Abstract

Purpose

Assessment of liver fibrosis is essential for the management of liver disease. Although liver biopsy is the gold-standard modality for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, it has some limitations. Thus, other methods are required to overcome the disadvantages of a liver biopsy. T1ρ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) values are potential biomarkers for liver cirrhosis. This study aimed to assess the relationship between T1ρ MRI values and liver fibrosis severity by measuring the correlation between T1ρ values and shear wave elastography (SWE) values, which are routinely used for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis.

Methods

T1ρ imaging and SWE values were obtained from four healthy volunteers and 16 patients with chronic liver disease. The regions of interest on MR images were drawn and matched with those of the right liver lobe on SWE images.

Results

The mean T1ρ values of the right liver lobe correlated positively with the mean SWE values (Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.783; p < 0.0001; 95 % confidence interval: 0.623–0.880).

Conclusion

The mean T1ρ values of the right liver lobe may be correlated with the severity of liver fibrosis.

Abbreviations: ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ROI, region of interest; SD, standard deviation; SLT, spin-lock time; SWE, shear-wave elastography

Keywords: Liver, Fibrosis, Magnetic resonance imaging, Diagnostic imaging

1. Introduction

The degree of liver fibrosis is an important diagnostic and prognostic parameter in the assessment of chronic liver disease. Progression of liver fibrosis can lead to cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and liver failure. Assessment of liver fibrosis is, therefore, essential for the management of patients with liver disease.

Liver biopsy is the gold-standard modality for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis; however, it has some limitations. First, it is an invasive procedure and can cause complications, such as significant haemorrhaging, which might occasionally lead to the death of patients [1,2]. Therefore, this procedure is not ideal for repetitive assessments of disease progression. Second, there is a risk of sampling error [3,4]. Third, it is a relatively expensive procedure, although the cost may vary depending on the country. Therefore, reproducible and reliable non-invasive methods are needed to assess the progression of liver fibrosis.

Ultrasonographic elastography and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) have been reported to be the most optimal modalities for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis severity [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. Although ultrasonographic elastography is a non-invasive method with a high level of repeatability and reproducibility [11,12], the range of observation is limited, and operators require training to obtain consistent measurements [12]. Similarly, MRE has also been reported to correlate well with the assessment of liver fibrosis severity. However, MRE requires a passive acoustic driver to generate continuous longitudinal mechanical waves, limiting the use of this technique to specialised medical centres, thus, drastically reducing its availability and making it difficult to perform daily.

T1ρ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sensitive to the interactions between water molecules and macromolecules, including collagen [13,14]. T1ρ MRI findings have been reported to correlate with renal fibrosis [15] and myocardial fibrosis [16,17]. It has been found that T1ρ magnetic resonance (MR) images can monitor liver fibrosis in rats [18], and T1ρ value has been reported to be a potential MR biomarker for liver cirrhosis [[18], [19], [20]]. Moreover, since the acquisition of T1ρ MR images does not require additional equipment or advanced analysis software, they can be used for daily evaluations of liver fibrosis.

This study aimed to elucidate the relationship between T1ρ values and the severity of liver fibrosis by measuring the correlation between the values of T1ρ MRI and shear wave elastography (SWE) that were used for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis.

2. Materials and methods

This prospective, single-centre study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in this study.

2.1. Healthy volunteers

Four healthy volunteers (mean age, 30 years; range, 26–46 years), with no history of liver disease or alcoholism, underwent T1ρ MRI of the liver and SWE on the same day between July 2016 and January 2017.

2.2. Patients

We included patients with chronic liver disease and excluded patients with active cancer, which was defined by laboratory data and radiological images acquired between July 2016 and January 2017. Eighteen patients with chronic liver disease underwent T1ρ MRI and SWE. SWE was performed within 1 week before or after T1ρ MRI.

2.3. MRI data

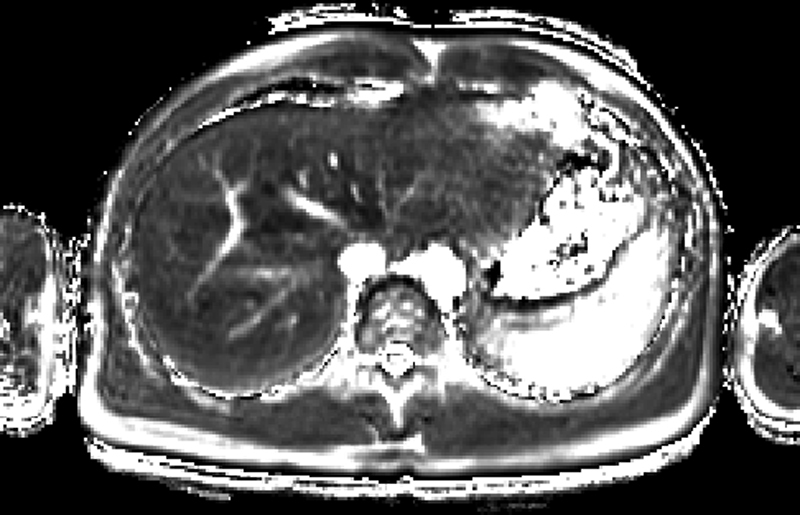

MRI was performed using a 3.0-T scanner (Achieva; Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) with a 32-channel torso coil. The breath-hold technique was used to minimise respiratory motion artefacts. Volume shimming was used to minimise B0 inhomogeneity. In addition, a rotary echo spin-lock pulse was used in a two-dimensional fast field-echo sequence for the acquisition of T1ρ–weighted data, with a spin-lock frequency of 1,000 Hz at spin-lock times (SLTs) of 0, 10, 20, 40, and 60 ms. The other imaging parameters were as follows: repetition time ms/echo time, 4.3/2.2 ms; flip angle, 10°; number of signals acquired, 1; specific absorption rate, < 0.7 W/kg; field of view, 360 mm; section thickness, 10 mm; acquisition matrix, 2.25 mm × 2.23 mm; and reconstruction matrix, 1.41 mm × 1.41 mm. A total of 11 images were acquired per patient, which enabled coverage of the whole liver in 1 min and 30 s for each SLT. This resulted in a total acquisition time of approximately 12 min (depending on each individual’s respiratory frequency). Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the sample images.

