Abstract

Background.

We estimated the household secondary infection risk (SIR) and serial interval (SI) for influenza transmission from HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected index cases.

Methods.

Index cases were the first symptomatic person in a household with influenza-like illness, testing influenza positive on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). Nasopharyngeal swabs collected from household contacts every 4 days were tested by rRT-PCR. Factors associated with SIR were evaluated using logistic regression.

Results.

We enrolled 28 HIV-infected and 57 HIV-uninfected index cases. On multivariable analysis, HIV-infected index cases were less likely to transmit influenza to household contacts (odds ratio [OR] 0.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1–0.6; SIR 16%, 18/113 vs 27%, 59/220). Factors associated with increased SIR included index age group 1–4 years (OR 3.6; 95% CI, 1.2–11.3) and 25–44 years (OR 8.0; 95% CI, 1.8–36.7), and contact age group 1–4 years (OR 3.5; 95% CI, 1.2–10.3) compared to 5–14 years, and sleeping with index case (OR 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.5). HIV infection of index case was not associated with SI.

Conclusions.

HIV-infection was not associated with SI. Increased infectiousness of HIV-infected individuals is likely not an important driver of community influenza transmission.

Keywords: influenza, household, transmission, HIV, South Africa

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an important risk factor for influenza-associated hospitalization and death [1, 2]. It is not known whether influenza virus transmission differs between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals, although this could potentially impact influenza virus community burden in high HIV prevalence settings. A single study from Kenya found that household contacts of HIV-infected index cases with influenza had double the risk of secondary influenza-like illness compared to contacts of HIV-uninfected index cases; however, laboratory testing for influenza was not performed on the household contacts [3]. Early studies of influenza shedding suggested that HIV-infected adults may shed influenza for longer than HIV-uninfected individuals [4, 5]. We hypothesized that HIV-infected individuals might be more likely to transmit influenza to their household contacts.

The household is an important site of influenza transmission in the community and may account for up to 30% of influenza virus transmission events [6, 7]. Factors found to be associated with increased susceptibility to influenza acquisition include younger age of the contact, underlying illness, smoking, relationship to the index case, and intensity of exposure measured by close contact with the index case such as shared bedroom or meals [8]. Factors associated with increased infectivity of the index case in previous studies include young age of the index case, higher or lower number of household contacts, and various symptoms [8].

Influenza virus circulation in South Africa is seasonal during the southern hemisphere winter [9]. In South Africa, the national HIV prevalence was 12.2% in 2012 [10], and there were an estimated 7.1 million individuals living with HIV in 2016 [11].

We implemented a study aiming to estimate the household secondary infection risk (SIR) and serial interval (SI) for influenza transmission from HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected index cases separately and to evaluate whether HIV is associated with SIR and SI.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a case-ascertained household transmission study during the 2013 and 2014 influenza seasons with enrolment of index cases from May through October each year [12]. Preliminary findings of the overall SIR and SI (not stratified by HIV status) from the 2013 influenza season have been previously described [13]. Assuming an HIV-prevalence of 40% among index cases and an SIR of 10% and 20% in contacts of HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected index cases respectively at a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a power of 0.90 we needed to enroll 80 HIV-infected and 120 HIV-uninfected index cases.

Study Population and Enrolment

The study was conducted in 2 periurban, temperate communities: Klerksdorp in the Northwest Province and Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Outpatients presenting to primary health care facilities (4 in Klerksdorp and 2 in Pietermaritzburg in 2013 and 2 at each site in 2014) were screened for influenza-like illness, defined as acute respiratory infection with measured temperature of ≥38°C or self-reported fever and cough. Eligible index cases were the first symptomatic individual in a household with 3 or more members, presenting with influenza-like illness of ≤3 days symptom duration with a positive influenza rapid diagnostic test (IRDT) from a nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal (NP/OP) swab at the time of screening subsequently confirmed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assay and consenting to HIV testing. Point of care testing was conducted using the Becton Dickinson (BD) Veritor system Flu A+B IRDTs in 2013 and the BD Directigen Flu A+B in 2014. Index cases with initially positive IRDT but subsequently negative rRT-PCR and their household contacts were withdrawn.

Household contacts included any individual who regularly ate or slept in the same household as the index case for 4 or more days a week during the exposure period (1 day before to 12 days after onset of illness in the index case). At least 70% of household members had to agree to participate for the household to be included. Household contacts were enrolled within 48 hours of index case recruitment. At the time of enrolment for index cases and contacts we collected information on demographics, medical conditions, recent and current symptoms, and type of contact between household contacts and the index case.

Follow Up

Household contacts were followed up on day 0, 4, 8, and 12 postenrolment, with collection of NP/OP swabs at home or in the clinic from all contacts regardless of illness. We extended follow-up to 12 days because we hypothesized that HIV-infected individuals might have prolonged shedding of influenza virus.

At each follow-up visit, a brief questionnaire assessing presence of symptoms was administered. Children aged ≤5 years had proxy reporting of symptoms by the primary caregiver or head of household. If a household contact was unavailable, the study teams attempted 2 revisits.

Laboratory Testing

NP/OP swab samples from index cases were collected in 10-mL Copan Universal Transport Medium system (UTM; Copan Universal, Murrieta, CA) and stored at 4°C in a refrigerator. During follow-up visits NP/OP swabs were collected from household contacts and stored in PrimeStore Molecular Transport Medium (MTM; Longhorn Vaccines and Diagnostics, Bethesda, MA) in order to obtain high-quality nucleic acids. Samples were transported to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg within the next 48 hours for testing.

Total nucleic acid extraction from all respiratory specimens was performed on MagNA Pure 96 or MagNA Pure LC instruments (Roche, Mannnheim, Germany) and tested by multiplex rRT-PCR for influenza virus A and B as well as parainfluenza virus types 1–3, respiratory syncytial virus, enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and human rhinovirus [14].

Samples testing positive for influenza A viruses were sub-typed for seasonal influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, and A(H3N2) by rRT-PCR using the CDC Influenza Virus Real-time RT-PCR [15]. The viral load of influenza was inferred from the PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values, which is inversely proportional to the PCR Ct value, that is the higher the Ct value the lower the viral load.

