Abstract

The ubiquity of digital communication within the high-risk drinking environment of college students raises exciting new directions for prevention research. However, we are lacking relevant constructs and tools to analyze digital platforms that serve to facilitate, discuss, and rehash alcohol use. In the current study, we introduce the construct of alcohol-talk (or the extent to which college students use alcohol-related words in text messaging exchanges) as well as introduce and validate a novel tool for measuring this construct. We describe a closed-vocabulary, dictionary-based method for assessing alcohol-talk. Analyses of 569,172 text messages from 267 college students indicate that this method produces a reliable and valid measure that correlates as expected with self-reported alcohol and related risk constructs. We discuss the potential utility of this method for prevention studies.

We are living in an age of digital connections, in which virtually all adults own a cellular phone (95% of all adults, 100% of young adults) and use the internet (89% of all adults, 98% of young adults; Pew Research Center, 2018b, 2018a). Digital communication devices are used to connect with a variety of social partners, and the content of digital communications offers insight into the social etiology of risky behaviors, with profound implications for prevention. Recent evidence suggests that posting alcohol-related content on social media (i.e. Facebook, Myspace, Twitter) is related to greater self-reported alcohol use and misuse (Fournier & Clarke, 2011; Moreno & Whitehill, 2014; Westgate et al., 2014). Much less empirical research exists on text messaging, but emerging research suggests that college students prefer the more private text message medium for coordinating and facilitating alcohol involvement to more public-facing social media sites (Jensen et al., 2018). To date, studies of alcohol-related content on social media have largely relied on either self-report of alcohol-related posting frequency (which is subjective) or objective hand-coding of alcohol-related posts (which is laborious and time intensive). Neither of these methods takes full advantage of the wealth of information on alcohol involvement contained within digital communications. Quantitative methods for more efficiently mining big data are rapidly evolving (Chen & Wojcik, 2016; Kosinski et al., 2016), but many still require considerable technological and quantitative skill to employ, making it difficult to identify and measure reasonable prevention targets.

A more user-friendly method for efficient quantitative text analysis is the closed-vocabulary, dictionary-based method that allows the user to count the number of occurrences of words from pre-defined categories (Kern et al., 2016; Mehl, 2006). A commonly-used platform for the dictionary-based approach is the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count program (LIWC; Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015), which comes with a number of native dictionaries tapping psychological constructs like positive and negative emotion words. The utility of dictionary-based methods like LIWC, however, is limited by the number of constructs for which dictionaries exist.

Given the role of digital communications in facilitating, discussing, and rehashing alcohol use (Hebden et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2018), a dictionary of alcohol-related words is needed for the study of online alcohol-related communications, but is not currently publicly available. This gap in the literature not only reduces our ability to understand the nature of digital communication in relation to drinking but also to define important constructs that may be important in future prevention efforts. The present study addresses this need by developing and validating a dictionary of alcohol-related words that comprise the construct of “alcohol-talk”, or the extent to which (college) students text one another using alcohol-related content. This study tests the validity of the alcohol-talk dictionary in a sample of 267 college students who contributed all of their text messages from a two-week period alongside timeline follow-back reports of their alcohol use during an overlapping 10-day period and self-reports on alcohol-related risks (including parent and peer substance use norms). College students are an ideal population in which to examine technology and drinking as they lay at the nexus of ubiquitous digital communication and alcohol misuse (Johnston et al., 2011a; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012; White & Hingson, 2013).

The Current Study

We developed the “alcohol-talk” dictionary for use in LIWC following a process guided by the recommendations of Pennebaker and colleagues (Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015). This process included generating a master list of relevant terms that define a construct (i.e., word collection phase), refining the list through expert judges (i.e., the judging phase), and evaluating the reliability and validity of the dictionary when used to define the construct of interest through LIWC.

For the current study, the word collection phase involved a panel of 4 undergraduate student advisors (diverse on gender and race/ethnicity) who generated a list of alcohol-related words using a mind mapping software that allowed them to loosely group words into sub-categories and spur brainstorming of other related words. The LIWC program allows for multi-word phrases (e.g. “shot glass”), which advisors were encouraged to include when relevant. Advisors used any and all resources available to them (including the internet and peers’ suggestions), and they were encouraged to include alternate spellings and common mis-spellings when appropriate. This list generated by the advisors was further augmented by words drawn from online thesauri and lists of slang words. This initial word collection phase yielded 697 examples of alcohol-talk.

Next, a second panel of judges (1 undergraduate, 1 graduate student, and 1 recent graduate; diverse on gender and race/ethnicity) reviewed the initial word collection to determine goodness of fit of each word with the alcohol-talk construct. They removed words that most commonly referenced not alcohol-related constructs or that lacked face validity. They also added new words that had been omitted. Finally, because the LIWC program allows for stemming of words to include alternate word endings (e.g. the stem “alcohol*” may be followed by “ic” or “ism”; “drunk*” may be followed by “s”, “ard”, or “est”), the panel of judges added stems to appropriate entries (which resulted in the combination of several variants of the same word into a single stemmed entry). Consensus within the panel was required for words to be retained in the final list of 524 alcohol-talk words. This alcohol-talk dictionary can be found in Table 3 and the LIWC dictionary can be downloaded at LINK TO BE INCLUDED LATER.

