reduction in the expression of emotion and reactivity to events. It is assessed during the clinical interview by inspecting spontaneous or elicited changes in facial and vocal expressions, as well as the amount of expressive gestures. In the assessment of blunted affect, clinicians should avoid a quite common mistake, i.e. the tendency to include the subjective experience of decreased emotional range or a general decrease in spontaneous movements, as these aspects are non‐specific and more relevant to depression.

Alogia refers to a reduction in the quantity of spoken words and the amount of information spontaneously given when answering a question. The person with alogia provides very short answers, with few words strictly needed to answer the question. The poverty of content of speech in the presence of a normal quantity of spoken words is not included in the alogia construct, but is part of the disorganization dimension.

Asociality is a reduction in social interactions and initiative due to indifference or lack of desire for them. The clinician should investigate both the behavioral aspect (e.g., the reduction of interpersonal relationships) and the decreased interest in social bonds.

Anhedonia should be further characterized as consummatory or anticipatory. The former is a reduction in the experience of pleasure during pleasurable activities. The latter involves a reduction in the anticipation of pleasure for future pleasurable activities.

Avolition, also referred to as amotivation or apathy, refers to a poor engagement in any activity due to a lack of interest and motivation. It is important that the examiner evaluates both subject’s behavior and internal experience. The clinician can be confident about the presence of avolition when behavior shows poor engagement in activities and the subject does not miss or feel the need to participate in those activities.

From a clinical standpoint, it is important to distinguish primary from secondary negative symptoms. Currently, this distinction remains a major challenge. Suggestions provided hereafter are meant to support clinicians in this effort.

Primary negative symptoms are supposed to stem from the pathophysiological process underlying psychosis. They are often persistent across the different stages of the disorder 45 , and do not show a substantial improvement with most treatments available so far. The only head‐to‐head study supporting the superiority of an antipsychotic drug to treat primary negative symptoms compared cariprazine with risperidone and found the former to be more effective 46 . However, the study was sponsored by the manufacturer and no independent replication is available so far. Results provided by trials exploring the efficacy of drugs with mechanisms different from D2 antagonism or D2/D3 partial agonism (e.g., glutamatergic or dopamine agonists) remain inconclusive 41 .

When signs and symptoms resembling negative symptoms are due to other illness dimensions, in particular positive symptoms, depression, extrapyramidal symptoms, sedation, environmental deprivation, or substance use, they are referred to as secondary negative symptoms. In this case, they can improve when the underlying factors are correctly identified and adequately treated.

In case of negative symptoms secondary to positive symptoms, patients may be reluctant to talk and interact with the examiner. They (or others) may report an asocial behavior due to persecutory delusions and/or difficulties in initiating and persisting in goal‐directed activities due to engagement in delusional thinking or abnormal perceptions. If this is the case, clinicians should treat positive symptoms aiming at their remission, by using adequate doses of antipsychotics, improving adherence to treatment, and prescribing clozapine in case of failure with at least two other antipsychotics. When treatment leads to an improvement of psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms often improve as well.

Depression may also underlie secondary negative symptoms, such as a reduced range of emotional expression, diminished amount of speech, social withdrawal, anhedonia and lack of motivation. The co‐occurrence of sadness, feelings of guilt, and suicidal ideation or attempts strongly suggests that these features are due to depression. In this case, treatment with second‐generation antipsychotics should be preferred to first‐generation medications, which could worsen depression, and add‐on treatment with antidepressants should be considered.

Side effects of antipsychotic drugs, in particular high doses of first‐generation antipsychotics, may also produce secondary negative symptoms: akinesia or bradykinesia, for instance, can result in reduced expression and amotivation, due to reduced dopaminergic transmission. The presence of other extrapyramidal side effects (tremor or rigidity, gate instability) can confirm this interpretation and indicate the need to reduce the doses or change the class of antipsychotics (e.g., switching from first‐ to second‐generation drugs or to a D2/D3 partial agonist).

Among non‐pharmacological interventions for negative symptoms, preliminary evidence of beneficial effects of social skills training, CBT and cognitive training is available. In particular, there is evidence of superior efficacy of social skills training vs. treatment as usual and active comparators47, 48. The evidence for CBT is weaker, and trials in large samples of patients with severe negative symptoms, based on CBT approaches specific for those symptoms, are needed47, 49. Cognitive training, although primarily aimed to treat cognitive dysfunctions, seems to have small to moderate beneficial effects on negative symptoms too 50 . However, a certain degree of overlap between cognitive dysfunctions and negative symptoms does remain, and makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions on the efficacy of this intervention for negative symptoms.

Available evidence also suggests that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the left prefrontal region may possibly be an effective treatment for patients with negative symptoms that do not improve with other interventions 51 .

The relevance of the above non‐pharmacological treatments to primary and persistent negative symptoms remains to be tested in controlled trials.

The most widely used instruments for the assessment of negative symptoms are the PANSS 24 and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) 52 . However, the use of these tools is problematic, due to the inappropriate inclusion of symptoms that are not relevant to the negative dimension (e.g., difficulty in abstract thinking and stereotyped thinking in the PANSS).

Two state‐of‐the‐art instruments, the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS) 53 and the Comprehensive Assessment of Negative Symptoms (CAINS) 54 , are increasingly used in research settings, but unfortunately their dissemination to clinical practice is still limited. Neither scale contains irrelevant items; both focus on inner experience in addition to behavioral aspects, and allow the assessment of anticipatory and consummatory anhedonia. For both instruments, training is advisable and can be conducted online.