HIV status of index cases was ascertained by HIV testing according to national protocols at the time of enrolment using rapid HIV testing (Homemed HIV1/2 first screening test and ABON HIV1/2 Tri-Line test confirmatory test), review of laboratory-confirmed results in patient notes, or verbal reporting of a positive HIV test. A documented negative test result from the last 6 weeks was also considered valid. Household contacts were also offered HIV testing, but consent to testing was not required for study participation.

Statistical Analysis

We defined laboratory-confirmed secondary or tertiary household contacts as those with a positive result for influenza virus by rRT-PCR testing of 1 or more NP/OP specimens collected during follow-up that corresponded to the influenza type of the index case, regardless of symptoms. Proportions were compared using the Χ2 or Fisher exact test depending on numbers. The household SIR was estimated as the proportion of household contacts that had laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection. This is an overall measure of transmission in the household acknowledging that some cases may have been tertiary cases and some infections may have been acquired outside the household [8]. To minimize potential bias, for the analysis of factors associated with SIR we restricted to individuals testing influenza positive within the first 8 days of follow-up because individuals testing influenza positive after 8 days have an increased likelihood of being tertiary cases [8]. We compared the characteristics of index cases and household contacts, HIV-infected and -uninfected index cases, and factors associated with SIR using logistic regression. We controlled for characteristics of the index case and household contact in the same multivariable model. We performed a sensitivity analysis of factors associated with SIR including all enrolled contacts. Eligible contacts that refused enrolment (n = 25, 7%) were excluded from the main analysis. We performed a sensitivity analysis of the SIR in which nonenrolled eligible contacts were considered uninfected to explore the effect of this assumption.

Symptomatic household contacts were defined as individuals reporting at least 1 symptom including: fever, sore throat, cough/difficulty breathing, muscle aches, nasal congestion, diarrhea, or headache. SI was calculated as the difference between the date of first symptom onset in the index case and in the secondary case. For the analysis of SI we restricted to household contacts with symptom onset within 8 days of symptom onset in the index case. This was because we hypothesized that individuals with later symptom onset were more likely to be tertiary cases and because in our setting the mean influenza shedding duration is 7 days [16]. We evaluated factors associated with SI using Weibull accelerated failure time regression.

We accounted for within-household clustering using the Taylor-linearized variance estimation (svy Stata function) after setting households as primary sampling units. For the multivariable models we assessed all variables that were significant at P < .2 on univariate analysis, and dropped nonsignificant factors (P ≥ .05) with manual backward elimination. HIV was retained a priori as this was the main exposure of interest. Pairwise interactions were assessed by inclusion of product terms for all variables remaining in the final multivariable additive model. We conducted all statistical analyses using STATA version 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas). For each univariate analysis, we used all available case information. In the multivariable models, patients with missing data for included variables were dropped from the model.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand and KwaZulu-Natal and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with reliance on the local ethical approvals. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants or their caregivers. Participants who attended follow-up visits at the clinic were compensated for transport. There was no other compensation.

