Abstract

Objective

Studies examining the effects of tirofiban combined with other conventional drugs for treating patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are lacking. Thus, in this study, we conducted a meta-analysis investigating both the safety and efficacy of intracoronary (IC) administration of tirofiban treatment alone versus in combination with other conventional treatments for the no-reflow phenomenon (NRP) during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with ACS.

Methods

PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Chinese Biomedical (CBM), Google Scholar, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included data comparing tirofiban treatment alone versus in combination with other conventional therapies. Two independent reviewers evaluated the quality of all data and studies were evaluated according to the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook 5.3.

Results

Thirteen RCTs involving 937 patients were included in our analysis. Tirofiban plus conventional drug treatment improved thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade 3 flow (OR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.11–0.30; p<0.01), corrected TIMI frame count (CTFC) (WMD: 6.61; 95% CI: 4.69–8.53; p<0.01), and corrected left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (WMD: −3.76; 95% CI: −4.70 to −2.82; p<0.01) and reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (OR: 3.9; 95% CI; 2.51–6.07; p<0.01). Tirofiban plus conventional therapy reduced bleeding; however, no statistical significance was observed (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.50–3.12; p=0.64).

Conclusion

IC administration of tirofiban combined with conventional drugs is more effective than tirofiban treatment alone for no-reflow (NR) during PCI without increasing bleeding events. This combination is recommended as an optimal strategy for preventing NR.

Keywords: tirofiban, no-reflow, percutaneous coronary intervention, combination therapy

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the gold standard procedure for reperfusion in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Recent studies have shown that more than 25% of blood flow to myocardial tissue is not completely restored with revascularization (1, 2). Increased myocardial perfusion sometimes occurs with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The coronary artery intimal tears may result in platelet accumulation and thrombosis, which are commonly observed in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI (3). No-reflow (NR) is an independent prognostic predictor that can develop after coronary revascularization. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPIs) are used to prevent the possibility of no-reflow. In a meta-analysis by Qin et al. (4), the safety and efficacy of the GPI tirofiban were compared with those of traditional drugs. This study showed that intracoronary (IC) administration of tirofiban is more effective in treating NR than other conventional drugs. Tirofiban inhibits platelet activation and aggregation; however, one of its major side-effects is bleeding that may cause more harm than good. Although several studies have investigated the effects of tirofiban along with other drugs for NR, information regarding the efficacy and safety in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI is lacking. In this meta-analysis, both the safety and efficiency of tirofiban alone versus in combination with conventional drugs for treating patients with STEMI undergoing PCI are evaluated.

Methods

This study was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. All analyses were conducted on the basis of previously published work. Thus, neither patients’ consent nor ethical approval was required for this study.

Search strategy

Two reviewers independently and systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, CBM, and CNKI databases for randomized trials taking place from January 2000 to January 2020 that compared tirofiban vs. tirofiban plus conventional drugs in patients with STEMI and/or ACS.

The following keywords were used: “intracoronary,” “tirofiban,” “randomized controlled trial,” “percutaneous coronary intervention,” “combined therapies,” “no-reflow (NR),” and “glycoprotein αb/βa inhibitors.” Studies written in either Chinese or English were included in our search. Letters, reviews, and non-original articles were excluded from the analyses.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (i) studies that enrolled patients with ACS or STEMI who underwent PCI; (ii) those comparing treatment with tirofiban alone to tirofiban combined with conventional drugs; (iii) reports of at least one of the following outcomes, bleeding complications, CTFC, MACE, CTFC, TIMI flow after treatment, and LVEF. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) nonrandom treatment or equivocal allocation (i.e., unclear information regarding patient allocation); (ii) PCI with thrombus aspiration for patients with severe thrombus load. A third reviewer was included to resolve any discrepancies if a consensus was not reached between the two reviewers.

Data extraction and synthesis

Only randomized studies investigating the effects of tirofiban alone compared to tirofiban combined with other conventional drugs in patients with STEMI or ACS were included in the meta-analysis. The details acquired from the studies were as follows: the last name of the first author of the publication, year of publication, age, disease, drug dose regimens, outcomes (bleeding events, CTFC, TIMI grade 3 flow, LVEF, and MACE), and intervention strategies. A third investigator (W.W.) was included if discrepancies existed between the two investigators.

