Subgroup analyses assess whether a given effect measure differs according to baseline characteristics [1]. In general, treatment effects can be measured on a relative (i.e., odds ratio or risk ratio) or absolute (i.e., risk difference) scale when an outcome is binary. If a treatment has an effect and the control-group outcome differs according to the subgroup characteristic, conclusions about subgroup differences will depend on the scale of the effect measure used.

To evaluate the reporting of subgroup analyses in the NEJM, a review of the last 100 randomized trials reporting subgroup analyses was performed (see Supplemental Appendix for methodological details). Twenty-eight trials reported a binary primary outcome. The primary results were reported as an odds ratio in four trials (14%), risk ratio in 13 trials (47%), and a risk difference in 11 trials (39%). Five trials (18%) reported two effects measures. There was substantial heterogeneity in the effect measure used for subgroup analyses: 17 trials (61%) assessed subgroup differences on a relative scale, nine trials (32%) assessed subgroup differences on an absolute scale, one trial (4%) reported both scales, and one trial (4%) did not report the scale.

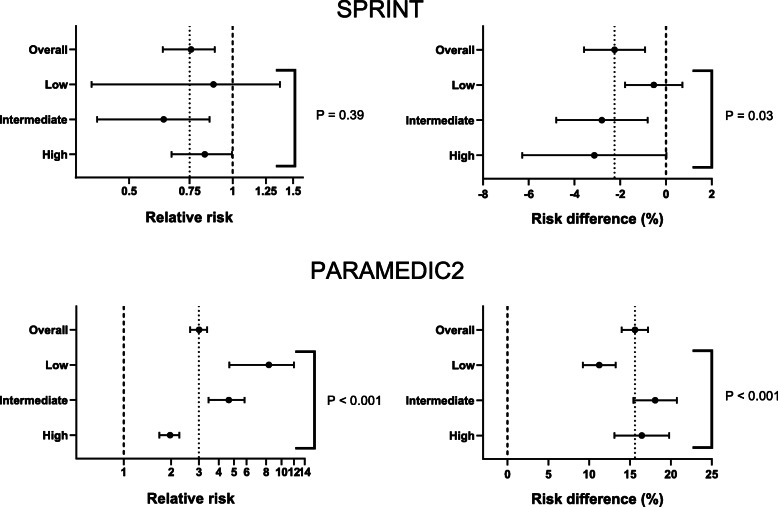

To illustrate how the scale can have importance for interpretation of results, subgroup analyses according to estimated baseline risk (low, intermediate, high) were performed using data from SPRINT [2] and PARAMEDIC2 [3] (see Supplemental Appendix for methodological details). Relatively constant risk ratios across baseline risks in SPRINT translated to more variability in risk differences (Fig. 1, Table S1). By contrast, substantial differences in risk ratios across baseline risk in PARAMEDIC2 translated to more constant (although still different) risk differences (Fig. 1, Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Subgroup analyses based on estimated baseline risk. The outcome of interest was the primary outcome from SPRINT (a composite of cardiovascular outcomes) and survival to hospital admission for PARAMEDIC2. Patients were divided into three groups based on their baseline risk of the outcome (low, intermediate, high). Subgroup analyses were then performed within these categories on the relative scale (left) and the absolute scale (right). The thin dashed vertical line represents the effect in the overall cohort. The thick dashed vertical line represents no effect. The P value is from the subgroup and intervention interaction. Additional details are provided in the Supplemental Appendix

Meta-epidemiological studies suggest that relative effects are generally more constant across baseline risk as compared to absolute effects [4–6]. Some authors therefore argue that subgroup analyses on the relative scale are of most interest [7]. However, as demonstrated here, subgroup analyses do not consistently abide by this rule. Despite recommendations to present absolute risk differences in addition to relative measures when reporting clinical trials [8], the findings of this study suggest it is not common practice for subgroup analyses. As relative and absolute risks are often interpreted differently, the choice of scale could have implications for behavior and treatment choices. Absolute risk differences are particularly relevant for decision making and public health, as effect measure modification on the absolute scale is believed to represent actual biological interaction between the subgroup characteristic and the intervention [9]. Given the implications for interpretation, authors should consider reporting subgroup analyses on both the absolute and the relative scale or, as a minimum, justify the scale used.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for sharing SPRINT data and Gavin Perkins, M.D. and the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Warwick for sharing PARAMEDIC2 data. I would also like to thank Lisa Caulley, M.D., M.P.H., who provided valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Author’s contributions

LWA conceived and designed the study, acquired the data, did the statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

Data from SPRINT can be requested through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Data from PARAMEDIC2 can be requested from Gavin Perkins, M.D. and the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Warwick. Data obtained through the review of trials can be requested from the author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine--reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2189–2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprint Research Group. Wright JT, Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of Intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, et al. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(8):711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid CH, Lau J, McIntosh MW, Cappelleri JC. An empirical study of the effect of the control rate as a predictor of treatment efficacy in meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998;17:1923–1942. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980915)17:17<1923::AID-SIM874>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa TA, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE. Can we individualize the ‘number needed to treat’? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:72–76. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med. 2002;21:1575–1600. doi: 10.1002/sim.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X, Ioannidis JP, Agoritsas T, Alba AC, Guyatt G. How to use a subgroup analysis: users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA. 2014;311:405–411. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman J, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from SPRINT can be requested through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Data from PARAMEDIC2 can be requested from Gavin Perkins, M.D. and the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Warwick. Data obtained through the review of trials can be requested from the author.