RESULTS

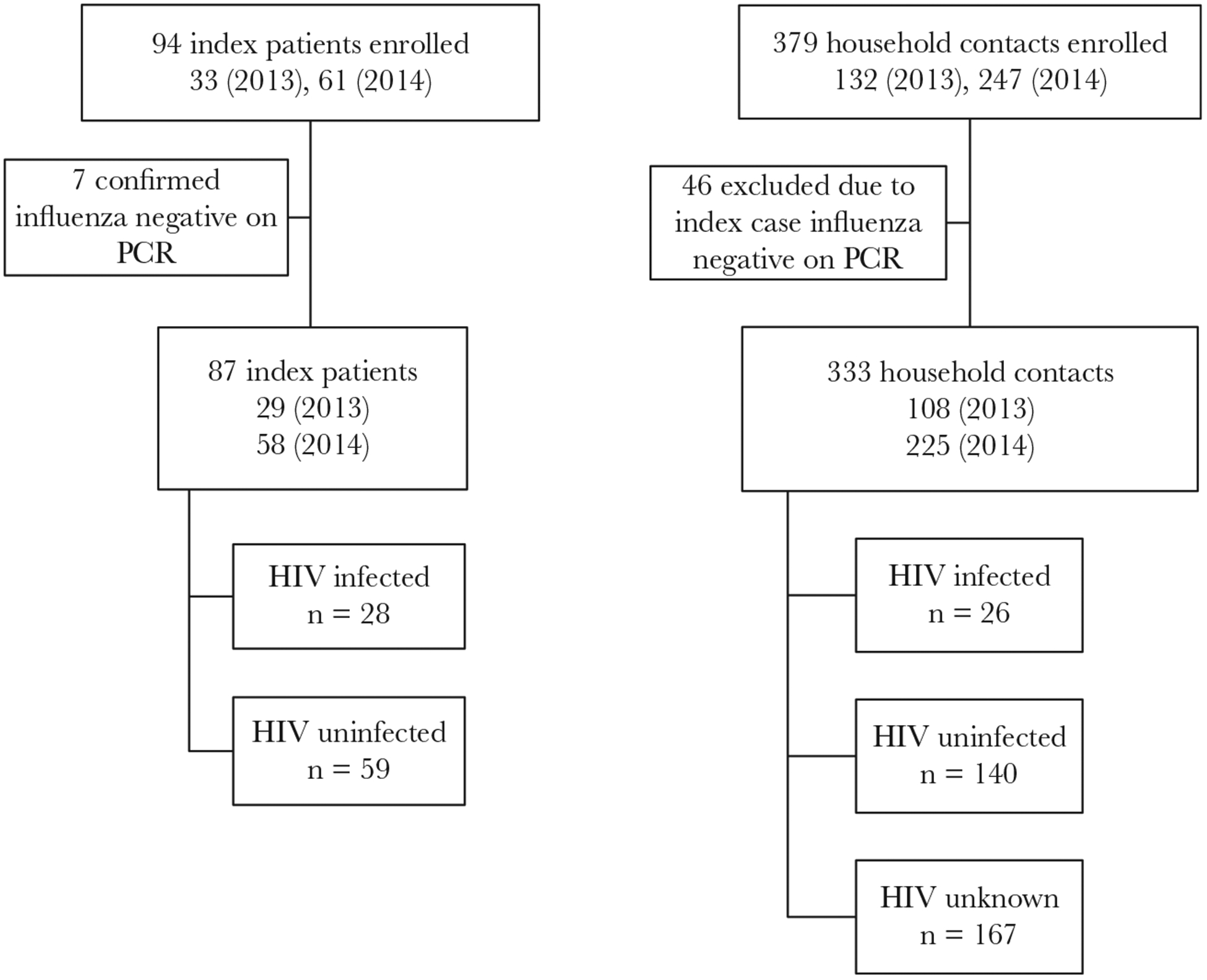

We enrolled 94 index cases based on positive IRDT results. Seven of these subsequently tested influenza negative on rRTPCR and were excluded, resulting in 87 enrolled index cases: 57 influenza A(H3N2), 17 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, 3 influenza A(unsubtyped), 10 influenza B, with 333 enrolled household contacts (Figure 1). Of the index cases, 28 (32%) were HIV-infected, 64% (18/28) of whom reported taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 53% (8/15) of those with available data had a CD4+ T cell count ≥500 cells/mm3 (Table 1). Among index cases, 23% (20/87) were aged <5 years compared to 10% (34/333) of household contacts (P = .002). Among household contacts, HIV status was available for 50% (166) of individuals, of whom 16% (26/166) were HIV-infected. A low percent of index cases (1/79, 1%) and household contacts with available data (12/271, 4%) reported receiving the influenza vaccine. All study participants were of black race. The median household size was 6 individuals including the index case (interquartile range [IQR], 3–11) and the median number of rooms per house was 4 (IQR, 2–5). On univariate analysis, compared to HIV-uninfected index cases, HIV-infected index cases were significantly more likely to be aged 25–44 years (OR, 44.2; 95% CI, 4.6–425.7) or 45–64 years (OR, 26.0; 95% CI, 2.2–304.7) compared to 15–24 years (Supplementary Table 1). Symptoms were similar in HIV-infected and -uninfected index cases.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of index cases and household contacts enrolled in Klerksdorp and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2013–2014. Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Influenza-Positive Index Cases and Their Household Contacts, Klerksdorp and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2013–2014

| Characteristic | Index Case, n/N (%) (N = 87) |

Household Contact, n/N (%) (N = 333) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | ||

| <1 | 2/87 (2) | 6/333 (2) |

| 1–4 | 18/87 (21) | 28/333 (8) |

| 5–14 | 22/87 (25) | 82/333 (25) |

| 15–24 | 14/87 (16) | 76/333 (23) |

| 25–44 | 22/87 (25) | 84/333 (25) |

| 45–54 | 9/87 (10) | 40/333 (12) |

| ≥65 | 0/87 (0) | 17/333 (5) |

| Female | 52/87 (60) | 200/309 (65) |

| Pietermaritzburg site | 45/87 (52) | 156/333 (47) |

| 2014 (vs 2013) | 58/87 (67) | 225/333 (68) |

| Alcohol usea | 13/41 (32) | 57/202 (28) |

| Smokinga | 8/41 (20) | 33/202 (16) |

| Underlying medical condition (not HIV)b | 2/87 (2) | 12/333 (4) |

| HIV-infected | 28/87 (32) | 26/140 (19)e |

| Currently taking antiretroviral therapyc | 18/28 (64) | No data |

| CD4+ T-cell count/mm3c | ||

| <200 | 2/15 (13) | No data |

| 200–500 | 5/15 (33) | |

| ≥500 | 8/15 (53) | |

| Currently taking treatment for tuberculosis | 3/79 (4) | 6/249 (2) |

| Received influenza vaccine | 1/79 (1) | 12/271 (4) |

| Household contacts only | ||

| Relationship with index case | ||

| Parent | 56/287 (20) | |

| Spouse | 7/287 (2) | |

| Child | 54/287 (19) | |

| Sibling | 58/287 (20) | |

| Other relative | 112/287 (39) | |

| Contact with index case | ||

| Share a bed | 86/312 (28) | |

| Share a cup or plate | 73/312 (23) | |

| Household-level characteristics | ||

| >3 people per room | 26/87 (30) | |

| Number in household (excluding index case) | ||

| 2–3 | 30/87 (34) | |

| 4–6 | 49/87 (56) | |

| 7+ | 8/87 (9) | |

| ≥2 secondary cases in household | 18/87 (21) | |

| Smoking exposure in homed | 7/57 (12) | |

| Home has a tap indoorsd | 18/58 (31) | |

| Soap available for hand washingd | 30/57 (53) | |

| Cook with electric stoved | 54/58 (93) |

Data missing for sex (n = 24), HIV status (n = 193), use of antiretroviral therapy (n = 36), CD4+ T-cell count (n = 39), current tuberculosis treatment (n = 92), receipt of influenza vaccine (n = 100), contact relationship with index case (n = 46), contact with index case (n = 21), smoking exposure in the home (n = 30), home has a tap indoors (n = 29), soap available for hand washing (n = 30), cook with an electric stove (n = 29).

Self reported, among individuals aged >15 years.

Asthma, other chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, liver disease, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromising conditions excluding HIV infection, neurological disease or pregnancy. Comorbidities were considered absent in cases for which the medical records stated that the patient had no underlying medical condition or when there was no direct reference to that condition.

Among HIV-infected, of individuals taking antiretroviral therapy with available data 0 had a CD4+ T-cell count <200/mm3, 4 were 200–500/mm3, and 6 were ≥500/mm3.

Information only available for households who completed a detailed household information questionnaire.

HIV-status information missing for 167 (50%) household contacts.

