ABSTRACT

Background: It is often claimed that military veterans are reticent to seek help for mental disorders, even though delayed treatment may impair recovery and impact the wellbeing of those close to the veteran.

Objective: This paper aims to explore the barriers and facilitators to accessing professional mental health support for three groups of veterans who met criteria for a probable mental health disorder and: (1) do not recognize a probable mental disorder; (2) recognize they are affected by a mental disorder but are not seeking professional support; or (3) are currently seeking professional mental health support.

Method: Qualitative telephone interviews were conducted with 62 UK military veterans. Thematic analysis identified core themes along an illustrative journey towards professional mental health support.

Results: Distinct barriers and facilitators to care were discussed by each group of veterans depicting changes as veterans moved towards accessing professional mental health support. In contrast to much of the literature, stigma was not a commonly reported barrier to care; instead care-seeking decisions centred on a perceived need for treatment, waiting until a crisis event occurred. Whilst the recognition of treatment need represented a pivotal moment, our data identified numerous key steps which had to be surmounted prior to care-seeking.

Conclusion: As care-seeking decisions within this sample appeared to centre on a perceived need for treatment future efforts designed to encourage help-seeking in UK military veterans may be best spent targeting the early identification and management of mental health disorders to encourage veterans to seek support before reaching a crisis event.

KEYWORDS: Qualitative research, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, military psychiatry

HIGHLIGHTS

• Exploration of non-treatment seeking and treatment-seeking military veterans with mental health problems' barriers and facilitators to care.• Care-seeking decisions centred on a perceived need for treatment, typically waiting until a crisis event occurred.• Efforts to increase help-seeking should focus on early identification and management of mental health disorders to encourage help-seeking before reaching a crisis event.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Generalmente se sostiene que los veteranos militares son reticentes a buscar ayuda para trastornos mentales, incluso aunque el retraso del tratamiento puede afectar a la recuperación e impactar en el bienestar de las personas cercanas al veterano.

Objetivo: Este trabajo busca explorar las barreras y facilitadores al acceso a apoyo profesional de salud mental para tres grupos de veteranos que cumplen criterios para un probable trastorno de salud mental y: 1) No reconocen un probable trastorno mental; 2) Reconocen que están afectados por un trastorno mental pero no están buscando apoyo profesional; o 3) están actualmente buscando apoyo profesional de salud mental.

Método: Se realizaron entrevistas telefónicas cualitativas a 62 veteranos militares de Reino Unido. El análisis temático identificó temas nucleares a lo largo de un viaje ilustrativo hacia el apoyo profesional de salud mental.

Resultados: Se discutieron distintas barreras y facilitadores a la atención por cada grupo de veteranos, describiendo cambios a medida que los veteranos se movían hacia el acceso al apoyo profesional de salud mental. En contraste a mucha literatura, el estigma no fue una barrera a la atención comunmente reportada; en su lugar las decisiones de búsqueda de atención se centraron en la necesidad percibida de tratamiento, esperando hasta que ocurría un evento de crisis. A pesar de que el reconocimiento de la necesidad de tratamiento representó un momento decisivo, nuestros datos identificaron numerosos pasos clave que debían ser superados antes de la búsqueda de atención.

Conclusión: Dado que las decisiones de búsqueda de atención dentro de esta muestra parecían centrarse en una percepción de necesidad de tratamiento, los esfuerzos futuros diseñados para promover la búsqueda de ayuda en veteranos militares del Reino Unido podrían ser mejor invertidos apuntando a la identificación temprana y manejo de trastornos de salud mental para alentar a los veteranos a buscar apoyo antes de alcanzar un evento de crisis.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Investigación cualitativa, Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático, Trastornos Depresivos, Trastornos de Ansiedad, Psiquiatría Militar

Short abstract

背景: 通常认为,退伍军人不愿为精神障碍寻求帮助,即使延误治疗可能会影响康复并影响与退伍军人关系密切的人的健康。

目标: 本文旨在探究退伍军人获取专业精神健康支持的障碍和促进因素,这些退伍军人可分为以下符合可能的精神健康疾病标准的三组:1)不承认可能的精神疾病; 2)认识到他们患有精神疾病,但没有寻求专业支持;或3)目前正在寻求专业的心理健康支持。

方法: 对62名英国退伍军人进行了定性电话采访。主题分析在向专业心理健康支持的说明之旅中确定了核心主题。

结果: 每组退伍军人都通过描述向专业心理健康支持寻求帮助时发生的变化,讨论了护理方面的不同障碍和促进因素。与许多文献相反,羞耻感不是普遍报告的护理障碍。相反,寻求治疗的决定集中在直到危机事件发生才感知到的治疗需求。虽然对治疗需求的识别是关键时刻,我们的数据确定了在寻求护理之前必须克服的许多关键步骤。

关键词: 定性研究, 创伤后应激障碍, 抑郁症, 焦虑症, 军事精神病学

1. Background

Recent research suggests that approximately 7% of UK military veterans (defined as anyone who has served for 1 day or more in the UK Armed Forces (Ministry of Defence, 2017)) are likely to suffer with PTSD and around 22% report symptoms of a common mental disorder such as anxiety or depression (Stevelink et al., 2018). Mental disorders in veterans are associated with worse outcomes in terms of income and unemployment, with those who take longer to seek help among the worst affected (Iversen et al., 2005; Murphy, Palmer, & Busuttil, 2017). Furthermore, military veterans appear reluctant to seek formal mental health support; with more than half of those who self-report as experiencing symptoms of a mental health disorder not engaging with health-care professionals to discuss support options (Stevelink et al., 2019). Whilst the negative impacts of delaying mental health treatment, and the resistance to seeking formal mental health support, are not unique to the military veteran population they do illustrate the need for continued efforts to foster improved rates of help-seeking in this population.

The extensive research exploring barriers to care within active service and veteran populations has typically identified a number of key barriers to help-seeking including stigma, negative attitudes to health care, practical issues accessing help and a drive to self-manage symptoms (Coleman, Stevelink, Hatch, Denny, & Greenberg, 2017; Iversen et al., 2005, 2010, 2011; Huck, 2014; Sayer et al., 2009; Sharp et al., 2015; True et al., 2015). However, conflicting evidence exists regarding the relationship between these endorsed barriers and help-seeking behaviour. For example, a recent qualitative review (Coleman et al., 2017) deduced that increased levels of stigma act as a barrier to help-seeking, whereas a quantitative review (Sharp et al., 2015) found no significant association and a possible modest association between higher anticipated stigma and increased help-seeking. Such contradictory results may imply that different barriers and facilitators are important at different points on an individual’s journey towards professional mental health support (Goldberg & Huxley, 1980; Huck, 2014; Iversen, 2013; Jakupcak et al., 2013; Mellotte, Murphy, Rafferty, & Greenberg, 2017; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997; Sharp et al., 2015). Whilst it is understandable that much research has focused on help-seeking populations, due to the ease of access to this participant group, focusing on this group, at the expense of non-help seeking populations, introduces a bias to the conclusions that are drawn and may also account for the contradictory results seen in contemporary literature.

