Abstract

Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma (CAF) is a rare benign tumour originating from the aponeuroses of tendons and their bony insertions. A 15-year-old student presented to his general practitioner with a 1-year history of a progressively enlarging painless finger swelling. The lesion was excised by the local paediatric orthopaedic service and recurred over the course of the following 4 months. Histology confirmed a diagnosis of CAF. He was referred to our specialist hand surgery service and the lesion was excised along with the ulnar lateral band and the overlying skin. At 9 months, there was no clinical evidence of recurrence. We are the first group to report the potential benefit of including of the overlying skin in the histological specimen to reduce the residual disease burden. Our case illustrates the technical challenges and considerations of removing a large, recurrent CAF of the hand and highlights the importance of centralised specialist care.

Keywords: plastic and reconstructive surgery, paediatric surgery

Background

Many hand tumours exist, affecting the adult and paediatric populations, and the majority are benign.1 2 They require the expertise of specialist multidisciplinary teams including hand surgeons, radiologists, specialist nurses, histopathologists and both hand and play therapists.3 Hand tumours may impair function of the hand due to the mass effect of the tumour and the morbidity associated with surgical resection.4

We present a case of calcifying aponeurotic fibroma (CAF), a rare paediatric tumour with a high propensity to recurrence and subsequent dysfunction, minimised by a collaborative approach to management at a specialist centre.3 5 6 CAF is a benign tumour originating from the aponeurosis (fibrous connective tissue) of tendons and their bony insertions.7 Histologically, there are both fibrous and cartilaginous components, the latter, due to the presence of chondroid cells, is responsible for the characteristic calcification of the tumour.7 8 They are typically less than 3 cm in maximum diameter, occur on volar surfaces of the palms and soles of the feet and are not associated with traumatic injury.6 9 They usually present as a painless mass and are considered extremely rare with unknown incidence or prevalence.6 8

Our case highlights some unusual presenting features of CAF, illustrates the technical challenges and considerations in removing a large recurrent CAF of the hand, and highlights the importance of centralised specialist care in the context of an evolving model of hand surgery service provision in the UK.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old, left hand dominant student was referred with a recurrent lesion of the dorsum of the middle phalanx of the left middle finger. He had no significant medical history or regular medication and was a keen rugby player. He presented to his general practitioner (GP) with a 1-year history of a progressively enlarging painless swelling. This followed a traumatic injury to the left middle finger proximal interphalangeal joint sustained when accidentally hitting their hand against a metal fence. A further injury was sustained when the patient trapped the same finger in a car door 8 weeks later. On examination, he had a firm 3 cm smooth oval swelling on the dorsum of the middle phalanx of the left middle finger. The swelling was non-tender on palpation, full range of movement was preserved and the digit was neurovascularly intact. Plain radiographs identified a soft tissue swelling with calcification projected within the soft tissues and no evidence of bony erosion or old fractures (figure 1A). He was managed expectantly and, 4 months later when the lump had not resolved, he was referred to the local paediatric orthopaedic service.

Figure 1.

Plain radiographs of left hand (A) preoperative (primary surgery) (B) preoperative (revision surgery).

After clinical assessment, further imaging was arranged and he was booked for an ultrasound scan. Ultrasonographic imaging found non-specific mixed echogenicity with internal vascularity, no bony erosion and suggestion of tendinopathy of the central slip insertion to the base of the middle phalanx. He was scheduled for a procedure with a provisional diagnosis of a tenosynovial giant cell tumour and the lesion was excised 6 months later under a general anaesthetic. The patient was protected in a splint for 2 weeks and the histology revealed a diagnosis of CAF. There were no immediate postoperative complications, however, over the course of the following 4 months the lesion rapidly recurred to effectively the same preoperative dimensions. The patient had an MRI scan 9 months after surgery, which provided further information regarding the morphology of the recurrence and its relations with adjacent anatomical structures. The radiologist described the lesion as a bilobed subcutaneous tissue mass, larger than measured on preoperative imaging, with no sign of adjacent tissue infiltration, however, scalloping of the middle phalanx was noted (figure 2). The patient did not undergo a further procedure at the initial institution and was subsequently referred to our tertiary hand unit by his GP, where he was seen 1 month later.

Figure 2.