Overall, 88 household contacts tested influenza positive, of whom 83 had the same influenza type or subtype as the index case (SIR 25% [83/333]; 95% CI, 20%–30%). These were 54 influenza A(H3N2), 9 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, 8 influenza A(unsubtyped), and 12 influenza B. Restricting our analysis to household contacts who tested influenza positive in the first 8 days, the SIR was 23% (77/333; 95% CI, 19%–28%). Sensitivity analysis assuming 25 household members not enrolled were influenza negative gave a secondary infection risk of 22% (77/358; 95% CI, 17%–26%). On multivariable analysis, HIV-infected index cases were significantly less likely to transmit influenza (SIR 16%, 18/113) compared to HIV-uninfected index cases (SIR 27%, 59/220 adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1–0.6; Table 2). Factors associated with increased SIR were index case age group 1–4 years (aOR 3.6; 95% CI, 1.2–11.3) and 25–44 years (aOR, 8.0; 95% CI, 1.8–36.7) compared to 5–14 years, household contact age group 1–4 years (aOR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.2–10.3) compared to 5–14 years, sharing a bed with the index case (aOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.5), high viral load in index case (cycle threshold value <30) (aOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.2–6.1) and >7 people in the household (aOR, 6.1; 95% CI, 1.3–28.4) compared to 3–4 people. On sensitivity analysis including all household contacts who tested influenza positive with the same sub-type as the index case, factors associated with transmission remained unchanged (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Index Case and Household Contacts Associated With Household Secondary Infection Risk (SIR) Analysis Including Individuals Testing Influenza Positive in the First 8 Days, Klerksdorp and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2013–2014

| Characteristic | SIR,a n/N (%) | Univariate, OR (95% CI) | P | Multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index case characteristics | |||||

| Age group, y | |||||

| <1 | 0/6 (0) | Not estimated | Not estimated | ||

| 1–4 | 24/62 (39) | 2.5 (1.2–5.6) | .019 | 3.6 (1.2–11.3) | .026 |

| 5–14 | 17/86 (20) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 15–24 | 11/56 (20) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | .987 | 1.9 (0.6–6.4) | .280 |

| 25–44 | 21/85 (25) | 1.3 (0.6–3.2) | .520 | 8.0 (1.8–36.7) | .007 |

| 45–64 | 4/38 (11) | 0.5 (0.1–3.0) | .426 | 2.6(0.3–22.6) | .395 |

| ≥65 | 0/0 (0) | Not included | Not included | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 30/122 (25) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | .706 | ||

| Female | 47/211 (22) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Site | |||||

| Klerksdorp | 49/177 (28) | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | .111 | ||

| Edendale | 28/156 (18) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Year | |||||

| 2013 | 19/108 (18) | Reference | .149 | ||

| 2014 | 58/225 (26) | 1.6 (0.9–3.2) | |||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 59/220 (27) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Infected | 18/113 (16) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | .158 | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | .007 |

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 59/215 (27) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Infected, receiving | 13/77 (17) | 0.5 (0.2–1.7) | .304 | ||

| ART | 5/36 (14) | ||||

| Infected, not receiving ART | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | .034 | |||

| Non-HIV underlying illnessd | |||||

| Absent | 77/326 (24) | Not estimated | |||

| Present | 0/7 (0) | ||||

| Currently taking treatment for tuberculosis | |||||

| No | 61/281 (22) | Reference | .002 | ||

| Yes | 9/15 (60) | 5.4 (2.4–12.2) | |||

| Alcohol use | |||||

| No | 24/89 (27) | 2.8 (0.6–8.0) | .171 | ||

| Yes | 5/43 (12) | Reference | |||

| Smoking | |||||

| No | 25/108 (34) | 1.5 (0.5–7.0) | .591 | ||

| Yes | 4/24 (17) | Reference | |||

| Influenza type | |||||

| A | 71/294 (24) | Reference | .579 | ||

| B | 12/39 (31) | 1.4 (0.4–4.7) | |||

| Influenza type and subtype | |||||

| H3N2 | 52/219 (24) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | .405 | ||

| H1N1pdm09 | 12/65 (18) | Reference | Reference | ||

| A (Unsubtyped) | 2/10 (20) | 1.1 (0.2–7.9) | .921 | ||

| B | 11/39 (28) | 1.7 (0.7–6.4) | .404 | ||

| Influenza Ct value | |||||

| <30 | 64/243 (26) | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) | .036 | 2.7 (1.2–6.1) | .020 |

| ≥30 | 12/88 (14) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Pneumococcal colonization | |||||

| Yes | 37/131 (28) | 0.9 (0.4–2.4) | .909 | ||

| No | 22/75 (29) | Reference | |||

| Viral coinfectionb | |||||

| Yes | 15/64 (23) | 1.0 (0.5–2.2) | .947 | ||

| No | 62/269 (23) | Reference | |||

| Received influenza vaccine | |||||

| Yes | 0/5 (0) | Not estimated | |||

| No | 69/298 (23) | ||||

| Sore throat | |||||

| Yes | 21/135 (16) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | .032 | ||

| No | 50/173 (29) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Myalgia | |||||

| Yes | 9/64 (14) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | .176 | ||

| No | 62/244 (25) | Reference | |||

| Household contact characteristics | |||||

| Age group, y | |||||

| <1 | 3/6 (50) | 3.3 (0.6–13.6) | .095 | 1.6 (0.3–5.8) | .466 |

| 1–4 | 13/28 (46) | 2.8 (1.1–76) | .035 | 3.5 (1.2–10.3) | .021 |

| 5–14 | 19/82 (23) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 15–24 | 11/76 (14) | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | .169 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | .115 |

| 25–44 | 16/84 (19) | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | .528 | 0.8 (0.3–1.7) | .535 |

| 45–64 | 9/40 (23) | 1.0 (0.3–2.7) | .941 | 0.9 (0.3–3.0) | .832 |

| ≥65 | 6/17 (35) | 1.8 (0.6–5.5) | .294 | 2.4 (0.6–9.3) | .216 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 26/109 (24) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | .865 | ||

| Female | 46/200 (23) | Reference | |||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 38/140 (27) | Reference | .454 | ||

| Infected | 5/26 (19) | 0.6 (0.2–2.1) | |||

| Non-HIV underlying illnessd | |||||

| Absent | 75/321 (23) | Reference | .573 | ||

| Present | 2/12 (17) | 0.5 (0.1–2.9) | |||

| Alcohol usec | |||||

| No | 30/145 (21) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 10/57 (18) | 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | .647 | ||