Quality assessment

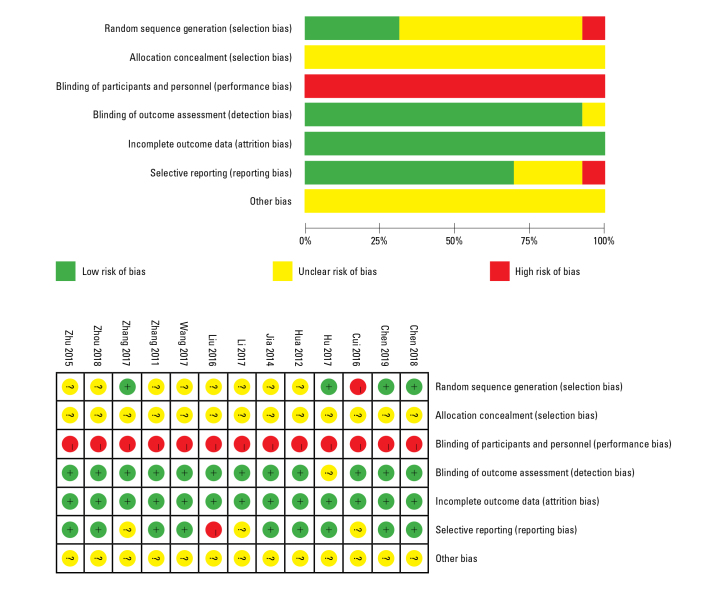

Two independent reviewers (Q.Z. and L.D.Z.) evaluated the quality of each study and assessed the risk of bias using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. Low, high, and unclear (insufficient information or uncertainty) risks of bias for each trial were evaluated (Fig. 1). A third investigator (W.W.) was included if discrepancies existed between the two investigators who performed the analyses.

Figure 1.

Assessment of bias of the studies included

Red - high risk; yellow - unclear risk; green - low risk

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014, Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as Mantel–Haenszel odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs, whereas continuous outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MDs) or standardized mean differences with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity tests were conducted using Cochran’s Q (chi-square test) and I2 statistics. A fixed-effects model was implemented unless statistical heterogeneity (p<0.10 or I2>50%) was observed. A p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search

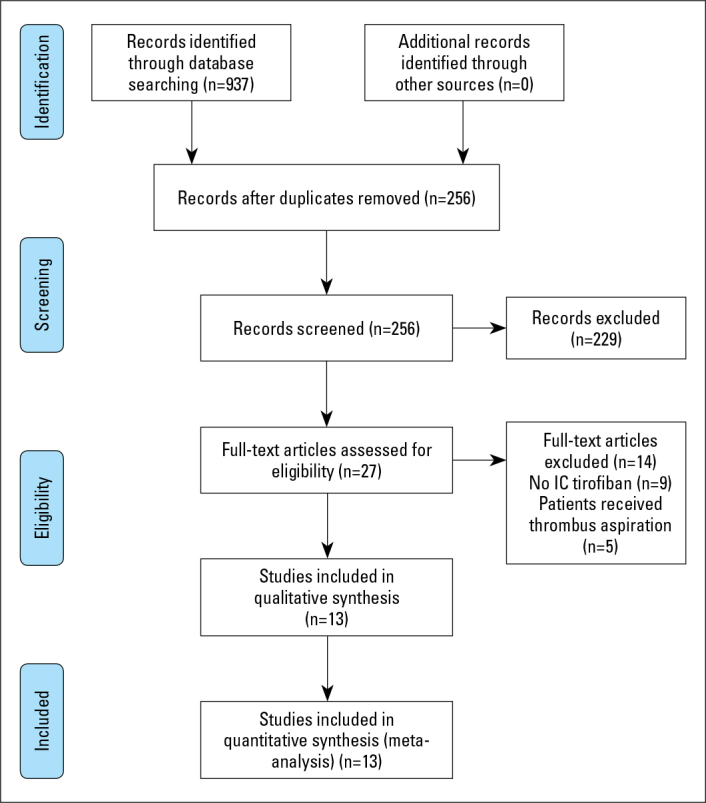

After the initial database search, 937 studies were identified. After screening the title and reading the text, duplicate results (681) were removed and 229 studies were excluded because the use of IC tirofiban was not reported (n=9) or patients were treated with thrombus aspiration (n=5). Finally, 13 Chinese language articles involving 937 patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart

Characteristics

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis. In those studies, 937 patients had STEMI or ACS and underwent PCI. The drug combination groups were as follows: 4 trials used sodium nitroprusside (5–8), 1 trial alprostadil (9), 2 trials nicorandil (10, 11), 3 trials = adenosine (12–14), and 3 trials anisodamine (15–17). Standard administration of medication was provided to all patients, including clopidogrel, aspirin, and heparin.

