Highlights

-

•

Mechanism of laser cavitation peening (LCP) was investigated.

-

•

Understanding into the dynamic characteristics of cavitation bubble in LCP.

-

•

Q235 steel was impacted by LCP and the strengthening mechanism was analyzed.

-

•

Degradation of Methylene blue solution by LCP was discussed.

Keywords: Laser cavitation peening, Bubble dynamic characteristic, Material strengthening, Chemical effect

Abstract

The mechanism of laser cavitation peening (LCP) including laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet was investigated at various stand-off distances combined with experiment and simulation. The dynamic characteristics, pressure field, and temperature field of cavitation bubble were investigated. The Q235 steel was impacted by LCP and the strengthening mechanism was analyzed, and the chemical effect in LCP was discussed. The results found that the pressure intensity of shock wave and water-jet decreases with increasing the . At , the laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet are 989 Mpa, 763 Mpa, and 369 Mpa respectively. The pressure and temperature of the bubble decrease obviously in the second and third pulsations. The impact of LCP causes plastic deformation on the Q235 steel surface and refines the grains on the surface layer within a depth of 20–30 μm. The enhancement of microhardness and the residual stress increases with the increase of , and the optimal value for LCPwc is 0.4. The degradation rate of MB solution in the infinite domain, LCPwc, and LCP is 26.4%, 41.7%, and 34.5%.

1. Introduction

Cavitation is a unique phenomenon involving the process of formation, growth, and collapse of the bubble in a liquid medium [1], [2], [3]. The initial understanding of cavitation originates from the damage of materials caused by the produced large impact when cavitation bubbles collapse, i.e., cavitation erosion [4], [5]. However, cavitation also can be applied in many fields if the impacts of shock wave and water-jet are employed properly. Recently, some scholars have begun to take advantage of the huge energy released by the shock wave and water-jet during the stage of bubble collapse, such as surface cleaning [6], [7], drug delivery [8], shock wave lithotripsy [9], and cavitation strengthening [10], [11].

Among various methods of generating cavitation (acoustic cavitation, hydrodynamic cavitation, optical cavitation, and particle cavitation) [12], laser cavitation has attracted much attention due to its high flexibility and maneuverability. When the laser beam is focused on the liquid, the water will be penetrated and thereby form a plasma if the energy density of the laser exceeds the breakdown threshold of the liquid medium. Then the plasma continues to absorb the laser energy and expands to a cavitation bubble, which experiences the cyclical pulsation of “expansion-contraction”. Recently, there have been some efforts to investigate the effect of cavitation using the method of laser cavitation. Liu et al. [13] used a liquid-jet produced by the collapse of a laser-induced bubble to investigate the effect of cavitation on the copper target. The results indicated that the liquid-jet impact is the main damage mechanism in cavitation erosion. Ren et al. [14] studied the mechanical property of 2A02 aluminum alloys treated by laser-induced cavitation bubbles and discussed the strengthening mechanisms of cavitation bubbles. Gu et al. [15] employed laser cavitation to degrade the Rhodamine B solution under various laser energies. The energy consumption in the process of laser cavitation was discussed and the possible degradation mechanism was proposed. Zhang et al. [16] used a high-speed camera to study the collapsing dynamics of a laser-induced cavitation bubble near the edge of a rigid wall. It was found that the bubble would gradually approach the edge in the pulsation, and the generation distance of the bubble had a great influence on the bubble evolution. However, there few attention to the novel technology of laser cavitation peening (LCP). LCP is a complex process with many characteristics including physical and chemical aspects. The mechanism of bubble evolution, material strengthening, and chemical effect in the process of LCP needs to be investigated systematically.

In this study, the combination method of experiment and simulation was adopted to study LCP. The mechanism of the laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet was revealed. The dynamic characteristics of laser-induced cavitation bubble at various stand-off distances during the process of LCP were analyzed. The strengthening of Q235 steel treated by LCP and the chemical effect in LCP were discussed.

2. Experiment and simulation

2.1. Materials preparation

Q235 steel with the dimension of 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm (length × width × height) was adopted as the specimen. Table. 1 and Table. 2 show the chemical compositions and the mechanical properties of Q235, respectively. Before LCP processing, all specimens were polished with abrasive paper. The 0.04 mm thick aluminum foil was pasted on the polished surface of the specimen as a coverage layer. Methylene blue (MB, C16H18ClN3S, 319.85 g·mol−1, analytical reagent grade) solution was prepared by deionized water, and the concentration was 10 mg/L.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of Q235 steel (wt %).

| C | Si | Mn | S | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.35–0.80 | 0.50 | 0.45 |

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of Q235 steel.

| Mechanical properties | Tensile Strength σb (MPa) | Yield Strength σ0.2 (MPa) | Elongation δ5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q235 steel | 375–460 | 235 | 26 |

2.2. Experimental setup and procedure

The schematic diagram of LCP experimental system is presented in Fig. 1. The laser beam was generated by an Nd:YAG nanosecond laser and was focused by a lens system. The wavelength and pulse width of the laser were 1064 nm and 8 ns. The laser energy and pulse frequency used in the study were 200 mJ and 1 Hz, respectively. The lens system included a concave lens, two convex lenses and a reflect lens, which was employed to adjust the laser energy density to avoid the strip optical breakdown and the dispersion of laser energy. The focused laser beam impacted the specimen surface and generated a hemispherical cavitation bubble attaching to the specimen surface. In the process of LCP, the dynamic evolution of the cavitation bubble was recorded by the high-speed camera, and a laser light source was adopted as a backlight. The acoustic signals of laser breakdown and bubble collapse were detected by a hydrophone. The scanning path of LCP was set with a “Z”-shaped road map, and the velocity of three-dimensional in X and Y axis were 250 μm/s. For the convenience of the study, a non-dimensional parameter is defined as

| = H/Rmax | (1) |

where H is the distance between the laser focus and the rigid wall (defocusing amount), Rmax is the maximum radius of cavitation bubble.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of LCP Experimental system.