| Smokingc | |||||

| No | 33/169 (21) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7/33 (21) | 1.1 (0.4–2.8) | .825 | ||

| Received influenza vaccine | |||||

| Yes | 2/12 (17) | Reference | .734 | ||

| No | 54/259 (21) | 1.3 (0.3–6.6) | |||

| Share a bed with the index case | |||||

| Yes | 29/86 (34) | 2.0 (1.1–3.8) | 0.021 | 2.7 (1.3–5.5) | 0.009 |

| No | 45/226 (20) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Number of people in household | |||||

| 2–3 | 12/85 (14) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 4–6 | 43/195 (23) | 1.7 (0.7–4.0) | .213 | 2.3 (0.7–7.6) | .180 |

| 7+ | 22/53 (42) | 4.3 (1.4–13.3) | .012 | 6.1 (1.3–28.4) | .022 |

| People per room | |||||

| <3 | 52/225 (23) | Reference | .358 | ||

| ≥3 | 30/108 (28) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | |||

| Number of children aged <5 years in house | |||||

| ≤2 | 64/315 (20) | Reference | <.001 | ||

| >2 | 13/18 (72) | 10.2 (7.1–14.7) |

Missing data: Out of 87 index cases included in the analysis, data were missing for alcohol use (n = 4), smoking (n = 4), current tuberculosis treatment (n = 8), received influenza vaccine (n = 8), influenza cycle threshold value (n = 1), pneumococcal colonization (n = 34), symptoms (sore throat, runny nose, headache and myalgia) (n = 7). Out of 333 household contacts included in the analysis, data were missing for contact sex (n = 24), contact HIV status (n = 167), contact alcohol use (n = 15), contact smoking (n = 15), contact influenza vaccine receipt (n = 62), contact sharing a bed with index (n = 21). There were 70 (21%) household contacts missing 1 follow-up sample, 20 (6%) missing 2 samples, and 31 (9%) missing 3 samples.

OR and P values for all variables included in the multivariable models are displayed in the 2 right hand columns of the table. No pairwise interactions were included in the multivariable models as no interaction terms were found significant. Additional factors evaluated but not found to be associated with SIR were sharing eating utensils with the index case and avoiding contact with the sick household member.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; Ct, cycle threshold; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

Secondary infection risk (SIR) = Number of secondary cases in the household/number of exposed household contacts.

Test positive on polymerase chain reaction for at least 1 of parainfluenza virus types 1–3, respiratory syncytial virus, enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus or human rhinovirus.

Among individuals aged >15 years.

Asthma, other chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, liver disease, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromising conditions excluding HIV infection, neurological disease, or pregnancy. Comorbidities were considered absent in cases for which the medical records stated that the patient had no underlying medical condition or when there was no direct reference to that condition.

