Abstract

Climate change is affecting thermal regimes globally, and organisms relying on their environment to regulate biological processes face unknown consequences. In ectotherms, temperature affects development rates, body condition, and performance. Embryonic stages may be the most vulnerable life history stages, especially for oviparous species already living at the warm edge of their distribution, as embryos cannot relocate during this developmental window. We reared 27 epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) embryos under average summer conditions (27 °C) or temperatures predicted for the middle and end of the twenty-first century with climate change (i.e., 29 and 31 °C) and tracked growth, development, and metabolic costs both in ovo and upon hatch. Rearing sharks at 31 °C impacted embryonic growth, yolk consumption, and metabolic rates. Upon hatch, 31 °C-reared sharks weighed significantly less than their 27 °C-reared counterparts and exhibited reduced metabolic performance. Many important growth and development traits in this species may peak after 27 °C and start to become negatively impacted nearing 31 °C. We hypothesize that 31 °C approximates the pejus temperature (i.e., temperatures at which performance of a trait begin to decline) for this species, which is alarming, given that this temperature range is well within ocean warming scenarios predicted for this species’ distribution over the next century.

Subject terms: Metabolism, Climate-change impacts, Animal physiology, Ichthyology

Introduction

Ocean warming, resulting from global climate change, is already causing unprecedented changes to aquatic ecosystems worldwide1. The oceans absorb the Earth’s excess trapped heat that comes from anthropogenic emissions, and as such, sea surface temperatures are predicted to increase by as much as 4.0 °C under continued high emission scenarios1. These shifts are thought to have the most impact on tropical ecosystems where many species are adapted to narrow temperature ranges and also because seasonal temperature changes are small in comparison to those experienced in temperate zones2,3. Therefore, an organism’s ability to adapt to a change, whether by phenotypic or transgenerational plasticity, will become increasingly more important to surviving the changing conditions over the next century2. As most aquatic organisms are ectotherms, water temperatures regulate the biological and physiological processes that are crucial for survival4. Consequently, performance traits that reflect fitness (e.g., growth rates) exhibit thermal dependence, and this relationship can typically be depicted as a thermal performance curve2,5. In the context of ocean warming, establishing thermal performance curves for traits and species can help determine the suitability of future thermal habitats and help to predict both acute and chronic effects of warming on populations and ecosystems6,7.

The embryonic life stage in ectotherms represents a thermal bottleneck when it comes to climate change vulnerability8,9. Across ectotherms, embryos are generally less thermally tolerant than juveniles and non-reproducing adults. For example, embryos exhibit a narrower thermal performance curve—the difference between their maximum and minimum critical temperatures—and a lower thermal safety margin, which is the difference between their optimal temperature and their mean habitat temperature9,10. However, embryos, particularly of oviparous species, must also possess mechanisms to tolerate temperature changes throughout development because they cannot freely move and/or choose temperatures that are more favourable while in ovo11. Consequently, the mismatch between an increase in thermal vulnerability and the inability to behaviourally thermoregulate during the embryonic stages will likely have negative consequences for many aquatic ectotherm species in the face of ocean warming.

Chondrichthyan fishes (i.e., the class including sharks, rays, skates, and chimaera of which are mostly ectothermic) present a challenge in relation to ocean warming vulnerability, as many species are globally threatened (i.e., mainly from fisheries)12, poorly characterized in terms of basic life history13, have slow generation times and low reproductive output, and are logistically challenging for controlled laboratory experiments. However, these fishes have ecological, economical, and cultural significance worldwide, and require proper assessment and management, particularly with the rapidly changing marine environment14. Given that there are more than 1000 species of Chondrichthyans12, it is impractical to assume that comprehensive research investigating the effects of climate change can be conducted broadly. Therefore, we argue for a strategic focus on studies that investigate physiological tolerance limits and thresholds and to identify bioindicator species. Indeed, the indicator species concept is common in fields that include ecological and environmental monitoring to track the health of an ecosystem or to monitor the effectiveness of management15,16. However, it is less common to study an indicator species’ physiology—particularly via a thermal performance lens—for extrapolation within a taxonomic group, but that is the aim.

Because oviparous (egg-laying) chondrichthyans tend to be smaller in comparison to viviparous (live-bearing) species within this taxonomic group and are well suited to captivity, climate change impacts on in ovo growth and development have been studied in several species17–20. In fact, in ovo incubation time negatively correlates with increasing water temperatures in 28 species of sharks, skates, and chimaera that have been investigated to date11. Indeed, the maximum thermal limits for growth and development are imperative to understanding species and population level vulnerabilities. Therefore, given the similarities with regard to growth and development patterns, at least within oviparous species, an oviparous chondrichthyan may be ideal as an indicator species, especially for investigating physiological thermal tolerance with respect to climate change.

The epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum), one such small oviparous shark endemic only to the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), Australia21, has been the focus of many climate change related laboratory studies20,22–25 because this species thrives in captivity and is considered of least concern in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Criteria26. Additionally, H. ocellatum possess unique morphological and physiological traits that allow them to hunt in isolated tidal pools and survive extreme and repeated hypoxia conditions27,28. Therefore, this shark species may be resilient to challenging abiotic conditions, and as such, we propose that the H. ocellatum could serve as a conservative indicator species for chondrichthyans that are physiologically sensitive or logistically difficult to study. In other words, if epaulette sharks cannot cope with, in this case, thermal stress, how will other, less tolerant species fare?

Throughout the southern portion of their range on the GBR, H. ocellatum inhabit the reef flats where water temperatures seasonally vary, on average, from 21.7 to 27.9 °C29. While adult H. ocellatum do not use movement to behaviourally thermoregulate30, their maximum critical thermal limit (CTmax)—the highest temperature at which acute survival is possible—is between 36 and 39 °C, which although seasonally-dependent, is well beyond temperatures that are predicted for their native range during the twenty-first century due to ocean warming25. Yet, this CTmax value only applies to adult survival and over short exposure periods (hours). Moreover, this value does not likely reflect the critical temperatures for other performance traits, such as growth and development, which would span longer periods (months to years). This value also does not necessarily apply to the more vulnerable life stages, such as embryos and neonates. Indeed, processes like growth and development that are most associated with early life stages are energetically more costly than acute survival alone; therefore, such growth and development traits may exhibit a narrower thermal range and more conservative thermal limits (multiple performances-multiple optima hypothesis9,31) than other traits and in other life stages. Given that rearing embryos and neonates at 32 °C has already resulted in significant mortality in this species24, we hypothesize that the pejus temperature range (temperatures at which performance traits begin to decline32) is just below 31 °C. To determine this, we investigated the effects of rearing temperatures including 27, 29, and 31 °C on growth, development, and physiological performance traits in epaulette sharks both in ovo and until 60 days post-hatch.

