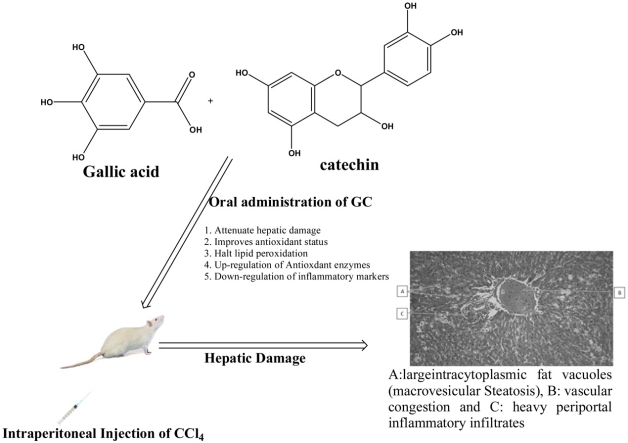

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ARE, antioxidant response element; AST, aspartate transaminase; CAT, catalase; cDNA, complementary deoxyribonucleic acid; DGA, dodecylgallate; GA, gallic acid; GAPDH, glyceraldehydes3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; GSH, glutathione; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; IL-1β, interleukin 1beta; IL-6, interleukin 6; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; Keap1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; MDA, maloniadehyde; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells; Nrf 2, nuclear factor erythroid- derived 2 like 2 genes; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SYBR, green fluorescent DNA Stain; TB, total bilirubin; TP, total protein; TNF α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Keywords: Gallic acid, Antioxidant, Liver disease, Anti-inflammatory, Cytokines

Highlights

-

•

Attenuate hepatic damage.

-

•

Improves antioxidant status.

-

•

Inhibits lipid peroxidation.

-

•

Possess anti-inflammatory properties.

Abstract

Gallic acid (GA) is a known phenolic compound with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-cancer activities. The objective of this research is to evaluate the preventive role of GA against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) induced liver fibrosis. Thirty-five (35) male Wistar rats were used in this study and were equally distributed into five groups (7 rats each). All groups were acclimatized for a week, Group I (control) rats were administered distilled water only. Group II rats were induced with a single dose of CCl4 (1.25 mL/kg in olive oil (1:1); IP) to cause hepatic damage, while Groups III, IV, and V, rats were intoxicated with CCl4. After 24 h the rats in groups III, IV, and V were given 50 mg/kg of silymarin, 50 mg/kg of GA, and 100 mg/kg of GA daily for one week respectively. Rats were sacrificed and fasting blood was estimated for biochemical analysis while the liver was excised for molecular studies. Results from this study revealed that GA significantly decreases serum hepatic enzymes, down-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin 1 beta (IL-1B), interleukin 6 (IL-6), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX 2), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF α), and up-regulate antioxidant gene expression (superoxide dismutase and catalase). The use of gallic acid as natural antioxidants can be promising in ameliorating liver diseases.

1. Introduction

The liver is an essential organ involved in more than five hundred metabolic reactions in the biological system and one of its major functions is the detoxification of poison or harmful substances, but can also be injured by the toxicants, which in the process may distort the metabolic activities of the liver, leading to acute liver failure [1]. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a hepatotoxin, which causes liver necrosis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis when injected or orally given to experimental animals [2,3]. Although the mode of action of CCl4 induced hepatic injury is hydra-headed, but there is a piece of evidence that several mediators of inflammation and oxidative stress may play a role in the pathophysiology of CCl4 induced hepatic damage. The inflammatory initiators responsible for liver injuries are IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS, and COX-2 [4].

The crosstalk linking Nrf2 and NF-κB is implicated in hepatic injury. Nrf2 is a transcription factor involved in the enhancement of the cellular defense system to halt oxidative damage and inflammation. It induces the expression of antioxidant target genes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione, and heme oxygenase 1, and in the process hinders the activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB thereby preventing the transcription of pro-inflammatory mediator [[5], [6], [7]]. Nrf2 is found in association with a protein called kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), which keeps Nrf2 from undergoing degradation. Under the condition of oxidative stress, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1 protein in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus which then binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) located within the promoter region of specific target genes where it triggers the expression of cytoprotective enzymes [[8], [9], [10]]. Previous studies revealed that the interference between Nrf2 and Keap1 interactions can lead to the stabilization and nuclear translocation of Nrf2 [11]. Therefore, molecules that can competitively inhibit Keap1 from binding to the Nrf2 site would provide an alternative pathway for the activation of Nrf2. The pharmacological stimulation of Nrf2 is a promising medicinal target by GA for the treatment and prevention of hepatic damage associated with oxidative stress and inflammation.

The liver is prone to several pathologies, because of its incessant exposure to an environmental toxin, drug abuse, chronic alcohol intake, viral infections, and autoimmune diseases [12]. Despite remarkable improvements in modern medicine, the management of liver diseases is challenging. Currently, the search for alternative and complementary medicines with antioxidant properties has become the point of focus in the management of liver problems. Now there is an increasing interest in phytoconstituents, especially phenolic compounds, due to their beneficial effects on disease prevention and longevity [13].

Gallic acid is a secondary metabolite with a phenolic ring (Fig. 1) that is found in grapes, oak bark, green tea, apple peels, strawberries, pineapples, banana, and lemon [14]. Gallic acid and its derivatives possess numerous biological activities such as antiviral, antifungal, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [15]. Therefore, the treatment of liver fibrosis by GA could be linked to the down-regulation of inflammatory responses mediated by cytokines and the up-regulation of antioxidant genes [16]. The purpose of this research project is to investigate the hepatoprotective, anti-oxidative, and anti-inflammatory activities of gallic acid in CCl4 induced hepatic damage in Wistar rats.

Fig. 1.