Table 3.

Alcohol-Talk Dictionary Words

| 12 pack* | Cooler | lunatic soup* | schwifty |

| 30 pack | coors | Lush | screwdriver* |

| 4 loco* | Cootie brown* | Madeira* | Semillon* |

| 4loko* | corona* | makers mark* | sex on the beach* |

| 6 pack* | cris | Malbec* | shaced |

| ABC store* | Cross buzz* | malibu | sheets to the wind |

| Absinthe | crossed | Malt liquor* | shellacked |

| absolut | crossfade* | mangled | Sherry |

| adult beverage* | crown royal | marg | Shiraz* |

| airplane bottle* | crunched | Margarita* | shit faced |

| Albarino* | crunk | margs | shitfaced |

| alc | cruzan* | Marsala wine | shitfaved |

| alcamahol* | Cuba Libre* | Martini* | shithoused |

| alch* | daquiri* | Merlot* | shmacked |

| alcohal | Dark and Storm* | michelob* | shmammered |

| Alcohol* | darty | Microbrew* | shnockered |

| alcopop* | Day drink* | miller high life* | shot glass* |

| Ale | Day drunk* | miller lite* | shots |

| Ales | DD | Miller | shwasted |

| Aligote* | dead soldier* | Milwaukee’s best* | shwasty |

| Alky | deep eddy* | mimosa* | shwaysted |

| alphabet store* | designated driver* | mini bottle* | sidewalk slammer* |

| AMF | DOCG | minor in consumption | simpler time* |

| annihilated | dos equis | Minor in Possession* | six pack* |

| aristocrat | double fist | MIP* | sixer* |

| arneis | dressed up to get messed up | mixer* | skyy |

| arsed | drink* | moellered | slap the bag* |

| Arseholed | Drinking | Mojito* | slapcup* |

| asian flush | drunchies | moonshine* | slaughtered |

| Asian glow | Drunk* | Moscato* | sliz |

| ass out | DUI* | Moscow Mule* | slizzard |

| Assed | DWI* | Müller-Thurgau* | slizzed |

| bacardi* | edward forty hands | munted | slizzerd |

| Badload | everclear* | Muscat* | sloppy |

| Baltic tea* | Faded | Natties | Sloshed |

| Bar | fifth | nattylight* | smacked |

| Barbera | figgity | natty light* | smashed |

| barcrawl* | fizzucked | natty lite* | Smirnoff* |

| barhop* | flap out | nattylite* | snookered |

| barhopping | flask* | nattys | sober* |

| barkeep | Flip Cup* | natty’s | soco* |

| Barolo | forties | natural light* | Solo Cup* |

| bars | forty | near beer* | soup sandwich* |

| bartender | four loco* | Nebbiolo* | soused |

| Bashed | funnel | never have i ever | spanked |

| battered | G and T | night cap* | spike |

| beast | G&T | OE | Spirits |

| Beaujolais | Gamay | old English* | splifficated |

| Beefeater | GandT | Old milwaukee* | spun |

| beer* | gattered | on the bottle* | Standard drink* |

| Belligerent | get a buzz | on the grog* | steaming |

| bend his elbow | get a swerve on | on the razzle* | stewed |

| bend one’s elbow | get fucked up | Ouzo* | stoli* |

| bend their elbow | get her swerve on | Pabst* | straight no chaser |

| bender her elbow | get his swerve on | Packie* | strunk |

| Bender | get iced | Paloma* | stuck like chuck* |

| Bent | get lit | partay | Stumble fuck* |

| binge drink* | get my swerve on | Partier | suds |

| black out | get schmacked | Parties | svedka* |

| Blacked | get shitty | Party | swilled |

| Blasted | get slizzard | Partying | Table wine |

| Blastered | get spun | passed out | Tall boy* |

| Blitzed | get their swerve on | patron* | tanked up |

| Bloody Mar* | Gewürztraminer | PBR* | tanked |

| Blotto | giggle juice | Petit verdot* | Tanqueray |

| bombed | giggle water | Petite Sirah* | Tecate* |

| boot and rally | gimlet* | Pickle back* | Tempranillo* |

| booted | Gin | Pickleback* | Tequila* |

| Booz* | going to boot | pickled | the mammoth |

| Bottle | got fucked up | piflicated | the spins |

| Bottles | Grenache | Pimm’s Cup* | thirty pack* |

| bourbon* | Grey Goose* | Pina Colada* | three sheets to the wind |

| Brandy | Greyhound* | pinnacle* | throw down |

| break the seal | growler* | Pinot blanc* | throw it back |

| breathal* | grown up grape juice* | pinot grigio* | throwed |

| brew | Guinness | Pinot gris* | tie one on |

| brewery | hair of the dog* | Pinot noir* | tiltered |

| brews | hammed | Pinotage* | time travel juice |

| brewski | hammered | Pint night* | tipsy |

| brown bag | hang over | Pint* | tipz |

| brown out | hangover | piss ass drunk* | Tito’s |

| browned out | hard cider* | piss drunk* | Titos |

| bubbly | hard lemonade* | pissed | toasty |

| buck chuck* | hard stuff | PJ | toddy stricken |

| bud diesel* | Hefeweizen* | plastered | toe up |

| bud heav* | Heineken* | pong | toes up |

| bud light* | hellafied | pop Cris* | Tom Collins* |

| bud lite* | hen | pop off* | too far gone |

| Budweiser* | Henny* | popov* | top shelf |

| budwieser* | high gravity | Port wine* | tor up |

| burnasties | hit the bottle* | power hour* | tore back |

