Abstract

Social presence, or the feeling of being there with a “real” person, is a crucial component of interactions that take place in virtual reality. This paper reviews the concept, antecedents, and implications of social presence, with a focus on the literature regarding the predictors of social presence. The article begins by exploring the concept of social presence, distinguishing it from two other dimensions of presence—telepresence and self-presence. After establishing the definition of social presence, the article offers a systematic review of 233 separate findings identified from 152 studies that investigate the factors (i.e., immersive qualities, contextual differences, and individual psychological traits) that predict social presence. Finally, the paper discusses the implications of heightened social presence and when it does and does not enhance one's experience in a virtual environment.

Keywords: social presence, presence, virtual reality, virtual environments, immersion, computer-mediated communication

Introduction

Since its conceptualization, virtual reality (VR) has been touted as a novel communication medium that would radically change the way people interact with each other (Biocca and Levy, 2013). William Gibson famously described cyberspace as a “consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation” (Gibson, 1984, p. 51), portraying the social nature of “stepping through a barrier” (Slater and Wilbur, 1997, p. 2) into the virtual environment. More recently, VR pioneer Jaron Lanier, expressed his hope that VR would lead to new and exciting forms of communication (Lanier, 2017).

Despite the conceptualization of VR as a social medium wherein individuals could co-exist and interact with each other (Biocca and Levy, 2013), much of the early research on VR technology focused on single-user head-mounted display (HMD) systems that typically were not available outside of the laboratory. In more recent years, however, VR technology has rapidly made its transition from lab to home in various forms. This increased accessibility of VR technology has fueled a renewed interest in the social applications of VR, which is exemplified by the launch of multiple platforms including AltSpace VR, Facebook Spaces, High Fidelity, Normal VR, Oculus Medium, Rec Room, Sansar, and VR Chat.

One of the primary attractions of VR is purported to be the level of social presence it affords in comparison to other forms of technology-mediated communication. Social presence refers to the subjective experience of being present with a “real” person and having access to his or her thoughts and emotions (Biocca, 1997); as such, one of the primary goals of networked communication systems is to offer higher levels of social presence (Biocca and Harms, 2002). Earlier forms of text-based computer-mediated communication (CMC) offered a limited amount of verbal and nonverbal information, which subsequently reduced the level of social presence people could feel within a set amount of time. Recent advancements in technology, however, have made media far more immersive than the past; in contrast to earlier forms of CMC, wherein individuals could only use text-based cues to express themselves, VR systems have the capacity to offer a wide array of social cues through visual, audio, haptic, and—to a lesser extent—olfactory information. It is therefore necessary to understand how different technological features influence perceptions of social presence to inform the design of VR platforms.

Researchers have also found that social presence can be influenced by contextual and individual factors that impact perceptions of the psychological distance between interactants (e.g., Siriaraya and Ang, 2012; Kang and Gratch, 2014; Verhagen et al., 2014). Studies conducted by these researchers show that the communication context as well as the individual traits of the interactants can influence perceptions of social presence. One of the most significant contributions of this line of research is that it sheds light on when increasing immersion is (and is not) necessary in order to induce stronger feelings of social presence. In a similar vein, these studies can inform both academic and applied researchers on how to maximize the amount of social presence one can feel within a given virtual environment.

To understand the concept, antecedents, and implications of social presence, we will first define two key concepts of the current paper, namely immersion and presence. Then we will offer a brief description of two separate dimensions of presence—telepresence and self-presence—to distinguish them from social presence. The remainder of the paper will focus on synthesizing the research on the antecedents of social presence to explore what does (and does not) impact perceptions of social presence.

Immersion and the dimensions of presence

While some researchers use the terms “immersion” and “presence” interchangeably, distinguishing the two concepts allows for a better understanding of the difference between the technological qualities and psychological experiences afforded by mediated communication. Immersion can be defined as a medium's technological capacity to generate realistic experiences that can remove people from their physical reality (Slater and Wilbur, 1997). When defined in this way, immersion can be objectively measured by the technological affordances of a medium. Media are more immersive when they can deliver “an inclusive, extensive, surrounding and vivid illusion of reality to the senses of a human participant” (Slater and Wilbur, 1997, p. 604). Features such as audio and visual quality, frame rate, stereoscopy, and field of view can impact the extent to which a system is immersive (Welch et al., 1996; Johnson and Stewart, 1999; Skalski and Whitbred, 2010; Cummings and Bailenson, 2016).

In contrast to immersion, presence is the subjective experience of actually being in the mediated virtual environment (Slater and Wilbur, 1997; Witmer and Singer, 1998; Walther and Parks, 2002). As presence is needed for people to fully experience a virtual environment, it has been the focus of both applied and academic work on virtual reality (Cummings et al., 2012). Presence can be further divided into three distinct subcategories: telepresence (spatial presence), self-presence, and social presence (Lee, 2004).

Telepresence can be defined as “the extent to which one feels present in the mediated environment, rather than in the immediate physical environment” (Steuer, 1992, p. 75). This dimension of presence relates strongly to how vividly the user experiences the environmental and spatial properties of the mediated environment. When the perception of telepresence is strong, people should no longer be aware that their experiences are being mediated through technology (Lombard and Ditton, 1997).

In contrast to telepresence, self-presence is the extent to which the “virtual self is experienced as the actual self” (Aymerich-Franch et al., 2012, p. 1). This dimension of presence differs from telepresence, as it is not related to how vividly one experiences his or her surroundings, but rather, how connected one feels to his or her virtual body, emotions, or identity (Ratan and Hasler, 2009).

Finally, social presence or co-presence, refers to the “sense of being with another” (Biocca et al., 2003, p. 456) and is dependent on the ease with which one perceives to have “the access to the intelligence, intentions, and sensory impressions of another” (Biocca, 1997, p. 22). The concept was first introduced as a theoretical framework to understand the interactions that took place on different forms of media (Short et al., 1976). Social presence differs from both telepresence and self-presence, as it requires a co-present entity that appears to be sentient. Social presence is an integral part of virtual environments that mediate people; without social presence, the mediated other is merely experienced as an artificial entity and not a social being (Lee et al., 2006a).

The evolution of social presence

Social presence was first conceptualized by Short et al. (1976) and was defined as the salience of the interactants and their interpersonal relationship during a mediated conversation. According to Short et al. (1976), intimacy and immediacy are the two core components of social presence. These two concepts are closely related to each other; intimacy refers to the feeling of connectedness that communicators feel during an interaction, while immediacy is the psychological distance between the communicators. Both intimacy and immediacy are determined by verbal and nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, vocal cues, gestures, and physical appearance (Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997). Short and colleagues argued that some media were more capable at delivering these cues, while others were not, emphasizing that social presence was a “quality of the medium itself” (Short et al., 1976, p. 65).

The view that social presence is technologically determined was also echoed by early CMC researchers who endorsed the cues-filtered-out perspective (see Walther and Parks, 2002 for review). For example, media richness theory (Daft and Lengel, 1986) claimed that different media varied in their ability to reproduce “rich” social information (e.g., immediate feedback, language variety, personalization, number of cues), thereby making some media more appropriate than others for certain tasks. Put otherwise, certain media are inherently superior to others in achieving a specific communication goal. While some researchers have since rejected this technology-driven conceptualization of social presence (e.g., Walther, 1992), others continue to examine whether people feel different levels of social presence when interacting via a specific medium compared to another. Studies that focus on how the modality or specific technological affordances of a medium (e.g., immersive features) impact social presence are based on the assumption that certain affordances of a medium can increase or decrease social presence when all other circumstances are equal (e.g., Axelsson et al., 2001; Moreno and Mayer, 2004; Zhan and Mei, 2013).

In contrast to these medium-centric views of social presence, Walther (1992) argued that individuals are capable of adapting to different communication media, and can thus achieve their communication goals accordingly. From this perspective, the experience of social presence is highly contingent on the interactants, rather than the medium itself. This view is known as social information processing theory (SIPT). According to this theory, communication environments that offer fewer verbal and/or nonverbal cues (e.g., text-based CMC) can produce equal levels of intimacy as face-to-face (FtF) communication, although it may take more time. Walther (1996) later expanded this theory to posit that people who communicate via text-based CMC platforms could, in some cases, achieve even higher levels of social presence than FtF interactants by carefully selecting which facets of themselves they wish to reveal (i.e., hyperpersonal model of communication). Subsequent studies have since shown that individuals adopt different strategies to convey socioemotional cues on platforms with relatively limited verbal and nonverbal cues (e.g., Ramirez et al., 2002; Antheunis et al., 2010).

While both SIPT and the hyperpersonal model posit that technology does not solely determine the level of social presence a medium can afford, it is important to note that neither perspective denies the inherent differences between media. When individuals are only given limited communication options (e.g., short timespan, specific task type, etc.), it is probable that the technological features of the environment will influence the level of social presence a person feels. At the same time, however, this perspective offers a more nuanced view of social presence; while the immersive qualities (i.e., computer system's technological capacity to deliver a vivid experience) can impact social presence, individual communication strategies as well as contextual differences have a significant effect on social presence.

Why does social presence matter?

While both telepresence and self-presence have received academic focus, social presence has been considered to be particularly important within virtual environments with social actors (regardless of whether they are controlled by actual people or computer algorithms). This is due to the impact of social presence on social influence. Studies have shown that social presence is associated with a variety of positive communication outcomes, such as persuasion and attraction (e.g., Fogg and Tseng, 1999; Lee et al., 2006a). For example, Hassanein and Head (2007) found that social presence was positively associated with trust, enjoyment, and perceived usefulness of an online shopping website, which led to greater purchase intentions. Another study wherein social presence was operationalized to focus on the extent to which participants felt like they were together with their partner similarly found that social presence predicted attraction toward a physically embodied agent (i.e., robot; Lee et al., 2006a).