Structure of gallic acid.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All substances were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated. The test substances were dissolved in distilled water and prepared fresh daily for administration to the animals

2.2. Animals

Eight weeks old Wistar rats, weighing between 150−170 g, bred in the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin was used for the research. They were kept in clean cages in a 12 h light/dark cycle with litter changed daily. The animals were housed in galvanized rat cages and acclimatized on rat chow. Animal experimentation followed strictly the care and use of animals [17] and was approved by the local University Ethics Committee for Animal Research with approval number LS20014

2.3. Experimental protocol

Thirty-five male Wistar rats were used in this study and were distributed equally into five groups (7 rats each). All groups were acclimatized for a week, Group I rats which serve as control was given distilled water only, Group II rats were induced with single-dose CCl4 (1.25 mL/kg in olive oil (1:1); IP) to cause hepatic damage, while Groups III, IV, and V, rats were intoxicated with CCl4 (1.25 mL/kg, in olive oil (1:1); IP) and after 24 h the rats in group III were given 50 mg/kg of silymarin daily for 7 days, while groups IV and V were given 50 and 100 mg/kg of GA daily for one week respectively. On the 8thday, blood samples were collected from overnight fasted rats via decapitation and the serum was separated for biochemical analysis, while the liver was excised for antioxidant and molecular studies.

3. Biochemical analysis

3.1. Determination of hepatic enzymes

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined using the method of Reitman and Frankel [18]. For the determination of ALT activity, the serum sample was added to the buffered solution containing DL-alanine and α-ketoglutarate (pH 7.4) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation 1.0 mM, DNPH was added, followed by the addition of 0.4 M NaOH and absorbance read at 500 nm, while AST activity; the serum sample was added to the buffered solution containing L-aspartic and α-ketoglutarate (pH 7.4) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation 1.0 mM, DNPH was added, followed by the addition of 0.4 M NaOH and absorbance read at 500 nm.

ALP activity was determined using a Teco kit and method described by Kochmar and Moss, [19]. Precisely 0.5 mL of alkaline phosphatase substrate was placed into test tubes and equilibrated for 3 min at 37 °C. At the timed interval, 0.05 mL for each standard, control, and the sample was added to their respective test tubes, mix gently and incubate for 10 min. at 37 °C. Alkaline phosphatase color developer (2.5 mL) was added to the respective test tubes and absorbance read at 590 nm

Determination of GGT activity [20] the serum sample was added to a substrate solution containing glycylglycine, MgCl2, and γ-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide in 0.05 M Tris (free base) pH 8.2. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 min and absorbance read at 405 nm at 1 min interval for 5 min. The activity of GGT was calculated from the absorbance value using the formula.

3.2. Determination of plasma proteins and bilirubin

Albumin and Total protein were evaluated using standard Radox kit and described by Tietz [21], while Total bilirubin was determined using Radox kit and the method described by Jendrassik and Grof [22]

3.3. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

The level of SOD activity was determined according to the method of Misra and Fridovich, [23]. The liver fraction was reacted with epinephrine solution and the rate of inhibition of adrenochrome solution from the autooxidation of epinephrine was measured spectrophotometrically at 480 nm.

3.4. Catalase activity

Catalase activity in the liver was determined as previously described by Asru [24]. The liver fraction was added to 0.2 M H2O2 solution and samples of this mixture were withdrawn at various intervals into a dichromate/acetic acid buffered solution. The rate of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide was determined spectrophotometrically at 480 nm.

3.5. Reduced glutathione

The determination of reduced glutathione (GSH) level of tissue was based on the measurement of the absorbance of 2 nitro 5-thiobenzoic acid formed, at 412 nm [25], when Ellman’s reagent reacted with GSH. An aliquot of the liver fraction was deproteinized in 4% sulphosalicylic acid and centrifuged at 17,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was reacted with Ellman’s reagent and the absorbance of the complex formed read at 412 nm. The amount of GSH in the liver fraction was determined from a standard GSH calibration curve.

3.6. Determination of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was assessed in terms of malondialdehyde (MDA) formation in the rat liver and was performed as described previously by Beuge and Aust [26]. Precisely 1 mL of homogenate was added to 2 mL of TCA-TBA-HCL reagent followed by thorough mixing by swirling. The resulting solution was heated for 15 min in a boiling water bath. The flocculent precipitate, after cooling, was removed via centrifugation at 10,000 revolutions for 10 min. The absorbance of the clear supernatant was taken at 535 nm against a reference blank.

4. Molecular studies

4.1. Gene expression by RT-PCR

The gene expression by RT-PCR is described by placing the liver samples in RNA later inside the Eppendoff tube for RNA analysis. Three hours later, cells were collected and total RNA extracted using Trizol (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were quantified with the NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using oligo (dT) primers (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Real-time quantitative PCR amplification and detection were performed on optical-grade 48-well plates in an Eco Real-Time PCR System (Illumina, CA, USA) with 20 ng of cDNA, the SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA), and specific primers at their annealing temperature (Table 1). To normalize mRNA expression, the expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehydes3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was measured for comparative reference. The mRNA relative quantitation was calculated using the ΔΔCT method

Table 1.