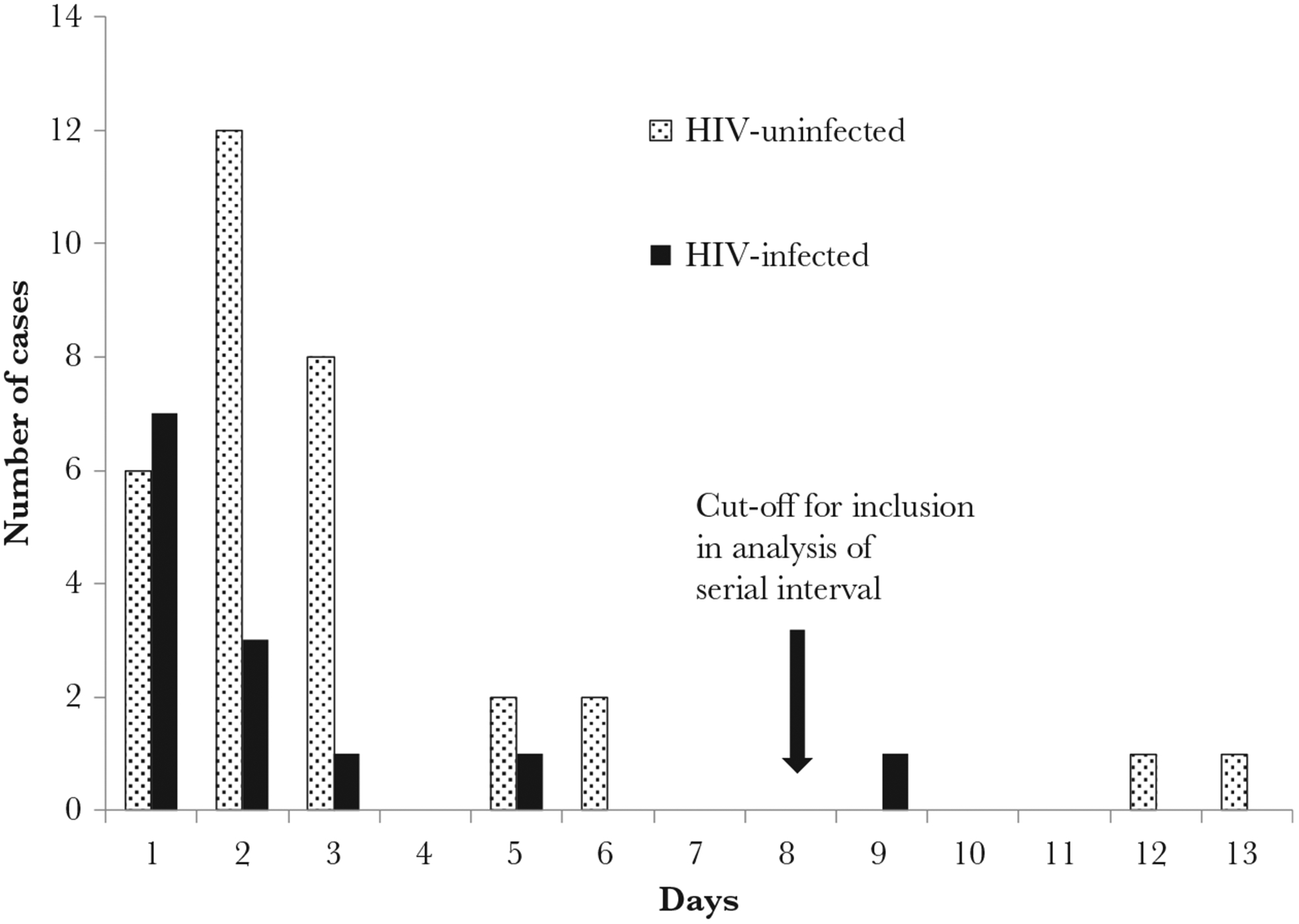

Among 213 (64%) household contacts with available symptom data, influenza-positive individuals were more likely than influenza-negative individuals to report any symptom (79%, 46/58 vs 62%, 96/155; P = .017), ≥2 symptoms (71%, 41/58 vs 50%, 78/155; P = .009), and fever and cough (48%, 28/58 vs 18%, 28/155; P < .001). Among 46 symptomatic influenza-positive contacts with available date of symptom onset, 72% [17] had symptoms prior to the first influenza positive test, 17% [8] reported symptom onset on the same day, and 11% [5] reported symptom onset after the first influenza-positive test. Among influenza-positive contacts, cough and nasal congestion were more commonly reported among children aged <5 years and muscle pain and headache among individuals aged ≥5 years (Supplementary Table 3). Forty-two individuals reported a symptom within 8 days of onset of the index case and were included in the analysis of SI (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interval between onset of symptoms in the index case and onset of symptoms in household contacts with laboratory-confirmed influenza (serial interval) by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infection status of the index case, Klerksdorp and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2013–2014 (n = 45).

The median SI in all participants was 2.3 days (range 1–6 days). On multivariable analysis, HIV infection was not associated with SI. SI was significantly shorter for index cases aged 25–44 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.1; 95% CI, 1.1–8.6) compared to 5–14 years and for household contacts aged <1 year (aHR 7.8; 95% CI, 3.6–15.2) compared to 5–14 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Serial Interval in 42 Secondary Cases With Symptom Onset Within 8 Days of the Index Case, Klerksdorp and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2013–2014

| Characteristic | Serial Interval, days, Mean ± SD (Range) | Univariate Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Multivariable Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index case characteristics | |||||

| Age group, y | |||||

| <1 | Not estimated | Not estimated | |||

| 1–4 | 2.3 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 2.2 (0.8–6.0) | .107 | 1.6 (0.5–5.6) | .422 |

| 5–14 | 2.9 ± 2.1 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 15–24 | 2.8 ± 1.7 (1–6) | 1.2 (0.3–4.0) | .804 | 1.2 (0.3–4.2) | .760 |

| 25–44 | 1.9 ± 1.1 (1–5) | 2.7 (1.1–6.4) | .033 | 3.1 (1.1–8.6) | .029 |

| 45–64 | 2.0 ± 0 (2–2) | 3.2 (1.1–9.1) | .035 | 0.6 (0.1–5.0) | .600 |

| ≥65 | Not estimated | Not estimated | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.4 ± 1.2 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 2.2 ± 1.5 (1–6) | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | .822 | ||

| Site | |||||

| Klerksdorp | 2.1 ± 1.4 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Edendale | 2.8 ± 1.3 (2–6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | .170 | ||

| Year | |||||

| 2013 | 1.7 ± 0.7 (1–3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2014 | 2.6 ± 1.5 (1–6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | .016 | ||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 2.5 ± 1.4 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | Reference | .159 |

| Infected | 1.8 ± 1.2 (1–5) | 1.8 (1.2–2.9) | .010 | 2.0 (0.7–5.7) | |

| Influenza type and subtype | |||||

| H3N2 | 2.8 ± 1.4 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| H1N1pdm09 | 1.8 ± 0.9 (1–3) | 2.6 (1.3–5.4) | .013 | ||

| B | 1.6 ± 1.3 (1–5) | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) | .001 | ||

| A (Unsubtyped) | 2.0 ± 0 (2–2) | 2.4 (1.5–4.0) | .001 | ||

| Influenza Ct value | |||||

| <30 | 2.4 ± 1.4 (1–6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | .106 | ||

| ≥30 | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Sore throat | |||||

| Yes | 3.5 ± 1.6 (2–6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | .001 | ||

| No | 1.9 ± 1.0 (1–5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Runny nose | |||||

| Yes | 2.5 ± 1.5 (1–6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | .032 | ||

| No | 1.7 ± 0.9 (1–3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Cough | |||||

| Yes | 2.3 ± 1.3 (1–6) | 0.4 (0.1–0.9) | 0.046 | ||

| No | 1.5 ± 0.7 (1–2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Household contact characteristics | |||||

| Age group, y | |||||

| <1 | 1.0 ± 0 (1–1) | 9.8 (3.5–27.4) | <001 | 7.8 (3.9–15.2) | <.001 |

| 1–4 | 2.3 ± 1.6 (1–6) | 1.3 (0.4–4.5) | .681 | 2.5 (0.4–14.8) | .303 |

| 5–14 | 2.6 ± 1.8 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 15–24 | 2.4 ± 1.4 (1–5) | 1.3 (0.4–4.0) | .631 | 3.0 (0.7–12.3) | .130 |

| 25–44 | 2.4 ± 1.2 (1–5) | 1.4 (0.5–4.0) | .506 | 3.6 (0.7–18.5) | .115 |

| 45–64 | 1.7 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 3.0 (0.9–9.3) | .062 | 8.8 (0.9–83.5) | .058 |

| ≥65 | 3.0 ± 0 (3–3) | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) | .819 | 1.3 (0.3–5.1) | .691 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.5 ± 1.6 (1–6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 2.3 ± 1.3 (1–6) | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | .677 | ||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | 2.3 ± 1.3 (1–6) | Not estimated | |||

| Infected | Not estimated |

Hazard ratios and P values for all variables included in the multivariable models are displayed in the 2 right hand columns of the table. No pairwise interactions were included in the multivariable models as no interaction terms were found significant.