The BNSS consists of 13 items covering the five domains of blunted affect, alogia, asociality, anhedonia and avolition. The scale has been found to have an excellent inter‐rater and test‐retest reliability and a strong internal consistency 53 . The CAINS also has 13 items, loading on two modestly correlated subscales: expression and motivation/pleasure. The former has been found to be related to independent living and family functioning, while the latter has been related to all aspects of functioning. The inter‐rater and test‐retest reliability of the tool has been documented 54 .

Clinicians often express the desire for an instrument specifically designed for clinical assessment, and taking less time than either BNSS (about 20 min) or CAINS (about 35 min). Unfortunately, for the time being, no tool is available that provides an accurate and at the same time shorter assessment of negative symptoms.

OTHER PSYCHOPATHOLOGICAL COMPONENTS

Psychopathological components of primary psychosis other than positive and negative symptoms include disorganization, motor disturbances, mood states, and lack of insight.

The disorganization component of primary psychosis comprises positive formal thought disorders (thought disorganization), bizarre behavior, and inappropriate affect. From a network perspective, disorganization has been reported to be the most central and interconnected domain of psychotic disorders 55 . It is strongly related to neurocognition and represents an integral link in cognitive pathways 56 , although this association may be due to some conceptual overlap with neuropsychological constructs such as abstraction and attention. Formal thought disorders appear to be the psychotic symptoms whose contribution to everyday functioning is most significant 57 .

There is a lack of specific instruments for assessing the various subcomponents of disorganization, yet they can be reliably derived from wide‐ranging scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) 58 and the Manual for Assessment and Documentation of Psychopathology (AMDP) 59 . Formal thought disorders, the core manifestations of disorganization, are reliably evaluated by the positive formal thought disorder subscale from the CASH and, more comprehensively, by the Thought, Language and Communication (TLC) rating scale 60 .

Disorganization symptoms tend to co‐vary with positive symptoms during acute psychotic episodes, and with negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. There is no specific pharmacological treatment for these symptoms, although they respond well to antipsychotic medication during the acute phases of primary psychosis. In chronic stages, disorganization symptoms appear to be better addressed by psychosocial rehabilitation programs, although controlled trials thereof are lacking.

Motor abnormalities comprise a broad array of manifestations that are usually subdivided into two overlapping subdomains: catatonia and extrapyramidal signs (EPS). EPS are usually linked with side effects of antipsychotics; however, they may also be an indigenous feature of primary psychosis, the so‐called spontaneous EPS, which are tied to the underlying pathophysiology of the illness. Spontaneous EPS are observed in 15‐25% of drug‐naïve subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorders; hence, it would be useful to assess motor abnormalities before and after starting antipsychotic medication, to disentangle their primary or secondary origin. Such a differentiation, however, may be challenging even for experienced clinicians. Currently, a balanced view of motor signs in subjects on antipsychotics is that they result from an interaction between medication and illness‐related factors 61 .

Motor signs are poorly represented in the assessment instruments for psychosis; thus, it is necessary to make use of specific tools. For catatonia, the Bush‐Francis Catatonia Rating Scale 62 is preferred for routine use, because of its validity, reliability and ease of administration. For dyskinesia and parkinsonism, the most commonly used instruments are the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale 63 and the Simpson‐Angus Scale 64 , respectively. The St. Hans Rating Scale for Extrapyramidal Syndromes 65 rates comprehensively all EPS, including dyskinesia, parkinsonism, akathisia and dystonia.

Acute and severe catatonia is best managed using electroconvulsive therapy, although less severe catatonia symptoms may respond to benzodiazepines or second‐generation antipsychotics. Established drug‐induced EPS should be managed by reducing or changing antipsychotic medication, particularly in subjects treated with first‐generation antipsychotics. In this regard, clozapine and quetiapine are among the second‐generation antipsychotics with the lowest risk of producing neurological side effects 66 .

Major mood symptoms are found in about 30% of cases of primary psychosis during an index episode, and their prevalence rate reaches 70% when lifetime mood ratings are considered 67 .

A frequent diagnostic problem during an acute episode is the differentiation between mood disorders with psychotic features and primary psychosis 68 . In this regard, examining the temporal pattern of the association between psychotic and mood syndromes, and using specific mood rating scales that do not include psychotic symptoms, are highly desirable. The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia 69 is the best option for assessing depression in the context of psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, a similar instrument does not exist for mania, since all available mania rating scales also include psychotic symptoms to some degree. The mania subscale from the CASH 58 may be reliably used. The relevance of mood symptoms for the management plan in primary psychosis is discussed elsewhere in this paper.

Lack of insight is a hallmark feature of primary psychosis, entailing three relatively overlapping subcomponents: awareness of symptoms, awareness of illness, and collaboration with treatment. Poor insight is strongly related to reality distortion and disorganization symptoms; in contrast, higher cognitive ability and depressive symptoms are associated with better insight. Poor insight has important clinical and management implications, since it is associated with a number of interrelated factors, including longer duration of untreated psychosis, poor collaboration with treatment, and aggressiveness, all of which result in poor outcomes 70 .

The standard instrument for assessing clinical insight is the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder 71 . This scale, however, may be too time‐consuming for use in routine clinical practice. An alternative option is to use the three AMDP 59 items covering the insight domains referred to above.

