Abstract

PURPOSE:

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing reactive balance training (RBT) in continuing care retirement communities, as a part of typical practice in these facilities.

METHODS:

RBT, a task-specific exercise program, consisted of repeatedly exposing participants to trip-like perturbations on a modified treadmill to improve reactive balance, and subsequently reduce fall risk. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with retirement community residents (RBT participants) and administrators, to assess the organizational context, perceptions of evidence for falls prevention, and facilitation strategies that could improve the likelihood of implementing RBT as a falls-prevention program.

RESULTS:

Contextual factors such as leadership support, culture of change, evaluation capabilities, and receptivity to RBT among administrators and health leaders at the participating retirement communities could facilitate future implementation. The cost associated with RBT (e.g. equipment and personnel), resident recruitment, and accessibility of RBT for many residents were identified as primary barriers related to the intervention. Participants perceived observable health benefits after completing RBT, had increased awareness toward tripping, and greater confidence with respect to mobility. Across interviewees potential barriers for implementation regarding facilitation revolved around the compatibility and customizability for different participant capabilities that would need to be considered before adopting RBT.

CONCLUSION:

RBT could fill a need in retirement communities and the findings provide areas of context, characteristics of the intervention, and facilitation approaches that could improve uptake.

Keywords: balance training, older adults, mixed methods, falls

INTRODUCTION

Falls are the primary cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries among adults 65 and older in the United States (1). In 2015, costs associated with falls exceeded $50 billion (2), which is expected to grow as the population of older adults increases. Furthermore, up to 50% of falls among community-dwelling older adults are caused by tripping (3, 4), which require quick reactive movements to successfully avert a fall. Current falls prevention programs considered for older adults include strength training, education on falls, gait training, and Tai Chi (1, 5–8). While these exercises have been shown to improve overall strength, balance, mobility, falls, and quality of life (5), none of these exercises target the specific reactive skills needed to recover from a trip. An increasingly popular approach to reduce the number of falls from tripping is to improve the reactive balance response after tripping through training. This so-called reactive balance training (RBT) involves repeatedly exposing individuals to realistic trip-like perturbations in a safe, controlled manner. RBT, an example of perturbation-based balance training, improves the neuromuscular response after laboratory-induced trips, and reduces the risk of falls (9–12). This specificity has the potential for RBT to be much more potent for reducing trip-induced falls than programs more focused on general physical function. For example, while there is no clear guidance from the literature on the dosage of exercise required to reduce falls, more robust effects have been found after dosages of at least 50 hours (7). Conversely, studies employing RBT have reported lower fall rates, or sustained improvements in reactive balance, after 12 training sessions totaling six hours (13), after four training sessions totaling four hours (9), or even just one training session (10).

Previous studies on RBT targeting trip-related falls have been conducted in laboratory settings (9, 11, 14–16). Implementing RBT in the community, may facilitate reaching more fall-risk individuals who could benefit from RBT. However, its impact is highly dependent on the scale-up and adoption of RBT by settings that can reach the target audience, such as continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs).

We conducted a pilot controlled trial to investigate the initial efficacy of on-site RBT for older adults in CCRCs (13). As a part of this trial, we conducted interviews of CCRC administrators and residents examining the contextual factors that could guide the future translation of this approach into standard community practices. The purpose of this study was to use these data to evaluate the feasibility of implementing RBT in CCRCs as a part of typical practice in these facilities. The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework was used as the overarching conceptual model to understand the potential for RBT to be translated into practice. This framework considers implementation success to be a function of context, evidence, and facilitation (17). We report on the perceptions of CCRC administrators and residents who participated in our RBT trial related to feasibility, and barriers to adoption and implementation of RBT as a part of typical practice in these facilities.

METHODS

Semi-Structured Interviews

The work reported here occurred from October 2015 to July 2017. We interviewed key administrative staff and residents at four CCRCs that participated in our pilot-controlled trial for RBT in the Bryan/College Station, TX area (population of 200,000). All of these CCRCs had a dedicated space for exercise, and multiple exercise programs for their residents. As noted below, no residents from a fifth CCRC passed our screening, and thus no administrators from this CCRC were interviewed for this study. We were unable to identify any facility-related or resident-related characteristics to explain this occurrence.