MRIscan characterising a mass lesion in the deep subcutaneous tissues at the dorsal aspect of the middle phalanx of the left middle finger (top: coronal plane, bottom: axial plane).

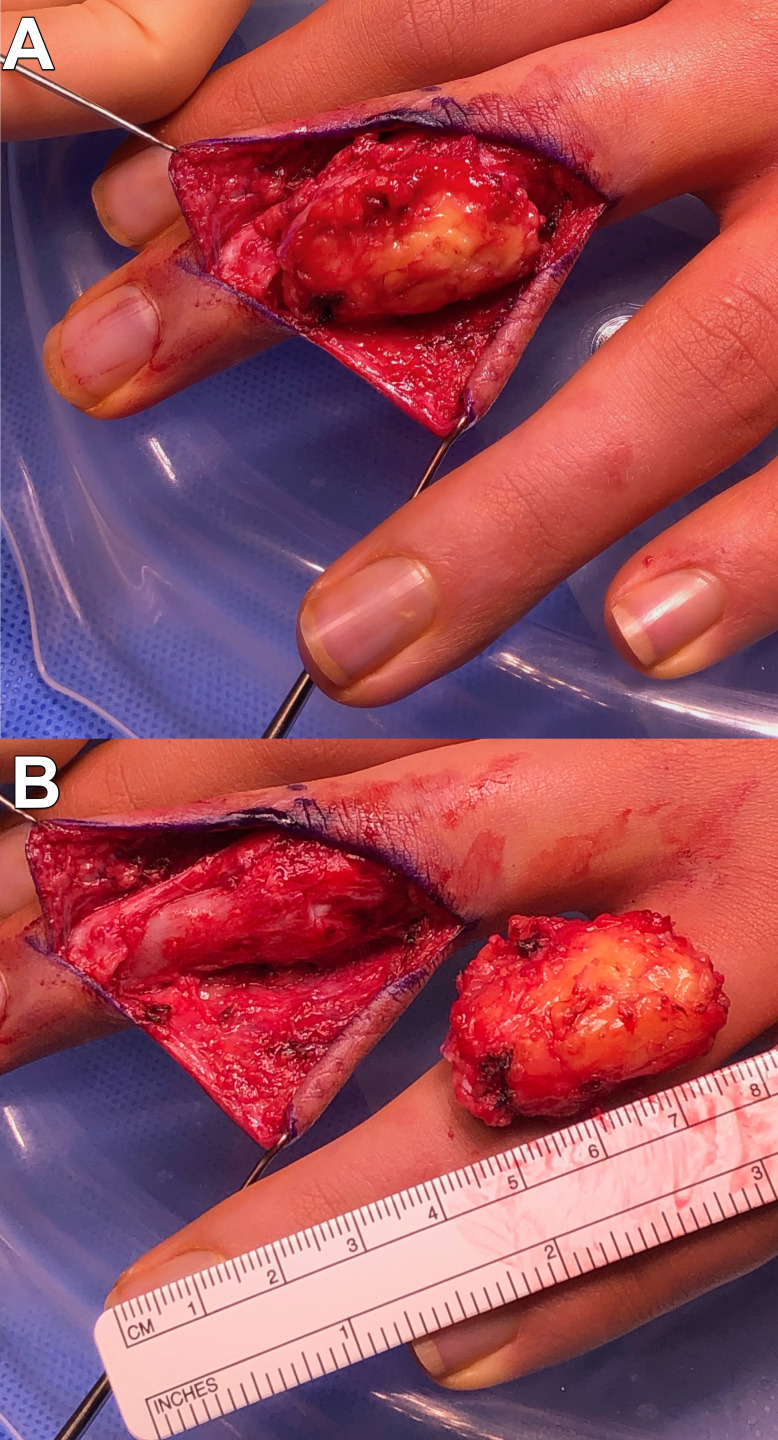

On assessment, active range of motion was preserved but the patient had symptoms of aching and stiffness, particularly when writing (figure 3). A repeat plain radiograph was performed which excluded bony invasion (figure 1B). The tumour was surgically excised several weeks later with preservation of the ulnar neurovascular bundle, where the tumour extended volarly (figure 4). The tumour had invaded the ulnar lateral band in extensor zones II–III which was sacrificed and excised en bloc with the tumour. The margins were macroscopically clear intraoperatively. The overlying skin tissue was also excised, the extensor apparatus reconstructed and the wound was closed. There were no postoperative complications and, on review in clinic 3 months later, he had a full range of movement. Sensation was intact and he was permitted to resume contact sport including rugby. Histology confirmed the previous diagnosis of CAF, with spindled cells in an infiltrative growth pattern, and positive deep margins. The excised skin tissue showed dermal scarring consistent with the previous surgery and additionally areas of spindled cell proliferation in the subcutis in close approximation with dermis. Nine months postsurgery there was no clinical evidence of recurrence.