Antecedents of social presence

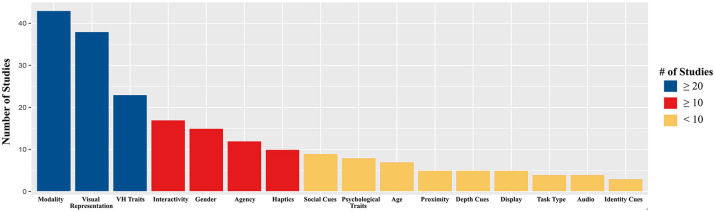

Because social presence often predicts positive communication outcomes, both academic researchers and practitioners have displayed a great interest in studying the factors that increase social presence. By reviewing 233 separate findings identified from 152 studies, we found that researchers have most often explored the influence of immersive qualities, contextual differences, and individual psychological traits on social presence (see Table 1). However, to the best of our knowledge, little effort has been made to synthesize the findings of these studies (for an exception, see Cummings and Wertz, 2018). Consequently, it is difficult to have a holistic understanding of which features are the most influential in predicting social presence. This paper attempts to overcome this shortcoming by offering a systematic review of the extant literature on the immersive, contextual, and psychological features that impact perceived social presence. The results, details, and general information of the studies that were reviewed are available in Tables 1–3.

Table 1.

Summary of study results.

| Predictor | References | Details | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMMERSION | ||||

| Modality | Appel et al., 2012 | Text vs. Avatar | + | |

| Alge et al., 2003 | CMC vs. FtF | + | ||

| Alghamdi et al., 2016 (Study 2) | Desktop vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Axelsson et al., 2001 | Desktop vs. CAVE | Null | ||

| Bailenson et al., 2006 | Audio vs. Audio+Video vs. Audio+Emotibox | Others > Audio+Emotibox | ||

| Bente et al., 2008 | Text vs. Audio vs. Audio+Video vs. Audio+Avatar | Others > Text | ||

| Cortese and Seo, 2012 | CMC vs. FTF | + | ||

| de Greef, 2014 | Audio vs. Audio+Video | +* | *Moderated by gender | |

| de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001 | Audio vs. Audio+Video | + | ||

| Francescato et al., 2006 | CMC vs. FtF | Null | ||

| Gimpel et al., 2016 | Text vs. Audio vs. Audio+Video | + | ||

| Hauber et al., 2005 | 2D vs. 3D vs. FtF | Others < FtF | ||

| Hauber et al., 2006 | 2D vs. 3D-local vs. 3D-remote vs. FtF | Others < FtF | ||

| Hauber et al., 2012 | Video vs. Video-CVE vs. Stereo large-screen video-CVE vs. FTF | Others < FtF* | *Moderated by gender | |

| Heldal et al., 2005 | IPT*-IPT vs. IPT-HMD vs. IPT-Desktop vs. Desktop-Desktop | IPT-IPT/HMD >Desktop-Desktop/IPT | *IPT: Immersive Projection Technology | |

| Hills, 2005 (Study 1) | 2D vs. 3D vs. FtF | + | ||

| Hills, 2005 (Study 2) | 2D vs. 3D | + | ||

| Homer et al., 2008 | Audio vs. Audio+Video | Null | ||

| Järvelä et al., 2016 | Nonverbal vs. Verbal | +* | *Moderated by physical proximity | |

| Jin, 2009 | Text vs. Audio | –* | *Moderated by product involvement | |

| Johnsen and Lok, 2008 | Large screen display vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Jung et al., 2017 | Picture vs. Video | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2014 | Text vs. Text+Video | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2013b | Text vs. Audio | + | ||

| Kothgassner et al., 2014 | HMD vs. FtF | + | ||

| Lee, 2013 | Television vs. Twitter | –* | *Moderated by Need-for-Cognition | |

| Lee and Jang, 2013 (Study 1) | Newspaper vs. Twitter | +* | *Moderated by affiliative tendency | |

| Lee and Jang, 2013 (Study 2) | Newspaper vs. Twitter | +* | *Moderated by affiliative tendency | |

| Lee and Shin, 2014 | Newspaper vs. Twitter | +* | *Moderated by transportability | |

| Moreno and Mayer, 2004 | Desktop vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Nam et al., 2008 | Visual+Haptic vs. Visual+Haptic+Audio | + | ||

| Nowak et al., 2009 | Text vs. Video | + | ||

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2005 | Text vs. Audio vs. Text+Audio | Null | ||

| Schroeder et al., 2001 | IPT-Desktop vs. IPT-IPT | IPT-Desktop < IPT-IPT | ||

| Sallnäs, 2005 (Study 1) | Text vs. Audio vs. Audio+Video | Others > Text | ||

| Sallnäs, 2005 (Study 2) | Audio vs. Audio+Video | Null | ||

| Sallnäs, 2005 (Study 2) | Web vs. CVE | Null | ||

| Slater et al., 1999 | Desktop vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Slater et al., 2000 | Desktop vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Steed et al., 1999 | Desktop vs. HMD | Null | ||

| Wideström et al., 2000 | Desktop vs. CAVE | Null | ||

| Yoo and Alavi, 2001 | Audio vs. Audio+Video | + | ||

| Zhan and Mei, 2013 | CMC vs. FtF | + | ||

| Visual representation | Bailenson et al., 2001 | Photographic realism | Null | |

| Bailenson et al., 2001 | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | + | ||

| Bailenson et al., 2003 (Study 1) | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | + | ||

| Bailenson et al., 2003 (Study 2) | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | + | ||

| Bailenson et al., 2005 | Match between visual and behavioral realism | + | ||

| Bente et al., 2007 (Study 1) | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | + | ||

| Bente et al., 2007 (Study 2) | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | Inverted U* | *Moderated by gender | |

| Bente et al., 2008 | Photographic realism (Low vs. High fidelity avatar) | Null | ||

| Casanueva and Blake, 2001 (Study 2) | Behavioral realism (Static vs. Dynamic) | + | ||

| Choi et al., 2001 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Clayes and Anderson, 2007 | Photographic realism (Avatar icon vs. Video image) | Null | ||

| Croes et al., 2016 | Invisible vs. Visible | + | ||

| Dalzel-Job, 2014 (Study 2) | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | Null | ||

| Fortin and Dholakia, 2005 | Vividness | + | ||

| Garau et al., 2003 | Match between visual and behavioral realism | + | ||

| Garau et al., 2005 | Behavioral realism (static vs. moving vs. responsive vs. talking) | Static < responsive | No other significant differences | |

| Gong, 2008 | Anthropomorphism (low vs. medium vs. high vs. real human) | + | ||

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 1) | Behavioral realism | + | ||

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 2) | Behavioral realism | + | ||

| Kang and Gratch, 2014 | Behavioral realism (High, Low, None) | Null | ||

| Kang and Watt, 2013 | Anthropomorphism (Low vs. High) | + | ||

| Kang and Watt, 2013 | Behavioral realism (Static vs. Dynamic) | Null | ||

| Kang et al., 2008 | Behavioral realism (Static vs. Dynamic) | + | ||

| Kang et al., 2008 | Visual realism (Graphic vs. Video) | + | ||

| Kim and Sundar, 2012 | Absent vs. Present (virtual character) | −* | *Moderated by interactivity | |

| Kim et al., 2004 | Pointer (Absent vs. Present) | − | ||

| Kim et al., 2013b | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2005 | Behavioral realism (Low vs. High developmental capacity) | + | ||

| Meyer and Lohner, 2012 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Anthropomorphism (No image vs. Low vs. High) | No image/High < Low | ||

| Pan et al., 2008 | Blushing behavior (non vs. cheeks vs. whole face) | Others < Whole Face | ||

| Park and Sundar, 2015 | Absent vs. Picture vs. Emoticon | Absent/Picture < Emoticon | ||

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2005 | 3D Avatar (Absent vs. Present) | Null | ||

| Shahid et al., 2012 | Behavioral realism (Mutual gaze) | + | ||

| Vishwanath, 2016 (Study 2) | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| von der Pütten et al., 2010 | Behavioral realism | + | ||

| Wu et al., 2014 | Behavioral realism (Static vs. Dynamic) | + | ||

| Xu, 2014 | Absent vs. Present (profile picture) | + | ||

| Interactivity | Fortin and Dholakia, 2005 | Low vs. Medium vs. High interactivity | +* | *Moderated by Need-for-Cognition |

| Garau et al., 2005 | Responsiveness | + | ||

| Han et al., 2016 | Machine & person interactivity | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2007 | Not interactive (offline quiz) vs. Interactive (online quiz) | + | ||

| Lee and Shin, 2012 | Low vs. High interactivity | +* | *Moderated by affiliative tendency | |

| Lim and Lee-Won, 2017 | Monologic vs. Dialogic | + | ||

| Nowak et al., 2009 | Synchronocicity (Low vs. High) | + | ||

| Park and Sundar, 2015 | Synchronocicity (Low vs. Medium vs. High) | Low/Medium < High | ||

| Phillips and Lee, 2005 (Study 3) | None vs. Simple vs. Complex | None/Simple < Complex | ||

| Qin et al., 2013 | Synchronocicity (Haptic packet data loss: 0.3 vs. 0.2 vs. 0.1 vs. none) | + | ||

| Rauh and Renfro, 2004 | Synchronocicity (No feedback delay vs. Feedback delay) | Null | ||

| Rauwers et al., 2016 | Internal communication features: Absent vs. Present | + | Null for external communication features | |