Table 1.

Study design of the included randomized controlled trials

| Study | Inclusion criteria | N(T/C) | Tirofiban | Combined drugs | Endpoints* | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. 2018 (5) | STEMI or ACS<12 h | 130/130 | IC 10 μg/kg within 2 mins | IC Sodium nitroprusside 200 μg within 2 mins | (1) (2) (3) (4) | 30 d |

| Wang et al. 2017 (7) | STEMI<12 h | 25/25 | IC 10 μg/kg then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 24–36 h | IC Sodium nitroprusside 200 μg | (2) (3) (4) | - |

| Hua and Fan 2012 (6) | STEMI | 41/42 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 mins | IC Sodium nitroprusside 50 μg | (2) (3) | 7 d |

| Zhang 2011 (8) | STEMI<12 h | 11/12 | IC 10 μg/kg then IV 0.115 μg/kg•min for 24 h | IC Sodium nitroprusside 200 μg | (1) (2) (3) | 7 d |

| Liu and Liu 2016 (9) | STEMI<12 h | 27/27 | IC 10 μg/kg then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 48 h | Alprostadil | (4) | 14 d |

| Li et al. 2018 (10) | STEMI<12 h | 49/49 | IC 10 μg/kg then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 48 h | IC nicorandil 0.06 μg/kg•min then IV 2 mg/h for 48 h | (3) (5) | - |

| Hu et al. 2017 (11) | ACS | 41/41 | IC 10 μg/kg then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 36 h | IC nicorandil 0.06 μg/kg•min then IV 2 mg/h for 48 h | (2) (3) (4) (5) | 14 d |

| Chen et al. 2019 (13) | STEMI<12 h | 63/63 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 min then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 24–48 h | IC adenosine 140 μg/kg•h within 6 min | (1) (3) (4) | 30 d |

| Cui et al. 2016 (14) | STEMI | 78/80 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 min then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 24 h | IC adenosine 300 μg within 1 min | (4) | - |

| Zhu and Chen 2015 (12) | STEMI | 39/39 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 min then IV 0.15 μg/kg•min for 24 h | IC adenosine 300 μg | (1) (4) | 7 d |

| Zhang 2017 (16) | STEMI<12 h | 36/36 | IC 25 μg/kg then IV 0.225 μg/kg•min for 24–48 h | IC anisodamine 1000 μg for twice, once every 2 min | (3) (4) (5) | 30 d |

| Jia 2014 (17) | STEMI<12 h | 46/48 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 min then IV 0.075 μg/kg•min for 48 h | IC anisodamine 60 μg/kg within 3 min then 0.1 μg/kg•min for 24 h | (1) (2) (3) (4) | 30 d |

| Zhou et al. 2018 (15) | STEMI | 25/25 | IC 10 μg/kg within 3 min then IV 0.075 μg/kg•min for 48 h | IC anisodamine 1500 μg for twice, 1000 μg for first one, 500 μg for second one | (1) | - |

All patients accepted dual oral antiplatelet pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin. Endpoints*: (1) transformation of TIMI flow, (2) CTFC, (3) MACE, (4) LVEF, and (5) bleeding events.

TIMI - thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; CTFC - corrected TIMI frame count; MACE - major adverse cardiovascular events; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction; IC - intracoronary

Quantitative synthesis

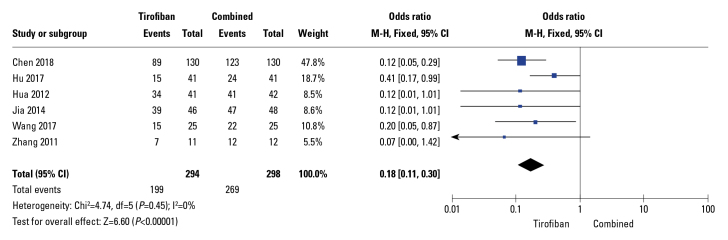

Following PCI, six trials reported a TIMI flow of grade 3. No heterogeneity was observed between the studies (I2=0%). Compared to tirofiban alone, traditional drugs combined with tirofiban significantly increased TIMI grade (OR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.11–0.3; p<0. 01; I2=0%) after PCI based on the fixed-effects model (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots comparing thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow transformation

