Abstract

Introduction and Background: Spontaneous rupture of the urinary collecting system with extravasation of urine is a rare complication of obstructive stone disease. Most of the cases are caused by obstructive ureteral stones. We herein present a case of a spontaneous caliceal rupture with a large perirenal urinoma formation that was silent on presentation and managed with endoscopic stenting and percutaneous catheter drainage.

Case Presentation: A 56-year-old man presented with complaints of vague right flank discomfort. A noncontrast CT scan revealed a 9.4 mm right mid ureteral obstructive calculus with a 14 cm collection in the perirenal space communicating with the lower calix of the right kidney. Retrograde insertion of 6F Double-J stent was done endoscopically and a pigtail catheter was placed in the right perinephric collection. Initially the catheter drained 100 mL clear urine and decreased progressively. A repeat ultrasonography revealed no collection and the catheter was removed after 10 days. The patient underwent clearance of stones after 8 weeks. On table, retrograde pyelogram showed no leak. The patient is doing well 2 weeks postoperatively.

Conclusions: Obstructive ureteral stone presenting with spontaneous forniceal rupture and large perinephric collection in a silent manner. Although endoscopic management alone offers excellent results in small ruptures, diversion of the collecting system with drainage of the collection remains the mainstay of treatment in large urinomas to prevent complications. Definitive management of the cause of obstruction is paramount and should be done after complete healing of the rupture.

Keywords: ureteral stone, caliceal rupture, pop-off mechanism, urinoma

Introduction

Spontaneous rupture of the urinary collecting system with extravasation of urine is a rare complication of obstructive stone disease. Most of the cases are caused by obstructive ureteral stones.1 Less common causes include pelvi ureteral junction obstruction, prostatic enlargement, or extrinsic compression of the ureters caused by gravid uterus, pelvic tumors, or retroperitoneal fibrosis. The site of rupture is most commonly the fornix, but rarely may involve the calices, pelvis, or the ureters.

Few cases of spontaneous rupture of the collecting system have been reported in the literature and most of them had small perirenal collections and were managed conservatively.2 We herein present a case of a spontaneous caliceal rupture with a large perirenal urinoma formation secondary to a small ureteral calculus that was silent on presentation and managed with endoscopic stenting and percutaneous catheter drainage.

Case Presentation

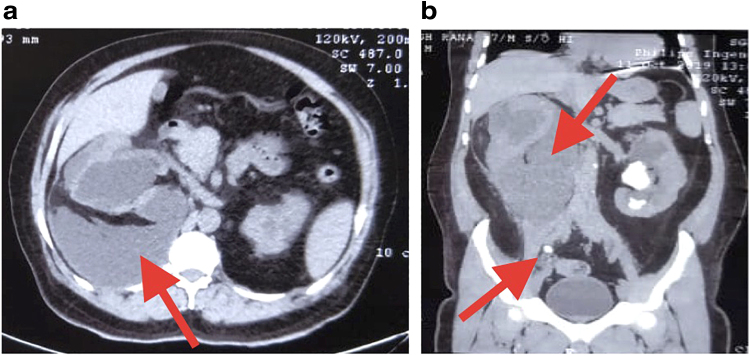

A 56-year-old man with no comorbidities presented to the outpatient department with complaints of vague right flank discomfort. He had no history of trauma. Urine microscopy was unremarkable and there was no leukocytosis. A preliminary ultrasonography showed bilateral hydronephrotic kidneys with left nephrolithiasis. In view of raised serum creatinine (1.8 mg/dL), a noncontrast CT scan was done. It revealed a 9.4 mm right mid ureteral obstructive calculus 8 cm below the pelviureteral junction and a 4 cm staghorn calculus in the left pelvis with bilateral gross hydronephrosis and parenchymal thinning (Fig. 1b). Also noted on the right side was a 14 × 12 cm collection in the perirenal space communicating with the lower calix of the right kidney and abutting the psoas muscle posteriorly (Fig. 1a). Retrograde insertion of 6F Double-J stent was done endoscopically uneventfully on both the sides and a 16F catheter was left in place to prevent reflux. Also, a 10F pigtail catheter was placed in the right perinephric collection as it was a large collection compressing the kidney and the patient complained of mild discomfort and heaviness.

FIG. 1.

Plain CT scan showing the (a) perirenal urinoma and the (b) causative obstructive right lower ureteral calculus. Also seen is the left staghorn calculus. Arrow in figure A indicates the perirenal urinoma. Arrows in figure B indicate the causative right lower ureteric calculus and the perirenal urinoma respectively.

