Abstract

Introduction

Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) is a common cause of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) globally and is one of the most fatal infectious diseases for infants in developing countries. Of those infected, 25%–40% aged ≤1 year develop severe lower RTIs leading to pneumonia and bronchiolitis, with ~10% requiring hospitalisation. Evidence also suggests that HRSV infection early in life is a major cause of adult asthma. There is no HRSV vaccine, and the only clinically approved treatment is immunoprophylaxis that is expensive and only moderately effective. New anti-HRSV therapeutic strategies are therefore urgently required.

Methods

It is now established that viruses require cellular ion channel functionality to infect cells. Here, we infected human lung epithelial cell lines and ex vivo human lung slices with HRSV in the presence of a defined panel of chloride (Cl−) channel modulators to investigate their role during the HRSV life-cycle.

Results

We demonstrate the requirement for TMEM16A, a calcium-activated Cl− channel, for HRSV infection. Time-of-addition assays revealed that the TMEM16A blockers inhibit HRSV at a postentry stage of the virus life-cycle, showing activity as a postexposure prophylaxis. Another important negative-sense RNA respiratory pathogen influenza virus was also inhibited by the TMEM16A-specific inhibitor T16Ainh-A01.

Discussion

These findings reveal TMEM16A as an exciting target for future host-directed antiviral therapeutics.

Keywords: airway epithelium, infection control, paediatric lung disaese, respiratory infection, viral infection

Key messages.

What is the key question?

If we can identify a new druggable cellular target to inhibit human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV).

What is the bottom line?

The current COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the ever-present need for front-line antiviral therapeutics, and no effective vaccines or drugs for HRSV are currently available.

Why read on?

We reveal the ability to inhibit HRSV with Cl− channel modulators, highlighting their promise as anti-HRSV therapeutics with the potential for drug repurposing.

Introduction

Human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) is one of the most significant causes of respiratory tract infections worldwide. The greatest risk factor for HRSV-related disease is age, with 95% of children becoming infected before the age of 2 years and an increased susceptibility in those aged over 65 years.1 2 The developing morphology of infant airways increases the severity of symptoms, as their narrower bronchioles are more susceptible to HRSV-induced inflammation.3 As a result, 25%–40% of infants with lower respiratory tract infections develop bronchiolitis or pneumonia and ~10% require hospitalisation, where they receive supplemental oxygen or intubation to improve ventilation. HRSV causes ~1 99 000 deaths per year, 99% of which occur in developing countries.2 The virus also imposes a heavy financial burden on healthcare systems and is an under-recognised cause of morbidity in the elderly.1 Diagnostic testing is not recommended in routine cases and treatment is supportive.4 Certain high-risk groups of children that test positive may receive ribavirin, the efficacy of which is questionable.4 5 Immunoprophylaxis with palivizumab is also available, but its effectiveness is moderate, and its expense limits its administration.4 No antiviral drugs to treat HRSV infection are currently available in the clinic.

HRSV is an orthopneumovirus within the family Pneumoviridae, a large and diverse grouping of non-segmented negative-sense single-stranded RNA (-ssRNA) viruses.6 HRSV particles are pleomorphic, adopting spherical, filamentous and asymmetric forms that vary from 100 to 1000 nm in size.7 The HRSV genome encodes 10 genes (3′-NS1-NS2-N-P-M-SH-G-F-M2-L-5′) that are tightly encapsidated by the nucleoprotein (N) to form a helical nucleocapsid.8 Mature virions possess a host-derived lipid envelope containing three structural proteins: the glycoprotein (G), fusion protein (F) and a small hydrophobic protein (SH), which form individual protruding spikes. The matrix protein (M) lies on the internal interface of the envelope and acts as a bridge connecting the structural transmembrane proteins to N bound to the RNA genome.7 The binding of RNA with multiple copies of N forms the characteristic ribonucleocapsids, which in turn interact with the phosphoprotein (P) and the large polymerase (L) to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, the fundamental machinery required for HRSV transcription and replication.8

One strategy to prevent HRSV infection is to target key virus–host interactions that are essential for virus multiplication. Ion channels are emerging as key factors required during virus replicative cycles, examples including the roles for potassium (K+) channels in Bunyamwera virus (BUNV) infection9 10; two-pore calcium (Ca2+) channels in Ebola virus (EBOV) infection11 and chloride (Cl−) channels in chikungunya virus (CHIKV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), BK polyomavirus and Merkel cell polyomavirus infection.12–15 Cl− channels are diverse families of proteins that regulate cell excitability and fluid and osmolyte secretion in lung epithelial cells. Over 40 genes are linked to Cl− conductances which can be categorised into voltage-gated Cl− channels (ClC), ligand-gated Cl- channels, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), volume-regulated anion channels and Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) families.16

Herein, we reveal that a new host factor TMEM16A/ANO1, a calcium-activated Cl− channel, is required during HRSV infection. We propose that targeting TMEM16A Cl− conductances may represent a new and pharmacologically safe therapeutic strategy for this important human pathogen.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and virus strains

A549 (adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells), HEp-2 (human epithelial cells) and SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma cells) were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, 100 U/mL and 100 µg/mL, respectively). Wild type HRSV-A2 was obtained from the National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses (NCPV) of Public Health England (PHE). HRSV-GFP was purchased from ViraTree (HRSV-GFP). GFP-PA-labelled influenza A virus (IAV-GFP) was rescued as previously described.17

Plaque assays

HEp-2 monolayers were infected with serially diluted virus and overlayed with 1.6% methylcellulose (Sigma, 1500 cP): DMEM (10% FBS, 1% P/S) prior to incubation at 37°C for 5 days. Cells were washed, fixed in 80% methanol and blocked in 5% milk in phosphate-buffered saline, 0.1% tween 20 detergent (PBS-T). Plaques were detected using goat α-HRSV (Abcam ab20745, 1:200) and HRP-conjugated rabbit α-goat (Sigma A8919, 1:5000) and imaged following incubation with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (4-CN, Pierce, 1:10) and 30% H2O2 (Sigma).

Cl− channel inhibitor assays

A549 or SH-SY5Y cells (1×104 cells/well) in 96 wells were pretreated with the indicated Cl− channel blockers and infected with HRSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1) in the presence of each inhibitor for 24 hours. HRSV-GFP fluorescence was visualised using an IncuCyte ZOOM imager (IncuCyte, Essen Bioscience). Fluorescence was quantified using accompanying analysis software. The Cl− channel modulators used in the study were as follows: broad-spectrum Cl− channel inhibitors 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB—Sigma-Aldrich, N4779), 4,4ʹ-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2ʹ-disulfonic acid (DIDS—Sigma-Aldrich, D3514) and R(+)-[(6,7-Dichloro-2-cyclopentyl-2,3-dihydro-2-methyl-1-oxo-1H-inden-5-yl)-oxyacetic acid (R+IAA-94—Sigma-Aldrich, I117); CFTR inhibitors: CFTRinh-172 (Sigma-Aldrich, C2992), chromanol 293B (Sigma-Aldrich, C2615) and glibenclamide (Tocris Biosciences, 0911); CaCC inhibitors: CaCCinh-A01 (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0916), niflumic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, N0630), talniflumate (Sigma-Aldrich, SML1710) and tannic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, 403040); TMEM16A inhibitors: T16Ainh-A01 (Merck Chemicals, 613551) and MONNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0902). Ribavirin (Sigma-Aldrich, R9644) was included as a known HRSV inhibitor.