| burnasty* | Hooch | pre gam* | tore up |

| burnett* | hooker | predrink* | torn down |

| busch | hosed | pregam* | toss it back |

| butt chug* | housed | Prehab* | Tossed |

| buttchug* | hung over | Prosecco* | trashcan punch |

| Buttered | hungover | pub crawl* | Trashed |

| buttery nipple* | hurricane | Quarters | Trebbiano |

| buzz* | hurt up | Rage Cage* | trnt |

| BYOB | ice luge* | rager* | True American* |

| BYOW | ice someone | Red Cup* | turn up |

| Cab franc* | in the horrors | red solo cup* | turnt |

| Cab sauv* | inebriated | retarded | twelve pack* |

| Cab Sav* | Intoxicated | ride the bus | twisted |

| Cabbaged | IPA* | Riesling* | UDI* |

| Cabernet* | Irish handcuffs | Ring of Fire | under the influence |

| Cachaça | jack daniel’s | road soda* | UV blue* |

| Caipirinha* | Jameson* | road sody | Verdicchio* |

| canned | Jim beam* | roadie* | Vodka* |

| capn* | jungle juice* | rolling rock* | Vodski |

| cap’n* | junkst | Rose all day | wacked |

| captain Morgan* | keg* | Rosé* | wankered |

| Carignan* | Keystone | Roxanne | Wasted |

| Carménère* | king cup* | Rum | Watering hole* |

| case race* | kings cup* | Saison* | wavey |

| case racing | king’s cup* | Sake* | Waxed |

| Champagne* | knob creek* | Sangiovese* | wetted |

| champers | kootered | sangria* | Whiskey* |

| Chardonnay* | krunk* | sassified | white girl wasted |

| chaser* | Lager* | sauced | wiffle beer* |

| cheeky few | lambasted | saucy | wild turk* |

| cheers to the governor | Lambrusco | Sauvignon blanc* | wine |

| Chenin blanc* | legless | sauza* | wino |

| Chianti* | liq | schmacked | wounded soldier |

| chug* | Liqour | schmammered | wrecked |

| circle of death | liquid courage | schnackered | yeungling* |

| ciroc* | Liquor | schnockered | yingling* |

| cocktail* | loaded | schnuckered | Zin |

| Cognac* | loko | schwacked | Zinfandel* |

| cold one* | lokos | schwasted | zoned |

| Colombard* | Long Island Iced Tea* | schwasty | Zonked |

Note. Asterisks indicate words that have been stemmed (i.e. any suffix that comes after this stemmed prefix will be classified as an instance of alcohol-talk).

In the third phase, we established the reliability and validity of the measure using a sample of 267 college students and over 500,000 texts messages exchanged over a 2-week period. We selected validity measures to examine how well alcohol-talk in text messages related to self-reported alcohol involvement. Prior studies show that college students report using digital communications to coordinate, facilitate, and rehash their own drinking experiences (Hebden et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2018), but they certainly also use alcohol-talk in text messages for other purposes which are unrelated to their own drinking (e.g. “Did you hear about that celebrity getting a DUI?”).

To test the validity of our alcohol-talk indices, we were particularly interested in the extent to which alcohol-talk is related to the participant’s own drinking behavior and related risks, which we examined in three ways. First, we hypothesized that alcohol-talk would fluctuate over the course of the day and week in a way that is consistent with traditional college drinking patterns (i.e. peak drinking late at night on the “drinking weekend” of Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays). Second, we expected that alcohol-talk would correlate with the student’s self-reported frequency of past year heavy episodic drinking, as well as other alcohol-related risks like whether their peers engage in alcohol or other drug use (descriptive substance use norms) and whether they think their parents and peers approve of alcohol and other drug use (injunctive substance use norms). Third, we examined whether alcohol-talk showed both between- and within-person associations with alcohol consumption, thus distinguishing not only whether students who engaged in more alcohol-talk drank more often but also whether students were more likely to drink on days when they engaged in more alcohol-talk than on other days. The text message data structure mirrors that of other forms of intensive longitudinal data (e.g., time-stamped text messages are nested within day and within-person). Intensive longitudinal data (like text messages) allow for each student to serve as his or her own control across time, permitting a test of whether deviations from one’s own baseline level of alcohol-talk are associated with within-person risk for alcohol consumption, holding all stable characteristics (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity, or socioeconomic status) constant over time (Ram, Conroy, Pincus, Hyde, & Molloy, 2012).

