Abstract

A bi-metallic titanium–tantalum carbide MXene, TixTa(4−x)C3 is successfully prepared via etching of Al atoms from parent TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase for the first time. X-ray diffractometer and Raman spectroscopic analysis proved the crystalline phase evolution from the MAX phase to the lamellar MXene arrangements. Also, the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) study confirmed that the synthesized MXene is free from Al after hydro fluoric acid (HF) etching process as well as partial oxidation of Ti and Ta. Moreover, the FE-SEM and TEM characterizations demonstrate the exfoliation process tailored by the TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene after the Al atoms from its corresponding MAX TixTa(4−x)AlC3 phase, promoting its structural delamination with an expanded interlayer d-spacing, which can allow an effective reversible Li-ion storage. The lamellar TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene demonstrated a reversible specific discharge capacity of 459 mAhg−1 at an applied C-rate of 0.5 °C with a capacity retention of 97% over 200 cycles. An excellent electrochemical redox performance is attributed to the formation of a stable, promising bi-metallic MXene material, which stores Li-ions on the surface of its layers. Furthermore, the TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode demonstrate a high rate capability as a result of its good electron and Li-ion transport, suggesting that it is a promising candidate as Li-ion anode material.

Subject terms: Batteries, Two-dimensional materials

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) have boosted the technological advances for the last three decades, especially in mobile and transport applications as well as potential large-scale energy storage systems for electric grid applications. Extensive research and development have been dedicated to explore and improve the key components of LIBs, including negative Li-ion host graphitic anodes1. Till 1980, attempts to make a rechargeable LIB failed due to the instability of the metallic lithium as anode material. The elemental lithium is the lightest metallic element with the lowest standard reduction potential being able to reach a high energy density. However, during its cycling, lithium metal loses its performance as Li dendrites grow2, which could puncture the separator and contact the cathode electrode, resulting in an electrical short circuit that leads to the battery failure or in the worst case causing its thermal runaway, also knows as “venting with flame”. The instability of the Li-metal led researchers to develop a non-metallic electrode for lithiation, fulfilling the demanded energy requirements2–4.

The development of exfoliated layered materials, such as graphene5, oxides6,7, and chalcogenides8,9, have attracted significant attention as Li-ion anode due to their remarkable electrochemical properties to store Li-ions, reversibly. Among the lamellar materials, the recent development of metal carbides and nitrides, known as MXenes, has become one of the most promising anode materials. MXene materials belong to a novel two-dimensional family, consisting of a thin-layered arrangement of transition metal carbides and carbonitrides10. Their novel physico-chemical properties have attracted a huge attention due to its applications in energy storage11–14, electronic15–17, catalysis18–21, sensor18,22–24, medicine23–27 and others from lab to industry5,28. The development of MXene materials can be summarized in three events: (i) the invention of MAX phases in 1970, discovered by Nowotny et al. as H-phases or M2BX29; (ii) the rebirth of MAX phases in 1993 by Barsoum et al.30 who first used the formula Mn+1AXn (n = 1–4) that later evolved to the term MAX phase where “ M ”is an early transition metal (Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta); A is group13 or 14 elements (Al, Si, P, S, Ga, Ge, As, Cd, Ln, Sn, Tl, Pb) and X is Carbon and/or Nitrogen31,32 (iii) MXene material, Ti3C2, was successfully prepared in 2011 by Barsoum et al.33,34 through the immersion and exfoliation processes of Ti3AlC2 (MAX phase) in hydrofluoric acid. As the acid treatment completely removed the aluminum (A element of MAX phase), forming an exfoliated 2D lamellar crystal similar to graphene, the suffix “ene” was added to the remaining MX phase, leading to the term MXene33,34.

Especially, Bi-metallic MXenes has attracted great attention because they present unique synergistic effects on their mechanical, textural and physicochemical properties11, 16,35–39. Titanium and tantalum alloys are well known for their unique combination and exceptional set of properties in the field of powder metallurgy, nuclear industry, reprocessing applications for storing nitric acid40 and biomedical applications41–43. Titanium carbide MXenes are the most reported material to date and tantalum carbide is gaining attention in the field of theranostics, cancer therapy and few other electrochemical applications. A combination of these two MXenes offers interesting properties and a unique set of chemistry. MXenes have an advantage in comparison with graphene in tunability of material properties. In the case of graphene, the only way to tune the material properties is by its functionalization, whereas in the case of MXenes, these can be done by alloying, processing and functionalization44–47. One more key factor governing the properties of the material is defects because they have a huge role in controlling conductivity48, mechanical strength and metallic or semiconductor behaviors47,49. For example, single layer graphene with zero defects is known as a semi-metal, whereas inducing defects into its sheet generates a semiconductor behavior. Lattice imperfections are unavoidable in the case of solid-state physics and/or chemistry. Thermal defects in titanium have been recently reported47,49. Carbon vacancies are unavoidable in the MAX phases so as the MXene. Although defect-free MXenes are proving its potential in various applications, it is still unclear whether these defects would improve or deteriorate the material performance. When tantalum and titanium form an alloy compound, Ti atoms will occupy the outer layer, while Ta atoms will prefer the middle layer50. In this case, these defects become more interesting because of Ta, which has a self-oxidizing behaviour that passivates its surface, thereby providing new physicochemical properties.

MXene materials have gained great attention in battery applications for its extraordinary electrochemical properties to store Li-ions between its layered structure51 and thus these materials offer a chemically stable surface51,52. Moreover, MXene materials have been utilized as conductive support of conversion53,54 and alloying55,56 materials, which is due to its excellent mechanical and electronic properties57. Huang et al.54 have reported sandwich like Na0.23 TiO2 /Ti3C2 MXene composite. This unique sandwich morphology can relieve the strain of the electrode on cycling and deliver an enhanced carrier transport mechanism to prevent aggregation of active material. Xia et al.58 used an interfacial assembly strategy to assemble Si porous nanospheres on titanium carbide MXene sheets; improving the electrode’s electron transport and stability. The MXene surface groups enable strong interaction with Si porous nanoparticles and develop pseudocapacitive behaviour, which can be advantageous for Li-ion storage. The Si-MXene assembly delivered an 1154 mAh/g at 0.2 A/g with good cycling stability. Meng et al.59 have explored black phosphorous quantum dots with Ti3C2 MXene as battery electrodes with enhanced pseudocapacitive capability. This interface enables high electrical conductivity, relieving stress on cycling with enhanced charge adsorption, and efficient interfacial electron transfer. The MXene composite electrode delivered 910 mAh/g at 100 mA/g with long cycling stability over 2400 cycles. Here, we report the preparation of a lamellar bi-metallic titanium–tantalum carbide MXene, TixTa(4−x)C3 (where x = 2), with expanded interlayer spacing, as promising Li-ion host material with high capacity, excellent rate capability and long-term cyclability. The raw TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene was synthesized through an etching process with HF, in which Al atoms were extracted from TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase (where x = 2), promoting its structure delamination concurrently. The layered TixTa(4−x) C3 MXene displayed an expanded interlayer d-spacing of 3.37 Å with a layer thickness of 0.325 nm, which allows reversible Li-ion storage between its laminates. Therefore, TixTa(4−x) C3 delivered a remarkable reversible high specific discharge capacity of about 459 mAhg−1 at an applied C-rate of 0.5 °C with a coulombic efficiency of around 99% after 200 cycles, as well as an excellent rate capability.