Primer sequences the genes used for real-time RT-PCR.

| Gene | Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β primers | Forward | 5’-CCTTCCAGGATGAGGACATGA 3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-TGAGTCACAGAGGATGGGCTC-3’ | |

| IL-6 primers | Forward | 5’-GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA-3’ | |

| COX-2 primers | Forward | 5’-CAGACAACATAAACTGCGCCTT-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-GATACACCTCTCCACCAATGACC-3’ | |

| TNF α primers | Forward | 5’-TCAGCCGATTTGCTATCTCATA-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-AGTACTTGGGCAGATTGACCTC-3’ | |

| CAT | Forward | 5’-GAGGCAGTGTACTGCAAGTTCC-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-GGGACAGTTCACAGGTATCTGC-3’ | |

| SOD | Forward | 5-'GCAGAAGGCAAGCGGTGAAC-3' 5’- |

| Reverse | TAGCAGGACAGCAGATGAGT-3’ | |

| GAPDH | Forward | 5’-CCCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGC-3’ |

| Reserve | 5’-CCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAGC-3’ | |

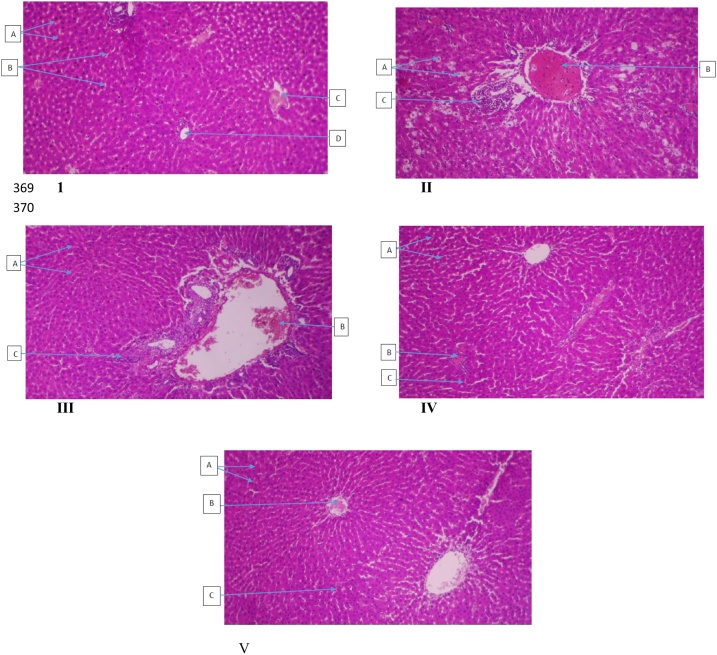

5. Histological analysis

Histological analysis was done according to the method described by Kumar et al. [27]. The liver samples were processed distinctly for histological observation. The sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined microscopically for histopathological changes. The histopathological slide was read by an expert in histology.

6. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M using SPSS 26 software. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way analysis of variance by multiple comparisons. Differences between means were estimated by Duncan’s multiple range tests and a value of p < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant

7. Results

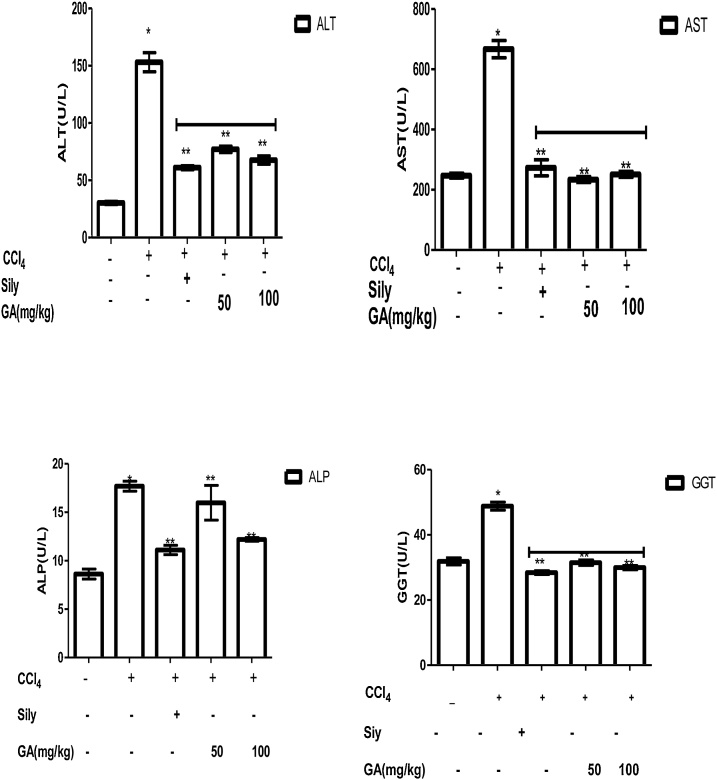

7.1. Hepatoprotective potential of gallic acid on hepatic enzymes in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats

The inhibitory effect of GA on serum hepatic enzymes in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats are shown in Fig. 2. It was observed that rats injected with CCl4 intraperitoneally caused a significant increase (p < 0.05) in ALT, AST, ALP and GGT activities by 80.00 %, 62.94 %, 51.27 %, and 34.71 % respectively when compared with rats in group 1. However, administration of GA (50 mg/kg body weight) to the rats for 7 days after injecting rats with CCl4 protected the liver by 53.63 % for ALT, 64.92 % for AST, 9.6 % for ALP, and 35.59 % for GGT when compared to rats induced with CCl4 only (Group II). Similarly, treatment of the rats with 100 mg/kg of GA for 7 days after the administration of CCl4 protected the liver from damage with ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT having percentage protection of 55.85 %, 62.32 %, 31.03 %, and 38.61 % respectively. Also, treatment of group III rats with standard drug, silymarin (50 mg/kg) for 7 days protected the liver from damage with ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT having percentage protection of 60.1 %, 59.0 %, 37.19 %, and 41.8 % respectively when compared to group II rats.

Fig. 2.

Hepatoprotective potential of gallic acid on hepatic enzymes in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 7. * The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to the control; **The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to CCl4.

7.2. Hepatoprotective potential of gallic acid on albumin, bilirubin and total protein concentration in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats

The hepatoprotective effect of gallic acid on some biomolecules in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats is shown in Table 2. Results show that there was a significant increase in albumin concentration in rats intoxicated with CCl4 when compared to control rats. However treatment with GA at a dose of 100 mg/kg significantly reduces albumin concentration when compared to group II, but at a lower dose of GA (50 mg/kg), there was a significant increase in albumin concentration when compared to group II rats. Also, there was a non-significant increase in total protein concentration in rats intoxicated with CCl4 when compared to control, but treatment with GA at doses of 50 and 100 mg/kg body weight significantly increases total protein concentration in a dose-dependent manner when compared to group II rats.

