Abstract

Here we present the case of a 37-year-old previously healthy man who developed fever, headache and a unilateral, painful neck swelling while working offshore. He had no known contact with anyone with COVID-19; however, due to the ongoing pandemic, a nasopharyngeal swab was performed, which was positive for the virus. After transfer to hospital for assessment his condition rapidly deteriorated, requiring admission to intensive care for COVID-19 myocarditis. One week after discharge he re-presented with unilateral facial nerve palsy. Our case highlights an atypical presentation of COVID-19 and the multifaceted clinical course of this still poorly understood disease.

Keywords: cardiovascular medicine, infectious diseases, neurology

Background

In the early stages of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, COVID-19 was characterised primarily as a respiratory disease with complications including acute respiratory distress syndrome. It is now clear that COVID-19 can affect multiple organ systems with a wide range of short-term, medium-term and long-term complications.1 2 COVID-19 myocarditis is an important though still poorly understood phenomenon.3 Case reports have documented that younger, previously healthy patients can develop significant cardiac injury even with milder disease presentations.4 5 Prompt detection, isolation and management of the virus in order to minimise transmission and reduce complications rely on recognising the spectrum of clinical presentations, including cardiac and neurological manifestations.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 37-year-old man developed fever, headache and a unilateral, painful neck swelling while working on an offshore platform. He had no significant medical history, no recent international travel and no known contact with anyone with COVID-19. Despite his presenting symptoms giving little indication of COVID-19 infection, for training purposes in the early phase of the pandemic he was transported in an EpiShuttle (single-patient isolation transport system) when he was evacuated to hospital for assessment.

On admission he had an area of redness in the posterior palate and a tender, non-fluctuant swelling extending from the left mandibular angle towards the sternocleidomastoid muscle. He denied any cough, neck stiffness, pain on swallowing, respiratory distress or chest pain.

He was febrile at 41°C, tachycardic at 115 beats per minute, normotensive at 119/76 mm Hg and mentally alert. He had an intermittently raised respiratory rate varying between 12 and 22 breaths per minute and a peripheral oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Systemic examination, including auscultation of the heart and lungs, was unremarkable.

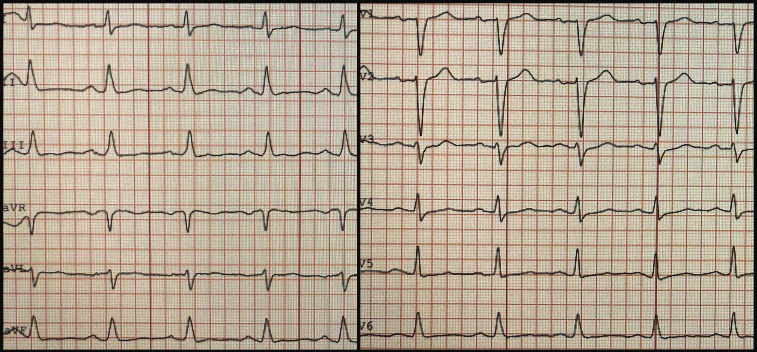

A routine ECG showed sinus tachycardia with moderately flattened T-waves (figure 1). His chest X-ray was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

ECG on admission showing sinus tachycardia with moderately flattened T-waves.

Due to the combination of fever and mild respiratory distress, we performed an arterial blood gas. This showed a picture of respiratory alkalosis (on room air: pH 7.55; partial pressure of carbon dioxide 3.9 kPa; partial pressure of oxygen 8.4 kPa; bicarbonate 23 mmol/L).