In a qualitative exploration of both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking (seeking treatment for PTSD) Vietnam and Afghanistan/Iraq veterans in the US Sayer et al. (2009) utilize the behavioural model of service use (Andersen & Newman, 1973) to explore help-seeking behaviour in terms of predisposing, enabling and need factors. Sayer et al. (2009) identified seven barrier themes (avoidance of trauma-related feelings and memories; values and priorities that conflict with treatment-seeking; treatment discouraging beliefs; health-care system concerns; knowledge barriers; access barriers; invalidating post-trauma socio-cultural environment) as well as four facilitator themes (recognition and acceptance or PTSD and availability of help; treatment-encouraging beliefs; system facilitation; social network facilitation and encouragement) which were present, although to varying degrees and with differing significance in both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking veterans.

Whilst all of the sample from Sayer et al. (2009) had submitted a claim to the Department for Veteran Affairs for military-related PTSD the current study expands the exploration of non-treatment seeking veterans by adding an additional group, those who report that they believe that they are not experiencing a mental health concern despite self-reporting symptoms of mental health distress.

This paper reports on qualitative in-depth interviews with UK military veterans at different time points on this journey to seeking professional mental health support. We explore the experiences of three distinct groups of veterans, all of whom reported symptoms indicative of probable mental disorder. The three groups include those who (1) did not recognize that they are affected by a probable mental disorder; (2) recognized they are affected by a probable mental health disorder but are not seeking professional mental health support; and (3) sought professional mental health support. Being able to recruit both help-seeking and non-help-seeking military veterans allows for the identification and comparison of pertinent barriers and facilitators to help-seeking across different points on an illustrative pathway to professional mental health support.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were males who had left the Armed Forces in the last 5 years identified from the King’s Centre for Military Health Research (KCMHR) health and well-being cohort study (Fear et al., 2010; Hotopf et al., 2006; Stevelink et al., 2018). A major strength of drawing on the KCHMR cohort study is that it is a randomly selected sample of all UK Armed Forces Personnel and veterans which includes both help seekers and non-help seekers. All KCMHR cohort study personnel filled in various measures to assess their mental health and were asked whether they had experienced any problems with their health in the last 3 years (including their mental health) and if so, whether they had sought help.

Those personnel whose scores on mental health measures exceeded routine cut off thresholds indicative of a mental disorder were identified and divided into the three groups outlined above. A common mental disorder (anxiety or depression) using a score of 11 or more on the 12 item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) (Goldberg et al., 1997); Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder using a score of 50 or more on the 17 Item National Centre for PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) (Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994); Alcohol misuse using a score of 16 or more on the 10 item World Health Organization Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001; Fear et al., 2007).

Group Two and Group Three reported that they were currently experiencing stress, emotional or mental distress whereas Group One did not self-report any mental health distress but were identified as probably experiencing a mental disorder based on their scores on the measures explained above.

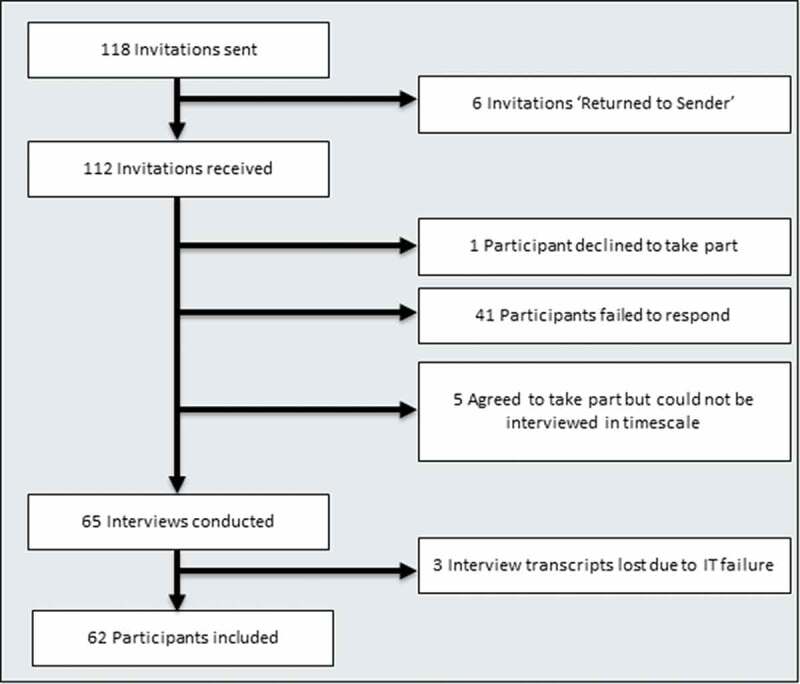

All potential participants had previously agreed to be contacted again for future research studies. Each participant was sent a postal pack asking them to contact the research team if they would like to take part in the study. Those participants who contacted the research team were given an opportunity to ask questions about the study and asked to return an informed consent form via post. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Fifty-five per cent of those approached agreed to take part. The participant recruitment procedure is shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment procedure.

Telephone interviews took place between May 2016 and December 2016 and lasted between 45 min and 1 h and 45 min (median (interquartile range) 1.07.25 (59–74 min)). At the beginning of the interview, all participants were reminded of their right to withdraw at any point or refuse to answer any question. Participants were told that they could withdraw from the study post-interview within the data collection period (they were given a specific date). A robust risk procedure was in place with experienced clinicians available to provide calls to participants who exhibited any signs of distress during the interview. Each participant also received an extensive ‘signposting booklet’ containing many sources of support, from emotional to financial, for military veterans.

Recruitment continued until data saturation had been achieved, past the point where no new barriers or facilitators were being identified within the data (Ando, Cousins, & Young, 2014; Saunders et al., 2018). Because three groups of participants were employed in the research a larger sample size was utilized in order to ensure that each group reached saturation and that differences between the groups could be illuminated. Again, saturation was determined when no new barriers or facilitators were identified within a group. Sixty-two telephone interviews were included in total, a more than sufficient size to reach data saturation (Ando et al., 2014; Ritchie, Lewis, McNaughton Nicholls, & Ormston, 2013).

