Abstract

Background

Low health literacy is common in general populations, but its prevalence in the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population is unclear. The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of low health literacy in a diverse IBD population and to identify risk factors for low health literacy.

Methods

Adult patients with IBD at a single institution from November 2017 to May 2018 were assessed for health literacy using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS). Demographic and socioeconomic data were also collected. Primary outcome was the prevalence of low health literacy. Secondary outcomes were length-of-stay (LOS) and 30-day readmissions after surgical encounters. Bivariate comparisons and multivariable regression were used for analyses.

Results

Of 175 IBD patients, 59% were women, 23% were African Americans, 91% had Crohn disease, and mean age was 46 years (SD = 16.7). The overall prevalence of low health literacy was 24%. Compared to white IBD patients, African Americans had significantly higher prevalence of low health literacy (47.5% vs 17.0%, P < 0.05). On multivariable analysis, low health literacy was associated with older age and African American race (P < 0.05). Of 83 IBD patients undergoing abdominal surgery, mean postoperative LOS was 5.5 days and readmission rate was 28.9%. There was no significant difference between LOS and readmissions rates by health literacy levels.

Conclusions

Low health literacy is present in IBD populations and more common among older African Americans. Opportunities exist for providing more health literacy-sensitive care in IBD to address disparities and to benefit those with low health literacy.

Keywords: health literacy, IBD, social determinants of health, surgery, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, is a chronic disease of unknown etiology that affects over 3.1 million people in the United States1 at costs of over $11 billion a year.2–4 Patients with IBD suffer from lifelong pain, bleeding, and malnutrition with added risks for cancers, bowel obstruction, and fistulizing disease. For these reasons, over 75% of IBD patients will face major, high-risk surgery in their lifetime with a wide range of consequences, including loss of intestines and ostomies.5,6 While IBD has historically been thought to affect populations of European white ancestry, over 30% of patients in current IBD populations may be African American.7–9 Within this growing population, significant disparities in health outcomes are emerging, including higher readmission rates, longer length-of-stay (LOS), and higher complication rates than white IBD patients after major surgery.10–12 The factors contributing to these disparities are incompletely understood but may include modifiable factors such as health literacy.

Health literacy, which is defined as “an individual’s capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,” 13 is a known determinant of many health outcomes and offers a potential way to address disparities.14–18 Low health literacy is common in the United States with over 36% of the population having “basic” or “below basic” health literacy.19 Its role in determining clinical outcomes in IBD patients is poorly understood, but likely important when considering the large volume of information, options, and decision-making involved in IBD management.20 A recent study by Tormey et al found that limited health literacy was present in up to 40% of one IBD population21; however, this study did not assess the relationship of health literacy with other demographic characteristics nor included African Americans. Therefore, to our knowledge, health literacy has not been fully characterized in IBD populations that include minorities. Such knowledge would be crucial to the identification of patients who might benefit from literacy-based interventions, which have improved health outcomes in other chronic diseases such as diabetes22 and cardiovascular disease.23

The aim of this study was to characterize the prevalence of low health literacy in a diverse IBD population and to identify potential factors associated with low health literacy. We hypothesized that low health literacy exists in the IBD population and that racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of low health literacy are present between African American and white IBD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

We evaluated 175 English-speaking patients from November 2017 to May 2018 who had an endoscopic confirmation of IBD (Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis) in a tertiary-referral IBD center in Alabama. Included patients were 18 years or older and all genders. Patients with unreported race/ethnicity were excluded from study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved for a waiver of consent by our Institutional Review Board (IRB 300000305).

Health Literacy Screening and Instrument

Health literacy was assessed by a trained research assistant not involved in patient care during routine clinical visits for patients at the IBD Center using the NVS24 (Newest Vital Sign). The NVS is a well-validated health literacy assessment that tests reading and numeracy. Patients are given a standardized ice cream nutritional label and asked 6 questions that focus on caloric and nutritional intake. The NVS is scored on a scale of 0–6 with each correct answer equating 1 point. Low health literacy is defined as a score between 0 and 3. Administration of each NVS test takes approximately 5 minutes total.