Cell viability assays

For viability assessments, drug-treated cells were incubated with CellTiter96 AQueous One Solution (Promega) at 37°C for 1 hour. Absorbances were measured at 492 nm on a microplate reader.

Time of addition assays

A549 cells (1×104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were treated with inhibitors prepared at 2× working concentrations in DMEM (2% FBS, 1% P/S) and an equal volume of HRSV-GFP supernatant (MOI 0.1, T=0). For postinfection treatments, drugs were added at 3, 6 or 9 hours postinfection (hpi). HRSV-GFP expression was assessed via IncuCyte analysis at 24 hpi (eg, when added at 9 hpi, the inhibitor contacted the cells for 15 hours prior to the analysis of GFP expression).

Virion treatments

Channel inhibitors were prepared to 2× working concentrations in DMEM (2% FBS, 1% P/S) and directly added to an equal volume of HRSV MOI 0.2 for 45 min at room temperature. The virus/inhibitor mix was then diluted into media (3 mL per well) and added to A549 cells for 24 hours (MOI 0.2; final inhibitor concentration on cells ≥400-fold dilution from active concentration). HRSV gene expression was assessed via western blotting.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested in lysis buffer (25 mM glycerol phosphate, 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM Na4O7P2—pH 7.4) supplemented with halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Lysates were resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred to methanol-activated polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) using a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 10% (w/v) milk in TBS-T and probed with the appropriate primary antibodies (goat α-HRSV (Abcam ab20745, 1:1000); mouse α-GAPDH (Santa Cruz sc47724, 1:1000)) in 5% milk. Membranes were labelled with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma: goat α-mouse (Sigma A4416, 1:5000); rabbit α-goat (Sigma A8919, 1:5000)) in 5% milk and target proteins were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Advansta) and developed on CL-Xposure film using an Xograph processor. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ.

IncuCyte analysis

An IncuCyte ZOOM instrument (IncuCyte) and accompanying software (2018A) were used to analyse HRSV-GFP fluorescence. Plates were scanned using the 10× objective in both the phase and green channels. The processing definition was set on an individual basis using top-hat background subtraction, threshold (GCU), radius (µM), edge sensitivity and area filter (µm2). The total green object count (1/well) or the average integrated intensity (GCU × µm2) were recorded.

Preparation of precision-cut lung slices

Primary human lung tissue was provided by KRH Klinikum Siloah-Oststadt-Heidehaus (Hanover, Germany) from patients with cancer who underwent lung resection. Samples were provided from ≥3 donors. Human precision-cut lung slices (PCLS) were generated from disease-free tissue as previously described.18 Briefly, lobes were filled with 2% agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) via the bronchi. Solidified tissue was punched into cores of 8 mm diameter and cut into slices of 300–350 µm on a microtome (Krumdieck Tissue Slicer, Alabama Research and Development, Munford, Alabama, USA). PCLS containing airways were microscopically checked for ciliary movement and cultured in 24-well plates in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1 % P/S (10 000 U/mL, Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight.

Ex vivo infection experiments using human PCLS

PCLS were drug-treated for 40 min in DMEM/F12 (1% P/S) and subsequently infected with HRSV (106 pfu/mL) or UV-inactivated virus. Supernatants were collected after 24 hours, and tissues were lysed in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (Lonza). Supernatants and lysates were supplemented with 0.02% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (P1860, Sigma-Aldrich). For viability assessments, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was assayed in the supernatants using Cytotoxicity Detection Kits (Roche). Interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10) secretion was measured using the Human CXCL10/IP-10 ELISA DuoSet (R&D Systems). Total protein content was measured via BCA assay (Thermo Scientific). Virus protein production was assessed by western blotting.

For immunofluorescent analysis, human airway containing PCLS were inoculated with 106 pfu/mL HRSV for 2 hours and subsequently cultivated for 72 hours. After fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde, tissues were permeabilised with 0.3% Triton X-100 and blocked in 4% donkey serum prior to probing for HRSV (Goat IgG polyclonal to respiratory syncytial virus, Abcam, ab20745; 1:200) and for ARL13B (Cilia; Rabbit IgG polyclonal to ARL13B, Proteintech Group, 17 711-1-AP; 1:300) and staining with the appropriate secondary antibodies (Cy5 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L); Jackson ImmunoResearch, 705-176-147; 1:1000; Cy2 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L); Jackson ImmunoResearch, 711-225-152; 1:1000). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Immunofluorescence imaging was performed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, LSM 800).

Statistical analysis

Total green object count (1/well), average integrated intensity (GCU × µm2), western blot densitometry and cell viability data were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) Bonferroni multiple comparison test (Cl− channel inhibitor-treated cells vs solvent-treated controls). Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel (V.2013). Assays were verified using the known HRSV inhibitor ribavirin. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant (*) and are shown in supplemental file 3). For PCLS data, statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparison test or an unpaired Mann-Whitney one-tailed test using GraphPad Prism (V.8.3.1). P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

HRSV infection assays

For drug assays, we used a commercially available recombinant HRSV A2 variant (HRSV-GFP) that expresses eGFP from an independent transcriptional unit located in the promoter-proximal position. In A549 cells infected with HRSV-GFP, GFP was quantifiable ≥9 hpi (figure 1A) as assessed via live-cell IncuCyte analysis, consistent with the time course of WT-HRSV A2 gene expression previously reported in this cell line.19 HRSV-GFP-infected cells showed HRSV antigen positivity when stained with α-HRSV antibodies (figure 1B). Titres of the HRSV-GFP virus were comparable with those of the parental WT-HRSV A2 strain and produced an identical plaque morphology (figure 1C). HRSV-GFP infection was also inhibited by ribavirin, a known HRSV inhibitor (figure 1D), evidenced by the significant loss of HRSV-GFP fluorescence versus no-drug cells. These data confirmed the suitability of the HRSV-GFP system as a rapid and quantifiable method to identify inhibitory compounds against HRSV.

Figure 1.

Establishment of HRSV-GFP assays. (A) Time course of GFP expression in A549 cells infected with HRSV-GFP at MOI 0.1 (dashed line) and MOI 1 (solid line). (B) IncuCyte images of A549 cells infected with HRSV-GFP and co-stained with α-HRSV (red). (C) Comparison of WT-HRSV (left) and HRSV-GFP (right) plaques at a dilution factor of 10−4. (D(i)) Analysis of HRSV-GFP expression in A549 cells pretreated with increasing concentrations of ribavirin. Values are normalised to (H2O) control cells (GFP count per well—black bars). Relative cell viability (grey bars) determined via MTS assay. Experiments were performed in duplicate in 96-well plates and represent the average of four independent repeats (n=4)±SE. Independent replicates refer to repeat experiments performed on separate days using new batches of cells, drug and virus stocks to confirm reproducibility. Statistical significance p<0.05 is represented by an asterisk (*). (D(ii)) Representative IncuCyte ZOOM images of A549 cells treated with increasing concentrations of ribavirin (left to right) and infected with HRSV-GFP. Scale bar: 300 µm. HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; WT, wild type.