Results

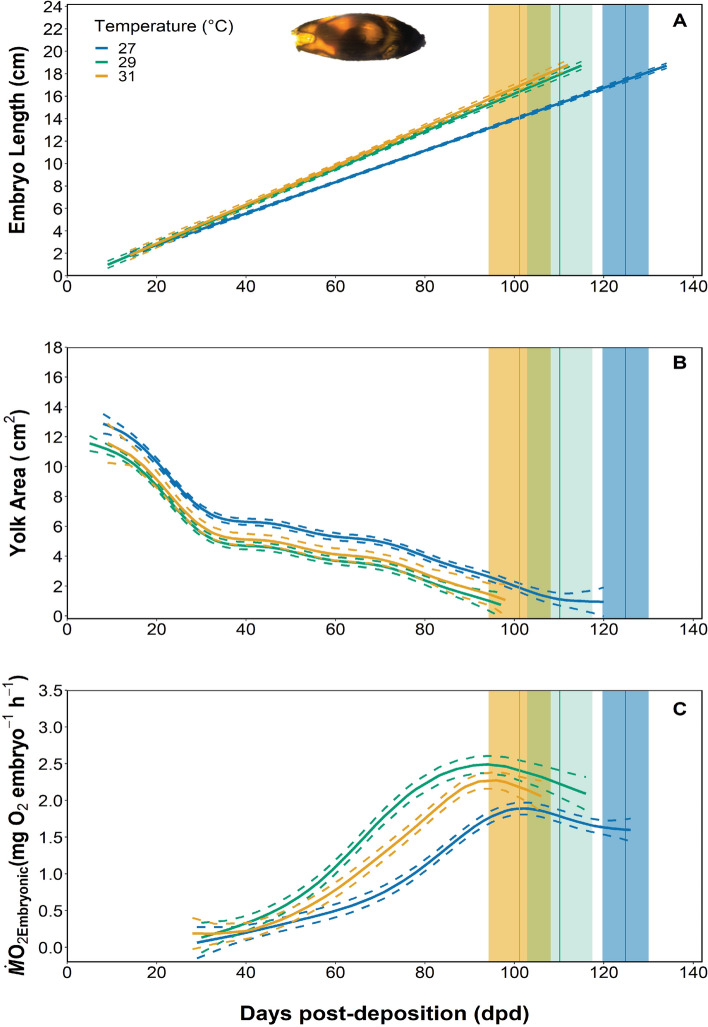

Embryonic growth and development

Twenty-seven epaulette shark embryos were reared from 7 ± 3 days post-deposition (dpd) at either 27 (n = 14), 29 (n = 7), or 31 °C (n = 6) and monitored 2–3 times weekly to track embryo length and yolk area so that growth rates could be determined. Embryonic growth rates (cm day−1) were faster for embryos reared at both 29 and 31 °C when compared to embryos reared at 27 °C, but there were no differences in growth rates for embryos reared at 29 or 31 °C (Fig. 1A, adjusted R2 = 0.85, F3,570 = 1091, P = 0.022, see S1A). Correspondingly, yolk consumption (cm2 day−1) was also significantly faster in embryos reared at both 29 and 31 °C when compared to embryos reared at 27 °C (Fig. 1B, adjusted R2 = 0.721, F3,609 = 176.10, P < 0.0001, see S1B). Embryonic oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2Embryonic), which were used as a proxy for routine metabolic rates (RMR; mg O2 embryo−1 h−1), were measured bi-weekly throughout development to assess changes in metabolic costs in relation to temperature. RMR estimates were significantly different between embryos from all temperature treatment groups; specifically, RMR was higher in embryos reared at 29 °C when compared to those reared at 27 °C but then decreased in embryos reared at 31 °C (Fig. 1C, adjusted R2 = 0.756, F3,193 = 88.23, P < 0.0001, see S1C).

Figure 1.

The growth rate (cm day−1) (A), yolk-sac consumption rate (cm2 day−1) (B), and embryonic oxygen uptake (mg O2 embryo h−1) (C), over the in ovo incubation period at 27, 29, and 31 °C. The embryonic length data were fit using a mixed linear model (S1A), and yolk-sac consumption and RMR were fit with a generalized additive model (GAM) (S1B,C). Model fits are represented by solid lines, and 95% confidence intervals are represented by dashed lines. Model fits were considered significant at α = 0.05. The vertical lines represent the mean incubation time at each temperature treatment, and the shaded boxes represent the standard error around the mean.