Table 2.

Hepatoprotective potential of gallic acid on albumin, bilirubin and total protein concentration in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats.

| Groups/Treatment | Total Prot.(g/dl) | Bilirubin(mg/dl) | Albumin(g/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 2.31 ± 0.05a | 0.52 ± 0.04a | 0.44 ± 0.08a |

| Control | |||

| Group II | 2.45 ± 0.13a | 0.74 ± 0.02b | 1.15 ± 0.21b |

| CCl4 only | |||

| Group III | 3.98 ± 0.19b | 0.58 ± 0.06c | 0.75 ± 0.07c |

| CCl4+Sil(50 mg/kg) | |||

| Group IV | 2.33 ± 0.29a | 0.66 ± 0.06c | 1.33 ± 0.54c |

| CCl4+GA(50 mg/kg) | |||

| Group V | 2.84 ± 0.17a | 0.51 ± 0.12c | 0.90 ± 0.15c |

| CCl4+GA(100 mg/kg) |

Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 7. Values with different alphabets are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Consequently, it was observed that gallic acid at both doses (50 and 100 mg/kg respectively) significantly reduce the increased concentration of bilirubin caused by CCl4 insult. There was also a significant rise in total protein and albumin concentrations in rats administered with silymarin (50 mg/kg) and a significant decrease in serum bilirubin concentration.

7.3. Inhibitory cause of gallic acid on malondialdehyde levels in CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity in rats

The inhibitory cause of gallic acid on liver malondialdehyde levels as a marker of lipid peroxidation in CCl4 induced liver damage is shown in Table 3. The result shows that there was a significant increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in rats given CCl4 when compared to the control. However, treatment with 100 mg/kg of gallic acid significantly reduce MDA levels compared to rats induced with CCl4 only, but showed a non-significant difference in rats administered the lower dose of gallic acid. Similarly, treatment of group III rats with the standard hepatoprotective drug, silymarin, caused a significant reduction in the MDA level compared to group II rats (CCl4 only).

Table 3.

Inhibitory effect of gallic acid on malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

| Groups/Treatment | MDA(nmol/g tissue) X 10−3 |

|---|---|

| Group I Control |

1.81 ± 0.01 |

| Group II CCl4 only |

3.71 ± 0.11a |

| Group III CCl4 + Sily(50 mg/kg) |

1.15 ± 0.02b |

| Group IV CCl4 + GA (50 mg/kg) |

3.16 ± 0.84a |

| Group V CCl4 + GA (100 mg/kg) |

2.58 ± 0.05b |

Values are Mean ± SEM, n = 7 rats in each group. Values with different alphabets are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

7.4. The stimulating effect of gallic acid on antioxidant status in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats

The effect of gallic acid on antioxidant status in CCl4 induced liver damage in Wistar rats is shown in Table 4. Findings from this study showed that there was a significant decrease in superoxide dismutase (0.67 U/mg protein) and catalase (0.45 μmolH2O2 consumed/min/mg prot) activities in rats given CCl4 only when compared to the control. Treatment of oxidatively stressed rats with gallic acid significantly increase SOD (1.05 U/mg protein) and CAT (0.75 μmolH2O2 consumed/min/mg prot)) activities in a dose-dependent manner. It was also observed that rats intoxicated with CCl4 resulted in the depletion of GSH compared to rats in the control group (p < 0.05; Table 4). Interestingly, a significant increase in GSH content was observed after post-treatment with gallic acid in a dose-dependent manner for 7 days. Similarly, silymarin caused a significant improvement in the oxidative status of the rats with values of 1.13 U/mg protein for SOD, 0.79 μmolH2O2 consumed/min/mg prot for CAT, and 5.64 μmol/g protein for GSH when compared to rats induced with CCl4 only. These data reveal that gallic acid alleviated liver oxidative injuries.

Table 4.

Inhibitory effect of gallic acid on superoxide dismutase and catalase activities in CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

| Groups/Treatment | SOD (Units/mg prot.) | CAT(μmolH2O2 consumed/min/mg prot.) | GSH (μmol/g prot.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 2.00 ± 0.001 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 6.42 ± 0.21 |

| Control | |||

| Group II | 0.67 ± 0.001a | 0.45 ± 0.01a | 2.81 ± 0.14a |

| CCl4 only | |||

| Group III | 1.13 ± 0.020b | 0.79 ± 0.01b | 5.64 ± 0.11b |

| CCl4+Sil(50 mg/kg) | |||

| Group IV | 1.05 ± 0.070b | 0.75 ± 0.05b | 3.75 ± 0.35 |

| CCl4+GA(50 mg/kg) | |||

| Group V | 4.50 ± 0.700b | 0.64 ± 0.01b | 5.11 ± 0.15b |

| CCl4+GA (100 mg/kg) |

Values are Mean ± SEM, n = 7 rats in each group. p < 0.05, a as compared with the normal control group; b as compared with the CCl4 only (group II).

