Abstract

Introduction. This pilot study evaluates if an electronic nose (eNose) can distinguish patients at risk for recurrent hernia formation and aortic aneurysm patients from healthy controls based on volatile organic compound analysis in exhaled air. Both hernia recurrence and aortic aneurysm are linked to impaired collagen metabolism. If patients at risk for hernia recurrence and aortic aneurysms can be identified in a reliable, low-cost, noninvasive manner, it would greatly enhance preventive options such as prophylactic mesh placement after abdominal surgery. Methods. From February to July 2017, a 3-armed proof-of-concept study was conducted at 3 hospitals including 3 groups of patients (recurrent ventral hernia, aortic aneurysm, and healthy controls). Patients were measured once at the outpatient clinic using an eNose with 3 metal-oxide sensors. A total of 64 patients (hernia, n = 29; aneurysm, n = 35) and 37 controls were included. Data were analyzed by an automated neural network, a type of self-learning software to distinguish patients from controls. Results. Receiver operating curves showed that the automated neural network was able to differentiate between recurrent hernia patients and controls (area under the curve 0.74, sensitivity 0.79, and specificity 0.65) as well as between aortic aneurysm patients and healthy controls (area under the curve 0.84, sensitivity 0.83, and specificity of 0.81). Conclusion. This pilot study shows that the eNose can distinguish patients at risk for recurrent hernia and aortic aneurysm formation from healthy controls.

Keywords: electric nose (eNose), Aeonose, volatile organic compounds (VOC), hernia, recurrence, aneurysm

Introduction

Hernia recurrence is observed in up to 32% of the ventral hernia patients, depending on the complexity and size of the hernia, method of repair, and experience of the surgeon.1-3 Previous studies have shown that patients who develop hernia recurrences are likely to have an altered collagen type I:III ratio and abnormal collagen IV and V turnover rates, predisposing them for hernia formation and especially hernia recurrence.4,5 Similar to hernia patients, aortic aneurysm patients have equal collagen remodeling alteration.6,7 It has been well-established that patients with aortic aneurysms are at risk for hernia formation, particularly after open aortic repair.8 Hence, preventive measures, such as prophylactic mesh placement, to prevent incisional hernia formation are becoming standard practice after open aortic aneurysm repairs.8-10 The current European guideline for the closure of abdominal wall incisions also states that prophylactic mesh placements in “high-risk” patients, such as aortic aneurysm patients, can be considered.11 Identifying these high-risk patients with weak collagen before abdominal surgery remains difficult, invasive, and costly.

Breath analysis using volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath measured by an electronic nose (eNose) could potentially identify these patients in a truly noninvasive, low-cost manner. VOCs are end products of metabolic processes that are exhaled via the alveolar-capillary membrane of the respiratory tract and can be measured to identify abnormalities in metabolic processes and, subsequently, diagnose diseases.12 Exhaled breath contains hundreds of different VOCs creating a unique volatile chemical breath print for each individual.13 These VOCs can be quantitively analyzed by means of gas chromatography or mass spectrometry, though these methods are complex, costly, and time-consuming requiring trained personnel and specialized equipment. An eNose uses 3 metal-oxide sensors that analyze VOCs by redox reactions created at the metal surface of the sensors. The data from these sensors are then fed into a self-learning artificial neural network to search for patterns in the exhaled VOCs. The technique has been used successfully in previous studies for the detection of several types of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation with and without underlying pulmonary infection, asthma, sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and many more.14,15 Previous studies have shown that the eNose is most sensitive for tissues with good blood perfusion such as the brain, liver, and kidneys.5,7,16-18

In this pilot study, the eNose is used to distinguish patients with impaired collagen quality (recurrent hernia and aortic aneurysm patients) and patients with good collagen quality (healthy controls). If the eNose can be trained to distinguish these groups, it could be the first step toward preoperative identification of patients for prophylactic mesh placement.

Materials and Methods

This trial was registered in the Dutch Trial Registry under Number: NTR5954. Approval from the Medical Ethics Committee was obtained before the start of this study (Number: 164142). From February to July 2017, a 3-armed observational pilot study including patients with an (history of) aortic aneurism, patients with a (history of) ventral hernia recurrence, and healthy controls was conducted. Inclusion criteria were any patient aged between 18 and 80 years with a ventral hernia recurrence (current or in the past), or an aortic abdominal (diameter >30 mm) or thoracic aneurysm (diameter >40 mm) currently or in the past.