Methods

Participants

As part of a larger study on harmonization techniques for pooling substance use data, participants completed two lab-based visits separated by two weeks during 2015. Participants were recruited through email invitations sent to 9,000 undergraduate students at a southeastern university. Invitees were randomly sampled from all enrolled students who were aged 18–23, with oversampling for males (60%) and African Americans (14%) given their under representation in the student body. To participate in the study, students had to report alcohol use in the past year. An additional 57 people contacted us directly asking to participate, resulting in a recruitment pool of 9,057. Of these, 17% completed the pre-screen survey with 1,141 (75% of those screened before sample size targets were met) qualifying for participation. A total of 854 students completed the first visit and 840 completed both visits.

To be included in the current analysis, students had to successfully provide text message data in a second study that occurred immediately at the end of the second visit. Given a delayed start date for this protocol, 811 of the 840 participants in visit 2 were invited to be in the text study. To be eligible for the text study, participants had to have an android or iPhone with them (n=780) and consent to participate (n=531). Reasons for refusing consent included privacy concerns (19% of those invited to participate); time constraints (5%); not being motivated by the incentive, not using SMS text messaging, or primarily texting in a non-English language (1%); and disinterest/no reason (5%). As reported in Hussong and Jensen (under review), students who consented to be in the text study were similar to eligible non-consenters on demographics, mental health, and alcohol-related risk factors.

One goal of the text study was to determine feasibility of downloading two weeks of text data from students’ personal phones. An advantage of this method over providing participants with study phones is that the text messages we captured were not subject to non-reporting or self-censoring biases (e.g., changes in texting behavior as a result of being in a study). However, our method did require many adjustments in software platform as iOS and other updates rolled out over the course of data collection (see Hussong & Jensen, Under Review). As a result, text data downloads were sometimes not successful, resulting in a 50% capture rate and 267 participants contributing text data to the current analysis. On average, these participants sent 932 texts and received 1294 texts over the 2-week study period (for a cumulative 569,172 texts sent and received over the study period). The resulting text dataset is thus intensive longitudinal data. It contains 569,172 text messages nested within 3738 days (14 days per person), nested within 267 students.

The text message sample comprised 267 college students (mean age= 19.87; 40.8% male; 56.82% White, 21.97% Black, 7.58% Asian, .38% American Indian, 6.44% two or more races; 7.58% Hispanic of any race); students in the text sample did not differ from the rest of the sample (without text data) on any of these demographic indices except that they were less likely to be male (χ2(1)=4.12, p=.046) and Asian (χ2(1)=5.71, p=.02). The text sample was comparable to the rest of the sample on past year alcohol use frequency, quantity, and frequency of heavy alcohol use. In addition, the text sample was highly comparable to the undergraduate student body from which the sample was drawn on all demographic indicators, though more ethnically diverse (by design) and less evenly distributed across matriculation status (see Hussong & Jensen, Under Review for evidence of representativeness of the sample and text messages).

Measures

All survey measures of student alcohol use and related risks were assessed at visit 1. Past year Heavy Episodic Drinking (HED) frequency was assessed in a single item at visit 1 which asked students to rate how many times in the past year they drank more than five consecutive drinks on any single occasion (Johnston et al., 2011a), using a response scale which ranged from 0 (‘0 occasions’) to 6 (‘40 or more occasions’; M=2.54, SD=1.90).

Students’ perceptions of whether their peers drink or do drugs (descriptive norms) and their perceptions of whether friends and family approve of substance use (injunctive norms) are well-established risk factors for one’s own drinking (Borsari & Carey, 2001). Peer descriptive substance use norms assessed participants’ perceptions of their peers’ substance use behaviors, using nine items adapted from the Monitoring the Future study (Johnston et al., 2011b). Participants responded to separate items about each class of substance use concerning how many of their friends drink alcohol, get drunk regularly, smoke cigarettes, use e-cigarettes or vape, use other types of tobacco, use marijuana, take unprescribed Ritalin, take unprescribed opiates, or use other types of drugs. Participants responded using a five-point response scale (0=none to 4=all). A mean of these items formed the peer descriptive norms scale for the current study (M=1.34; SD=.55; alpha=.83).

Items for injunctive substance use norms assessed attitudes of close friends and parents (separately) toward substance use by the respondent, with separate questions for each of the same nine classes of substance use. The scale was again adapted from the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston et al, 2011b) and participants responded using a 5-point response scale (ranging from 1=strongly approve to 5=strongly disapprove). A mean of these items formed the peer (M=2.07; SD=.70; alpha=.87) and parent (M=1.47; SD=.39; alpha=.77) norms scales for the current study.