From each participating CCRC, we targeted our interviewee recruitment efforts using a systems-perspective (18, 19) to include employees who would ultimately be responsible for implementing RBT and those with decision-making authority for introducing new programs and resources to the CCRC. As a result, we recruited employees at each CCRC who (1) were directly involved with RBT testing (i.e. activities director), (2) a health professional who could implement the program, and (3) an administrator with decision-making authority (i.e. manager). A total of eight CCRC employees completed the interview including three health promotion personnel and five administrative decision makers. Three of the administrative decision makers also had health promotion responsibilities at their respective sites. Administrator interviews were completed once all residents at the administrator’s site had completed their last session of RBT. The administrators were interviewed by a trained researcher with a semi-structured interview guide based on the PARIHS framework constructs of context, evidence, and facilitation (17, 20, 21). The 30-minute interview began with structured questions regarding administrator training and experience, then open-ended questions assessing the need for RBT, evidence needed to adopt RBT, the organizational context (including administrative support for RBT), barriers to implementation, perceived benefit of RBT, and questions related to potential facilitation strategies to improve uptake at other CCRCs.

To gain a greater understanding of resident experiences with RBT, participating residents completed a survey and participated in semi-structured interviews after completing all testing. The brief survey assessed quantitative resident perceptions of the ease of participation, enjoyment, and helpfulness of RBT, as well as normative beliefs relative to the potential reach of this type of program. During this survey, RBT participants were asked to rank their perceptions of RBT at the beginning of the program, and at the end of the program, on a scale of 1 (least favorable) to 5 (more favorable) to evaluate how their perceptions may have changed during the program. RBT participants were also interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide by a trained research assistant. The interview included open-ended questions about resident recruitment and engagement, program likes and dislikes, participant outcomes, and potential adaptations to RBT. The protocol was developed to facilitate resident recall of their perceptions of RBT at the beginning and end of the 12-session program. Interviews lasted 30 minutes. As a separate portion of this study, reported elsewhere (13), the efficacy of RBT against a Tai Chi control group, was examined. However, qualitative interviews only focused on RBT since resident perception and feasibility of Tai Chi has been previously studied (22–24).

Intervention Description

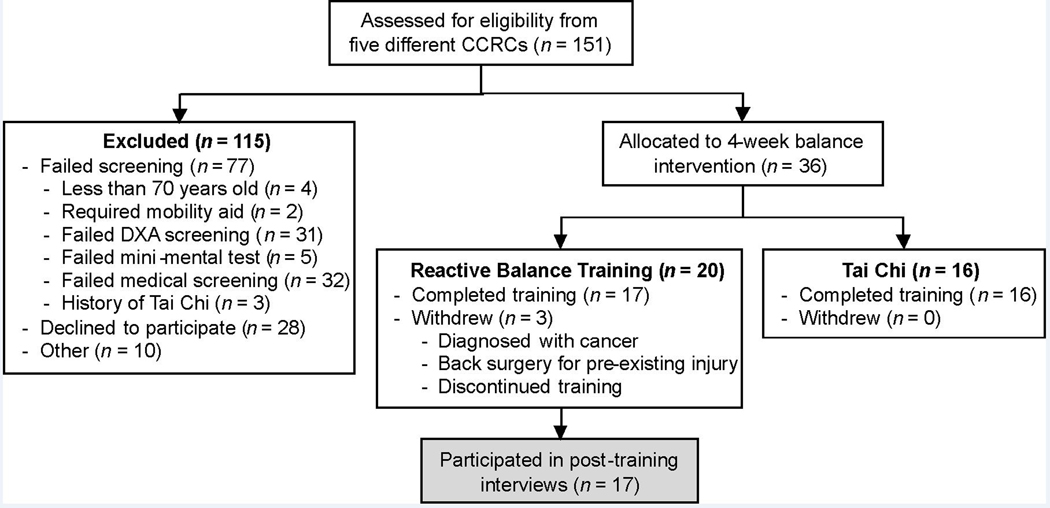

Residents from five CCRCs were recruited to participate in RBT through oral presentations, flyers, and word of mouth among residents and staff. Inclusion criteria required residents to (1) be at least 60 years old; (2) walk without the aid of an assistive device; (3) have a bone mineral density of the proximal hip of t ≥ −2.0, obtained from Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (Hologic Inc., Hologic Discovery W QDR series, Waltham, MA); (4) score at least 24 on the standardized mini-mental state exam (25); (5) pass a medical screening by a physician that excluded individuals with major unstable cardiopulmonary disease, or other progressive or unstable medical condition that could account for possible imbalance and falls; and (6) not have previously participated in Tai Chi classes (due to comparisons of balance interventions reported elsewhere (13)). A total of 151 residents (n = 47, n =27, n = 29, n =17, n = 31, from each CCRCs, respectively) expressed initial interest; 115 were excluded due to failing our screening, declining to participate, or having other personal circumstances that precluded their participation (Figure 1). One CCRC did not implement RBT for this study due to a lack of eligible participants. The 36 eligible residents from the four participating CCRCs were randomly assigned to participate in either RBT (n = 20) or Tai Chi (n =16 through randomization minimization (26). Of the 20 RBT participants, 17 completed all aspects of the project, including the interviews of interest here. Two of these 17 RBT participants reported having fallen two or more times in the past year, while 14 exhibited at least one clinical test of balance and mobility score that indicated a clinically-relevant increase in fall risk.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram depicting the number of participants assessed for eligibility, number that passed screening, number allocated to each intervention, and number used in analysis.