Exclusion criteria were the following: patients with a parastomal hernia (recurrent hernia arm only), rectus diastasis without true hernia (recurrence hernia arm only), recurrent hernias with obvious cause (eg, mesh infection or traumatic hernias), Ehlers Danlos (all types), other collagen disorders (ie, Marfan, Alport, hypochondrogenesis, Bethlem myopathy, Fuch’s dystrophy, etc), clinical hyper- or hypothyroidism, or any type of cancer at present or in the past.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study. Patients were recruited non-consecutively at allocated days from the outpatient clinic of 3 participating hospitals in the Netherlands: one local hospital (Elkerliek Hospital, Helmond), one regional teaching hospital (Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven), and one university hospital (Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht). All patients were included by a group of 3 researchers who performed inclusions at all sites.

Measurements were taken using the eNose (Aeonose), a CE (Conformité Européene)-approved eNose developed by the eNose company in Zutphen, Netherlands (Figure 1). A total of 2 different devices were used for this study. Each device had to include at least 5 positive and 5 negative cases to minimize measurement bias. For 5 minutes, patients breathe gently through a disposable mouthpiece with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter to protect the eNose from viruses and bacteria. A carbon filter filters the inhaled air, and a nose clip is used to ensure that participant breathe only through the device. The details of the eNose device, measurements, and data analysis have been described previously by Van Geffen et al,19 Kort et al,20 and Schuermans et al.15 In short, the device uses an array of nonspecific hotplate-mounted metal-oxide sensors to measure real-time conductivity changes of the sensor surface, caused by redox reactions between the metal and the exhaled VOCs. These conductivity changes are dependent on VOC composition, temperature, dynamics, and sensor surface properties. The sensors are guided through a sinusoidal temperature profile. During measurements, the first 2 minutes of breathing through the device are used for eliminating environmental differences from the lungs, followed by a 3-minute period of data recording using each of the 3 individual sensors, followed by a 4-minute recovery period during which the sensors are regenerated using clean air. All data measured by the eNose device are anonymized and sent to a central database. Using a TUCKER3-like solution, a commonly used method for principal component analysis, data are compressed to a low-dimensional vector per participant.21 These vectors together with accompanying classification are used for training the automated neural network (ANN).22 Previous studies with the eNose have shown that a minimal group size of approximately 25 patients per group is needed to train the artificial neural network reliably.19 To make sure training was on the disease and not on artefacts, cross-validation was applied using the “Leave-10%-Out” method. In that way, 10 models were trained using 90% of the data, and 10% as control to validate the outcome of the model. The 10% used for validating the ANN varied for each model. For each model, the Matthews correlations coefficient, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) are reported. The Matthews correlation coefficient can vary between −1 (perfect disagreement) and 1 (perfect agreement), 0 corresponds to a completely random (50/50) correlation. Target inclusion was set at 25 patients per group and limited at a maximum of 50 patients per group. Statistical analysis of baseline characteristics was performed using SPSS version 22, SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, released 2013).

Figure 1.

eNose device.

Results

A total of 64 patients (hernia, n = 29; aneurysm, n = 35) and 37 healthy controls were included in this study (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics). Both gender and smoking showed statistically significant differences between the patients and the healthy controls. Three patients were excluded, because they were unable to finish the measurement due to difficulty breathing through the device.

Table 1.

Demographic and Perioperative Details.

| Demographic Characteristics | Aneurysm (n= 35) | Hernia (n = 29) | Control (n = 37) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female), n | 28/7* | 20/9* | 14/23 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 73 (57-87) | 66 (45-85) | 62 (24-87) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26 (19-38) | 28 (21-43) | 24 (15-33) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 11 (31)* | 7 (24)* | 2 (5) |

| Alcohol within 48 hours | 10 (29) | 9 (31) | 14 (37) |

| Aneurism repair | 16 (46) | ||

| EVAR | 10 (29) | ||

| TEVAR | 2 (6) | ||

| Open | 4 (11) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EVAR, endovascular aneurysm repair; TEVAR, thoracic endovascular aortic repair.

Statistically significant difference compared with control group (Mann-Whitney U test P < .05).