Materials characterization

X-ray diffractograms were obtained using a Bruker D8 XRD operated in Bragg–Brentano geometry with fixed slits (at room temperature). The vibrational modes were recorded using a Raman spectrometer (Horiba Scientific) with a 532 nm green laser. Morphological pictograms were recorded using supra-55 FE-SEM (Carl Zeiss) and a G2-20 TWIN TEM (FEI-TECNAI), respectively. High-resolution TEM images were recorded at 200 kV accelerating voltage integrated with a Gatan Orius CCD camera. Elemental composition was analyzed using a MultiLab 2000 XPS spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). All the elemental spectra were referenced with respect to the carbon (C1s—284.6 eV). Thermogravimetric Analysis was carried out using TA Instruments SDTQ600.

Electrochemical evaluation

The bi-metal TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene nanoparticles’ electrochemical performance as Li-ion host material was analyzed using potentiostatic cyclic voltammetry and galvanostatic charge–discharge cycling as per our earlier reports6,60,61. First, TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene powder was mixed with conductive additive (super P carbon) and binder (PVDF) with a mass ratio of 80:10:10 in solvent (NMP). The resultant anode slurry was uniformly coated on a Cu foil and dried in vacuum at 80 °C for 24 h. The resultant anode films was punched out (12 mm of diameter).The electrochemical testing was carried out using coin-type cells 2032 in half-cell configuration with a Li and Celgard 2500 disks as counter electrode and separator, respectively, and 1.0 M LiPF6 electrolyte (EC: DEC—1:1).

Results and discussion

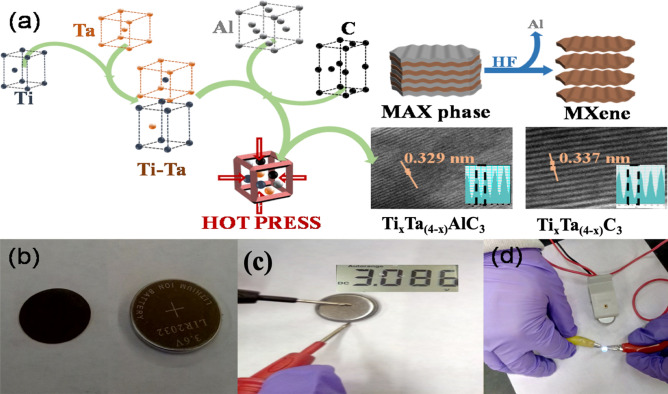

MXene compounds are traditionally prepared via a three-step process. First, a ball-milling is carried out to mix all the components efficiently. Then, a hot press treatment at a high temperature is performed to obtain a homogeneous MAX phase. Finally, an etching process with hydrofluoric acid is implemented to remove the “A” component of the MAX phase, giving a lamellar material, MXene. However, the preparation of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene involves an extra-initial step that consists in the formation of a TiTa alloy through ball-milling as given in (Fig. 1a). The bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene was used as active materials of the working electrode in a half-cell battery (Fig. 1b) that gives an open-circuit voltage (OCV) > 3.0 V vs. Li/Li+ after resting 24 h (Fig. 1c), which demonstrated its potential as anodic electrode turning on a white led (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

(a) A schematic illustration of the method followed to prepare bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene, (b) MXene working electrode and its respective coin cell; tests of (c) open circuity voltage and (d) LED emitting white light using our MXene half-cell.