2.3. Material and chemical measurement

An ultrahigh-resolution true color confocal microscope (Axio CSM 700) was employed to measure the surface morphology and roughness of Q235 specimens after LCP treatment. An X-350A stress tester was used to measure the residual stress of specimens with the method of X-ray diffraction. The diffraction crystal plane was (2 1 1) and the scanning angle was from 151° to 162°. The microhardness of the specimen was measured by an HV-1000 Vickers tester, and a standard Knoop indenter with a loading load of 1.96 N was adopted. The microstructure of the Q235 specimen was observed by an optical microscope. Before the observation, the cross section of the specimen was etched by a chemical reagent of 4 mL HNO3 and 96 mL C2H5OH. The ultraviolet spectrophotometer was employed to detect the concentration of MB solution according to the absorbance change of MB at the maximum absorption wavelength of 664 nm. The liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was used to detect the degradation products of MB after LCP.

2.4. Method and process of simulation

The dynamic evolution, pressure field, temperature field, and flow field of cavitation bubble were simulated by Fluent software. In the numerical simulation, the VOF method was adopted and the liquid around the cavitation bubble was assumed incompressible. The mass transfer between the liquid and the gas was ignored, and the ideal-gas was filled inside the bubble. The impact of the water-jet on the steel and the evolution of the water-jet were simulated by AutoDyn software. The velocity of the water-jet during the bubble collapse was obtained from the calculation results of Fluent, and these results were used to the initial condition of AutoDyn. The surface deformation and the residual stress distribution of material under various LCP impacts were simulated by Abaqus software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. LCP mechanism

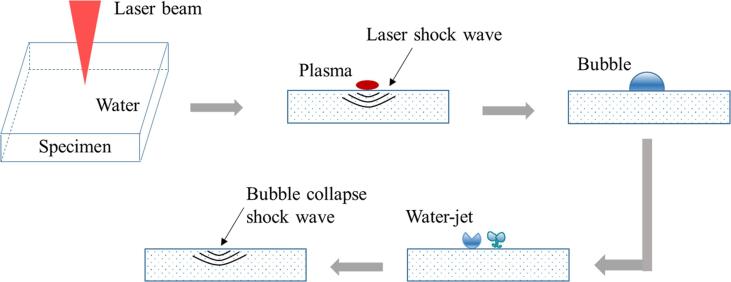

3.1.1. Process of LCP

In laser shock peening (LSP), as the laser beam is focused on the material surface, the metal absorbs laser energy and the plasma shock wave forms [17], [18]. Shock wave and water-jet generate in cavitation peening (CP) originates from the collapse of the cavitation bubble [19], [20], [21]. In comparison, the mechanism of LCP is more complicated, which combines the LSP and CP. The process of the LCP includes the impact of laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet, as shown in Fig. 2. When the laser is incident into the water, a part of laser energy is consumed and the water is broken down to form a plasma. There is a lot of laser energy directly acting on the specimen surface, and the remaining laser energy is dissipated in the water. At this moment, the laser shock wave impacts the specimen surface. Then the collapse of the bubble results in the generation of the shock wave and water-jet, which impact the specimen surface again. Due to a large quantity of laser energy and bubble energy is consumed in the stage of laser breakdown and bubble first pulsation, the impacts of the shock wave as well as water-jet generated at the second and third collapse of the bubble are weak and can be ignored.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the process of LCP impact.

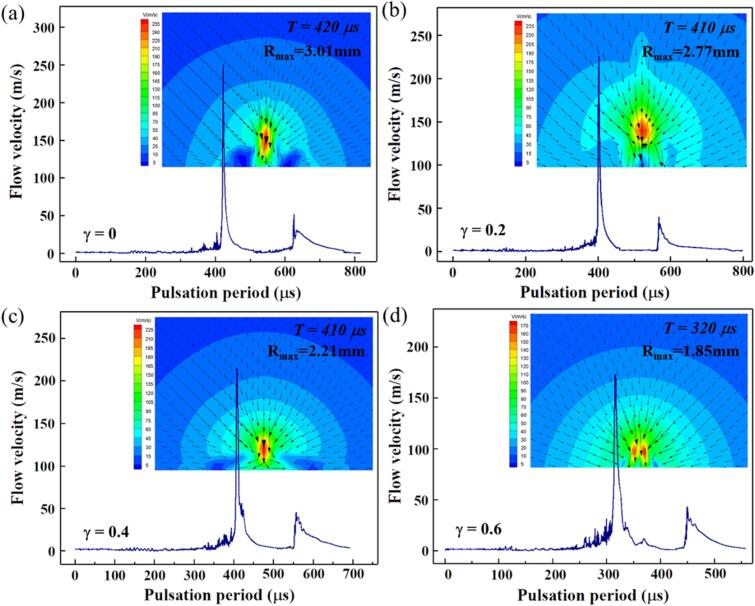

3.1.2. Shock wave

The laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave in LCP impact were detected by a hydrophone. Fig. 3 shows the acoustic signals and bubble evolution at various . It can be seen that there are two main peaks, and these two peaks represent the signal of the laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave, respectively [22]. There are also lots of small peaks in the acoustic signal, which can be considered as the noise in the liquid environment and the influence can be ignored. The pressure of the shock wave can be calculated by equation (2). The hydrophone is set as a 45-degree angle to the specimen surface and the distance is 5 mm. The values of the laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave are presented in Fig. 4. The maximum pressure of laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave occurs in , which reaches 989 Mpa and 763 Mpa. As the increase of, the detected pressure decreases significantly, which indicates the impact intensity of the shock wave is weakened. As we know, the maximum value of energy is in the focus of laser. The laser energy on the Q235 specimen attenuates with the increase of defocusing amount, so the pressure of laser shock wave impacting on the specimen decreases significantly. Additionally, the pressure of the bubble collapse shock wave is always smaller than the laser shock wave, accounting for about two-thirds. The variation trend of shock wave pressure corresponds to the pulsation of bubble. The bubble radius and pulsation period of bubble decrease with the increase of, and the phenomenon of multi-point breakdown occurs whenexceeds 0.4.