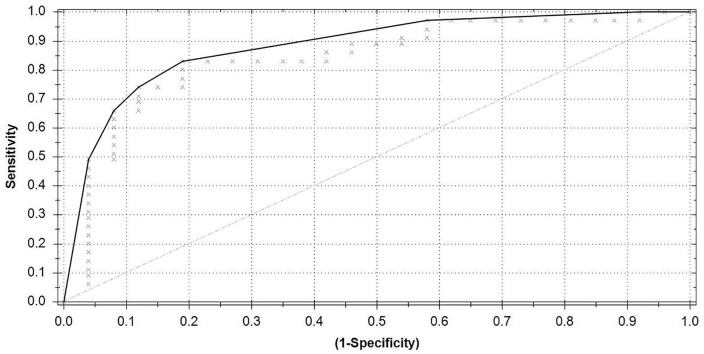

Recurrent Hernia Versus Control

For this analysis, 29 recurrent hernia patients and 37 healthy controls were included. The results of ANNs ability to differentiate between recurrent hernia patients and healthy controls are presented in a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC; Figure 2). The ROC has an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.74, Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.44, reports a sensitivity of 0.79, specificity of 0.65, with a PPV of 0.64, and a NPV of 0.80.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve recurrent hernia versus control.

Area under the curve = 0.74; Matthews correlation coefficient = 0.44.

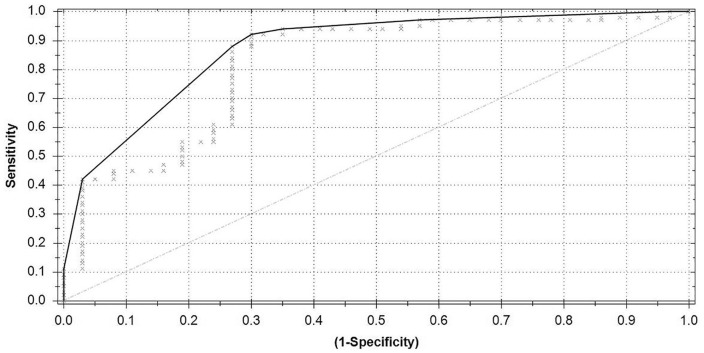

Aortic Aneurysm Versus Control

For this analysis, 35 aortic aneurysm patients and 26 controls were included. Compared with the hernia analysis, 11 control patients were excluded from the aortic aneurysm analysis to prevent measurement bias as they were measured on an eNose device that was not used for measuring aortic aneurysm patients during the study. Based on the ROC (Figure 3), an AUC of 0.84, Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.63, sensitivity of 0.83, specificity of 0.81, PPV of 0.85, and NPV of 0.78 were achieved.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve aortic aneurysm versus control.

Area under the curve = 0.84; Matthews correlation coefficient = 0.63.

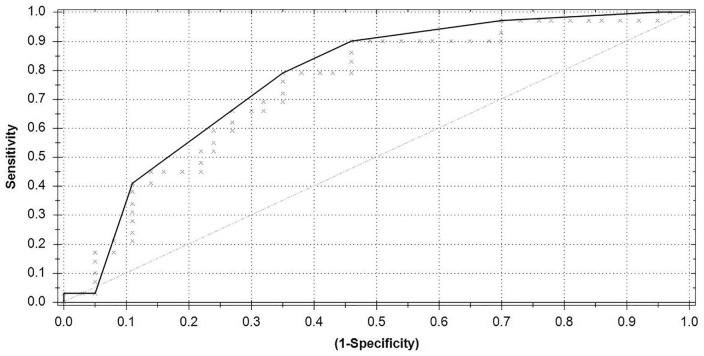

Hernia and Aneurysm Group Combined Versus Control

For this analysis, the aneurysm and hernia patients were combined into 1 group of 64 patients (29 hernia and 35 aortic aneurysm patients) and compared with the 37 healthy controls. The ROC curve (Figure 4) shows an AUC of 0.82, Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.61, sensitivity of 0.88, specificity of 0.73, PPV of 0.85, and NPV of 0.77.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve hernia and aneurysm group combined versus control.

Area under the curve = 0.82; Matthews correlation coefficient = 0.61.

Discussion

The eNose can distinguish recurrent hernia patients and aortic aneurysm patients from healthy controls. The results of this proof of concept study are the first step in identifying high-risk patients who could benefit from preventive measures such as prophylactic mesh placement after abdominal surgery.