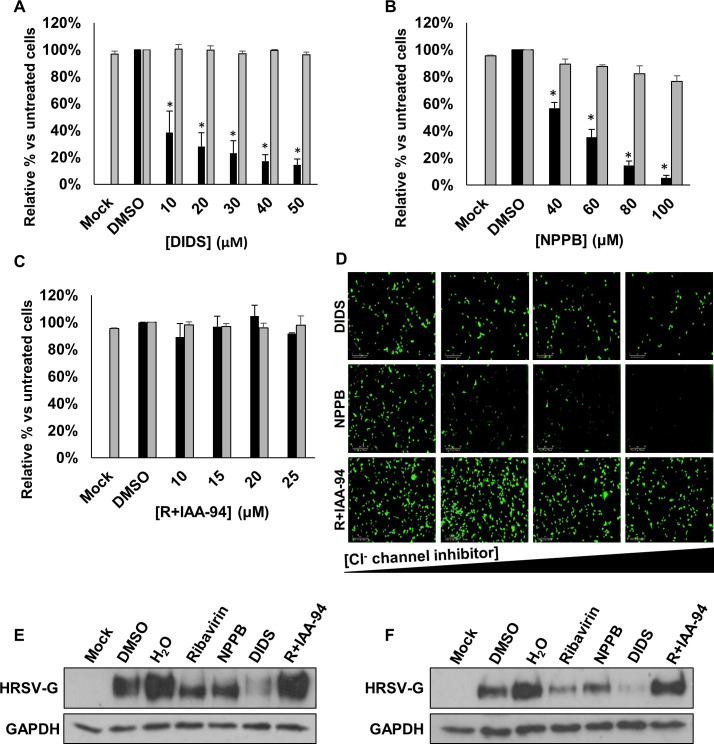

Blocking Cl− channels inhibits HRSV

Cl− channels are key regulators of transepithelial Cl− transport and fluid secretion in lung cells.16 To investigate their role during HRSV infection, we first assessed the effects of well-characterised broad-spectrum Cl− channel blockers including DIDS, NPPB and R+IAA-94 for their effects on HRSV (figure 2A–C, black bars, figure 2D). The addition of DIDS (10–50 µM) decreased HRSV-GFP expression in a concentration-dependent manner versus no-drug controls (62%–86% inhibition, figure 2A). A similar effect was observed following treatment with NPPB (40–100 µM, 43%–95% inhibition, figure 2B). In contrast, R+IAA-94 (5–25 µM), a more specific blocker of CLIC channels, had no effect on HRSV-GFP expression (figure 2C). At all concentrations assessed, the compounds were non-toxic as confirmed by MTS assays (figure 2A–C, grey bars). For confirmation of these data, WT-HRSV gene expression was assessed through western blotting of cell lysates for HRSV-G, a loss of which was observed in cells treated with ribavirin, DIDS and NPPB, while R+IAA-94 had no effect (figure 2E). These data were further confirmed in SH-SY5Y cells, a human neuronal cell-line permissive to HRSV20 (figure 2F). Taken together, these data suggest that HRSV infection is dependent on the function of a DIDS/NPPB-sensitive, R+IAA-94-insensitive Cl− channel to efficiently infect cells.

Figure 2.

Broad-spectrum Cl− channel inhibitors DIDS and NPPB decrease HRSV-GFP infection. (A–C) HRSV-GFP expression in A549 cells pretreated with broad-spectrum Cl− channel inhibitors DIDS (10–50 µM), NPPB (40–100 µM) and R+IAA-94 (10–25 µM), shown as a percentage of DMSO control cells (GFP count per well—black bars). Cell viability in each condition was determined via MTS assay (grey bars). Experiments were performed in duplicate in 96-well plates and represent the average of four independent repeats (n=4)±SE. p<0.05 is represented by an asterisk (*). (D) Representative Incucyte images of A549 cells treated with increasing concentrations of DIDS, NPPB and R+IAA-94 (left to right) and infected with HRSV-GFP. Images taken using IncuCyte ZOOM software. Scale bar: 300 µm. (E–F) Western blot analysis of wild type HRSV glycoprotein (G) expression as a marker of infection in A549 (left) or SH-SY5Y cells (right). Cells pretreated with NPPB (60 µM); DIDS (40 µM); R+IAA-94, (40 µM) or the known HRSV inhibitor ribavirin (60 µM) alongside solvent-treated controls (DMSO and H2O). GAPDH was probed as a loading control. DIDS, 4,4ʹ-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2ʹ-disulfonic acid; NPPB, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid.

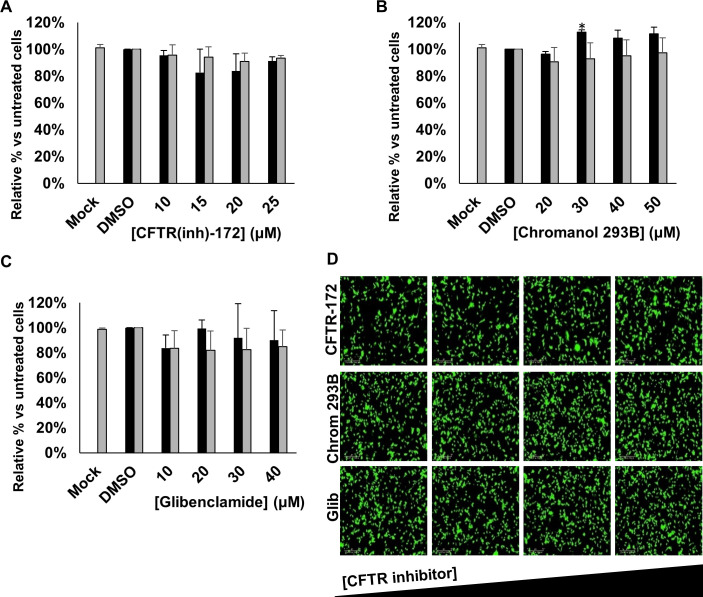

Inhibiting CFTR does not influence HRSV infection

The primary target for HRSV infection is the respiratory tract, in which the functions of CFTR are well-characterised.21 We therefore investigated the effects of specific CFTR inhibitors on HRSV infection using CFTR(inh)-172, chromanol 293B and glibenclamide. Treatment with each of the CFTR inhibitors had no effect on HRSV-GFP expression compared with no-drug controls (figure 3A–D). Given that these drugs failed to recapitulate the effects of either DIDS or NPPB, we reasoned that HRSV does not require CFTR activity during its infectious life-cycle.

Figure 3.

Inhibiting CFTR does not influence HRSV infection. (A–C) Number of HRSV-GFP expressing A549 cells treated with increasing concentrations of CFTR channel inhibitors CFTR(inh)-172 (10–25 µM), chromanol 293B (20–50 µM) or glibenclamide (10–40 µM), compared with DMSO-treated control cells (GFP count per well—black bars). Cell viability during each condition was determined via MTS assay (grey bars). Values are normalised to solvent control. Each experiment was performed in duplicate in 96-well plates and represents the average of four independent repeats (n=4)±SE. Statistical significance (p<0.05) is represented by an asterisk (*). (D) Representative IncuCyte images of HRSV-GFP-infected A549 cells treated with increasing concentrations of the CFTR channel inhibitors (left to right). Scale bar: 300 µm. CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus.