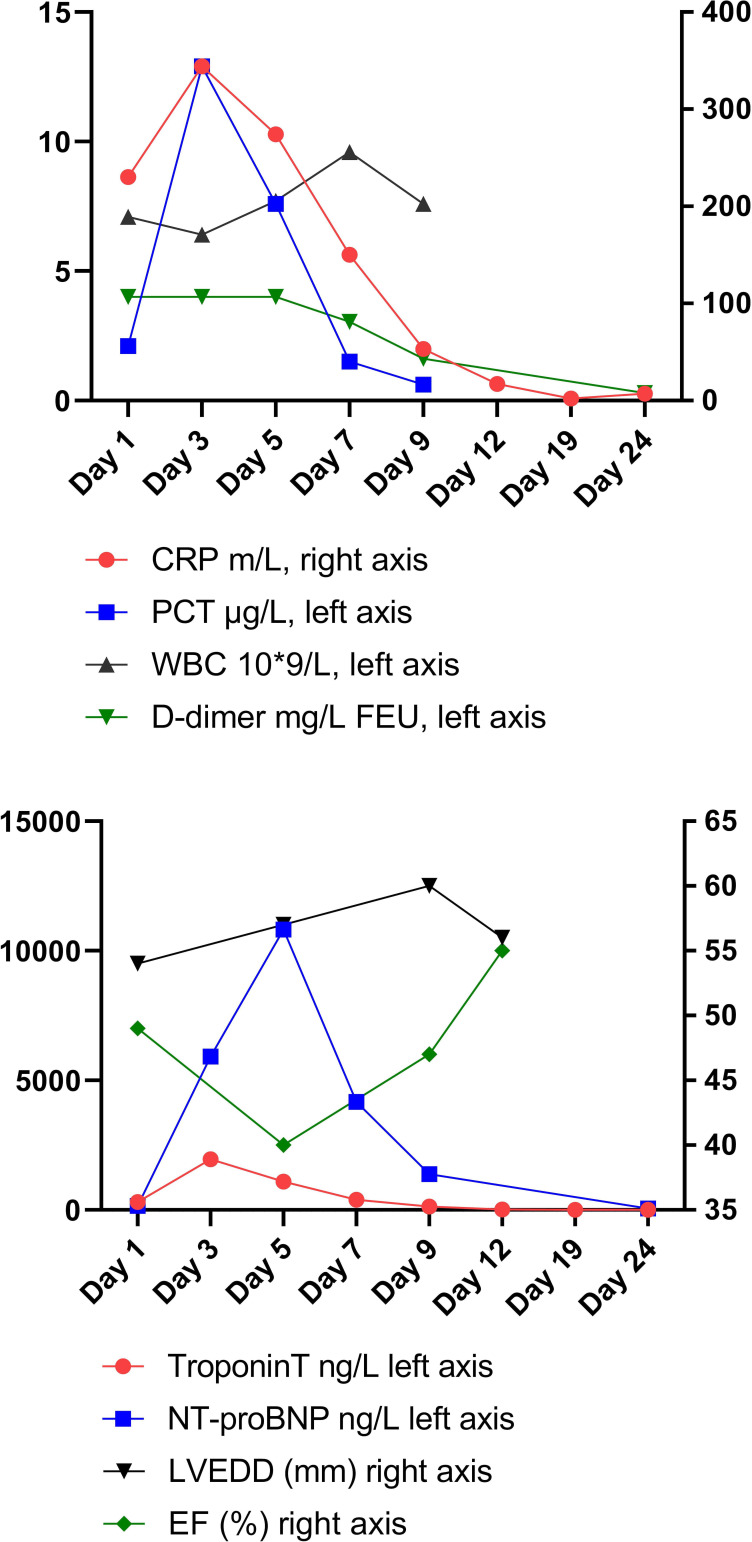

Routine admission blood tests showed an elevated C reactive protein (CRP) of 230 mg/L (0–5 mg/L) and procalcitonin of 2.1 μg/L (0–0.10 μg/L), with normal leucocytes at 7.1×109/L (3.5–11.0×109/L). The panel also revealed elevated troponin T (TnT) at 90 ng/L (0–15 ng/L). Blood was then further evaluated for N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which was also raised at 160 ng/L (0–85 ng/L). Echocardiography showed good ventricular function without hypokinesia and no significant valve pathology.

A CT of the neck was performed to assess the neck swelling. This showed subcutaneous oedema on the left side with multiple enlarged lymph nodes up to 2.0×2.7 cm in diameter.

Echocardiography was repeated on day 2 revealing a deterioration of the left ventricular function with reduced systolic function of 40% (video 1). The infectious parameters CRP rose to 344 mg/L and procalcitonin to 12.9 μg/L, while the leucocytes remained normal.

Video 1.

On day 3 after admission he was transferred to intensive care due to respiratory distress.

Differential diagnosis

Initially, on admission cellulitis on the neck was suspected and the patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics cefotaxime and clindamycin to cover for bacterial pathogens, including oral flora. He did not fulfil the criteria for sepsis.

Based on blood markers (raised TnT, raised NT-proBNP) and echocardiography, cardiac involvement was suspected. In the absence of chest pain myocardial infarction was thought to be less likely, but myocarditis was suggested as differential diagnosis. He received acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg and was observed with telemetry, and a CT angiogram and cardiac MRI was planned to clarify the diagnosis.

Despite a low clinical suspicion of COVID-19 with lack of contact and an atypical clinical presentation, a nasopharyngeal swab was performed due to the ongoing pandemic, which was positive on reverse transcription PCR for SARS-CoV-2.

Treatment

On day 3 after admission the patient’s condition deteriorated. He developed respiratory distress, saturating 94% on room air and was placed on 3 L/min of oxygen. Repeat arterial blood gas showed lactate of 3.2 mmol/L and partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) of 6.3.