| (2) |

where P is the pressure of shock wave, Vm is the voltage and n1 is the sensitivity of the hydrophone (n1 = 10 nV/Pa).

Fig. 3.

Acoustic signal and bubble evolution in LCP impact at various non-dimensional parameter. (a) , (b) 0.2, (c) 0.4, (d) 0.6.

Fig. 4.

The value of laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave.

The Q235 specimen and the liquid near the focal point absorb the laser energy and the plasma generates. The plasma expands at supersonic speed and continuously compresses the surrounding liquid medium, which results in the formation of a laser shock wave. The shock wave quickly attenuates into a sound wave after spreading a certain distance. A similar study was performed by Brujan [23], and the lower laser energy was used to induce cavitation bubbles in water. The values of shock wave emission during the optical breakdown at 1 mJ and 10 mJ laser energy are 0.7 Mpa and 2.64 Mpa, respectively. Moreover, the shock wave was also detected during the collapse of the ultrasound-induced cavitation bubble [24]. When a PVDF hydrophone was placed 10 mm from the emission center, the detected shock wave emission during bubble collapse was from 0.122 MPa to 0.162 Mpa in the range of γ = 1.2–1.55. The shock wave will attenuate during its propagation, and the pressure value emitted by the shock wave is related to the propagation distance r. Ref. [25] reported that the maximum shock pressure at 68 μm from the bubble wall is 1.3 ± 0.3 GPa. The shock pressure decays proportionally to r−1.5 with increasing distance from the bubble. In LCP, the pressure of the laser shock wave is affected by liquid depth, viscosity, tension, and temperature. Ni et al. [26] considered that the waveform, amplitude, and period of the plasma acoustic wave are different if the materials exposed to laser radiation are different. Ref. [27] reported that the propagation speed of shock wave can reach 5.4 km/s and the peak pressure shock wave can achieve 11.8 GPa. Bubble energy reflects the intensity bubble collapse shock wave, which mainly focuses on the first pulsation, so the shock wave in the next pulsations can be ignored. Yang et al. [28] thought the bubble radius decreases 30% in the second pulsation and the bubble energy only a third remains.

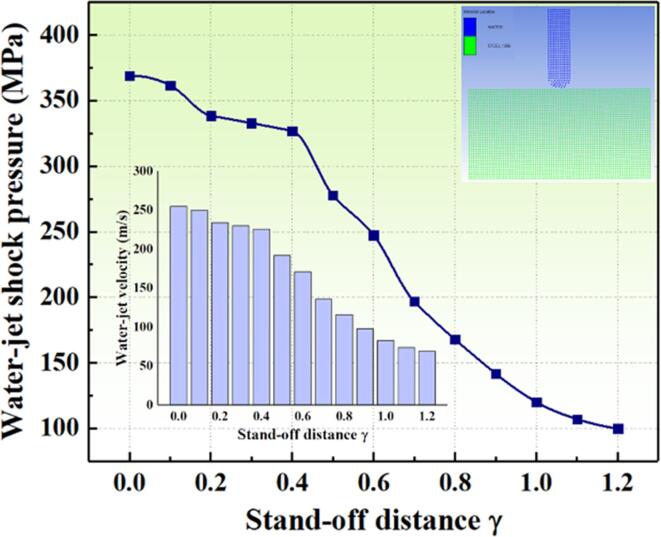

3.1.3. Water-jet

Water-jet is a peculiar phenomenon that only generates when the cavitation bubble is near the wall. The liquid is imbalanced in the momentum of the vertical solid boundary due to the restriction of the wall and thereby generating a high-speed jet on the vertical solid boundary [29]. Fig. 5 displays the simulation of water-jet velocity and the flow field distribution in the bubble pulsation. It can be seen that the flow velocity is almost zero during the bubble pulsation. At the end of the bubble collapse, the water-jet gradually generates and the velocity reaches the maximum value. Due to the bubble energy is lower at large , the flow velocity decreases with the increase of . The flow velocity under four kinds of are 255 m/s, 234 m/s, 226 m/s and 171 m/s. Then the velocity rapidly decreases to 0 m/s as the second pulsation of bubble begins. During the second period of the bubble collapse, the velocity of the water-jet decreases significantly, leaving only about 50 m/s. Most of the bubble energy is converted into acoustic energy during the first pulsation process, and the loss of bubble energy can reach up to 60% [30]. There is also an energy threshold for the generation of water-jet, so it is difficult to generate the water-jet in the third period of bubble collapse [31]. As can be seen in the vector cloud diagram of the flow field, the velocity field of the water-jet appears in the shape of a layered mushroom cloud near the top of the rigid wall. Water-jet penetrates the bubbles from the left and right sides and concentrates in the middle, which shoots towards the rigid wall. The maximum velocity of the water-jet appears above the boundary and shoots perpendicularly to the wall, and it diverges to both sides of the boundary as time goes by.