At visit 2, students completed an adapted two-week timeline follow-back procedure (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) to assess daily alcohol use (0=no, 1=yes) for the past 10 days. Participants were given access to a past two-week events calendar (with relevant events like basketball games and holidays) as well as to their mobile phones to access their personal calendars to use as memory aids. In total, 9 students are excluded from daily alcohol use analyses due to not completing the timeline follow-back procedure. Students reported drinking on an average of 1.8 days over the 10 day follow back procedure (SD= 1.8); 72 students never reported drinking over this period (27.9% of sample).

Text message-derived measures.

We used the LIWC program to quantify the number of alcohol-talk words in each text message. LIWC automatically calculates count data as a percentage of words, in this case, alcohol-talk words, per text message. We converted the per message percentage of alcohol-talk to a total word count per text message to facilitate interpretation. We then computed daily alcohol-talk by summing the total number of alcohol-talk words that each participant exchanged over the day. Likewise, total daily word count was computed by summing all the words each participant exchanged over the day. Notably, for multilevel models of daily associations with daily alcohol use, 4 am was used as the cutoff for the day (rather than midnight), to more closely align with student bedtimes (as evident in shard declines in texting behavior) and student-report of daily alcohol use on the timeline follow-back procedure (e.g. if a student reported drinking on Friday in their time line follow back, they likely counted the early morning hours of Saturday, such as after midnight but before they went to bed, as Friday drinking rather than Saturday drinking). We then calculated the mean number of daily alcohol-talk words (separately for sent and received) for each person, comprising person-means for inclusion in multilevel models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

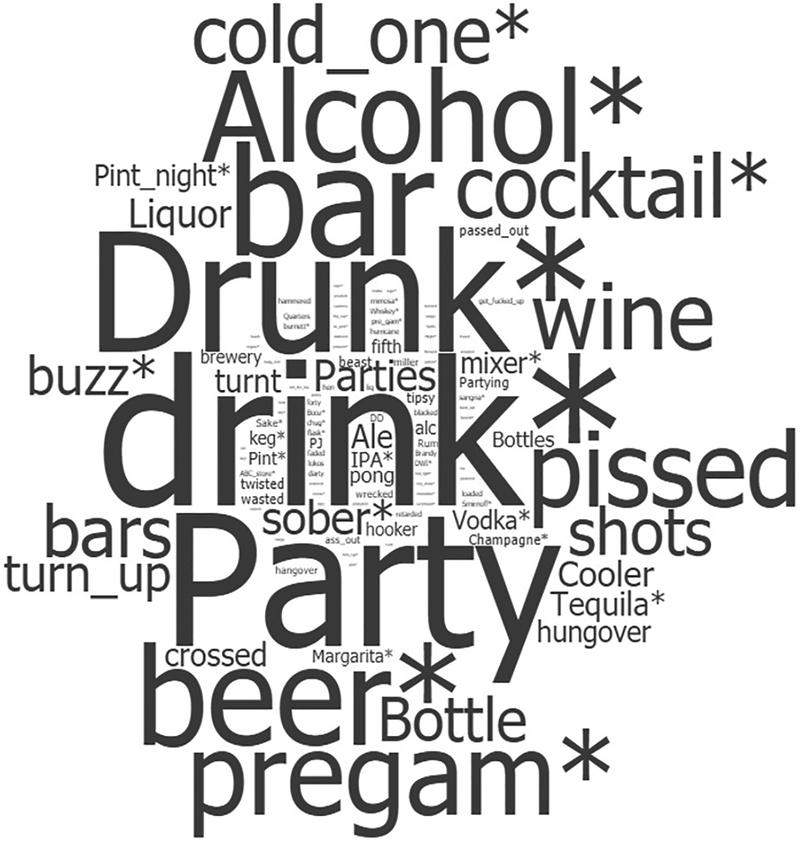

Base rates of alcohol-talk are depicted in Figure 1. Of the 524 alcohol-talk words, 200 occurred at least once during the two-week observation period and 326 words never occurred. Not surprisingly, alcohol-talk represented a tiny proportion of all college student text interactions. The average student exchanged a total of 50 alcohol-talk words over the two-week study period (SD=52.7; range 0–355; meansent= 20.7, SDsent=24.0; meanreceived=29.2, SDreceived=31.1) and less than 1/3 of 1% of all words texted were alcohol-talk words (.30% of words texted; SD=.49%). However, most students participated in alcohol-talk at some point over the study period, with only 6 students never exchanging any alcohol-talk (2.25% of sample).

Figure 1. Most commonly used words in the alcohol-talk dictionary.

Note. Larger word size indicates higher relative frequency of use

Reliability

Following established procedures for psychometric evaluation in dictionary development (Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015), the alcohol-talk dictionary was separated into its 524 constituent words, and each word counted and measured as a percentage of words in each of the 267 corpora of college student text messages. Each word was treated as a “response/item” in computing Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency. Acceptable alphas are often much lower in dictionary development than in traditional self-report research (Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015), but nonetheless we would expect that greater engagement in alcohol-talk should increase use of all words in the dictionary. The Cronbach’s alpha for alcohol-talk was .64, reflecting good internal consistency for a language dictionary given that it is as high or higher than commonly used native LIWC dictionaries for such constructs as positive emotion words (620 words; α=.23), negative emotion words (744 words; α=.17), sexual words (131 words; α=.37), ingestion words (184 words; α= .67), and swear words (131 words; α=.45; Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015). Potential changes to the alpha coefficient were also calculated if each word were to be deleted; word deletion had no substantial effect on the alpha.

