Abstract

Background

The metabolic syndrome is a clustering of hyperglycemia/insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and stroke, and all-cause mortality. The burden of metabolic syndrome is emerging alarmingly in low- and middle-income countries such as Ethiopia; however, there is lack of comprehensive estimation. This study aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis included original articles of observational studies published in the English language. Searches were carried out in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Africa Journals from conception to August 2020. A random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Subgroup analysis was also conducted based on sex/gender and study subjects. Egger's test was used to assess publication bias.

Results

Electronic and gray literature search retrieved 942 potentially relevant papers. After removing duplicates and screening with eligibility criteria, twenty-eight cross-sectional studies were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia was found to be 34.89% (95% CI: 26.77, 43.01) and 27.92% (95% CI: 21.32, 34.51) by using NCEP/ATP III and IDF criteria, respectively. The weighted pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher in females 36.74% (95% CI: 20.72, 52.75) and 34.09% (95% CI: 26.68, 41.50) compared to males 22.22% (95% CI: 14.89, 29.56) and 24.82% (95% CI: 18.34, 31.31) by using IDF and NCEP/ATP III criteria, respectively. Subgroup analysis based on the study subjects using NCEP/ATP III showed that the weighted pooled prevalence was 63.78%(95% CI: 56.17, 71.40), 44.55% (95% CI: 30.71, 52.38), 23.09% (95% CI: 19.74, 26.45), 20.83% (95% CI: 18.64, 23.01), and 18.45% (95% CI: 13.89, 23.01) among type 2 diabetes patients, hypertensive patients, psychiatric patients, HIV patients on HAART, and working adults, respectively. The most frequent metabolic syndrome components were low HDL-C 51.0% (95% CI: 42.4, 59.7) and hypertriglyceridemia 39.7% (95% CI: 32.8, 46.6).

Conclusions

The findings revealed an emerging high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia. Therefore, early intervention is required for the primary prevention of the occurrence of metabolic syndrome and the further reduction of the morbidity and mortality related to it.

1. Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of interrelated risk factors that have been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, diabetes mellitus, and other comorbidities [1, 2]. Insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension are considered to be the primary components of MetS [3, 4]. The worldwide prevalence of MetS and noncommunicable chronic diseases in the adult population is on the rise [5]. It has been estimated that the prevalence of MetS ranges 20–25% of the adult population globally [6]. The epidemiologic nature of MetS is also emerging alarmingly and being common in Africa in contrast to the earlier trend of being considered rare. The increase in the prevalence of MetS in Africa is thought to be due to divergence from traditional African to Western lifestyles [7]. High prevalence of MetS has been reported in some sub-Saharan Africa countries such as in Morocco (16.3%) and South Africa (33.5%) [8].

The individual with MetS has 2-3 times higher chance of developing stroke and CVD than without MetS [9, 10]. It has also a six-fold greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [11]. T2DM has become one of the major causes of premature illness and death, mainly through the increased risk of CVD disease [12]. MetS is also associated with other comorbidities such as cancer, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other reproductive disorder [13–15]. It is also suggested that mortality due to MetS is more than twice that without the syndrome [16]. The prevalence of MetS varies across different populations. MetS appear to be more common in the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and HIV infection than their counterparts. Around 85% of those with diabetes have MetS in the United States in contrast to 25% of working adults in Europe and Latin America [17, 18]. Likewise, the high prevalence of HIV infection in developing countries and concomitant antiretroviral therapy is also associated with the rise of MetS [19]. Todowede O. O. et al. have reported in a meta-analysis that MetS prevalence among people living with HIV was 21.5% in contrast to uninfected 12.0% [20]. MetS rates are rising in developing countries in an epidemic situation [7]. For instance, in Ethiopia, the prevalence of MetS among T2DM, hypertensive, and HIV patients is estimated to be high [21–23]. The pathogenesis of the MetS is multidirectional, but obesity-induced insulin resistance is the major pathway for the occurrence of MetS [24]. Similarly, increased risk of MetS and its components is attributed to antiretroviral therapy and other related factors [25]. Sociodemographic factors, behavioral factors, stress, family history of disease, and some anthropometric measurements have been reported as associated factors of MetS in different literatures [26–28]. For instance, a study conducted among Malaysian population has showed that increasing age and low physical activity have been associated with increased odds of MetS [29].

Due to the dramatic increase in urbanization, smoking, severe stress-related problems of poverty, nutrition transition, reduced physical activity, and over nutrition increasing on top of the already high prevalence of undernutrition, sub-Saharan Africa is facing a rapid escalation of MetS and noncommunicable chronic diseases and associated mortality [30–32].

In Ethiopia, several studies were conducted to assess the prevalence of MetS among different study subjects having great disparity and inconsistent findings. However, there is lack of comprehensive estimation of MetS in Ethiopia. Hence, this systematic review aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of MetS among the Ethiopian population of various study subjects. This will provide the necessary information for policymakers, clinicians, and concerned stakeholders in the country to provide an appropriate strategy and intervene in the control, prevention, and management of MetS.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Search Strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement guideline. The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42018090944) [33]. An inclusive literature search was conducted to identify studies about the prevalence of MetS reported among the Ethiopian population of various study subjects. Both electronic and gray literature searches were carried out systematically. PubMed, African journal of Medline, and Google Scholar were used to retrieve data. The search terms were used separately and in combination using Boolean operators like “OR” or “AND.” An example of keywords used in PubMed to select relevant studies was as follows: [((Metabolic syndrome [Title/Abstract]) OR (MS [Title/Abstract]) OR (MetS [Title/Abstract]) OR (Insulin resistance syndrome [Title/Abstract]) OR (syndrome X [Title/Abstract]) OR (MtS [Title/Abstract])) AND (Ethiopia [Title/Abstract])]. Moreover, a snowball search was used to search the citation lists of included studies. The search incorporated studies recorded up to the 30th of August 2020. The software EndNote version X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY) was used to manage references and remove duplicated references.

2.2. Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of MetS based on the International Diabetes Federation [6] and National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III) criteria [34] (Table 1) among different study subjects in Ethiopia.

Table 1.