Fig. 5.

Velocity of water-jet and flow field distribution in the bubble pulsation.

The impact pressure of the water-jet on a rigid wall can be calculated by a water hammer pressure Eq. (3) [32]. Vogel [33] reported that when the velocity of the water-jet reaches 100 m/s, the corresponding water hammer pressure is about 450 MPa. Fig. 6 presents the velocity and the shock pressure of water-jet at various, and the operating environment of LCP is room temperature (ρ1 = 1000 kg/m3 and C1 = 1496 m/s, ρ2 = 7850 kg/m3 and C2 = 5918 m/s). The corresponding maximum radius of the cavitation bubble is listed in Table. 3. At = 0, the velocity of water-jet is 255 m/s, and the corresponding shock pressure is 368.94 Mpa. At the range of = 0 to 0.4, the decrease of shock pressure is not very obvious, and the pressure at = 0.4 is 326.98 Mpa. The bubble energy is seriously consumed due to the multi-point breakdown of the laser whenexceeds 0.4, so the shock pressure of the water-jet is greatly weakened. The shock pressure is only 120.09 Mpa at = 1. The lower pressure of water-jet impact is less than the yield strength of Q235, which cannot cause the surface plastic deformation of Q235. Asexceeds 1, the bubble can be considered as expanding and collapsing in the infinite domain, so the shock pressure tends to be steady. Fig. 7 shows the simulation of the impact process of water-jet on steel at 255 m/s. Different from the transient impact of the shock waves, the impact of water-jet is a continuous process. Firstly, a water-jet impinges on a point on the steel surface, and the maximum pressure of water-jet impact occurs on both sides of the water-jet but not in the center (see Fig. 7(a) and (b)). In Fig. 7(c), the water-jet spreads out on both sides of the steel surface and the impact pressure decreases significantly, while the peak value is still on both sides of the water-jet. Moreover, the shock pressure impacting on steel surface decreases with the divergence of jet flow.

| (3) |

where P is the pressure generated by the water-jet impacting onto the wall, ρ1 and C1 are the density and sound velocity of water, ρ2 and C2 are the density and sound velocity of the Q235 steel.

Fig. 6.

Velocity and shock pressure of water-jet at various.

Table 3.

Bubble maximum radius at various corresponding to the water-jet.

| γ | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rmax | 3.01 | 2.95 | 2.77 | 2.57 | 2.21 | 1.98 | 1.85 | 1.68 | 1.57 | 1.42 | 1.33 | 1.22 | 1.15 |

Fig. 7.

Simulation of the process of the impact of water-jet on steel at γ = 0 and Rmax = 3.01 mm.

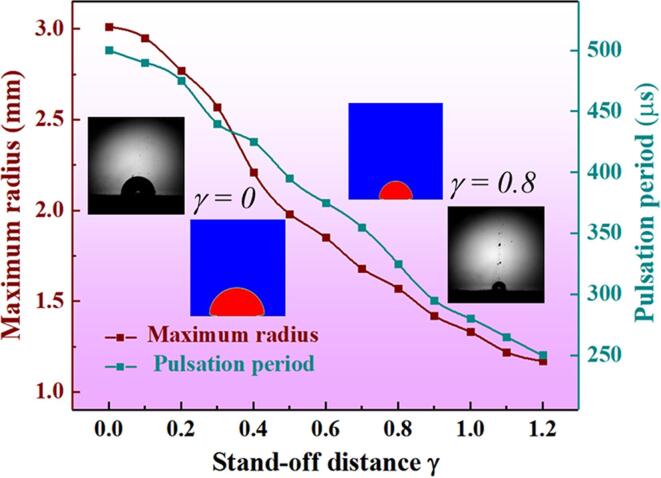

3.2. Bubble dynamic characteristics

The dynamic characteristics of the cavitation bubbles in the process of LCP were investigated, and the simulation results are shown in Fig. 8. In Fig. 8(a), the hemispherical bubble attaches to the solid boundary, and it expands rapidly at the stage of initial birth. Then the expansion velocity slows down until the bubble expands to the maximum radius. The contraction process of the bubble is not uniform. The bottom surface of the bubble contracts slowly while the bubble wall contracts faster, which can be explained by the pressure gradient between the liquid and the rigid wall. In the second pulsation, the radius and period of the bubble are much smaller than the first pulsation, and the shape is flatter. Fig. 8(b) shows the variation trend of bubble radius with a pulsation period at the first pulsation, and the maximum radius of bubbles are displayed in Fig. 8(c). Similar to the experiment, the bubble radius and pulsation period of the bubble decrease significantly with increasing thein the numerical simulation. The pulsation period of the bubble decreases from 500 to 325 as the decreases from 0 to 0.8, and the maximum radius decreases from 3.01 mm to 1.57 mm. When reaching the maximum radius, the bubble keeps unchanged about 50 and then begins to contract. Fig. 9 presents the variation trend of bubble maximum radius and pulsation period with . It can be found that the maximum radius and the pulsation period of the cavitation bubble have a good consistency, which decreases with increasing the of . From the increase of (0 to 1.2), the bubble maximum radius decreases by nearly a third and the pulsation period decreases by about half.

Fig. 8.

(a) Simulation of bubble pulsation sequence at various , (b) Change in the buble radius during the first pulsation period, (c) maximum radius of bubble at various .

Fig. 9.

Variation trend of bubble maximum radius and pulsation period with .