2.2. Interview protocol

The semi-structured study interview protocol was derived from reviewing the contemporary military and general population literature on barriers and facilitators to seeking mental health support. Interviews covered topics focused on personnel’s military history; transition from the military; perceptions of mental health and mental health treatment; personal history of mental health; and barriers and facilitators to mental health support. For participants in Group Three, questions focused on asking them to outline their journey to mental health support, recalling their treatment pathway and how they went about seeking help. Questions for participants in Group Two centred on asking them to recall their recognition of mental health distress and the reasons that prevented them from seeking help. For those participants in Group One, questions focused on asking them to talk about their perceptions of their own mental health.

The interview protocol was piloted on three mental health researchers with a background in psychology/psychiatry as well as three military veterans. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (PNM) Research Ethics Subcommittee (RESC) at King’s College London (Ref: PNM RESC HR-15/16-2125).

2.3. Analysis

All telephone interviews were conducted by LR, audio-recorded and transcribed in full by a professional transcription service. LR had prolonged engagement with the data through conducting each interview and reading each transcript before beginning the analysis. All participants were provided with pseudonyms as used in the Results section. The interview transcripts were then analysed according to the principles of the Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) facilitated using NVIVO software (NVivo, 2012). Detailed notes around each stage of the analysis were kept explaining decisions that were made and documenting the development of themes. This analysis involved inductively identifying patterns and themes within the data, in a bottom-up manner, thus developing a new theory from progressively more abstract summaries of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The analysis began with a thorough reading of each interview transcript, developing draft codes for all chunks of the script and ensuring that each ‘utterance’ was assigned a code. All generated codes were examined to identify ways in which codes may be combined or ways in which they could fit together to form an overarching theme. A series of diagrams were created to explore thematic connections. Data were not ‘fitted’ into existing themes, rather themes were developed anew for each pattern identified. Themes were explored for both internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity to ensure that there was a common thread between all sub-themes, and that each theme was distinct from the other, and were developed into hierarchies. This process took place for each interview transcript before merging the coding categories across interview transcripts and creating a final coding hierarchy and overarching thematic map. Once coding had been completed and a thematic map was developed a coding scheme was created and each transcript was re-read in relation to this coding scheme to test for referential adequacy. It is important to note that this is a recursive, not linear process which involves constant comparison back to the data. Regular peer debrieifing meetings were held within the research team (LR, SAMS, NG) to explore the process being undertaken and discuss the developing themes and overarching framework. Those themes which were discussed by over 75% of veterans in each group are labelled as ‘major’ themes. Whilst the frequency of occurrence of themes does not equate to a measure of importance, it is able to represent a sense of how common a response was across participants (Toerien & Wilkinson, 2004).

3. Results

3.1. Mental health characteristics

The demographic and mental health characteristics of those who took part in the study are summarized below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

|

Age (years) |

n (%) |

|

||

| <30 | 5 (8%) | |||

| 30–39 | 9 (14%) | |||

| 40–49 | 28 (44%) | |||

| >50 | 21 (33%) | |||

| Service | ||||

| Naval Services | 10 (16%) | |||

| Army | 40 (63%) | |||

| Royal Air Force | 13 (21%) | |||

| Rank | ||||

| Officer | 15 (24%) | |||

| Other Ranks | 48 (76%) | |||

| Engagement Type | ||||

| Regular | 47 (75%) | |||

| Reserve |

16 (25%) |

|

||

|

Mental Health Caseness |

Overall |

Group One (n = 31) |

Group Two (n = 10) |

Group Three (n = 21) |

| GHQ: Common mental disorders | 61 (98%) | 31 (100%) | 9 (90%) | 21 (100%) |

| PCL: Probable PTSD | 16 (25%) | 5 (16%) | 2 (20%) | 9 (43%) |

Initial group designation placed veterans relatively evenly across the three groups (i.e. close to 20 in each). However, after conducting the interviews with veterans some reallocation of grouping was required. The remapping exercise occurred for two reasons. Firstly, because help-seeking behaviour is not a static state some veterans changed groups from the time, the initial measures were taken in the cohort study data collection, for example they decided to seek help for a mental health problem and therefore moved from Group Two to Group Three. The second reason that the remapping exercise occurred was that the qualitative interviews enabled a more granular discussion around help-seeking behaviour and recognition of mental health distress than was possible in the cohort study questionnaire data collection method. The initial measure of group membership was sufficient to identify those veterans who may be eligible to take part in the research, the interview itself was employed as a confirmation of group membership providing a time appropriate validation of group membership.

The demographic characteristics of the participants who took part in this research mapped sufficiently to the Biannual Diversity data for males who left the UK Armed Forces in the 5-year period between 2012 and 2016 (data not shown) [27] in terms of service (Army, Navy, RAF), age bracket, reserve or regular status and rank (officer or not). Table 2 represents the quantitative measures of common mental disorders (GHQ12) and PTSD (PCL) for each of the three participant groups.

Table 2.

Mental health characteristics for each participant group.

| N | Mean | S.D. | Median | IQR1 | IQR3 | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ Score | ||||||||

| Group One | 31 | 16.9 | 5.4 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 10 | 30 |

| Group Two | 10 | 21 | 9.8 | 19 | 13 | 33 | 9 | 36 |

| Group Three | 21 | 20 | 7.4 | 17 | 15 | 25 | 11 | 33 |

| PCL Score | ||||||||

| Group One | 31 | 31.5 | 13.7 | 27 | 21 | 42 | 17 | 62 |

| Group Two | 10 | 28.5 | 15.8 | 34.5 | 24 | 44 | 23 | 66 |

| Group Three | 21 | 46.9 | 17.9 | 44 | 34 | 57 | 21 | 78 |

For common mental disorder (measured via the GHQ12) there are a number of differences between the three groups of participants that suggest that symptom severity increases depending on group membership. The results suggest that Group One may have milder symptoms and that Group Two may in fact have the most severe symptoms, perhaps in light of Group Three receiving treatment which has reduced their symptom severity. However, it is important to note that these differences are not statistically significant and that Group One scores are still clinically significant therefore these participants would still benefit from some form of professional assessment and potential treatment.

For PTSD (measured via the PCL) again symptom severity appears to be associated with group membership. An analysis of variance showed that there was a significant difference in the PCL scores between the groups, F (2,59) = 6.17, p = 0.0037. Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction for significance (in order to identify the specific difference between the groups which was significant) indicated that the PCL scores were significantly higher in Group Three (M = 46.86, SD = 17.87) than in Group One (M = 31.45, SD = 13.68), p = 0.003. This suggests that those with higher PTSD scores are more aware and more likely to be in treatment.