Recently, a distinction has been made between clinical insight and cognitive insight, the latter describing the subject’s flexibility towards his/her beliefs, judgments and experiences. The self‐report Beck Cognitive Insight Scale 72 examines two subcomponents of cognitive insight: self‐certainty (i.e., overconfidence in the validity of one's beliefs) and self‐reflectiveness (i.e., capacity and willingness to observe one's mental productions and to consider alternative explanations). These two distinct but related aspects of cognitive insight in psychosis appear to be differentially associated with clinical insight, symptoms and functioning.

During an acute episode, improvement of insight co‐varies with improvement of psychotic symptoms. However, in a substantial proportion of subjects with chronic schizophrenia, lack of insight may represent a major therapeutic challenge. Insight‐focused CBT is often recommended, although research findings are conflicting about its efficacy. Metacognitive reflection and insight therapy (MERIT), an individual psychotherapy seeking to enhance the reflective capacity necessary for people who have experienced severe mental illness to form a complex and integrated sense of self and others, has been proposed as an alternative 70 .

Depressive symptoms and the presence of insight are associated with a higher risk for suicide in patients with primary psychosis. Being young, male and with a high level of education, prior suicide attempts, active hallucinations and delusions, a family history of suicide, and comorbid substance abuse are also positively associated with later suicide, while the only consistent protective factor is delivery of and adherence to effective treatment 73 . The Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale 74 is a validated tool for the assessment of suicide risk, whose administration requires a specific training that is available online.

Sleep disturbances, in particular insomnia, are common in persons with primary psychosis 75 , and can have a significant impact on their quality of life 76 . Their presence should be explored in the clinical characterization of the individual patient, because they can be targeted in CBT and considered in the choice of the antipsychotic medication. Furthermore, obstructive sleep apnea has been reported to be more frequent in these patients than in the general population, and can be related to the dosage of the antipsychotic medication 77 .

ONSET AND COURSE

The onset of primary psychosis usually occurs in adolescence or early adulthood 78 . On average, men are diagnosed in their late teens to early twenties, whilst women tend to get diagnosed in their late twenties to early thirties.

Onset of primary psychosis should be distinguished from the expression of premorbid developmental alterations in the domains of cognition, motor function and social adjustment. Follow‐back studies indicate that the first changes often involve affective and negative symptoms, appearing years before diagnosis. Positive symptoms emerge later and typically trigger contact with mental health services. Indicators of social disability appear 2‐4 years before onset. Cannabis use is associated with an earlier onset of psychosis.

Onset can be considered as a three‐stage process, consisting of: a) a prodrome, in which a period of non‐specific “unease” precedes “non‐diagnostic” symptoms in the form of disturbances of perceptions, beliefs, cognition, affect and behavior; b) first expression of psychotic symptoms; and c) increase in characteristic symptoms resulting in a definite diagnosis. The prodrome can be absent or not identifiable in several patients.

The Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS) is a short guided interview and rating schedule to assess onset in psychosis, defined as the time between the first changes in mental state and behavior to the appearance of psychotic symptoms 79 . Other instruments providing comparable onset assessment are the CASH 58 and the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory 80 .

The International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia 81 categorized mode of onset into three groups: a) acute (psychotic symptoms appear within hours, one week or one month since first noticeable behavioral change); b) gradual (psychotic symptoms appear within one to six months since first noticeable behavioral change); and c) insidious (psychotic symptoms appear incrementally over a period of six months or greater since first noticeable behavioral change). There is some evidence that the insidious mode of onset is associated with poorer and the acute onset with better outcome.

The course of primary psychosis after onset is highly variable both within and between patients. There is a broad range of possible course patterns, ranging from complete recovery to continuous unremitting psychopathology, cognitive alterations and social disability. Between such extremes, a substantial number of patients present with multiple episodes of psychosis interspersed with partial remission 82 . On average, within the primary psychosis syndrome, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have the poorest outcome, with schizoaffective patients occupying an intermediate position between schizophrenia and affective psychosis 83 . Patients diagnosed using a broad definition of schizophrenia generally have better outcomes than those diagnosed with narrowly defined (post‐DSM‐III) schizophrenia.

The Life Chart Schedule 84 was designed to assess the course of psychotic disorder in four key domains (symptoms, treatment, residence and work) over several time periods. Course type can be rated as episodic (no episode longer than six months), continuous (no remission longer than six months), neither episodic nor continuous, and not psychotic in this period. Type of remission can be coded as “mainly complete”, “mainly incomplete” and “mixed”. A “usual severity of symptoms” rating is made to indicate the symptomatic level of the patient during most of the period under observation. Ratings are “severe”, “moderate”, “mild” and “recovered”. The amount of time spent in a psychotic state is also rated, as are parasuicidal acts and instances of assault. A rating is also given as to whether there was clear evidence of negative symptoms over the period under observation. In addition, the life chart rates the proportion of the period spent unemployed (time in institutions not counted; full‐time students and housewives rated as employed), living independently, in hospital, in prison, or without accommodation. In addition, treatment variables over time (hospitalization, use of antipsychotic medication, other interventions) are recorded.