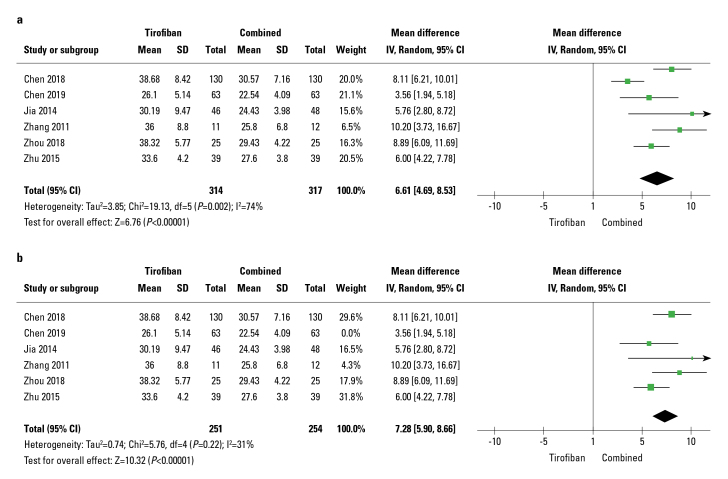

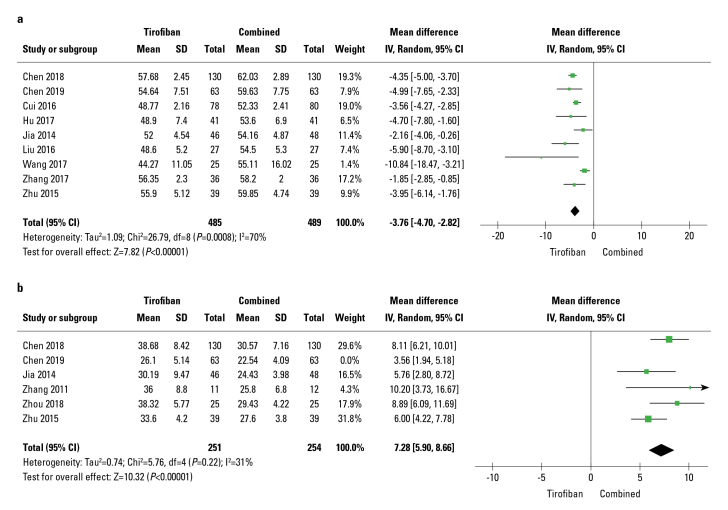

Out of 13 studies, six studies reported CTFC. The random-effects model was implemented since significant heterogeneity existed in these RCTs (I2=74%). Tirofiban combined with the traditional drug treatment group significantly reduced CTFC (WMD: −6.61; 95% CI: 4.69–8.53; p<0.01; I2=74%) (Fig. 4a). Sensitivity analyses were conducted after removing a study conducted by Chen, 2019, which reduced heterogeneity (I2) from 74% to 31% and the pooled MD from 6.61 (4.69, 8.53) (p<0.01, Fig. 4a) to 7.28 (5.90, 8.66) (p<0.01, Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Forest plots comparing corrected TIMI frame count