Definitions of metabolic syndrome by using NCEP/ATPIII and IDF criteria.

| NCEP/ATPIII | IDF | |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutely required | None | Central obesity (waist circumference§): 94 cm (M) and ≥80 cm (F) |

| Criteria | Any three of the five criteria below | Obesity, plus two of the four criteria below |

| Obesity | Waist circumference: >40 inches (M) and >35 inches (F) | Central obesity already required |

| Hyperglycemia | Fasting glucose >100 mg/dl or Rx | Fasting glucose> 100 mg/dl |

| Dyslipidemia | TG > 150 mg/dl or Rx | TG > 150 mg/dl or Rx |

| Dyslipidemia (second, separate criteria) | HDL-C: <40 mg/dl (M) and <50 mg/dl (F) or Rx | HDL-C: <40 mg/dl (M) and <50 mg/dl (F) or Rx |

| Hypertension | >130 mmHg systolic or > 85 mmHg diastolic or Rx | >130 mmHg systolic or > 85 mmHg diastolic or Rx |

Rx, pharmacologic treatment; NCEP/ATPIII, National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

2.3. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

Observational studies (all of them were cross-sectional studies) that described the prevalence of MetS among the indigenous Ethiopian population were included. All included studies were original research articles published in English and contained the minimum information (study participants and number of MetS cases). Moreover, studies in which MetS has been reported using (i) IDF criteria and/or (ii) NCEP/ATPIII were included. The full text of studies meeting these criteria was retrieved and screened to determine its eligibility. Whereas studies in which MetS was described on other than the Ethiopian population, nonoriginal research (such as review, editorial, and a letter or commentary), and unknown/unclear methods of how MetS was diagnosed were not included.

2.4. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (S.A. and M.M.) independently screened the titles and abstracts in the abovementioned databases to consider the articles in the full-text review. The quality of the studies was appraised using Joanna Brigg's Institute quality appraisal criteria (JBI) [35]. All selected articles were evaluated by using the JBI appraisal checklist. Studies that got 50% and above on the quality scale were considered to have good quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment of included studies using Joanna Brigg's Institute quality appraisal criteria scale (JBI).

| Study [Ref.]/Year | Was the sample representative of the target population? | Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way? | Was the sample size adequate? | Were the study subjects and setting described in detail? | Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | Were objective standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Was the condition measured reliably? | Are all the important confounding factors/subgroups/differences identified and accounted for? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mossie et al. [36]/2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tachebele et al. [37]/2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bosho et al. [38]/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hirigo et al. [39]/2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tran et al. [40]/2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes |

| Tesfaye et al. [41]/2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Biadgo et al. [42]/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Birarra et al. [43]/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Solomon et al. [44]/2020 | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gebremeskel et al. [45]/2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bune et al. [46]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gebremariam et al. [47]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Asaye et al. [48]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wube et al. [49]/2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Teshome et al. [50]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gebreyes et al. [51]/2018 | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes |

| Kerie et al. [52]/2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gebrehiwot et al. [53]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ataro et al. [54]/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Melak et al. [55]/2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear |

| Geto et al. [56]/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

2.5. Data Extraction

To collect relevant data, a data extraction tool was developed, and one reviewer (SA) was responsible for the extraction of data from the included studies. Information regarding authors, year of publication, the study population, type of study/study design, number of participants, gender, diagnostic criteria for defining Mets, region, study area, sampling techniques, and the prevalence of MetS in each study were collected. The extracted data were checked by the second reviewer (AE) for its accuracy and consistency. A third reviewer (YT) was also engaged where necessary.

2.6. Data Analysis

The extracted data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp. 2009. Stata Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). A random-effects model was used to obtain an overall summary estimate of the prevalence across studies. Point estimation with a confidence interval of 95% was used. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the role of each study in the final result by excluding each study one by one. The presence of publication bias was assessed by using Egger's test. Trim and fill method analyses have been conducted to obtain a bias-adjusted effect estimate. Heterogeneity across studies was checked by Cochran's Q statistic and I2 statistics. Moreover, meta-regression has been conducted that represent linear predictions for the MetS prevalence as a function of published year. Subgroup analysis was performed based on sex/gender, and study subjects since there have unexplained significant heterogeneity.

3. Result

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

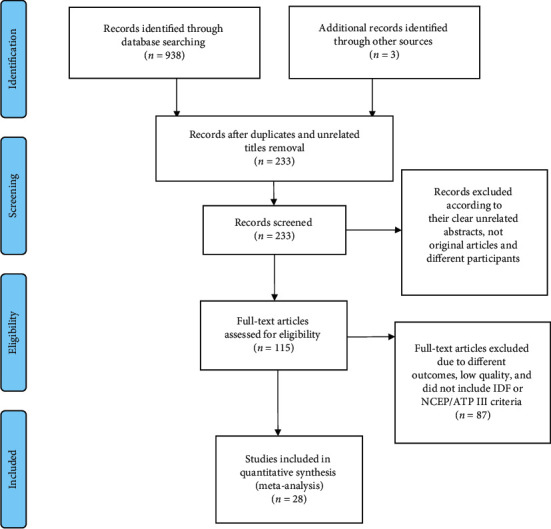

Out of 942 potential articles, 233 articles were found to be relevant to the topic of interest screened by title and abstract. Then, 115 were found to be eligible for full-text assessment. Of these full-text screened articles, 28 of them comprising 20652 study participants were found to be eligible for meta-analysis (Table 3). Figure 1 showed the results of the search and reasons for exclusion during the study selection process.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of the included studies (n = 28).