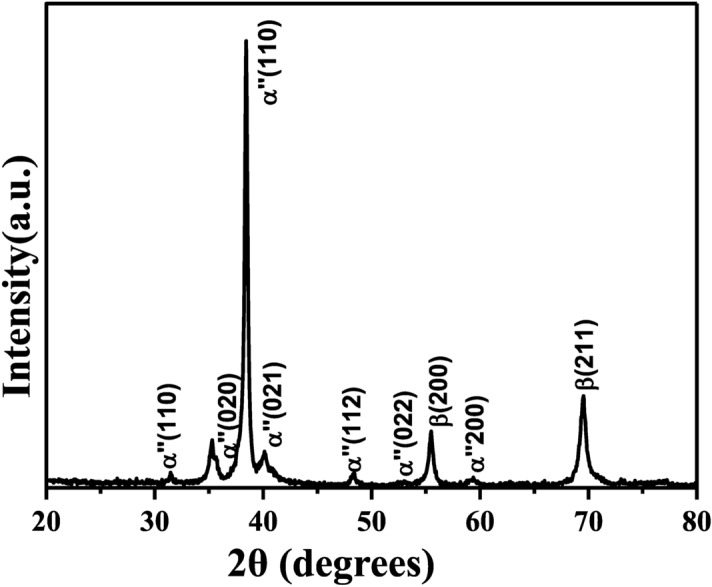

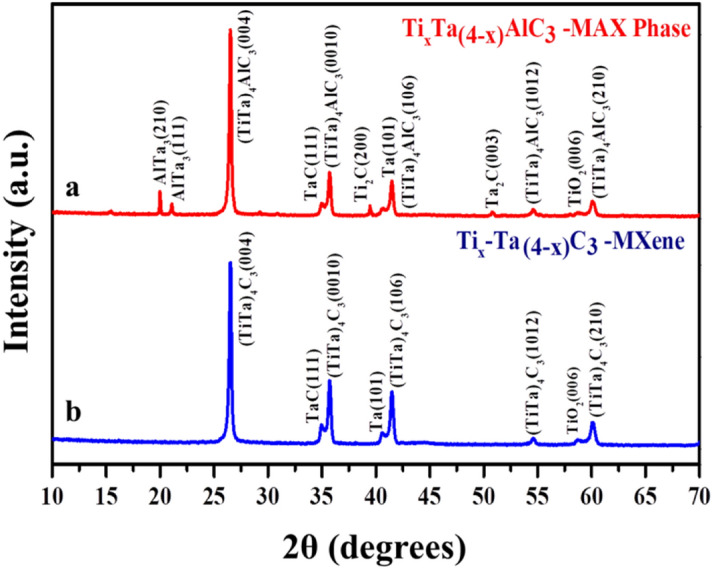

Figure 2 shows the XRD pattern of alloyed titanium and tantalum (TiTa), which were found out to be in the hexagonal phase matching with the JCPDS card number of 00-044-1294. The XRD pattern of the TiTa alloys, are narrow/sharp confirming micron sized particles. The major peaks in the system are martensitic α″ and minor being β (austenite phase, JCPDS card number of 00-044-1288), where α″ is inversely proportional to the particle size and β is directly proportional i.e. the particles with a smaller size, the XRD pattern will have dominated martensitic α″ peaks and minor β peaks62. In our case, there is also a major α″ for the alloyed TiTa. The powder XRD pattern of the TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase is shown in Fig. 3. The XRD peaks of the synthesized sample are mainly ascribed to tantalum-titanium aluminum carbide with small traces of AlTa3, Ta2O, and TiO2. The obtained XRD pattern was in phase with the earlier reports matching with the tantalum aluminium carbide (ICSD-156383)27,32. A shift in 2θ was also observed because of the double ordered metal atoms. The synthesised samples were in hexagonal crystal system, which can also be seen in SAED pattern obtained from the TEM analysis as given in Fig. S3. Furthermore, by alloying Ti with Ta, the elemental Ti has a lower melting point than the Ta but as the particle is in micron size, they can be sintered together. In case of lower temperatures, Ti and Ta rich zones can appear in the material, but as MAX phases require a high temperature of 1500 °C, at this condition an interdiffusion of Ti and Ta atoms occurs at their interphase due to Kirkendall effect63,64. As there is a difference between Ti and Ta diffusion coefficients, there is an improper transport of atoms from one side of the interphase to the other, resulting in a partial diffusion and the formation of defects as vacancies or porosity in the zone, where the atoms move out64. Consequently, there is a downshift of the XRD peaks in the case of the MXene phase in comparison with its parental MAX, as a result of an increase in the C lattice parameter from after HF etching32,39,65. The minor reflections between 5° and 25° disappeared in the case of MXene phase because of the non-standard orientation of the sample (vertical orientation assuming based on the experimental data by Ghidiu et al.66). Also, the contamination peaks66 ascribed to AlTa3 and Ta2O are not observed as they are removed during the etching and washing processes.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern of the titanium and tantalum alloy.

Figure 3.

X-Ray Diffraction pattern of the synthesized bi-metallic (a) TixTa(4–x)AlC3 MAX phase, red color; and (b) TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene, blue color.

The Raman spectrum of the synthesized bi-metallic TixTa(4-x)AlC3 MAX phase and its corresponding Al etched TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene phase are given in (Fig. S1). The Raman active modes are given from ω3 to ω10 because of TiTa, Al, and C32,67–69. The modes ω3, ω6, ω9 are due to the intermediate layer element “Aluminum”, which are suppressed due to the exchange of Al with its lower atoms (O, F, OH) or its removal during the HF etching processes.

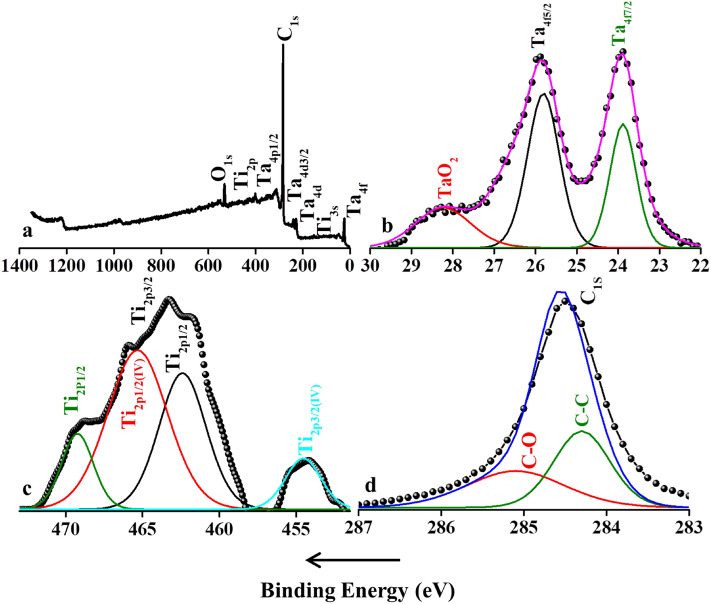

The vibrational modes ω4 and ω7 have undergone a complete shift to lower wavenumbers due to Al etching as the lattice parameter “c” suffers an increment of its value. Also, there are few unidentified active modes in the spectrum, which could be assigned to the interaction of Ti and Ta atoms in the MXene phase and out-of-plane vibrations70. Furthermore, XPS elemental analysis was carried out to investigate the oxidation state and chemical composition of the synthesized MXene sample, which is given in (Fig. 4). Distinct peaks due to the presence of elements of titanium (Ti), tantalum (Ta), aluminum (Al) and oxygen (O) were visible in the full scan survey. The binding energies of tantalum and other elements are in phase with the existing reports27,32,71. The full scan spectrum of TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene sheets in the Al region confirm that the synthesized materials were aluminum-free after HF etching processes (Fig. 4a). The spectrum of the Ta 4f. region was fitted by following 4f5/2 and 4f7/2 components that correspond to elemental Ta metals and its oxides as TaO2 (red) that are the two main species. The Ta 4f5/2 (black) and Ta 4f7/2 (green) binding energies are around 25.9 and 23.8 eV indicating that tantalum is in carbide environment (Fig. 4b). TaO2 has weak peaks probably that arise from the surface oxidation of the MXene sheets. The deconvoluted spectrum of Ti 2p spectra consists of four sets of doublet peaks corresponding to 2p3/2(IV) and 2p1/2(IV) of elemental metal and oxidized states of titanium (Fig. 4c). The dominant Ti 2p3/2 peaks at about 454.2 and 463.1 eV are assigned to the metallic Ti and Ti4+ states, respectively. In the de-convoluted spectrum of carbon, distant peaks at 284.6 eV, 283.3 eV and 283.7 eV are due to graphitic Sp2 carbon (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Full scan survey and deconvoluted XPS spectra of the synthesized bi-metal TixTa(4−x)C3 (a) full scan survey of the synthesized MXene (b) deconvoluted spectrum of Ti, (c) deconvoluted spectrum of Ta, (d) deconvoluted spectrum of C.