In a given patient with a given length of illness, the assessment of preceding course is essential, because it allows for the formation of hypotheses about the effectiveness of treatment across different outcome domains to date. The first five years of the illness are considered “critical”, referring to the hypothesis that early energetic treatment may causally impact on the later course of the syndrome. After the first episode, around 90% of patients will experience a remission of symptoms. After five years, however, 80% will have experienced one or more relapses. With each episode, a small proportion of patients will develop a continuous illness course, displaying a mix of persistent positive and negative symptoms, cognitive difficulties and catatonia. Over the course of five years, around 40% of patients with primary psychosis can be expected to show “good” outcome (with 15% showing complete recovery), 20% “poor” outcome, and 40% “intermediate” outcome 85 . Thus, assessment of course to date is necessary to place the patient at the right position on dimensions of illness episodicity and inter‐episode recoverability, thus informing continued clinical management.

After the first ten years after onset, the illness course tends to plateau. Cross‐sectional outcome measures of psychopathology do not differ substantially according to study duration, suggesting that there is no clear pattern of deterioration or “progression”, although this may occur in a subgroup of patients. Careful assessment of course over time in a patient with long duration of illness can reveal signs of progression and possible reasons thereof.

Course and outcome cannot be defined unidimensionally. For patients, the most important outcome, apart from societal participation (education, work, housing, relationships), is restoration of perspective, in the sense of feeling that life is meaningful and worth living (existential recovery) 86 . The Recovery Assessment Scale can be used to evaluate the course of existential recovery over the period preceding the assessment 87 . This evaluation is essential, as it provides information on the causes of variation and the possible role of the health system herein, including unintended iatrogenic hopelessness, antipsychotic polypharmacy, and post‐traumatic stress after admission. These may be counteracted by facilitating peer‐supported interventions focusing on hope, connectedness, identity, meaning and empowerment.

Over time, patients (and their environment) learn about their mental vulnerability, the relativity of formal diagnosis, the limitations of treatment, the gaps in knowledge, and the weak spots in local service provision. As a result, they become more involved in and opinionated about treatment and services 88 , so that the process of shared decision‐making becomes even more essential. It is therefore important to assess, before planning the clinical management, the preceding course of decision‐making about diagnosis and treatment, and the experience to date in being able to experiment with dosing and even discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment, to engage in alternative therapies and in general to take risks in pursuit of life goals.

In order to be able to deal with an intense mental vulnerability, characterized by an often unpredictable waxing and waning expression over time, a long‐term therapeutic relationship of trust and mutual commitment is essential. Assessment of course, therefore, should include the quality and level of therapeutic continuity over time, and its impact on outcome to date.

NEUROCOGNITION

Neurocognitive alterations have been identified as a key component of schizophrenia since the clinical observations of Bleuler and Kraepelin, but they have gained much more clinical and research attention in recent years3, 89. These alterations are present in many cases years before the first psychotic episode 90 , persist into clinical remission 91 , and may be present in a milder form in first‐degree relatives of patients 92 .

As the role of neurocognitive alterations in predicting and influencing everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia became more widely recognized 93 , the US National Institute of Mental Health promoted the development of a consensus on the major dimensions of this neurocognitive impairment, their measurement in clinical trials, and the design of trials to evaluate potential treatments 94 . This initiative, Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS), led to the identification of seven major dimensions: speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and problem solving, and verbal comprehension 95 .

Speed of processing refers to the speed with which simple perceptual and motor tasks can be performed, which is believed to reflect the pace of cognitive processing. Attention/vigilance refers to sustaining a focus on relevant information over a prolonged period of time. Working memory involves temporary maintenance and manipulation of information in consciousness, usually over a few seconds. Verbal learning and memory refers to the initial encoding and later recognition and recall of words and other information involving language. Visual learning and memory involves similar encoding, recognition and recall processes for visuospatial information such as shape, color, spatial orientation, and movement.

Reasoning and problem solving refers to processes of strategic and logical thinking, planning, formation and maintenance of goals, and coordinating these processes flexibly over time. Reasoning and problem‐solving abilities are sometimes also called executive processes. Finally, verbal comprehension refers to verbal information that is accumulated over many years and stored in a widely distributed neural network, such as vocabulary and common shared information in a culture.

While all of these dimensions are impaired in schizophrenia, the MATRICS Neurocognition Committee concluded that verbal comprehension is not likely to be impacted to a notable degree by pharmacological or psychosocial interventions and is therefore less relevant as a focus for clinical trial or clinical practice assessment.

The typical person with a post‐DSM‐III diagnosis of schizophrenia scores between 0.75 and 2.00 standard deviations below community samples of similar age and gender on each of these neurocognitive domains 96 , which corresponds to a percentile between 2% and 24%. Thus, the cognitive alterations, on average, are large and generalized across cognitive domains, with perhaps larger alterations in speed of processing than in other domains 97 . While the overall picture is one of a generalized impairment across neurocognitive domains, there is also notable heterogeneity in the profile of alterations from one patient to the next, which may to some extent also be due to a different impact of interfering factors such as disturbances in motivation and emotion3, 98. The variability in neurocognitive performance is likely to be even higher in patients fulfilling the broader ICD‐10/ICD‐11 definition of schizophrenia and in those with ICD‐10/ICD‐11 “other primary psychotic disorder”, although no research evidence is available in this respect. The clinical importance of these domains of neurocognitive impairment is very clear, as each one is significantly related to the level of work/school and social recovery that a patient is able to achieve99, 100.

In clinical practice, the options for assessing neurocognitive alterations fall into three categories: comprehensive cognitive performance assessment, brief cognitive performance assessment, and interview‐based measures of cognition.