Figure 3.

Digital photography of recurrent calcified aponeurotic fibroma pre-revision surgery.

Figure 4.

(A) Intraoperative photography of dissected tumour in situ; (B) intraoperative photography of excised specimen with resultant soft tissue defect.

Investigations

The patient had been investigated with multiple imaging modalities over a 3-year period prior to referral to our hand surgery service. Their initial investigation was a plain radiograph 5 months postinjury, which was reported as a calcified soft tissue swelling consistent with an ‘old haematoma’. While plain radiographs are a key initial investigation for investigating bony pathology in the hand, this modality provides limited data, even with digital radiographs, for investigating soft tissue lesions.10 However, in this case the presence of calcification does indeed provide useful diagnostic information as CAF is a calcified lesion (figure 1).7

The patient was observed and, as the lump did not resolve, 4 months later an ultrasound scan was arranged which provided further anatomical details of the lesion and adjacent tissues. Ultrasonography is a useful tool for investigating soft tissue lesions of the hand and identifying the anatomical structures involved. However, despite high contrast resolution, the quality of images and reports are limited by the operator’s scanning skill and findings are often non-specific.10

MRI provided detailed anatomical information of the recurrent lesion including size (2 cm (transverse)×0.5 cm (anteroposterior)×3 cm (craniocaudal)), precise location and relationship with adjacent tissues (figure 3). MRI has the highest contrast resolution of any cross-sectional soft tissue imaging modality; however, it is associated with increased costs and availability may be limited.10

Once surgically excised the primary and recurrent specimens were sent for histopathology and a tissue diagnosis of CAF was confirmed in both instances. Histopathology is considered the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic modality for tumours providing a reliable tissue diagnosis, with an adequate sample, and correlated with other investigations.4 7

Differential diagnosis

A tissue diagnosis was established prior to this patient’s referral to our hand surgery service. However, a provisional diagnosis of a tenosynovial giant cell tumour was considered by the tertiary paediatric orthopaedic service prior to surgery. Tenosynovial giant cell tumours (of the tendon sheath) are the most common soft tissue tumours of the hand distal to the metacarpophalangeal joints and the second most common soft-tissue tumour of the hand after ganglion cysts.1 11 However, they usually occur in later life and have rarely been reported in the paediatric patient population.11 12 After considering ganglion cysts as a differential, there are a plethora of rare tumours which occur in the hand including those of cartilage, bone, vascular, fibrogenic and miscellaneous origin.1 2 Malignant tumours such as Ewing’s sarcoma may present as a lump and must be considered in the differential.2 They often demonstrate hallmark features including invasion into local anatomical structures that may be detectable on imaging.2

Treatment

Surgical

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for presumed benign tumours of the hand which are symptomatic and causing functional impairment.4 The primary procedure excised the well-circumscribed lesion through a curvilinear dorsal incision. No margins were taken and anatomical structures were left intact. Following recurrence, access was gained through an incision along the previous surgical scar and the lesion was excised with the aforementioned macroscopically infiltrated extensor apparatus component.

Hand therapy

In order to regain function postoperatively, specialist hand therapy is often required to assess range of motion, provide specific therapeutic exercises and prevent stiffness.13 14 As the patient’s initial surgery was not at a hand surgery unit, they were not offered specialised hand therapy postoperatively. As the lesion rapidly recurred the patient became symptomatic with stiffness and difficulty writing. Excision of the recurrent lesion included the ulnar lateral band and involved tendon reconstruction. The patient received specialist hand therapy including application of a custom-made thermoplastic splint in order to facilitate rehabilitation. He developed mild swan-necking and mallet deformity postoperatively and this improved with splinting and mobilisation exercises. At discharge 5 months later, he was able to make a fist and had no functional impairment.