| Shimoda, 2007 | Generic vs. Tailored vs. Feedback-driven message | Null | ||

| Skalski and Tamborini, 2007 | Not interactive vs. Interactive | + | ||

| Zelenkauskaite and Bucy, 2009 | Passive vs. Interactive | + | ||

| Haptic feedback | Basdogan et al., 2000 | Absent vs. present | + | |

| Chellali et al., 2011 | Absent vs. present | + | ||

| Giannopoulos et al., 2008 | Absent vs. present | + | ||

| Jordan et al., 2002 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2004 | Absent vs. present | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2017 | Sound vs. Sound + Vibrotactile Feedback | + | No differences found between No Sound vs. Sound/Sound+Vibrotactile Feedback | |

| Lee et al., 2018 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Nam et al., 2008 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Sallnäs, 2010 | Absent vs. Present | + | ||

| Sallnäs et al., 2000 | Absent vs. present | Null | ||

| Depth cues | Ahn et al., 2014 | Stereoscopy (Mono vs. Stereo) | + | |

| Kim et al., 2012 (Study 1) | Mono vs. Motion parallax vs. Stereo+Motion parallax | Mono < Motion parallax/Stereo+Motion parallax | ||

| Kim et al., 2012 (Study 2) | Mono vs. Motion parallax vs. Stereo+Motion parallax | Mono < Motion parallax/Stereo+Motion parallax | ||

| Mühlbach et al., 1995 (Study 1) | Stereoscopy (Mono vs. Stereo) | + | ||

| Takatalo et al., 2011 | Mono vs. Medium stereo separation vs. High stereo separation | Inverted U | ||

| Audio quality | Christie, 1974 | Singlespeaker (speakerphone/high-fidelity speaker phone) vs. Multi-speaker | + | |

| Dicke et al., 2010 | Monophonic vs. Stereophonic vs. Binaural | Binaural > Mono/Stereo | ||

| Skalski and Whitbred, 2010 | Two-Channel Sound vs. Surround Sound | + | ||

| Display | Ahn et al., 2014 | One 55-inch screen vs. Three 55-inch screens | + | |

| Bracken, 2005 | Image quality (NTSC vs. HDTV) | + | ||

| James et al., 2011 | 30-inch LCD screen vs. rear-projection system on 13-foot dome | Null | ||

| Skalski and Whitbred, 2010 | Image quality (Standard vs. High Definition) | Null | ||

| Other | Chuah et al., 2013 (Study 1) | Low vs. High physicality | +* | *Moderated by plausibility |

| Hayes, 2015 | Static display vs. Motion control by tracking (Kinect) | Null | Positive for only for a few items | |

| Heidicker et al., 2017 | No tracking vs. Tracking vs. Tracking+ Inverse Kinematics | Null | Positive for only for two sub-factors | |

| Hills et al., 2005 | One view point vs. Multiple view points | – | ||

| Lee et al., 2016 | Incidental movement of real-virtual object (Absent vs. Present) | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2006a (Study 1) | Virtual social robot vs. Physical social robot | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2006a (Study 2) | Virtual social robot vs. Physical social robot | − | Tactile interaction restricted | |

| Li et al., 2016 | Human vs. robot virtual lecturer | – | ||

| Oh et al., 2016 | “Jaw flap” vs. Facial tracking vs. Exaggerated facial tracking | “Jaw flap”/Facial tracking < Exaggerated facial tracking | ||

| Tanaka et al., 2015 (Study 1) | Low vs. High Physicality | + | ||

| Wu et al., 2015 | Virtual bowling (exergame) vs. Physical bowling | + | ||

| Zibrek et al., 2017(Study 2) | Self-move vs. Other-move | Null | ||

| CONTEXT | ||||

| Personality/Traits of virtual human | Al-Natour et al., 2011 | Match between virtual shopping assistant and participant strategy | + | |

| Aymerich-Franch et al., 2012 | Match between participant's and avatar's voice | + | ||

| Bailenson and Yee, 2005 | Mimicry | + | ||

| Gong et al., 2007 (Study 1) | Group identity (Mismatch vs. Match) | +* | *Moderated by identification | |

| Gong et al., 2007 (Study 2) | Group identity (Mismatch vs. Match) | +* | *Moderated by identification | |

| Guadagno et al., 2011 | Perceived empathy | + | ||

| Han et al., 2016 | Self-disclosure | + | ||

| Jin, 2012 (Study 2) | Match between physical and virtual other | + | ||

| Kang and Gratch, 2014 | Self-disclosure (None vs. Low vs. High) | Low/None < High | ||

| Kim and Timmerman, 2018 | Supportive feedback (Not supportive vs. supportive) | + | ||

| Kothgassner et al., 2014 | Social inclusion (exclusion vs. inclusion) | Null | ||

| Kothgassner et al., 2017 | Social inclusion (exclusion vs. inclusion) | Null | ||

| Lee and Nass, 2005 (Study 1) | Match between computer agent and participant personality | + | ||

| Lee and Nass, 2005 (Study 2) | Match between content & personality manifested by voice | + | ||

| Lee and Oh, 2012 (Study 1) | Impersonal vs. personal disclosure | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2006b | Match between robot and participant personality | + | ||

| McGregor, 2018 | Impersonal vs. personal disclosure | +* | * Moderated by group identity and target gender | |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2010 | Same ethnicity vs. Different ethnicity | +* | *Moderated by gender | |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2010 | Same gender vs. Different gender | Null | ||

| Verhagen et al., 2014 | Expert | +* | *Moderated by task type | |

| Verhagen et al., 2014 | Friendly | +* | *Moderated by task type | |

| Verhagen et al., 2014 | Smiling | Null | ||

| Xu and Lombard, 2017 | Group identification | + | ||

| Agency | Appel et al., 2012 | Agent vs. Avatar | + | |

| Bailenson et al., 2003 (Study 2) | Agent vs. Avatar | + | ||

| Dalzel-Job, 2014 (Study 2) | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Felnhofer et al., 2018 | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Gajadhar et al., 2008 | Agent vs. Avatar | + | ||

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 2) | Agent vs. Avatar | +* | *Moderated by virtual human gender | |

| Hoyt et al., 2003 | Agent vs. Avatar | + | ||

| Kothgassner et al., 2014 | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Kothgassner et al., 2017 | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Peña et al., 2017 | Agent vs. Avatar | + | ||

| von der Pütten et al., 2010 | Agent vs. Avatar | Null | ||

| Physical proximity | Croes et al., 2016 | Same room vs. Different rooms | + | |

| Gajadhar et al., 2008 | Same room vs. Different rooms | + | ||

| Hatta and Ken-ichi, 2008 | Remote vs. close | +* | *Moderated by visibility | |

| Järvelä et al., 2016 | Same room vs. Different rooms | + | ||

| Jung et al., 2017 | Distant vs. Close (geolocation proximity) | + | ||

| Task type | de Greef, 2014 | Complex vs. Simple | +* | *Moderated by relationship |

| Herrewijn and Poels, 2015 | Be observer vs. Be Player vs. Collaborate | Observe/Play < Collaborate | ||

| Kim et al., 2013a | Human as care-giver vs. Robot as care-giver | + | ||

| Wu et al., 2015 | Competitive vs. Collaborative | Null | ||

| Social cues | Choi and Kwak, 2017 (Study 2) | Number of remote senders (single vs. multiple) | + | |

| Daher et al., 2016 | Exposure to other person interacting with VH (No vs. Yes) | + | ||

| Kim, 2016 | Number of different voices (single vs. multiple) | + | ||

| Kim and Sundar, 2014 | Online buddy (Absent vs. Present) | - | ||

| Lee and Nass, 2004 (Study 1) | Single voice vs. Multiple voices | + | ||

| Lee and Nass, 2004 (Study 2) | Single voice vs. Multiple voices | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2005 | Number of participants (individual vs. group) | Null | ||

| Robb et al., 2016 | Presence of human teammate (No vs. Yes) | Null | Null main effect, but significant interaction with role of virtual human | |

| Robb et al., 2016 | Role of virtual human (anesthesiologist vs. surgeon) | +* | *Only when there was no human teammate | |

| Identity cues | Choi and Kwak, 2017 (Study 1) | Telepresence robot: Low identity cues vs. High identity cues | +/− | Higher for robot, lower for remote sender |

| Choi and Kwak, 2017 (Study 2) | Telepresence robot: Low identity cues vs. High identity cues | +/− | Higher for robot, lower for remote sender | |

| Feng et al., 2016 | No personal cues vs. Name+Picture | + | ||

| Li et al., 2015 | Non-name ID vs. Picture+name ID | + | ||

| Schumann et al., 2017 | Non-name ID vs. Picture+name ID | + | ||

| Other | Alghamdi et al., 2016 (Study 1) | Multiple vs. Integrated communication channels | + | |

| Alghamdi et al., 2016 (Study 2) | Multiple vs. Integrated communication channels | + | ||

| Bouchard et al., 2013 | Relationship (Virtual animal vs. Unknown VH vs. Known VH) | + | ||

| Feng et al., 2016 | Gender of VH | Null | ||

| Horvath and Lombard, 2010 | No social pleasantries & picture vs. Social pleasantries & picture | + | ||

| Jin, 2011 | Match between regulatory strategy and task | + | ||

| Kang and Watt, 2013 | Non-anonymous vs. Anonymous partner | - | ||

| Kim et al., 2016 | Implausible vs. Plausible VH behavior | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2017 | Implausible vs. Plausible VH behavior | + | ||

| Yoo and Alavi, 2001 | Group cohesion (groups without vs. with a history) | + | ||

| INDIVIDUAL | ||||

| Demographic variables | Bailenson et al., 2006 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | |

| Bracken, 2005 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Cho et al., 2015 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| de Greef, 2014 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Felnhofer et al., 2014 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Giannopoulos et al., 2008 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 1) | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Hauber et al., 2005 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Johnson, 2011 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Lim and Richardson, 2016 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Lowden and Hostetter, 2012 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Nowak, 2003 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Qin et al., 2013 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2010 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Null | ||

| Richardson and Swan, 2003 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Thayalan et al., 2012 | Gender (Male vs. Female) | + | ||

| Cho et al., 2015 | Age | Null | ||

| Felnhofer et al., 2014 | Age | Null | ||

| Hauber et al., 2005 | Age | Null | ||

| Kim et al., 2004 | Age | – | ||

| Lim and Richardson, 2016 | Age | Null | ||

| Richardson and Swan, 2003 | Age | Null | ||

| Siriaraya and Ang, 2012 | Age | – | ||

| Psychological traits | Cortese and Seo, 2012 | Communication Apprehension | – | |

| Giannopoulos et al., 2008 | Shyness | – | ||

| Jin, 2010 | Interdependent self-construal | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2013a | Immersive Tendency | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2013a | Need to Belong | + | ||

| Kim et al., 2016 | Extraversion | + | ||

| Lee et al., 2006a | Loneliness | + | ||

| Lee and Shin, 2014 | Transportability | +* | *Moderated by modality | |

| Other | Cho et al., 2015 | Epistemological Belief (Simple vs. Complex) | + | |

| Gimpel et al., 2016 | Channel competence (experience comfort with medium) | + | ||

| Tanaka et al., 2015 (Study 2) | Previous interaction experience (No vs. Yes) | +* | *Moderated by physicality | |

Table 3.

| References | Publication outlet | N | Most recent impact factor | No. of Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2014 | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 144 | 2.689 | 4 |

| Al-Natour et al., 2011 | Journal of the Association for Information Systems | 181 | 2.839 | 61 |

| Alge et al., 2003 | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes | 198 | 2.259 | 322 |

| Alghamdi et al., 2016 (Study 1 & 2) | Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems | 67 & 50 | N/A | 2 |

| Appel et al., 2012 | Advances in Human-Computer Interaction | 90 | N/A | 25 |

| Axelsson et al., 2001 | Cyberpsychology and Behavior | 44 | 2.689 | 39 |

| Aymerich-Franch et al., 2012 | International Workshop on Presence | 51 | N/A | 12 |

| Bailenson and Yee, 2005 | Psychological Science | 69 | 6.128 | 493 |

| Bailenson et al., 2001 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 50 | 0.426 | 357 |

| Bailenson et al., 2003 (Study 1 & 2) | Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin | 80 & 80 | 2.498 | 491 |

| Bailenson et al., 2005 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 146 | 0.426 | 237 |

| Bailenson et al., 2006 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 30 | 0.426 | 252 |

| Basdogan et al., 2000 | ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction | 10 | 0.972 | 432 |

| Bente et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | International Workshop on Presence | 76 & 82 | N/A | 48 |

| Bente et al., 2008 | Human Communication Research | 150 | 2.364 | 354 |

| Bouchard et al., 2013 | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 42 | 2.689 | 30 |

| Bracken, 2005 | Media Psychology | 95 | 2.574 | 168 |

| Casanueva and Blake, 2001 (Study 1 & 2) | Annual Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists | 18 & 18 | N/A | 49 |

| Chellali et al., 2011 | Interacting with Computers | 60 | 0.809 | 24 |

| Cho et al., 2015 | Internet and Higher Education | 128 | 5.847 | 26 |

| Choi and Kwak, 2017 (Study 1 & 2) | Cognitive Systems Research | 60 & 72 | N/A | 1 |

| Choi et al., 2001 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | 210 | N/A | 139 |

| Christie, 1974 | European Journal of Social Psychology | 36 | N/A | N/A |

| Chuah et al., 2013 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 23 | 0.426 | 18 |

| Clayes and Anderson, 2007 | International Journal of Human-Computer Studies | 72 | 2.3 | 23 |

| Cortese and Seo, 2012 | Communication Research Reports | 152 | N/A | 13 |

| Croes et al., 2016 | Computers in Human Behavior | 210 | 3.536 | 6 |

| Daher et al., 2016 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 24 | N/A | – |

| Dalzel-Job, 2014 (Study 2) | The University of Edinburgh | 48 | N/A | – |

| de Greef, 2014 | International Workshop on Presence | 42 | N/A | – |

| de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001 | Cyberpsychology and Behavior | 34 | 2.689 | 121 |

| DeSchryver et al., 2009 | Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference | 31 | N/A | 140 |

| Dicke et al., 2010 | British Computer Society Interaction Specialist Group Conference | 82 | N/A | 2 |

| Felnhofer et al., 2014 | Computers in Human Behavior | 124 | 3.536 | 33 |

| Felnhofer et al., 2018 | Computers in Human Behavior | 95 | 3.536 | – |

| Feng et al., 2016 | Communication Research | 202 | 3.391 | 18 |

| Fortin and Dholakia, 2005 | Journal of Business Research | 360 | 2.509 | 516 |

| Francescato et al., 2006 | Computers in Human Behavior | 50 | 3.536 | 190 |

| Gajadhar et al., 2008 | International Conference of Fun and Games | 2006- | 0.402 | 125 |

| Garau et al., 2003 | Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) | 48 | N/A | 311 |

| Garau et al., 2005 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 41 | 0.426 | 145 |

| Giannopoulos et al., 2008 | International Conference on Human Haptic Sensing and Touch Enabled Computer Applications | 40 | 0.402 | 11 |

| Gimpel et al., 2016 | European Conference on Information Systems | 528 | N/A | 5 |

| Gong, 2008 | Computers in Human Behavior | 168 | 3.536 | 116 |

| Gong et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | Annual Conference of the International Communication Association | 53 & 64 | N/A | 3 |

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | Media Psychology | 65 & 174 | 2.574 | 216 |

| Guadagno et al., 2011 | Computers in Human Behavior | 38 | 3.536 | 45 |

| Han et al., 2016 | International Journal of Information Management | 809 | 4.516 | 14 |

| Hatta and Ken-ichi, 2008 | Computers in Human Behavior | 43 | 3.536 | 11 |

| Hauber et al., 2005 | International Workshop on Presence | 42 | N/A | 76 |

| Hauber et al., 2006 | ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) | 30 | N/A | 57 |

| Hauber et al., 2012 | The Open Software Engineering Journal | 36 | N/A | 7 |

| Hayes, 2015 | University of Central Florida | 20 | N/A | 1 |

| Heidicker et al., 2017 | IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces | 18 | N/A | 2 |

| Heldal et al., 2005 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 220 | N/A | 31 |

| Herrewijn and Poels, 2015 | Computers in Human Behavior | 121 | 3.536 | 12 |

| Hills, 2005 (Study 1 & Study 2) | University of Otago | 42 & 35 | N/A | 10 |

| Hills et al., 2005 | International Conference on Augmented Tele-Existence | 35 | N/A | 9 |

| Homer et al., 2008 | Computers in Human Behavior | 26 & 25 | 3.536 | 148 |

| Horvath and Lombard, 2010 | PsychNology Journal | 189 | N/A | 27 |

| Hoyt et al., 2003 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 48 | 0.426 | 125 |

| James et al., 2011 | The Ergonomics Open Journal | 10 | N/A | 1 |

| Järvelä et al., 2016 | Frontiers in Psychology | 61 | 2.089 | 3 |

| Jin, 2009 | Cyberpsychology and Behavior | 48 | 2.689 | 68 |

| Jin, 2010 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 179 | 0.426 | 23 |

| Jin, 2011 | Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media | 101 | 1.773 | 75 |

| Jin, 2012 (Study 2) | Computers in Human Behavior | 148 | 3.536 | 27 |

| Johnsen and Lok, 2008 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 27 | N/A | 22 |

| Johnson, 2011 | Journal of Organizational and End User Computing | 555 | 0.744 | 45 |

| Jordan et al., 2002 | International Workshop on Presence | 20 | N/A | 32 |

| Jung et al., 2017 | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 590 | 2.689 | 1 |

| Kang and Gratch, 2014 | Computers in Human Behavior | 171 | 3.536 | 11 |

| Kang and Watt, 2013 | Computers in Human Behavior | 196 | 3.536 | 15 |

| Kang et al., 2008 | Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 126 | N/A | 31 |

| Kim, 2016 | Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication | 100 | 4 | 6 |

| Kim et al., 2014 | Computers in Human Behavior | 80 | 3.536 | 13 |

| Kim et al., 2013a | Computers in Human Behavior | 60 | 3.536 | 45 |

| Kim et al., 2013b | Information and Management | 80 | 3.89 | 68 |

| Kim and Sundar, 2012 | Computers in Human Behavior | 93 | 3.536 | 60 |

| Kim and Sundar, 2014 | Computers in Human Behavior | 100 | 3.536 | 24 |

| Kim and Timmerman, 2018 | Journal of Media Psychology | 47 | 1.118 | 4 |

| Kim et al., 2004 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 20 | 0.426 | 146 |

| Kim et al., 2012 (Study 1 & 2) | Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) | 14 & 11 | NA | 79 |

| Kim et al., 2016 | International Conference on Artificial Reality and Tele-Existence | 31 | N/A | 2 |

| Kim et al., 2017 | Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds | 22 | 0.697 | 2 |

| Kothgassner et al., 2014 | International Workshop on Presence | 48 | N/A | – |

| Kothgassner et al., 2017 | Computers in Human Behavior | 45 | 3.536 | 4 |

| Lee, 2013 | Journal of Communication | 183 | 3.729 | 34 |

| Lee and Jang, 2013 (Study 1 & 2) | Communication Research | 143 & 100 | 3.391 | 57 |