| Study [Ref.]/Year | Region | Sampling techniques | Study area | Study subjects | Sample Size, n | P% (IDF) | P% (NCEP/ATPIII) | Quality score by JBI criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berhan et al. [57]/2012 | Oromia | MPSSS | Jimma | HIV on HAART | 313 | — | 21.1 | Good |

| Mossie et al. [36]/2016 | Oromia | MPSSS | Jimma | Working adults | 1316 | 16.7 | 10.5 | Good |

| Tachebele et al. [37]/2014 | Amhara | SRST | Gondar | Hypertensive | 300 | 39.3 | 40.7 | Good |

| Tadewos et al. [58]/2018 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | Hypertensive | 238 | — | 48.7 | Good |

| Woyesa et al. [59]/2017 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | T2DM patients | 314 | — | 70.1 | Good |

| Bosho et al. [38]/2018 | Oromia | SRST | Jimma | HIV on HAART | 268 | 20.5 | 23.5 | Good |

| Hirigo et al. [39]/2016 | SNNP | NA | Hawassa | HIV on HAART | 185 | 24.3 | 17.8 | Good |

| Tran et al. [40]/2011 | Addis Ababa | MPSSS | Addis Ababa | Working adults | 1935 | 17.9 | 12.5 | Good |

| Abda et al. [60]/2016 | Oromia | CST | Jimma | Working adults | 225 | — | 26 | Good |

| Tadewos et al. [61]/2017 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | T2DM patients | 270 | — | 45.9 | Good |

| Tesfaye et al. [41]/2014 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | HIV on HAART | 188 | 25 | 18.1 | Good |

| Biadgo et al. [42]/2018 | Amhara | SRST | Gondar | T2DM patients | 159 | 53.5 | 66.7 | Good |

| Birarra et al. [43]/2018 | Amhara | SRST | Gondar | T2DM patients | 256 | 57 | 70.3 | Good |

| Solomon et al. [44]/2020 | Addis Ababa | NA | Addis Ababa | Working adults | 325 | 8.6 | 20.3 | Good |

| Gebremeskel et al. [45]/2019 | Tigray | SRST | Mekele | T2DM patients | 419 | 51.1 | — | Good |

| Bune et al. [46]/2020 | SNNP | SRST | Gedeo zone | HIV on HAART | 422 | 22 | — | Good |

| Gebremariam et al. [47]/2020 | Tigray | Survey | Mekele | Working adults | 1380 | 40.7 | — | Good |

| Asaye et al. [48]/2020 | Oromia | CST | Jimma | Psychiatric patients | 360 | 28.9 | 22.2 | Good |

| Wube et al. [49]/2019 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | T2DM patients | 314 | 52.9 | 70.1 | Good |

| Teshome et al. [50]/2020 | SNNP | SRST | Hawassa | Psychiatric patients | 245 | 26.9 | 24.5 | Good |

| Zerga et al. [62]/2020 | Amhara | CST | Desie | T2DM patients | 330 | - | 59.4 | Good |

| Gebreyes et al. [51]/2018 | All regions | NA | — | Working adults | 8673 | 4.8 | — | Good |

| KerieS et al. [52]/2019 | SNNP | SRST | Mizan-Aman | Working adults | 534 | 9.6 | — | Good |

| Gebrehiwot et al. [53]/2020 | Tigray | SRST | Mekele | Working adults | 266 | 21.8 | — | Good |

| Ataro et al. [54]/2020 | Eastern Ethiopia | CST | Harar | HIV on HAART | 375 | 26.7 | 22.1 | Good |

| Cheneke et al. [63]/2019 | Eastern Ethiopia | CST | Harar | Working adults | 365 | - | 27.7 | Good |

| Melak et al. [55]/2016 | Amhara | SRST | Gondar | Working adults | 227 | 13.6 | — | Good |

| Geto et al. [56]/2018 | Addis Ababa | CST | Addis Ababa | Working adults | 450 | 27.6 | 16.7 | Good |

NCEP/ATPIII, National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; MPSSS, multistage probabilistic stratified sampling strategy; SRST, simple/systematic random sampling technique; CST, consecutive sampling technique; SNNP, South Nation Nationality and People; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; JBI, Joanna Brigg's Institute quality appraisal.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing the steps of article inclusion to this systematic review.

The prevalence of MetS was estimated based on the IDF and NCEP/ATPIII criteria among the Ethiopian population of various study subjects. Fourteen studies reported the prevalence of MetS based on both IDF and NCEP/ATPIII criteria [36–44, 48–50, 54, 56], seven studies based on NCEP/ATPIII criteria only [57–63], and again seven studies by IDF criteria only [45–47, 51–53, 55]. Table 3 presents the characteristics and outcomes of the reviewed studies.