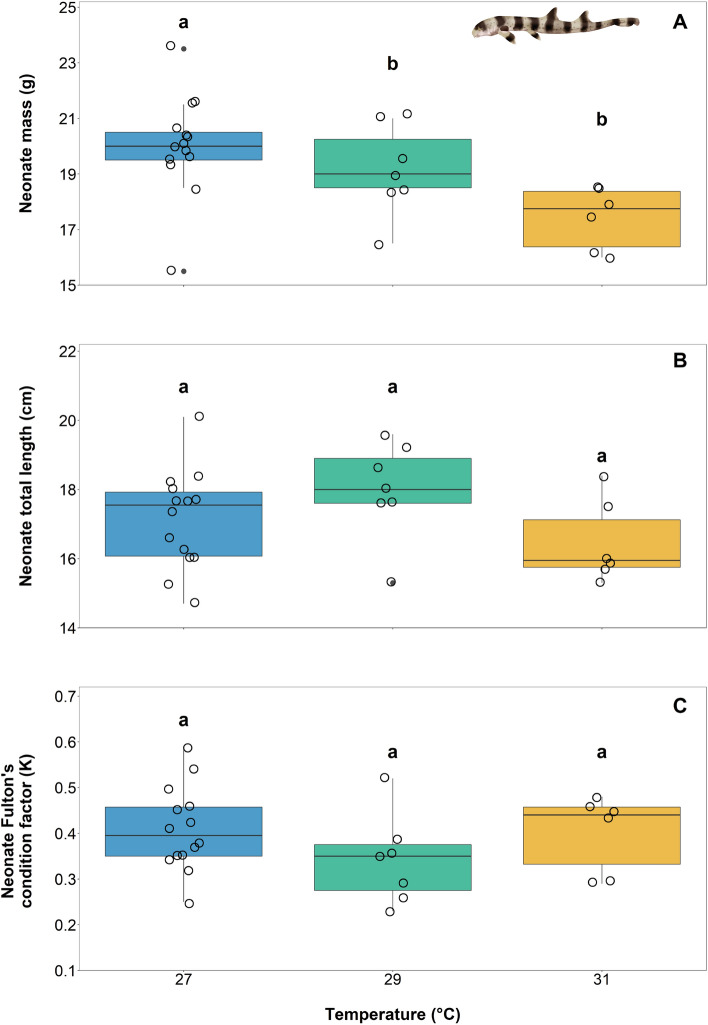

Neonate survivorship and condition

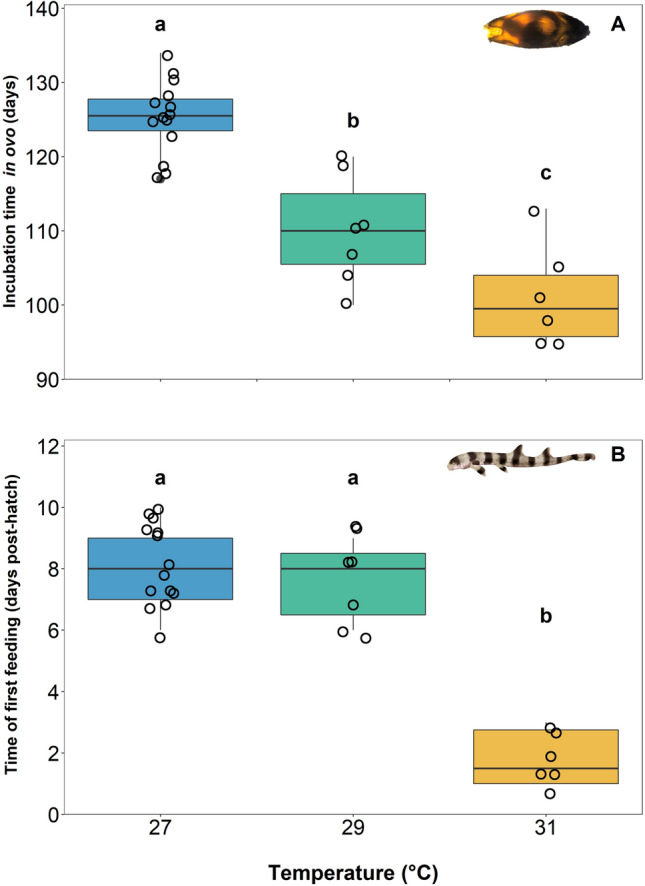

Embryonic and neonatal survival was 100% throughout the study, irrespective of rearing temperatures. All except for two sharks—one reared at 27 °C and one reared at 29 °C—hatched during the dark photoperiod hours. Hatching time was significantly impacted by temperature as well; incubation time decreased from 125 ± 5 dpd to 110 ± 7 dpd and 101 ± 7 dpd in 27, 29, and 31 °C reared embryos, respectively (Fig. 2A, ANOVA; temperature, F2,24 = 38.04, P < 0.0001; see S2A).The fastest incubation (i.e., 95 dpd) occurred in 31 °C reared embryos. Neonates were significantly lighter in mass (i.e., by 2.6 ± 0.4 g) if the embryos had been reared at 31 °C, but no differences could be detected in neonate mass when embryos were reared at 27 or 29 °C (Fig. 3A, ANOVA; temperature, F2,24 = 5.561, P = 0.01037; see S3A). However, rearing temperatures did not affect neonate length or body condition (i.e., Fulton’s condition factor) (Fig. 3B, length ANOVA; temperature, F2,24 = 1.284, P = 0.2954, see S3B; Fig. 3C, Fulton’s condition factor ANOVA; temperature, F2,24 = 2.002, P = 0.1570, see S3C). Finally, the time it took for neonates to feed exogenously for the first time was 6 ± 1 days earlier for neonates reared at 31 °C when compared to neonates reared under the other temperature treatments (Fig. 2B, ANOVA; temperature; F2,24 = 55.28, P = < 0.0001; see S2B).

Figure 2.

Mean incubation time to hatching (days) (A) and time of first exogenous feeding (post-hatch days) (B) across three treatment temperatures of 27, 29, and 31 °C. Boxes and whiskers represent the median, 25th, and 75th quartiles and 10 and 90th percentiles, respectively. The filled circles represent outliers, and open circles represent observations. Differing lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences at α = 0.05 (see S2).

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) mass (g) (A), total length (cm) (B), and Fulton’s condition factor (K) (C) at hatching across three temperature treatments of 27, 29, and 31 °C. Boxes and whiskers represent the median, 25th, and 75th quartiles and 10 and 90th percentiles, respectively. The filled circles represent outliers, and open circles represent observations. Differing lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences at α = 0.05 (see S3).