Data missing for influenza Ct value (n = 2), sore throat (n = 25), runny nose (n = 25), cough (n = 25), contact sex (n = 24), and contact HIV status (n = 167)

Additional factors evaluated but not found to be associated with serial interval were as follows. Index case characteristics: non-HIV–related underlying illness, receiving tuberculosis treatment, alcohol use, smoking, pneumococcal colonization, viral coinfection, influenza vaccine receipt, and signs and symptoms (fever, myalgia, headache). Household contact characteristics: share bed with index case, alcohol use, smoking, non-HIV underlying illness, influenza vaccine receipt, number of people in the household, number of people per room, and number of children aged <5 years in the house.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Ct, cycle threshold; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to our hypothesis of increased influenza transmission from HIV-infected individuals, we found that HIV-infected individuals were significantly less likely to transmit influenza to their household contacts after adjusting for age and household size. Other factors significantly associated with influenza transmission were age of the index case and household contact, large household size, and sharing a bed with the index case. The household SIR for laboratory-confirmed influenza was high, with 1 in 4 household contacts becoming infected. Approximately 1 in 5 PCR-confirmed secondary influenza virus infections were asymptomatic.

Our estimate of SIR of 25% is within the range reported by other studies (1%–38% in a recent review) and similar to preliminary estimates of 19% from the first year of the same study [8, 13, 18]. HIV-infected individuals were significantly less likely to transmit influenza, even adjusting for age and other potential confounding factors. Tuberculosis is an example of a respiratory disease where HIV-infected individuals are less likely to transmit infection compared to HIV-uninfected individuals [19, 20]. In the case of tuberculosis, this is because the disease is less likely to form cavities in the lungs and be released in sputum. It is unclear if there may be analogous mechanisms for influenza. It is also possible that HIV-infected individuals are more likely to avoid contact with other household members or to engage in behavior such as hand washing, which may reduce transmission when ill with influenza, although we were not able to evaluate this, as we did not collect information on index case behavior. Some studies have found an association between SIR and symptoms, although findings were not consistent [8, 21–23]. We did not find symptoms to be associated with SIR in our model, nor did we find differences in symptoms between HIV-infected and -uninfected index cases. We were not able to evaluate symptoms in contacts by HIV status due to limited available data.

We had hypothesized that HIV-infected individuals would be more likely transmit influenza based on reports of increased shedding duration in this group [4, 5]. We conducted a shedding study at the same sites as our transmission study and found that influenza virus shedding duration and initial influenza viral load were similar in HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals [16]. However, in this study, HIV-infected individuals with CD4 counts ≤200 cells/mm3 shed influenza virus for longer than those with higher CD4 counts. In our study population, 64% of index cases reported taking ART and 50% with available data had a CD4 count ≥500 cells/mm3, suggesting that the majority of subjects were not severely immunosuppressed. We were not powered to assess influenza transmission stratified by level of immunosuppression, but we cannot exclude the possibility of increased transmission from severely immunosuppressed individuals. A previous study found a similar influenza virus shedding duration in HIV-infected individuals receiving ART to HIV-uninfected individuals [24].

We found that index cases aged 1–4 years were more likely to transmit influenza and household contacts aged 1–4 years were more likely to acquire infection, suggesting an important role for this age group in community influenza transmission. Several studies have found children to be more likely to transmit influenza than adults [8, 12, 25–27]. Interestingly, we also found on adjusted analysis that adults aged 25–44 years were significantly more likely to transmit influenza. This suggests that, in an African setting, young adults may play a more important role in influenza transmission than previously described. Additional factors found to be associated with influenza transmission included large household size and sharing a bed with the index case. Both large and small household size as well as close contact, such as sharing a bed, have been shown to be associated with increased transmission [8, 26, 28–30]. We also found that a low cycle threshold value of the index case, a proxy for increased nasopharyngeal viral load, was associated with increased transmission, similar to previous studies [8, 25]. We found no statistically significant difference in serial interval between HIV-infected and -uninfected index cases. Household contacts aged <1 years had a shorter serial interval, and previous studies have generally found shorter serial interval in younger individuals [31].

A strength of our approach is that all household contacts were sampled for PCR testing irrespective of symptoms. This is important as 21% of PCR-confirmed secondary cases did not report any symptoms, which is within the range found in other similar studies of 4%–28% [32]. Numbers of asymptomatically infected individuals (n = 12) were too small to allow us to evaluate predictors of asymptomatic infection in contacts. Other strengths of our study included complete HIV status information for index cases and the relatively large number of HIV-infected index cases, although we did not achieve our projected sample size.

Our study had a number of limitations. We were missing HIV status information on 50% of household contacts, therefore we were not able to assess the effect of HIV status of the household contact on acquisition of influenza virus infection. We also had missing data on CD4 counts of index cases, limiting our ability to evaluate the impact of immunosuppression on disease transmission. However, we did have information on receipt of ART for all index cases and the majority of individuals were receiving ART. It is possible that some of the infections in household contacts were acquired from outside the household leading to overestimation of the SIR. However, results of both modeling and sequencing studies from different settings indicate that the vast majority of infections in household contacts in the first week after onset in the index case will have been acquired within the household [8, 17, 25, 33]. We did identify 5 of 88 secondary infections with differing type/subtype, which is consistent with a small proportion of secondary cases acquiring infection outside the household (even with matching type/subtype). Furthermore, in some households in our study the index case may not have been the primary (ie, initial) case in the household, for example if the primary case had very mild infection that was missed, or an asymptomatic infection. Because of the short incubation period of influenza, some cases in household contacts could have been tertiary cases [8]. In addition, our approach assumes that the study population is a single homogenous population, which is an oversimplification because each household is its own population and differences between household characteristics may affect SIR [34, 35]. More complex statistical analyses have been described that take this into account and could be explored in future analyses [18, 36]. We did ask about symptoms in all household members at baseline and did not identify any recent illnesses in contacts. We performed an analysis pooling data for all influenza strains over 2 seasons. It may not be correct to assume that SIR and SI are identical for all strains and seasons, although we did not identify significant differences by these characteristics. We did not achieve our target sample size of 80 HIV-infected and 120 HIV-uninfected index cases because enrolled case numbers were lower than expected.