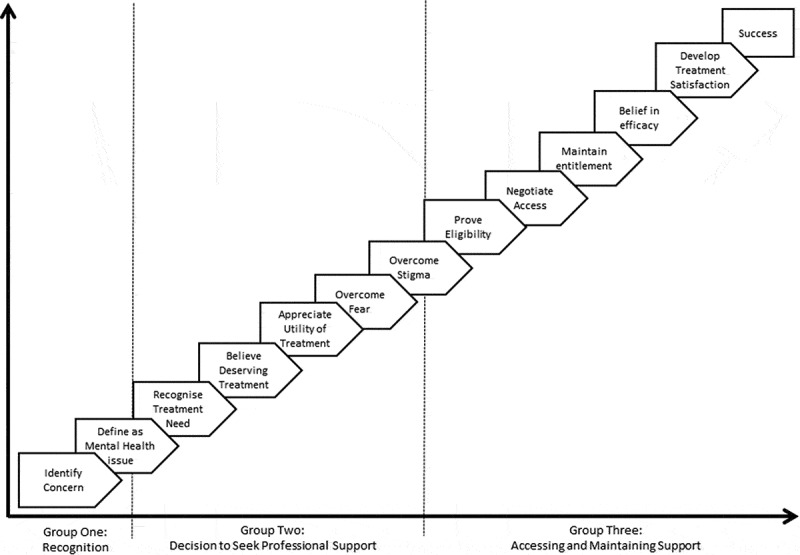

3.2. Journey to processional mental health support

Following the methodology of Thematic Analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006), the analysis of the barriers and facilitators enabled us to develop a model of an illustrative ‘journey to professional mental health support’ with potential barriers and facilitators annotated to this model. In line with the aims of Thematic Analysis, the model represents a thematic map of the data which tells a story about how the themes fit together and provide a complex model of the themes (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006). The three key stages of the journey represent the participant groupings as outlined in the Method section. These groupings are based on participants' responses to two key decision points. Firstly, whether or not they believe that they have a mental disorder and secondly whether or not they are currently seeking professional support for that mental disorder. This results section will explore these themes within each of these groups and compare them to one another. The journey developed from this indicates that different barriers and facilitators were more pertinent across these three participant groups. Our data did not suggest that all veterans followed the same path towards care but supported that the steps described below are relevant for many, although not necessarily in a linear fashion.

3.3. Stage 1: recognition

The first stage on the journey involves veterans recognizing that they may be suffering with a mental disorder. Navigating this stage requires both being able to identify that a problem exists and defining the problem as a mental disorder. Group One veterans failed to identify any symptoms of mental distress, believing that they did not have a mental disorder. Where such symptoms were recognized, they were not defined as ‘mental health’ but were seen as part of the normal ups and downs of life.

I mean I have down days, I have up days but nothing … I’d say beyond the spectrum of normality or acceptability (Matthew: Group One)

Some veterans did not consider that they had the knowledge or understanding to confidently label their distress as being mental health related. Others stated that the lack of perceived severity, or their ability to self-manage symptoms, meant that they were not a mental disorder.

I know sort of things have affected me to some degree. But (umm) I wouldn’t say that they’re in anyway (umm) severe or even, I don’t know, not even moderate (Richard: Group One)

The define theme represents a ‘major’ barrier which was discussed by over 75% of veterans in Group One.

Those veterans able to identify and define a mental disorder (those in Group Two and Three) described symptom recognition as prompting them to make this distinction. Problems with sleep, isolation and anger seemed to be particularly recognized.

Because I… I don’t sleep(umm) … I’d wake up in the wee hours and I’d stay awake for two or three hours (Gary: Group Two)

The identify theme represents a ‘major’ facilitator which was discussed by over 75% of veterans in Group Two and Three.

Veterans also mentioned that when they were no longer able to self-manage symptoms, they then defined their distress as a mental disorder, either through experiencing suicidal ideation or an incident where they felt that their actions placed another in danger.

I did actually take an overdose at one stage (umm) and I think that was probably my wakeup call (umm) taking the overdose (Michael: Group Three)

Sometimes another’s intervention or expression of concern were required to reach this point. This could be a significant other, wife or girlfriend, co-workers and physical health or medical professionals.

I was talking to my wife I think, because she said that I had … I had massive issues (Ken: Group Three)

3.4. Stage 2: decision to seek professional support

The second stage of the journey to mental health treatment focused on the decision to reach out for professional support. Veterans in Group Two, although able to recognize that they had a mental health concern, did not see their symptoms as severe enough to warrant treatment. In particular references to maintaining typical daily activities such as work which prevented them from recognizing a need for treatment.

Well I’m sort of functioning. I mean I’m holding a job down and … and doing the usual things, I’ve sort of convinced myself there that everything was fine (John: Group Two)

The need for treatment theme represents a ‘major’ barrier which was discussed by over 75% of veterans in GroupTwo and Three.

Veterans also spoke of not deserving care, stemming from the military ethos of being self-reliant and not burdening anyone else with their individual problems.

That idea of self-reliance, not saying that you don’t seek help, or you rely on other people, but you at least attempt to look after yourself. You take personal responsibility for your actions, you don’t expect a hand-out (Ron: Group Two)

Additionally, many described symptoms not severe enough to deserve treatment in comparison to others’ symptom severity;

There’s guys with real issues and you know there’s people with real issues that need … I just don’t really feel like it’s big enough an issue for me to actually go and do that (James: Group Two)

Negative attitudes were expressed regarding the utility of treatment, particularly fearing that a therapist would not understand them or that it would be impossible to build a trusting relationship with a stranger. Additionally, respondents expressed a reluctance to take medication which was felt to be a common clinician action and which they saw as only serving to cover up the problem rather than resolve it.

You meet someone for the first time (umm) and you feel awkward because you’ve never met them, you’ve got to try and know them. They’ve got to try and get your trust to open up (Charles: Group Two)

Veterans described being fearful of being vulnerable which was related to wanting to ‘keep the box closed’.

Concerns around stigma were also discussed, the associated perceptions around weakness or the label of mental health calling to mind an image of a ‘crazy person’. Veterans also feared being viewed as ‘fakers’ or ‘malingerers’ and not being believed by those around them. Each stigmatizing belief was coupled with concerns about the potential impact of admitting a mental health disorder could have on their military or civilian career.

You don’t let people see your weaknesses. If you’ve got flu, people just go ‘Oh he’s ill, he’s got flu!’ But if you go ‘I don’t feel too right in my head’, the stigma around it is ‘Oh there’s nothing wrong with you, you’re just blagging it!’ (Charles: Group Two)

Group Three veterans described a number of key factors as facilitating their progress along the journey to professional mental health support. Recognizing a need to seek professional support was discussed as closely tied to veterans recognizing that they had a mental health disorder which they could not self-manage. As mentioned earlier this was in the context of a crisis event such as a suicide attempt or where their actions placed another at risk. Thus, our data suggested that recognizing a need to seek treatment required veterans to reach a crisis point which appeared to force veterans to leap-frog the Recognition phase into the Decision to Seek Professional Support phase.