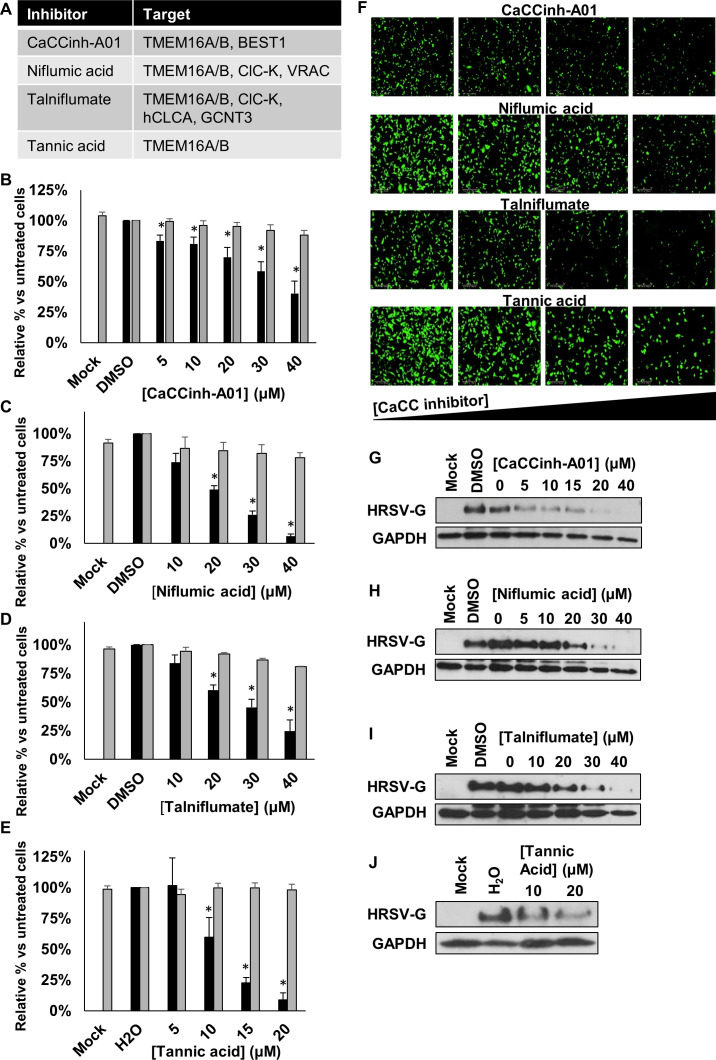

Blocking CaCCs inhibits HRSV infection

Several specific CaCC inhibitors are available, including CaCCinh-A01, niflumic acid, talniflumate and tannic acid22–24 (figure 4A). When A549 cells were infected in the presence of each of these compounds, a significant, concentration-dependent reduction in HRSV-GFP infection was observed at non-cytotoxic concentrations (figure 4B–F). A similar concentration-dependent loss of HRSV-G expression was observed in cells infected with WT-HRSV in the presence of each modulator, as assessed by western blotting (figure 4G–J). These data implicated a requirement for CaCC activity during HRSV infection.

Figure 4.

CaCC blockers inhibit HRSV infection. (A) Targets of the broad-spectrum CaCC inhibitors CaCCinh-A01, niflumic acid, talniflumate and tannic acid assessed in the study. (B–E) HRSV-GFP expression in A549 cells pretreated with CaCCinh-A01 (5–40 µM), niflumic acid (10–40 µM), talniflumate (10–40 µM) and tannic acid (5–20 µM) (GFP count per well—black bars) compared with solvent (DMSO or H2O) treated cells. Cell viability was determined by MTS assays (grey bars). Treatments were performed in duplicate and represent the average of four independent repeats (n=4), ±SE. Values were normalised to solvent-treated controls. Statistical significance is represented by asterisk (*) where p<0.05. (F) Representative Incucyte images showing the decrease in HRSV-GFP expression in cells pretreated with increasing concentrations of CaCC inhibitors (left to right). (G–J) Western blot analysis showing wild type HRSV-G expression as a marker of HRSV infection in treated cells. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. CaCC, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus.

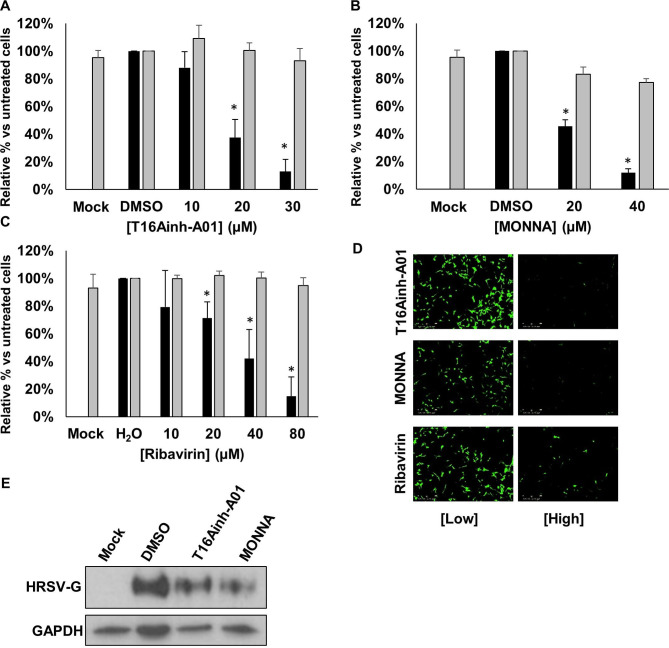

TMEM16A is the CaCC required during HRSV infection

Within the two CaCC subfamilies (anoctamins and bestrophins), TMEM16A (anoctamin 1) is expressed in lung epithelial cells.23 We used recently identified selective antagonists of TMEM16A; T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA,24 25 to assess their requirement during HRSV infection. Of note, we selected a pharmacological approach to target the Cl− functionality of TMEM16A, since gene-silencing approaches ablate the scaffolding and scramblase functions of this channel, leading to detrimental effects on cell growth.26 Cells were infected with HRSV-GFP in the presence of T16Ainh-A01 or MONNA (5–30 µM) and HRSV gene expression was assessed at 24 hpi. Figure 5A–C shows a significant reduction in HRSV-GFP expression in the presence of T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA that was confirmed by western blot analysis of WT-HRSV-treated cells (figure 5D). No cytotoxicity was observed at the inhibitory concentrations of each compound (figure 5A, B, grey bars). Importantly, we confirmed that the effects of T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA were cell mediated as the direct treatment of HRSV virions with T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA in the absence of cell treatment had no effect on HRSV infection (figure 5E). The inhibition of HRSV by these compounds was also independent of the MOI (figure 5F). We further confirmed that the requirement for TMEM16A was conserved during HRSV infection of SH-SY5Y cells, in which T16Ainh-A01 (10–30 µM) and MONNA (20–40 µM) inhibited HRSV-GFP in a concentration-dependent manner (figure 6A, B, D). At the highest, non-toxic concentrations assessed, HRSV-GFP expression was reduced by 87% and 88%, respectively. Ribavirin treatment led to a similar reduction in HRSV-GFP gene expression in this cell line (figure 6C, D). These data were confirmed by western blot analysis in which WT-HRSV-G expression was reduced following drug treatments (figure 6E) confirming the requirement for TMEM16A during HRSV infection.