| Lee and Nass, 2004 | Human Communication Research | 40 | 2.364 | 107 |

| Lee and Nass, 2005 (Study 1 & 2) | Media Psychology | 72 & 80 | 2.574 | 122 |

| Lee and Oh, 2012(Study 1) | Journal of Communication | 164 | 3.729 | 72 |

| Lee and Shin, 2012 | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 264 | 2.689 | 84 |

| Lee and Shin, 2014 | Communication Research | 217 | 3.391 | 54 |

| Lee et al., 2005 | Human Communication Research | 40 | 2.364 | 78 |

| Lee et al., 2006a | Journal of Communication | 48 | 3.729 | 238 |

| Lee et al., 2006b (Study 1 & 2) | International Journal of Human-Computer Studies | 32 & 32 | 2.3 | 176 |

| Lee et al., 2007 | International Workshop on Presence | 41 | N/A | 4 |

| Lee et al., 2016 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 20 | N/A | 11 |

| Lee et al., 2017 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 41 | N/A | 6 |

| Lee et al., 2018 | IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics | 26 | 3.078 | – |

| Li et al., 2015 | Communication Quarterly | 198 | N/A | 2 |

| Li et al., 2016 | Computers in Human Behavior | 40 | 3.536 | 27 |

| Lim and Lee-Won, 2017 | Telematics and Informatics | 128 | 3.789 | 5 |

| Lowden and Hostetter, 2012 | Computers in Human Behavior | 157 | 3.536 | 16 |

| McGregor, 2018 | New Media & Society | 1181 | 3.121 | 7 |

| Meyer and Lohner, 2012 | Annual Conference of the International Communication Association | 120 | N/A | – |

| Moreno and Mayer, 2004 | Journal of Educational Psychology | 48 | 4.433 | 317 |

| Mühlbach et al., 1995 (Study 1) | Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society | 32 | 2.371 | 123 |

| Nam et al., 2008 | Computers in Human Behavior | 36 | 3.536 | 27 |

| Nowak, 2003 | Media Psychology | 42 | 2.574 | 57 |

| Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 134 | 0.426 | 576 |

| Nowak et al., 2009 | Computers in Human Behavior | 142 | 3.536 | 36 |

| Oh et al., 2016 | PLOS One | 158 | 2.766 | 6 |

| Pan et al., 2008 | International Workshop on Presence | 33 | N/A | 8 |

| Park and Sundar, 2015 | Computers in Human Behavior | 108 | 3.536 | 17 |

| Peña et al., 2017 | Journal of Media Psychology | 216 | 1.118 | 2 |

| Phillips and Lee, 2005 (Study 3) | Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising | 71 | N/A | – |

| Qin et al., 2013 (Study 2) | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 20 | 0.426 | 6 |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2005 | International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction | 72 | 1.259 | 159 |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2010 | International Journal of Human-Computer Studies | 188 | 2.3 | 83 |

| Rauh and Renfro, 2004 | Annual Conference of the International Communication Association | 34 | N/A | 7 |

| Rauwers et al., 2016 | Computers in Human Behavior | 195 | 3.536 | 3 |

| Richardson and Swan, 2003 | Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks | 97 | N/A | 1855 |

| Robb et al., 2016 | Frontiers in ICT | 92 | NA | 1 |

| Sallnäs, 2010 | Haptics: Generating and Perceiving Tangible Sensations | 18 | 0.402 | 17 |

| Sallnäs, 2005 (Study 1) | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 60 | 0.426 | 119 |

| Sallnäs et al., 2000 | ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction | 14 | 0.972 | 382 |

| Schroeder et al., 2001 | Computers and Graphics | 132 | 1.2 | 150 |

| Schumann et al., 2017 (Study 2) | Computers in Human Behavior | 37 | 3.536 | 1 |

| Shahid et al., 2012 | Interacting with Computers | 88 | 0.809 | 25 |

| Shimoda, 2007 | Annual Conference of the International Communication Association | 51 | N/A | – |

| Siriaraya and Ang, 2012 | Interacting with Computers | 60 | 0.809 | 29 |

| Skalski and Tamborini, 2007 | Media Psychology | 235 | 2.574 | 88 |

| Skalski and Whitbred, 2010 | PsychNology Journal | 74 | N/A | 66 |

| Slater et al., 1999 | IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications | 10 | 1.64 | 192 |

| Slater et al., 2000 | Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments | 30 | 0.426 | 359 |

| Steed et al., 1999 | IEEE Virtual Reality Conference | 60 | N/A | 88 |

| Takatalo et al., 2011 | Media Psychology | 91 | 2.574 | 56 |

| Tanaka et al., 2015 | Frontiers in ICT | 36 & 16 | NA | 11 |

| Thayalan et al., 2012 | Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences | 51 | N/A | 7 |

| Verhagen et al., 2014 | Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication | 296 | 4 | 39 |

| Vishwanath, 2016 (Study 2) | Computers in Human Behavior | 104 | 3.536 | 8 |

| von der Pütten et al., 2010 | Computers in Human Behavior | 83 | 3.536 | 165 |

| Wideström et al., 2000 | International Conference on Collaborative Virtual Environments | 88 | N/A | 32 |

| Wu et al., 2014 | IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics | 22 | 3.078 | 17 |

| Wu et al., 2015 | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 113 | 2.689 | 14 |

| Xu, 2014 | Computers in Human Behavior | 152 | 3.536 | 72 |

| Yoo and Alavi, 2001 | Management Information Systems Quarterly | 135 | 5.43 | 724 |

| Zelenkauskaite and Bucy, 2009 | International Workshop on Presence | 67 | N/A | 2 |

| Zhan and Mei, 2013 | Computers and Education | 257 | 4.538 | 86 |

| Zibrek et al., 2017 (Study 1 & 2) | ACM Symposium on Applied Perception | 38 & 18 | N/A | 2 |

Impact factor was retrieved from Web of Science Journal Citation Reports on August 19, 2018.

Number of citations was retrieved from Google Scholar on August 19, 2018.

Materials and method

To collect studies that focused on the antecedents of social presence, we directly reviewed the archives of academic journals with a focus on virtual environments including Computers in Human Behavior; Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking; Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication; Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments; Frontiers in Robotics and AI, and conference proceedings from the International Society for Presence Researchers (ISPR) Conference and the IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality. We chose these outlets by selecting and expanding upon the outlets chosen in a recent meta-analysis on presence conducted by Cummings and Bailenson (2016). Based on concepts and terms that co-occurred frequently according to the subjective judgment of the researcher, we also conducted keyword searches in the EBSCO Host Communication & Mass Media databases, PsycNET, the Temple University ISPR Telepresence Literature Refshare database, and Google Scholar. Search terms included a combination of terms related to social presence, such as “social presence,” “co-presence,” “social richness,” “computers as social actors,” “virtual reality,” “virtual environments,” and “immersion” in addition to predictors that we identified during our search including “modality,” “HMD,” “realism,” “stereoscopy,” “haptics,” “audio,” “display,” “tracking,” “gender,” “agency,” and “proximity.”

Once the candidate studies were identified, we selected studies that (1) used at least one self-report measure of social presence (or the synonymous concept of co-presence); if social presence and co-presence were measured separately, we considered both measures in our review, (2) included experimental manipulations and/or questionnaire items (e.g., personality, gender, etc.) that were used to assess the predictors of social presence, and (3) conducted quantitative analyses to determine whether a predictor significantly influenced perceptions of social presence.

Studies that measured social presence with related but distinct constructs (e.g., interactivity, positive affect, social influence, telepresence, interpersonal attraction, electronic propinquity) were not included, as they do not uniquely measure the extent to which one feels as if she is present with a sentient being. Similarly, concepts that share theoretical similarities with, but do not uniquely measure social presence, were excluded. One significant concept that was not included due to this criterion was plausibility illusion (Slater, 2009). Plausibility illusion refers to the credibility of the events that are unfolding in the virtual environment. According to Slater (2009), plausibility illusion is orthogonal to the “sense of being there,” which is conceptualized as place illusion. Plausibility illusion shares similarities with social presence as it captures the extent to which the user feels that he or she is interacting with an actual social being (Biocca et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006a). However, plausibility illusion also includes dimensions other than social presence because the concept simultaneously captures the credibility of various aspects of a virtual scenario, not just the virtual human (Slater et al., 2010).

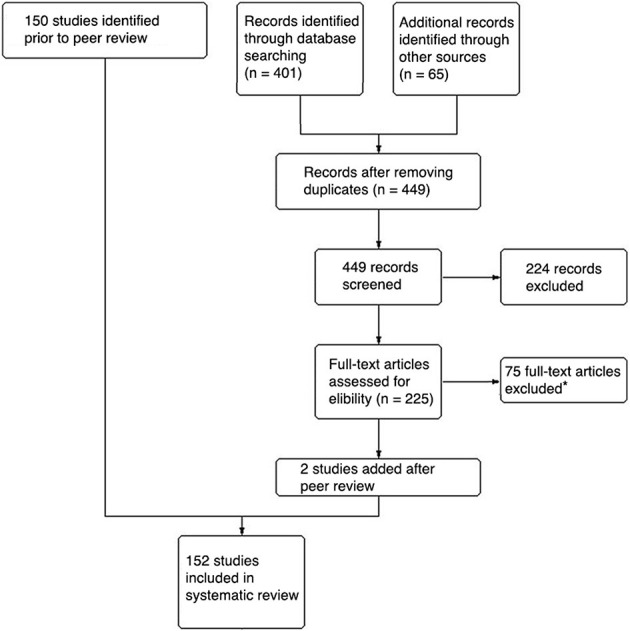

Finally, while we are aware of the strengths of behavioral and physiological measures and limitations of self-report measures (Slater, 2004; Friedman et al., 2006), we did not include studies that exclusively used behavioral and/or physiological measures of social presence to reduce variance and maximize internal validity when comparing study findings. The criteria used to select studies were adapted from Cummings and Bailenson (2016) to fit the current context. Based on this process (Figure 1), we were able to identify 152 studies with 233 separate findings regarding the factors that can predict social presence. When discussing the results, we assumed that the findings of the studies were true and correct.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study identification. *Social presence is not a dependent variable: 27; No quantitative self-report measure of social presence: 24; Review article: 9; General presence is measured: 6; Work-in-progress: 3; Measure not reported: 1; Conference presentation of published article: 5.