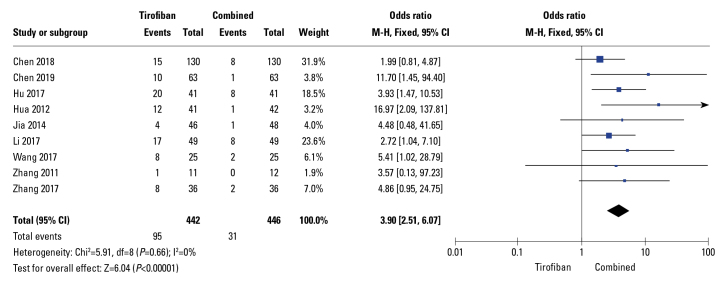

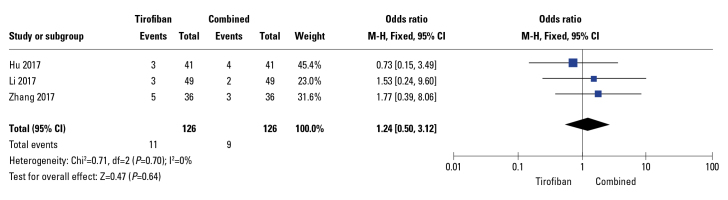

Moreover, the rate of MACE was significantly reduced in drug combination groups (OR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.11–0.30; p<0.01; I2=0%; Fig. 5) in 6 out of 13 studies. Additionally, in these RCTs, the rate of LVEF was significantly increased in the drug combination group compared to that in compared to tirofiban-alone group (WMD: −3.76; 95% CI: −4.70 to −2.82; p<0.01) with relatively high heterogeneity (I2=70%), as demonstrated by the random-effects meta-analysis (Fig. 6a). Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding a study by Zhang (16); as a result, heterogeneity (I2) decreased from 70% to 40% and the pooled MD from −3.76 (−4.70, −2.82) (p<0.01, Fig. 6a) to −4.05 (−4.80, −3.30) (p<0.01, Fig. 6b); in terms of heterogeneity, these results were in line with those reported in a trial performed by Zhang, 2017. Three studies reported bleeding events; however, the differences between groups were not significant (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.5–3.12; p=0.64, Fig. 7) and no signs of heterogeneity were observed (I2=0%).

Figure 5.

Forest plots comparing major adverse cardiovascular events

Figure 6.

Forest plots comparing left ventricular ejection fraction

Figure 7.

Forest plots comparing bleeding events

Assessment of publication bias

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.3.0, a funnel plot was not used to evaluate publication bias, since fewer than 10 articles were available for quantitative analysis.

Discussion

PCI restores blood perfusion and supply in the coronary artery. However, after PCI, individuals are vulnerable to NR (18). No-reflow phenomenon (NRP) is associated with poor prognosis, including a higher incidence of postinfarction complications, poor ventricular remodeling, delayed and repeated hospitalization for heart failure, and a higher mortality rate, limiting the benefits of PCI. Myocardial damage may result from atheromatous plaque, especially that caused by large debris (> 200 μm in diameter), which may contribute to NRP. Myocardial blush grade (MBG), TIMI, myocardial perfusion grade (MPG), CTFC, electrocardiogram (ECG), and magnetic resonance imaging were used to analyze microvascular obstructions after reperfusion in catheterization laboratories. Rapid recovery of myocardial perfusion is essential for treating NR, which occurs by clearing microvascular occlusions and restoring flow in occluded vessels (19).

Thrombus aspiration and GPI tirofiban administration are important adjunctive treatment strategies for the infarct-related artery during primary PCI for STEMI. High thrombus load is an independent predictor of mortality and is more likely to lead to distal embolism. Svilaas et al. (20) reported that thrombus aspiration considerably reduced mortality and improved myocardial perfusion. However, in a recent meta-analysis, Elgendy et al. (21) highlighted routine thrombus aspiration was not beneficial; thus, it was not recommended according to the guidelines by ESC and ACC/AHA (22, 23). Previous RCTs and meta-analyses have reported that, in patients with ACS, IC administration of GPI resulted in greater blood flow restoration and a better prognosis postoperatively than IV (intravenous) administration. Besides, IC administration did not lead to increased bleeding events, which are commonly observed with IV administration (24–29). Sun et al. (30) demonstrated that IC administration did not provide optimal contact between GPIs and lesions in patients with ACS during PCI. Instead, intralesional (IL) drug administration achieved higher local drug concentration and offered a superior option.

GPIs may reduce ischemic events by reducing thrombus formation and/or restoring blood flow in an obstructed vessel (31, 32). The use of enhanced antiplatelet therapy reduces thromboembolism, restores coronary blood flow, and enhances myocardial tissue perfusion. Currently, distal intracoronary administration of various conventional drugs, such as calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem, and nicardipine), adenosine, sodium nitroprusside, and anisodamine can be used as a form of vasodilation therapy to reverse NR. Conventional drugs improve coronary flow and myocardial perfusion. However, these drugs cannot inhibit thrombi resulting from accumulated platelets, limiting their efficacy.

IC administration of conventional drugs combined with tirofiban is more effective in preventing NR than the administration of tirofiban alone. Consistent with the pharmacological mechanism, compared to tirofiban alone, tirofiban combined with conventional drugs significantly increased TIMI flow and significantly reduced CTFC during PCI in patients with ACS. Both CTFC and TIMI flow grade 3 (TFG3) are used to assess epicardial blood flow (33). Compared to TFG3, CTFC has a prognostic accuracy when predicting the survival rate and improvement in epicardial flow with reperfusion (33–35). TMPG and myocardial perfusion can be used to predict mortality relevant to epicardial flow in patients with STEMI (36).