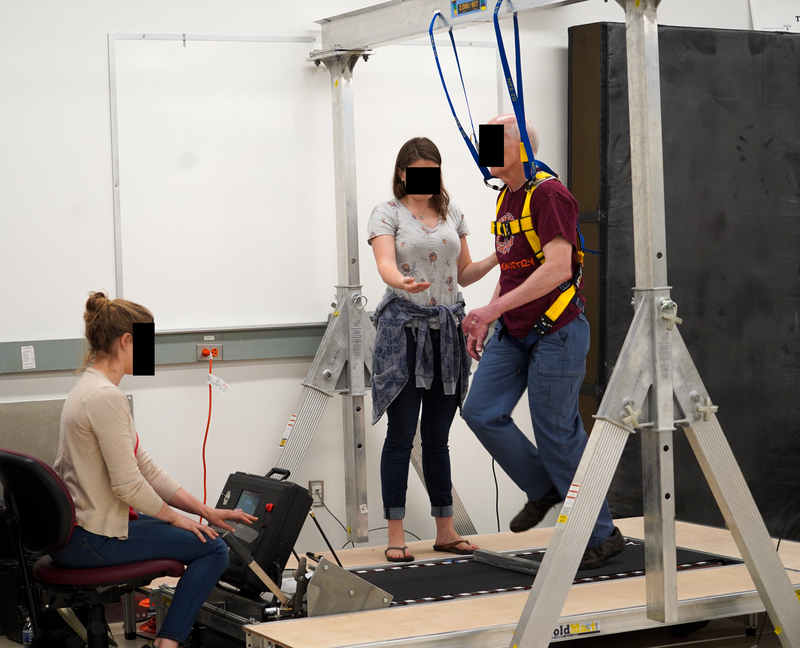

RBT participants performed RBT three times a week for four weeks, with each session lasting 30 minutes. Within each session, participants were exposed to approximately 40 trip-like perturbations on a modified treadmill, while wearing a fall prevention harness for safety (Figure 2). The biomechanical responses needed to recover from this treadmill perturbation is similar to the response needed to recover from an actual trip (15). At the start of each perturbation, RBT participants stood on a stationary treadmill with a slender, foam block (4×4 cm cross section) placed approximately 3–7 cm in front of their toes (to elicit a step over an obstacle, similar to that needed after a trip). Then, without warning, the treadmill belt would suddenly (~40 msec) accelerate backward to a trainer-selected speed, eliciting a forward loss of balance. Residents were instructed to, upon treadmill movement, step over the block and establish a stable walking pattern.

Figure 2.

Image depicting a participant successfully recovering from a perturbation during reactive balance training. The harness attached to the overhead gantry prevented a fall to the ground in case of an unsuccessful recovery.

Data analysis

Administrator and resident interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Content analysis was performed to divide transcribed interview responses to form meaning units (27, 28). Common meaning units were then grouped together to create underlying themes relative to perceptions of the RBT program and potential for adoption in typical CCRCs. For the administrator interviews, themes across each question were compared and grouped into larger, overarching themes relevant to the factors of the PARIHS framework. For the resident interviews, a thematic analysis was used to identify overarching themes relevant to participant recruitment, program enjoyment, and outcomes and through the lens of Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation definitions of characteristics of an innovation (i.e., relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, observability, testability (29, 30)).

Content analysis was performed by two independent researchers to minimize bias during interpretation of results. The qualitative analyses of administrator and resident interviews were performed independently. To ensure validity of the administrator and resident responses, the interviewer summarized the interviewee’s responses at several points during the interview to ensure agreement between the interviewee and the interviewer’s interpretation.

For the quantitative resident survey, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was performed to evaluate differences between resident perceptions at the beginning and end of RBT.

RESULTS

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing RBT in CCRCs. From administrator interviews, we investigated the facilities perspective related to fall prevention, how that might influence the adoption of RBT, the evidence needed to implement RBT, and facilitation of RBT in CCRCs. From RBT participant interviews, we identified major themes that arose describing participant’s perceptions of RBT.

Administrator qualitative interviews

Eight administrators from three of the four CCRCs that implemented RBT at their facility participated in the semi-structured interviews (Table 1). Administrators from one of the CCRCs were not able to participate in the semi-structured interviews due to scheduling conflicts. We identified major themes from the semi-structured interviews with administrators that are congruent with the PARIHS components of context, evidence, and facilitation that are hypothesized to influence successful implementation.

Table 1.