Supportive

Throughout the course of both treatments there was input from wider members of the multidisciplinary team including paediatric orthopaedic and plastic surgery nurses. Wound care was provided and where indicated simple analgesia was prescribed. The patient had clean-site surgery and did not require antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis. In younger children, play therapy can be offered to improve compliance perioperatively.15

At 9 months postsurgery the patient had no clinical signs of recurrence. This contrasts with the initial surgery where complete recurrence was evident 5 months postoperatively. The natural history of recurrence is reported as usually occurring rapidly following excision although may occur up to 3 years later.5 6 The patient and their family were educated regarding the potential for recurrence and to contact our unit for assessment if there were any concerns. The surgical wound healed well postoperatively with no complications and he was discharged from hand therapy following a good recovery of premorbid function.

The first reported cases of CAF were published by Keasbey and termed ‘calcifying juvenile aponeurotic fibroma’ as all known cases occurred in children.6 Indeed, most cases reported in the literature are children or adolescents, however, there are reports of elderly patients with the disease.16 17 CAF predominantly occurs on the palms and soles although there are isolated reports of other anatomical locations.5 We did not identify any reports in the literature of CAF occurring on the dorsum of the finger. As a rare tumour, it is often a histological diagnosis derived from excisional specimens, however, there is one report of diagnosis through core biopsy.18 We are also not aware of any recommendations regarding the overlying skin, which may serve as a source of recurrence if not included in the specimen. As the tumour is benign the general consensus in the literature is to preserve function of the extremity and avoid excision with excessive margins.4–6 There have been isolated cases of fibrosarcoma thought to be related to a CAF primary, however, histologically it may be difficult to differentiate between them.4 19 20

Guidelines for rare tumours such as CAF do not currently exist and the evidence base is largely derived from case reports.5 Indeed, we were unable to identify any general guidelines for the management of benign hand tumours which may be due to their heterogeneity and a relatively small number of specialist centres.1–3 The provision of specialist services in healthcare systems internationally is often organised as a ‘hub’ and ‘spoke’ model in order to centralise expertise while delivering selected specialist services locally.21 Hand surgery is not currently delivered in this manner in the UK and patients may receive hand surgery at non-specialist centres delivered by either plastic or orthopaedic surgeons.3 22 Not only is the surgery potentially delivered by a non-specialist surgeon, there is not the same infrastructure in terms of hand therapy and nursing staff as highlighted in our case. A recent report by the British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH) highlighted the lack of a hub and spoke service configuration and recommended its implementation.22 This model is gradually being adopted for hand surgery in the UK and is high on the agenda of the hand surgery community.23 Indeed, the reorganisation of hand surgery services and the hub and spoke model featured as the topic for the 2020 BSSH Pulvertaft Prize.24 Critically, GPs must be aware of the new referral pathways so that patients are directed to the most appropriate service.

This case illustrates the potential benefits of delivering highly specialist hand surgery services, such as rare tumour management, with an experienced multidisciplinary team. CAF is a rare tumour with a growing evidence base which is largely derived from single cases or small case series.

Patient’s perspective.

I don’t remember the exact moment when I noticed the growth on my finger; it just kind of appeared. My friends called it my pregnant finger as it looked like my finger was pregnant because of the lump. The lump on my finger didn’t get bigger unless it got whacked or trodden on which only happened a few times during some sport events. All in all, it didn’t really bother me apart from it made writing more strenuous. Originally, I had surgery on it at Kings but it grew back after a few months. Then in December 2019 I had a second surgery on it. This time it was fully removed and my finger is back to normal size. I had some therapy sessions on my finger, which helped me get almost my whole range of movement back. I don’t have to wear any protection on my finger and I have now been cleared to go back to playing sport. I am glad I had the surgery done as my finger is much better and am grateful to all the people who helped me with my surgery and recovery.

Learning points.

Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma may present atypically and a high index of suspicion is required for calcified soft tissue lesions of the hand.

Recurrence is common and damage to, or involvement of, surrounding anatomical structures may necessitate reconstruction.

Inclusion of the overlying skin in the histological specimen may reduce the residual disease burden.

Hand surgery provision in the UK is changing with adoption of the hub and spoke model.

Hand tumours may be more appropriately managed at specialist hand surgery centres.

Malignancies of the hand are very rare but must be excluded through investigation when clinically warranted.