Validity

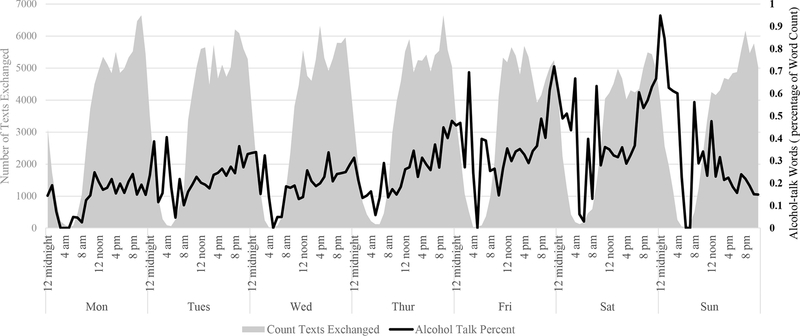

Figure 2 depicts how text messages and alcohol-talk fluctuate over the course of a day across the entire week in sample of over a half million text messages. Alcohol-talk percentage scores tended to peak in the late night/early morning hours over the Thursday-Saturday “drinking weekend”. These spikes in alcohol-talk also tended to overlap with steep decreases in the total number of texts exchanged (grey area plotted on the left y-axis); that is, much of the sample is likely going to sleep (and not texting) but among those texts that are exchanged during these late night/early morning hours, a greater proportion are likely to be alcohol-talk.

Figure 2. Number of Texts and Alcohol Talk by Hour of Day and Day of Week.

Note. Plot of alcohol talk in all text messages over the study period (569,172 text message observations across 267 participants). The dark black line (with values on the right axis) depicts alcohol-talk as a percentage of words exchanged by hour. The grey region (with values on the left axis) depicts the total number of texts exchanged by hour.

As shown in Table 1, between-person correlations demonstrate that alcohol-talk, measured as the percentage of words in each person’s sent and received text messages, correlates significantly with perceptions of parent injunctive substance use norms and self-report of past year frequency of binge drinking. Furthermore, alcohol-talk in received text messages is significantly correlated with peer descriptive and injunctive substance use norms.

Table 1.

Between-Person Correlations Between Alcohol-talk, Norms, and Drinking

| Peer Descriptive Substance Use Norms | Peer Injunctive Substance Use Norms | Parent Injunctive Substance Use Norms | Past Year Heavy Episodic Drinking Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol-talk (Sent) | .10 | .09 | .13* | .20*** |

| Alcohol-talk (Received) | .15* | .18** | .16** | .25*** |

Note. N=267 students.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05

As shown in Table 2, high alcohol-talk days were more likely to be drinking days; each alcohol-talk word was associated with a 22–23% increase in likelihood of drinking that day after controlling for overall word counts. Between-person effects showed that higher average levels of alcohol-talk across all days were also associated with a higher percentage of drinking days (over and above the daily linkages), such that a one word increase in average daily sent alcohol-talk is associated with a 14% increase in the number of drinking days (ORsent=1.14, p=.021), though no such relation with average received alcohol-talk emerged.

Table 2.

Multilevel Models of Alcohol-Talk Predicting Any Daily Alcohol Use

| Any Daily Alcohol Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | CI | OR | p | |

| Daily β1 | .21 (.02) | .16, .26 | 1.23 | <.0001 |

| Person-mean slope γ01 | .13 (.07) | .001, .26 | 1.14 | .048 |

| Alcohol-talk (Received) | ||||

| Daily β1 | .20 (.02) | .16, .25 | 1.22 | <.0001 |

| Person-mean slope γ01 | .06 (.05) | −.04, .16 | 1.06 | .22 |

Note. 10 days of data across 258 students yielded 2575 daily observations (one student was missing 5 days of Timeline Follow Back data).

DISCUSSION

Alcohol-talk shows considerable promise as a measurable construct of interest within computer-mediated communication and a significant predictor of both within- and between-person risk for engaging in self-reported drinking behaviors. The developmental process behind the dictionary demonstrates the many ways in which college students refer to alcohol and the coherence of alcohol-talk as a thread of communication that is now easily identifiable within text-communication. The ubiquity of text communication within the high-risk drinking environment of college students raises exciting future directions for prevention research regarding the construct of alcohol-talk specifically and the utility of such dictionary-based approaches to coding high intensity data more broadly.