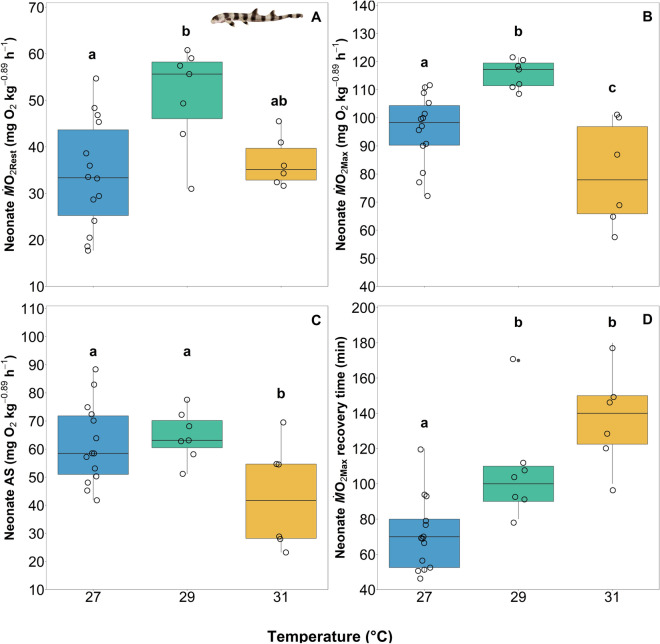

Neonate metabolic rates

Resting oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2Rest) and maximum oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2Max) were measured at 30- and 45-days post hatch, respectively, and as proxies for routine and maximum metabolic rates (RMR and MMR). In neonates reared at 29 °C, ṀO2Rest was significantly higher than in neonates reared at 27 °C, but values for neonates reared at 31 °C were not significantly different than those from the other temperature treatments (Fig. 4A; ANOVA; temperature; F2,24 = 6.25; P = 0.006531; see S4A). A similar pattern was evident with ṀO2Max; however, in neonates reared at 31 °C, ṀO2Max decreased below values observed in neonates reared under the other temperature treatments (Fig. 4B; ANOVA; temperature; F2,24 = 12.82; P = 0.0001635; see S4B). Aerobic scope (AS = ṀO2Max − ṀO2Rest) was similar in neonates reared at under 27 and 29 °C treatments but decreased in neonates reared at 31 °C (Fig. 4C; ANOVA; temperature; F2,24 = 4.53; P = 0.02142; see S4C). Finally, there was a significant relationship between temperature and the time to recover following exercise (i.e., time from ṀO2Max to ṀO2Rest); as rearing temperatures increased, recovery time increased (Fig. 4D, ṀO2Max recovery ANOVA; temperature, F2,19 = 16.727, P < 0.0001; see S4D). Neonates reared at 27 °C required an average of 71 ± 5 min to recover from exercise; whereas, neonates reared at 29 °C and 31 °C required, on average, 107 ± 7 and 138 ± 6 min, respectively (Fig. 4D). There was nearly a doubling in recovery time with a 4 °C increase in rearing temperature.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of the ṀO2Rest (mg O2 kg−0.89 h−1) (A), ṀO2Max (mg O2 kg−0.89 h−1) (B), aerobic scope (AS) (ṀO2Max—ṀO2Rest; mg O2 kg−0.89 h−1) (C), and recovery time (min) from ṀO2Max (D) for neonates across three rearing temperature treatments of 27, 29, and 31 °C. Boxes and whiskers represent the median, 25th, and 75th quartiles and 10 and 90th percentiles, respectively. The filled circles represent outliers, and open circles represent observations. Differing lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences at α = 0.05 (see S4).

Discussion

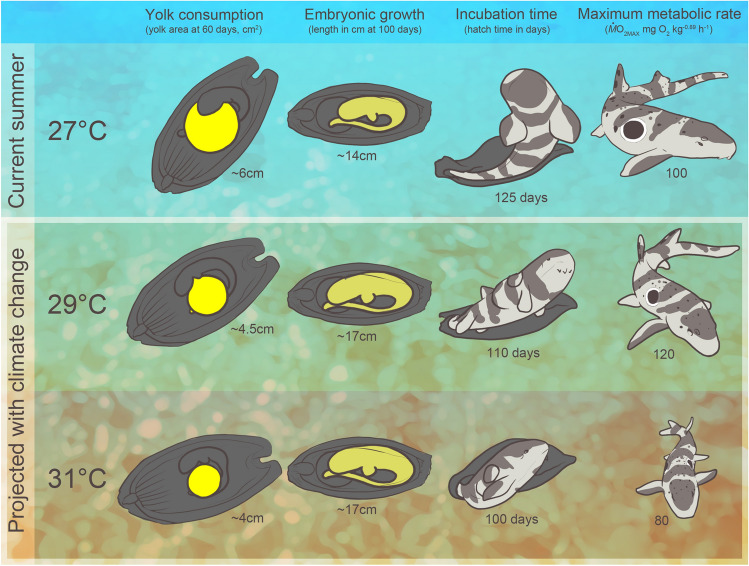

Here, we investigated how growth, development, and metabolic performance traits of embryonic and neonate H. ocellatum, a tropical, shallow-water, oviparous shark species, were affected by increased temperatures relevant to mid and end-of-century ocean warming scenarios. We hypothesized that the pejus temperature for these traits was between 29 and 31 °C, which stems from previous research reporting high mortality of H. ocellatum offspring at 32 °C24,25. Our findings support this hypothesis. While survival was unaffected, embryos that were reared under elevated temperatures (i.e., 31 °C) grew more quickly, exhibited reductions in metabolic performance, and hatched at a lighter mass than their current temperature counterparts (Fig. 5). Furthermore, upon hatch, 31 °C-reared neonates exhibited a reduction in aerobic scope, indicating thermal impairment during this vulnerable life stage. Without phenotypic or transgenerational plasticity in these key traits, our findings could foreshadow biogeographic redistribution or changes in breeding season timing with future ocean warming scenarios, which could not only apply to epaulette shark populations on the GBR but also other similar species worldwide. This information is timely—especially given the rapid succession of mass coral bleaching events and other global heatwaves since the early twenty-first century—for inclusion in vulnerability assessments for the Great Barrier Reef as well as coral reef ecosystems worldwide.

Figure 5.

A conceptual diagram highlighting some of the main findings—including the yolk consumption and growth rate at mid-development, incubation time in ovo, and estimates of maximum metabolic rates at 45 days post-hatch—across current day (27 °C) and climate-change relevant (29 and 31 °C) temperature treatments. Illustration by E. Walsh.

While H. ocellatum has been investigated within the context of climate stress and environmental change since the start of the twenty-first century, it was only recently determined that prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures could be the most detrimental to this species, especially during early life stages. Indeed, previous research on H. ocellatum demonstrated that simulated ocean acidification conditions (elevated pCO2) have little impact on early growth, development, and survivorship of embryos and neonates20 and do not affect foraging behaviour, metabolic performance, or hypoxia sensitivity of adults22,23. Moreover, this species is noted as the most hypoxia and anoxia tolerant shark species studied to date27,28. In contrast, preliminary work to this study found that, when H. ocellatum were reared at 32 °C, survival to hatching was extremely low (37.5%), neonates exhibited irregular colouration and lacked their distinct black epaulette markings, and only one 32 °C-reared neonate from the study survived beyond three days post-hatch24. Furthermore, after the remaining neonate was transitioned back to 28 °C, proper patterns and colouration still did not develop24. Juvenile H. ocellatum—at least until 171 days post-hatch—were also negatively affected when acclimated to 32 versus 28 °C. Notably, survival and growth rates were reduced, despite maintained food consumption25. Based on these findings, we focussed only on the effects of elevated temperatures and chose 31 °C as the highest temperature treatment in an effort to observe only sub-lethal, if any, effects throughout our study.