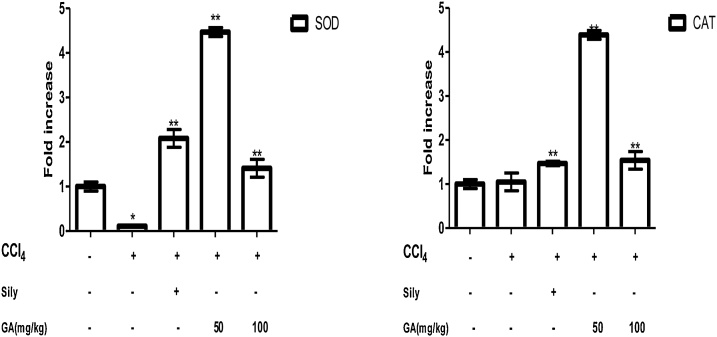

7.5. Stimulating effect of gallic acid on antioxidant (SOD and CAT) gene expression

The stimulating effect of gallic acid on antioxidant gene expression was evaluated in Fig. 3. The result shows that rats induced with CCl4 caused a down-regulation of the antioxidant gene compared to the control rats, but administration of gallic acid at a dose of 50 and 100 mg/kg up-regulated SOD and CAT gene. It was also observed that silymarin (50 mg/kg) significantly increase the SOD and CAT gene expression.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of gallic acid on SOD and CAT gene expressions determined by qPCR in CCl4 induced liver damage. Data are expresses as mean ± SEM (n = 7). * The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to the control; **The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to CCl4.

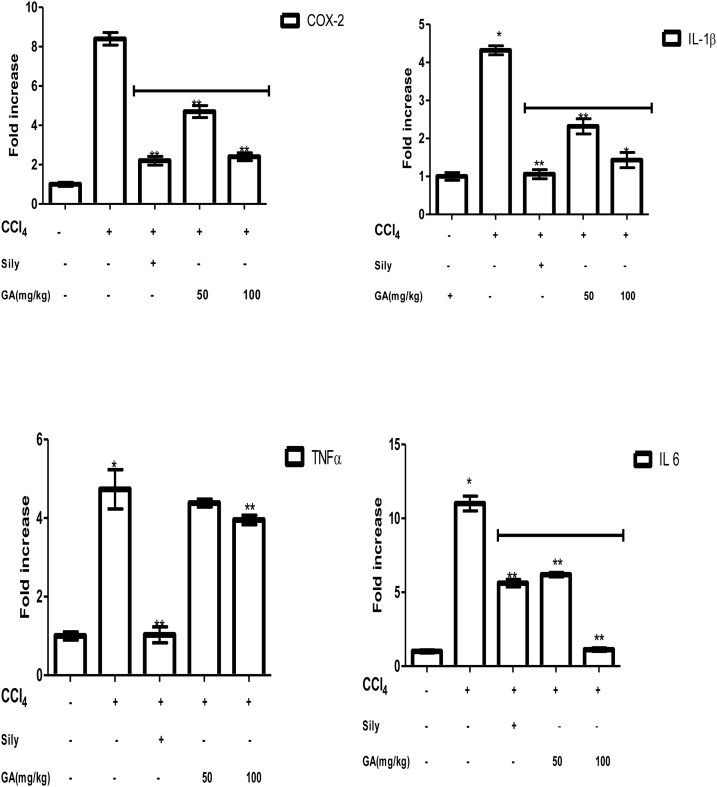

7.6. Inhibitory cause of gallic acid on some pro-inflammatory markers

The inhibitory cause of GA on some pro-inflammatory markers; tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase 2(COX-2), interleukin 1 beta, and 6 (IL-1β, and IL-6) were evaluated as shown in Fig. 4. The expression levels of the pro-inflammatory markers in rats intoxicated with CCl4 were remarkably increased compared to the control group (p < 0.05), however, treatment with gallic acid at the lower and higher doses was able to down-regulate the pro-inflammatory markers when compared to the CCl4 intoxicated group only. In the charts below, gallic acid reduces the fold increase of the pro-inflammatory cytokines; COX-2, IL1 β, IL-6, and TNF-α. It was observed that the 100 mg/kg dose is more effective in reducing the expression of cytokines. Furthermore, silymarin significantly decreases COX-2, IL1 β, IL-6, and TNF-α expression compared to rats induced with CCl4 only.

Fig. 4.

Effects of gallic acid on COX-2, IL-1, IL 6, and TNF-α expressions determined by qPCR in CCl4 induced liver damage. Data are expressed as Means ± SEM (n = 5)”. * The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to the control; **The mean is significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to CCl4.

7.7. Histological results

It was observed from the histological results that rats induced with CCl4 only causes large intracytoplasmic fat vacuoles (macrovesicular steatosis), vascular congestion, heavy periportal inflammatory infiltrates in the central vein, but treatment with silymarin and gallic acid protected the damaged liver. It was examined that the higher GA dose of 100 mg/kg showed remarkable liver regeneration with improved features like normal hepatocytes, mild portal vascular Congestion, and kupffer cell activation (Figure 5).

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph of liver sections I- Control, rats given water only, A: normal hepatocytes, B: sinusoids, C: central vein and D: portal vein, II- rat given CCl4 only showing A: large intracytoplasmic fat vacuoles (macrovesicular Steatosis), B: vascular congestion and C: heavy periportal inflammatory infiltrates, III-rats given CCl4+Sylimarin showing A: normal hepatocytes, B: mild portal congestion and C: mild periportal inflammatory infiltrates, IV-rat given CCl4+ 50 mg/kg gallic acid, showing A: normal hepatocytes, B: portal vascular Congestion and C: kupffer cell activation V-rat given CCl4+100 mg gallic acid showing A: normal hepatocytes, B: mild portal vascular Congestion and C: kupffer cell activation (H&E X100).

8. Discussion

Gallic acid (GA) is a naturally occurring phenolic compound with known antioxidant activities [28]. The current study showed that gallic acid possesses antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and anti-inflammatory effects as supported by the increased antioxidant enzyme activities, decreased plasma hepatic enzyme markers, and pro-inflammatory markers expression induced by carbon tetrachloride. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), a known model for causing liver injury, is enzymatically transformed by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP2E1) to produce trichloromethyl free radicals which are the toxic metabolite [29]. Trichloromethyl free radical initiates lipid peroxidation of the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum and causes oxidative damage. Also, there are alterations of transport function and membrane permeability in the damaged liver, which results in leak enzymes and other vital molecules from the cells into the bloodstream. Therefore, the excessive concentration of hepatic enzymes into the bloodstream indicates acute liver damage due to CCl4 intoxication [30].