Well I was at crisis point when I went to see the GP (umm). So you know there wasn’t even an option not to (Christopher: Group Three)

In addition to this, previous treatment experiences played a role in mitigating negative perceptions around the utility of treatment for some veterans.

It was a lot easier to reach out because I already knew that reaching out would help (Ryan: Group Three)

Veterans also mentioned help-seeking facilitators around stigma such as seeing others seek help or recent anti-stigma campaigns which helped them decide to seek help.

Leaflets … with campaigns … pushed out from … different departments in the … the medical world … And also education of the bosses, the chain of command, … you know to push down the message that actually it’s ok to discuss this issues and it’s ok to have them (Christopher: Group Three)

3.5. Stage 3: accessing and maintaining mental health support

Once veterans had decided to seek professional mental health support, various barriers were evident. These included concerns around eligibility including worries that others would tell them that there was nothing wrong and that they should ‘man-up’, as well as prior negative help-seeking experiences involving being told that they were not eligible.

A letter come through from IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) service saying we can’t treat you because you’ve got more than one underlying issue. … to be honest it was a smack in the face because I like all I want is a bit of help and no one’s willing to help me (Robert: Group Three)

Veterans also discussed long waiting lists in the NHS as hindering access to professional support and resulting in the perception that there was no professional support available or at least not at a time when it was needed.

In Civilian Street I’m struggling loads just to try and get to see someone (Robert: Group Three)

Communication issues also prevented access to services. These included veterans becoming lost in the system or no-one getting back in touch with them regarding requests for professional support. Problems with appointments interfering with work schedules and a lack of professional support in local areas were also cited in relation to access.

Difficulties proving their ongoing entitlement to help were also discussed. One veteran who wanted professional support reported being told by medical professionals that they no longer needed care. Another had their care stopped at the point of transition. Once registered with a GP, they had to wait months for an NHS referral, with no interim professional support.

I was anxious because I knew I wasn’t right properly. But I was obviously listening to the professional. I have to take on board what they say don’t I? (Steven: Group Three)

Many veterans ceased treatment because of concerns around the efficacy of the care they had received. Typical beliefs were that military mental health care focused on placing a veteran in a box and failed to deal with the root cause of issues, acting instead as just a temporary fix.

I felt it was scripted and you know they were just … there was nothing personal about it because they were just “how are you feeling?”, you know and ticking boxes. It wasn’t getting to the root of my problems, it was more like just a standard (Robert: Group Three)

Veterans engaged in mental health treatment failed to discuss particular elements that allowed them to become eligible or entitled to care. Rather they discussed their pathway to care, and which agencies had enabled them to access professional mental health support. One route to care discussed involved a veteran either going to a Medical Officer (MO) whilst still serving or to a GP, depending upon whether their mental health disorder began whilst they were still in Service, and whether they got a referral. These options were the first port of call, with veterans accessing services, such as Combat Stress (a veteran’s mental health charity), often under the direction of their GP, in order to side-step the long waiting times for NHS services. A number of veterans had contacted Combat Stress directly under guidance from friends or via a representative at the Royal British Legion (a charity supporting those who have/are serving in the Armed Forces and their families). A small number of veterans accessed private medical care and this was to ensure a perceived higher standard of care or again in order to avoid long NHS waiting times.

Positive beliefs about the efficacy of treatment helped veterans to remain in treatment. These centred on veterans being given an understandable diagnosis that helped them get to grips with their problem and treatment. These individuals had already identified a concern and defined this as related to mental health, the psycho-education they were receiving was focused on understanding the utility of treatment and fostering a belief that they could get better.

It was very good because it educated me as to what the … you know what the condition was, … how you can overcome some of the symptoms, really the main thing was getting a label I’m now beginning to understand (Jason: Group Three)

Veterans also spoke about a preference for treatments where they could see a tangible practical benefit such as sleep therapy or coping techniques that worked almost instantly.

The grounding stuff … they’ve taught me … when like I have nightmares and stuff like that … and I feel all overwrought with anxiety and stuff like that, I still use their … the techniques they taught me (Steven, Group Three)

Veterans described experiencing positive reactions from colleagues and friends, and seeing others receive mental health care, as positively impacting on satisfaction with their treatment experience and again helping them to remain in treatment.

One of my one of my mates …, he came in and he was … he was going through the same counselling … The last person you expect to see. A very strong man. Somebody I’d certainly looked up to and I thought crikey it happened to him … if he’s here you know I’m normal (Paul: Group Three)

Veterans also believed that there had been a dramatic increase in rates of mental disorders, particularly after recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the so-called ‘tidal wave’, ‘time bomb’ or ‘tsunami’. This helped to normalize mental illness, although this belief in the dramatic increase of mental health disorders is not grounded in fact (Stevelink et al., 2019).

[the first Gulf War]. It wasn’t really accepted. You know people were sort of shunned because of it, but now … but since 2003 because we’ve been constantly you know in the fight shall we say, it’s become more prevalent/…. you know people are seeing it in more people. So because it’s becoming you know more noticeable, you can actually see that it is a real thing … (Daniel, Group Three)

4. Discussion

4.1. Journey to professional mental health support

Whilst the help-seeking behaviours of veterans with mental health problems have been studied extensively, prior research had not directly explored the lived experiences of UK military veterans at different points on their journey towards accessing professional mental health support since. Additionally, with the notable exception of Sayer et al. (2009) previous research had rarely been based on samples that include both help-seeking and non-help-seeking veterans. The results of the current study support a model of the core stages of a veteran’s ‘journey to professional mental health support’ identifying salient barriers and facilitators at each stage.

Previous work by Jakupcak et al. (2013) and Iversen (2013) has explored the utility of generic models, such as the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) and Goldberg and Huxley’s (1980) model, in describing this journey to professional mental health support. These journeys typically move from self-recognition, through planning to seek support, to attending and maintaining support. Two small-scale qualitative studies have recently developed specific journeys drawn from interviews with treatment-seeking veterans in the UK. Utilizing the retrospective recall of veterans with PTSD engaged in professional mental health support Mellotte et al. (2017) classified two distinct phases on the journey to professional mental health support: the initial decision to seek care; followed by navigation through treatment. Employing a similar population Huck (2014) depicted a journey to care beginning with acknowledgement and recognition, moving onto initial help-seeking and ending with treatment. Both these pathways appear to map onto the core principles of the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) and Goldberg and Huxley’s (1980) model.