He also had oliguria and hypotension (83/41 mm Hg) despite sufficient administration of fluids and therefore invasive haemodynamic monitoring was instituted. Transpulmonary thermodilution measurements using pulse-induced contour cardiac output (PiCCO) monitoring indicated a high-preload, hyperdynamic, vasodilated state. He received intravenous furosemide and intermittently required low-dose norepinephrine infusion to maintain a middle arterial pressure of >60 mm Hg, which normalised his urine output.

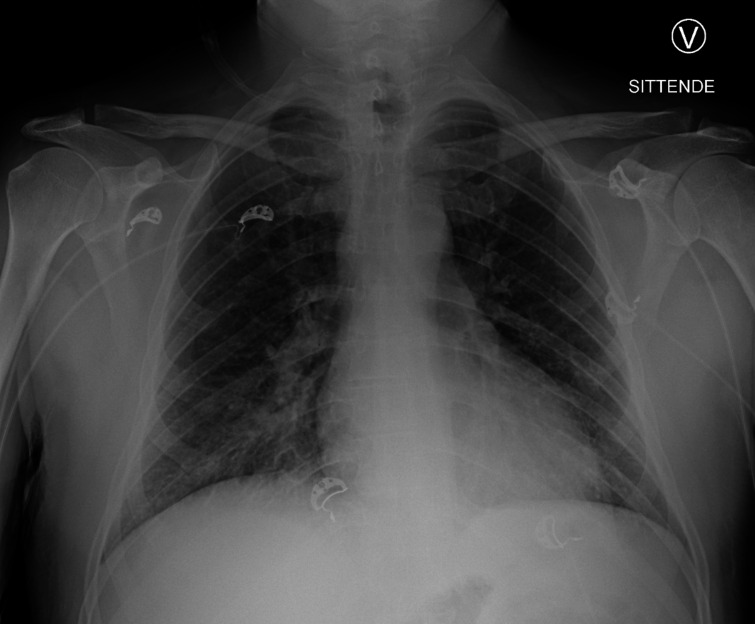

Continuous positive airway pressure was given intermittently, alternating with oxygen (2 L/min) by nasal cannula, on which oxygen saturation remained >93%. A repeat X-ray showed bibasal consolidations (figure 2). TnT and NT-proBNP rose to a maximum of 1959 ng/mL and 11 169 ng/L, respectively (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Chest X-ray on day 2 showing diffuse infiltrates in both lower lung fields.

Figure 3.

Timeline of echocardiography measurements and blood values. CRP, C reactive protein; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. FEU, fibrinogen equivalent units, PCT, procalcitonin, WBC, white blood cells, LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, EF, ejection fraction.

On day 5 after admission a cardiac MRI was performed revealing diffuse myocardial oedema (video 2) suggestive of significant acute myocardial injury. The CT angiogram showed no coronary artery stenosis.

Video 2.

His condition gradually improved and he was discharged 11 days after admission.

Outcome and follow-up

One week after discharge the patient was readmitted with unilateral, right-sided peripheral facial nerve palsy. Neurological examination and his general clinical status were otherwise unremarkable. We performed a cerebral CT scan which was normal. Spinal fluid examination revealed elevated protein of 1.0 g/L (0.2–0.4 g/L), IgG of 0.14 g/L (0.02–0.040 g/L) and mild mononuclear pleocytosis at 7×106/L (0–5×106/L).

He was empirically treated with doxycycline for suspected borreliosis, which is endemic in the region, and was discharged. However, subsequent analysis of blood and spinal fluid did not detect any anti-Borrelia antibodies. He had borderline raised C-X-C motif chemokine 13 (CXCL13) of 20.3 pg/mL (<20.0) in the cerebrospinal fluid, which does not differentiate between neuroborreliosis and other inflammatory processes. PCR on spinal fluid was negative for neurotropic agents, including SARS-CoV-2.

Using a recently validated assay6 we found high levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in the serum (19.1 µg/mL) and low levels in the spinal fluid (0.3 µg/mL). Antibody index, that is, spinal to serum ratio of specific IgG (0.3 µg/mL:19.1 µg/mL) divided by the spinal to serum ratio of the total IgG (0.14 g/L:13.3 g/L), was 1.47, indicating no definite intrathecal specific antibody production (cut-off <2.0). Antiganglioside antibodies (anti-GD1b IgG and anti-GM1 IgG) were detected in the serum obtained on readmission for facial palsy, but were not detectable in the serum obtained during his initial admission 2 weeks prior. Cerebral MRI performed after discharge was normal.

The patient subsequently recovered completely from his facial palsy. However, several months after admission he is still experiencing decreased exercise tolerance.