Our 524-term alcohol-talk dictionary is rather comprehensive, though we recognize the potential importance of local referents that may be needed in different locations. The challenge of creating an alcohol-talk dictionary, as opposed to a measure of other constructs, is in part due to the colorful and indirect words that college students use to refer to drinking and its correlates. We are not the first to make this observation. Most notably, a 1773 article in the Pennsylvania Gazette attributed to Benjamin Franklin, entitled “The Drinker’s Dictionary”, recognizes 228 synonyms for drunkenness and observes that:

“But Drunkenness […] is therefore reduc’d to the wretched Necessity of being express’d by distant round-about Phrases, and of perpetually varying those Phrases, as often as they come to be well understood to signify plainly that a Man is drunk.[…] Tho’ every one may possibly recollect a Dozen at least of the Expressions us’d on this Occasion, yet I think no one who has not much frequented Taverns would imagine the number of them so great as it really is.”

Despite the variety of words included in the alcohol-talk dictionary, we found evidence of acceptable internal consistency suggesting reliability in assessing a core construct. Furthermore, the dictionary demonstrated validity in tapping alcohol-related risk. Alcohol-talk percentage scores were highest during those hours when we expect the most college student drinking (late night-early morning on Thursday-Saturday). Moreover, more frequent alcohol-talk was related to more frequent heavy episodic drinking; more frequent received (but not sent) alcohol-talk was related to stronger peer descriptive and injunctive substance use norms; and more frequent sent and received alcohol-talk was related to strong parent injunctive substance use norms. These findings suggest that although alcohol-talk is not the same as alcohol use (as evidenced by the significant but modest correlations), alcohol-talk is a clear marker of alcohol involvement that correlates in expected ways with parent and peer substance use norms in a manner parallel to that for self-reported alcohol use (e.g. LaBrie et al., 2010; Varvil-Weld et al., 2014). Indeed, specificity in received and not sent alcohol-talk messages with peer norms is further evidence that these dimensions of alcohol-talk align in expected ways with peer versus self-referent correlates.

Our analysis of daily associations between alcohol-talk and daily drinking further confirmed that alcohol-talk is a valid predictor of drinking behavior that may have useful prevention implications. Most strikingly, alcohol-talk is strongly predictive of not only who is at risk for greater drinking among college students but also when that drinking is likely to occur. People who sent more alcohol-talk words during the observation period reported more frequent drinking (over and above the daily associations); this was not true of alcohol-talk in received texts, confirming an expected specificity in whose alcohol-talk is more closely aligned with daily drinking. On days when individuals increase their own alcohol-talk, risk for drinking also rises. This risk is notable as each alcohol-talk word a person sends is associated with a 23% higher chance of drinking that day, and each alcohol-talk word received associated with a 22% higher chance of drinking that day.

Taken together, these results suggest that the alcohol-talk dictionary is a valid, useful tool for identifying alcohol-related language in college student text messages, and we are likely only scratching the surface of the promise of this tool. The alcohol-talk dictionary is a time saver; analysis that would have previously monopolized hundreds of coder hours spent meticulously combing through digital communications for the presence of alcohol-related content can now be conducted with the push of a button. The alcohol-talk dictionary can also be used as a pre-processor to flag alcohol-related content for more nuanced qualitative coding by hand. Furthermore, the alcohol-talk dictionary allows researchers access to data on alcohol involvement that is not subject to the biases inherent in self-report. For instance, alcohol-talk by one’s peer network could serve as a useful as an indicator of peer network norms or contextual risk. This approach is particularly important for theoretically-driven research (versus data-driven machine learning approaches), possible to conduct with smaller samples of people and texts, and a replicable tool whose findings are not sample dependent (versus other data clustering approaches).

These results also suggest potential applications for prevention of problematic alcohol use. First, the alcohol-talk tool may be used in prevention as an alternative to self-report measures in identifying who is more heavily immersed in an alcohol-rich digital environment and at risk for heavier alcohol involvement. With student consent, clinicians or other prevention scientists can apply the alcohol-talk dictionary to text messages or more widely available social media content and use it as a latent indicator of immersion in an alcohol-rich environment. This information could in turn be used to target specific students for prevention programs or messaging. Moreover, this tool can be applied in such a way that text-based interactions are digitally reviewed, and the alcohol-talk index provided to the prevention scientist without revealing the content of any individual text. Second the alcohol-talk tool may be used to identify when alcohol involvement is highest (i.e. when during the day, week, year), and thus target prevention programs to these time frames. In theory, this could be implemented on a macro scale (i.e. helping a university identify times of year that are characterized by more alcohol-talk and thus alcohol involvement, and implement programming accordingly) or a micro scale (i.e., within-individual, helping a clinician and client track alcohol-talk as an indicator for risky use). In its current state, application of the alcohol-talk dictionary to macro processes seems appropriate, but extension to within-individual, dynamic, micro processes (e.g. momentary interventions) requires more research and development.