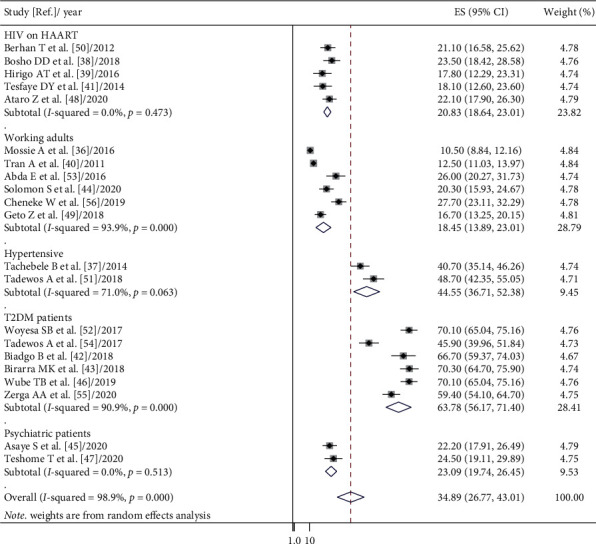

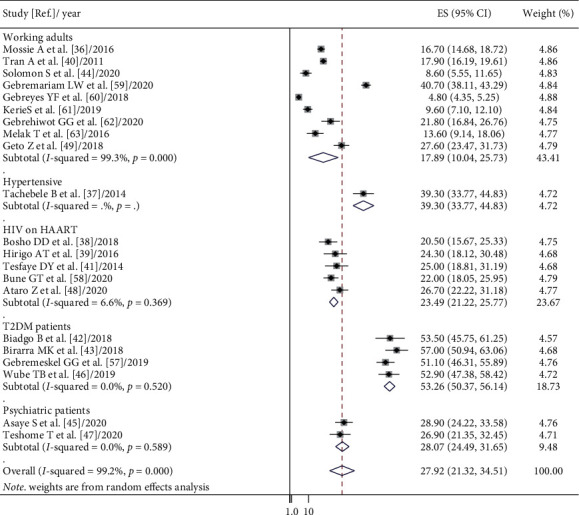

3.2. Prevalence of MetS Using IDF and NCEP ATP III Criteria

The random-effects model was applied since the heterogeneity index of the studies was significant. The pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia was found to be 34.89% (95% CI: 26.77, 43.01) and 27.92% (95% CI: 21.32, 34.51) by using NCEP/ATP III and IDF criteria, respectively. Subgroup analysis based on the study subjects using NCEP/ATP III showed that the weighted pooled prevalence was 63.78% (95% CI: 56.17, 71.40), 44.55% (95% CI: 30.71, 52.38), 23.09% (95% CI: 19.74, 26.45), 20.83% (95% CI: 18.64, 23.01), and 18.45% (95% CI: 13.89, 23.01) among type 2 diabetes patients, hypertensive patients, psychiatric patients, HIV patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and working adults, respectively. Using IDF criteria, subgroup analysis based on the study subjects showed that the weighted pooled prevalence was 53.26% (95% CI: 50.37, 56.14), 39.30% (95% CI: 33.77, 44.83), 20.07% (95% CI: 24.49, 31.65), 23.49% (95% CI: 21.22, 25.77), and 17.89% (95% CI: 10.04, 25.73) among type 2 diabetes patients, hypertensive patients, psychiatric patients, HIV patients on HAART, and working adults, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). The weighted pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher in females 36.74% (95% CI: 20.72, 52.75) and 34.09% (95% CI: 26.68, 41.50) compared to males 22.22% (95% CI: 14.89, 29.56) and 24.82% (95% CI: 18.34, 31.31) by using IDF and NCEP/ATP III criteria, respectively (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of metabolic syndrome prevalence in Ethiopia based on NCEP/ATP III criteria.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of metabolic syndrome prevalence in Ethiopia based on IDF criteria.

Table 4.

Pooled estimates of metabolic syndrome based on sex/gender.

| Study/Year | Sample size (male) | Sample size (female) | P% male by NCEP/ATP III | P% female by NCEP/ATP III | P% male by IDF | P% female by IDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berhan et al. [57]/2012 | 109 | 204 | 17.4 | 23 | — | — |

| Mossie et al. [36]/2016 | 620 | 696 | 6 | 14.5 | 11.1 | 21.7 |

| Tachebele et al. [37]/2014 | 115 | 185 | 12 | 28.7 | 9.3 | 30.3 |

| Tadewos et al. [58]/2018 | 105 | 133 | 37.9 | 62.1 | — | — |

| Bosho et al. [38]/2018 | 57 | 211 | 21 | 24.2 | — | — |

| Hirigo et al. [39]/2016 | 68 | 117 | 17.6 | 17.9 | 8.8 | 33.3 |

| Tran et al. [40]/2011 | 1171 | 764 | 10 | 16.2 | — | — |

| Abda et al. [60]/2016 | 106 | 119 | 16 | 35.3 | 14 | 24 |

| Tadewos et al. [61]/2017 | 166 | 104 | 36.7 | 60.6 | — | — |

| Tesfaye et al. [41]/2014 | 126 | 248 | 18.3 | 16.1 | 15.1 | 28.2 |

| Biadgo et al. [42]/2018 | 64 | 95 | 56.3 | 73.7 | — | — |

| Birarra et al. [43]/2018 | 113 | 143 | 33.9 | 66.1 | 27.4 | 72.6 |

| Solomon et al. [44]/2020 | 155 | 170 | 18.1 | 22.4 | 1.9 | 14.7 |

| Gebremeskel et al. [45]/2019 | 208 | 211 | — | — | 42.5 | 57.5 |

| Gebremariam et al. [47]/2020 | 823 | 557 | — | — | 41.1 | 40.2 |

| Asaye et al. [48]/2020 | 229 | 131 | 11.4 | 17.5 | — | — |

| Wube et al. [49]/2019 | 211 | 103 | 69.7 | 70.9 | 32.7 | 94.2 |

| Teshome et al. [50]/2020 | 143 | 102 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 47 | 53 |

| Zerga et al. [62]/2020 | 170 | 160 | — | — | — | — |

| Gebreyes et al. [51]/2018 | 1306 | 7367 | — | — | 8.6 | 1.8 |

| KerieS et al. [52]/2019 | 271 | 263 | 6.6 | 12.5 | — | — |

| Gebrehiwot et al. [53]/2020 | 124 | 142 | — | — | 18.5 | 24.6 |

| Cheneke et al. [63]/2019 | — | 365 | −202 | 27.7 | — | — |

| Geto et al. [56]/2018 | 232 | 218 | 19.4 | 13.8 | 35.8 | 18.8 |

| Combined pooled estimate (95% CI: LCI, UCI) | 24.82% (95% CI: 18.34, 31.31) | 34.09% (95% CI: 26.68, 41.50) | 22.22% (95% CI: 14.89, 29.56) | 36.74% (95% CI: 20.72, 52.75) |

NCEP/ATPIII, National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval.

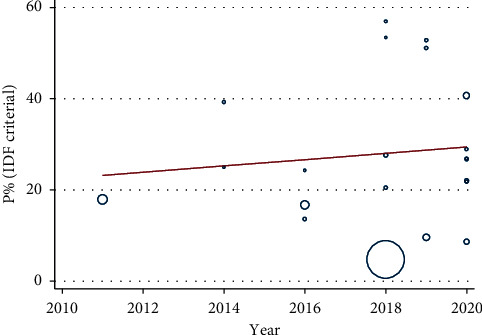

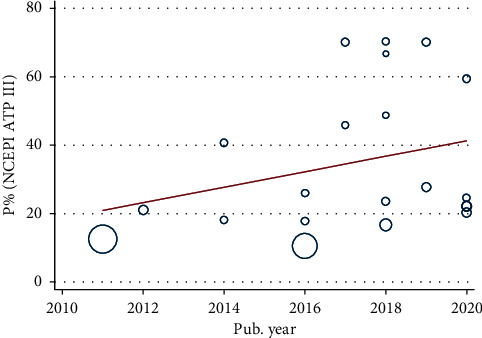

Moreover, meta-regression has been conducted that characterize the linear predictions for the prevalence of MetS as a function of the increment of published year (Figures 4 and 5). An increasing trend in pooled prevalence of MetS is observed during the 2010–2020 time period in both IDF and NCEP/ATP III criteria.

Figure 4.