Findings: what predicts social presence?

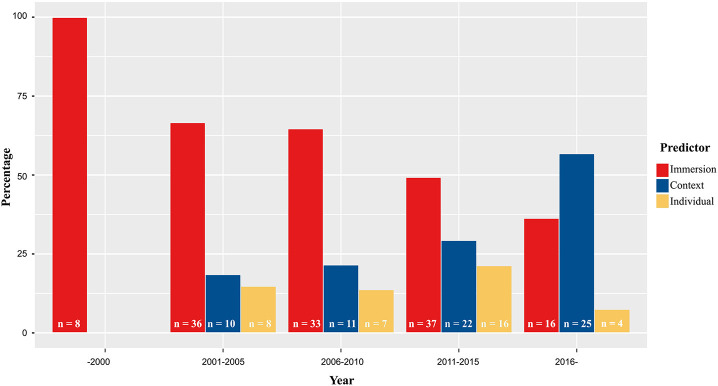

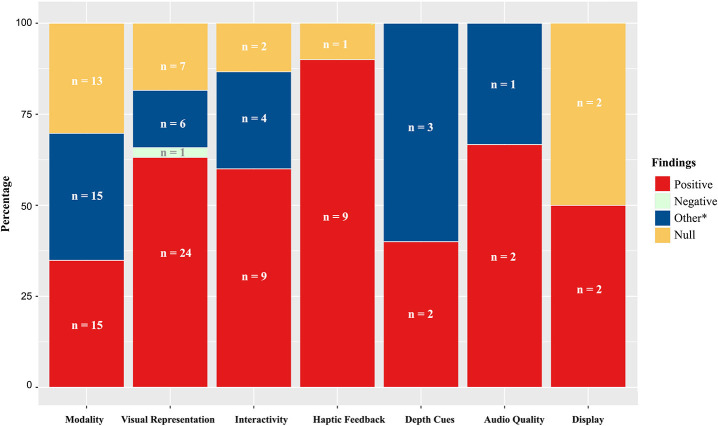

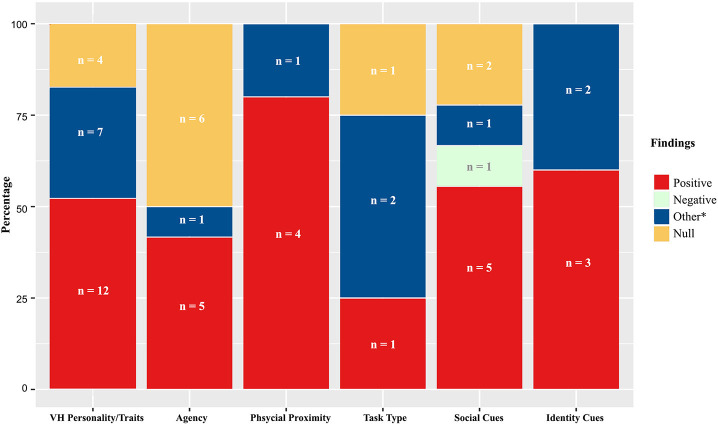

Considering that social presence was initially considered to be an inherent quality of a communication medium (Short et al., 1976), it is natural that a significant body of research explored how modality influences social presence. For similar reasons, the technological affordances that enable the reproduction of various social cues (e.g., presence of a visual representation, haptic feedback, etc.) have received considerable attention as potential antecedents of social presence. However, while earlier studies on the predictors of social presence focused almost entirely on immersive qualities, more recent studies also consider the impact of contextual and individual factors, perhaps as an acknowledgment of social presence as a subjective experience. The following sections will thus categorize and discuss the predictors of social presence using three overarching categories that emerged while conducting the systematic review: immersive qualities, contextual properties, and individual traits.

Immersive qualities and social presence

General modality

Much of the earlier social presence research focused on how modalities with varying levels of immersion afford different levels of presence. It is important to note that while research on general modality does offer insight into how certain technological features (e.g., depth cues, display, stereoscopy) might influence social presence, it compares media that vary across multiple features, which makes it difficult to isolate the affordance(s) that influenced perceptions of social presence. This camp of research is well-aligned with the traditions of social presence theory (Short et al., 1976) and media richness theory (Daft and Lengel, 1986) in that they are grounded on the assumption that the technological qualities of a medium afford different levels of social presence. In their meta-analysis on the impact of immersion on telepresence, Cummings and Bailenson (2016) similarly found that general modality (e.g., comparing an HMD with head-tracking to a desktop computer) was one of the most frequently studied predictors of telepresence.

As can be seen in Table 1, research on the impact of modality on social presence to date most often compares (1) CMC with FtF communication, (2) text-based CMC with other forms of audiovisual modalities, and (3) immersive virtual environments with non-immersive virtual environments. Although it is less common, a small number of studies also compare different types of virtual environments (e.g., Heldal et al., 2005; Johnsen and Lok, 2008).

Because FtF interaction is considered to be the gold-standard for social presence (Biocca et al., 2001), a considerable amount of research compares FtF communication with CMC to determine how successful a given system is at establishing a social presence. Most of these studies found that communicators experience lower levels of social presence during CMC compared to FtF conversations. For example, Cortese and Seo (2012) found that CMC participants felt less social presence than FtF participants while they were discussing issues mentioned in a news article for 20 min. More specifically, the researchers operationalized social presence to assess both how sociable their partner was and how “co-located” they felt with their partner, and found that FtF communicators experienced higher levels of social presence compared to their CMC counterparts. Similar results were found in online learning contexts (Zhan and Mei, 2013) and decision-making scenarios (Biocca et al., 2001; Alge et al., 2003). One exception to this trend was Francescato et al. (2006) study, which found no differences in perceived social presence between students who completed a seminar series online, compared to those who completed the same seminar face-to-face. It is important to note, however, that participants completed the seminar series over a period of 2 months. This extended experiment period may be why the authors did not find a difference between CMC and FtF conditions. Just as Walther (1992) found that granting additional time to CMC interactants led to equally desirable communication outcomes as their FtF counterparts, the 2-month period employed by Francescato et al. (2006) may have been sufficient for both groups of participants to adapt their communication strategies to the given platforms and attain similar levels of social presence.

Studies that compared text-based CMC with more vivid forms of communication modalities (e.g., audio, video, avatar) also found that participants felt the lowest level of social presence when communicating via text-based CMC compared to “richer” forms of media, when given the same amount of time (e.g., Bente et al., 2008; Appel et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013b). For example, Bente et al. (2008) measured how much social presence participants felt while selecting the best job candidate out of a pool of six applicants in a text chat, audio, audio with video, or avatar communication platform. They found that participants in the text chat condition felt significantly less social presence when compared with participants who communicated via other modalities. Similarly, studies that compared text-based CMC with modalities that offered audiovisual cues, such as videoconferencing (Sallnäs, 2005; Kim et al., 2014), avatar-mediated communication, and audio communication (Kim et al., 2013b) generally found that text-based CMC elicits lower social presence than modalities that offer additional audiovisual cues.

While audio and video modalities appear to have a clear advantage over text-based CMC, the strength of audiovisual modalities over audio-only modalities is less clear. Of the nine studies identified in Table 1 (de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001; Yoo and Alavi, 2001; Sallnäs, 2005, Study 1 & 2; Bailenson et al., 2006; Bente et al., 2008; Homer et al., 2008; de Greef, 2014; Gimpel et al., 2016) that offered a comparison between audio-only and audio-video modalities, only four found that the addition of video increased perceptions of social presence (de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001; Yoo and Alavi, 2001; de Greef, 2014; Gimpel et al., 2016). While the sample size is small (n = 9), these results suggest that linear increments of immersion do not necessarily lead to corresponding increases in social presence. Considering that two of the studies (de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001; de Greef, 2014) that did find that adding video increased social presence required participants to complete a visual task, while the studies that did not find differences between the audio-only and audio-video conditions provided participants with tasks that had a weaker visual component (e.g., decision-making task, interview task), it is possible that the nature of the task moderates the benefits of adding video to audio. Table 2 shows details of these studies.

Table 2.