Comprehensive cognitive performance assessment batteries allow the clinician to identify the individual profile across the six neurocognitive domains, and to plan tailored interventions and clinical management accordingly. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) was developed through a systematic expert consensus process, and measures each of the domains with tests that are reliable, repeatable and sensitive to change 101 . It requires about 65 min to administer and yields standardized scores for each cognitive domain and for a neurocognitive composite across domains 102 . Other well‐developed comprehensive batteries include the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) 103 and the CogState 104 , both of which consist of reliable, repeatable measures of most or all MATRICS neurocognitive domains.

The disadvantages of these comprehensive batteries for clinical practice are that they are relatively lengthy and require adequate professional training for administration and interpretation. An alternative would be to complete one of these batteries at initial assessment and then choose one to three of their tests for tracking change based on the initial profile of neurocognitive alterations.

Brief cognitive performance assessments have the advantage of being less time‐consuming, while still allowing changes in at least overall cognitive performance to be evaluated over time. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) 105 involves six tests and 35 min for administration, while the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) 106 covers five cognitive domains in about 30 min. Both yield reliable and valid measures of global cognitive functioning that correlate well with overall scores from comprehensive batteries, as well as some information about the pattern of alterations.

Even shorter cognitive screening measures include the 15‐min Brief Cognitive Assessment 107 and the 10‐min Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool for Schizophrenia (B‐CATS) 108 . Both of these brief tools yield a global cognitive score that correlates well with comprehensive battery composite scores, but they do not allow any pattern of alterations to be evaluated. All of these measures still require professional training, but less than the comprehensive batteries.

Finally, interview‐based measures of cognition are intuitively attractive for ordinary practice, as clinicians are accustomed to interview formats and can more easily adapt to their administration. The Cognitive Assessment Interview (CAI) 109 requires 15 min to administer, and has high test‐retest reliability and moderate relationships to performance‐based cognitive measures and everyday functioning. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS) 110 also takes about 15 min per interview, has good test‐retest reliability, and moderate relationships with cognitive performance measures and everyday functioning. The SCoRS yields stronger relationships when an informant is used rather than solely a patient interview.

Both these interview‐based measures of cognition require some training. While both yield an overall cognitive score, the relationship of these scores to cognitive performance measures is weaker than the interrelationship of cognitive performance measures to each other. They also do not provide a reliable pattern of alterations across cognitive domains.

Given the clear influence of neurocognitive alterations on everyday functioning in primary psychosis, the importance of treatment plans that address these alterations is increasingly recognized. Although attempts to develop cognition‐enhancing adjunctive medications have promise for the future, so far cognitive remediation 111 , aerobic exercise 112 , and perhaps their combination 113 are most relevant for clinical practice.

Aerobic exercise has thus far been shown to improve overall neurocognition and specifically attention/vigilance and working memory 112 . Cognitive remediation produces moderate gains in overall cognition and several cognitive domains, with larger neurocognitive and everyday functioning improvements being achieved when it is implemented in the context of active rehabilitation programs 111 . Emerging evidence indicates that forms of cognitive remediation that emphasize perceptual processes vs. higher‐level executive processes impact on different neurophysiological mechanisms 114 . Furthermore, perceptual training may be beneficial only for patients with initial perceptual processing impairments 115 .

Thus, beyond assessment of the level of overall cognitive impairment, identifying neurocognitive domains with particularly severe alterations is becoming of increasing importance in the clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis.

SOCIAL COGNITION

Social cognition refers to mental operations needed to perceive, interpret and process information for adaptive social interactions. The term encompasses a very broad range of domains. In the context of primary psychosis, most of the attention has focused on four aspects of social cognition: emotion identification, mentalizing, social perception, and attributional bias3, 116.

Emotion identification includes one’s ability to perceive emotion in faces, voice intonation, gestures or gait. Mentalizing refers to the ability to infer intentions or beliefs of others, such as whether they are being sincere, sarcastic or deceptive. Social perception refers to the ability to identify social roles, social rules and social contexts from various cues. Individuals with a post‐DSM‐III diagnosis of schizophrenia have alterations on all three of these aspects of social cognition based on performance‐based measures 117 , although this notion may not be generalizable to all patients fulfilling the broader ICD‐11 definition of schizophrenia or to those with ICD‐11 “other primary psychotic disorder”.

Attributional bias refers to how individuals typically infer the causes of particular positive and negative events (e.g., having a tendency to attribute hostile intentions to others). Unlike the other social cognitive areas, people with schizophrenia do not consistently show differences in attributional bias compared with healthy individuals117, 118.

Social cognition is relevant to the management of primary psychosis because it is associated with functional outcome 100 . Consistent associations between social cognitive domains and community functioning have been reported in schizophrenia, with mentalizing showing the strongest relationship in one meta‐analysis 100 . Further, social cognition explained more variance in community functioning than did nonsocial cognition (16% vs. 6%). Thus, social cognition is a key correlate and determinant of functional outcome in primary psychosis, and can help clinicians to form realistic expectations for how the individual patient might integrate in the community, or how much additional support he/she may need to do so.

Given its relevance for functional outcome, there have been considerable efforts, and some encouraging progress, in developing psychosocial training interventions for social cognition in primary psychosis. These interventions are typically interactive and group‐based, and include a variety of visual, auditory and video stimuli depicting social stimuli. Recently, individual computerized interventions have also been developed 119 . One meta‐analysis of 16 studies 120 found improvements of large effect sizes in facial affect identification (d=.84), mentalizing (d=.70), and social perception (d=1.29). The impact of these interventions on functional outcome has been encouraging, though not consistent across studies 121 .