Meta-regression analysis based on published year using IDF criteria.

Figure 5.

Meta-regression analysis based on published year using NCEP/ATP III criteria.

3.3. Prevalence of the MetS Components

The prevalence of the individual components of MetS among the Ethiopian population varied considerably between studies (Table 5). In 22 studies, the overall prevalence of individual components of MetS was reported, whereas in 6 studies, the prevalence of individual components of MetS was not reported. The overall weighted pooled prevalence by the component was as follows: abdominal obesity 35.85% (95% CI: 28.9, 42.8), hyperglycemia 26.4% (95% CI: 20, 32.8), hypertension 27.87% (95% CI: 23.4, 32.2), hypertriglyceridemia 39.7% (95% CI: 32.8, 46.6), and low HDL-C 51.0 (95% CI: 42.4, 59.7) are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Pooled estimates of metabolic syndrome components.

| Authors | Sample size | Prevalence of metabolic syndrome components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Hyperglycemia | Low HDL-C | Central obesity | Elevated triglyceride | ||

| Berhan et al. [57] | 313 | 16 | 24.9 | 46 | 13.7 | 39 |

| Tachebele et al. [37] | 300 | — | 25.3 | 81.3 | 18.7 | 27.3 |

| Tadewos et al. [58] | 238 | — | 35.7 | 60.9 | 37.8 | 62.2 |

| Woyesa et al. [59] | 319 | 25.5 | 80 | 39.2 | 61.3 | 70.4 |

| Bosho et al. [38] | 268 | 38.4 | 17.2 | 49.3 | 18.7 | 29.9 |

| Hirigo et al. [39] | 185 | 9.72 | 14.59 | 70.27 | 22.7 | 44.86 |

| Tran et al. [40] | 1935 | 20.65 | 19.97 | 23.32 | 18.5 | 20.59 |

| Abda et al. [60] | 225 | 45 | 39 | 31 | 26 | 18 |

| Tadewos et al. [61] | 270 | 28.1 | — | 47 | 40.7 | 68.1 |

| Esfaye et al. [41] | 188 | 23.9 | 33.5 | 53.7 | 52.7 | 45.2 |

| Biadgo et al. [42] | 159 | 55.4 | — | 32.7 | 43.4 | 56.6 |

| Melak et al. [55] | 220 | 15.5 | 8.6 | 68.6 | 17.7 | 26.8 |

| Ataro et al. [54] | 375 | 10.9 | 18.4 | 64.5 | 59.2 | 41.9 |

| Birarra et al. [43] | 256 | 43 | — | 66.8 | 16.4 | 67.6 |

| Bune et al. [46] | 422 | 56.6 | 56.4 | 30.8 | 49.1 | 42.9 |

| Gebremariam et al. [47] | 1380 | 19.6 | 19.4 | 71.6 | 42.7 | 55.7 |

| Gebremeskel et al. [45] | 419 | 41.3 | — | 34.4 | 59.7 | 45.1 |

| Gebreyes et al. [51] | 8673 | 15.8 | 9.1 | 68.7 | 39.8 | 21.0 |

| Geto et al. [56] | 450 | 23.6 | 2.4 | 41.3 | 80.2 | 19.3 |

| Kerie S et al. [52] | 534 | 16.9 | 7.1 | 50.9 | 26.22 | 22.8 |

| Solomon S et al. [44] | 325 | 36.3 | 32.6 | 48.6 | 19.4 | 24.0 |

| Teshome T et al. [50] | 245 | 22.0 | 34.3 | 41.2 | 24.9 | 26.9 |

| Combined pooled estimates (LCI, UCI) | 27.87 (23.4, 32.2) | 26.4 (20, 32.8) | 51.0 (42.4, 59.7) | 35.85 (28.9, 42.8) | 39.7 (32.8, 46.6) | |

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the effect of each study on the pooled estimated prevalence of MetS by excluding each study step-by-step from the analysis process based on the two given diagnostic criteria (IDF and NCEP/ATP III). The result showed that excluded studies led to no significant changes in the shared estimation of the prevalence of MetS (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis based on NCEP/ATP III criteria.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis based on IDF criteria.

3.5. Publication Bias

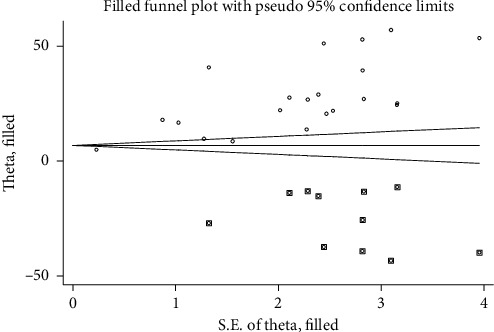

The included studies were assessed for potential publication bias using Egger's test. Separate analyses using Egger's test based on IDF and NCEP/ATPIII criteria (p values were 0.001 and 0.001, respectively) indicated the presence of publication bias. This indicates that the unpublished findings might have shown a larger magnitude of MetS. Adjusting the findings using the trim and fill method would provide a bias-adjusted effect estimate. Therefore, to do so, we have conducted trim and fill method analysis. A bias-adjusted effect estimate of MetS showed 9.67 % (95% CI: 3.16, 16.19) and 15.67% (95% CI: 6.79, 24.55) by using IDF and NCEP/ATPIII criteria, respectively, assuming there are missing studies (Figures 8 and 9). However, there was somehow a difference compared with our previous results indicating minimally impacted by publication bias.

Figure 8.

Trim and fill analysis based on NCEP/ATP III criteria.

Figure 9.

Trim and fill analysis based on IDF criteria.

4. Discussion

The current systematic review provides evidence of an estimated pooled prevalence of MetS among various study subjects of the Ethiopian population. According to this review, the combined pooled prevalence of MetS was 34.89% (95% CI: 26.77, 43.01) and 27.92% (95% CI: 21.32, 34.51) by using NCEP/ATP III and IDF criteria, respectively. These results were slightly in line with the reports in Brazil (29.6%) [64], Bangladesh (30%) [65], Iran 31% [66], and the United States (33%) [67]. But the current pooled estimate was also higher than the prevalence estimated in Ghana (12.4%) [68], Philippine (11.9%) [69], and the global estimate (20–25%) [6]. The findings were also lower as compared to Palestine (37.0%) [70], the Greek population (43.4%) [71], and the population of Nepal (52.7%) [72]. The variation in reports might be due to the difference in the underling important risk factors such as urbanization, westernization of lifestyle including unhealthy diet and physical inactivity [73], mental stress due to economic, social, and cultural factors [74], genetics, proinflammatory condition [75], intrauterine growth retardation, and over nutrition increasing on top of the already high prevalence of under nutrition [76].