Roles of CCRC administrators who participated in semi-structured interviews.

| Current job title | Professional background | |

|---|---|---|

| CCRC 1 | Activities Director | Masters in health and nutrition |

| Health Professional | Nurse | |

| CCRC 2 | Activities Director | Professional certifications for CCRCs |

| Health Professional | Nurse | |

| Manager of healthcare division of CCRC | Registered Nurse | |

| CCRC 3 | Activities Director | Certified activities director |

| Health Professional | Nurse | |

| Manager of CCRC | Bachelor’s degree in Business with medical military experience |

Context

Culture of falls

Administrators reported a variety of ways by which their facilities track resident falls, such as filing incident reports, using fall tracking technology (i.e. individually-worn pendants that detect when an individual falls), informal tracking, or no tracking methods. Multiple administrators described incident reports or a manual fall log as the only way falls are monitored, however it is unclear how this data was used to evaluate residents’ individual risk of falls. For example, one individual said, “Oh well we usually find out [if a patient has fallen]. A lot of them, they can’t get back up, and so they need assistance getting up. So then we keep track as far as, on an individual basis, ‘Oh this person has fallen X number of times’ … but we don’t do statistics.”

Similar to the previous quote, many administrators expressed that despite having protocols in place, they still cannot capture all resident falls. One staff member said, “And in some instances, people don’t want us getting in their business because they’re still independent. A lot of times they will fall and they won’t tell us. They’ll figure out a way to get up or they’ll call family members to come help them. They’re embarrassed. So, it’s really difficult to have accurate information totally.” The remark about residents not informing staff about their falls was echoed by other administrators. Furthermore, fall tracking technology was also seen as flawed: “Pendants are not guaranteed to detect a fall…they were set so that they would detect a fall from bed, [but] anytime someone sat down hard, it would go off. It goes off to our pagers here. So, we know most of the falls we respond to. Are there still falls we don’t know about? Yes.” One administrator commented that it is not within their responsibilities to track falls as an independent living facility, therefore administrators are only aware of the falls they personally respond to.

Administrators expressed a desire to more accurately capture falls. For example, one administrator commented on the need to track resident falls, saying, “…often I’ve done that very thing, wanting a spreadsheet of specific places [of resident falls]. Because [resident falls] needs to be watched.”

Leadership Support for RBT

CCRC administrators agreed that key leaders in their organizations saw value in RBT while it was being offered at their facility. Additionally, administrators agreed that the leaders of their organizations would support RBT as a sustainable part of the services they provide, with one respondent saying, “we’re on board, yeah we welcomed it. Anything to help the residents, you know.” Another respondent mentioned that the leadership at the CCRC would prioritize a falls prevention program like RBT, but the timing of implementation may not be immediate, and would likely need a designated leader, saying “it would be a top priority, whether the [CRCC leadership] do it right now or not, no probably not … but if there was someone to lead it… I think they would be very on board with it. … you know as soon as someone falls a few times, they’re getting home health, you know, so it’s a priority.”

Receptivity to Change

CCRC administrators listed a number of current collaborators in professional networks that could help support the sustainable implementation of RBT, such as physical therapists and home health agency professionals. When asked what changes might occur if their facility chose to offer RBT regularly, most respondents said staff roles would need to be enhanced, with one respondent saying, “I think it would enhance the roles. I don’t think it would affect it in a negative way, I think it’d be a positive way. Enhancement of the roles. Yeah, [staff would] be more involved and they’d have more education as to fall prevention.” Administrators anticipated widespread acceptance of RBT by staff, saying, “I do think that we would appreciate it, I do think that it would be helpful,” and “I think we would accept it 100%. Anything to help [the residents].”

Evidence

Need for RBT

Although exact fall frequency is often unknown by CCRC staff and administrators, they still see a need for balance training programs for their residents. Many communities already had exercise programs in place, but few that specifically addressed balance and fall recovery. These programs included exercises such as a general chair exercise program, a chair Tai Chi program, water aerobics, and stretching. Even without explicit randomized controlled trial data, staff perceived the RBT training as effective or, at a minimum would fill a need specific to reducing falls that they felt may not be addressed by current programming.

Additionally, CCRC administrators described their perceptions of residents’ interest in RBT. Most administrators agreed that RBT aligned with resident preferences and filled a need in the resident desire to avoid falling. One participant commented, “One of [the residents’] biggest concerns is falling. They know that at any point in time, a fall can be a bad one and they can go into rehab if they’re lucky and they don’t hit their head. I would say in general…people are concerned about that.” However, there are residents that may not see the need for RBT as one administrator expressed, saying, “I don’t think they see the need. They’re in denial.”

When asked what type of evidence would be needed to consider using RBT as a sustainable offering at their facility, responses focused around two types of evidence: long-term effectiveness and generalizability of the program, particularly among different age groups and different facilities. One administrator said, “I can see different ages reacting to [RBT] differently”. Another commented, “The techniques that you’re developing could be walker appropriate too,” and suggested that evidence of RBT effectiveness among individuals with mobility aids might be helpful to increase the potential reach of RBT.