Within our model, the phases along the journey are based on distinct decision points, or ‘game changer’ moments. These points allow us to clearly categorize the veterans into membership of one of the phases. A veteran either accepts that they have a mental health difficulty (Group Two/Three) or does not (Group One), he is either seeking treatment (Group Three) or is not (Group Two).

Our research model builds upon previous theoretical assumptions by developing a framework from research evidence drawn from veterans at different stages on the road to professional mental health support. In-depth interviews allowed for the identification of further granularity of the factors that were currently affecting veterans, developing an overarching framework which can be annotated with specific care experiences, as opposed to a list of barriers and facilitators. This work builds on the work of Huck (2014) and Mellotte et al. (2017) as it was able to speak to veterans currently at each of the three time points, thereby expanding the detail of the first two phases of the journey. This work also builds on the work of Sayer et al. (2009) in the US which looked at treatment seeking and non-treatment seeking veterans, by talking to veterans who did not explicitly state that they were experiencing a mental health concern. In addition to this, our veteran sample was not drawn from clinical samples from specific treatment centres and therefore covered a greater breadth of engagement issues and efficacy factors in the third phase of the journey.

4.2. Barriers and facilitators across groups

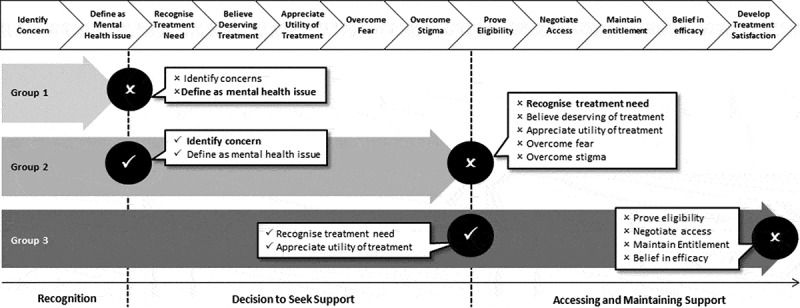

Figure 2 provides a summary of the core barriers blocking each group from progressing forward on their journey to professional mental health support as well as the key facilitators enabling a groups progression on to the next stage. Not all barriers were discussed equally by participants. Those barriers or facilitators in bold represent those that were discussed by a majority of veterans (over 75%) represent major themes as outlined in the analysis section and are highlighted in bold in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Journey to professional mental health support.

Figure 3.

Barriers and facilitators impacting each participant group.

The relationships between barriers and facilitators of help-seeking behaviour have been unclear. For example, whilst previous literature frequently cites stigma as being a major barrier to seeking help; contemporary reviews portray contradictory conclusions on this topic (Coleman et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2015). Our findings indicate that although some veterans do discuss the potential impact of stigma, help-seeking decisions were typically centred on the perceived need for treatment. Veterans who do not perceive a need for treatment fail to seek help, and only do so once a need for treatment is solidified; usually via others’ intervention or after a crisis event. Previous research based on retrospective recall from veterans engaged in mental health treatment supports the importance of both minimizing of symptoms (Sharp et al., 2015) and a lack of insight/readiness to change (Mellotte et al., 2017) as core barriers blocking engagement with professional mental health support. Treatment discouraging beliefs highlighted in the work of Sayer et al. (2009) in the US such as ‘treatment is just for those who are weak, crazy, or incompetent’ and ‘treatment is only for extreme problems’ support the notion that veterans struggle to perceive a need for mental health treatment until they reach these crisis events.

The ability to identify mental health distress was a common facilitator to engaging in successful mental health treatment in our sample. Although not reported as such a pivotal step, the importance of crisis events 'critical incidents in Huck (2014) and risk of not seeking help in Mellotte et al. (2017) and interactions from significant others in helping veterans to identify mental health distress has been highlighted in previous, retrospective analysis of help-seeking behaviour in military veterans’ (Huck, 2014; Mellotte et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2015). Sayer et al. (2009) in the US highlight recognizing and accepting a problem as a critical first step, a step which can be facilitated and encouraged by the veterans’ social network.

Our results suggest that despite a complex array of barriers and facilitators, the ability to monitor and evaluate ones’ own mental health, and subsequently identify mental health distress, may be important precursors to effectively engaging with mental health support.

4.3. Recognition of mental health distress

Whilst the current research highlights problems with the recognition of mental health distress, it is important to clarify that not all veterans with a probable mental disorder are unaware of this fact. The latest Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, a survey exploring the prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the English general population (over the age of 16), found that 82% of people who were identified as having a common mental disorder (through the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R)) perceived themselves as having a common mental disorder (McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins, & Brugha, 2016). Further research is needed to explore the recognition rates within the military veteran population. Although the inability to recognize a probable mental disorder may not be present in the majority of military veterans it is nevertheless important since most research focuses on treatment-seeking veterans (Group Three), and most interventions focus on reducing the stigma around seeking mental health support focused at those veterans in Group Two. It is important for both research, and interventions, to target this not insignificant group of people who do not recognize that they may be dealing with a mental health disorder.

4.4. PTSD and treatment need recognition

A finding from this research was the significantly greater degree of PTSD symptom severity found in Group Three participants compared to Group One participants. This suggests that perhaps PTSD symptom severity is equated with an increased level of recognition of treatment need and support seeking since Group Three participants were engaged in mental health treatment. However, given the small sample size employed in this qualitative piece of work additional research is needed to explore this further.

4.5. Implications

This research has identified several key levers for potential interventions to improve help-seeking for mental disorders within the UK military veteran population.

For those at the beginning of their journey, barriers to care appear to centre on difficulties in identifying symptoms of psychological distress and defining these as indicative of a mental disorder. This finding implies that interventions focused on helping veterans to monitor and manage their mental health might help them traverse this stage. The results indicate that veterans want to be self-reliant and take personal responsibility for their mental health and so tools should be developed that support this. It may be that service leavers could be provided with such tools, which would need to be evaluated, as they leave the protective umbrella of military life.

The results also highlight the importance of family, friends and significant others in facilitating veterans to recognize a mental disorder and choosing to seek help for that disorder. As such resources that support and empower family, friends and significant others in providing this support should be developed. One existing solution that may hold salience for the wider military family is Community Reinforcement and Family Training (CRAFT) (Smith & Meyers, 2004). CRAFT is an intervention to educate concerned significant others of those with potential substance abuse or mental health problems on how best to encourage that person to seek mental health support, as well as to monitor and improve their own well-being. Versions of CRAFT developed for military veteran populations are currently being developed and trialled in both the US (Erbes et al., 2015) and the UK (Archer, Rafferty, Harwood, Stevelink, & Greenberg, 2019).