The prevalence of MetS was high (34.89%) when NCEP/ATPIII criteria was used compared to IDF criteria (27.92%) in the current meta-analysis. These might be due to the relative flexibility of the NCEP/ATPIII in which central obesity is not the absolutely required criterion, unlike IDF [77]. However, it was different from a systematic review conducted among the Ghanaian population using these two criteria, NCEP/ATPIII (12.4%) and IDF criteria (21.2%) [68]. The discrepancy between the results of different studies could be attributed to the difference in abdominal obesity and waist circumference in different populations.

We observed high between-study heterogeneity across studies. In the subgroup analysis, the pooled prevalence of MetS using NCEP ATP III criteria was 63.78% among T2DM patients which was higher than the result of the rest of the study subjects, 18.45%, 20.83%, 23.09%, and 44.55% among working adults, HIV patients on HAART, psychiatric patients, and hypertensive patients, respectively. This is also the same using IDF criteria. Though hyperglycemia is one of the components of Mets that increased its prevalence, insulin resistance-linked obesity might be the aggravated reason for the high prevalence of MetS among T2DM patients. In T2DM patients, particularly when glycemic control is poor, lipoprotein lipase activity is reduced [78]. The reduced lipoprotein lipase activity added with poor dieting and lack of regular exercise might be the reason for the higher prevalence of MetS among T2DM patients [79].

In line with other reviews [66, 80], the current meta-analysis demonstrated that the prevalence rate of MetS was higher in females compared to that in males. This has been shown in all the Middle Eastern countries, and the prevalence was much higher among women than men [81]. The higher prevalence of MetS among the women is attributed to abdominal obesity, which is mainly due to low physical activity, higher birth rate, presence of estrogen receptors, and menopause [82]. Besides genetic variation, lifestyle might be the reason.

Low HDL-C was the most frequent individual component of MetS in the current meta-analysis which was similar to reports in Bangladesh (89%) [65], Colombia (62.9%) [18], and Venezuela (58.6%) [83]. However, hypertriglyceridemia was shown the second most prominent MetS component to the contrary high blood pressure report in Bangladesh (30%) [65]. The low concentration of HDL-C favors the accumulation of low-density lipoprotein in the blood vessels greatly due to its poor scavenging capacity of low-density lipoprotein from the body. The coexistence of hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL-C are risk factors for the development of CVD. It is well-known that a low concentration of the HDL-C level is a strong independent risk factor for CVD [84]. As a limitation to this review, a point needs to be noted that there is no uniformity of MetS definitions and waist circumference cutoffs points. Besides, high heterogeneity has been observed. Furthermore, there has been publication bias.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our review summarizes that a large proportion of the Ethiopian population have MetS regardless of the study subjects, gender, and the definitions used. One fact is clear here. MetS is growing at an alarming rate and is high in Ethiopia. Therefore, policymakers, clinicians, and concerned stakeholders shall urge effective strategies in the control, prevention, and management of MetS.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

Cardiovascular diseases

- IDF:

International Diabetes Federation

- HAART:

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- MetS:

Metabolic syndrome

- NCEP/ATP III:

National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

S.A. was involved in conception of the research protocol, design of the study, review of the literature, data extraction, and statistical analysis. S.A. and A.E. were involved in data analysis and interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. M.M. and A.W. were involved in data interpretation and review of the manuscript. S.A., Y.T., and B.B. were involved in data extraction and quality assessment. All authors critically revised the paper, and they agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Gami A. S., Witt B. J., Howard D. E., et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(4):403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy S. M., Brewer H. B., Cleeman J. I., Smith S. C., Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000111245.75752.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti K. G. M., Zimmet P., Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome-a new worldwide definition. The Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti K. G. M. M., Zimmet P., Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome-a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabetic Medicine. 2006;23(5):469–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alwan A., MacLean D. R., Riley L. M., et al. Monitoring and surveillance of chronic non-communicable diseases: progress and capacity in high-burden countries. The Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1861–1868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Group I. E. T. F. C.: International Diabetes Federation: The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. https://http://www idf org/webdata/docs/Metabolic_syndrome_def pdf 2005.