Beyond psychosocial training interventions, there are considerable efforts to examine the impact of intranasal oxytocin (using single or repeated administration strategies) on social cognitive tasks. Here, however, the results in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have been mixed, with both positive and negative findings 122 . Another approach has been to examine oxytocin as an augmentation during social cognitive training programs, and again the results have been mixed 123 .

Measurement of social cognition in primary psychosis has been a daunting challenge. The measurement problems apply to both clinical trials and ordinary practice. Regarding clinical trials, there is no consensus on a battery of social cognition outcome measures, or even a set of social cognitive domains. A highly diverse range of outcome measures have been used in treatment studies, and they often have poor or unknown psychometric properties.

Considering the lack of psychometric information on potential social cognitive endpoints for clinical trials of psychosis, the US National Institute of Mental Health supported two method‐development projects. One project focused on evaluation of social cognitive measures that were in current use in psychopathology 124 , while the other adapted measures from social neuroscience and evaluated their application to people with psychosis 125 . Both projects produced a rich data set and a series of recommendations for endpoints in clinical trials. Despite these efforts, there is no widely‐used battery for measurement of social cognition in clinical trials.

The absence of such standardization means that results from trials vary depending on the specific outcome measure 126 . For example, the majority of studies that found treatment effects for mentalizing used very simple tasks or questionnaires. However, a more challenging and ecologically valid test is The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT) 127 , which has good psychometric properties. This test uses video vignettes, and participants are asked to detect lies and sarcasm. Studies using this test have generally failed to find treatment effects. A similar pattern was seen for the domain of social perception. If more challenging and psychometrically stronger measures tend to show smaller or negative findings, this raises questions about the strength of treatment effects for certain domains.

In contrast, other aspects of social cognition, such as facial affect perception, show treatment effects regardless of the specific outcome measure. Attributional bias presents a different measurement issue: there are very few available measures for this domain, and the current ones do not have strong psychometric properties 124 .

The situation for the assessment of social cognition in clinical practice is similarly problematic. In contrast to nonsocial cognition, social cognition does not have a long history of clinical evaluation with standardized and highly reliable measures. Partly due to this historical lack of emphasis, it is rarely evaluated in routine cognitive or neuropsychological assessments.

This situation is going to change. Some innovative and interpretable tests of emotion processing are emerging, including an emotion processing battery with a large normative sample, the Mayer‐Salovey‐Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) 128 . Also, some social cognitive domains lend themselves to brief assessments that do not require expertise in test administration. For example, there are a large number of tests for facial or vocal emotion perception that are easy to administer and do not depend on language (i.e., could be used cross‐nationally) 129 .

Nonetheless, at the current time, measurement remains the Achilles’ heel of social cognition. Social cognition is an important and functionally meaningful aspect in primary psychosis, but it has not yet moved into broad clinical application.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL INDICATORS

The neurodevelopmental understanding of primary psychosis has evolved along the decades, from Kraepelin’s remarks 130 on the developmental differences in children who as adults would manifest dementia praecox; to the contributions of Fish 131 , who recognized a continuity between infant development and risk of early psychosis; Weinberger 132 , who postulated an early genetic or environmental insult to the developing brain interacting with normal adolescent development; and Murray and Lewis 133 , who proposed a subtype of schizophrenia being a long‐term sequela of obstetric injury.

Subsequently, evidence has accrued with epidemiological research using prospective information, particularly from birth cohorts and population registers, to support wide‐ranging manifestations of neurodevelopmental effects in primary psychosis. Indeed, the incidence of primary psychosis peaks between puberty and the mid‐twenties, an epoch of renewed grey and white matter changes and a sensitive period for psychosocial development.

Earlier neurodevelopmental indicators in primary psychosis are highly relevant to clinical practice. They include a history of delayed or reduced acquisition of early childhood motor and language skills, atypical age‐appropriate social interaction, and lower IQ and school attainment throughout childhood and adolescence134, 135, 136, 137. Furthermore, soft neurological signs have a prevalence of 50‐65% in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (compared with 5% in healthy controls) 138 . All these elements offer a window on neurodevelopment, as well as informing clinical management and prognosis.

Soft neurological signs include dysgraphaesthesia (the inability to recognize writing on the skin through touch alone), diminished motor coordination, and problems with complex motor sequencing (such as dysdiadochokinaesia, an impairment in rapid alternating movements). They also encompass persistence of infantile (primitive) reflexes such as the palmomental response (reflex contraction of the mentalis muscle leading to pouting of the lower lip when the palm is scratched), increased blink rate, and a positive glabellar tap (no habituation of blinking when the glabella is tapped).

Soft neurological signs are readily understandable in terms of distributed or circuit dysfunction rather than a localized lesion. They are present from early in development and most likely share the same underlying network‐based mechanisms as the pandysmaturation reported in genetically high‐risk children 139 and the early motor and language milestone delays seen more broadly in primary psychosis.

Minor physical anomalies (i.e., dysmorphic features representing subtle alterations in the development of somatic structures) have also been observed in some patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, with high‐arched palate being particularly common (20‐25% of patients) 140 .