Fig. 10 presents the simulation of the pressure field distribution and the change in a pressure value in the bubble pulsation. The location of the monitoring point is 0.1 mm above the solid boundary. It is known to all that the expansion and contraction of cavitation bubble originates from the pressure difference inside and outside the cavitation. In the numerical simulation, the initial pressure inside the bubble is calculated, and then the pressure drops rapidly to zero as the bubble starts to expand. The pressure keeps zero in the first pulsation and rises again at the beginning of the second and third pulsation, but the pressure value decreases greatly. At , the pressure in the first pulsation is 910 Mpa while it decreases to 96 Mpa at the second pulsation, and the pressure only leaves with 13 Mpa in the third pulsation. It can be seen from the cloud diagram that the stratification of the pressure field is very obvious in the initial stage of the second expansion, which indicates that the pressure inside the bubble decreases gradually from the center to the surroundings. The simulation results of the temperature field distribution and the change in temperature value are displayed in Fig. 11. Similar to the pressure field, the temperature decreases fast at the initial expansion of the bubble and then tends to be stable gradually. From the end of the first bubble collapse to the beginning of the second expansion, the temperature rises sharply and then falls rapidly. In the third pulsation, the bubble keeps 300 K (temperature of liquid), and the extent of change in temperature at the third pulsation is too low. Moreover, it also should be noticed that the highest temperature of the bubble appears on the surrounding wall instead of the center.

Fig. 10.

Pressure field distribution and change in pressure value in the bubble pulsation.

Fig. 11.

Temperature field distribution and change in temperature value in the bubble pulsation.

3.3. Material strengthening

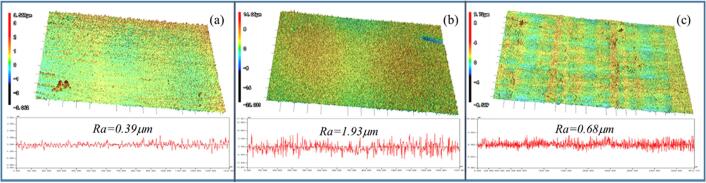

Plastic deformation is one of the important strengthening mechanisms of material treated by LSP and CP, which introduces residual stress on the surface layer and improves the yield strength of material [34], [35], [36]. The plastic deformation of Q235 steel after the treatment of LCP was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 12. It can be observed from Fig. 12(a) that the surface of the substrate is relatively flat and the roughness is only 0.39 . After the treatment of LCP without coverage (LCPwc) (see Fig. 12(b)), the plastic deformation generates on the specimen surface because of the impact of the shock wave and water-jet. Due to the laser ablation and cavitation erosion, the traces of impact are not obvious, and the roughness increases to 1.93 . In Fig. 12(c), the traces of LCP impact and plastic deformation are obvious, and the roughness is only 0.68 The presence of coverage layer causes the extent of plastic deformation after LCP treatment is relatively lower than that after LCPwc treatment, but it avoids the damage of specimen in the process of LCP and makes the surface integrity is better [37]. Grain refinement of the material surface layer caused by plastic deformation is another mechanism of material strengthening [38], [39]. Fig. 13 shows the cross-sectional morphology of Q235 steel grains after LCP and LCPwc treatment. It can be observed that the grains of Q235 specimen on the surface layer after treatment are significantly refined compared to the substrate. The extent of grain refinement on the specimen surface is the greatest, and the size of the grains gradually increases with the distance from the impact surface, so the grain refinement caused by plastic deformation presents a gradient distribution. The depth of the grain refinement layer under the two treatments is similar, with an average of about 20–30.

Fig. 12.

Surface morphology and roughness of Q235 steel, (a) substrate, (b) LCPwc treated, (c) LCP treated.

Fig. 13.

The optical morphology (a) LCP treated and (b) LCPwc treated and local magnified area (A), (B) and (C) of the grain structure of Q235 steel specimen section.

The residual stress and microhardness of Q235 steel introduced by LCP and LCPwc were investigated, as shown in Fig. 14. The corresponding maximum radius of the cavitation bubble is listed in Table. 4. LCP introduces the residual stress and improves the microhardness in the surface layer of Q235 steel. In the case of LCP treatment, the enhancement of residual stress and micro-hardness increases with the increase of . From to = 1.2, residual stress decreases from −126 Mpa to −36 Mpa, and the microhardness decreases from 134.9 HV to 115.8 HV. The increase ofmeans that the laser focus is far away from the specimen surface, which causes the shock wave and water-jet cannot impact the specimen surface completely, and the presence of coverage layer further weakens the impact. The weaker impact effect makes the surface plastic deformation of the specimen lower, so the increase in residual stress and micro-hardness are smaller when the is larger. Moreover, the laser has a multi-point breakdown of the liquid when is large, which loses the energy severely. It can be observed from the figure that the residual stress and microhardness after LCPwc treatment increase firstly and then decreases with increasing the, and the optimal value of is 0.4. At the range of to 0.4, although the impact intensity of shock wave and water-jet is relatively large, laser ablation and cavitation erosion will damage the specimen surface seriously, so the enhancement in residual stress and microhardness is not very large when is small. The impact intensity of shock wave and water-jet is weakened as increasing the , while the extent of laser ablation and cavitation erosion also decrease obviously, so the strengthening effect will increase at a certain range. The improvement of residual stress and microhardness treated by LCPwc is better than that treated by LCP when exceeds 0.4. This is due to the absence of coverage layer in the case of bigger makes the impact of the shock wave and water-jet impacting on the specimen surface fully, and the damage of specimen surface is weaker and can be ignored.

Fig. 14.

(a) Residual stress and (b) microhardness on the Q235 steel surface introduced by LCP and LCPwc.

Table 4.