- 7.Okafor C. The metabolic syndrome in Africa: current trends. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;16(1):p. 56. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misra A., Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93(11_supplement_1):s9–s30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mottillo S., Filion K. B., Genest J., et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56(14):1113–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarrafzadegan N., Gharipour M., Sadeghi M., et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of ischemic stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2017;26(2):286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson P. W. F., D’Agostino R. B., Parise H., Sullivan L., Meigs J. B. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112(20):3066–3072. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martín-Timón I., Sevillano-Collantes C., Segura-Galindo A., del Cañizo-Gómez F. J. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: have all risk factors the same strength? World Journal of Diabetes. 2014;5(4):p. 444. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dibaba D., Braithwaite D., Akinyemiju T. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of breast cancer and subtypes by race, menopause and BMI. Cancers. 2018;10(9):p. 299. doi: 10.3390/cancers10090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehala-Aleksejev K., MJPo P. The effect of metabolic syndrome on male reproductive health: a cross-sectional study in a group of fertile men and male partners of infertile couples. World Journal of Diabetes. 2018;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194395.e0194395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamaguchi M., Kojima T., Takeda N., et al. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143(10):722–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzmarzyk P. T., Church T. S., Janssen I., Ross R., Blair S. N. Metabolic syndrome, obesity, and mortality: impact of cardiorespiratory fitness. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(2):391–397. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornier M.-A., Dabelea D., Hernandez T. L., et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29(7):777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Márquez-Sandoval F., Macedo-Ojeda G., Viramontes-Hörner D., Fernández Ballart J., Salas Salvadó J., Vizmanos B. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Latin America: a systematic review. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;14(10):1702–1713. doi: 10.1017/s1368980010003320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estrada V., Martínez-Larrad M. T., González-Sánchez J. L., et al. Lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. Metabolism. 2006;55(7):940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todowede O. O., Mianda S. Z., Sartorius B. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV-positive and HIV-negative populations in sub-Saharan Africa—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews. 2019;8(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0927-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abhayaratna S., Somaundaram N., Rajapakse H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among patients with type 2 diabetes. Sri Lanka Journal of Diabetes Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;5(2) doi: 10.4038/sjdem.v5i2.7286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadakis I., Vrentzos G., Zeniodi M., Ganotakis E. Pp.33.01: prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with essential hypertension in Greece. Journal of Hypertension. 2015;33:p. e429. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000468724.22222.a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obirikorang C., Quaye L., Osei-Yeboah J., Odame E., Asare I. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected patients in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Nigerian Medical Journal. 2016;57(2):p. 86. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.182082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canale M. P., Manca di Villahermosa S., Martino G., et al. Obesity-related metabolic syndrome: mechanisms of sympathetic overactivity. 2013;2013:13. doi: 10.1155/2013/865965. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ije/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez C., Salazar R., Galindez J., et al. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in latin America. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(3):256–263. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702010000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pyykkönen A.-J., Räikkönen K., Tuomi T., Eriksson J. G., Groop L., Isomaa B. Stressful life events and the metabolic syndrome: the prevalence, prediction and prevention of diabetes (PPP)-botnia study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):378–384. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das M., Pal S., Ghosh A. Family history of type 2 diabetes and prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adult Asian Indians. Journal of Cardiovascular Disease Research. 2012;3(2):104–108. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.95362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford E. S., Kohl H. W., Mokdad A. H., Ajani U. A. Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and the metabolic syndrome among U.S. Adults. Obesity Research. 2005;13(3):608–614. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iqbal S. P., Ramadas A., Fatt Q. K., Shin H. L., Onn W. Y., Kajpo K. Relationship of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors and diet habits with metabolic syndrome (MetS) among three ethnic groups of the Malaysian population. PLoS One. 2020;15(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224054.e0224054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motala A. A., Mbanya J.-C., Ramaiya K. L. Metabolic syndrome in sub-Saharan Africa. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(Suppl 2):S2–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young F., Critchley J. A., Johnstone L. K., Unwin N. C. A review of co-morbidity between infectious and chronic disease in Sub Saharan Africa: TB and diabetes mellitus, HIV and metabolic syndrome, and the impact of globalization. Globalization and Health. 2009;5(1):p. 9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cijijoe O. Metabolism: the metabolic syndrome in Africa. Current Trends. 2012;16(1):p. 56. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezaianzadeh A., Namayandeh S.-M., Mjijopm S. S. National cholesterol education program adult treatment panel III versus international diabetic federation definition of metabolic syndrome, which one is associated with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease? International Diabetes Federation. 2012;3(8):p. 552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munn Z., Moola S., Riitano D., Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2014;3(3):p. 123. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mossie A., Mezgebu Y. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in jimma town, South west Ethiopia. Valley International Journal. 2016;3(3) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tachebele B., Abebe M., Addis Z., NJBcd M. Metabolic syndrome among hypertensive patients at University of Gondar Hospital, North West Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. 2014;14(1):p. 177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-177. https://bmccardiovascdisord.biomedcentral.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosho D. D., Dube L., Mega T. A., Adare D. A., Tesfaye M. G., Eshetie T. C. J. D. Syndrome m: prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWHIV) 2018;10(1):p. 10. doi: 10.1186/s13098-018-0312-y. https://bmccardiovascdisord.biomedcentral.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirigo A. T., Dyjbrn T. Influences of gender in metabolic syndrome and its components among people living with HIV virus using antiretroviral treatment in Hawassa. Southern Ethiopia. 2016;9(1):p. 145. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1953-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran A., Gelaye B., Girma B., et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among working adults in ethiopia. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Tesfaye D. Y., Kinde S., Medhin G., et al. Burden of metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected patients in Southern Ethiopia. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2014;8(2):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biadgo B., Melak T., Ambachew S., et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at a tertiary hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2018;28(5) doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i5.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birarra M. K., Dajbcd G. Metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetic patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;18(1):p. 149. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon S., WJBcd M. Disease burden and associated risk factors for metabolic syndrome among adults in Ethiopia. Southern-Ethiopia Journal. 2019;19(1):p. 236. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1201-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gebremeskel G. G., Berhe K. K., Belay D. S., et al. Magnitude of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in ayder comprehensive specialized hospital, Tigray, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Journal of South West Ethiopia. 2019;12(1):p. 603. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4609-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bune G. T., Yalew A. W., Kumie A. J. The extents of metabolic syndrome among Antiretroviral Therapy exposed and ART naïve adult HIV patients in the Gedeo-zone, Southern-Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Journal of South West Ethiopia. 2020;78:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gebremariam L. W., Chiang C., Yatsuya H., et al. Non-communicable disease risk factor profile among public employees in a regional city in northern Ethiopia. Journal of Northern Ethiopia. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27519-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asaye S., Bekele S., Tolessa D., Cheneke W., Research M. S. C. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among psychiatric patients in jimma university specialized hospital, South west Ethiopia. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2018;12(5):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wube T. B., Nuru M. M., Anbese A. T. J. D. Metabolic Syndrome, Targets O, Therapy: a comparative prevalence of metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Hawassa university comprehensive specialized Hospital using four different diagnostic criteria. Medical Journal of Shree Birendra Hospital. 2019;12:p. 1877. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S221429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teshome T., Kassa D. H., Tadewos Hirigo A. Metabolic syndrome, targets O, therapy: prevalence and associated factors of metabolic syndrome among patients with severe mental illness at hawassa. Southern-Ethiopia Journal. 2020;13:p. 569. doi: 10.2147/dmso.s235379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gebreyes Y. F., Goshu D. Y., Geletew T. K., et al. Prevalence of high bloodpressure, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome and their determinants in Ethiopia: evidences from the National NCDs STEPS Survey, 2015. PLoS One. 2018;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194819.e0194819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kerie S., Menberu M., Mjpo G. Metabolic syndrome among residents of Mizan-Aman town, South West Ethiopia, 2017: A Cross Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2019;14(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210969.e0210969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gebrehiwot G. G., Belachew T., Mehari K., Tamiru D. Magnitude of metabolic syndrome and its components among adult residents of mekelle city, northern ethiopia, community-based cross-sectional study. 2020.