Consideration of neurodevelopmental indicators is important in the clinical assessment of a patient with primary psychosis. Their presence helps to confirm the diagnosis where other phenomenology is scant (e.g., presentations with catatonia or mutism) or where a secondary psychosis is a realistic differential. They can be seen as direct precursors of negative symptoms such as alogia, affective blunting and asociality, and of cognitive alterations. These aspects are challenging to manage clinically, and presage poorer outcome.

The identification of neurodevelopmental markers may support a causal formulation in an individual patient, particularly where there has been obvious obstetric mishap or early trauma such as pre‐ or neonatal infection. They also illuminate an individual patient’s psychosocial life history whereby developmental differences from childhood peers is likely to have created an altered social microenvironment during development and a cascade of abnormal experiences 134 , something that needs accommodation in a management plan aiming at functional recovery.

It is also important to assess whether neurodevelopmental indicators are present to such an extent that an alternative diagnosis is more appropriate, such as psychotic phenomena in the context of an autistic spectrum disorder or a learning disability syndrome, particularly where the psychosis itself is similar to a primary syndrome 141 but is treatment resistant 142 . These classical neurodevelopmental disorders may remain undiagnosed into early adulthood and present atypically.

Further investigations, including evaluation by a clinical geneticist, may be required where there are multiple minor physical anomalies or when, collectively, they suggest a specific genetic condition such as velocardiofacial syndrome. Even where the observed picture does not meet diagnostic criteria for a neurodevelopmental disorder, advice from clinicians experienced in these fields can be useful, given the transdiagnostic occurrence of psychotic and neurodevelopmental features 143 .

The evaluation of soft neurological signs should be part of the full neurological examination required in every patient with primary psychosis 144 , but there are scales intended for both clinical and research practice that can be helpful. The Cambridge Neurological Inventory 145 was developed for the full range of psychiatric conditions and is applicable to primary psychosis. In this inventory, the second part focuses on soft sign examination (primitive reflexes, repetitive sequential motor execution, and sensory integration). The longer Neurological Evaluation Scale 146 focuses on schizophrenia. It includes 26 items, clustered into three subscales (sensory integration, motor coordination, and sequencing of complex motor acts).

The systematic assessment of childhood neurodevelopmental indicators presents a particular challenge in primary psychosis. Effects seen in research using prospective data may be subtle (standing, walking or speech delayed by four to six weeks) and would have been barely noticeable at the time, given the wide range of normal experience, or may simply have been forgotten, even by parents. Contemporary health or school records may be sought, if available. Despite these caveats, inquiry into the developmental history is important.

The Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)147, 148 evaluates the level of functioning in four major areas (social accessibility ‐ isolation, peer relationships, ability to function outside the nuclear family, and capacity to form intimate socio‐sexual ties) at each of four periods of the subject’s life: childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12‐15 years), late adolescence (16‐18 years), and adulthood (19 years and beyond). The final section contains items estimating the highest level of functioning that the subject achieved before becoming ill. The scale is intended to measure only “premorbid” functioning, and its questions have been updated to discount the entire year before the first psychiatric contact, in order to accommodate contemporary focus on early detection and intervention 148 . Ratings are based on reports from family members or clinical records. When it is felt that the patient is reliable, a personal interview may be conducted to complete the ratings. The scoring for each item ranges from “0”, corresponding to the healthiest end of the adjustment range, to “6”, corresponding to the least healthy end. Asking informants to compare and contrast with the patient's siblings is often helpful.

Overall, consideration of neurodevelopmental indicators can be useful to obtain a more complete characterization of the patient with primary psychosis, help in differential diagnosis, and contribute to the formulation of a more comprehensive and targeted management plan.

SOCIAL FUNCTIONING, QUALITY OF LIFE AND UNMET NEEDS

Impairments of social functioning in schizophrenia have been described since the time of Kraepelin 130 . Social functioning is a broad term, which includes milestones such as marriage or equivalent relationships, social interactions such as friendships, as well as social skills and social motivation. Further, social functioning is related to quality of life, the definition and assessment of which have been complex and occasionally obscured in research on primary psychosis.

Impairments of social functioning in patients with a post‐DSM‐III diagnosis of schizophrenia have several features. People with this disorder are much less likely than the general population to experience marriage or equivalent milestones 149 . They also have smaller social networks, and are likely to nominate a clinician as the person who knows them best 110 . The generalizability of these findings to all patients fulfilling the broader ICD‐11 definition of schizophrenia or to those with ICD‐11 “other primary psychotic disorder” remains uncertain.

Social anhedonia is the phenomenon whereby people with schizophrenia experience less pleasure from social interactions and manifest reduced interest in these interactions. In fact, many of them rarely leave their homes, being home as much as 70% or more of the time 150 . It is a complex phenomenon, because there is evidence that individuals with schizophrenia enjoy social activities as much as healthy individuals at the time of the experience, but have challenges in recalling this enjoyment in order to motivate later interactions 151 .

Another feature of social functioning in schizophrenia is an impairment in social skills or social competence. Many people with this disorder have reduced ability to interact with others and may make socially inappropriate statements or gestures 152 . These problems make interactions challenging and may reduce the willingness of others to engage with them.

In addition to data on current social functioning, the assessment needs to consider motivation to engage in social activities, the level of social competence, and the individuals’ evaluation of their ability compared to objective information (social milestones). Understanding the level of social motivation will be critical for the development of treatment strategies, as social skills training will not improve social outcomes in people who have no plans to engage in social activities 153 , and targeted treatment aimed at negative symptoms associated with poor social outcomes is now proven effective 154 .