This study describes the first application of an eNose device to distinguish patients with impaired collagen metabolism from healthy controls. Both recurrent hernia and aortic aneurysm patients are considered at risk for developing hernias, particularly after midline laparotomy.4,5 The increased risk for hernia formation in these high-risk patients has been known for some time. As evidence increases, the clinical use of prophylactic mesh placement is also increasing and becoming more and more standard in high-risk patients.11,23,24 The efficacy of prophylactic mesh placement is good although large, long-term follow-up studies are still needed. Current evidence shows minimal additional operation time, decreased incisional hernia rates (2-year follow-up) without significant increase in surgical site occurrences.9,24,25

Although preventive measures such as prophylactic mesh placement are available, identifying the high-risk patients before they undergo surgery still remains challenging.26,27 Application of an eNose in the field of ventral hernia repair and aortic aneurysms is new, though the number of eNose diagnostics has increased dramatically over the past years. Detection of colorectal cancer using eNoses has been well-established through alterations measured in both eNose as well as gas chromatography and mass spectrometry studies.28 The strength of the eNose analysis is the nonspecific measurement. This measurement, together with the automated neural network analysis, seeks for patterns in all exhaled VOCs, whereas gas chromatography and mass spectrometry primarily focus on measuring specific VOCs. Identifying VOCs linked to a particular disease is a complex process, as most VOCs are the end product of multiple metabolic processes, hence they are seldom linked to one specific pathway.13 The eNose measures the collective of the entire VOC breathprint.29,30 The ANN then “learns” to distinguish patients from controls based on pattern recognition; hence, the eNose can be applied in any type of disease that is expected to alter VOC composition, without knowing the exact metabolic changes caused by the disease. Herein lies both the strength and weakness of the eNose; as it is not possible to identify the discriminating factors, the ANN uses to categorize patients and controls. The obtained AUCs and Matthews correlation coefficients observed in this pilot study indicate that the eNose can distinguish both recurrent hernia and aortic aneurysm patients from healthy controls with some certainty. Before the eNose can be used in clinical practice, a larger prospective cohort study must evaluate if the training results obtained in this pilot study can be replicated.

Limitations

Three patients were unable to complete the eNose measurement due to shortness of breath. The eNose requires only gently breathing through the device, though the HEPA and carbon filters create an inhalation resistance, which can be problematic for patient with asthma or pulmonary comorbidity.

This pilot study has included a limited number of patients and controls, adding to the number of patients will increase the accuracy of the results obtained from the ANN, as outliers and variations in a single value can have a great effect on the ANNs ability to distinguish patients.

To train the ANN correctly, controls must be proven negative for the outcome disease. In this pilot study, control patients did not receive imaging to verify the absence of an aortic aneurysm or abdominal wall hernia. There are numerous factors that could influence VOC composition, such as age, lung function, food, exercise, sleep, smoking, alcohol consumption, and so on, all of which could not be controlled in a small pilot study. There was a statistically significant difference in smoking and gender between the control groups and the aortic aneurysm and hernia groups. Because the incidence of aortic aneurysms increases with age and has a strong male preference, both may be a confounder.

These factors will have less influence in larger follow-up studies, as the increased number of patients will ensure an equal distribution of confounders.14 Though variations in VOC composition in a small portion of the population, such as the statistically significant difference in smoking between the positive and negative groups in this study, are expected to have only limited influence as the ANN searched for one specific pattern in all positive cases. If 31% of the population has VOC alterations specific for smoking, the observed AUC of 0.84 and Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.63 cannot be based on the “smoking pattern.” The results obtained during this study were obtained using 2 hotplate metal-oxide sensors, if the results can be replicated on different eNose sensory devices (quartz microbalance, colorimetric sensors, etc) remains to be seen. Despite the previously mentioned limitations, the authors believe that the following conclusion can be drawn from this study.

Conclusion

Using the eNose and artificial neural network analysis, it was possible to distinguish recurrent hernia and aortic aneurysm patients from healthy controls. The eNose has potential as a noninvasive tool to identify patient at risk for incisional hernia formation. Before clinical application, the results of this pilot study must be replicated in a large cohort.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the eNose Company, Zutphen, Netherlands, and their supporting staff for their logistical support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Nicole D. Bouvy

Acquisition of data: Elwin H. H. Mommers, Lottie van Kooten. Simon W. Nienhuijs, Tammo S. de Vries Reilingh, Tim Lubbers, Barend M. E. Mees, Geert Willem H. Schurink

Analysis and interpretation: Elwin H. H. Mommers

Study supervision: Nicole D. Bouvy

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The eNose Company (Zutphen, Netherlands) provided the Aeonose and disposable materials for this study.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ORCID iD: Elwin H. H. Mommers https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4374-1672