In this study, a single dose of carbon tetrachloride administered to rats caused significant elevations of AST, ALT, ALP, and GGT activities when compared to the control group. Our results correlated with a previous report [31]. Conversely, treatment with GA at both the lower and higher doses attenuated the increased serum enzymes activities in CCl4-induced hepatic damage in Wistar rats (Fig. 2), which is in agreement with the report from other authors that “gallic acid decreased plasma AST and ALT activities that had been raised by acute hepatic damage” [32]. Wang et al. [33] observed that GA (15 mg/kg) reduced ALT, AST, and GGT when compared to CCl4-injured group. Administration of a known flavonoid, rutin at doses 50 and 70 mg/kg in the treatment of hepatotoxic CCl4-induced rat model showed similar results, with a significant reduction in the activities of serum enzymes ALT, AST and GGT [34]. The hepatoprotective potential of GA could have prevented the leaked intracellular enzymes by stabilizing the membrane and improving the antioxidant status. Furthermore, GA being an antioxidant may have mopped up free radicals produced in lipid peroxidation stimulated by CCl4 in vivo, in the process inhibiting the chain of reactions. It has also been reported that gallic acid reversibly inhibited CYP3A activity in human hepatic microsomes in vitro [35].

To further support our results that CCl4 caused injury to the liver, serum protein, and bilirubin were accessed (Table 2). It was observed that there was a significant increase in albumin concentration in rats intoxicated with CCl4 when compared to group I rats. However treatment with GA at a dose of 100 mg/kg significantly reduces albumin concentration when compared to group II, but at a lower dose of 50 mg/kg of GA there was a significant increase in albumin concentration when compared to group II rats. This was in agreement with Perazzoli et al. that plasma albumin level decreases after CCl4 intoxication and the effect recovered after GA and Dodecyl gallate treatments [36]. Also, there was a non-significant increase in total protein concentration in rats intoxicated with CCl4 when compared to the control. Treatment with GA at doses of 50 and 100 mg/kg body weight significantly increase total protein concentration in a dose-dependent manner when compared to group II rats.

Consequently, it was observed that gallic acid at both doses (50 and 100 mg/kg respectively) significantly reduce the increased concentration of bilirubin caused by CCl4 insult. There was also a significant increase in total protein and albumin concentrations and a significant decrease in serum bilirubin concentration in rats administered silymarin (50 mg/kg) when compared to group II. Marshall and Bangert reported that “plasma proteins are synthesized in the liver and its concentration in the plasma is in part a reflection of the functional capacity of the liver and its concentration tends to decrease in chronic liver diseases but is usually normal in the early stages of acute hepatitis owing to its long half-life” [37]. In liver diseases, bilirubin leaks out from either hepatocytes or the biliary system into the bloodstream when the usual route of excretion is obstructed (cholestasis).

To evaluate the oxidative stress parameters in CCl4 induced liver damage. Rats induced with CCl4 triggered a remarkable increase (p < 0.05) in the MDA levels caused by oxidative stress. This is in agreement with the research work of Ojeaburu and Oriakhi [38]. Szymonik et al. reported that “CCl4 metabolites react with polyunsaturated fatty acids to form covalent adducts with lipids and proteins that trigger the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation and the destruction of cell membranes with consequent hepatic damage” [39]. MDA is commonly used as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation. The elevated level of MDA in the CCl4 treated group (50 and 100 mg/kg of GA) was significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in comparison to the control group (Table 3). Similarly, there were significant decrease in the SOD, CAT activities, and GSH level due to hepatic injury caused by CCl4.This could be linked to the exhaustion of the antioxidant enzymes as a result of oxidative stress caused by CCl4 [39]. However, treatment with lower and higher doses of gallic acid significantly (p < 0.05) increase SOD and CAT activities in rats induced with CCl4. Also, a significant increase in GSH content was observed after post-treatment with gallic acid in a dose-dependent manner for 7 days (Table 4).

At the molecular levels, rats induced with CCl4 caused down regulation of SOD and CAT genes but treatment with gallic acid and silymarin up-regulated the antioxidant gene. Antioxidants mop up reactive oxygen species induced cellular damage thereby protecting the cells from injury [40]. In this study treatment with GA improved the antioxidant status of the oxidatively stressed rats. Our previous research suggested that “antioxidants exert their action in vivo by inhibiting the generation of reactive oxygen species by suppressing the CytP450 bioactivation of chemicals and drugs to reactive metabolites” [41]. Also, Aruoma and Kamalakkannan et al. reported that “antioxidants also carry out their mechanism of action by directly scavenging free radicals, a process known as mopping up, by up-regulating the expression of the genes coding for SOD, CAT, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase” [42,43]. This could be realized by stimulating “nuclear transcription factor erythroid-derived 2-like” causing the transactivation of antioxidant enzymes genes [44]. Gallic acid may covalently bind the sulfhydryl groups on Keap 1, causing the activation of Nrf2 [45], in the process, stimulates the antioxidant response elements (AREs) associated with NRF2 [46]. Therefore, the use of compounds able to activate NRF2‐KEAP1 pathway and induce genes involved in antioxidant defense appears to be a possible strategy in liver diseases [47].

Previous studies have also shown that green tea polyphenols such as (‐)‐epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate (EGCG) and (‐)‐epicatechin‐3‐gallate (ECG) are known NRF2 activators showing potent induction of ARE‐mediated luciferase activity [48]. EGCG potentiates cellular defense capacity against chemical carcinogens, UV, and oxidative stress via NRF2‐mediated induction of genes coding for antioxidants, modulators of inflammation, cell growth, apoptosis, cell adhesion, etc. [49].