Bubble maximum radius at variouscorresponding to the residual stress and microhardness.

| γ | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rmax | 3.13 | 3.03 | 2.76 | 2.67 | 2.26 | 2.03 | 1.83 | 1.72 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.51 | 1.46 | 1.39 |

To further study the impact effect of LCP, the impact of the laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet on Q235 steel were simulated, and the results are displayed in Fig. 15. The impact pressure of shock wave and water-jet setting in the simulation were obtained by the hydrophone and water hammer equation at = 0. LCP can be divided into three stages of impact, in which laser shock wave has the largest impact pressure. Fig. 15(a) and (b) present the equivalent plastic strain and stress field, respectively. Firstly, the laser shock wave impacts the Q235 surface, which causes plastic deformation and introduces residual stress. Then the bubble collapse shock impacts the surface again, and the extent of plastic deformation and the value of residual stress increases. The last impact originates from the water-jet. Although the impact pressure of the water-jet is smaller than that of the shock wave, the impact of the water-jet is a continuous and spreading process, so the surface of the material is further strengthened. It can be observed that the impact of laser shock wave plays the main role in the process of material strengthening by LCP. Based on the plastic deformation caused by laser shock wave, the continued impact of the bubble collapse shock wave and water-jet double the strength of the material.

Fig. 15.

Simulation of (a) equivalent plastic strain and (b) stress field of Q235 steel after the impact of laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave and water-jet.

3.4. Chemical effect

The generation of ·OH radical is a special phenomenon during the process of LCP. Shock waves and water-jets tear the water molecules, and thereby generates the free radicals (·OH and ·H), as seen in equation (4). Moreover, the high temperature and high-pressure environment caused by laser breakdown and bubble collapse can also cause the water molecules to crack. Hydroxyl radical is a kind of radical with a strong oxidizing ability (oxidation potential is 2.81 V), which has the characteristics of high activity and fast reaction rate [40], [41], [42]. It can react with various organic compounds and oxide them into carbon dioxide, water, and other harmless substances through electron transfer, electrophilic addition, dehydrogenation reaction, and other ways [43], [44].

| H2O ·OH + H | (4) |

The degradation of MB solution during the LCP was investigated, as shown in Fig. 16. In Fig. 16(a), it can be observed that the degradation rate gradually increases with the progress of LCP, and the final degradation rate for 60 min are 26.4%, 41.7%, and 34.5%. The degradation rate of MB in the infinite domain is lower than that in a rigid wall, and the degradation rate by LCPwc is the highest. Fig. 16(b) shows the degradation velocity of MB in the conditions of the infinite domain, LCP, and LCPwc. Similar to the degradation rate, the velocity of degradation increases significantly within 60 min, and the increasing extent is greater within 40–60 min. This is because the concentration of MB solution decreases as the LCP progresses, so the diffusion extent of ·OH radical begins to increase and the MB molecules are more easily oxidized. The degradation velocity of MB in LCPwc is 1.66810−3 mg/min, which is higher than that in the infinite domain (1.05610−3 mg/min) and LCP (1.38110−3 mg/min). The solution of MB after LCP was detected through liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS), as shown in Fig. 17. Fig. 17(a) shows LC/MS analysis of MB solution after LCP treatment for 30 min, and Fig. 17(b) displays the mass spectra of the major detected products. The MB is detected at m/z = 284, and other compounds occur at m/z = 270, 256, 242, and 228, respectively. It can be determined that the reaction of ·OH radical and MB is to cleave one or more methyl groups on the amine group [45].

Fig. 16.

(a) Degradation rate and (b) degradation velocity of MB solution.

Fig. 17.

(a) LC/MS analysis of MB solution after LC for 30 min, (b) mass spectra of the major detected products.

The experimental results can be attributed to the intensity difference of the shock wave and water-jet. The laser breakdown in infinite domain liquid usually presents the multi-point puncture, and the laser energy is dispersed and thereby generates the bubble string, so the intensity of laser shock wave is low. The detected value of laser shock wave in the infinite domain is only 287 Mpa (see Fig. 18), which is far lower than that in LCP. The pulsation period of the cavitation bubble decreases about two-thirds, and the bubble radius also decreases significantly. Due to the serious dissipation of laser energy and the generation of bubble string, the bubble energy is too low and the collapse shock wave only has 133 Mpa. Brujan [46] also reported the shock wave emission by an optical breakdown in the infinite domain. When the femtosecond pulse laser energy decreases from 74.1 nJ to 38 nJ, the shock wave pressure decreases from 49.2 kPa to 25.7 kPa. Moreover, the water-jet will not generate when the bubble collapses in the infinite domain. The generation of ·OH radical in the infinite domain only relies on the low-intensity laser shock wave and bubble collapse shock wave to tear the water molecule, so the water molecules in the infinite domain are not easy to be torn. The production of ·OH radical will decrease, which is insufficient to react with MB molecules. The higher degradation rate in LCPwc may be explained by the generation of Fenton reagents. In LCPwc, the focused laser beam impacts the surface of Q235 steel directly, so the Q235 surface is damaged by laser ablation and cavitation erosion, and thereby causing the Fe ions are dissolved in the solution. The generated ·OH radical can self-react into the H2O2 (see equation (5)), and the ferrous ions react with H2O2 to form ·OH radical (see equation (6)), which accelerates the degradation of MB. The Q235 surface is covered on aluminum foil in LCP, so it will not be damaged and cause the dissolution of Fe ions.

| ·OH + ·OH H2O2 | (5) |

| Fe2+ + H2O2 Fe3+ + ·OH + OH– | (6) |

Fig. 18.

Acoustic signal and bubble evolution in infinite domain.