Facilitation

Implementation Concerns

Administrators overwhelmingly agreed that RBT is applicable to their setting, and when asked to consider potential implementation of RBT into regular community practice, CCRC administrators stated that improved resident balance, health, and /or safety would be benchmarks of success. However, a number of concerns were raised about the potential facilitation strategies needed to implement RBT in regular practice. These concerns included space availability, cost, resident recruitment, and staff training. Most of the respondents grouped these concerns together, saying “The only challenge of implementing would be cost of the apparatus and finding a space for it,” and “we would probably have to allocate more resources, finances towards training as well.” Another administrator elaborated on necessary training, saying “At this point I think [staff] would have to be trained. They’d have to get the information needed because they don’t have it at this point.” It was not clear from administrator responses if a new hire would be needed to conduct RBT at CCRCs or if current staff would be sufficient to deliver the program; responses were specific to each CCRC.

Resident recruitment was also mentioned as a facilitation challenge. When one administrator was asked what factors, other than evidence, need to be considered when deciding to implement a falls prevention programs, they responded “But the biggest thing is participation. So, to implement something, if they don’t like it and they’re not going to participate, we can’t force them to do it. So, it has to be an activity that they’re interested in. That would be my prime consideration. Because it’s very difficult to implement a program, especially if it costs money, and if, like, three people do it.”

RBT participant qualitative interviews

All 17 residents who completed RBT participated in the semi-structured interviews. Three major themes were identified from RBT participant interviews: (1) RBT participants had self-recognized health benefits as a result of training; (2) RBT may not completely align with the recreational and functional capabilities of CRCC residents, potentially limiting program enrollment and engagement; and (3) RBT participants offered key suggestions on how to increase RBT sustainability.

(1). RBT participants had self-observed health benefits as a result of training

Residents who participated in RBT noted benefits in their balance, independence, and confidence. After participating in RBT, residents noted an improvement in their balance based on an increased awareness of their environment, increased awareness of potential trip hazards, and perceived improvement in their balance recovery response. One RBT participant stated: “If I stumble or trip, then I will – my natural response will be better than it was prior to starting the training.” An increased awareness of the environment also led some residents to express an increased sense of independence. One RBT participant noted “Being aware of your environment … those were things I really didn’t think about before, so I think it gives you a little bit more independence.” RBT participants noted an increase in their mobility, exemplified by an RBT participant’s response stating “maneuvering around awkward spaces, I think [RBT] did that and I noticed that I’m doing things I couldn’t [have] always done most of the times.” Other RBT participants noted that RBT could offer increased financial independence since reducing falls would reduce health care costs. An increase in confidence arose from RBT participants feeling more secure about their ability to prevent falls and recover from a trip, if one were to happen. One RBT participant stated “It was just kinda good to see I could do the [RBT program]. That I was physically able to handle it.”

(2). Potential incompatibility with resident recreational and functional capabilities

Individual physical and functional limitations, as well as competing priorities, were among the main reasons why RBT participants thought their peers might not participate in RBT. One of the most cited reasons for limited participation was that residents might be physically restricted, reducing the trialability of the approach for a portion of the population. One resident summarized these thoughts by saying, “Well I mean physically [residents] couldn’t withstand [RBT]. The effect it has on their joints. I think most of them are maybe arthritic or maybe disabled in some other form.” In addition to potential physical limitations, many RBT participants thought that RBT participation could be limited because residents “… have gotten to that point where they’re dependent on something - walker, cane, whatever” suggesting a lower perception of relative advantage of RBT over alternative approaches to avoiding falls. While older adults might be limited in their physical capabilities, RBT participants noted that other residents might not be interested in the program because it is not compatible with their life stage. One RBT participant stated: “… some people at this point in life just may not feel like they want to start something new because you have to make a commitment.” Lack of RBT interest could potentially be attributed to the fact that “There’s a lot of people who are not willing to do anything uncomfortable,” as one RBT participant stated. Additionally, many RBT participants stated that they were too busy with other activities in their CCRC, which could have contributed to a lack of RBT interest—again reflecting the relative advantage of RBT when contrasted with other facility offerings. Nevertheless, while many reasons as to why other residents might not participate in RBT were discussed, those that did participate observed a number positive outcomes that underscored the likely utility of RBT programming for a segment of the resident population.