Figure 5.

Modulation of TMEM16A decreases HRSV-GFP infection. (A–B) HRSV-GFP infection in A549 cells pretreated with TMEM16A-specific inhibitors T16Ainh-A01 (5–30 µM) and MONNA (5–30 µM) compared with solvent (DMSO) treated control cells (GFP count per well—black bars). Cell viability was determined via MTS assay (grey bars). Experiments were performed in duplicate and represent the average of four independent repeats (n=4) ±SE. Statistical significance is represented by an asterisk (*) where p<0.05. Values are normalised to solvent-treated controls. (C) Representative IncuCyte images in A549 cells pretreated with increasing concentrations of TMEM16A-specific inhibitors (left to right) and infected with HRSV-GFP for 24 hours. Scale bar: 300 µm. (D) Western blot analysis of HRSV-G expression in A549 cells treated with T16Ainh-A01 (20 µM); MONNA (20 µM) at 24 hpi. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. (E(i)). Representative western blot analysis of infection when HRSV virions were treated directly with CaCC inhibitors (CaCCinh-A01, 40 µM; T16Ainh-A01, 30 µM; MONNA, 20 µM) or known HRSV inhibitor ribavirin, 40 µM, prior to infection of A549 cells. Treated viruses were diluted in media ≥400-fold to ensure no effects of the drugs on cells. HRSV infection was assessed by western blot analysis. (E(ii)). Densitometry of HRSV-G expression normalised to GAPDH loading controls. Data are the average of three independent repeats (n=3) and are shown as a percentage of solvent-treated controls (DMSO or H2O)±SE. (F) A549 cells were pretreated with the indicated CaCC inhibitors and infected with wild type HRSV at MOI 0.1 (black), 0.5 (dark grey) and 1 (light grey). Data represent densitometric quantification of western blots from an average of three independent repeats±SE. CaCC, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 6.

TMEM16A blockers inhibit HRSV in neuronal cells. (A–C) Analysis of HRSV-GFP infection in SH-SY5Y (neuronal) cells pretreated with TMEM16A-specific inhibitors T16Ainh-A01 (10–30 µM) and MONNA (20–40 µM) and ribavirin (10–80 µM). Values are normalised to solvent-treated controls (DMSO or H2O) alongside cell viability assessments via MTS assays (grey bars). Data are the average of three independent repeats (n=3) ±SE. Statistical significance (p<0.05) are represented by an asterisk (*). (D) Representative IncuCyte images of HRSV-GFP expressing SH-SY5Y cells following CaCC channel modulation. Scale bars: 300 µm. (E) Western blot analysis of wild type HRSV-G expression in SH-SY5Y cells following treatment with T16Ainh-A01 (20 µM), MONNA (20 µM) or solvent (DMSO) control. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. CaCC, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus.

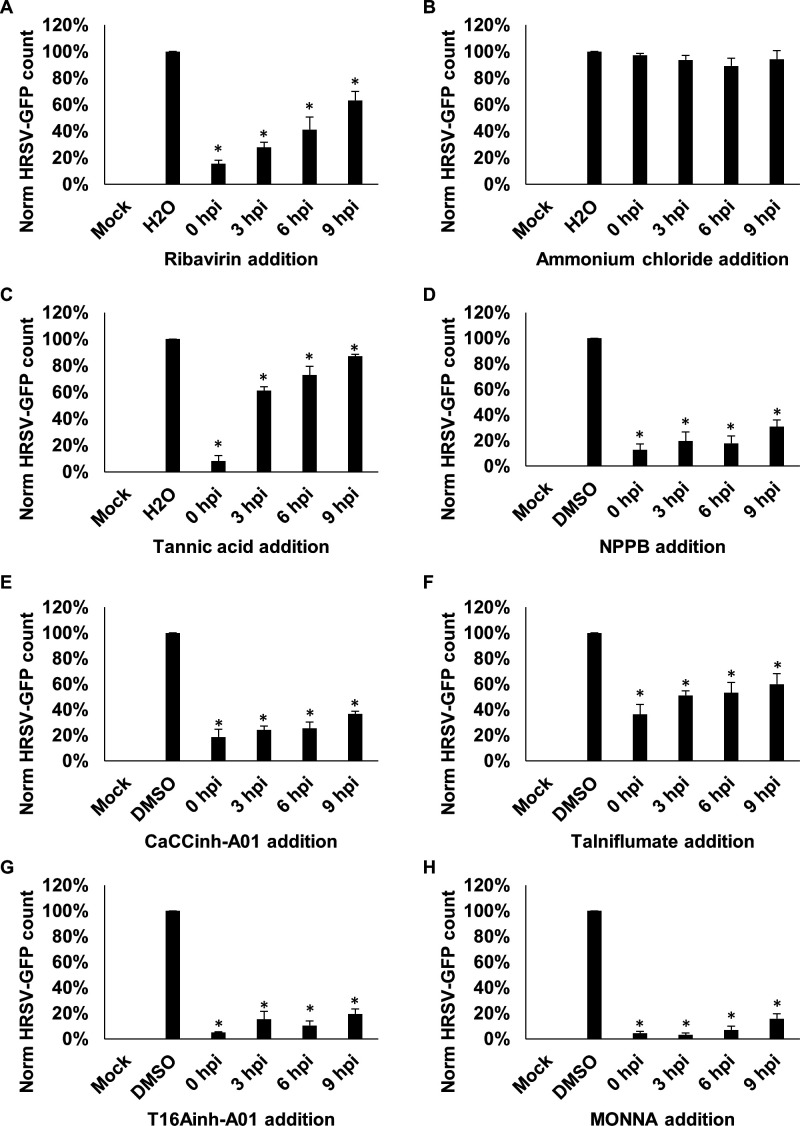

TMEM16A is required during a postentry stage of HRSV infection

We next determined the HRSV life-cycle stage requiring TMEM16A functionality. HRSV-GFP gene expression can be detected at 9 hpi (figure 1A), suggesting at this timepoint that the virus had penetrated cells and already established viral replication complexes.19 27 The ability of a compound to inhibit HRSV when added 9 hpi would therefore be suggestive of activity at a postentry stage. In the experiments that followed, cells were infected with HRSV-GFP, each channel modulator was added at defined timepoints postinfection, and HRSV-GFP expression was analysed at 24 hpi. As expected, the addition of ribavirin at 0–6 hpi inhibited HRSV-GFP expression, consistent with its ability to inhibit RNA chain elongation and viral mRNA capping after cell entry (figure 7A). Consistent with previous studies,28 the inhibition of endosomal acidification through the treatment of cells with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) failed to impact HRSV-GFP (figure 7B). Treatment with tannic acid showed a large reduction when added prior to HRSV-GFP infection (0 hpi) but showed reduced antiviral efficacy when added ≥3 hpi (figure 7C). This effect was consistent with the ability of this compound to prevent virus–receptor interactions as reported for HCV,29 HIV30 and norovirus,31 in addition to its effects on TMEM16A. Importantly, NPPB, CaCCinh-A01 and talniflumate (figure 7D–F), and the TMEM16A-specific inhibitors T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA (figure 7G, H) maintained their ability to inhibit HRSV when added up to 9 hpi. These data highlight TMEM16A modulators as inhibitors of the postentry stages of HRSV infection, thus showing promise as a postentry prophylaxis.