Once veterans have identified that they may be unwell, they need to understand when the distress they are experiencing warrants mental health support. Tools are needed which will guide veterans to seek support before they reach a crisis point. Tools that support veterans in identifying the functional impact their psychological distress can have on different aspects of their lives should be developed. Such tools would aid veterans in identifying the degree of impact, recognize where improvements could be made, and also help them to track their progress during treatment.

Educating veterans on the success of mental health treatments and the positive improvements treatment can have on their quality of life may help to dispel negative treatment beliefs. Much work is already being undertaken in this area, for example CONTACT have successfully engaged many high-profile people to talk about the difficulties that they have experienced and their recovery process. A review of stigma by Rusch, Angermeyer, and Corrigan (2005) provides a summary of the many studies that provide empirical evidence asserting that such contact with mentally ill people can reduce stigma, a notion that is echoed in Greene-Shortridge, Britt, and Castro (2007) review of stigma in the military.

As care-seeking decisions within this sample appeared to centre on a perceived need for treatment, future efforts designed to encourage help-seeking in UK military veterans may be best spent targeting the early management of mental health disorders to encourage veterans to seek support before reaching a crisis event.

For veterans at the final stage of the path to professional mental health support, potential implications are focused on service providers. Whilst, there are numerous initiatives which aim to overcome access barriers, such as the Veterans Gateway (a website providing a single point of contact for Veterans seeking support) and the Veterans’ Mental Health Transition, Intervention and Liaison (TIL) (a specialist service offered by the NHS to support veterans), the impact of these initiatives is yet to be proven.

Changes to the way in which we provide support services to veterans may help to improve their opinion of these services, a key feature of future help-seeking as well as treatment satisfaction. In particular, veterans’ reticence to take medication and perceptions around the struggle to build a therapeutic relationship with a therapist were highlighted within this research. Clinicians may want to emphasize discussions around the utility of medication and the process of building a therapeutic relationship in initial sessions, as well as establishing realistic expectations from the therapy to prevent any disappointment or concerns over the utility of the treatment. Veterans were particularly positive about aspects of treatment that resulted in practical improvements such as coping techniques that work instantly. The assessment of functional impact mentioned earlier may also help to structure progress reviews to support veterans in recognizing the utility of treatment. Clinicians may also want to pay attention to the military drive to be self-reliant and provide veterans with resources that enable them to be a part of their own recovery.

4.6. Strengths and limitations

This research is based only on those who chose to respond to KCMHR health and well-being cohort study. Recruiting participants from this particular population ensured that we were able to identify those veterans with a probable mental disorder at one of the three distinct phases on their journey to professional mental health support. However, there is no way to know how this potentially skewed the results.

Participants were selected based on whether their scores exceeded thresholds indicative of a probable mental disorder on self-report measures. Although these have high levels of reliability, scores on these measures do not equate to a clinical diagnosis. Due to these selection criteria, it is also important to note that the prevalence of mental disorders in this research is not generalizable to the veteran population as a whole.

The study is limited in that it only uses male participants. This decision was made due to the low numbers of females in the Armed Forces, approximately 10% (10.2%) according to the 2016 MoD Biannual Diversity Statistics (statistics released by the MoD that report on the characteristics of those who have the left Armed Forces in the last 5 years) (Ministry of Defence, 2016). Unfortunately, ethnicity data were not collected on participants within this research. Future research should focus on female veteran’s journey to mental health support as well as exploring the ethnicity of veterans.

Due to the qualitative nature of this research, this study enabled veterans to voice aspects of their lived experience that they felt were important. As opposed to quantitative measures where veterans rate categories deemed important by others, in this research, the topics of discussion were more likely to be led by the veterans themselves. All qualitative research is subject to influences and it is important to acknowledge these influences. Within this research, the definition of the three participant groups and the subsequent sampling utilized placed an emphasis on the ‘definition’ of mental health distress and the ‘decision to seek support’ and may have influenced the authors’ interpretation of the findings. The interview questions differed for each group, for example Group One participants could not be asked about their experience of mental health support and therefore questions for this group focused on beliefs about mental health and treatment as opposed to direct lived experiences. It is important that the reader takes into account these influences throughout the manuscript. Future work should focus on analysing individuals' experiences longitudinally over time, without the need for such sampling classifications, in order to provide evidence to support the importance of these particular phases.

The MoD Biannual Diversity Statistics were utilized in the recruitment phase of this research to ensure that the research includes views from the major sub-groups in the UK Armed Forces. This is with the exception of female members of the UK Armed Forces, as discussed above (Ministry of Defence, 2016).

This research supports those broad categories of barriers and facilitators identified in earlier research, but extends upon this by providing greater detail, indicating the relationship that these factors have upon help-seeking behaviour, as well as the way in which their salience changes as a veteran progresses’ through the ‘journey to professional mental health support.’

4.7. Further research

This study suggests that interventions which provide military veterans with tools to understand, monitor and manage their own mental health, alongside appropriate guidance to mental health support, may prove successful in helping veterans counter the dominant barriers to seeking mental health support. Future research should focus on working closely with veterans and service providers to develop such a resource.

Research should also be conducted to explore the impact of past experiences with mental healthcare and mental health treatment on this pathway to care. In particular, veterans mentioned that previous positive experiences of professional mental health support helped to alleviate concerns around stigma and negative treatment perceptions.

The results of this research support qualitative work conducted in the U.S. by True et al. (2015) and Sayer et al. (2009) exploring barriers to care in US military veterans with PTSD. Both researchers support the importance of barriers centred on the drive for self-reliance prized in military culture as well as a myriad of access barriers to navigate when seeking mental health care. Sayer et al. (2009) also stress the significance of facilitators such as identifying a problem, believing that treatment will help, the facilitating role of friends and family as well as the positive impacts of anti-stigma campaigns. However, in light of the numerous cultural and health-care provision differences between the US and the UK, as well as significant differences in combat exposure and sociodemographic characteristics of the two militaries (Sundin et al., 2014), further research is needed to explore whether the working model we present would apply to veterans from the U.S. and other nations.

5. Conclusion

Being unable to identify a mental health disorder, or recognize a need for treatment, represents a common barrier to seeking mental health support. Within this sample, veterans appear to only seek professional mental health support when the severity of their symptoms takes this decision out of their hands. Future research must focus on aiding veterans to detect potential mental health disorders at earlier, potentially less severe stages, and encourage them to seek appropriate support (both professional and non-professional), to improve their quality of life and enable a more positive treatment prognosis. Providers of veterans’ mental health support should take note of the many other factors which may also play a role in this decision-making process.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the participants who agreed to take part in this study. We would also like to thank stakeholders from mental health support organisations who helped to generate the implications of this research at a stakeholder event.