Despite these strengths, we are aware of potential limitations and areas for future development. First, the alcohol-talk dictionary has been validated at a single location. It is entirely possible that the language used to talk about drinking among college students at our southern university in 2017 is different than that used by younger teenagers, or older adults, or residents of the Pacific Northwest, or in Reddit posts, or even in text messages from 2005. However, the alcohol-talk dictionary could and should be updated to incorporate linguistic differences and evolutions and future research is needed to test the utility of this tool with public and private text corpora (e.g. Twitter, Facebook posts, blogs) as well as samples from different geographical regions, developmental periods, and historical times. Second, the alcohol-talk dictionary casts a wide net to capture many different types of alcohol-related content like drinking locations (e.g. “bars”), drinking games (e.g. “flip cup”), words to describe intoxication (e.g. “hammered”), and alcohol-related consequences (e.g. “DUI”). Some types of alcohol-talk likely occur before drinking occurs (e.g. coordinating drinking opportunities) whereas others may be more common during or after a drinking episode (e.g. texting about current intoxication or rehashing last night’s festivities). Future research should examine sub-categories of alcohol-talk, with attention to those dimensions which may have differential prediction for alcohol-related misuse and related health risks. For example, Levitt and colleagues (Levitt et al., 2009) used factor analysis to show that their list of commonly used words to indicate intoxication loaded onto two factors which reflected moderate or heavy intoxication. Future research should also attend to the temporal relations between alcohol-talk and alcohol use to better establish whether certain types of alcohol-talk are more likely to precede use and thus more salient indictors for when prevention messages might be delivered. Third, though we present here initial evidence of reliability and validity of the alcohol-talk dictionary, we note that, like all lexicon coding tools applied to brief texts, homophones for words in the dictionary (e.g. “wasted”, “blasted”, and “smashed”) are likely being mis-identified as instances of alcohol-talk. Future research should utilize labeled data to quantify the proportions of hits, misses, and false alarms and used to refine the alcohol-talk dictionary.

These limitations notwithstanding, we believe that the alcohol-talk dictionary is useful tool for researchers who seek to better understand the social ecologies of alcohol use and misuse, and in related prevention efforts. A large part of human interaction today occurs via computer mediated text-based communication, and analysis of the digital traces left behind by these conversations hold significant promise for social science’s understanding of the role of social relationships in the development of patterns of alcohol use and associated risks.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R01DA034636–01A1, and by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376) through the Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to Michaeline Jensen. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research Journal Of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EE, & Wojcik SP (2016). A practical guide to big data research in psychology Psychological Methods, 21(4), 458–474. US: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/met0000111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier AK, & Clarke SW (2011). Do college students use Facebook to communicate about alcohol? An analysis of student profile pages. Cyberpsychology, 5(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hebden R, Lyons AC, Goodwin I, & McCreanor T (2015). “When You Add Alcohol, It Gets That Much Better”: University Students, Alcohol Consumption, and Online Drinking Cultures Journal Of Drug Issues, 45(2), 214–226. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA. doi: 10.1177/0022042615575375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, Hussong AM, & Baik J (2018). Text Messaging and Social Network Site Use to Facilitate Alcohol Involvement: Comparison of US and Korean College Students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking, 21(5). doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2011a). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010. Volume II, College Students & Adults Ages 19–50 Institute For Social Research(Vol. I). ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2011b). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50 Institute For Social Research, I. Ann Arbor, MI: ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Kern ML, Park G, Eichstaedt JC, Schwartz HA, Sap M, Smith LK, & Ungar LH (2016). Gaining insights from social media language: Methodologies and challenges Psychological Methods, 21(4), 507 US: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/met0000091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M, Wang Y, Lakkaraju H, & Leskovec J (2016). Mining big data to extract patterns and predict real-life outcomes. Psychological Methods, 21(4), 493–506. doi: 10.1037/met0000105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, & Larimer ME (2010). Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 343–349. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Sher KJ, & Bartholow BD (2009). The language of intoxication: Preliminary investigations. Alcoholism: Clinical And Experimental Research, 33(3), 448–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00855.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR (2006). Quantitative Text Analysis Handbook Of Multimethod Measurement In Psychology (pp. 141–156). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11383-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, & Whitehill JM (2014). Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 36(1), 91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Boyd RL, Jordan K, & Blackburn K (2015). The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015. UT Faculty/Researcher Works. Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin. doi: 10.15781/T29G6Z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2018a). Mobile Fact Sheet.

- Pew Research Center. (2018b). Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet.

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline Followback: A Technique for Assessing Self Reported Ethanol Consumption. Vol. 17 Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (Vol. Series H-4). [Google Scholar]

- Varvil-Weld L, Crowley DM, Turrisi R, Greenberg MT, & Mallett K. a. (2014). Hurting, Helping, or Neutral? The Effects of Parental Permissiveness Toward Adolescent Drinking on College Student Alcohol Use and Problems Prevention Science, 15(5), 716–724. Springer. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0430-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgate EC, Neighbors C, Heppner H, Jahn S, & Lindgren KP (2014). “I will take a shot for every ‘like’I get on this status”: Posting alcohol-related Facebook content is linked to drinking outcomes Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs, 75(3), 390–398. Rutgers University. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, & Hingson R (2013). The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 35(2), 201–18. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]