(3). RBT participants offered key suggestions on how to increase RBT sustainability

The majority of RBT participants suggested making RBT, and the positive outcomes associated with RBT, more observable through advertisement as a means of encouraging more residents to participate. Some RBT participants suggested including a testimony from past RBT participants to demonstrate the advantages to the program on activities such as daily walking. The importance of increasing the information presented to residents about RBT is summarized by one RBT participant’s interview, stating: “Explaining in fullness at the beginning, not just coming and saying we would like for you to participate. Explaining what the program’s about. Just the explanation would be a mind-changing thing because a lot of the people changed their mind after they signed up because they weren’t sure what it was [going to] be like.”

During their interview, RBT participants were asked if they would continue to participate in the program if it was continually offered at their facility. Thirteen of the 17 RBT participants stated that they would continue to participate in RBT if it was offered. Additionally, most RBT participants stated that they would prefer the program be offered weekly. The four RBT participants who did not want to continue participating in RBT stated it was because they did not have time, the treadmill caused too much anxiety, they disliked the harness, they saw no benefit to participation, or they would rather participate in Tai Chi.

RBT participant quantitative survey results

RBT participants reported statistically significant improvements in their perceptions of RBT in four of the six questions asking participants to compare their perceptions at the beginning and end of the program (Table 2). When asked to rate how easy RBT was to do (1 = Very Difficult, 5 = Very Easy), responses during the first week of the program were 3.06 ± 1.09 (mean ± standard deviation), and increased 1.24 points (p = 0.001) by the end of the program. When asked to rate how much RBT participants enjoyed RBT (1 = Not at All, 5 = Very Much), responses during the first week of the program were 2.82 ± 1.51 and increased 1.35 points (p = 0.002) by the end of the program. When asked how helpful RBT was in improving their overall quality of life (1 = Very Unhelpful, 5 = Very Helpful), responses during the first week of the program were 3.06 ± 0.97 and increased 1.12 points (p = 0.004) by the end of the program. When asked about their overall satisfaction with RBT (1= Very dissatisfied, 5 = Very satisfied), responses during the first week of the program were 3.94 ± 0.97 and increased 0.76 points (p = 0.014) by the end of the program. At the end of the program, two additional questions were asked. When asked if they thought RBT should be offered regularly (1= completely disagree, 5 = completely agree), participants responded 3.82 ± 1.29. When asked how many people might participate in RBT (1 = None, 2 = A few, 4 = Most, 5 = All), participants responded 2.82 ± 0.81.

Table 2.

Summary of results from reactive balance training quantitative survey (mean ± SD).

| During the first week |

By the end of the program |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How easy was RBT to understand? (1 = Difficult to understand, 5 = Easy to understand) |

4.59 ± 0.80 | 4.88 ± 0.33 | 0.125 |

| How easy was RBT to do? (1 = very difficult, 5 = very easy) |

3.06 ± 1.09 | 4.29 ± 0.99 | 0.001 |

| Program enjoyment (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much) |

2.82 ± 1.51 | 4.18 ± 1.13 | 0.002 |

| How helpful was RBT in improving overall quality of life? (1 = Very unhelpful, 5 = Very helpful) |

3.06 ± 0.97 | 4.18 ± 0.88 | 0.004 |

| Was the amount of time RBT took acceptable? (1 = Very unacceptable, 5 = Very acceptable) |

4.29 ± 1.10 | 4.71 ± 0.59 | 0.250 |

| Overall satisfaction (1 = Very dissatisfied, 5 = Very satisfied) |

3.94 ± 0.97 | 4.71 ± 0.47 | 0.014 |

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing RBT in CCRCs, as a part of typical practice in these facilities. Using the PARIHS framework (17), we were able to assess contextual factors such as leadership support, culture of change, evaluation capabilities, and receptivity to the RBT approach by obtaining perspectives from administrators and health leaders at the participating retirement communities and RBT participants. The semi-structured interviews administered to staff members with decision making authority regarding new programs provided useful information about the current culture of falls within retirement communities, and provided support for RBT as a falls-prevention program. Similarly, participants perceived observable health benefits after completing RBT, increased awareness toward tripping, and greater confidence with respect to mobility. In addition, administrators, staff, and participants identified potential barriers for implementation regarding the compatibility and customizability for different participant capabilities that would need to be considered before adopting RBT. RBT participant responses to the quantitative measure suggested that their perceptions of the intervention improved over the course of the 12-week program (i.e., by the end of the program they found it easier to do, they enjoyed the program more, and felt their quality of life improved).

Administrator responses clearly identified a loose culture of fall tracking at the facility level, and described evaluation capabilities for falls among residents as underdeveloped. This lack of systematic tracking of patient falls is a critical issue in that it would not allow for a clear observation of the effectiveness of RBT when implemented in practice. This is especially important in addressing the observability characteristic of an evidence-based approach that is necessary for adoption, confirmation of the utility of the intervention, and sustainability (31) within CRCCs. Many administrators reported difficulty in accurately tracking falls among their residents, whether fall-tracking technology was used or not. This also points to potential systems-change interventions that integrate systematic falls tracking, aggregation of information, and reporting out as a method of supporting and evaluating continuous quality improvement in these sites, for RBT or any other initiative focused on fall prevention (32). The desire for a more systematic way to track falls expressed by CRCC administrators suggests the addition of fall tracking may be feasible in CRCCs, which in turn would allow for proper evaluation of future fall-prevention programs.