Patient and Procedure-Level Variables

All 175 patients had age, gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance recorded in their charts. A brief easy-to-read, multiple-choice survey (Appendix 1) was mailed to patients to assess employment, household income, household size, and education level. Social determinants of health (median income, % married, median home value, % employed, and % with at least a high school diploma) were extracted for all patients based on participants’ home zip codes. A neighborhood z-score was then calculated for each group and summed to obtain the neighborhood summary score.25 A positive score is associated with a more advantaged socioeconomic status whereas a negative score is associated with a more disadvantaged socioeconomic status. In addition, procedure-level characteristics such as the type of surgical or endoscopic procedure, if performed, were reviewed from the electronic medical records.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of low health literacy as measured by NVS (NVS scores 0–3). For those patients who had major surgical encounters, additional secondary outcomes were evaluated and included postoperative LOS and 30-day readmissions. These measures were evaluated to assess the potential impact of health literacy on surgical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Included patients were stratified by race/ethnicity to white and black/African American for the analysis. Descriptive statistics along with chi-square or Fisher Exact, Wilcoxon Ranked Sum, f tests, and bivariate analysis were used to describe the study population. Multivariable stepwise analysis produced odds ratios for low health literacy using logistic regression models adjusting for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Additional graphs were generated from the regression analysis to visually represent the predicted probability of having low health literacy by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Statistical significance was determined at an alpha level less than or equal to 0.05 and 0.167 for post hoc tests. All analyses were completed using SAS v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 175 patients with IBD participated in this study. Patient and procedure-level characteristics of the study population stratified by race/ethnicity are summarized in Table 1. Of 175 patients, 135 were white (77%) and 40 patients were African American (23%). Females represented 59% of the entire cohort. The mean age was 44 years (SD 15.7) for African Americans and 47 years (SD 17.1) for whites. Eighty-seven percent of African American patients had Crohn disease and 92% of white patients had Crohn disease. Eighty-three patients (47.43%) underwent abdominal surgery which spanned from July 2015 to August 2018. The remaining patients had either outpatient anorectal procedures (2.86%) or endoscopic studies such as colonoscopies (49.71%). The neighborhood summary scores were −1.6742 for African American participants and 0.4961 for white participants indicating a more disadvantaged socioeconomic status for African Americans with IBD.

Table 1.

Demographics and Socioeconomic Characteristics of IBD Population

| Black or African American (N = 40) | White or Caucasian American (N = 135) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVS score, m (SD) | 2.6 (2.0) | 4.3 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Age, years, m (SD) | 44 (15.7) | 47 (17.1) | 0.47 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.17 | ||

| Female | 20 (50.0) | 84 (62.22) | |

| Male | 20 (50.0) | 51 (37.78) | |

| Marriage status, n (%) | 0.036 | ||

| Divorced | 3 (7.5) | 10 (7.41) | |

| Married | 14 (35) | 79 (58.52) | |

| Separated | 1 (2.5) | 2 (1.48) | |

| Single | 21 (52.5) | 41 (30.37) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 3 (2.22) | |

| Insurance type, n (%) | 0.008 | ||

| Charity care | 6 (15) | 4 (2.96) | |

| Medicaid | 4 (10) | 4 (2.96) | |

| Medicare | 7 (17.5) | 18 (13.33) | |

| Private insurance | 22 (55) | 105 (77.78) | |

| Uninsured | 1 (2.5) | 4 (2.96) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.31 | ||

| Crohn disease | 35 (87.5) | 125 (92.59) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 5 (12.5) | 10 (7.41) | |

| Surgery status, n (%) | 0.94 | ||

| Abdominal surgery | 19 (47.5) | 68 (50.37) | |

| Anorectal surgery | 1 (2.5) | 3 (2.22) | |

| Colonoscopy | 14 (35) | 44 (32.59) | |

| Employment, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| Employed full time | 1 (13.7) | 13 (26) | |

| Employed part time | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Not employed | 1 (16.7) | 14 (28) | |

| Retired | 3 (50) | 17 (34) | |

| Student | 1 (16.7) | 4 (8) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.35 | ||

| No high school diploma | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 2 (33.3) | 9 (15.5) | |

| At least some college | 4 (66.7) | 48 (82.8) | |

| Income, n (%) | 0.23 | ||

| $100,000 or more | 1 (16.7) | 17 (34) | |

| $40,000–$99,999 | 1 (16.7) | 18 (36) | |

| <$40,000 | 4 (66.7) | 11 (22) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | |

| Neighborhood z-score | −1.6742 | 0.4961 |

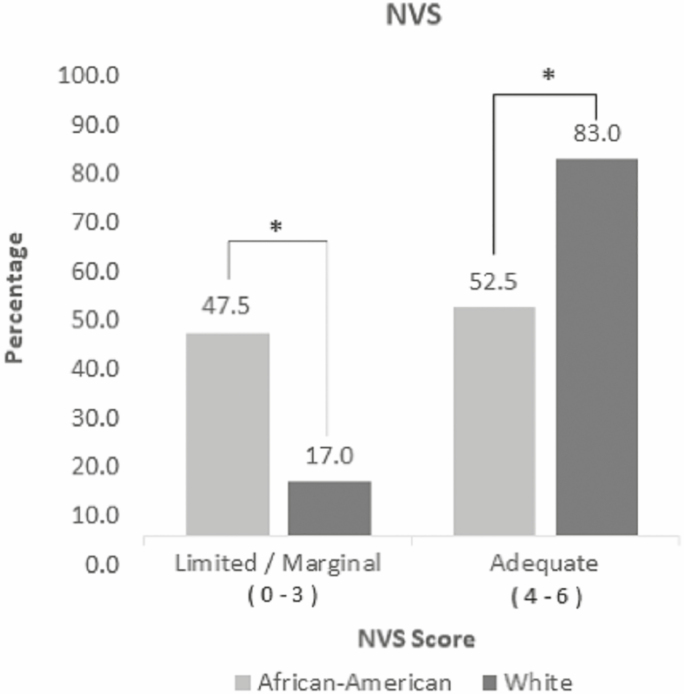

Low health literacy was present in the IBD population. For the entire cohort, 24% of patients had low health literacy. When stratified by race/ethnicity, 47.5% of African American patients had low health literacy compared to 17.1% for white patients (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). The mean score on the NVS was 2.6 (SD 2.0) for African Americans vs 4.3 (SD 1.7) for whites (P < 0.001). Mean age was 50.2 (SD 17.0) years for low health literacy patients and 44.8 (SD 12.3) years for those with adequate health literacy (P = 0.06). Male patients had a greater prevalence of low health literacy compared to female patients (54.8% vs 45.2%, P = 0.05).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of health literacy levels by race/ethnicity. The proportion of each level of health literacy is expressed as a percentage. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

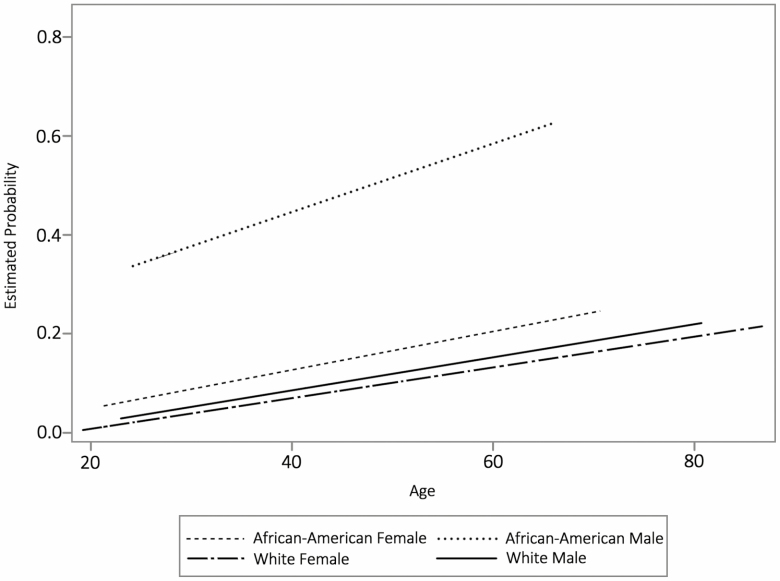

On adjusted analysis for health literacy, African American race remained significantly associated with low health literacy (odds ratio: 5.25, P < 0.01) (Table 2). Older age was also significantly associated with lower health literacy scores (P = 0.01). For every year in age, the probability of having low health literacy increased by 0.15% or 15%. For every year in age, the probability of having low health literacy for white patients increased by 0.12% or 12%. For ever year in age, the probability of having low health literacy for African American patients increased by 0.41% or 41% (Fig. 2). Gender was not significantly associated with health literacy (P = 0.08). On analysis of survey data, 56 (32%) of patients returned surveys. Of these respondents, 16.1% of overall respondents (n = 9) had low health literacy with 11.1 (n = 1) of low health literacy patients being African American. When characterizing low health literacy patients by education level, income, and employment status, the majority (56%) had an education level of high school or less (P = 0.01), the majority (56%) had an income of <$40,000 per year (P = 0.1), and only 11% were employed full time (P = 0.5).