In conclusion, we found that HIV-infected index cases are less likely than HIV-uninfected individuals to transmit influenza virus infection to their household contacts. This suggests that even in high HIV prevalence settings, increased infectiousness of HIV-infected individuals not an important driver of community influenza transmission. In our setting, children aged 1–4 years and adults aged 25–44 years are more likely to transmit influenza. These age groups could potentially be targeted by vaccination strategies aiming to reduce community transmission. Further studies from different settings may be helpful to verify our findings and understand the mechanism behind the reduced influenza transmission from HIV-infected individuals. This should include evaluation of the impact of degree of immunosuppression and ARVs on transmission as well as evaluation of symptoms and behavior patterns of HIV-infected individuals with influenza.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

The authors thank all the individuals who kindly agreed to participate in the study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement number 5U51IP000155).

Footnotes

Presented in part: Transmission of Respiratory Viruses: From Basic Science to Evidence Based Options For Control, 19–21 June 2017, Hong Kong.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The funders had no role in design, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Potential conflicts of interest. C. C. has received grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Advanced Vaccine Initiative, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and payment of travel costs from Parexel. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S, et al. Severe influenza-associated respiratory infection in high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009–2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1766–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S, et al. Mortality amongst patients with influenza-associated severe acute respiratory illness, South Africa, 2009–2013. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0118884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judd MC, Emukule GO, Njuguna H, et al. The role of HIV in the household introductionand transmission of influenza in an urban slum, Nairobi, Kenya, 2008–2011. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:740–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstock DM, Gubareva LV, Zuccotti G. Prolonged shedding of multidrug-resistant influenza A virus in an immunocompromised patient. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:867–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ison MG, Hosoya M, Kato K, Suzuki H. Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:760–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson NM, Cummings DA, Fraser C, Cajka JC, Cooley PC, Burke DS. Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic. Nature 2006; 442:448–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao DL, Halloran ME, Obenchain VJ, Longini IM Jr. FluTE, a publicly available stochastic influenza epidemic simulation model. PLoS Comput Biol 2010; 6:e1000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang TK, Lau LLH, Cauchemez S, Cowling BJ. Household transmission of influenza virus. Trends Microbiol 2016; 24:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAnerney JM, Cohen C, Moyes J, et al. Twenty-five years of outpatient influenza surveillance in South Africa, 1984–2008. J Infect Dis 2012; 206(Suppl 1):S153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNAIDS. Country factsheets HIV/AIDS estimates: South Africa. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica 2017.

- 12.Viboud C, Boëlle PY, Cauchemez S, et al. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54:684–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyengar P, von Mollendorf C, Tempia S, et al. Case-ascertained study of household transmission of seasonal influenza - South Africa, 2013. J Infect 2015; 71:578–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pretorius MA, Madhi SA, Cohen C, et al. Respiratory viral coinfections identified by a 10-plex real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory illness--South Africa, 2009–2010. J Infect Dis 2012; 206 (Suppl 1):S159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Collaborating Centre for Influenza at CDC. CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for influenza A(H1N1). Atlanta, Georgia: WHO Collaborating Centre for influenza at CDC, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Mollendorf C, Hellferscee O, Valley-Omar Z, et al. Influenza viral shedding in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected children and adults in 2 provinces of South Africa, 2012–2014. J Infect Dis 2018; 218:1228–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papenburg J, Carbonneau J, Hamelin ME, et al. Molecular evolution of respiratory syncytial virus fusion gene, Canada, 2006–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:120–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon A, Tsang TK, Cowling BJ, et al. Influenza transmission dynamics in urban households, Managua, Nicaragua, 2012–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2018; 24:1882–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CC, Tchetgen ET, Becerra MC, et al. The effect of HIV-related immunosuppression on the risk of tuberculosis transmission to household contacts. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espinal MA, Peréz EN, Baéz J, et al. Infectiousness of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV-1-infected patients with tuberculosis: a prospective study. Lancet 2000; 355:275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carcione D, Giele CM, Goggin LS, et al. Secondary attack rate of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 in Western Australian households, 29 May-7 August 2009. Euro Surveill 2011; 16:pii: 19765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang LY, Chen WH, Lu CY, et al. Household transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1928–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamed AG, BinSaeed AA, Al-Habib H, Al-Saif H. Communicability of H1N1 and seasonal influenza among household contacts of cases in large families. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2012; 6:e25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel P, Bush T, Kojic EM, et al. Duration of influenza virus shedding among HIV-infected adults in the cART era, 2010–2011. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32:1180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsang TK, Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, et al. Influenza A virus shedding and infectivity in households. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1420–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirotsu N, Wada K, Oshitani H. Risk factors of household transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 among patients treated with antivirals: a prospective study at a primary clinic in Japan. PLoS One 2012; 7:e31519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishiura H, Oshitani H. Household transmission of influenza (H1N1–2009) in Japan: age-specificity and reduction of household transmission risk by zanamivir treatment. J Int Med Res 2011; 39:619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thai PQ, Mai le Q, Welkers MR, et al. Pandemic H1N1 virus transmission and shedding dynamics in index case households of a prospective Vietnamese cohort. J Infect 2014; 68:581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchholz U, Brockmann S, Duwe S, et al. Household transmissibility and other characteristics of seasonal oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) viruses, Germany, 2007–8. Euro Surveill 2010; 15:pii: 19483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.House T, Inglis N, Ross JV, et al. Estimation of outbreak severity and transmissibility: influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in households. BMC Med 2012; 10:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy JW, Cowling BJ, Simmerman JM, et al. The serial intervals of seasonal and pandemic influenza viruses in households in Bangkok, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177:1443–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung NH, Xu C, Ip DK, Cowling BJ. Review article: the fraction of influenza virus infections that are asymptomatic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2015; 26:862–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poon LL, Song T, Rosenfeld R, et al. Quantifying influenza virus diversity and transmission in humans. Nat Genet 2016; 48:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker NG. Analysis of infectious disease data from a sample of households. Lect Notes Monogr Ser 1991; 18:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haber M, Longini IM Jr, Cotsonis GA. Models for the statistical analysis of infectious disease data. Biometrics 1988; 44:163–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cauchemez S, Donnelly CA, Reed C, et al. Household transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus in the United States. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.