Several social functioning scales are available, and most are very easy to use in practice. The Specific Levels of Functioning (SLOF) has been found to be the rating scale wherein informant reports are most consistently correlated with objective data from performance‐based assessments 155 . This 31‐item scale has three subscales (vocational, social, and everyday activities). It is easily completed and requires no special training.

The Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) 156 also collects data on social and everyday activities. Also amenable to informant report, this scale generates both domain and total scores. The domains are socially useful activities (including work and school), personal and social relationships, self‐care, and disturbing and aggressive behavior. Impairments in the four domains are rated on a 6‐point scale (from “absent” to “very severe”), with a global score ranging from 0 to 100. As functional impairments in primary psychosis are relatively uncorrelated across domains, consideration of domain scores instead of a total score is highly recommended.

For the critical assessment of motivation to engage in social activities, there are several possibilities. Self‐reported measures include the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS) 157 , which captures the level of enjoyment in pleasurable activities (consummatory pleasure) and the anticipation of pleasure in these activities (anticipatory pleasure). A similar assessment of sensitivity to pleasurable activities is the Motivation and Pleasure Scale ‐ Self‐Report (MAP‐SR) 158 . This scale is designed to be a self‐report measure that parallels the widely used negative symptoms assessment by the CAINS 54 . All of these scales capture subjective motivation, which has been found to correlate quite strongly with actual social outcomes measured by an independent rater, by‐passing the need for a structured interview procedure.

Problems in social competence are usually treated with social skills training, while recent treatments aimed at motivational impairment have used technology‐based interventions such as the Personalized Real‐time Intervention for Motivational Enhancement (PRIME) 159 . This is a mobile application which first assesses the participant’s level of engagement with others and in activities and then uses those assessment data to make suggestions regarding possible activities to engage in: “Why don't you try to visit someone in your family today?”. Cognitive behavioral interventions have shown efficacy for improvement of social skills and concurrent reduction of socially relevant negative symptoms 154 .

Quality of life in primary psychosis is multi‐faceted and only partially overlapping with social functioning. Objective quality of life indicators include the milestones noted above, as well as employment, independence in living, and other elements of maintenance of normal adult autonomy. Subjective quality of life is the report of both activities performed and the individuals’ subjective response to these activities. It has been widely confirmed that overlap between objective and subjective quality of life indices is reduced in people with schizophrenia, with evidence of under‐estimation of level of impairment found objectively160, 161.

In terms of subjective quality of life, several scales are readily available. It is important to capture patient quality of life reports, even if divergent from objective information, because patients’ motivation to engage in multiple different treatments will be based on their perception of their current level of functioning.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale (WHO‐QOL) 162 has been widely used to assess subjective quality of life. This scale has the benefit of being self‐administered. It examines quality of life in the domains of physical and mental health, social relationships, and the environment.

A rater‐administered scale, the Quality of Well‐Being scale (QWB) 163 , captures subjective illness burden and has the advantage of providing norms across different illnesses, including psychiatric and physical conditions. This is a more challenging assessment which requires training to administer.

A main driver of quality of life in persons with primary psychosis is represented by the dimension of unmet needs 164 . Unmet needs are frequently found in the areas of daytime activities, information, company, intimate relationships and sexual expression. In many parts of the world, housing, employment and social benefits also represent frequent unmet needs in people with primary psychosis 165 .

Including these elements in the clinical assessment framework is important for several reasons. First, a perspective of needs is humanizing and normalizing. There is, in fact, a widely recognized universal hierarchy of human needs as defined by Maslow 166 : physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self‐actualization needs. Second, the concept of need recognizes the service user’s experience and preference, given that assessment requires his/her perspective on what is “unmet”.

Assessment of needs thus becomes an active process of exploration, listening and understanding on the part of the clinician, often requiring a degree of negotiation between clinician and patient, which in turn will enhance the likelihood of shared decision‐making. This is important, as better staff‐patient agreement on needs makes a significant additional contribution in predicting treatment outcomes 167 , and staff with an active and shared decision‐making style has more impact on reducing unmet needs over time 168 .

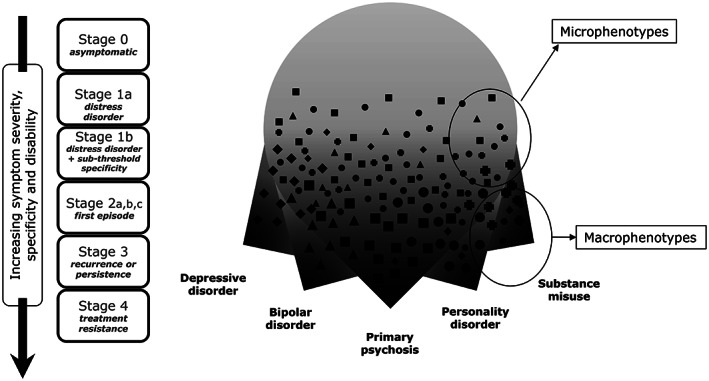

Third, the assessment of needs automatically takes into account the level of contextual influences, such as the impact of friends, family and informal help, in making a need met or unmet. This enhances the sensitivity of the mental health service to the role of informal carers and other resources in the network. Finally, there is evidence that systematic monitoring of patient needs may result in better outcomes and is cost‐effective169, 170, 171.