Table 2.

Risk Factors Associated With Low Health Literacy on Multivariable Analysis Adjusting for Age, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity

| Odds Ratio Estimates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Wald | ||||

| Effect | Point Estimate | Confidence Limits | P | |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.01 |

| African American vs white | 5.25 | 2.42 | 11.4 | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Estimated probability of low health literacy by age, race, and gender. Patients were grouped into 4 categories based on race and gender. The graph demonstrates how age affects the probability of low health literacy by each category.

On analysis of secondary outcomes for IBD patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, the overall mean postoperative LOS was 5.5 (SD 4.5) days for the 83 patients who underwent surgery. LOS was not significantly different between low and adequate health literacy patients (5.2 vs 5.6 days, P = 0.7) (Table 3). Twenty-four patients (28.9%) were readmitted: 5 with low health literacy and 19 with adequate health literacy. There was no significant difference in readmission rates between low and adequate health literacy IBD patients (20.8% vs 32.2%, P = 0.3) (Table 3). When stratified by race, African American patients had longer mean LOS (5.8 vs 5.4 days, P = 0.8) and fewer readmissions (15% vs 32.3%, P = 0.1) compared to white patients, but these were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes for IBD Patients Undergoing Surgery: LOS and 30-Day Readmissions

| Low Health Literacy (N = 24) | Adequate Health Literacy (N = 59) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS, mean (SD) | 5.2 (5.0) | 5.6 (4.3) | 0.7 |

| LOS, median (IQR) | 3.2 (2.0–7.8) | 4.3 (2.4–9.0) | 0.5 |

| Readmission, n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| No | 19 (79.2) | 40 (67.8) | |

| Yes | 5 (20.8) | 19 (32.2) |

IQR, interquartile range.

DISCUSSION

In this study, low health literacy was shown to exist in a diverse IBD population in the Deep South. Overall, 24% of IBD patients had low health literacy by NVS. African Americans with IBD, however, had a 2-fold higher prevalence of low health literacy at 47%. This number is comparable to the 40% prevalence rate of low health literacy observed by Tormey et al in their IBD population using the NVS.21 Our study also highlights that older age is associated with low health literacy. Taken together, older African American patients with IBD are at the highest risk of having low health literacy. To our knowledge, this is the first reported characterization of health literacy levels in a racially diverse IBD population. These findings are important as African Americans with IBD represent a growing and understudied population who suffer from major disparities in clinical outcomes.7,26,27 Targeting factors such as health literacy may offer an innovative way to address these disparities.

The role of health literacy as a mediator and moderator on health outcomes has been established in many non-IBD populations.28–30 In a systemic review, Berkman et al found that poor health literacy also partially mediates racial disparities in some outcomes with low health literacy being consistently associated with more hospitalizations, greater use of emergency care and poorer overall health status.31 Previous studies have examined additional factors associated with low health literacy and identified significant associations with older age,32 male gender,33 and lower socioeconomic status.32 While low health literacy is not confined to a single demographic group, it has been shown to be particularly prevalent among racial and ethnic minorities.19,34 One study found that the prevalence of low health literacy was 54% among African American patients recruited from internal medicine and geriatric clinics, which was notably higher than the 13% measured among their white counterparts.35 These findings are similar to the significant differences in prevalence of low health literacy found in our study between African American and white IBD patients.

One of the strengths of our study is that health literacy was assessed using the NVS, a well-validated instrument in English and Spanish that captures several different domains of health literacy (reading comprehension, interpretation, and numeracy). Unlike other instruments, the NVS is not self-reported and it is one of the most discerning and objective instruments to assess health literacy.36,37 A recent systematic review of health literacy in surgery38 including 51 studies showed that the NVS is the most commonly used instrument for assessment of health literacy in the surgical population. Currently, there are more than 200 validated health literacy instruments available at the Health Literacy Tool Shed.39 While each instrument has benefits and weaknesses, our study suggests that the NVS is a feasible instrument that can be administered quickly, even in a busy setting like a surgical clinic.