Discussion

Our case report describes a complex, multifaceted manifestation of COVID-19 in a previously healthy young man.

He initially presented with fever and neck swelling and received broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover for possible bacterial neck infection. However, blood and throat swab culture did not yield pathogens, and taken together with clinical and radiological findings we feel this is more consistent with SARS-CoV-2 reactive adenitis.

The myocardial dysfunction occurred during the initial febrile period, and although we did not perform a myocardial biopsy his otherwise comprehensive evaluation suggests he had viral myocarditis caused by COVID-19.

Acute myocardial dysfunction during the early course of COVID-19 has been retrospectively reported in 16%7–36%8 of patients and is associated with significantly higher mortality. Aetiology remains unclear, but cardiac damage in COVID-19 has been suggested to be attributed to stress-induced cardiomyopathy and immunological and microvascular damage.3 Case reports have documented that younger, previously healthy patients can develop significant regional cardiac injury due to acute coronary thrombosis in COVID-19, even with milder disease presentations.4 5 In our patient, the myocardial involvement was global, suggesting diffuse inflammatory damage as a more probable pathway than regional ischaemic dysfunction due to microvascular thrombosis or atherosclerotic plaque rupture.9 A particularity of the present case is the significant amount of myocardial injury, as reflected by an increase in TnT to >3× upper limit of normal combined with ECG and echocardiographic abnormalities, despite the patient’s young age and the absence of previous cardiovascular disease. The mechanisms underlying and the predisposition to COVID-19 myocarditis in young, otherwise healthy individuals remain poorly understood and are a research priority.3

Both central neurological manifestations, such as encephalopathy, seizures and ataxia, and peripheral nerve damage have been attributed to COVID-19, including frequent reports of loss of taste and smell, and rarely cranial neuritis mainly affecting eye movement.10–13 Whether SARS-CoV-2 actually displays neurotropism is currently not clear.10 In our patient, the low antibody index indicates there has not been viral replication within the central nervous system. The development of ganglioside antibodies during the course of the infection and the manifestation of Bell’s palsy only after he had recovered from the initial febrile infection support that the palsy has autoimmune pathogenesis.

Patient’s perspective.

I’m doing better, but I still feel reduced. Because I feel stiffness and tiredness in the body I’m still not able to go back to work. My hands are numb and with a sensation of tingling, especially in cold water. Otherwise I’m in good spirits.

Learning points.

Unusual presentations of COVID-19 present a risk of being overlooked, leading to delayed diagnosis, isolation and effective management of people with the infection.

Cardiac complications of COVID-19 infection can occur in otherwise healthy young people, and whether susceptibility reflects inflammatory response, autoimmune factors or another mechanism altogether remains unclear.

Bell’s palsy secondary to COVID-19 infection can occur and is likely to be of autoimmune pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bergen COVID-19 Research Group for their valuable input in the conceptualisation and writing of this case report: Rebecca Jane Cox, Karl Albert Brokstad, Florian Krammer, Nina Langeland, Helene Skjefte, Kristin Greve Isdahl Mohn, Camilla Tøndel, Fabian Åhrberg, Nicolai Maroni Johannessen, Lebaneng Abel, Jonas Torp Ohlsen and Siri Marie Blomberg.

Footnotes

Contributors: All five authors fulfil the authorship criteria. EHD, KAM and BB contributed to the conception of the case report, acquisition and interpretation of data, drafting of the article, as well as critically revising it for important intellectual content. CAV and DC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and critically revising it for important intellectual content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.del Rio C, Collins LF, Malani P. Long-Term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:1723–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.19719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. . Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:1017–32. 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topol EJ. COVID-19 can affect the heart. Science 2020;370:408–9. 10.1126/science.abe2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranard LS, Engel DJ, Kirtane AJ, et al. . Coronary and cerebral thrombosis in a young patient after mild COVID-19 illness: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2020;4:1–5. 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho JS, Sia C-H, Chan MY, et al. . Coronavirus-Induced myocarditis: a meta-summary of cases. Heart Lung 2020;49:681–5. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amanat F, Stadlbauer D, Strohmeier S, et al. . A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat Med 2020;26:1033–6. 10.1038/s41591-020-0913-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. . Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:533–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei J-F, Huang F-Y, Xiong T-Y, et al. . Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with COVID-19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart 2020;106:1154–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giustino G, Croft LB, Stefanini GG, et al. . Characterization of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2043–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. . Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. . Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2268–70. 10.1056/NEJMc2008597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z, et al. . Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:18–22. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Méndez-Guerrero A, Rodrigo-Rey S, et al. . Miller Fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology 2020;95:e601–5. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]