When considering the evidence construct within the PARIHS framework (17), interviews and participant surveys indicated that administrators and residents positively viewed RBT. As has been noted in other dissemination and implementation research, published evidence and guidelines were viewed positively, but were not the driving factor relative to decision making for adoption, implementation, and sustainability (33). Indeed, the pull for RBT in these CRCCs was based more on the clinical experiences and perceptions of the staff. That is, administrators stated the need for a falls-prevention program regardless of whether falls are accurately captured in their respective retirement communities. Administrator interviews revealed that RBT would be viewed successful if resident balance, health and/or safety were improved—underscoring the focus on locally relevant information rather than systematically gathered data on current or historic fall rates in CCRC residents. In contrast, administrator interviews highlighted that providing evidence of short and long-term effectiveness as well as program generalizability would be important components when considering if RBT should be a sustained offering at CCRCs. While these differences in the expressed need for data may seem to conflict, it is consistent with other literature that indicates organizational decision making is based on a blend of tacit knowledge of the institutional context and a gap in understanding of the longer-term effectiveness of a novel intervention (33). As such, an administrator that interacts with residents on a daily basis does not consider data necessary to make the case for a falls prevention program because it appears clear that it would benefit patients. However, RBT is a novel innovation for falls prevention that has not been observed at scale by administrators, and as such, they require systematic longer-term data to facilitate decision-making.

An anticipated barrier was identified relative to the cost of the equipment, amount of training needed for staff members to use RBT equipment and to ensure safety, and the optimal RBT protocol. These issues were summarized in the need for RBT facilitation in CRCCs to increase the likelihood of adoption. Providing adequate cost information regarding RBT cost-benefit may overcome barriers identified relative to the start-up and training costs associated with RBT. However, it will be important to ensure that the benefit perspective is considered from multiple levels—residents (e.g., benefits in sustained independent and improved quality of life), CCRCs (e.g., benefits related to retaining and recruiting new residents based on the available programming), and insurers (e.g., benefits to reduced claim costs due to falls). When considering medical costs for falls (e.g., costs exceeded $50 billion in 2015 (2)) and that cost-benefit information is typically required to make a case for insurance coverage decisions, highlights the need for a cost-benefit analysis as a priority area for future RBT studies. The lack of information in this area influences the CRCCs perceptions of the evidence underlying RBT, and may reduce the likely adoption of RBT prior to demonstrating cost-effectiveness (17).

The compatibility of RBT within the CRCC setting and resident lifestyle patterns emerged as an area for future research implementing similar programs into practice. Beginning with the reach of the intervention, 74 residents were excluded based on physical or cognitive limitations. This suggests the RBT approach is incompatible with CRCCs with residents that are more dependent. Indeed, due to the exploratory nature of this study, extra care was taken to include residents who were more likely to tolerate the RBT protocol and have less likelihood for injury (i.e. residents without clinical osteoporosis). Other compatibility issues derived from the resident interviews included the competition with other activities on site. As part of a larger, more comprehensive future study, exploration of ways to customize RBT to allow residents with a broader range of physical and cognitive limitations should be considered.

Facilitation of RBT in retirement communities could be administered by both staff and residents (34). Administrator interviews demonstrated that key leaders among retirement communities would be supportive of falls-prevention programs aimed at improving resident health and safety. Administrator interviews suggested that a local facilitator may be needed to move the intervention into sustained practice. Residents suggested that demonstrating the effectiveness of the program and using participant testimonials to make the effects observable could facilitate greater resident engagement. Furthermore, encouraging past RBT participants to share their experiences with their peers could be an impactful method to increase future RBT participation in retirement communities and increase social interaction among residents. This engagement was also tied to potential for sustainability in the administrator interviews—a large group of residents would need to participate for the intervention to be sustained.

This study was limited by the preliminary nature of the work. Specifically, the small number of sites, large number of exclusion criteria, and small sample of residents limits the generalizability of the work to CCRCs and RBT participants dissimilar to those investigated here. However, focusing on potential contextual evidence and facilitation factors, concurrently with preliminary effectiveness and feasibility testing, will allow for a speedier movement of RBT into practice should it be demonstrated as effective. Concurrently, this trial provided information to match future RBT design and marketing characteristics to implementation strategies that could lead to benefits for a large proportion of CRCC residents. In addition, our methods and analysis of the administrator interviews were guided by a multidimensional framework that represents the complexity of the process of implementing evidence-based practices (17). Additionally, we gathered feedback from both the adoption agent (administrators) and consumer (residents). Both RBT participants and administrator interviews provided useful information needed to evaluate the feasibility of RBT at retirement communities. Using the PARIHS framework, the context, evidence, and facilitation of RBT was considered.