Low health literacy is important to recognize because it affects a patient’s ability to understand and use health information and medical instructions.40 In a cross-sectional study with 1460 patients with uncontrolled hypertension, patients with low health literacy were less likely to have chronic medications reconciled or to demonstrate understanding of instructions and dosing.41 In a systematic review of 16 articles on diabetes,42 Chen et al showed that in patients with low health literacy, the odds of having diabetic foot disease were twice as high compared to patients with adequate health literacy. Many health professionals are unaware of the large number of patients who have low health literacy.24 Identifying patients at increased risk for low health literacy is therefore an important first step toward the development and application of a more effective and inclusive healthcare model.

For IBD patients undergoing major surgery, health literacy may play an additional role in determining surgical outcomes and addressing disparities. Although the subset of patients that underwent surgery in our study was small, there were readmissions occurring in IBD patients with low health literacy. Studies have shown that African Americans with IBD have an increased risk for readmission after colorectal surgery10 and have a higher rate of Crohn-related hospitalizations when compared with white IBD patients.11 Patients with low health literacy have also been observed to have longer LOS after major surgery.43 While our study showed no statistically significant differences in LOS or readmission rates between low and adequate health literacy IBD patients, our findings are subject to type 2 error due to the small study population that underwent surgery. The high prevalence of low health literacy among African Americans with IBD is significant, however, and warrants further investigation as a driver for disparities observed in larger IBD surgical populations.10 Efforts to eliminate disparities may therefore potentially benefit from the use of health literacy-based interventions.

While health literacy-based interventions targeting IBD have not yet been reported, interventions exist in other fields. These interventions are based on improved patient education, communication, and engagement. In the recent VIPVIZA23 study, which was a randomized controlled trial to improve cardiovascular disease, patients in the intervention arm received a graphic representation of their carotid ultrasound plus a nurse phone call to confirm understanding. Patients in this intervention group had improved cardiovascular risk scores at 1-year follow-up when compared to control patients, demonstrating the role of enhanced patient education using pictorial representations. In another example, Rothman et al22 used a health literacy-based intervention to improve diabetic control with the greatest benefits observed in patients with low health literacy. In their intervention group, communication to patients was individualized using techniques that enhanced comprehension among patients with low literacy. Additionally, patients with low health literacy had their usual care supplemented with 1-to-1 educational sessions including counseling and medication management. After the intervention, patients with low health literacy were more likely than control patients to achieve goal HbA1c levels. These studies suggest that interventions to improve outcomes based on best practices in health literacy (ie, health literacy-based interventions) are effective.

IBD patients with low health literacy may benefit from similar health literacy-based interventions at clinic visits, procedures, hospital stays, and outreach after discharge.44 Use of health literacy principles include patient-centered communication with plain language (avoids jargon), “teach back” to confirm patient understanding and offers of help in filling out forms. Written information that is provided to patients needs to be formatted for reading accessibility/understandability and it should include pictures and graphics. All patient materials should be developed with input from patients and be constantly improved for comprehension and acceptance. Healthcare providers and healthcare systems should also ensure that patients with limited health literacy are given understandable and culturally appropriate instructions to reduce misunderstandings and potentially prevent negative outcomes. In a study on ileostomy patients, patients who received an intervention of preoperative teaching, in-hospital engagement, and postdischarge tracking had significantly lower readmission rates (21% vs 35% at baseline).45 In our institution, patient education materials were recently redesigned using information design techniques. Reading level and clarity were significantly improved and the majority of patients, including those with low health literacy, preferred the new patient education materials. Additional efforts to improve care are also on-going at the organizational level as healthcare systems are also responsible for making it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and healthcare services. In fact, the National Academy of Medicine has described 10 key attributes of a health literate organization46 and recommends that all patients (ie, universal cautions) be given help throughout their healthcare encounter.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted at a single institution in the Deep South and may lack generalizability to other IBD populations. Second, given its retrospective and cross-sectional design this study is subject to selection biases, although all patients with IBD were approached for health literacy measurements. Third, the negative association of health literacy with clinical outcomes such as LOS and readmissions are subject to type 2 error given the small study population. Fourth, the majority of patients had Crohn disease and generalizations about low health literacy prevalence among patients with ulcerative colitis are limited. Fifth, the secondary outcomes focused on surgical outcomes and not on other IBD-specific medical outcomes such as medication adherence. Lastly, our survey response rate was particularly low among patients with low health literacy which limits our ability to associate health literacy with additional socioeconomic factors. Ultimately, future studies are needed to build upon our study’s findings and to continue improving our understanding of how health literacy impacts patients with IBD.

