Abstract

In this letter, we reanalyze published mass spectrometry datasets of clinical samples with a focus on determining the co-infection status of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. We demonstrate the use of ComPIL 2.0 software along with a metaproteomics workflow within the Galaxy platform to detect cohabitating potential pathogens in COVID-19 patients using mass spectrometry-based analysis. From a sample collected from gargling solutions, we detected Streptococcus pneumoniae (opportunistic and multidrug-resistant pathogen) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (a probiotic component) along with SARS-Cov-2. We could also detect Pseudomonas sps. Bc-h from COVID-19 positive samples and Acinetobacter ursingii and Pseudomonas monteilii from COVID-19 negative samples collected from oro- and nasopharyngeal samples. We believe that the early detection and characterization of co-infections by using metaproteomics from COVID-19 patients will potentially impact the diagnosis and treatment of patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Keywords: Mass Spectrometry, metaproteomics, microbial peptides, pandemic, co-infection, nosocomial, diagnosis, spectral validation, Galaxy platform and bioinformatics

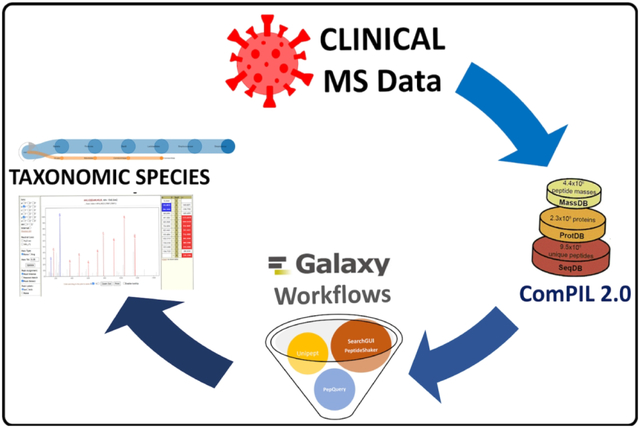

Graphical Abstract

In the current COVID-19 pandemic, sensitive and high-throughput diagnostic methods are essential for the identification of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. Rapid and accurate tests ensure that proactive measures can be taken to trace the sources and limit the spread of the infection. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can be detected from nasal swab, tracheal aspirate or blood, urine and stool specimens of infected patients by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which, along with other direct detection methods is considered the gold standard for an active infection1. On the other hand, indirect testing methods, such as sampling for specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, are used to infer previous exposure to the virus.

For direct detection, researchers have started exploring mass spectrometry (MS)-based assays to detect viral antigens from respiratory tract samples2–4. High resolution MS-based targeted assays coupled with immunoaffinity purification are being developed to improve the sensitivity and/or specificity of detection5–6. While most of these approaches detect the infection by targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteins associated with host response, we believe that the MS-based proteomic datasets can also be further utilized to identify an understudied, but potentially important, co-infection status of the infected individual. Bacterial co-infections during respiratory-related viral outbreaks have shown to significantly contribute to fatalities as demonstrated in both the 1918 and 2009 pandemics7–8. Moreover, recent research reports have also shown that many fatalities attributed to COVID-19 viral infections could be due to patients’ predisposition to co-infections9.

Diagnosing and managing co-infections can be complex, as it is possible that opportunistic co-infecting organisms are present in patients prior to viral infection or are acquired during hospitalization. For example, chronic bacterial infections associated with Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be a risk factor for patients with severe COVID-19 infection10. Additionally, some COVID-19 patients with severe presentation are subject to prolonged mechanical ventilation augmenting their chances of developing nosocomial infections. Furthermore, the use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections is especially high among COVID-19 patients under intensive care. The global overuse of antibiotics can lengthen the growing roster of antibiotic resistant pathogens and present problems in pairing infective organisms with appropriate antibiotics in an effective and timely fashion when using culture-based testing for co-infecting microbes. Early diagnosis of multi-organism co-infection is also necessary to avoid complications during hospitalization. Therefore, there is a need for a discovery-based analytical workflow for rapidly detecting co-infecting pathogens in COVID-19 patients, enabling subsequent characterization of antibiotic resistance and offering a roadmap for appropriate medical intervention.