A lower heterogeneity (I2) of LVEF from 70% to 40% resulted from removing Zhang’s study, 2017 (25 μg/kg IC tirofiban, then 0.225 μg/kg•min IV tirofiban for 24 h–48 h beyond the standard dose, and then 10 μg/kg IC tirofiban within 3 min, followed by 0.15 μg/kg•min IV tirofiban for 24 h). This regimen resulted in greater inhibition of platelets and quicker action compared to standard bolus regimens because the trial was testing tirofiban at a higher bolus dose (37–39). The remaining heterogeneity after removing Zhang’s (16) 2017 study could be due to various clinical settings and/or different tirofiban regimens tested in different studies. Clinical observation of NRP has been extensively reported (40), and its occurrence after PCI is an adverse prognostic sign (41) related to decreased LVEF and adverse left ventricular remodeling.

Elevated MACE in patients with ACS who underwent PCI is related to impaired TIMI blood flow or myocardial reperfusion (42, 43). In line with these results, our meta-analysis showed that the IC administration of tirofiban along with conventional drugs reduced MACE in patients with ACS.

The clinical benefits can be impeded by bleeding associated with reinforced antiplatelet inhibition. All patients enrolled in this study were given dual oral antiplatelet treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin preoperatively and conventional vasodilator drugs were administered to the combination group. No statistical differences between the two groups in terms of bleeding were observed (p>0.05); however, an increased bleeding trend was noted in the patients’ group treated with tirofiban alone (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.5–3.12; p=0.64). Various studies have reported that PCI negatively affects the fibrinolytic system in patients with either stable or unstable coronary artery disease. This may be related to the finding that vasodilators improve the fibrinolytic system. Moreover, Zhang’s (16) study was included in this meta-analysis where 25 ug/kg of tirofiban was used, which closely mimicked abciximab-driven platelet inhibition. The inhibitory effect of tirofiban at a higher dose on platelet activity was significantly increased compared with the standard injection regimen of 10 ug/kg (44). Thrombocytopenia has been linked to bleeding complications (45, 46). Given the same dosage and duration, treatment methods are not expected to affect bleeding risk.

In this study, there are several strengths associated with the conducted analyses as follows. First, this is the first meta-analysis that directly compares the IC administration of tirofiban alone with its combination with other conventional drugs used for treating patients with ACS who underwent PCI. Second, this study was conducted following PRISMA guidelines for literature retrieval, the inclusivity of articles, and data synthesis (47). Third, the Cochrane Collaboration tool was used to access the risk of bias. Finally, the heterogeneity was evaluated using a random-effects model. Altogether, these strengths ensure that the quality of the analyses performed in this study is reliable.

Despite these strengths, several limitations were noted during this study. First, we did not evaluate whether conventional drugs could improve myocardial perfusion with other dosing regimens and the costs of different strategies were not calculated. Second, we only studied GPI tirofiban and did not investigate other GPIs, such as abciximab or eptifibatide, and whether they had an optimal impact on myocardial perfusion. However, a study performed by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) (48) showed no significant differences between the GPI tirofiban and eptifibatide or abciximab in terms of safety and efficacy. Finally, there was a potential for publication and selection biases. In the future, multicenter larger samples and double-blind RCTs are warranted to provide greater evidence.

Conclusion

IC administration of tirofiban combined with conventional drugs can effectively improve coronary blood flow and myocardial perfusion, increase LVEF, and reduce MACE, without increasing major bleeding events after PCI in patients with ACS compared to administration of tirofiban alone. Thus, tirofiban combined with other conventional therapies is recommended as a valid option to prevent NR.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81560318, and 81860346); Training Project of “139” Program for High-level Medical Talents in Guangxi (No. G201903034); and Guangxi Medical and Health Suitable Technology Development Project (No. S2017021). The funders had no role in study design, nor in the data collection and analysis, nor in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – Q.Z.; Design – Q.Z.; Supervision – W.W.; Fundings – W.W.; Materials – Q.Z.; Data collection &/or processing – Q.Z., L.D.Z.; Analysis &/or interpretation – Q.Z.; Literature search – L.D.Z.; Writing – Q.Z.; Critical review – L.D.Z., W.W.