Conclusions

Low health literacy exists in the IBD population. Older African Americans with IBD represent a subset at even higher risk for low health literacy. Important opportunities exist to improve care and to address disparities in IBD through health literacy-based interventions.

Supplementary Material

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Society of Black Academic Surgeons on April 28, 2018 in Birmingham, AL.

Funding: D.I.C. is supported in part by a K12 HS023009 (2017–2019) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) through the UAB Center for Outcomes and Effectiveness Research and Education (COERE) and Minority Health and Health Research Center (MHRC) and a K23 MD013903 (2019–2022) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ or the National Institutes of Health. T.C.D. is supported in part by 2 U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, et al. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among adults aged >/=18 years—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson TB, Ng E, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. The direct and indirect cost burden of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:1261–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1064–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, et al. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sewell JL, Velayos FS. Systematic review: the role of race and socioeconomic factors on IBD healthcare delivery and effectiveness. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:627–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veluswamy H, Suryawala K, Sheth A, et al. African-American inflammatory bowel disease in a Southern U.S. health center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahid SS, Mulhall AM, Gholson RD, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and African Americans: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gunnells DJ Jr, Morris MS, DeRussy A, et al. Racial disparities in readmissions for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) after colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walker CH, Arora SS, Colantonio LD, et al. Rates of hospitalization among African American and Caucasian American patients with Crohn’s disease seen at a tertiary care center. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2017;5:288–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giglia MD, DeRussy A, Morris MS, et al. Racial disparities in length-of-stay persist even with no postoperative complications. J Surg Res. 2017;214:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Institute of Medicine Committee on Health L. What is health literacy? In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mancuso CA, Rincon M. Impact of health literacy on longitudinal asthma outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:813–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, et al. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, et al. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cavanaugh KL, Osborn CY, Tentori F, et al. Performance of a brief survey to assess health literacy in patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bailey SC, Fang G, Annis IE, et al. Health literacy and 30-day hospital readmission after acute myocardial infarction. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Nces 2006-483. National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: US Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tormey LK, Farraye FA, Paasche-Orlow MK. Understanding health literacy and its impact on delivering care to patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tormey LK, Reich J, Chen YS, et al. Limited health literacy is associated with worse patient-reported outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone R, et al. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA. 2004;292:1711–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Näslund U, Ng N, Lundgren A, et al. ; VIPVIZA trial group . Visualization of asymptomatic atherosclerotic disease for optimum cardiovascular prevention (VIPVIZA): a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Afzali A, Cross RK. Racial and ethnic minorities with inflammatory bowel disease in the united states: a systematic review of disease characteristics and differences. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2023–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, et al. Racial disparities in utilization of specialist care and medications in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2202–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, et al. Diabetes numeracy: an overlooked factor in understanding racial disparities in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1614–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sentell TL, Halpin HA. Importance of adult literacy in understanding health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:862–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koster ES, Schmidt A, Philbert D, et al. Health literacy of patients admitted for elective surgery. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2017;25:181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miller-Matero LR, Hyde-Nolan ME, Eshelman A, et al. Health literacy in patients referred for transplant: do patients have the capacity to understand? Clin Transplant. 2015;29:336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, et al. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eneanya ND, Winter M, Cabral H, et al. Health literacy and education as mediators of racial disparities in patient activation within an elderly patient cohort. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:1427–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Welch VL, VanGeest JB, Caskey R. Time, costs, and clinical utilization of screening for health literacy: a case study using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) instrument. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shealy KM, Threatt TB. Utilization of the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) in practice in the United States. Health Commun. 2016;31:679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang ME, Baker SJ, Dos Santos Marques IC, et al. Health literacy in surgery. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4:e46–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harnett S. Health Literacy Tool Shed: a source for validated health literacy instruments. J Consum Health Internet. 2017;21:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Persell SD, Karmali KN, Lee JY, et al. Associations between health literacy and medication self-management among community health center patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen PY, Elmer S, Callisaya M, et al. Associations of health literacy with diabetic foot outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2018;35:1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wright JP, Edwards GC, Goggins K, et al. Association of health literacy with postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koh HK, Brach C, Harris LM, et al. A proposed ‘health literate care model’ would constitute a systems approach to improving patients’ engagement in care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nagle D, Pare T, Keenan E, et al. Ileostomy pathway virtually eliminates readmissions for dehydration in new ostomates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1266–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brach C. The journey to become a health literate organization: a snapshot of health system improvement. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240:203–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.