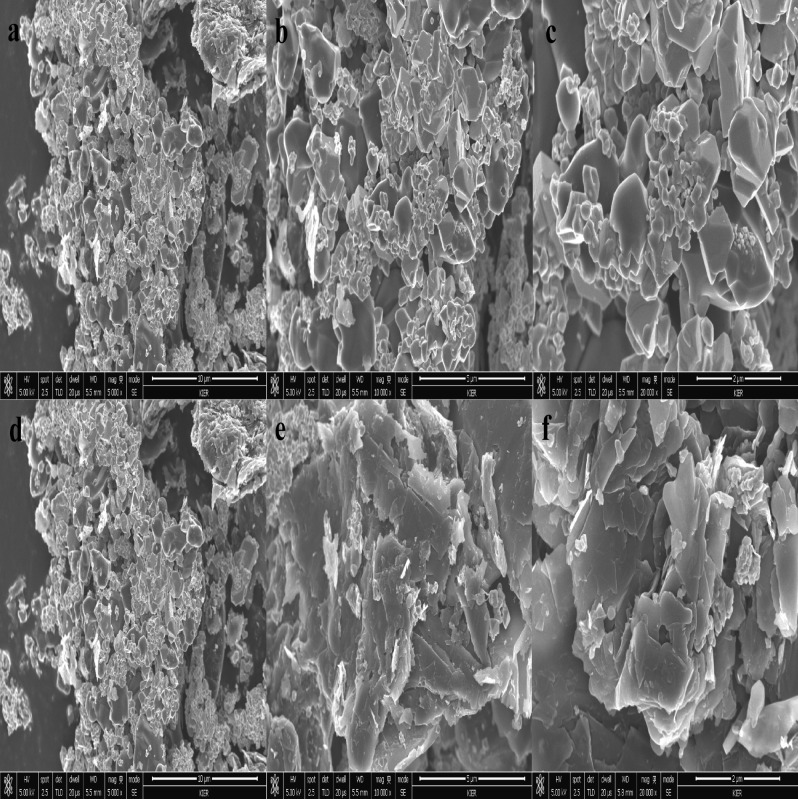

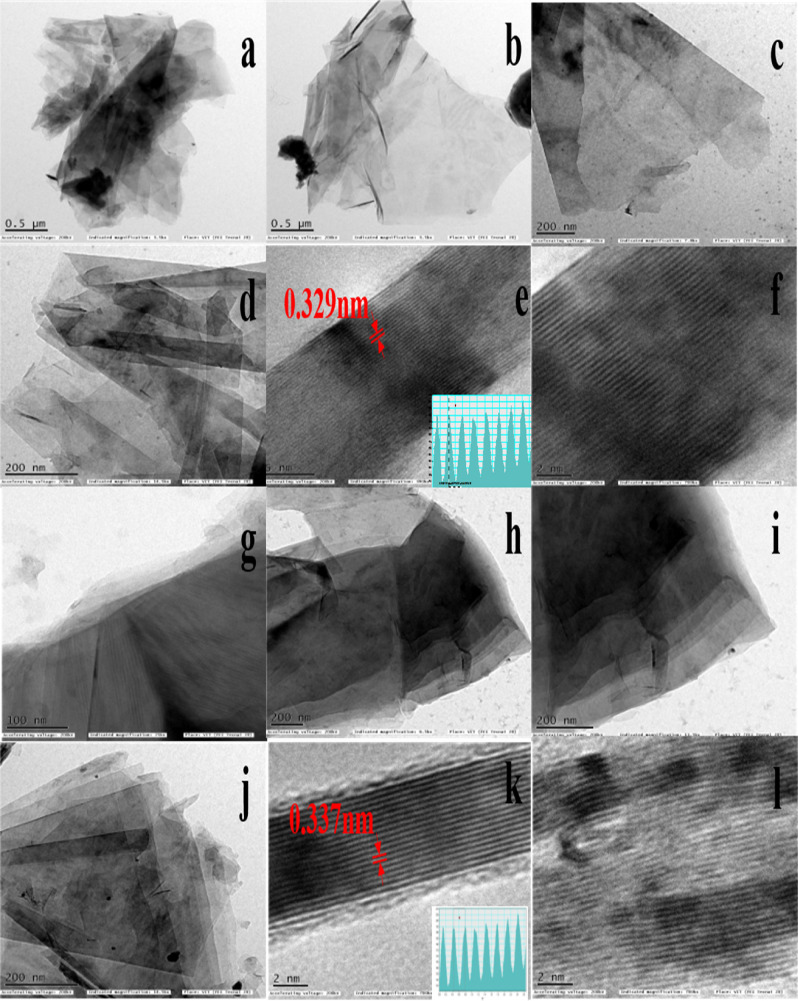

FE-SEM images of the synthesized bi-metal TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase and MXene samples are given in Fig. 5. The images show that the morphology of the synthesized MAX phase are in a layered solid structure (Fig. 5a–c). A small amount of nano layered structure was also observed, which can be attributed to the presence of other impurity phases in the sample. whereas the MXene sample shows that the layers are exfoliated during the etching processes (Fig. 5d–f). In case of both MAX phase and MXenes, at higher magnification of 10 µm both morphology looks similar. When the magnification is reduced to 5 µm and 2 µm, there is a clear difference in as the MAX phase with layered solid structure and etched MXene has an exfoliated layered structure with surface roughness because of etching processes. Furthermore, TEM micrographs of both the MAX phase and MXene are given in Fig. 6a–l, in which both the MAX phase and MXene exhibit layered structure and a thin arrangement enough to be electronically transparent; as the number of layers increases, this moved to a darker shade. Notably, the d-spacing of MXene increased from 0.329 nm to 0.337 nm at (004) plane due to the removal of Al atoms during the HF etching, which is in good agreement with that d-spacing calculated from the XRD data. As seen in (Fig. 6e,k), in comparision with the MAX phase, surface of the MXene sample is rough as a result of the surface functalization during thr etching processes. Understanding dislocations and kink bands were quite difficult until Morgiel et al. described them in their publication “Microstructure of Ti3SiC2 based ceramics in 1996”72. The dipole formed by the two dislocation segments is quite common in layered solids and other materials as MAX phases73 and mica74. It is evident from the FE-SEM and TEM images of both MAX phases and MXene that samples have a kink band (Fig. 5i). Since kinking is a type of buckling, porosity will enhance in the kinking effect75,76. The kink band favors electrochemical performance to a certain extent77,78. As seen in (Fig. 6f,i) in case of MAX phase, the HRTEM images were in darker shades because of thre layered solid behaviour, but it can be clearly distingushable in case of the MXene sample as there are different shades because of difference in thickness and spacing obtained due to removal of Al during the etchign processes.

Figure 5.

FE-SEM images of bi-metallic (a–c) TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase and (d–f) TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene at various magnifications.