Here, embryonic growth rates were tightly coupled with faster yolk consumption rates, presumably fuelling the accelerated growth rates that were also observed (Figs. 1A,B, 5). Interestingly, growth rates were similar in animals reared at 29 and 31 °C, perhaps indicating that the pejus temperature for this trait is between these temperatures, but nearing 31 °C. Johnson et al.20 reported slower growth rates during the early stages of embryonic development that increased after embryos had progressed to one third of their total incubation time. However, our data exhibited a linear relationship that did not reflect this temporal difference in growth rates.

The 31 °C-reared neonates in this study either hatched with more internal yolk reserves or consumed internal yolk stores more quickly during their final days in ovo when compared to their lower temperature reared counterparts. For oviparous chondrichthyan embryos, in general, the yolk transfers from the external yolk sac, through a yolk stalk, and then into an internal yolk sac that feeds into the spiral intestine where it is digested to provide energy for growth and development33. When the external yolk is depleted, there remains an internal reserve that feeds the late stage embryo for a short period of time (i.e., 5–7 days in epaulette sharks) and neonates for weeks to months after hatching34. The shift from endogenous energy sources (i.e., yolk) to exogenous feeding in neonates could therefore indirectly indicate the time at which the internal yolk has been consumed, thus allowing yolk consumption rates to be calculated. External yolk-sac consumption rates for 29 and 31 °C reared embryos were similar (Fig. 1B); the last visible signs of external yolk for embryos from both treatments was around 97 ± 2 dpd but closer to 118 ± 4 dpd for 27 °C-reared embryos. As such, hatching occurred significantly earlier (101 ± 7 dpd) in 31 °C-reared animals than in 29 °C-reared animals (110 ± 7 dpd) (Fig. 1B). From these findings, we hypothesize that there is a distinct relationship between internal yolk depletion and time of hatching, which is further supported by the time of first feeding. The 31 °C-reared neonates commenced exogenous feeding significantly sooner (Fig. 2B) than their lower temperature reared counterparts. One 31 °C-reared individual consumed food only 24 h after hatching. This overall finding regarding the fast rate of energy depletion in ovo and the early timing of exogenous feeding in 31 °C-reared epaulette sharks could have clear fitness implications relative to energy use, growth, and survival over the longer term.

Our findings regarding changes in embryonic ṀO2 (ṀO2Embryonic) represent, to our knowledge, the most fine-scale (6–12 data points per embryo) data set to date for a chondrichthyan species and especially over a climate change relevant temperature range. Estimates of RMR increased as temperature increased from 27 to 29 °C, demonstrating the regulatory role temperature plays on metabolic rate for ectotherms. However, ṀO2Embryonic then declined in 31 °C-reared embryos when compared to those reared at either 29 or 27 °C. This could indicate a reduction in metabolic performance and/or a decrease in embryonic activity (tail-beating or ventilation) as an energy-saving strategy (Fig. 1C). Across treatments, ṀO2Embryonic increased to a peak at 10–20 days prior to hatching and slightly decreased thereafter. The shape of this ṀO2Embryonic curve has only been documented in one other oviparous chondrichthyan species35; all other studies report a continuous increase in RMR over development17. This decrease in O2 uptake rates during the final stages of development when the embryo has completely absorbed the external yolk sac (stage 34 from Ballard et al.33; stage 7 from Musa et al.36) could indicate crowding and mild hypoxia caused by the limited surface area for oxygen exchange across the egg case apertures and could underpin the mechanism signalling hatching.

The embryonic and neonate survival rates (i.e., 100%) throughout the present study imply that any negative effects of the rearing temperatures were only sub-lethal, at least during these early life stages. Incubation time was significantly impacted by temperature (Fig. 2A), which is a phenomenon that has been well-documented in development studies on ectothermic oviparous invertebrate and vertebrate species from both aquatic and terrestrial habitats4,11,37. Here, neonates had significantly lower mass if they were reared at 31 °C when compared to those reared at 27 °C, which supports the general hypothesis that warmer temperatures produce smaller offspring, a trend also observed across ectothermic invertebrate and vertebrate species alike38. Furthermore, the reduction in mass in 31 °C-reared animals further supports our hypothesis that expedited use of the internal yolk store may have, in part, signalled hatching. The reduction in body mass could be partially due to faster yolk consumption rates, which could compromise metabolic performance upon hatch.

At 30 days post-hatch, ṀO2Rest, which represents an estimate of SMR, increased in 29 °C-reared animals when compared to 27 °C-reared animals, and although not significant, decreased slightly in 31 °C-reared animals (Fig. 4A). A similar trend occurred for ṀO2Max, an estimate of MMR, which increased in 29 °C-reared animals when compared to 27 °C-reared animals, but was followed by a significant decrease in 31 °C-reared animals (Fig. 4B). As such, AS decreased in 31 °C-reared animals when compared to animals from the lower rearing temperatures. The increase in ṀO2Rest between 27 and 29 °C-reared animals and decrease of ṀO2Max between 29 and 31 °C animals indicates an overall reduction in metabolic performance, and that the pejus temperature likely falls between 29 and 31 °C (Figs. 4A,B, 5). The time required for 31 °C-reared animals to recover from the exercise protocol that was used to induce ṀO2Max was twice the amount of time required for 27 °C-reared animals to recover (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data indicate a decrease in the capacity for aerobic performance with elevate temperatures in neonates, which could translate to reduced survival beyond the 60 days post-hatch time period examined in this study.

Overall, we found that all metrics assessed, except length, Fulton’s condition factor, and ṀO2Rest, were negatively impacted in 31 °C-reared animals. Embryos in this treatment group hatched more quickly (Fig. 2A), were lighter in mass (Fig. 3A), exhibited reductions in metabolic performance (decreased ṀO2Max and AS; Fig. 4B,C), and required twice as long to recover from exhaustive exercise (Fig. 4D) than their lower temperature reared counterparts. Therefore, we conclude that thermal performance curves for the assessed traits for this species peak after 27 but before 31 °C, and would decrease thereafter, as supported by Gervais et al.24. While we recognize the genetic variation limitations that come with using only a single breeding pair, as was done in this study, we also note that the effects detected are, therefore, more likely solely due to temperature than genetic variability. To this end, more studies are needed, both within controlled laboratory conditions and amongst wild populations across latitudes.