Figure 7.

CaCC inhibitors influence HRSV at a postentry stage of infection. (A–H) Time of addition assays in which A549 cells were infected with HRSV-GFP and treated with inhibitors at 0, 3, 6 or 9 hours postinfection (hpi). HRSV-GFP expression was assessed at 24 hpi. Ribavirin (40 µM) was included as positive control. NH4Cl (10 µM) was added to assess the effects of endosomal pH on virus infection. Inhibitor concentrations were as follows: NPPB (80 µM), CaCC inhibitors (tannic acid, 15 µM; CaCCinh-A01, 40 µM; talniflumate, 30 µM) and TMEM16A-specific inhibitors (T16ainh-A01, 30 µM; MONNA, 40 µM). Number of HRSV-GFP-expressing cells (GFP count per well) was normalised to solvent-treated cells (n=3)±SE. Statistical significance (p<0.05) are represented by an asterisk (*). CaCC, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; NPPB, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid.

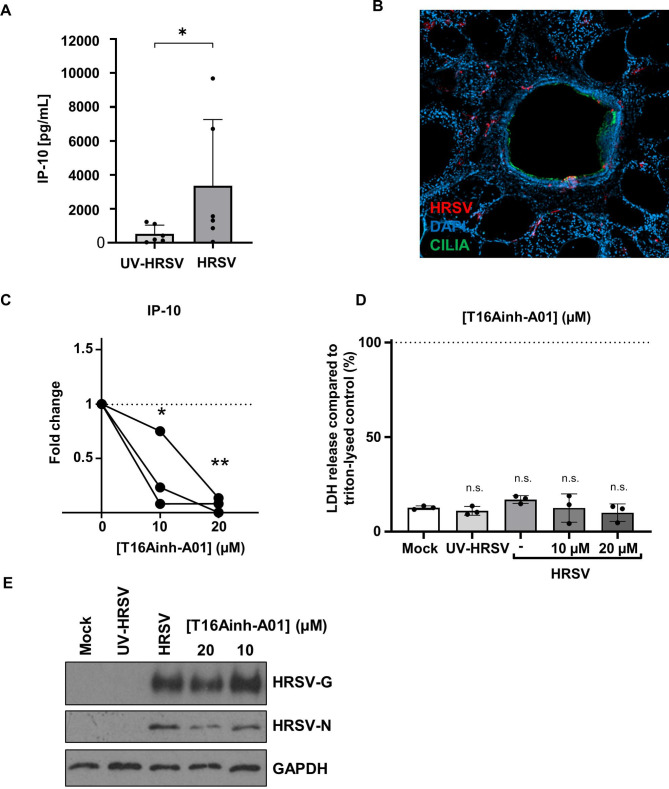

TMEM16A inhibits HRSV-induced IP-10 secretion in primary human lung tissue

TMEM16A is highly expressed in goblet cells, but it is also expressed to lower levels in the ciliated epithelium, where its silencing with short-interfering RNAs is known to block CaCC activity.32 This confirms that TMEM16A in ciliated epithelial cells (the major site of HRSV infection in the lungs) is the key mediator of Ca2+-dependent Cl− transport. We therefore investigated the effects of TMEM16A modulation on HRSV infection in human PCLS as more physiological models of virus infection. The PCLS system has been shown to support influenza A and rhinovirus (RV) infection in previous studies.33–35

In lung slices, actively replicating HRSV induces IP-10, whereas ultraviolet (UV)-inactivated virus is unable to increase IP-10 levels.33 We therefore investigated IP-10 as a surrogate marker for successful HRSV infection. Consistent with previous findings, we observed a significant increase in IP-10 secretion in PCLS infected with HRSV compared with UV-inactivated controls (figure 8A). Images of a PCLS airways infected with HRSV also showed specific HRSV staining and infection which co-localised with ciliated cells (figure 8B). These data validated the use of PCLS to further investigate the antiviral effects of TMEM16A inhibitors.

Figure 8.

Modulation of TMEM16A in primary human lung tissue slices prevents HRSV-mediated IP-10 secretion. (A) Extrinsic IP-10 levels in the supernatants of HRSV-infected or UV-inactivated PCLS. Samples were infected for 2 hours with 106 pfu/mL and extrinsic levels of IP-10 were measured in the supernatants at 72 hpi. Individual values (dots) of six independent donors are shown. Data were compared using an unpaired Mann-Whitney one-tailed test. p<0.05 (*). (B) Immunofluorescence image of HRSV-infected PCLS inoculated with 106 pfu/mL HRSV for 2 hours. Slices were fixed 72 hpi and stained for HRSV (red), cilia (green) and DAPI (blue). (C) Extrinsic IP-10 in the supernatants of T16Ainh-A01 (10–20 µM) pretreated HRSV-infected PCLS 24 hpi. Values are the fold changes of cytokine values (normalised to pg/mg total protein) compared with respective untreated HRSV-infected tissue. Individual values (dots) of three donors are shown. Connecting lines represent data sets from the same donor. Data was analysed using an one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test p<0.05 (*) or <0.01 (**). (D) Released LDH is shown normalised to respective Triton-lysed untreated, uninfected tissue (n=3). Mean values (bars) and individual values (dots) of three donors are shown. (E) Representative western blot showing the expression of HRSV-G, HRSV-N and GAPDH (loading control) in PCLS samples treated with T16Ainh-A01. HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCLS, precision-cut lung slices; UV, ultraviolet.

We found that the treatment of PCLS with T16Ainh-A01 significantly reduced the HRSV-mediated release of IP-10 (figure 8C).36 The addition of CaCCinh-A01 led to a similar decrease in IP-10 in 2/3 donors (online supplemental figure 1Ai), yet these values did not reach statistical significance, most likely due to the lower specificity of this drug for TMEM16A. Both compounds showed no negative effects on PCLS integrity, confirmed through LDH release assays (≤30% vs Triton-lysed controls; figure 8D and online supplemental figure 1). T16Ainh-A01 treatment also led to a modest reduction in HRSV-G expression in the PCLS at 20 µM (figure 8E, representative blot) further confirmed through the assessment of HRSV-nucleoprotein (N) expression that similarly decreased following treatment with T16Ainh-A01 (20 µM). These data confirmed that T16Ainh-A01 inhibits HRSV processes, particularly HRSV-mediated IP-10 release in more physiological models of HRSV infection. Given the known proinflammatory effects of IP-10,37 these data further reveal TMEM16A modulation as a potential target to subvert HRSV-mediated lung damage.