Figure 6.

TEM micrographs of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase (a–f) and TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene (g–l).

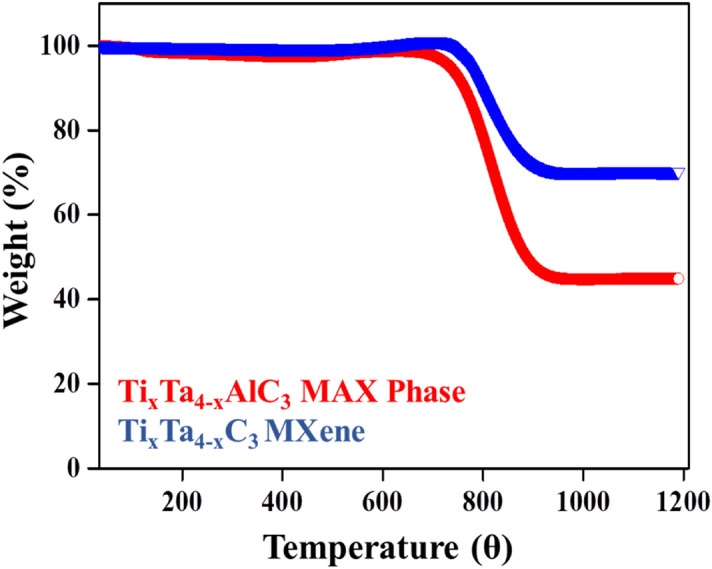

In order to understand the thermal behavior of the sample, thermogravimetric analysis was carried out from RT to 1200 °C. The analysis results are given in (Fig. 7), which shows a heavyweight loss for the MAX phase due to the loss of other impurities/mixed phases, whereas on the other hand in the case of MXene sample, the weight loss is less. In MAX phases, samples has the same behavior till 650 °C followed by huge weight loss from 650 to 900 °C, which might be because of TiO2 decomposition and/or due to formation of nanocrystals of TaC or TiC, which was also noticed in case of MXene sample and the weight loss patterns were in phase with the existing MXene literature67,79–83.

Figure 7.

TGA behavior of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase (Red) and TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene (blue).

The lamellar bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene was further evaluated using potentiostatic and galvanostatic methods to understand its electrochemical properties and redox mechanisms as Li-host anode material (Fig. S2) displays cyclic voltammograms recorded at scan rate of 0.2 mV s−1 from 0.01 to 3.0 V vs Li/Li+. During the initial cathodic cycle, irreversible broad peaks appear around 0.99 and 0.53 V vs Li/Li+54, which are related to the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer formation and Li-ion adsorption on the MXene pores53. The intercalation reaction between TixTa(4−x)C3 and Li-ions occurs around 0.5 V vs Li/Li+, which can be expressed as: TixTa(4−x)C3 + xLi+ + xe− → LixTixTa(4−x)C353–55. The subsequent CV profiles reveal a stable cathodic electrochemical process and suggest a two-step lithiation process as described in the previous literature39. During the anodic scans, a broad peak centered at 0.31 V vs Li/Li+ arises that is associated to Li-ion extraction process: LixTixTa(4−x)C3 → TixTa(4−x)C3 + xLi+ + xe−53–55. Also, the constant charge capacity beyond 0.5 V vs. Li/Li+ can be ascribed to the reversible redox Li-ion desorption processes on the active material surface or pores.

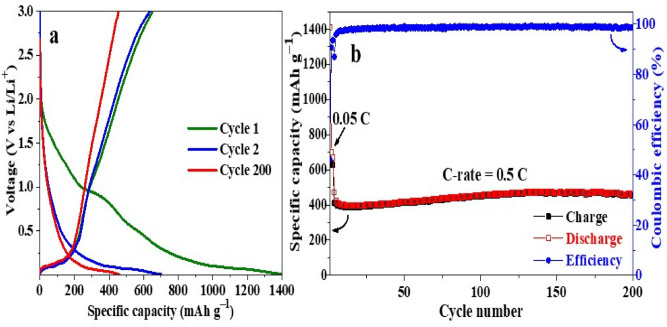

The cyclability and rate capability of the layered TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene were evaluated using galvanostatic (dis)charge measurements (Fig. 8a). The capacity delivered by the electrodes was estimated based on the mass of TixTa(4−x)C3 and the applied C-rate was 1.0 °C = 372 mA g−1. Figure 7a shows the charge–discharge profiles of the TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode for cycle 1st, 2nd and 200th recorded at a C-rate of 0.5 °C, between a voltage window from 0.01 to 3.0 V vs. Li/Li+. The TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode gave an irreversible initial specific discharge capacity of around 1411 mAh g−1 at 0.05 °C-rate during the activation process. This non-reversible high value of discharge capacity was caused by the formation of the SEI layer that occurs during the 1st discharge cycle and might also be due to the formation of double Li layers between MXene layers39.

Figure 8.

Electrochemical cycling performance of the MXene sample, TixTa(4−x)C3: (a) (dis)charge profiles at cycle 1st, 2nd and 200th, (b) cycle performance after 200 cycles at C-rate of 0.5 °C.

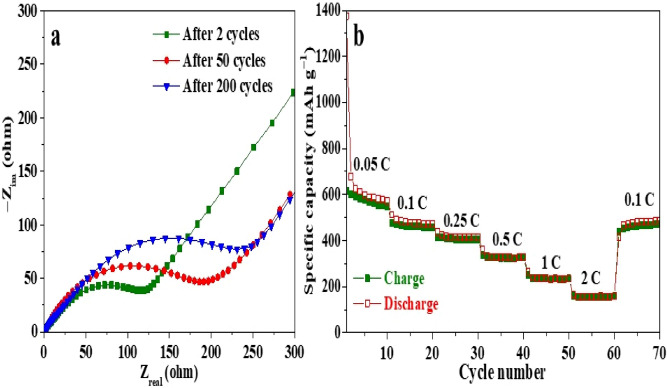

Remarkably, the MXene anode delivers a high specific discharge capacity of about 459 mAh g−1 at a C-rate 0.5 °C with a capacity retention of about 97% after the activation process (cycle 3) and a coulombic efficiency of around 99% after 200 cycles. Figure 8b displays the cycle performance of the layered TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode, which shows a stable cycling behavior with a slight increase of capacity during some cycles, reaching a discharge capacity of 476 mAh g−1 at a 0.5 °C-rate after 100 cycles, which decay until 459 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles. This loss of capacity could be associated with the disconnection of the active particles from the electrode as a result of the formation of a thick SEI between the MXene layers or might also be due to the restacking of the layered MXene material84, which can generate mechanical stress, cracks, and fractures inside the anodic electrode85. Figure 9a presents the Nyquist plot of fresh and cycled bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode, in which the charge transfer resistance of the cycled electrode increases during cycling, indicating the formation and growth of a thick SEI layer as the number of cycles increases.