Disclosure statement

All authors are (partially) based at King’s College London which, for the purpose of other military-related studies, receives funding from the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). S.A.M.S., salary was partially paid by the UK MoD. The UK MoD provides support to the Academic Department of Military Mental Health, and the salary of N.G. is covered partly by this contribution. N.G. is the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Lead for Military and Veterans’ Health, a trustee of Walking with the Wounded, and an independent director at the Forces in Mind Trust; however, he was not directed by these organisations in any way in relation to his contribution to this paper. S.W. is a trustee (unpaid) of Combat Stress and Honorary Civilian Consultant Advisor in Psychiatry for the British Army (unpaid). S.W. and N.G. are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London in partnership with Public Health England, in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and Newcastle University. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, Public Health England or the UK MoD.

References

- Andersen R., & Newman J. F. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Quarterly, 51, 95–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H., Cousins R., & Young C. (2014). Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Comprehensive Psychology, 3(4). [Google Scholar]

- Archer M., Rafferty L. A., Harwood H., Stevelink S. A. M., & Greenberg N. (2019). The Helping Armed Forces Loved Ones (HALO) study. Report by King’s Centre for Military Health Research and help for heroes. (Currently in Preparation).

- Babor T. F., Higgins-Biddle J. C., Saunders J. B., & Monteiro M. G. (2001). AUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman S. J., Stevelink S. A. M., Hatch S. L., Denny J. A., & Greenberg N. (2017). Stigma-related barriers and facilitators to help seeking for mental health issues in the armed forces: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Psychological Medicine, 47(11), 1880–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes C. R., Kuhn E., Gifford E., Spoont M. R., Meis L. A., Polusny M. A., … Wright J. (2015). A pilot trial of VA-CRAFT: Online training to enhance family well-being and Veteran mental health service use. Paper presented at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- Fear N. T., Iversen A., Meltzer H., Workman L., Hull L., Greenberg N., … Wessely S. (2007). Patterns of drinking in the UK Armed Forces. Addiction, 102, 1749–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear N. T., Jones M., Murphy D., Hull L., Iversen A. C., Coker B., … Wessely S. (2010). What are the consequences of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the mental health of the UK armed forces? A cohort study. The Lancet, 375(9728), 1783–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D., & Huxley P. (1980). Mental illness in the community: The pathway to psychiatric care. London: Tavistock Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. P., Gater R., Sartorious N., Ustun T. B., Piccinelli M., Gureje O., & Rutter C. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene-Shortridge T. M., Britt T. W., & Castro C. A. (2007). The stigma of mental health problems in the military. Military Medicine, 172(2), 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopf M., Hull L., Fear N. T., Browne T., Horn O., Iversen A., … Wessely S. (2006). The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: A cohort study. The Lancet, 367(9524), 1731–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huck C. (2014). Barriers and facilitators in the pathway to care of military veterans. London, UK: University College London. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen A. (2013). The psychological health of veterans of the 2003 Iraq war (Ph.D. Thesis). University of London, King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen A., Nikolaou V., Greenberg N., Unwin C., Hull L., Hotopf M., … Wessely S. (2005). What happens to British veterans when they leave the Armed Forces? European Journal of Public Health, 15(2), 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen A. C., van Staden L., Hacker Hughes J., Browne T., Greenberg N., Hotopf M., … Fear N. T. (2010). Help-seeking and receipt of treatment among UK service personnel. British Journal Psychiatry, 197(2), 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen A. C., van Staden L., Hacker Hughes J., Greenberg N., Hotopf M., Rona R. J., … Fear N. T. (2011). The stigma of mental health problems and other barriers to care in the UK Armed Forces. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 11–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M., Hoerster K. D., Blais R. K., Malte C. A., Hunt S., & Seal K. (2013). Readiness for change predicts VA mental healthcare utilization among Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(1), 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus S., Bebbington P., Jenkins R., & Brugha T. (eds.). (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Mellotte H., Murphy D., Rafferty L., & Greenberg N. (2017). Pathways into mental health care for UK veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Defence (2016). UK Armed Forces biannual diversity statistics April 2016. UK: Defence Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Defence (2017). Veterans: Key facts. Retrieved from https://www.armedforcescovenant.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Veterans-Key-Facts.pdf

- Murphy D., Palmer E., & Busuttil W. (2017). Exploring indices of multiple deprivation within a sample of veterans seeking help for mental health difficulties residing in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Reviews, 1(6). [Google Scholar]

- NVivo qualitative data analysis Software (2012). Version 10 QSR International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., & Velicer W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Lewis J., McNaughton Nicholls C., & Ormston R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N., Angermeyer M. C., & Corrigan P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B., Sim J., Kingstone T., Baker S., Waterfield J., Bartlam B., … Jinks C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer N. A., Freidemann-Sanchez G., Spoont M., Murdoch M., Parker L. E., Chiros C., & Rosenheck R. (2009). A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry, 72(3), 238–255. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M. L., Fear N. T., Rona R. J., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Jones N., & Goodwin L. (2015). Stigma as a barrier to seeking health care among military personnel with mental health problems. Epidemiological Reviews, 37(1), 144–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. E., & Meyers R. J. (2004). Motivating substance abusers to enter treatment: Working with family members. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevelink S. A. M., Jones M., Hull L., Pernet D., MacCrimmon S., Goodwin L., … Wessely S. (2018). Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: A cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(6), 690–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevelink S. A. M., Jones N., Jones M., Dyball D., Khera C. K., Pernet D., … Fear N. T. (2019). Do serving and ex-serving personnel of the UK armed forces seek help for perceived stress, emotional or mental health problems? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin J., Herrell R. K., Hoge C. W., Fear N. T., Adler A. B., Greenberg N., … Bliese P. D. (2014). Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(3), 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toerien M., & Wilkinson S. (2004). Exploring the depilation norm: A qualitative questionnaire of women's body hair removal. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1(1), 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- True G., Rigg K. K., & Butler A (2015). Understanding barriers to mental health care for recent war veterans through photovoice. Qualitative Health Research, 25(10), 1443–1455. doi: 10.1177/1049732314562894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Huska J., & Keane T. M. (1994). The PTSD checklist – Civilian version (PCL-C). Boston: National Centre for PTSD- Behavioural Science Division. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ministry of Defence (2017). Veterans: Key facts. Retrieved from https://www.armedforcescovenant.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Veterans-Key-Facts.pdf