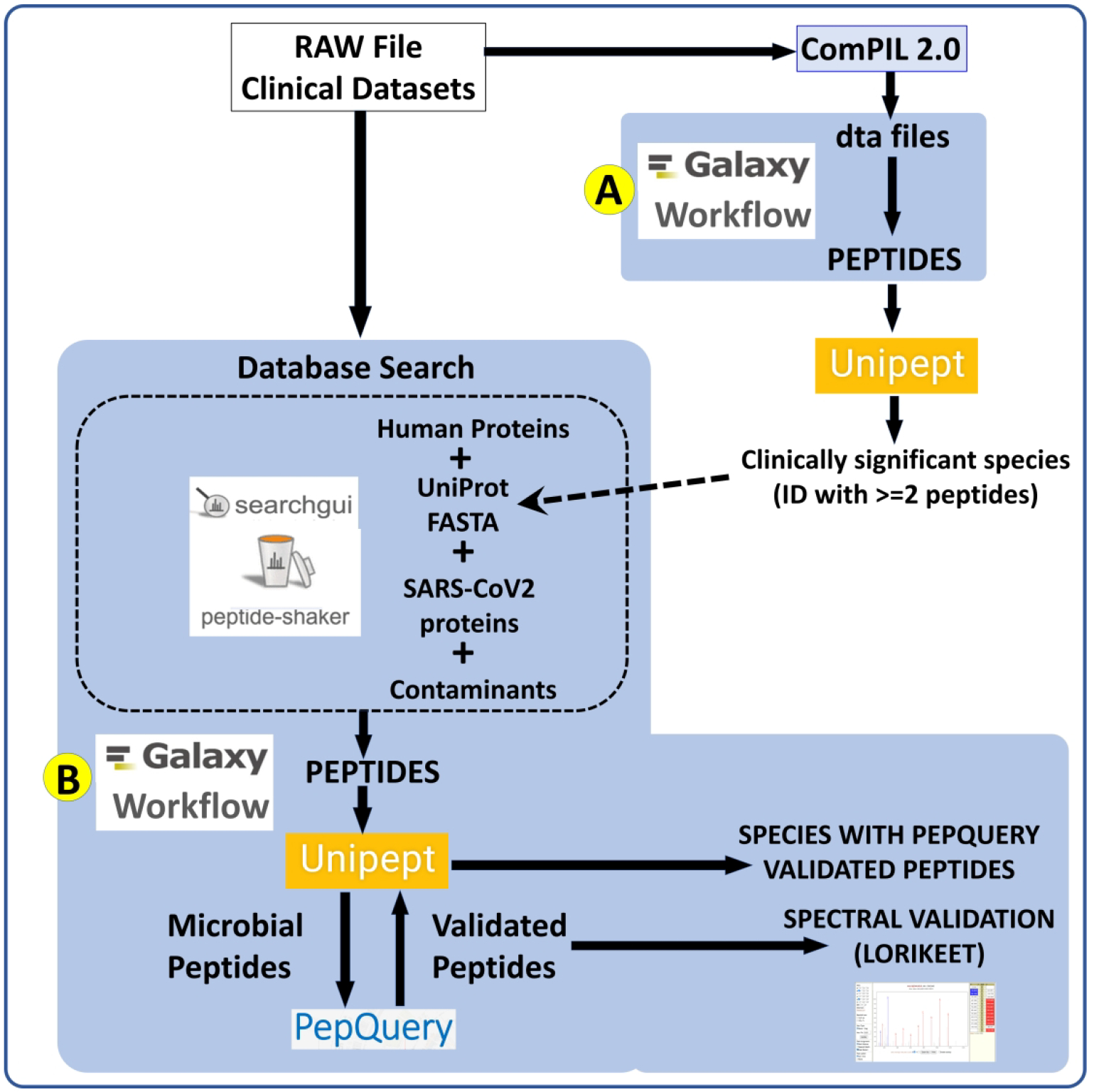

In this study, we present a metaproteomic bioinformatics workflow (Figure 1) that uses MS-based data from COVID-19 patients as an input to detect peptides associated with co-infecting organisms. MS files were searched using ComPIL 2.011 against a comprehensive protein sequence database and the detected peptides were used to find taxonomic information12 about microorganisms present in the sample. Based on the taxonomic information, the mass spectrometry data was re-interrogated using a metaproteomics workflow (Figure 1) within the Galaxy platform to: a) match tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) against a focused custom protein sequence database of clinically significant taxa; and b) verify detected peptides for their peptide-spectrum match (PSM) quality using the PepQuery software tool13 and the Lorikeet tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectral visualization tool14.

Figure 1. Metaproteomics workflows to detect co-habitating microorganisms from COVID-19 patient samples.

RAW Files from clinical datasets were searched against a comprehensive UniRef database using COMPIL 2.0 software. Peptides detected from COMPIL 2.0 search were extracted using a Galaxy workflow (A) that were subjected to Unipept analysis. Clinically important species (detected with at least two peptides) were used to generate the UniProt proteins FASTA database. The RAW files were re-interrogated against a combined database of human proteins, UniProt FASTA database of detected species, SARS-CoV-2 proteins and contaminants using SearchGUI/PeptideShaker within a Metaproteomics Search and Validation Workflow (B). Confidently identified peptides were subjected to Unipept analysis to detect microbial peptides and further confirmed by using PepQuery. The confirmed peptides were used to detect species (with at least 2 peptides) after validating the spectral quality of the microbial peptides by spectral validation (Lorikeet). Species were reported to be present in a sample only when they were detected by at least two peptides in a sample or replicate.