Figure 9.

(a) EIS data before and after 200 cycles and (b) rate capability test.

The rate capability of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode was further evaluated under various C-rates during 10 D-C cycles per applied C-rate (Fig. 9b). The MXene anode exhibits an average of specific discharge capacities of 602, 482, 418, 332, 237, 156 mAh g−1 and back to 472 mAh g−1 at applied C-rate of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1 °C, and backward to 0.1 °C, respectively. The MXene anode displays a remarkably high C-rate capability recovering 98% of the delivered capacity of 482 mAh g−1 at C-rate of 0.1 °C after being cycled at various C-rate conditions. The extraordinary Li-ion storage of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode could be related to the formation of a stable bi-metallic MXene material, which stores Li-ions on the surface of its layers during the redox process. The bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene anode demonstrated good electronic connectivity between the active materials, carbon additive and binder, showing stable electrochemical performance, high capacity and good rate capability51. Results show that the synthesized MXene achieved an excellent electrochemical redox performance compared to the known MXenes (Table 1), which could be attributed to the formation of a stable, promising bi-metallic MXene material, which store Li-ions on the surface of its layers.

Table 1.

Comparison of the bi-metallic TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene performance with reported MXene anodes.

| No | Electrode material | Battery type | Electrolyte salt | Cell voltage/V vs Li+/Li | Capacity/mAh g−1 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sn/Ti3C2 | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 1.0–3.0 | 635 at 0.5 °C | 86 |

| 2 | TixTa(4−x)C3 | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.2–3.0 | 459 at 0.5 °C | This work |

| 3 | Nb2C/CNT | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 1.0–3.0 | 420 at 0.5 °C | 87 |

| 4 | Nb4C3 | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.01–3.0 | 380 at 1 °C | 88 |

| 5 | V2C | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.01–3.0 | 291 at 10 °C | 89 |

| 6 | V2C | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.02–3.0 | 254 at 0.2 °C | 90 |

| 7 | MoS2/Ti3C2 | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.01–3.0 | 246.1 at 10 °C | 91 |

| 8 | Ti3C2 | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.05–3.0 | 123.6 at 1 °C | 92 |

| 9 | Ti3C2Tx | Mg2+/Li+ | 0.4 M LiCl | 0.2–2.0 | 105 at 0.1 °C | 93 |

| 10 | LVO/Ti3C2Tx | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.01–3.0 | 71 at 5 °C | 94 |

| 11 | Ti2C | Li-ion | 1 M LiPF6 | 0.0–3.0 | 65 at 10 °C | 95 |

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first report, where bi-metallic titanium-tantalum carbide MXene TixTa(4−x)C3 was successfully prepared through a conventional etching process of TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase. XRD and Raman analysis proved that the MAX phase was successfully prepared via a consecutive ball milling and heat treatment route. The lamellar MXene structural arrangement remains after the HF etching process, which is Al free according to the XPS analysis. FE-SEM and TEM characterizations exposed the exfoliated nature of the TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene after removing the Al atoms from its corresponding MAX TixTa(4−x)AlC3 phase. It also revealed a delaminated MXene structure with an expanded interlayer d-spacing of 3.37 Å. The lamellar TixTa(4-x)C3 MXene was used as Li-ion host anode, giving a remarkably high reversible high specific discharge capacity of 459 mAh g−1 at of 0.5 °C rate with a coulombic efficiency of around 99% after 200 cycles and a capacity retention of about 97%. Also, the MXene anode presented a high rate capability, recovering 98% of the delivered capacity of 482 mAh g−1 at a C-rate of 0.1 °C after being cycled at various C-rate conditions. This new, electrochemically active TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene provides a new approach to design high-capacity and stable Li-host anode materials for the next generation of rechargeable batteries.

Experimental part

Titanium (Ti), tantalum (Ta), aluminum (Al), graphite (C) and hydrofluoric acid (HF) with high purity were acquired from Alfa Aesar, while toluene was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the chemicals were used without any further purification. Also, double distilled water was used to wash the resultant MXene material.

TiTa alloy preparation

The titanium-tantalum alloy (hereby referred to as TiTa) was synthesized by the powder metallurgy method using high purity Ti and Ta elements. During the alloy preparation stage, both elements were mixed with an atomic ratio of 1:1 through a ball milling process for 12 h at 250 rpm with a charge ratio of 1:10 under the presence of toluene. Then, the resultant sample was centrifuged and dried at 80 °C for 24 h, obtaining the TiTa alloy powder.

Synthesis of the MAX phase

To obtain TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase, the pre-alloyed TiTa powder, aluminum and graphite in the proper mass amount were ball milled for 10 h with a charge ratio of 10:1. Then, the resultant mixture was loaded on to a graphite punching die and hot pressed at 1500 °C during 3 h under 1 Ton of pressure and a vacuum of 2 × 10−5 mbar.

Synthesis of the MXene

To convert the synthesized TixTa(4−x)AlC3 MAX phase into TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene, 1 g of the raw material was immersed in 20 mL of 40 v/v% HF solution and stirred for 4 days. The resultant dispersion was washed with double distilled water, vacuum filtered and dried at 80 °C for 24 h, obtaining the TixTa(4−x)C3 MXene.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author K.M. Batoo extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number IFKSURG-1437-030. The authors thank to CONACYT-SENER for their financial support to Project No. 274314. Ravuri Syam sai thanks to the Vellore Institute of Technology—Vellore campus for the research fellowship. All the authors contributed equally to this work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Syed Farooq Adil which was incorrectly given as Syed Adil Farooq.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/14/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-92167-2

Contributor Information

Vilas G. Pol, Email: vpol@purdue.edu

Khalid Mujasam Batoo, Email: kbatoo@ksu.edu.sa.

Andrews Nirmala Grace, Email: anirmalagladys@gmail.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-79991-8.

References

- 1.Deng Y, Wan L, Xie Y, Qin X, Chen G. Recent advances in Mn-based oxides as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2014;4:23914–23935. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:4303–4417. doi: 10.1021/cr030203g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozawa K. Lithium-ion rechargeable batteries with LiCoO2 and carbon electrodes: the LiCoO2/C system. Solid State Ionics. 1994;69:212–221. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato, H., Yamamoto, Y., Nagamine, M. & Nishi, Y. Lithium ion rechargeable batteries. In Proc. WESCON ’93, Vol. 51, 210–214 (IEEE, 1993).