Footnotes

Twitter: @innovateplastic

Contributors: MG lead the project and contributed to the conception, design, analysis and manuscript drafting. Approved the final submission. LC contributed to the conception, design, analysis and manuscript drafting. Approved the final submission. JI acted as the senior author and contributed to the conception, design, analysis and manuscript drafting. Approved the final submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tang ZH, Rajaratnam V, Desai V. Incidence and anatomical distribution of hand tumours: a Singapore study. Singapore Med J 2017;58:714–6. 10.11622/smedj.2016147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon MJK, Pogoda P, Hövelborn F, et al. Incidence, histopathologic analysis and distribution of tumours of the hand. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:182. 10.1186/1471-2474-15-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobby JL, Dias JJ. A review of hand surgery provision in England. J Hand Surg Br 2006;31:230–5. 10.1016/J.JHSB.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al. Green’s operative hand surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corominas L, Sanpera I, Sanpera-Iglesias J, et al. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma in children: our experience and a literature review. J Pediatr Orthop B 2017;26:560–4. 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keasbey LE. Juvenile aponeurotic fibroma (calcifying fibroma); a distinctive tumor arising in the palms and Soles of young children. Cancer 1953;6:338–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campanacci M, Bertoni F, Bacchini P. Aponeurotic Fibromatosis : Bone and soft tissue tumors. Berlin: Springer, 1990: 847–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim OH, Kim YM. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma: case report with radiographic and Mr features. Korean J Radiol 2014;15:134–9. 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.1.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schonauer F, Avvedimento S, Molea G. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma of the distal phalanx. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013;66:e47–9. 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindequist S, Marelli C. Modern imaging of the hand, wrist, and forearm. J Hand Ther 2007;20:119–31. quiz 31. 10.1197/j.jht.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozben H, Coskun T. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath in the hand: analysis of risk factors for recurrence in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:457. 10.1186/s12891-019-2866-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueno T, Ansai S-ichi, Omi T, et al. A child with giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. Dermatol Online J 2011;17:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong JMW. Management of stiff hand: an occupational therapy perspective. Hand Surg 2002;7:261–9. 10.1142/S0218810402001217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crosby CA, Wehbé MA. Early motion protocols in hand and wrist rehabilitation. Hand Clin 1996;12:31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He H-G, Zhu L, Chan SW-C, et al. Therapeutic play intervention on children's perioperative anxiety, negative emotional manifestation and postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1032–43. 10.1111/jan.12608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia Navas FM, Fernandez N, Lopez A, et al. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma of the sole of the foot in an elderly patient. Foot 2019;40:64–7. 10.1016/j.foot.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishio J, Inamitsu H, Iwasaki H, et al. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma of the finger in an elderly patient: CT and MRI findings with pathologic correlation. Exp Ther Med 2014;8:841–3. 10.3892/etm.2014.1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motta F, Scavo S, Vecchio GM, et al. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma: a core biopsy-based diagnosis. Pathologica 2018;110:307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lafferty KA, Nelson EL, Demuth RJ, et al. Juvenile aponeurotic fibroma with disseminated fibrosarcoma. J Hand Surg Am 1986;11:737–40. 10.1016/S0363-5023(86)80024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benichou M, Balmes P, Marty-Double CH. [Juvenile aponeurotic fibroma (Keasbey tumor) with metastatic course. Apropos of a case]. Ann Pediatr 1990;37:181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL. The hub-and-spoke organization design: an Avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:457. 10.1186/s12913-017-2341-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hand BSfSot Hand surgery in the UK: report of a working Party British Society for surgery of the hand (BSSH), 2017. Available: https://www.bssh.ac.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/professionals/Handbook/Hand%20Surgery%20in%20the%20UK%202017%20FOR%20PRINTING.pdf

- 23.Cadoux-Hudson D, Warwick D. How a nationalized health care system influences hand surgery practice: the United Kingdom perspective. Hand Clin 2020;36:171–80. 10.1016/j.hcl.2020.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hand BSfSot Pulvertaft Prize 2020: British Society for surgery of the hand, 2020. Available: https://www.bssh.ac.uk/professionals/bursaries_prizes.aspx#:~:text=Pulvertaft%20Prize,the%20President%20of%20that%20year