- 54.Ataro Z., WjeajoH A., Sciences B. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among adult HIV positive people on antiretroviral therapy in Jugal hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. Eastern-Ethiopia Journal. 2020;4(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melak T. D. S., Baynes H. W., Asmelash D., Biadgo B., Abebe A. S. Gondar, Ethiopia: University of Gondar; 2016. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated factors among academic staffs of university of gondar, northwest ethiopia. Master Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geto Zeleke S. D., Mariam Maria T. Addis Abeba, Ethiopia: Addis Abeba University; 2018. Assessment of cardiometabolic risks andassociated factors among ethiopian publichealth institute staff members. Master Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berhane T., Yami A., Alemseged F., et al. Prevalence of lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome among HIV positive individuals on Highly Active Anti-Retroviral treatment in Jimma, South West Ethiopia. Southern Ethiopia. 2012;13(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tadewos A., Egeno T., Ajbcd A. Risk factors of metabolic syndrome among hypertensive patients at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Southern Ethiopia. 2017;17(1):p. 218. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0648-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woyesa S. B., Hirigo A. T., Tbjbed W. Hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital. Journal of South West Ethiopia. 2017;17(1):p. 76. doi: 10.1186/s12902-017-0226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abda E., Hamza L., Tessema F., Cheneke W. J. D. Metabolic syndrome, targets o, therapy: metabolic syndrome and associated factors among outpatients of Jimma University Teaching Hospital. Journal of South West Ethiopia. 2016;9:p. 47. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S97561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tadewos A., Ambachew H., Assegu D. J. H. S. J. Pattern of metabolic syndrome in relation to gender among type-II DM patients in hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital, hawassa, southern Ethiopia. Journal of South West Ethiopia. 2017;11(3) doi: 10.21767/1791-809x.1000509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zerga A. A., Bezabih A. M., Adhanu A. K., Tadesse S. E. J. D. Metabolic syndrome, targets O, therapy: obesity indices for identifying metabolic syndrome among type two diabetes patients attending their follow-up in dessie referral hospital. North East Ethiopia. 2020;13:p. 1297. doi: 10.2147/dmso.s242792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheneke W., Sufa B. J. I. Metabolic syndrome among women using hormonal contraceptives IN harar town, eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern Ethiopia. 2019;7(10):400–406. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Carvalho Vidigal F., Bressan J., Babio N., Salas-Salvadó J. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Brazilian adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):p. 1198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chowdhury M. Z. I., Anik A. M., Farhana Z., et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Bangladesh: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):p. 308. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dalvand S., Niksima S. H., Meshkani R, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among iranian population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2017;46(4):p. 456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Zayadi A., Selim O., Hamdy H., Dabbous H., Ahdy A., Moniem S. Association of chronic hepatitis C infection and diabetes mellitus. Tropical Gastroenterology: Official Journal of the Digestive Diseases Foundation. 1998;19(4):141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ofori-Asenso R., Agyeman A. A., Laar A. Metabolic syndrome in apparently “healthy” Ghanaian adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Chronic Diseases. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2562374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ranasinghe P., Mathangasinghe Y., Jayawardena R., Hills A., Misra A. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the asia-pacific region: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):p. 101. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.el Bilbeisi A. H., Shab-Bidar S., Jackson D., Djafarian K. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related factors among adults in Palestine: a meta-analysis. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2017;27(1):77–84. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Athyros V. G., Ganotakis E. S., Tziomalos K., et al. Comparison of four definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a Greek (Mediterranean) population. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2010;26(3):713–719. doi: 10.1185/03007991003590597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maharjan B. R., Bhandary S., Shrestha I., Sunuwar L., Shrestha S. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in local population of patan. Medical Journal of Shree Birendra Hospital. 2012;11(1):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kubota M., Yoneda M., Maeda N, et al. Westernization of lifestyle affects quantitative and qualitative changes in adiponectin. BMC Public Health. 2017;16(1):p. 83. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0565-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lopuszanska U. J., Skorzynska-Dziduszko K., Lupa-Zatwarnicka K., MJAoA M.-S., Medicine E. Mental illness and metabolic syndrome-a literature review. BMC Public Health. 2014;21(4) doi: 10.5604/12321966.1129939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bahrami M., Cheraghpour M., Jafarirad S., Alavinejad P., Cheraghian B. J. N., Science F. The role of melatonin supplement in metabolic syndrome. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2019;31 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Desai M., Babu J., Ross M. G. J. A. Integrative, Physiology C: programmed metabolic syndrome: prenatal undernutrition and postweaning overnutrition. BMC Public Health. 2007;293(6):R2306–R2314. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00783.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Corona G., Mannucci E., Petrone L., et al. ENDOCRINOLOGY: a comparison of NCEP-ATPIII and IDF metabolic syndrome definitions with relation to metabolic syndrome-associated sexual dysfunction. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;4(3):789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grundy S. M., Cleeman J. I., Daniels S. R., et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart association/national heart, lung, and blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saiki A., Oyama T., Endo K., et al. Preheparin serum lipoprotein lipase mass might be a biomarker of metabolic syndrome. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;76(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sayehmiri F. Metabolic syndrome prevalence in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;36 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sliem H. A., Ahmed S., Nemr N., El-Sherif I. Metabolic syndrome in the Middle East. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;16(1):p. 67. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bentley-Lewis R., Koruda K., Seely E. W. J. N. C. P. E. Metabolism: the metabolic syndrome in women. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;3(10):696–704. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brajkovich I., González-Rivas J. P., Ugel E., Rísquez A., Nieto-Martínez R. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in three regions in Venezuela: the VEMSOLS study. International Journal of Cardiovascular Sciences. 2018;81 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adiels M., Olofsson S.-O., Taskinen M.-R. Thrombosis,, biology v: Overproduction of very low–density lipoproteins is the hallmark of the dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;28(7):1225–1236. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.