Acute hepatic injury by carbon tetrachloride is a well-established animal model. In acute liver disease the liver is inflamed and the inflamed cells of the liver releases cytokines and these cytokines modulate gene expression in hepatocytes. The present study revealed the increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines; COX 2, IL-1ß, IL-6, and TNF-α after inducing liver damage with CCl4. Conversely, treatment with gallic acid at lower and higher doses significantly (p < 0.05) reduces the increased expression of these cytokines. These findings corroborated previous report that “gallic acid suppresses hepatoxicity by down-regulating both mRNA and protein levels of inflammatory cytokines including, cyclooxygenase-2, interleukin-1, IL-6, and TNF-α” [50]. Upregulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines in CCl4 induced liver damage may have activated the NF-κB signally pathway, which plays a key role in the up-regulation of cytokines [[51], [52], [53]]. Administration of gallic acid for 7 days suppresses the activation of the mRNA expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines in the rats administered CCl4 (groups IV and V). Therefore gallic acid attenuated CCl4-intoxicated hepatic damage in rats, probably by stimulating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes and downregulating the inflammatory mediators through the NF-κB inhibition pathway. Histological analysis of rats induced with CCl4 revealed centrilobular necrosis, vascular congestion, and hepatic necrosis, but the groups treated with silymarin, and gallic acid had liver returned to normalcy. The protective effect of gallic acid in the compromised liver may be as a result of its antioxidant properties (Figure 5).

9. Conclusion

In summary, it is important to note that the hepatoprotective effect of GA is arbitrated through the scavenging of free radicals, inhibition of malondialdehyde levels, activation of antioxidant enzymes, and down-regulation of pro-inflammatory markers.

Author’s contribution

SIO and KO conceptualize, planned, and supervised the research project. KO performed literature searches, carried out animal experiments and laboratory analyses. KO analyzed the data; SIO and KO prepared and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research project did not receive any funds from any agency. It was self-funding

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Natural Product Research and Disease Control Laboratory (NPRDC), Department of Biochemistry, University of Benin for providing the facilities needed to carry out this study. The authors also thank the following persons; Miss Itorho Ufuoma, Lydia, Miss Baker Benita, Ezekiel, Odunayo Destiny and Emmanuel for their technical support.