Within an ecological context, epaulette sharks are distributed throughout the Great Barrier Reef in Australia and particularly occupy shallow reef flats where environmental conditions, such as dissolved oxygen and temperature, fluctuate quickly and often29. Heron Island (23.4423°S, 151.9148°E) in the southern Great Barrier Reef, has vast a reef flat where H. ocellatum are common. Given that peak egg deposition period at Heron Island is between August and November29, eggs deposited at the end of this time frame would develop on the benthos between November and February, when daily average temperatures peak at 28 °C. With mid- and end-of-century climate change predictions, it is likely that summer average temperatures could increase to upwards of 32 °C at this location. Gervais et al.25 found that juvenile H. ocellatum acclimated to 32 °C exhibited reduced growth rates despite maintaining constant food consumption rates. Moreover, these sharks behaviourally sought out warmer temperatures despite the fact that the thermal stress eventually resulted in 100% mortality. Overall, findings from Gervais et al.24,25 and the present study suggest that, under future ocean warming scenarios, H. ocellatum habitats could become too warm to support proper growth and development of embryos, neonates, and juveniles. The native range of H. ocellatum (i.e., the GBR) has already experienced heatwaves that have resulted in three widespread coral bleaching events (2016, 2017, and 202039,40). These events, although acute, could sustain throughout the developmental window of this species, thereby greatly affecting reproductive success and therefore reducing the size of that particular year class of sharks. Indeed, both acute (e.g., a heatwave, a coral bleaching event) and chronic (i.e., ocean warming) thermal stress could be detrimental to individual year classes and population stability over the long term.

Overall, we concluded that, for H. ocellatum, a species otherwise resilient to severe changes in abiotic conditions, at least those investigated in isolation (e.g., acute exposure to temperature changes, ocean acidification scenarios, and extreme hypoxia and anoxia), the pejus temperature for development is between 29 and 31 °C. Because most oviparous sharks and skates are heavily dependent on the benthos, they are unlikely or unable to undertake large movements to more ideal temperatures11,30. Therefore, we expect these species to contract their geographical range to areas where thermal conditions remain optimal, but given the importance of mesopredators, this could come at the expense of ecosystem health. Indeed, species like the epaulette shark will be the ones to observe. Ultimately, our findings suggest that, under ocean warming scenarios for the middle and end of the twenty-first century, tropical oviparous chondrichthyan species will likely be exposed to their upper thermal limits for critical activities such as growth and development, which causes concern for the future health of the ecosystems they help to support.

Materials and methods

Ethics

All experimental protocols in this study were assessed and approved by the New England Aquarium Animal Care and Use Committee ethical code (protocol #: 2017-05), and furthermore conducted in accordance with all relevant guidelines and regulations.

Embryonic growth and development

This work commenced in June 2017 and was completed in June 2019 at the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center (Quincy, MA, USA). Here, 27 epaulette shark egg cases were reared under three ecologically-relevant temperature treatments (27 °C: n = 14; 29 °C: n = 7, and 31 °C: n = 6) from 10 to 14 dpd until 60 days post-hatch. These eggs were collected from a singular breeding pair that had been maintained long term at the New England Aquarium (Boston, MA, USA). Then, all eggs were incubated in one of two 320-L aquarium systems, each fitted with a 250 L reservoir, UV sterilization, protein skimmer, two titanium heaters, and a 9:15 (d:n) hour photoperiod. Each egg case was suspended mid-water column with the proper polarity to ensure maximal success of development. All experiments were run either between June 2017 and May 2018, with a control 27 °C and experimental 29 °C temperature treatment, or between June 2018 and June 2019, where a replicated 27 °C and an experimental treatment of 31 °C were used. Temperature, salinity, ammonia, and pH were monitored daily, and nitrates and nitrites were measured weekly (Table 1).

Table 1.

The mean (± standard error) water quality parameters measured daily (*) and weekly (**) throughout the study.

| Temperature (°C)* | pH* | NH3 (ppm)* | Salinity (ppt)* | Nitrites (mg/L)** | Nitrates (mg/L)** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System 1, Round 1 | 27.0 ± 0.03 | 8.18 ± 0.0 | < 0.10 | 32.9 ± 0.16 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| System 2, Round 1 | 28.8 ± 0.04 | 8.19 ± 0.01 | < 0.10 | 32.6 ± 0.16 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 5.5 ± 0.25 |

| System 1, Round 2 | 31.0 ± 0.03 | 8.23 ± 0.02 | < 0.10 | 33.2 ± 0.22 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| System 2, Round 2 | 27.2 ± 0.07 | 8.19 ± 0.0 | < 0.10 | 32.3 ± 0.14 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.23 |

The outer most fibrous layer of the egg capsule was carefully removed using a razor blade to allow for better viewing within the capsule without any negative effects on the embryos20,41. Eggs were candled 2–3 times per week in a 10-L aquarium after allowing five minutes of habituation following transfer. This was important, as embryos of oviparous sharks are known to cease movement when there is a perceived external threat42. Images and videos of each embryo were captured using a GoPro on narrow viewing setting so that growth rates (cm day−1) and yolk-sac consumption rates (cm2 day−1) could be tracked over time. Content was corrected for fish-eye bending around the edges, and ImageJ43 was used to measure embryo length as well as yolk length, width, and area to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Embryonic oxygen uptake measurements

To quantify the metabolic cost of development in relation to temperature, oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2) of each embryo were measured in ovo using intermittent-flow respirometry. This was done every 2 weeks following the first 30 days of development because until ~ 30 days post deposition, the ṀO2 of the embryos was too small to detect while maintaining a chamber size large enough to accommodate the egg case. The whole respirometry setup comprised four glass chambers that were each 6 cm in diameter and 12 cm long (~ 339 ml volume) with baffled ends to allow even water flow. All four chambers were submerged in an 80-L water bath that received water directly from the animals’ respective aquaria to ensure identical water quality between holding conditions and test conditions. This water bath was also fitted with a standpipe so that the volume of water bath completely replenished 10 times per hour. Each chamber consisted of a flush pump (293.5 L h−1), which pumped water from the water bath, and a recirculating pump (302 L h−1) that circulated water throughout the chamber and through a glass segment consisting of an OXSP5 oxygen sensor spot connected to a fiber optic cable and a Firesting O2 system (Pyroscience, Aachen, Germany).

Embryos were carefully introduced into each respirometry chamber so that the egg case was never exposed to air. Upon transfer, chambers were covered with a small viewing window and were constantly supplied with filtered, oxygenated seawater for 2 h via the flush pump; this time period allowed embryos to habituate to the chambers following the transfer and found to be a sufficient period of time following preliminary trials31. After this 2-h habituation period, a relay timer was used to intermittently turn off the flush pump for 5, 10, or 15 min, depending on the stage of development; shorter measurement periods were used as the embryo developed. These time intervals were long enough to ensure that the decline in O2 could be detected but short enough such that O2 levels within chambers did not decrease below 80% saturation44. Following each this O2 uptake measurement period, the flush pump was turned on once again, thus returning O2 levels in the chamber water back to 100% air saturation; flush duration was always five minutes, regardless of embryo development stage. These measurement and flush cycles were repeated for 4 h (12–24 cycles depending on the measurement period) to ensure sufficient data points for each individual. After each respirometry trial, each embryo was returned to their respective holding conditions.