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp001.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp002.pdf (299.8KB, pdf)

CaCCs may be required for other respiratory viruses

We finally investigated the sensitivity of IAV to TMEM16A modulation. Cells were pretreated with CaCCinh-A01, TMEM16A-specific T16Ainh-A01 and MONNA, or ribavirin, and infected for 24 hours with IAV-GFP. We found that CaCCinh-A01 led to a small but significant decrease in IAV-GFP expression (figure 9A), while MONNA had minimal effects (figure 9B). Interestingly, T16Ainh-A01 treatment potently inhibited IAV-GFP expression (65% inhibition at 30 µM) compared with solvent controls (figure 9C, E). Ribavirin also showed activity against IAV (figure 9D, E). This may infer that IAV-GFP also depends on CaCCs, although those with a different pharmacological profile to HRSV.

Figure 9.

Influenza A virus (IAV) may be dependent on CaCC modulation. (A–D) Analysis of IAV-GFP infection in A549 cells pretreated with broad CaCC inhibitor (CaCCinh-A01, 5–40 µM), TMEM16A-specific inhibitors (MONNA, 5–30 µM; T16Ainh-A01, 5–30 µM) and replication inhibitor (ribavirin, 10–80 µM). Number of GFP-expressing cells (GFP count per well) normalised to solvent-treated controls. Data are the average of three independent repeats (n=3)±SE. *P value ≤0.05. (E) Representative IncuCyte images of IAV-GFP expression in A549 cells treated with low and high concentrations of the inhibitors (CaCCinh-A01, 5 and 40 µM; T16Ainh-A01, 5 and 30 µM; MONNA 5 and 30 µM; ribavirin 10 and 80 µM). Scale bars: 300 µm. CaCC, Ca2+-activated Cl− channel.

Discussion

The CaCC TMEM16A (anoctamin 1) and CFTR are the two major secretory anion channels in airway epithelia.38 TMEM16A is upregulated during airway inflammation and asthma and has been proposed as a drug target to compensate for abrogated CFTR function in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF).23 38 In this study, we showed that the targeted inhibition of TMEM16A, but not CFTR, is of potential therapeutic benefit to HRSV sufferers through its ability to reduce viral gene expression and virus-induced IP-10 release when administered following HRSV infection. We therefore highlight TMEM16A inhibitors as a novel postexposure prophylaxis for HRSV, which may be conserved for other important respiratory virus infections.

TMEM16A is unique among Cl− channels as it comprises a dual function scramblase39 that is frequently amplified in human cancers.40 As TMEM16A silencing approaches are detrimental to cancer cell growth,26 our cell culture studies were limited to pharmacological inhibition of the Cl− functional component of the channel, which was not detrimental to cell health,26 validated in both cell lines and human PCLS. Indeed, and as previously reported, TMEM16A silencing using siRNA in our hands led to a loss of cell proliferation in A549 cells (data not shown), confirming that a reduction of TMEM16A protein but not functionality induces growth defects. An additional benefit of the pharmacological approach was that time-of-addition assays could be performed, revealing that TMEM16A-specific inhibitors maintained their inhibitory effects on HRSV when added 9 hpi, the time when viral gene expression and viral assembly/release would have already been initiated.19 This suggested that HRSV requires TMEM16A function for postentry stages of the virus life-cycle.

An unanswered question remains as to why HRSV is influenced by TMEM16A Cl− channel functionality. TMEM16A is essential for the activation of CFTR,21 however, CFTR blockers had no effect on HRSV infection, suggesting a role independent of this relationship. Similarly, the lack of NH4Cl sensitivity during any stage of the HRSV life-cycle suggested no direct role of Cl− as a counter-ion for H+ through TMEM16A.41 A finding of note was that HRSV-induced IP-10 release could be inhibited by TMEM16A blockers in PCLS. Given that proinflammatory cytokine secretion is suppressed by TMEM16A activity in human cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelia,42 this suggests that the specific effects of TMEM16A modulation on this inflammatory cytokine are likely mediated through the perturbation of HRSV-mediated processes, including virus replication and/or assembly and release. However, direct IP-10 modulation by TMEM16A may represent a limitation of this assay, which requires assessment in future studies. The organisation, composition and functions of replication factories induced by RNA viruses are generally accepted to require the recruitment of a range of host cell factors.43 Anion channels are important in a range of these viral replicase systems; CHIKV is dependent on CLIC1 that interacts with NSP3, a known component of the replicase complex12; the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 directly interacts with VP1 and VP3 of infectious bursal disease virus, a member of the Birnaviridae to stabilise RNP formation44; and CLIC-1, ClC-5 and ClC-7 silencing impede HCV replication.13 Of interest, inclusion body-associated granules (IBAGs) are key to HRSV RNA synthesis and contain viral mRNA and the viral protein M2-1, but exclude viral genomes and all necessary components required for transcription and replication (N, P and L).27 IBAGs are related to aggresomes, the sites for the accumulation of dead-end protein products in response to ER stress responses.45 Interestingly, aggresomes are known to be induced by TMEM16A activity.40 Further studies will dissect any role of TMEM16A in these HRSV-induced processes.

In summary, and for the first time, we implicate host cell Cl− conductances through TMEM16A as a key cellular process that is required during HRSV replication. The challenge is now to define the specific HRSV functionality that requires TMEM16A and regulates IP-10 release, and to assess the effectiveness of TMEM16A modulators as in vivo anti-HRSV drugs.

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp003.pdf (34.6KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Contributors: HP, EJAAT, MS, JDL, AW, JNB, CH and JM conceived the study. HP, EJAA, SEH and MA performed the experiments. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the Royal Society (Fellowship RG110306 and UF100419) and the British Lung Foundation (BLF PPRG15-17).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The use of human lung tissue was approved by the ethics committee (number 2701-2015) of the Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany. Experiments complied with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) involving human subjects. The privacy rights of human subjects were observed, and written consent was obtained from all patients. Personal data were not recorded to protect anonymity.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All free text entered below will be published.