Falls are a major concern among adults living in retirement communities. RBT offers a potent, on-site balance training exercise for improving the reactive response needed to recover from common balance perturbations such as a trip. Interviews with administrators and RBT participants support the need and potential success for RBT as a falls-prevention program within retirement communities. This pilot work also provides a number of areas for future research. At the resident level, follow-up trials that examine effectiveness in a larger independent-living CCRC population, application to individuals with a broader range of physical and/or cognitive limitations, and implementation with a lower technical and human supervision burden, would allow broader translation to the community. In addition, clarifying the time duration of RBT-induced improvements in fall prevention, and the dosage of RBT necessary to induce these improvements, would allow a more informed implementation. At the CRCC level, systems-based research is needed to allow for pragmatic approaches to reduce falls in these settings. The settings involved in this pilot may or may not be representative of the broader population of settings, but within the context of our trial, research focused on developing assessment and tracking systems for falls would greatly benefit research and practice. Finally, we examined setting context and facilitation and perceptions of the RBT innovation from the perspective of the PARIHS framework. Additional research that examine these issues quantitatively would allow scientists to better characterize the process by which fall prevention interventions, such as RBT, can be adopted, implemented, and sustained in CRCC settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 AG045723 to MLM).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to report. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and Fall Injuries Among Adults Aged >/=65 Years - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention CfDCa [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/fallcost.html.

- 3.Mansfield A, Peters AL, Liu BA, Maki BE. Effect of a perturbation-based balance training program on compensatory stepping and grasping reactions in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90(4):476–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen X, Mak MK. Technology-assisted balance and gait training reduces falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(2):103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitty E, Flores S. Fall prevention in assisted living: assessment and strategies. Geriatr Nurs. 2007;28(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taggart HM. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on balance, functional mobility, and fear of falling among older women. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(4):235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, Close JC, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(3–4):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aging NCo [Internet].

- 9.Rosenblatt NJ, Marone J, Grabiner MD. Preventing trip-related falls by community-dwelling adults: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1629–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai YC, Bhatt T, Yang F, Wang E. Perturbation training can reduce community-dwelling older adults’ annual fall risk: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(12):1586–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabiner MD, Bareither ML, Gatts S, Marone J, Troy KL. Task-specific training reduces trip-related fall risk in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(12):2410–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt T, Yang F, Pai YC. Learning to resist gait-slip falls: long-term retention in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(4):557–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aviles J, Allin LJ, Alexander NB, Van Mullekom J, Nussbaum MA, Madigan ML. Comparison of treadmill trip-like training versus Tai Chi to improve reactive balance among independent older adult residents of senior housing: a pilot controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(9):1497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansfield A, Wong JS, Bryce J, Knorr S, Patterson KK. Does perturbation-based balance training prevent falls? Systematic review and meta-analysis of preliminary randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):700–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owings TM, Pavol MJ, Grabiner MD. Mechanisms of failed recovery following postural perturbations on a motorized treadmill mimic those associated with an actual forward trip. Clinical Biomechanics. 2001;16(9):813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bieryla KA, Madigan ML, Nussbaum MA. Practicing recovery from a simulated trip improves recovery kinematics after an actual trip. Gait Posture. 2007;26(2):208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(4 Suppl):S45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estabrooks PA, Harden SM, Almeida FA et al. Using Integrated Research-Practice Partnerships to Move Evidence-Based Principles into Practice. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS Framework—A Framework for Guiding the Implementation of Evidence-based Practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2004;19(4):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhlig T, Fongen C, Steen E, Christie A, Odegard S. Exploring Tai Chi in rheumatoid arthritis: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh GY, Roberts DH, Wayne PM, Davis RB, Quilty MT, Phillips RS. Tai chi exercise for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. In. Respiratory Care2010, p 1475+. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F, Harmer P, Glasgow R et al. Translation of an effective tai chi intervention into a community-based falls-prevention program. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1195–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, Campbell MK. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2002;23(6):662–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations 5th ed: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estabrooks PA, Brownson RC, Pronk NP. Dissemination and Implementation Science for Public Health Professionals: An Overview and Call to Action. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, Hagedorn HJ. A Guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci. 2011;6:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How Can We Increase Translation of Research into Practice? Types of Evidence Needed. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28(1):413–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cairney P, Oliver K. Evidence-based policymaking is not like evidence-based medicine, so how far should you go to bridge the divide between evidence and policy? Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2016;11:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]