Respirometry chambers were also cycled empty for 30 min before and after each animal trial to account for microbial accumulation within each chamber; although, calculations demonstrated microbial respiration to be negligible (less than 2% of embryonic respiration). Respirometry chambers were also cycled with empty egg cases that had been maintained under the same conditions as the respective hatched neonates to account for the microbial respiration of each egg case; this too was also negligible (less than 3% of embryonic respiration). Oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2 in mg O2 embryo−1 h−1) were calculated as ṀO2 = SV where S represents the rate of change of O2 within the chamber, and V is the volume of the chamber44. Metabolic rates typically include a correction factor to account for body mass; however, because the embryos were maintained within the egg cases to determine incubation time to hatching, data were calculated as per whole embryo rates, similar to the protocols of Rosa et al.17. We did not correct for changes in mass using growth or yolk consumption rates, given that the former exhibited a linear and the latter a non-linear relationship (Fig. 1A,B); therefore, we could not interpolate changes in embryonic mass over development to use in ṀO2 calculations.

Neonate survivorship, condition, and oxygen uptake measurements

Within 12 h of hatching, length (cm) and mass (g) of each neonate were measured, and the Fulton’s condition factor (K = mass/length345) was calculated. Neonates were offered a mix of minced shrimp and clam, daily, after hatching to determine the time of first feeding (i.e., dph). Neonates were also provided pieces of PVC pipes for shelter. Neonate resting oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2Rest) were measured at 30 days post-hatch, as this allowed enough time post-hatch to ensure that feeding had switched from residual internal yolk stores to exogenously offered food. Prior to respirometry trials, however, neonates were fasted for 48 h to ensure they were in a post-absorptive state22. Neonates were weighed and introduced directly to their respective respirometry chambers, using the same intermittent-flow respirometry setup described for embryos, and then neonates where allowed to habituate to the chambers for 2 h. Then, the ṀO2Rest for each individual was measured using a cycle consisting of 5 min of measurement and 5 min of flushing the chambers with clean, well-aerated seawater for a period of 4 h. Trials were always executed during daytime hours. Similar to embryos, this period was determined to be the shortest trial duration to ensure the individual was in a resting non-stressed state31.

Finally, maximum oxygen uptake rates (ṀO2Max) were measured in neonates at 45 days post-hatch using a standardized 3-min chase protocol with a 1-min air exposure46. This specific protocol and time were chosen because epaulette sharks are not continuous but rather burst swimmers; after 3 min of being chased, the neonate’s response changed from avoidance to a rolling behaviour. Neonates were then immediately placed in the same intermittent flow respirometry setup that was used for embryos. The initial slope of oxygen uptake was used to calculate ṀO2Max, and then neonates remained in the chamber until oxygen uptake rates returned to ṀO2Rest levels measured for the individuals during their respective previous trial at 30 days post-hatch. A scaling exponent of 0.89 was used to correct the mass of each individual for the allometric relationship of mass and metabolic rate47,48. Finally, aerobic scope (AS) was calculated as ṀO2Max − ṀO2Rest31.

Statistical analysis

Mixed linear effects (embryo length) and generalized additive models (GAM; yolk consumption and RMR) using round (which encompasses the two rounds and systems) as a random fixed effect were applied to the data to determine if the rate of growth, yolk consumption, and oxygen uptake rates changed over time in ovo (see S1). All neonate data met all criteria of normality, non-multi-collinearity, and homoscedasticity from initial qq and residual plots and were analysed using a series of mixed linear models and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (see S2–S4). All statistical analyses were performed in RStudio (version 1.2.1335)49 where results were considered significant at α = 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors foremost thank the New England Aquarium aquarists H. Cutting, M. Lindemayer, R. Moote, C. Murphy, L. Phenix, M. Schmuck, and S. Tempesta for their invaluable logistical support throughout this project. We would additionally like to thank the numerous interns and volunteers involved with this work, particularly C. Shaeffer, and we thank the anonymous donors for financial support of this project. Finally, we acknowledge the invaluable feedback from I. Bouyoucos and two anonymous reviewers in the preparation of the manuscript and E. Walsh for the scientific illustrations.

Author contributions

This project was conceived and designed by C.W., J.R., B.B., and J.M. Data were collected and analysed by C.W., J.L., and S.V. with technical support from J.R. and B.B. All authors were involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

New England Aquarium Corporation; funding from an anonymous donor.

Data Availability

Data in this manuscript are available from the Research Data Repository (Tropical Data Hub) at JCU: 10.25903/YTXC-N035.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-79953-0.

References

- 1.Bindoff, N.L. et al. Changing ocean, marine ecosystems, and dependent communities. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (ed. Pörtner, H.O. et al.) In press (2019).

- 2.Angilletta Jr, M.J. Thermal Adaptations (ed. Angilletta Jr, M.J.) 1–18 (Angilletta, 2009).