Summary of study information.

| Reference | Social presence measurement | Task(s) | Target (AP, CA) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2014 | Temple Presence Inventory (Lombard et al., 2009) | View a virtual character on a screen | CA | Korea |

| Al-Natour et al., 2011 | Gefen and Straub, 2003 | Online shopping task | CA | Canada |

| Alge et al., 2003 | Custom construct | Collaborate in teams of 3 on two tasks (brainstorming and solution-seeking) | AP | USA |

| Alghamdi et al., 2016 (Study 1 & 2) | Short et al., 1976 | Tidy up a virtual house | AP | New Zealand |

| Appel et al., 2012 | Bailenson et al., 2001; Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | Interact with agent (but framed as agent or avatar) | CA | USA |

| Axelsson et al., 2001 | Custom construct | Complete a Rubik's cube-type puzzle | AP | Sweden |

| Aymerich-Franch et al., 2012 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Give a speech to a virtual audience | CA | USA |

| Bailenson and Yee, 2005 | Slater et al., 2000 | Listen to agent presentation | CA | USA |

| Bailenson et al., 2001 | Custom construct | Walk up to virtual human, read and memorize information on front/back tags | CA | USA |

| Bailenson et al., 2003 (Study 1 & 2) | Custom construct | Approach virtual human (Study 1)/Observe virtual human approach participants (Study 2) | CA | USA |

| Bailenson et al., 2005 | Custom construct | Look at virtual agent | CA | USA |

| Bailenson et al., 2006 | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | Interact with partner & Emoting task | AP | USA |

| Basdogan et al., 2000 | Custom construct | Move a ring with the help of a partner without touching the wire | AP | USA |

| Bente et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | Get-acquainted task | AP | Germany |

| Bente et al., 2008 | Biocca et al., 2001; Nowak, 2001; Kumar and Benbasat, 2002; Tu, 2002 | Hire the most suitable job candidate (Management decision task) (hire most suitable job candidate) | AP | Germany |

| Bouchard et al., 2013 | Gerhard et al., 2001; Bailenson et al., 2005 | Interact with a virtual cat, view virtual humans in pain | CA | Canada |

| Bracken, 2005 | Lombard et al., 2000 | Watch a video (The Beauty of Japan) | AP | USA |

| Casanueva and Blake, 2001 (Study 1 & 2) | Custom construct | In groups of 3 participants, read a story and collaboratively rank the characters | AP | South Africa |

| Chellali et al., 2011 | Not reported | Perform a needle insertion task in dyads after training session | AP | France |

| Cho et al., 2015 | Wei and Chen, 2012 | Take online course on Second Life | AP | Singapore |

| Choi and Kwak, 2017 (Study 1 & 2) | Short et al., 1976; Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Engage in a video call with a remote participant using a telepresence robot | AP | Korea |

| Choi et al., 2001 | Short et al., 1976; Lombard, 1995 | Navigate an advertising website | CA | USA |

| Chuah et al., 2013 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Anesthesiologists interact with two embodied conversational agents (nurse & patient's daughter) | CA | USA |

| Christie, 1974 | Custom construct | Discuss a modern business issue | AP | UK |

| Clayes and Anderson, 2007 | Short et al., 1976 | Participates complete focused and non-focused tasks in groups of three people | AP | Scotland |

| Cortese and Seo, 2012 | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | View news website and discuss issues | AP | USA |

| Croes et al., 2016 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Get-acquainted task | AP | The Netherlands |

| Daher et al., 2016 | Harms and Biocca, 2004 | Play a guessing game | CA | USA |

| Dalzel-Job, 2014 (Study 2) | Custom construct | Carry out 10 tasks in a virtual environment with a partner | AP | Scotland |

| de Greef, 2014 | IPO-Social Presence Questionnaire (de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001) | Select pictures with partner based on instructions | AP | The Netherlands |

| de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001 | IPO-Social Presence Questionnaire (de Greef and Ijsselsteijn, 2001) | Use a PhotoShare application with partner | AP | The Netherlands |

| DeSchryver et al., 2009 | Richardson and Swan, 2003 | Participate in online discussion forum for psychology class | AP | USA |

| Dicke et al., 2010 | Custom construct | Listen to an audio recording of multiple speakers | AP | Finland |

| Felnhofer et al., 2014 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Navigate in a café in an IVE and interact with a waiter and a stranger | CA | Austria |

| Felnhofer et al., 2018 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Navigate in a café in an IVE and interact with a waiter and a stranger | CA | Austria |

| Feng et al., 2016 | Lee and Nass, 2005 | Read supporter seeker's profile and respond on an online forum | AP | USA |

| Fortin and Dholakia, 2005 | Short et al., 1976 | View online ad and surf website | CA | USA |

| Francescato et al., 2006 | Cuddetta et al., 2003 | Complete small-group exercises as part of a seminar series | AP | Italy |

| Gajadhar et al., 2008 | Social Presence in Gaming Questionnaire (IJsselsteijn et al., 2008) | Play game with partner | AP | The Netherlands |

| Garau et al., 2003 | Custom construct | Participate in a role-playing negotiation task | AP | UK |

| Garau et al., 2005 | Custom construct | Enter virtual room and observe surroundings | CA | UK |

| Giannopoulos et al., 2008 | Basdogan et al., 2000 | Solve a jigsaw puzzle with a partner | AP | Spain |

| Gimpel et al., 2016 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Interact with a digital service agent (while applying for fictitious credit card) | AP | Germany |

| Gong, 2008 | Short et al., 1976 | Interact with virtual agent on how to respond to dilemma scenarios | CA | USA |

| Gong et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | Short et al., 1976 | Interact with virtual agent on an e-commerce website | CA | USA |

| Guadagno et al., 2007 (Study 1 & 2) | Swinth and Blascovich, 2001 | Listen to agent presentation | CA | USA |

| Guadagno et al., 2011 | 6-item questionnaire (details not reported) | Interact with a virtual peer counselor | CA | USA |

| Han et al., 2016 | Gefen and Straub, 2003 | View (fictitious) corporate Twitter accounts | AP | Korea |

| Hatta and Ken-ichi, 2008 | Short et al., 1976 | Negotiate on the price of a used car | AP | Japan |

| Hauber et al., 2005 | Short et al., 1976; Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Desert survival task | AP | New Zealand |

| Hauber et al., 2006 | Short et al., 1976 | Collaborative photo-matching task | AP | New Zealand |

| Hauber et al., 2012 | Short et al., 1976 | Collaborative celebrity-quote matching task | AP | New Zealand |

| Hayes, 2015 | Bailenson et al., 2006 | Deliver a lesson to virtual students | CA | USA |

| Heidicker et al., 2017 | Biocca et al., 2001 | Desert survival task | AP | Germany |

| Heldal et al., 2005 | Custom construct | Complete a Rubik's cube-type puzzle | AP | Sweden |

| Herrewijn and Poels, 2015 | Social Presence in Gaming Questionnaire (IJsselsteijn et al., 2008) | Play a multiplayer game | AP | Belgium |

| Hills, 2005 (Study 1) | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Short et al., 1976; Biocca et al., 2001) | Desert survival task | AP | New Zealand |

| Hills, 2005 (Study 2) | Short et al., 1976 | Build a virtual house with a partner | AP | New Zealand |

| Hills et al., 2005 | Short et al., 1976 | Evaluate five house designs | AP | New Zealand |

| Homer et al., 2008 | Kim and Biocca, 1997 | Viewed computer-based multimedia presentation of lecture | AP | USA |

| Horvath and Lombard, 2010 | Temple Presence Inventory (Lombard et al., 2009) | Test an interactive website for the submission of college admission application | CA | USA |

| Hoyt et al., 2003 | Custom construct | Categorization task & pattern recognition task | CA | USA |

| James et al., 2011 | Custom construct | Mining operators collaborate to move a mining vehicle through a maze | AP | Australia |

| Järvelä et al., 2016 | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Harms and Biocca, 2004) | View a video | AP | Finland |

| Jin, 2009 | Custom construct | View a virtual Apple store representative agent | CA | USA |

| Jin, 2011 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Interact with health consultant avatar | AP | USA |

| Jin, 2010 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Interact with a recommendation agent on Second Life | CA | USA |

| Jin, 2012 Study 2 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | FtF communication, followed by Avatar-to-Avatar communication | AP | USA |

| Johnsen and Lok, 2008 | Bailenson et al., 2005 | Interview virtual patient | CA | USA |

| Johnson, 2011 | Custom construct | Take online course | AP | USA |

| Jordan et al., 2002 | Basdogan et al., 2000 | Lift a cube with a virtual partner and keep it off the “ground” for as long as possible | AP | UK/USA |

| Jung et al., 2017 | Custom construct | View online dating site profile | AP | USA |

| Kang and Gratch, 2014 | Short et al., 1976 | Interview-style interaction | CA | USA |

| Kang and Watt, 2013 | Custom construct | Interact with partner on a mobile phone | AP | USA |

| Kang et al., 2008 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Interact with partner on a mobile phone | AP | USA |

| Kim, 2016 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Listen to information about local weather, traffic, and events | CA | China |

| Kim and Sundar, 2012 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Browse sunscreen company website | CA | USA |

| Kim and Sundar, 2014 | Gefen and Straub, 2003 | Participate in an interactive online health community | AP | USA |

| Kim and Timmerman, 2018 | Short et al., 1976; Lombard et al., 2000 | Play an exergame (Nintendo Wii Fit Hula Hoop game) | CA | USA |

| Kim et al., 2014 | Short et al., 1976 | Online chat (listen to a story) | AP | USA |

| Kim et al., 2013a | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Interact with a Nao robot | CA | Korea |

| Kim et al., 2013b | Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | Interact with a partner in an online apparel store and choose an item | AP | Korea |

| Kim et al., 2004 | Basdogan et al., 2000 | Lift a box with a virtual partner | AP | UK |

| Kim et al., 2012 (Study 1) | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | View a virtual human and indicate where he/she is looking or pointing | AP | Canada |

| Kim et al., 2012 (Study 2) | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | View a virtual instructor in a yoga pose and instruct a partner to reproduce the pose | AP | Canada |

| Kim et al., 2016 | Bailenson et al., 2003; Harms and Biocca, 2004 | Answer questions from a virtual human (MBTI personality test) | CA | USA |