4. Conclusion

The bubble dynamic evolution, material strengthening, and chemical effect induced by LCP were reported. LCP is a composite impact process of the laser shock wave, bubble collapse shock wave, and water-jet, and the laser shock wave plays the main role. The intensity of shock wave and water-jet decreases as the increase of, and the detected value are 989 Mpa, 763 Mpa, and 369 MPa at . From the increase of (0 to 1.2), the bubble maximum radius decreases by nearly a third (from 3.01 mm to 1.15 mm), and the pulsation period decreases by about half (from 500 to 255). The pressure and temperature of the cavitation bubble drop significantly during the second and third pulsations, and the maximum pressure and temperature when the bubble expands appear on the surrounding wall of the bubble. The impact of LCP causes plastic deformation on the Q235 steel surface and refines the grains on the surface layer within a depth of 20–30. The coverage layer decreases the extent of plastic deformation while it decreases the surface roughness significantly. The improvement of residual stress and micro-hardness induced by LCP is proportional to , and the optimal value for LCPwc is 0.4. The ·OH radical produces in the process of LCP, which degrades the MB solution. The reaction of ·OH radical and MB is to cleave one or more methyl groups on the amine group. The degradation rate in the infinite domain, LCPwc, and LCP are 26.4%, 41.7%, and 34.5%.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jiayang Gu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Chunhui Luo: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Zhubi Lu: Writing - review & editing. Pingchuan Ma: Writing - review & editing. Xinchao Xu: Writing - review & editing. Xudong Ren: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the projects supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51975261), Innovation Team of Six Talents Peaks in Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 2019TD-KTHY-005).