- 5.Brar VW, Koltonow AR, Huang J. New discoveries and opportunities from two-dimensional materials. ACS Photonics. 2017;4:407–411. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syamsai R, Rodriguez JR, Pol VG, Grace AN. Reversible, stable Li-ion storage in 2 D single crystal orthorhombic α-MoO3 anodes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;565:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mei J, Liao T, Kou L, Sun Z. Two-dimensional metal oxide nanomaterials for next-generation rechargeable batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1–25. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Z, et al. MoO2 @MoS2 nanoarchitectures for high-loading advanced lithium-ion battery anodes. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2017;34:1600223. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi W, et al. Recent development of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides and their applications. Mater. Today. 2017;20:116–130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naguib M, Mochalin VN, Barsoum MW, Gogotsi Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: A new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:992–1005. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anasori B, Lukatskaya MR, Gogotsi Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:16098. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang H, et al. MXene–2D layered electrode materials for energy storage. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2018;28:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winkless L. Knitting the future of supercapacitors. Mater. Today. 2020;35:1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitt A, et al. 3D knitted energy storage textiles using MXene-coated yarns. Mater. Today. 2020;34:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Shim J, Park JH, Lee S. MXene electrode for the integration of WSe2 and MoS2 field effect transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:5328–5334. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, He J, Nachtigall P, Grajciar L, Brivio F. Control of spintronic and electronic properties of bimetallic and vacancy-ordered vanadium carbide MXenes via surface functionalization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019;21:25802–25808. doi: 10.1039/c9cp05638f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zha XH, et al. The thermal and electrical properties of the promising semiconductor MXene Hf2CO2. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep27971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu J, et al. Recent advance in MXenes: A promising 2D material for catalysis, sensor and chemical adsorption. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;352:306–327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasool K, et al. Water treatment and environmental remediation applications of two-dimensional metal carbides (MXenes) Mater. Today. 2019;30:80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, et al. Vanadium carbide with periodic anionic vacancies for effective electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction. Mater. Today. 2020;40:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan H. Ultra-high electrochemical catalytic activity of MXenes. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32531. doi: 10.1038/srep32531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha A, et al. MXene: An emerging material for sensing and biosensing. Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;105:424–435. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H, et al. A novel nitrite biosensor based on the direct electrochemistry of hemoglobin immobilized on MXene-Ti3C2. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015;218:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rakhi RB, Nayuk P, Xia C, Alshareef HN. Novel amperometric glucose biosensor based on MXene nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep36422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhabeb M, et al. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene) Chem. Mater. 2017;29:7633–7644. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasool K, et al. Efficient antibacterial membrane based on two-dimensional Ti3C2Tx (MXene) nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01714-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Wang Y, Gao S, Chen Y, Shi J. Theranostic 2D tantalum carbide (MXene) Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1703284. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shuck CE, Gogotsi Y. Taking MXenes from the lab to commercial products. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;401:125786. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowotny H. Structural chemistry of refractory metallic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. English. 1970;9:173–174. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barsoum MW, El-Raghy T. Synthesis and characterization of a remarkable ceramic: Ti3SiC2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1996;79:1953–1956. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deysher G, et al. Synthesis of Mo4VAlC4 MAX Phase and Two-Dimensional Mo4VC4 MXene with Five Atomic Layers of Transition Metals. ACS Nano. 2020;14:204–217. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b07708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syamsai R, Grace AN. Ta4C3 MXene as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Alloys Compd. 2019;792:1230–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naguib M, et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:4248–4253. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naguib M, et al. Synthesis of a new nanocrystalline titanium aluminum fluoride phase by reaction of Ti 2AlC with hydrofluoric acid. RSC Adv. 2011;1:1493–1499. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, et al. Two-dimensional Nb-based M4C3 solid solutions (MXenes) J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016;99:660–666. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao Q, et al. Two-dimensional Mo1.33C MXene with divacancy ordering prepared from parent 3D laminate with in-plane chemical ordering. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maughan PA, et al. Porous silica-pillared MXenes with controllable interlayer distances for long-life Na-Ion batteries. Langmuir. 2020;36:4370–4382. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halim J, et al. Transparent conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide epitaxial thin films. Chem. Mater. 2014;26:2374–2381. doi: 10.1021/cm500641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anasori B, et al. Two-dimensional, ordered, double transition metals carbides (MXenes) ACS Nano. 2015;9:9507–9516. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mutlu I. Characterisation of localised corrosion behaviour of Ti-Ta-Mo alloy for the nuclear industry. Corros. Rev. 2017;35:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou YL, Niinomi M, Akahori T. Effects of Ta content on Young’s modulus and tensile properties of binary Ti-Ta alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2004;371:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou YL, Niinomi M. Ti-25Ta alloy with the best mechanical compatibility in Ti-Ta alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2009;29:1061–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou YL, Niinomi M. Microstructures and mechanical properties of Ti-50 mass% Ta alloy for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2008;466:535–542. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mashtalir O, et al. Intercalation and delamination of layered carbides and carbonitrides. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1716. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anasori B, et al. Control of electronic properties of 2D carbides (MXenes) by manipulating their transition metal layers. Nanoscale Horizons. 2016;1:227–234. doi: 10.1039/c5nh00125k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boota M, et al. Pseudocapacitive electrodes produced by oxidant-free polymerization of pyrrole between the layers of 2D titanium carbide (MXene) Adv. Mater. 2016;28:1517–1522. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sang X, et al. Atomic defects in monolayer titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx) MXene. ACS Nano. 2016;10:9193–9200. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Römer FM, et al. Controlling the conductivity of Ti3C2 MXenes by inductively coupled oxygen and hydrogen plasma treatment and humidity. RSC Adv. 2017;7:13097–13103. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu T, Yang J, Wang X. Carbon vacancies in Ti2CT2 MXenes: Defects or a new opportunity? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:31773–31780. doi: 10.1039/c7cp06593k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan TL, Jin HM, Sullivan MB, Anasori B, Gogotsi Y. High-throughput survey of ordering configurations in MXene alloys across compositions and temperatures. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4407–4418. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b08227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naguib M, et al. MXene: A promising transition metal carbide anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2012;16:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmed B, Anjum DH, Hedhili MN, Gogotsi Y, Alshareef HN. H2 O2 assisted room temperature oxidation of Ti2C MXene for Li-ion battery anodes. Nanoscale. 