References

- 1.de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, Rosman C, et al. “Components separation technique” for the repair of large abdominal wall hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deerenberg EB, Timmermans L, Hogerzeil DP, et al. A systematic review of the surgical treatment of large incisional hernia. Hernia. 2015;19:89-101. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1321-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israelsson LA, Smedberg S, Montgomery A, Nordin P, Spangen L. Incisional hernia repair in Sweden 2002. Hernia. 2006;10:258-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendavid R. The unified theory of hernia formation. Hernia. 2004;8:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen NA, Mortensen JH, Sorensen LT, et al. The collagen turnover profile is altered in patients with inguinal and incisional hernia. Surgery. 2015;157:312-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miner GH, Costa KD, Hanss BG, Marin ML. An evolving understanding of the genetic causes of abdominal aortic aneurysm disease. Surg Technol Int. 2015;26:197-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodella LF, Rezzani R, Bonomini F, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm and histological, clinical, radiological correlation. Acta Histochem. 2016;118:256-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevis PM, Windhaber RA, Lear PA, Poskitt KR, Earnshaw JJ, Mitchell DC. Randomized clinical trial of mesh versus sutured wound closure after open abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1497-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muysoms FE, Detry O, Vierendeels T, et al. Prevention of incisional hernias by prophylactic mesh-augmented reinforcement of midline laparotomies for abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2016;263:638-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieuwenhuizen J, Eker HH, Timmermans L, et al. A double blind randomized controlled trial comparing primary suture closure with mesh augmented closure to reduce incisional hernia incidence. BMC Surg. 2013;13:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muysoms FE, Antoniou SA, Bury K, et al. European Hernia Society Guidelines on the closure of abdominal wall incisions. Hernia. 2015;19:1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agapiou A, Mikedi K, Karma S, et al. Physiology and biochemistry of human subjects during entrapment. J Breath Res. 2013;7:016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amann A, Costello Bde L, Miekisch W, et al. The human volatilome: volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath, skin emanations, urine, feces and saliva. J Breath Res. 2014;8:034001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bikov A, Lazar Z, Horvath I. Established methodological issues in electronic nose research: how far are we from using these instruments in clinical settings of breath analysis? J Breath Res. 2015;9:034001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuermans VNE, Li Z, Jongen ACHM, et al. Pilot study: detection of gastric cancer from exhaled air analyzed with an electronic nose in Chinese patients. Surg Innov. 2018;25:429-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison B, Sanniec K, Janis JE. Collagenopathies-implications for abdominal wall reconstruction: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmo M, Colombo L, Bruno A, et al. Alteration of elastin, collagen and their cross-links in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:543-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baxter BT, Davis VA, Minion DJ, Wang YP, Lynch TG, McManus BM. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are associated with altered matrix proteins of the nonaneurysmal aortic segments. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:797-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Geffen WH, Bruins M, Kerstjens HA. Diagnosing viral and bacterial respiratory infections in acute COPD exacerbations by an electronic nose: a pilot study. J Breath Res. 2016;10:036001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/3/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kort S, Brusse-Keizer M, Gerritsen JW, van der Palen J. Data analysis of electronic nose technology in lung cancer: generating prediction models by means of Aethena. J Breath Res. 2017;11:026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroonenberg PM. Applied Multiway Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cartwright HM. Artificial neural networks in biology and chemistry: the evolution of a new analytical tool. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;458:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmermans L, de Goede B, Eker HH, van Kempen BJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Meta-analysis of primary mesh augmentation as prophylactic measure to prevent incisional hernia. Dig Surg. 2013;30:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jairam AP, Timmermans L, Eker HH, et al. ; PRIMA Trialist Group. Prevention of incisional hernia with prophylactic onlay and sublay mesh reinforcement versus primary suture only in midline laparotomies (PRIMA): 2-year follow-up of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:567-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachiappan S, Markar S, Karthikesalingam A, Ziprin P, Faiz O. Prophylactic mesh placement in high-risk patients undergoing elective laparotomy: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2013;37:1861-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Indrakusuma R, Jalalzadeh H, van der Meij JE, Balm R, Koelemay MJW. Prophylactic mesh reinforcement versus sutured closure to prevent incisional hernias after open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair via midline laparotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;56:120-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borab ZM, Shakir S, Lanni MA, et al. Does prophylactic mesh placement in elective, midline laparotomy reduce the incidence of incisional hernia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2017;161:1149-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Boer NK, de Meij TG, Oort FA, et al. The scent of colorectal cancer: detection by volatile organic compound analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1085-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salerno-Kennedy R, Cashman KD. Potential applications of breath isoprene as a biomarker in modern medicine: a concise overview. Wiener Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:180-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kearney DJ, Hubbard T, Putnam D. Breath ammonia measurement in Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2523-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]