References

- 1.Brujan E.A., Ohl C.D., Lauterborm W., Philipp A. Dynamics of laser-induced cavitation bubbles in polymer solutions. Acust. Acta Acust. 1996;82:423–430. doi: 10.1006/jsvi.1996.0208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brujan E.A., Nahen K., Schmidt P. Dynamics of laser-induced cavitation bubbles near an elastic boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 2001;433:251–281. doi: 10.1017/S0022112000003347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv L., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Y. Experimental investigations of the particle motions induced by a laser-generated cavitation bubble. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;56:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Dai J., Shi G., Li L., Wang G., Yang H. Sonocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B catalyzed by β-Bi2O3 particles under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuziuti T., Yasui K., Sivakumar M., Iida Y., Miyoshi N. Correlation between acoustic cavitation noise and yield enhancement of sonochemical reaction by particle addition. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005;109(21):4869–4872. doi: 10.1021/jp0503516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chahine G.L., Kapahi A., Choi J.-K., Hsiao C.-T. Modeling of surface cleaning by cavitation bubble dynamics and collapse. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:528–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohl C.-D., Arora M., Dijkink R., Janve V., Lohse D. Surface cleaning from laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89(7):074102. doi: 10.1063/1.2337506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z., Gao S.J., Zhao Y. Disruption of tumor neovasculature by microbubble enhanced ultrasound: a potential new physical therapy of anti-angiogenesis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012;38:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi K., Kodama T., Takahira H. Shock wave–bubble interaction near soft and rigid boundaries during lithotripsy: numerical analysis by the improved ghost fluid method. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011;56(19):6421–6440. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/19/016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soyama H., Kikuchi T., Nishikawa M., Takakuwa O. Introduction of compressive residual stress into stainless steel by employing a cavitating jet in air. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011;205(10):3167–3174. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2010.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soyama H., Takeo F. Comparison between cavitation peening and shot peening for extending the fatigue life of a duralumin plate with a hole. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2016;227:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke M., Braeutigam P., Wu Z.-L., Ren Y., Ondruschka B. Enhancement of chloroform degradation by the combination of hydrodynamic and acoustic cavitation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18(4):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X.M., He J., Lu J., Ni X.W. Effect of surface tension on a liquid-jet produced by the collapse of a laser-induced bubble against a rigid boundary. Opt. Laser Technol. 2009;41(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2008.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren X.D., Wang J., Yuan S.Q., Adu-Gyamfi S., Tong Y.Q., Zuo C.Y., Zhang H.F. Mechanical effect of laser-induced cavitation bubble of 2A02 alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018;105:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.02.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu J., Luo C., Zhou W., Tong Z., Zhang H., Zhang P., Ren X. Degradation of Rhodamine B in aqueous solution by laser cavitation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;68:105181. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y., Qiu X.u., Zhang X., Tang N., Zhang Y. Collapsing dynamics of a laser-induced cavitation bubble near the edge of a rigid wall. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67:105157. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yella P., Venkateswarlu P., Buddu R.K., Vidyasagar D.V., Sankara Rao K.B., Kiran P.P., Rajulapati K.V. Laser shock peening studies on SS316LN plate with various sacrificial layers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;435:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.11.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganesh P., Sundar R., Kumar H., Kaul R., Ranganathan K., Hedaoo P., Raghavendra G., Anand Kumar S., Tiwari P., Nagpure D.C., Bindra K.S., Kukreja L.M., Oak S.M. Studies on fatigue life enhancement of pre-fatigued spring steel specimens using laser shock peening. Mater. Des. (1980-2015) 2014;54:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2013.08.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong Y.Q., Wang C., Yuan S.Q. Compound strengthening and dynamic characteristics of laser-induced double bubbles. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019;113:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H., Ren X., Tong Y., Asuako Larson E., Adu-Gyamfi S., Wang J., Li X. Surface integrity of 2A70 aluminum alloy processed by laser-induced peening and cavitation bubbles. Results Phys. 2019;12:1204–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.11.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasoh A., Watanabe K., Sano Y., Mukai N. Behavior of bubbles induced by the interaction of a laser pulse with a metal plate in water. Appl. Phys. A. 2005;80(7):1497–1500. doi: 10.1007/s00339-004-3196-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren X.D., He H., Tong Y.Q., Ren Y.P., Yuan S.Q., Liu R., Zuo C.Y., Wu K., Sui S., Wang D.S. Experimental investigation on dynamic characteristics and strengthening mechanism of laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;32:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brujan E.A., Vogel A. Stress wave emission and cavitation bubble dynamics by nanosecond optical breakdown in a tissue phantom. J. Fluid Mech. 2006;558:281–308. doi: 10.1017/S0022112008002322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brujan E.A., Ikeda T., Matsumoto Y. Jet formation and shock wave emission during collapse of ultrasound-induced cavitation bubbles and their role in the therapeutic applications of high-intensity focused ultrasound. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;50(20):4797–4809. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/20/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brujan E.A., Ikeda T., Matsumoto Y. On the pressure of cavitation bubbles. Exp. Therm Fluid Sci. 2008;32:1188–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2008.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao-wu Ni, Biao Zou, Jian-ping Chen, Bao-min Bian, Zhong-hua Shen, Jian Lu, Yi-ping Cui. On the generation of laser-induced plasma acoustic waves. Acta Phys. Sin. (Overseas Edn) 1998;7(2):143–147. doi: 10.1088/1004-423X/7/2/007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noack Joachim, Vogel Alfred. Single-shot spatially resolved characterization of laser-induced shock waves in water. Appl. Opt. 1998;37(19):4092. doi: 10.1364/AO.37.004092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Yuan Xiang, Wang Qian Xi, Keat T.S. Dynamic features of a laser-induced cavitation bubble near a solid boundary. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(4):1098–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X., Xu R.Q., Shen Z.H., Lu J., Ni X.W. Optical investigation of cavitation erosion by laser-induced bubble collapse. Opt. Laser Technol. 2004;36(3):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2003.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward B., Emmony D.C. Direct observation of the pressure developed in a liquid during cavitation bubble collapse. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1991;59:2228–2230. doi: 10.1063/1.106078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han Bing, Zhu Rihong, Guo Zhenyan, Liu Liu, Ni Xiao-Wu. Control of the liquid jet formation through the symmetric and asymmetric collapse of a single bubble generated between two parallel solid plates. Eur. J. Mech. B. Fluids. 2018;72:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechflu.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philipp A., Lauterborn W. Cavitation erosion by single laser-produced bubbles. J. Fluid Mech. 1998;361:75–116. doi: 10.1017/S0022112098008738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogel A., Lauterborn W., Timm R. Optical and acoustic investigations of the dynamics of laser-produced cavitation bubbles near a solid boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 2006;206 doi: 10.1017/S0022112089002314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klaseboer E., Fong S.W., Turangan C.K. Interaction of lithotripter shockwaves with single inertial cavitation bubbles. J. Fluid Mech. 2007;593:33–56. doi: 10.1017/S002211200700852X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi Koji, Osedo Hiroko, Suzuki Takaya, Fukuda Shinsaku. Fatigue strength improvement of an aluminum alloy with a crack-like surface defect using shot peening and cavitation peening. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2018;193:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karthik D., Yazar K.U., Bisht Anuj, Swaroop S., Srivastava Chandan, Suwas Satyam. Gradient plastic strain accommodation and nanotwinning in multi-pass laser shock peened 321 steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;487:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu Jiayang, Luo Chunhui, Zhang Penghua, Ma Pingchuan, Ren Xudong. Laser cavitation peening of gray cast iron: effect of coverage layer on the surface integrity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;521:146295. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu J.Z., Wu L.J., Sun G.F., Luo K.Y., Zhang Y.K., Cai J., Cui C.Y., Luo X.M. Microstructural response and grain refinement mechanism of commercially pure titanium subjected to multiple laser shock peening impacts. Acta Mater. 2017;127:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2017.01.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu J.Z., Luo K.Y., Zhang Y.K., Sun G.F., Gu Y.Y., Zhou J.Z., Ren X.D., Zhang X.C., Zhang L.F., Chen K.M., Cui C.Y., Jiang Y.F., Feng A.X., Zhang L. Grain refinement mechanism of multiple laser shock processing impacts on ANSI 304 stainless steel. Acta Mater. 2010;58(16):5354–5362. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2010.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajoriya Sunil, Bargole Swapnil, Saharan Virendra Kumar. Degradation of a cationic dye (Rhodamine 6G) using hydrodynamic cavitation coupled with other oxidative agents: reaction mechanism and pathway. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Xing, Yao Jilun, Zhao Zhiwei, Liu Jie. Degradation of haloacetonitriles with UV/peroxymonosulfate process: Degradation pathway and the role of hydroxyl radicals. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;364:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matilainen Anu, Sillanpää Mika. Removal of natural organic matter from drinking water by advanced oxidation processes. Chemosphere. 2010;80(4):351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai Meiqiang, Su Jie, Zhu Yizu, Wei Xiaoqing, Jin Micong, Zhang Haojie, Dong Chunying, Wei Zongsu. Decolorization of azo dyes Orange G using hydrodynamic cavitation coupled with heterogeneous Fenton process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;28:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ou Yining, Wu Jiewei, Meyer James R., Foston Marcus, Fortner John D., Li Wenlu. Photoenhanced oxidation of nC60 in water: Exploring H2O2 and hydroxyl radical based reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;360:665–672. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.12.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rauf Muhammad A., Meetani Mohammed A., Khaleel A., Ahmed Amal. Photocatalytic degradation of Methylene Blue using a mixed catalyst and product analysis by LC/MS. Chem. Eng. J. 2010;157(2-3):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brujan E.A. Shock wave emission and cavitation bubble dynamics by femtosecond optical breakdown in polymer solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;58 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]