References

- 1.Maekawa Y, Asakura Y, Anzai T, Ishikawa S, Okabe T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Relation of stent overexpansion to the angiographic no-reflow phenomenon in intravascular ultrasound-guided stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2005;20:13–8. doi: 10.1007/s00380-004-0798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka A, Kawarabayashi T, Nishibori Y, Sano T, Nishida Y, Fukuda D, et al. No-reflow phenomenon and lesion morphology in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:2148–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015697.59592.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baber U, Mehran R, Giustino G, Cohen DJ, Henry TD, Sartori S, et al. Coronary Thrombosis and Major Bleeding After PCI With Drug-Eluting Stents: Risk Scores From PARIS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2224–34. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000015697.59592.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin T, Xie L, Chen MH. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of intracoronary administration of tirofiban for no-reflow phenomenon. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen ZJ, Huang XX, Li ZQ. Efficacy of tirofiban combined with sodium nitroprusside in the treatment of no-reflow phenomenon during emergency PCI. J Hunan Normal Univ (Med Sci) 2018;15:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua PD, Fan LY. Observation on the effect of tirofiban combined with sodium nitroprusside in the treatment of no reflow of coronary artery. Chin Community Doctors. 2012;14:42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CQ, Shi Bing, Chen JX. Observation on the Effect of Sodium Nitroprusside Combined with Tirofiban for the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction Without Reflow Phenomenon of Coronary Artery After Emergency PCI. Clinical Medicine&Engineering. 2017;24:501–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang CJ. Effect of Nitroprusside on No-reflow in Interventional Treatment of Myocardial Infarction. Medical Information. 2011;24:86–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Liu XF. The application value of tirofiban combined with alprostadil in the treatment of STEMI patients with PCI. Chinese Journal of Clinical Research. 2016;29:1657–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Ming, Zhang YL, Lai JC, Zheng Wei, Tan Gang, Yang XY. Clinical trial of tirofiban injection combined with nicorandil injection in the treatment of acute anterior wall ST elevation myocardial infarction. Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34:1491–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiang H, Liu HY, Dong L, Pan GZ, Liang CL, Huang MZ. The preventive effect of Nicorandil combined with Tirofiban on no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Practical J of Cardiac Cerebral Pneumal and Vascular Disease (PJCCPVD) 2017;25:146–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu XF, Bo C. Effects of tirofiban combined with adenosine on myocardial microcirculation and cardiac function in elderly patients with STEMI during perioperative of percutaneous coronary intervention. Chinese Journal of Gerontology. 2015;15:4219–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao C, Zhiyuan Z, Ming Y, Tianlong W. The protective effect of adenosine combined with tirofiban on reperfusion injury and cardiac function after PCI in elderly patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Chinese and Western Medicine Combined Cardio-Cerebrovascular Disease Journal. 2019;17:2803–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui FS, Liu YN, Wang XQ. The protective effect of adenosine combined with tirofiban on reperfusion injury and cardiac function in elderly patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction after PCI. Med J of Chin People’s Health. 2016;28:37–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shu Z, Bu FQ, Li SX, Yan W. Effects of tirofiban alone and anisodamine in combination on no reflow after PCI in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Practical Clinical Medicine. 2018;18:12–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang F. Effects of application combined with tirofiban and anisodamine on primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Anhui Medical and Pharm J. 2017;21:1501–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia HY. Effect and Safety of Intracoronary Administration of Anisodamine and Tirofiban on Myocardial Perfusion in Patients with Acute ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Hebei: Hebei Medical University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimonaga T, Kurisu S, Watanabe N, Ikenaga H, Higaki T, Iwasaki T, et al. Myocardial Injury after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for In-Stent Restenosis Versus de novo Stenosis. Intern Med. 2015;54:2299–305. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CH, Wong HB, Tan HC, Zhang JJ, Teo SG, Ong HY, et al. Impact of reversibility of no reflow phenomenon on 30-day mortality following percutaneous revascularization for acute myocardial infarction-insights from a 1,328 patient registry. J Interv Cardiol. 2005;18:261–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2005.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, Diercks GF, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:557–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elgendy AY, Elgendy IY, Mahmoud AN, Bavry AA. Long-term outcomes with aspiration thrombectomy for patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:534–41. doi: 10.1002/clc.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Kardiol Pol. 2018;76:229–313. doi: 10.5603/KP.2018.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali-Hasan-Al-Saegh S, Mirhosseini SJ, Shahidzadeh A, Rahimizadeh E, Sarrafan-Chaharsoughi Z, Ghodratipour Z, et al. Appropriate bolus administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: intracoronary or intravenous? A comprehensive and updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Kardiol Pol. 2016;74:104–18. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Wu B, Shu X. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing intracoronary and intravenous administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedland S, Eisenberg MJ, Shimony A. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of intracoronary versus intravenous administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu YL, Kampinga MA, Wieringa WG, Fokkema ML, Nijsten MW, Hillege HL, et al. Intracoronary versus intravenous administration of abciximab in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention with thrombus aspiration: the comparison of intracoronary versus intravenous abciximab administration during emergency reperfusion of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (CICERO) trial. Circulation. 2010;122:2709–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.002741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiele H, Schindler K, Friedenberger J, Eitel I, Fürnau G, Grebe E, et al. Intracoronary compared with intravenous bolus abciximab application in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the randomized Leipzig immediate percutaneous coronary intervention abciximab IV versus IC in ST-elevation myocardial infarction trial. Circulation. 2008;118:49–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.747642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang X, Li R, Jing Q, Liu Y, Liu P. Efficacy and Safety of Intracoronary versus Intravenous Administration of Tirofiban during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun B, Liu Z, Yin H, Wang T, Chen T, Yang S, et al. Intralesional versus intracoronary administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8223. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topol EJ, Byzova TV, Plow EF. Platelet GPIIb-IIIa blockers. Lancet. 1999;353:227–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warnholtz A, Ostad MA, Heitzer T, Goldmann BU, Nowak G, Munzel T. Effect of tirofiban on percutaneous coronary intervention-induced endothelial dysfunction in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:20–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeRouen TA, Murray JA, Owen W. Variability in the analysis of coronary arteriograms. Circulation. 1977;55:324–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.55.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamada S, Nishiue T, Nakamura S, Sugiura T, Kamihata H, Miyoshi H, et al. TIMI frame count immediately after primary coronary angioplasty as a predictor of functional recovery in patients with TIMI 3 reperfused acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:666–71. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Daley WL, Dodge JT, Jr, Alexander B, Jr, Marble SJ, et al. TIMI frame count: a quantitative method of assessing coronary artery flow. Circulation. 1996;93:879–88. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Marble SJ, Barron HV, Braunwald E TIMI Study Group. Relationship of the TIMI myocardial perfusion grades, flow grades, frame count, and percutaneous coronary intervention to long-term outcomes after thrombolytic administration in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:1909–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000014683.52177.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batchelor WB, Tolleson TR, Huang Y, Larsen RL, Mantell RM, Dillard P, et al. Randomized COMparison of platelet inhibition with abciximab, tiRofiban and eptifibatide during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes: the COMPARE trial. Comparison Of Measurements of Platelet aggregation with Aggrastat, Reopro, and Eptifibatide. Circulation. 2002;106:1470–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000029744.01096.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabbani SS, Aggarwal A, Terrien EF, DiBattiste PM, Sobel BE, Schneider DJ. Suboptimal early inhibition of platelets by treatment with tirofiban and implications for coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:647–50. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider DJ, Herrmann HC, Lakkis N, Aguirre F, Lo MW, Yin KC, et al. Increased concentrations of tirofiban in blood and their correlation with inhibition of platelet aggregation after greater bolus doses of tirofiban. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:334–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)03163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kloner RA. No-reflow phenomenon: maintaining vascular integrity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:244–50. doi: 10.1177/1074248411405990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rezkalla SH, Stankowski RV, Hanna J, Kloner RA. Management of No-Reflow Phenomenon in the Catheterization Laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, van ‘t Hof AW, de Boer MJ, Dambrink JH, Gosselink M, et al. Angiographic assessment of reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction by myocardial blush grade. Circulation. 2003;107:2115–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065221.06430.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porto I, Hamilton-Craig C, Brancati M, Burzotta F, Galiuto L, Crea F. Angiographic assessment of microvascular perfusion--myocardial blush in clinical practice. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1015–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sethi A, Bahekar A, Doshi H, Bhuriya R, Bedi U, Singh S, et al. Tirofiban use with clopidogrel and aspirin decreases adverse cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:548–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merlini PA, Rossi M, Menozzi A, Buratti S, Brennan DM, Moliterno DJ, et al. Thrombocytopenia caused by abciximab or tirofiban and its association with clinical outcome in patients undergoing coronary stenting. Circulation. 2004;109:2203–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127867.41621.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McClure MW, Berkowitz SD, Sparapani R, Tuttle R, Kleiman NS, Berdan LG, et al. Clinical significance of thrombocytopenia during a non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. The platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in unstable angina: receptor suppression using integrilin therapy (PURSUIT) trial experience. Circulation. 1999;99:2892–900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gurm HS, Tamhane U, Meier P, Grossman PM, Chetcuti S, Bates ER. A comparison of abciximab and small-molecule glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of contemporary randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:230–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.847996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]