- 3.Payne NL, et al. Temperature dependence of fish performance in the wild: Links with species biogeography and physiological thermal tolerance. Funct. Ecol. 2016;30:903–912. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillooly JF, Dodson SI. The relationship of neonate mass and incubation temperature to embryonic development time in a range of animal taxa. J. Zool. 2000;251:369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb01087.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellermann V, et al. Comparing thermal performance curves across traits: How consistent are they? J. Exp. Biol. 2019;222:193433. doi: 10.1242/jeb.193433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huey RB, et al. Predicting organismal vulnerability to climate warming: Roles of behaviour, physiology and adaptation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2012;367:1665–1679. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinclair BJ, et al. Can we predict ectotherm responses to climate change using thermal performance curves and body temperatures? Ecol. Lett. 2016;19:1372–1385. doi: 10.1111/ele.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pörtner HO, Farrell AP. Ecology: Physiology and climate change. Science. 2008;322:690–692. doi: 10.1126/science.1163156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlke FT, Wohlrab S, Butzin M, Pörtner HO. Thermal bottlenecks in the life cycle define climate vulnerability of fish. Science. 2020;369:65–70. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pörtner HO, Peck MA. Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: Towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J. Fish Biol. 2010;77:1745–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler CR, et al. Anthropogenic stressors influence reproduction and development in elasmobranch fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2020;30:373–386. doi: 10.1007/s11160-020-09604-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulvy NK, et al. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. ELife. 2014;3:e00590. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortés E. Life history patterns and correlations in sharks. Rev. Fish. 2000;8:299–344. doi: 10.1080/10408340308951115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward-Paige CA, Keith DM, Worm B, Lotze HK. Recovery potential and conservation options for elasmobranchs. J. Fish Biol. 2012;80:1844–1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindenmayer DB, Likens GE. Direct measurement versus surrogate indicator species for evaluating environmental change and biodiversity loss. Ecosystems. 2011;14:47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10021-010-9394-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siddig AAH, Ellison AM, Ochs A, Villar-Leeman C, Lau MK. How do ecologists select and use indicator species to monitor ecological change? Insights from 14 years of publication in Ecological Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016;60:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosa R, et al. Early-life exposure to climate change impairs tropical shark survival. Proc. R. Soc. B. Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20141738. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Santo V. Ocean acidification exacerbates the impacts of global warming on embryonic little skate, Leucoraja erinacea (Mitchill) J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2015;463:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pistevos JCA, et al. Ocean acidification and global warming impair shark hunting behaviour and growth. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16293. doi: 10.1038/srep16293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson MS, Kraver DW, Renshaw GMC, Rummer JL. Will ocean acidification affect the early ontogeny of a tropical oviparous elasmobranch (Hemiscyllium ocellatum)? Conserv. Physiol. 2016;4:cow003. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cow003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dudgeon CL, et al. Walking, swimming or hitching a ride? Phylogenetics and biogeography of the walking shark genus Hemiscyllium. Mar. Freshw. 2019;71:1107–1117. doi: 10.1071/MF19163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrich DDU, et al. A product of its environment: The epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) exhibits physiological tolerance to elevated environmental CO2. Conserv. Physiol. 2014;2:cou047. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cou047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinrich DDU, et al. Foraging behaviour of the epaulette shark Hemiscyllium ocellatum is not affected by elevated CO2. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015;73:633–640. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gervais C, Mourier J, Rummer JL. Developing in warm water: Irregular colouration and patterns of a neonate elasmobranch. Mar. Biodivers. 2016;46:743–744. doi: 10.1007/s12526-015-0429-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gervais CR, et al. Too hot to handle? Using movement to alleviate effects of elevated temperatures in a benthic elasmobranch, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Mar. Biol. 2018;165:162. doi: 10.1007/s00227-018-3427-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett, M.B., Kyne, P.M. & Heupel, M.R. Hemiscyllium ocellatum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T41818A68625284.10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T41818A68625284.en (2015).

- 27.Wise G, Mulvey JM, Renshaw GMC. Hypoxia tolerance in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) J. Exp. Zool. 1998;281:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980501)281:1<1::AID-JEZ1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Routley MH, Nilsson GE, Renshaw GM. Exposure to hypoxia primes the respiratory and metabolic responses of the epaulette shark to progressive hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002;131:313–321. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heupel MR, Whittier JM, Bennett MB. Plasma steroid hormone profiles and reproductive biology of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. J. Exp. Zool. 1999;284:586–594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19991001)284:5<586::AID-JEZ14>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nay, T. J. et al. Regulate or tolerate: Thermal strategy of a coral reef flat resident, the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. J. Fish Biol. 1–10. 10.1111/jfb.14616 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Clark TD, Sandblom E, Jutfelt F. Aerobic scope measurements of fishes in an era of climate change: Respirometry, relevance and recommendations. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:2771–2782. doi: 10.1242/jeb.084251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrell AP. Pragmatic perspective on aerobic scope: Peaking, plummeting, pejus and apportioning. J. Fish Biol. 2016;88:322–343. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballard WW, Mellinger J, Lechenault H. A series of normal stages for development of Schliorhinus canicula, the lesser spotted dogfish. J. Exp. Zool. 1993;267:318–336. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402670309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conrath CL, Musick JA. Reproductive biology of elasmobranchs. In: Carrier JC, Musick JA, Heithaus MR, editors. Biology of sharks and their relatives. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2012. pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodda, K.R. Chapter 5 Embryonic respiration and ventilation. In Development in the Port Jackson Shark Embryo. Thesis: University of Adelaide, 147 (2000).

- 36.Musa SM, Czachur MV, Shiels HA. Oviparous elasmobranch development inside the egg case in 7 key stages. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0206984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuo W, Moses ME, West GB, Hou C, Brown JH. A general model for effects of temperature on ectotherm ontogenetic growth and development. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2012;279:1840–1846. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkinson D. Temperature and organism size—A biological law for ectotherms? Adv. Ecol. Res. 1994;25:1–58. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes TP, et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature. 2017;543:373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skirving, W. Status of Bleaching Heat Stress on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia–2020. https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/satellite/analyses_guidance/gbr_heat_stress_event_2020_status_asof20200416.pdf (2020).

- 41.Harahush BK, Fischer ABP, Collin SP. Captive breeding and embryonic development of Chiloscyllium punctatum Muller & Henle, 1838 (elasmobranchii: Hemiscyllidae) J. Fish. Biol. 2007;71:1007–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01569.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kempster RM, Hart NS, Collin SP. Survival of the stillest: Predator avoidance in shark embryos. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:4–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svendsen MBS, Bushnell PG, Steffensen JF. Design and setup of intermittent-flow respirometry system for aquatic organisms. J. Fish Biol. 2016;88:26–50. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Froese R. Cube law, condition factor and weight-length relationships: History, meta-analysis and recommendations. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006;22:241–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2006.00805.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rummer JL, Binning SA, Roche DG, Johansen JL. Methods matter: Considering locomotory mode and respirometry technique when estimating metabolic rates of fishes. Conserv. Physiol. 2016;4:cow008. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cow008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jerde CL, et al. Strong evidence for an intraspecific metabolic scaling coefficient near 0.89 in fish. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:1166. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouyoucos IA, et al. Thermal tolerance and hypoxia tolerance are associated in blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) neonates. J. Exp. Biol. 2020;223:221937. doi: 10.1242/jeb.221937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development for R. (Version 1.1.463). http://www.rstudio.com/ (RStudio, Inc., Boston, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data in this manuscript are available from the Research Data Repository (Tropical Data Hub) at JCU: 10.25903/YTXC-N035.