We demonstrate the use of ComPIL 2.0 and metaproteomics workflow to detect cohabitating, potential pathogens in COVID-19 patients using MS-based metaproteomics analysis from three published datasets2, 16, 18. We report the detection of microorganisms only when identified with at least two peptides per dataset (Table below). Each peptide detection was supported15 by confident identification by SearchGUI/PeptideShaker, confirmed by PepQuery analysis, and further validated by spectral annotation visualization via the Lorikeet viewer (Supplementary Data S1 and S2). From a sample collected from gargling solutions of COVID-19 positive patients2, we detected Streptococcus pneumoniae – an opportunistic pathogen that colonizes the mucosal surfaces of the human upper respiratory tract16 which has been detected in COVID-19 patient samples17 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus which is used in oral probiotic treatment18. We detected Pseudomonas sps. Bc-h peptides from COVID-19 positive samples, which is an unclassified strain that has not been previously shown to be associated with infection. We could detect only SARS-CoV-2 peptides from respiratory tract samples19. We could detect Pseudomonas monteilii and Acinetobacter ursingii from COVID-19 negative samples collected from oro- and nasopharyngeal samples20. Multi-drug resistant strains of Pseudomonas monteilii have been isolated in human bronchial aspirates of hospitalized patients21, 22. Acinetobacter ursingii, a commensal bacterium present in newborns, can also cause bacteraemic infections in premature infants23. A. ursingii has also been isolated from bronchoscopic samples of intensive-care patients24.