2016;8:7580–7587. doi: 10.1039/c6nr00002a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao MQ, et al. 2D titanium carbide and transition metal oxides hybrid electrodes for Li-ion storage. Nano Energy. 2016;30:603–613. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang J, et al. Sandwich-like Na0.23TiO2 nanobelt/Ti3C2 MXene composites from a scalable in situ transformation reaction for long-life high-rate lithium/sodium-ion batteries. Nano Energy. 2018;46:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed B, Anjum DH, Gogotsi Y, Alshareef HN. Atomic layer deposition of SnO2 on MXene for Li-ion battery anodes. Nano Energy. 2017;34:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian Y, An Y, Feng J. Flexible and freestanding silicon/MXene composite papers for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:10004–10011. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, et al. MXene/Si@SiOx@C layer-by-layer superstructure with autoadjustable function for superior stable lithium storage. ACS Nano. 2019;13:2167–2175. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xia M, et al. Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets as a robust and conductive tight on Si anodes significantly enhance electrochemical lithium storage performance. ACS Nano. 2020;14:5111–5120. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c01976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng R, et al. Black phosphorus quantum dot/Ti3C2 MXene nanosheet composites for efficient electrochemical lithium/sodium-ion storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez JR, et al. Ge2Sb2Se5 glass as high-capacity promising lithium-ion battery anode. Nano Energy. 2020;68:104326. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Syamsai R, Grace AN. Ta4C3 MXene as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Alloys Compd. 2019;792:1230–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin JO, et al. Microstructural characterization and properties of Ti-28Ta at.% powders produced by plasma rotating electrode process. J. Alloys Compd. 2017;713:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 63.He Y, et al. Fabrication of Ti-Al micro/nanometer-sized porous alloys through the kirkendall effect. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:2102–2106. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, et al. Synthesis of Ti-Ta alloys with dual structure by incomplete diffusion between elemental powders. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015;51:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Griseri M, et al. Synthesis, properties and thermal decomposition of the Ta4 AlC3 MAX phase. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019;39:2973–2981. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghidiu M, Barsoum MW. The 110 reflection in X-ray diffraction of MXene films: Misinterpretation and measurement via non-standard orientation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017;100:5395–5399. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Syamsai R, Kollu P, Kwan Jeong S, Nirmala Grace A. Synthesis and properties of 2D-titanium carbide MXene sheets towards electrochemical energy storage applications. Ceram. Int. 2017;43:13119–13126. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Presser V, et al. First-order Raman scattering of the MAX phases: Ti2AlN, Ti2AlC0.5N0.5, Ti2AlC, (Ti0.5V0.5)2AlC, V2AlC, Ti3AlC2, and Ti3GeC2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2012;43:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barsoum MW. The Mn+1AXn phases: A new class of solids. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2000;28:201–281. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarycheva A, Gogotsi Y. Raman spectroscopy analysis of structure and surface chemistry of Ti3C2TxMXene. Chem. Mater. 2020;32:3480–3488. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheppard LR, Holik J, Liu R, Macartney S, Wuhrer R. Tantalum enrichment in tantalum-doped titanium dioxide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014;97:3793–3799. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgiel J, Lis J, Pampuch R. Microstructure of Ti3 SiC2—Based ceramics. Mater. Lett. 1996;27:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tromas C, Villechaise P, Gauthier-Brunet V, Dubois S. Slip line analysis around nanoindentation imprints in Ti 3SnC2: A new insight into plasticity of MAX-phase materials. Philos. Mag. 2011;91:1265–1275. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meike A. In situ deformation of micas; a high-voltage electron-microscope study. Am. Miner. 1989;74:780–796. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barsoum MW, Farber L, El-Raghy T. Dislocations, kink bands, and room-temperature plasticity of Ti3SiC2. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 1999;30:1727–1738. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farber L, Barsoum MW, Zavaliangos A, El-Raghy T, Levin I. Dislocations and stacking faults in Ti3SiC2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005;81:1677–1681. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoshi N, Kawatani S, Kudo M, Hori Y. Significant enhancement of the electrochemical reduction of CO2 at the kink sites on Pt(S)-[n(110) × (100)] and Pt(S)-[n(100) × (110)] J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999;467:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Plieth W, Georgiev GS. Residence times in kink sites and Markov chain model of alloy and intermetallic compound deposition. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2006;42:1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu R, Li W. High-thermal-stability and high-thermal-conductivity Ti3C2T x MXene/poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) composites. ACS Omega. 2018;3:2609–2617. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b02001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Syamsai R, Grace AN. Synthesis, properties and performance evaluation of vanadium carbide MXene as supercapacitor electrodes. Ceram. Int. 2020;46:5323–5330. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seredych M, et al. High-temperature behavior and surface chemistry of carbide MXenes studied by thermal analysis. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:3324–3332. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma G, Naguib M, Feng D, Gogotsi Y, Navrotsky A. Calorimetric determination of thermodynamic stability of MAX and MXene phases. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:28131–28137. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou J, et al. A two-dimensional zirconium carbide by selective etching of Al3 C3 from Nanolaminated Zr3Al3C5. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:5008–5013. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Radin MD, Alvarado J, Meng YS, Van Der Ven A. Role of crystal symmetry in the reversibility of stacking-sequence changes in layered intercalation electrodes. Nano Lett. 2017;17:7789–7795. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu J, Deshpande RD, Pan J, Cheng Y-T, Battaglia VS. Electrode side reactions, capacity loss and mechanical degradation in lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015;162:A2026–A2035. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luo J, et al. Sn4+ ion decorated highly conductive Ti3C2 MXene: Promising lithium-ion anodes with enhanced volumetric capacity and cyclic performance. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2491–2499. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mashtalir O, Lukatskaya MR, Zhao MQ, Barsoum MW, Gogotsi Y. Amine-assisted delamination of Nb2C MXene for li-ion energy storage devices. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:3501–3506. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhao S, et al. Li-ion uptake and increase in interlayer spacing of Nb 4 C 3 MXene. Energy Storage Mater. 2017;8:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu F, et al. Preparation of high-purity V2C MXene and electrochemical properties as Li-Ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017;164:A709–A713. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou J, Gao S, Guo Z, Sun Z. Ti-enhanced exfoliation of V2AlC into V2C MXene for lithium-ion battery anodes. Ceram. Int. 2017;43:11450–11454. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shen C, et al. MoS2-decorated Ti3C2 MXene nanosheet as anode material in lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017;164:A2654–A2659. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun D, et al. Two-dimensional Ti3C2 as anode material for Li-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2014;47:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Byeon A, et al. Two-dimensional titanium carbide MXene as a cathode material for hybrid magnesium/lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:4296–4300. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b04198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang Y, et al. A safe and fast-charging lithium-ion battery anode using MXene supported Li3 VO4. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:11250–11256. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Come J, et al. A non-aqueous asymmetric cell with a Ti2C-based two-dimensional negative electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012;159:A1368–A1373. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.