| Kim et al., 2017 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Answer questions from a virtual human (MBTI personality test) | CA | USA |

| Kothgassner et al., 2014 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Play a ball-tossing game | CA | Austria |

| Kothgassner et al., 2017 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Play a ball-tossing game | CA | Austria |

| Lee, 2013 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003; Lee and Nass, 2005 | View politician on Twitter or on television | AP | Korea |

| Lee and Jang, 2013 (Study 1 & 2) | Lee and Nass, 2005 | View politician's Twitter page or newspaper interview | AP | Korea |

| Lee and Nass, 2004 | Custom construct | Listen to online reviews | CA | USA |

| Lee and Nass, 2005 (Study 1 & 2) | Custom construct | Listen to online reviews | CA | USA |

| Lee and Oh, 2012 (Study 1) | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | View politician's Twitter page | AP | Korea |

| Lee and Shin, 2012 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003; Lee and Nass, 2005 | View politician's Twitter page | AP | Korea |

| Lee and Shin, 2014 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003; Lee and Nass, 2005 | View politician's Twitter page or newspaper interview | AP | Korea |

| Lee et al., 2005 | Biocca et al., 2001 | Interact with an Aibo robot | CA | USA |

| Lee et al., 2006a | Custom construct | Interact with an Aibo robot | CA | USA |

| Lee et al., 2006b (Study 1 & 2) | Custom construct | Interact with virtual or physical social robot without (Study 1) or without (Study 2) tactile restrictions | CA | USA |

| Lee et al., 2007 | Custom construct | Participate in an educational quiz game | AP | Korea |

| Lee et al., 2016 | Harms and Biocca, 2004 | Play 20 questions with a virtual human | CA | USA |

| Lee et al., 2017 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Observe a virtual human walk, approach the participant, and leave | CA | USA |

| Lee et al., 2018 | Basdogan et al., 2000; Bailenson et al., 2003 | Walk around a virtual or real human that is engaging in various behaviors (standing, jumping, walking) | CA | USA |

| Li et al., 2015 | Lee and Nass, 2005 | Read a support-seeking post and type/post responses | AP | USA |

| Li et al., 2016 | Lee et al., 2006a,b | Watch an online lecture | CA | USA |

| Lim and Lee-Won, 2017 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003; Lee and Nass, 2005; Lee and Shin, 2014 | View a (fictitious) food company's Twitter feed | AP | USA |

| Lowden and Hostetter, 2012 | Hostetter and Busch, 2006 | Answer survey regarding videoconferencing experience | AP | USA |

| McGregor, 2018 | Lee and Oh, 2012 | View a screenshot of a political candidate's Twitter feed | AP | USA |

| Meyer and Lohner, 2012 | Gunawardena, 1995; Swan, 2002 | Watch an online news video | AP | USA |

| Moreno and Mayer, 2004 | Custom construct | Receive a lesson on botany from computerized agent | CA | USA |

| Mühlbach et al., 1995 (Study 1) | Custom construct | Collaborative decision-making task and negotiating task via videoconference | AP | Germany |

| Nam et al., 2008 | Schroeder et al., 2001 | Play air hockey game with remote partner | AP | USA |

| Nowak, 2003 | Short et al., 1976 | Desert survival task with text-based CMC | AP | USA |

| Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Custom construct | Get to know partner and compete in a virtual scavenger hunt | CA | USA |

| Nowak et al., 2009 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Prepare an oral report in groups of 3-4 students over 5 weeks | AP | USA |

| Oh et al., 2016 | Networked Minds (Harms and Biocca, 2004) | Play 20 questions and get acquainted with a virtual partner | AP | USA |

| Pan et al., 2008 | Custom construct | Listen to agent presentation | CA | UK |

| Park and Sundar, 2015 | Networked Minds (Harms and Biocca, 2004) | Interact with a customer service agent | CA | Korea |

| Peña et al., 2017 | Networked Minds (Harms and Biocca, 2004) | Play a video game in a single-player or multi-player mode | CA & AP | Korea |

| Phillips and Lee, 2005 (Study 3) | Choi et al., 2001 | View website with spokes-character | CA | USA |

| Qin et al., 2013 (Study 2) | Witmer and Singer, 1998; Kim et al., 2004 | Collaborate with a partner to complete a ring-moving task | AP | China |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2005 | Short et al., 1976 | Browse online electronics store, interact with customer service agent, and purchase items | AP | Canada |

| Qiu and Benbasat, 2010 | Gefen and Straub, 2003 | Interact with product recommendation agent | CA | Canada |

| Rauh and Renfro, 2004 | Short et al., 1976 | Participants talk with each other about a set of topics using a videoconferencing system | AP | USA |

| Rauwers et al., 2016 | Gefen and Straub, 2003; Lee et al., 2011 | Interact with a digital magazine | CA | USA |

| Robb et al., 2016 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Medical practitioners work with a virtual surgeon and a virtual anesthesiologist to prepare for surgery | CA | USA |

| Richardson and Swan, 2003 | Custom construct | Take online course | AP | The Netherlands |

| Sallnäs, 2005 (Study 1) | Short et al., 1976 & Custom construct | Decision-making task | AP | Sweden |

| Sallnäs, 2010 | (Short et al., 1976) modified | Pass cubes without audio communication | AP | Sweden |

| Sallnäs et al., 2000 | (Short et al., 1976) modified | Perform multiple collaborative tasks with virtual blocks | AP | Sweden |

| Schroeder et al., 2001 | Custom construct | Complete a Rubik's cube-type puzzle | AP | Sweden |

| Schumann et al., 2017 (Study 2) | Rüggenberg, 2007; Park and Sundar, 2015 | Collaborate with a student from a different university (confederate) to develop ideas for an event | AP | Belgium |

| Shahid et al., 2012 | Garau et al., 2001; Biocca and Harms, 2002 | Play game with partner | AP | The Netherlands |

| Shimoda, 2007 | Short et al., 1976 | Participate in a multi-session online system that delivers messages that encourages smokers to quit | CA | USA |

| Siriaraya and Ang, 2012 | Slater et al., 2000; Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Select avatar and interact with partner | AP | UK |

| Skalski and Tamborini, 2007 | Nowak and Biocca, 2003 | Listen to health information | CA | USA |

| Skalski and Whitbred, 2010 | Lombard et al., 2009 | Play a shooter game | CA | USA |

| Slater et al., 1999 | Custom construct | Give a presentation to a virtual audience | CA | UK |

| Slater et al., 2000 | Custom construct | Word puzzle & monitor group member (for some participants) | AP | UK |

| Steed et al., 1999 | Custom construct | Collaborate in groups of three to carry out a puzzle-solving task. | AP | UK & Greece |

| Takatalo et al., 2011 | Takatalo, 2002 | Play a first-person driving game for 40 minutes | CA | Finland |

| Tanaka et al., 2015 | Nakanishi et al., 2008 | Talk with a remote partner about an issue | AP | Japan |

| Thayalan et al., 2012 | Custom construct | Take online course | AP | Malaysia |

| Verhagen et al., 2014 | Yoo and Alavi, 2001 | Interact with virtual customer service agent | CA | The Netherlands |

| Vishwanath, 2016 (Study 2) | Slater et al., 1998 | Simulated phishing attack | AP | Singapore |

| von der Pütten et al., 2010 | (Bailenson et al., 2001) and Networked Minds Questionnaire (Biocca et al., 2001) | Interact with Rapport Agent | CA | USA |

| Wideström et al., 2000 | Custom construct | Complete a Rubik's cube-type puzzle | AP | Sweden |

| Wu et al., 2014 | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Complete 4 nurse shifts for a virtual patient | CA | USA |

| Wu et al., 2015 | Social Presence in Gaming Questionnaire (IJsselsteijn et al., 2008) | Bowl with a team on an exergame platform or with an indoor bowling set | AP | Singapore |

| Xu, 2014 | Short et al., 1976 | Read online reviews | AP | USA |

| Yoo and Alavi, 2001 | Short et al., 1976 | ”Van Management“ task (Mennecke and Wheeler, 1993) | AP | USA |

| Zelenkauskaite and Bucy, 2009 | Custom construct | Watch four videos of a politician | AP | USA |

| Zhan and Mei, 2013 | Social Presence Inventory (Biocca and Harms, 2002) | Take a course online or offline | AP | China |

| Zibrek et al., 2017 (Study 1 & 2) | Bailenson et al., 2003 | Approach a virtual character | CA | Ireland |

AP, Actual person; includes “fictitious” people if all of the virtual content was directly generated by an actual person (e.g., Twitter account of a fictitious politician).

CA, Computer algorithm; includes instances wherein pre-programmed messages and/or animations were selected by a human controller (“Wizard of Oz” technique; Kim et al., 2016).

A small number of studies (e.g., Steed et al., 1999; Slater et al., 2000; Moreno and Mayer, 2004) have also compared immersive virtual platforms (e.g., HMD, cave automatic virtual environment; CAVE) with non-immersive ones (e.g., Desktop). While the literature shows a general consensus that immersive virtual environments are more likely to generate greater feelings of telepresence compared to non-immersive virtual platforms (Cummings and Bailenson, 2016), this does not appear to be the case for social presence. Among the 10 studies that we identified, only two studies found significant differences in social presence between an immersive platform and a non-immersive one (Schroeder et al., 2001; Heldal et al., 2005). These results, coupled with the fact that the addition of video does not consistently increase one's sense of social presence, suggest that once a threshold is met, increasing the immersive quality of a modality does not automatically lead to increased social presence. As such, it may be both theoretically and practically important to isolate features and explore the extent to which each feature does (or does not) contribute to increasing social presence to further understand the dimensions of immersion that affect social presence.

Visual representation