We believe that this untargeted metaproteomics approach offers an important step towards clinical co-infection diagnostics, wherein unbiased, direct detection of microbial peptides and inferred proteins can be performed without the requirement of accompanying metagenomic data from the patients or the use of co-culturing methods. Untargeted identification of microbial peptides, followed by rigorous determination of the most reliably detected sequences, as accomplished by our bioinformatics workflow, lays the groundwork for accurate proteotyping of clinical samples25 via targeted MS-based assays26. Moreover, the detection of co-infecting agents at the protein level can complement PCR-based methods while also offering direct evidence for an active growth of microbial agents during COVID-19 infection. We are hopeful that the workflow proposed in this study will potentially impact the diagnosis and treatment of patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data associated with this study along with bioinformatic workflows employed are accessible via a Zenodo link15, supplementary data (S1 and S2) and the COVID-19 Galaxy resource (https://covid19.galaxyproject.org/proteomics/).

| Dataset | Organisms detected in COVID-19 patient samples | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Gargling solution (PXD019423)2 | Streptococcus pneumoniae16–17, Lactobacillus rhamnosus18 and SARS-CoV-2 | https://covid19.galaxyproject.org/proteomics/mPXD019423/ |

| Oro- and Naso-pharyngeal tract (PXD020394)19 | Pseudomonas monteilii21–22, Pseudomonas sps. Bc-h, Acinetobacter ursingii23–24 and SARS-CoV-2 | https://covid19.galaxyproject.org/proteomics/mPXD020394/ |

| Respiratory tract (PXD021328)20 | SARS-CoV-2 | https://covid19.galaxyproject.org/proteomics/mpxd021328/ |

Supplementary Material

Funding Information:

We acknowledge funding for this work from the grant National Cancer Institute - Informatics Technology for Cancer Research (NCI-ITCR) grant 1U24CA199347 and National Science Foundation grant 1458524. The European Galaxy server that was used for data analysis is in part funded by Collaborative Research Centre 992 Medical Epigenetics (DFG grant SFB 992/1 2012) and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF grants 031 A538A/A538C RBC, 031L0101B/031L0101C de.NBI-epi, 031L0106 de.STAIR (de.NBI)).

References:

- 1.Russo A, Minichini C, Starace M, Astorri R, Calò F, Coppola N; Vanvitelli COVID-19 group. Current Status of Laboratory Diagnosis for COVID-19: A Narrative Review. Infect Drug Resist. 2020. Aug 3;13:2657–2665. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S264020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ihling C, Tänzler D, Hagemann S, Kehlen A, Hüttelmaier S, Arlt C, Sinz A. Mass Spectrometric Identification of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins from Gargle Solution Samples of COVID-19 Patients. J Proteome Res. 2020. Jun 23:acs.jproteome.0c00280. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00280. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zecha J, Lee CY, Bayer FP, Meng C, Grass V, Zerweck J, Schnatbaum K, Michler T, Pichlmair A, Ludwig C, Kuster B. Data, Reagents, Assays and Merits of Proteomics for SARS-CoV-2 Research and Testing. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2020. Sep;19(9):1503–1522. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA120.002164. Epub 2020 Jun 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whetton AD, Preston GW, Abubeker S, Geifman N. Proteomics and Informatics for Understanding Phases and Identifying Biomarkers in COVID-19 Disease. J Proteome Res. 2020. Jul 24:acs.jproteome.0c00326. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00326. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gouveia D, Miotello G, Gallais F, Gaillard JC, Debroas S, Bellanger L, Lavigne JP, Sotto A, Grenga L, Pible O, Armengaud J. Proteotyping SARS-CoV-2 Virus from Nasopharyngeal Swabs: A Proof-of-Concept Focused on a 3 Min Mass Spectrometry Window. J Proteome Res. 2020. Aug 5. doi:. 10.21/acs.jproteome.0c00535. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renuse S, Vanderboom PM, Maus AD, Kemp JV, Gurtner KM, Madugundu AK, Chavan S, Peterson JA, Madden BJ, Mangalaparthi KK, Mun D, Singh S, Kipp BR, Dasari S, Singh RJ, Grebe SK, Pandey A Development of mass spectrometry-based targeted assay for direct detection of novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus from clinical specimens medRxiv https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.05.20168948v1 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.05.20168948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008. Oct 1;198(7):962–70. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA, Barnes M, Ridda I, Seale H, Toms R, Heywood A. The role of pneumonia and secondary bacterial infection in fatal and serious outcomes of pandemic influenza a(H1N1)pdm09. BMC Infect Dis. 2018. Dec 7;18(1):637. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3548-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu X, Ge Y, Wu T, Zhao K, Chen Y, Wu B, Zhu F, Zhu B, Cui L. Co-infection with respiratory pathogens among COVID-2019 cases. Virus Res. 2020. Aug;285:198005. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198005. Epub 2020 May 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020. Aug 13;56(2):2002108. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SKR, Jung T, Thuy-Boun PS, Wang AY, Yates JR 3rd, Wolan DW. ComPIL 2.0: An Updated Comprehensive Metaproteomics Database. J Proteome Res. 2019. Feb 1;18(2):616–622. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00722. Epub 2019 Jan 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurdeep Singh R, Tanca A, Palomba A, Van der Jeugt F, Verschaffelt P, Uzzau S, Martens L, Dawyndt P, Mesuere B. Unipept 4.0: Functional Analysis of Metaproteome Data. J Proteome Res. 2019. Feb 1; 18(2):606–615. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00716. Epub 2018 Dec 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen B, Wang X, Zhang B. PepQuery enables fast, accurate, and convenient proteomic validation of novel genomic alterations. Genome Res. 2019. Mar;29(3):485–493. doi: 10.1101/gr.235028.118. Epub 2019 Jan 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. https://uwpr.github.io/Lorikeet/