Initially the catheter drained 150 mL clear fluid with a raised drain fluid creatinine (20.8 mg/dL), suggestive of urine and the output gradually decreased over the next few days. Fluid culture from the pigtail catheter showed no growth. A repeat ultrasonography revealed no collection and the pigtail catheter was removed after 10 days. With a sterile urine culture and a serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, the patient underwent clearance of stones on both the sides after 8 weeks (right ureteroscopic lithotripsy and left percutaneous nephrolithotomy [PCNL]). On table, right retrograde pyelogram showed no leak. Owing to early clearance of stone on the right side (30 minutes), the decision to continue with left prone PCNL in the same sitting was taken under general anesthesia with a total endoscopy time of 100 minutes. Complete stone clearance was achieved on the left side with an estimated blood loss of 150 mL and no intraoperative complications. Bilateral Double-J stents were placed as well as a nephrostomy tube on the left side. The patient is doing well 2 months postoperatively with stents and nephrostomy tube removed and his serum creatinine is 0.9 mg/dL.

Discussion

Extravasation of urine from the collecting system can occur because of leakage along any point starting from the calices down to the urethra. It is described as spontaneous when this occurs in the absence of trauma, surgery, or instrumentation. The most common cause of upper tract spontaneous urinary extravasation is downstream obstruction, which usually results from ureteral stones leading to increased intrarenal pressures and subsequent rupture.2

Any slow increase in intrarenal pressure is well compensated by increased back pressure, leading to increased renovascular resistance and decreased filtering capacity of nephrons leading to decreased urine formation. However, this process takes time. The hypothesis propagated in acute obstruction settings is a sudden rise in intrarenal collecting system pressure, which results from sudden downstream obstruction and reversal of urine flow. In accordance with the Laplace law (tension = pressure × radius), the stress induced in the calices increases proportionally with the radius, hence it is more in a grossly dilated system. When this stress increases beyond the inherent stress of the calices, they rupture leading to extravasation.2 This phenomenon is considered renoprotective and prevents further damage to the filtering nephrons.

Spontaneous ruptures may have a wide variety of presentations ranging from complete clinical silence to acute emergency. Usually the patient presents with symptoms of renal colic associated with nausea and vomiting because of irritation of the peritoneum. The sequelae of this condition include infection with abscess formation, sepsis, and acute kidney injury when left untreated.3

From a diagnostic point of view, ultrasonography can identify hydronephrosis, fluid collections, and presence of stones. However, the gold standard investigation is a CT scan with a delayed acquisition that will demonstrate the contrast extravasation and the exact site of rupture. As there are no guidelines or recommendations for this condition, various management options exist. Conservative management without diversion has been documented.4 Preferred management of small ruptures remains analgesics, antibiotics, and diversion either endoscopically with stenting or with a percutaneous nephrostomy.3 Large ruptures with large perinephric or retroperitoneal urinomas require drainage percutaneously as in our case. Rarely large caliceal ruptures may require emergent surgery.

Conclusions

Obstructive ureteral stones can present with spontaneous forniceal rupture with large perinephric collections in a silent manner. Although endoscopic management alone offers excellent results in small ruptures, diversion of the collecting system with drainage of the collection remains the mainstay of treatment in large urinomas to prevent complications. Definitive management of the cause of obstruction is paramount and should be done after complete healing of the rupture.

Abbreviations Used

- CT

computed tomography

- PCNL

percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Authors' Contributions

The article was read and approved by all the authors, the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and each author believes that the article represents honest work.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: Talwar HS, Panwar VK, Mittal A, Narain TA (2020) Spontaneous large urinoma secondary to obstructing ureteral calculus: a kidney pop-off mechanism, Journal of Endourology Case Reports 6:4, 302–304, DOI: 10.1089/cren.2020.0091.

References

- 1. Chaabouni A, Binous MY, Zakhama W, Chati H, Sfaxi M, Foda M. Spontaneous calyceal rupture caused by a ureteral calculus. Afr J Urol 2013;19:191–193 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gershman B, Kulkarni N, Sahani DV, Eisner BH. Causes of renal forniceal rupture. BJU Int 2011;108:1909–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pace K, Spiteri K, German K. Spontaneous proximal ureteric rupture secondary to ureterolithiasis. J Surg Case Rep 2017;2016:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Mujalhem AG, Aziz MS, Sultan MF, Al-Maghraby AM, Al-Shazly MA. Spontaneous forniceal rupture: Can it be treated conservatively? Urol Ann 2017;9:41–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]