References

- 1. Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1749–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa043951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. . Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1545–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Damasio GAC, Pereira LA, Moreira SDR, et al. . Does virus-bacteria coinfection increase the clinical severity of acute respiratory infection? J Med Virol 2015;87:1456–61. 10.1002/jmv.24210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eiland LS. Respiratory syncytial virus: diagnosis, treatment and prevention. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2009;14:75–85. 10.5863/1551-6776-14.2.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Academy of pediatrics Committee on infectious diseases: use of ribavirin in the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics 1993;92:501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rima B, Collins P, Easton A, et al. . ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Pneumoviridae. J Gen Virol 2017;98:2912–3. 10.1099/jgv.0.000959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liljeroos L, Krzyzaniak MA, Helenius A, et al. . Architecture of respiratory syncytial virus revealed by electron cryotomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:11133–8. 10.1073/pnas.1309070110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tawar RG, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, et al. . Crystal structure of a nucleocapsid-like nucleoprotein-RNA complex of respiratory syncytial virus. Science 2009;326:1279–83. 10.1126/science.1177634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hover S, King B, Hall B, et al. . Modulation of potassium channels inhibits bunyavirus infection. J Biol Chem 2016;291:3411–22. 10.1074/jbc.M115.692673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charlton FW, Hover S, Fuller J, et al. . Cellular cholesterol abundance regulates potassium accumulation within endosomes and is an important determinant in bunyavirus entry. J Biol Chem 2019;294:7335–47. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakurai Y, Kolokoltsov AA, Chen C-C, et al. . Ebola virus. two-pore channels control Ebola virus host cell entry and are drug targets for disease treatment. Science 2015;347:995–8. 10.1126/science.1258758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Müller M, Slivinski N, Todd EJAA, et al. . Chikungunya virus requires cellular chloride channels for efficient genome replication. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019;13:e0007703. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Igloi Z, Mohl B-P, Lippiat JD, et al. . Requirement for chloride channel function during the hepatitis C virus life cycle. J Virol 2015;89:4023–9. 10.1128/JVI.02946-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dobson SJ, Mankouri J, Whitehouse A. A requirement for potassium and calcium channels during the endosomal trafficking of polyomavirus virions. bioRxiv 2019:814681. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Panou M-M, Antoni M, Morgan EL, et al. . Glibenclamide inhibits BK polyomavirus infection in kidney cells through CFTR blockade. Antiviral Res 2020;178:104778. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verkman AS, Galietta LJV. Chloride channels as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009;8:153–71. 10.1038/nrd2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, et al. . Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:9345–50. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neuhaus V, Danov O, Konzok S, et al. . Assessment of the cytotoxic and immunomodulatory effects of substances in human precision-cut lung slices. J Vis Exp 2018;2018. 10.3791/57042. [Epub ahead of print: 09 May 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hillyer P, Shepard R, Uehling M, et al. . Differential responses by human respiratory epithelial cell lines to respiratory syncytial virus reflect distinct patterns of infection control. J Virol 2018;92. 10.1128/JVI.02202-17. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Aug 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li X-qing, Fu ZF, Alvarez R, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infects neuronal cells and processes that innervate the lung by a process involving RSV G protein. J Virol 2006;80:537–40. 10.1128/JVI.80.1.537-540.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benedetto R, Ousingsawat J, Wanitchakool P, et al. . Epithelial chloride transport by CFTR requires TMEM16A. Sci Rep 2017;7:12397. 10.1038/s41598-017-10910-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y, Zhang H, Huang D, et al. . Characterization of the effects of Cl− channel modulators on TMEM16A and bestrophin-1 Ca2+ activated Cl− channels. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2015;467:1417–30. 10.1007/s00424-014-1572-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kunzelmann K, Ousingsawat J, Cabrita I, et al. . TMEM16A in cystic fibrosis: activating or inhibiting? Front Pharmacol 2019;10 10.3389/fphar.2019.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Namkung W, Phuan P-W, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2011;286:2365–74. 10.1074/jbc.M110.175109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oh S-J, Hwang SJ, Jung J, et al. . MONNA, a potent and selective blocker for transmembrane protein with unknown function 16/anoctamin-1. Mol Pharmacol 2013;84:726–35. 10.1124/mol.113.087502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bill A, Hall ML, Borawski J, et al. . Small molecule-facilitated degradation of ANO1 protein: a new targeting approach for anticancer therapeutics. J Biol Chem 2014;289:11029–41. 10.1074/jbc.M114.549188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rincheval V, Lelek M, Gault E, et al. . Functional organization of cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in cells infected by respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Commun 2017;8:1–11. 10.1038/s41467-017-00655-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zheng LL, Li CM, Zhen SJ, et al. . A dynamic cell entry pathway of respiratory syncytial virus revealed by tracking the quantum dot-labeled single virus. Nanoscale 2017;9:7880–7. 10.1039/C7NR02162C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu S, Chen R, Hagedorn CH. Tannic acid inhibits hepatitis C virus entry into Huh7.5 cells. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131358. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uchiumi F, Maruta H, Inoue J, et al. . Inhibitory effect of tannic acid on human immunodeficiency virus promoter activity induced by 12-O-tetra decanoylphorbol-13-acetate in Jurkat T-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;220:411–7. 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang X-F, Dai Y-C, Zhong W, et al. . Tannic acid inhibited norovirus binding to HBGA receptors, a study of 50 Chinese medicinal herbs. Bioorg Med Chem 2012;20:1616–23. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scudieri P, Caci E, Bruno S, et al. . Association of TMEM16A chloride channel overexpression with airway goblet cell metaplasia. J Physiol 2012;590:6141–55. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.240838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reamon-Buettner SM, Niehof M, Hirth N, et al. . Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Priming of The Host Antiviral Interferon Signaling Pathway by Bronchobini® Resulting in Balanced Immune Response to Rhinovirus Infection in Mouse Lung Tissue Slices. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20. 10.3390/ijms20092242. [Epub ahead of print: 07 May 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zmora P, Molau-Blazejewska P, Bertram S, et al. . Non-human primate orthologues of TMPRSS2 cleave and activate the influenza virus hemagglutinin. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176597. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Danov O, Martin G, Greif A. Enhanced tissue damage following H1N1 infection in human Precision-Cut Lung Slices (PCLS) : American thoracic Society International Conference meetings Abstracts American thoracic Society International Conference meetings Abstracts. American Thoracic Society, 2019: A5742. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alves MP, Schögler A, Muster R, et al. . IP-10 is selectively produced in the airways upon respiratory virus infection. Eur Resp J 2013;42:3877. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gotsch F, Romero R, Friel L, et al. . CXCL10/IP-10: a missing link between inflammation and anti-angiogenesis in preeclampsia? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2007;20:777–92. 10.1080/14767050701483298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang F, Zhang H, Wu M, et al. . Calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A modulates mucin secretion and airway smooth muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:16354–9. 10.1073/pnas.1214596109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee B-C, Khelashvili G, Falzone M, et al. . Gating mechanism of the extracellular entry to the lipid pathway in a TMEM16 scramblase. Nat Commun 2018;9:1–14. 10.1038/s41467-018-05724-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H, Zou L, Ma K, et al. . Cell-specific mechanisms of TMEM16A Ca2+-activated chloride channel in cancer. Mol Cancer 2017;16:152. 10.1186/s12943-017-0720-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mellman I, Fuchs R, Helenius A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu Rev Biochem 1986;55:663–700. 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Veit G, Bossard F, Goepp J, et al. . Proinflammatory cytokine secretion is suppressed by TMEM16A or CFTR channel activity in human cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelia. Mol Biol Cell 2012;23:4188–202. 10.1091/mbc.e12-06-0424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Norrby E, Marusyk H, Orvell C. Morphogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus in a green monkey kidney cell line (Vero). J Virol 1970;6:237–42. 10.1128/JVI.6.2.237-242.1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han C, Zeng X, Yao S, et al. . Voltage-Dependent anion channel 1 interacts with ribonucleoprotein complexes to enhance infectious bursal disease virus polymerase activity. J Virol 2017;91:e00584–17. 10.1128/JVI.00584-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wileman T. Aggresomes and pericentriolar sites of virus assembly: cellular defense or viral design? Annu Rev Microbiol 2007;61:149–67. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp001.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp002.pdf (299.8KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2020-215171supp003.pdf (34.6KB, pdf)