- 15.

- 16.Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018. Jun;16(6):355–367. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Ge Y, Wu T, Zhao K, Chen Y, Wu B, Zhu F, Zhu B, Cui L. Co-infection with respiratory pathogens among COVID-2019 cases. Virus Res. 2020. Aug;285:198005. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198005. Epub 2020 May 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meurman JH, Stamatova I. Probiotics: contributions to oral health. Oral Dis. 2007. Sep;13(5):443–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardozo KHM, Lebkuchen A, Okai GG, Schuch RA, Viana LG, Olive AN, Lazari CDS, Fraga AM, Granato CFH, Pintão MCT, Carvalho VM, Establishing a mass spectrometry-based system for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 in large clinical sample cohorts. Nat Commun, 11(1):6201(2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera B, Leyva A, Portela MM, Moratorio G, Moreno P, Durán R, Lima A. Quantitative proteomic dataset from oro- and naso-pharyngeal swabs used for COVID-19 diagnosis: Detection of viral proteins and host’s biological processes altered by the infection. Data Brief. 2020. Oct;32:106121. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106121. Epub 2020 Aug 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aditi, Shariff M, Beri K. Exacerbation of bronchiectasis by Pseudomonas monteilii: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2017. Jul 24;17(1):511. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elomari M, Coroler L, Verhille S, Izard D, Leclerc H. Pseudomonas monteilii sp. nov., isolated from clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997. Jul;47(3):846–52. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yakut N, Kepenekli EK, Karaaslan A, Atici S, Akkoc G, Demir SO, Soysal A, Bakir M. Bacteremia due to Acinetobacter ursingii in infants: Reports of two cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2016. Apr 15;23:193. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.193.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrego A, Pajares V, Fernández-Arias C, Vera P, Mancebo J. Bronchoscopy in Patients with COVID-19 with Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: A Single-Center Experience. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. Jul 15;202(2):284–287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-0945LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grenga L, Pible O, and Armengaud J, Pathogen proteotyping: A rapidly developing application of mass spectrometry to address clinical concerns, Clinical Mass Spectrometry, 2019; 14 Part A, Pages 9–17, ISSN 2376–9998, 10.1016/j.clinms.2019.04.004. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2376999818300503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer JG, Schilling B. Clinical applications of quantitative proteomics using targeted and untargeted data-independent acquisition techniques. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017. May;14(5):419–429. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2017.1322904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.