Edited by Dr. A.M Tsatsaka

References

- 1.Zamora Nava L.E., Aguire Valadez J., Chavez-Tapia N.C., Torre A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manage. 2014;10:295–303. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S59723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karakus E., Karadeniz A., Simsek N. Protective effect of Panax ginseng against serum biochemical changes and apoptosis in liver of rats treated with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;195:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waller R.L., Glende E.A., Recknagel R.O. CCl4 and bromotrichloromethane toxicity: dual role of covalent binding of metabolic cleavage products and lipid peroxidation in depression of microsomal calcium sequestration. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1983;32:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dragomir A.C., Sun R., Mishin V., Hall L.B., Laskin J.D., Laskin D.L. Role of galectin-3 in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity and inflammatory mediator production. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;127:609–619. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellezza I., Tucci A., Galli F., Grottelli S., Mierla A.L., Pilolli F., Minelli A. Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation via HO-1 activation underlies alpha-tocopheryl succinate toxicity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23:1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brigelius-Flohe R., Flohe L. Basic principles and emerging concepts in the redox control of transcription factors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;15:2335–2381. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D.F., Kuo H.P., Liu M., Chou C.K., Xia W., Du Y., Shen J., Chen C.T., Huo L., Hsu M.C. KEAP1 E3 ligase-mediated downregulation of NF-κB signaling by targeting IKKβ. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kensler T.W., Wakabayashi N., Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47(2007):89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubio V., Zhang J., Valverde M., Rojas E., Shi Z.Z. Essential role of Nrf2 in protection against hydroquinone-and benzoquinone-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2011;25(2011):521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komatsu M., Kurokawa H., Waguri S., Taguchi K., Kobayashi A., Ichimura Y., Sou Y.S., Ueno I., Sakamoto A., Tong K.I. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12(2010):213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji L.L., Sheng Y.C., Zheng Z.Y., Shi L., Wang Z.T. The involvement of p62– Keap1–Nrf2 antioxidative signaling pathway and JNK in the protection of natural flavonoid quercetin against hepatotoxicity. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015;85:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf A.T., Maurer R., Glickman J., Grace N.D. Hepatic venous pressure gradient supplements liver biopsy in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008;42:199–203. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225681.45088.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kris-Etherton P.M., Hecker K.D., Bonanome A., Coval S.M., Binkoski A.E., Hilpert K.F., Griel A.E., Etherton T.D. Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 2002;113:71–88. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00995-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borde V.U., Pangrikar P.P., Tekale S.U. Gallic acid in Ayurvedic herbs and formulations. Recent Res. Sci. Technol. 2011;3:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao J., Khan I.A., Fronczek F.R. Gallic acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online. 2011;67(2):o316–o317. doi: 10.1107/S1600536811000262. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Tang L., White J., Fang J. Inhibitory effect of gallic acid on CCl4 -mediated liver fibrosis in mice. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014;69:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NIH . 1985. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. NIH publication No. 85–23, Revised 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reitman S., Frankel S.A. Colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamate-oxaloacetate and pyruvate transaminass. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1957;28:56–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kochmar J.F., Moss D.W. Determination of alkaline phosphatase. In: Tietz N.W., editor. Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry. W.B. Saunders and company; Philadelphia: 1976. p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teitz N.N. Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry. ed 3. W. B Saunders Co; Philadelphia: 1987. Determination of gamma glutamyl transferase; p. 391. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tietz N.W., editor. Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests. 3rd ed. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jendrassik L., Grof P. Determination of direct and indirect bilirubin. Biochem. Z. 1938;1938:81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beutler E., Duron O., Kelly B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963;61:882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra H.P., Fridovich I. The role of superoxide anion in the autooxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for Superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:3170–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asru K.S. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal. Biochem. 1972;47:389–394. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buege J.A., Aust S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;1978:302–310. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar V., Abul K.A., Fausto K.N., editors. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tung Y., Wub J., Huang C., Peng H., Chen Y., Yang S. Protective effects of Acacia confusa bark extract and its active compound gallic acid against carbon tetrachloride-induced chronic liver injury in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;3:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brautbar N., Williams J. 2nd industrial solvents and liver toxicity: risk assessment, risk factors and mechanisms. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2002;205:479–491. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn T.H., Yang Y.S., Lee J.C., Moon C.J., Kim S.H., Jun W., Park S.C., Kim J.C. Ameliorative effects of pycnogenol on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic oxidative damage in rats. Phytother. Res. 2007;21:1015–1019. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oriakhi K., Uadia P.O., Eze G. Hepatoprotective potential of methanol extract of Tetracarpidum conophorum seeds in carbon tetrachloride induced liver damage. Clin. Phytoscience. 2017;4:25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locatelli C., Filippi-Monteiro F.B., Creezynski-pasa T.B. Alkyl esters of gallic acid as anticancer agents: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;20:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D., Zhao Y., Sun Y., Yang X. Protective effect of Ziyang tea polysaccharides on CCl4 –induced oxidative liver damage in mice. Food Chem. 2014;143:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jadon A., Bhadauria M., Shukla S. Protective effect of Terminalia belerica Roxb and gallic acid against carbon tetrachloride induced damage in albino rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perazzoli M.R.A., Perondi C.K., Baratto C.M., Winter E., Creczynski-Pasa T.B., Locatelli C. Gallic acid and dodecyl gallate prevents carbon tetrachloride-induced acute and chronic hepatotoxicity by enhancing hepatic antioxidant status and increasing p53 expression. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017;40:425–434. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stupans L., Tan H.W., Kirlich A., Tuck K., Hayball P., Murray M. Inhibition of CYP3A-mediated oxidation in human hepatic microsomes by the dietary derived complex phenol, gallic acid. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002;54:269–275. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall W., Bangert S. Clinical Chemistry. 6th edition. 2007. Plasma proteins and enzymes; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ojeaburu S.I., Oriakhi K. Effect of ethanol extract of Phyllantus niruri leaf on carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;2(7):349–354. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szymonik S., Czechokska G., Stryjecka-Zimmer M., Slomka M., Madro A., Celinski K., Wielosz M. Catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase activities in various rat tissues after carbon tetrachloride intoxication. J. Hepatobiliary. Surg. 2003;10(4):309–315. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0824-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia X.Y., Zhang Q.A., Zhang Z.Q., Wang Y., Yuan J.F., Wang H.Y., Zhao D. Hepatoprotective effects of almond oil against carbon tetrachloride induced liver injury in rats. Food Chem. 2011;125:673–678. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blokhina O., Virolainen E., Fagerstedt K.V. Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann. Bot. 2003;91:179–194. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aruoma O.I. Free radical, antioxidants and international nutrition. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999;8(1):53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamalakkannan N., Rukkumani R., Aruna K., Varma P.S., Viswanathan P., Menon V.P. Protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage. Iran. J. Pharm. Ther. 2005;42:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martín M.A., Ramos S., Granado-Serrano A.B., Rodríguez R.I., Trujillo M., Bravo L., Goya L. Hydroxytyrosol induces antioxidant/detoxificant enzymes and Nrf2 translocation via extracelular regulated kinases and phosphatidylinositol-3kinase/protein kinase B pathways in HepG2 cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010;54:956–966. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ou Y., Zheng S., Lin L., Jiang Q. Protective effect of C-phycocyanin against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatocyte damage in vitro and in vivo. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;185:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mard S., Mojadami S., Farbood Y., Gharib N.M. The anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of gallic acid against mucosal inflammation and erosins-induced by gastric ischemia reperfusion in rats. Vet. Res. Forum. 2015;6:305–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sova M., Saso L. Design and development of Nrf2 modulators for cancer chemoprevention and therapy: a review. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018;12:3181–3197. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S172612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mascuch S.J., Boudreau P.D., Carland T.M., Pierce N.T., Olson J., Hensler M.E., Choi H., Campanale J., Hamdoun A., Nizet V. Marine natural product honaucin a attenuates inflammation by activating the Nrf2‐ARE pathway. J. Nat. Prod. 2018;81:506–514. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kubo E., Chhunchha B., Singh P., Sasaki H., Singh D.P. Sulforaphane reactivates cellular antioxidant defense by inducing Nrf2/ARE/Prdx6 activity during aging and oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14130. doi: 10.1038/s41598‐017‐14520‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen C., Yu R., Owuor E.D., Kong A.N. Activation of antioxidant‐response element (ARE), mitogen‐ activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and caspases by major green tea polyphenol components during cell survival and death. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2000;23:605–612. doi: 10.1007/bf02975249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Na H.K., Surh Y.J. Modulation of Nrf2‐mediated antioxidant and detoxifying enzyme induction by the green tea polyphenol EGCG. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farombi E.O., Shrotriya S., Surh Y.J. Kolaviron inhibits dimethyl nitrosamine-induced liver injury by suppressing COX-2 and iNOS expression via NF-κB and AP-1. Life Sci. 2009;84:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Surh Y.J., Chun K.S., Cha H.H., Han S.S., Keum Y.S., Park K.K., Lee S.S. Molecular mechanisms underlying chemopreventive activities of anti-inflammatory phytochemicals: down-regulation of COX-2 and iNOS through suppression of NF-κB activation. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2001;480:243–268. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]