2.4. SWE measurement

Two-dimensional SWE was performed using an Aplio 500 Platinum system (Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan) with a 6-MHz convex probe. This device measures the velocity of shear wave propagation, which is used to estimate tissue stiffness. These quantitative values were also mapped as colour-coded two-dimensional SWE images of tissue stiffness, which was generated simultaneously with conventional B-mode images. SWE was performed by a radiologist with 9 years of experience. Each SWE value was obtained from two lesions in the right liver lobe because the mean SWE values obtained from the right liver lobe have been well-documented previously for the assessment of liver fibrosis severity [6]. Patients were not sedated during the procedure. The right lobe measurements were obtained at a minimum depth of 3 cm, and up to 5 cm from the skin surface, using an intercostal acoustic window. Two regions of interest (ROIs) were identified within each SWE image with shear wave velocity. The largest possible ROIs that did not include blood vessels, portal tracts, and focal lesions treated by trans-arterial chemoembolisation were selected for analysis. Mean elasticity values were calculated for each of the two measurement sites.

2.5. Image analysis

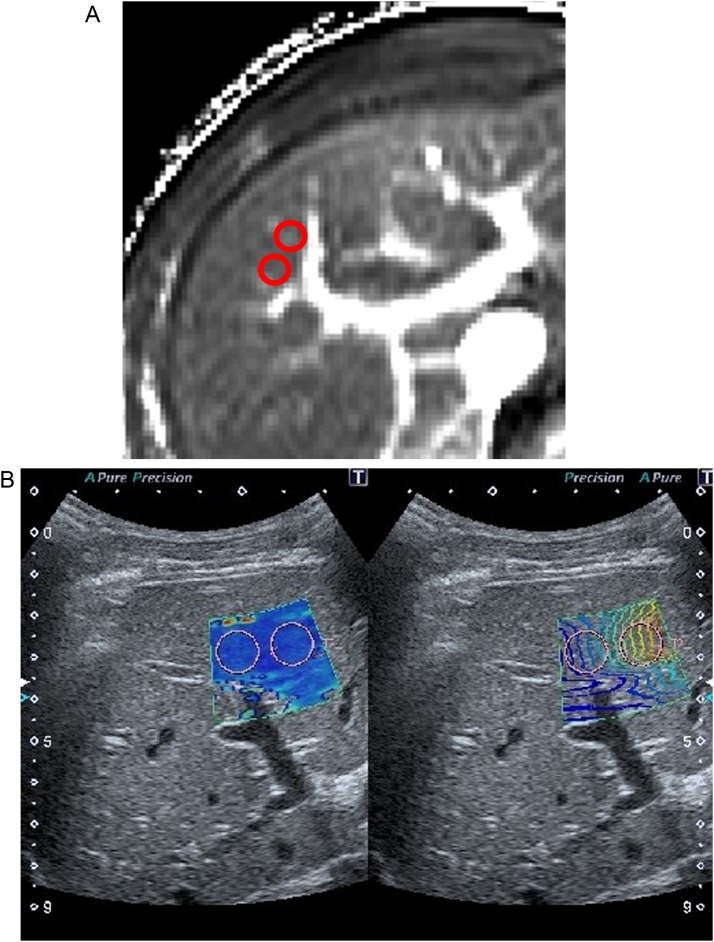

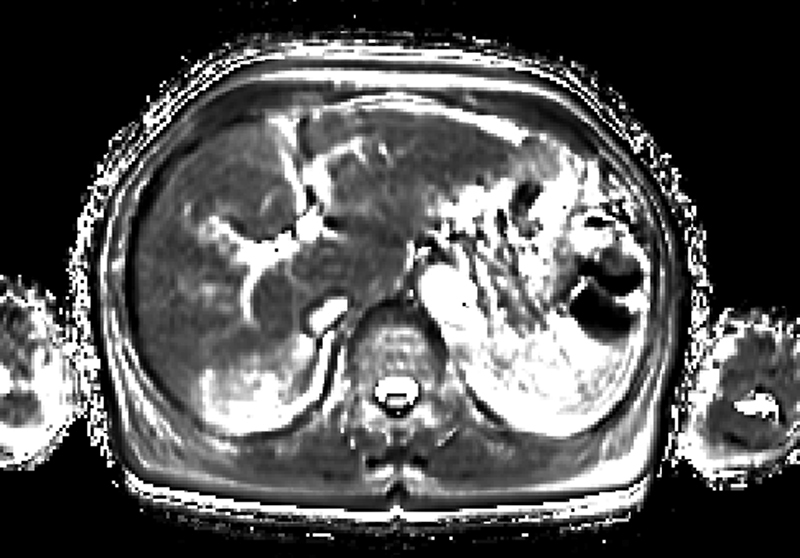

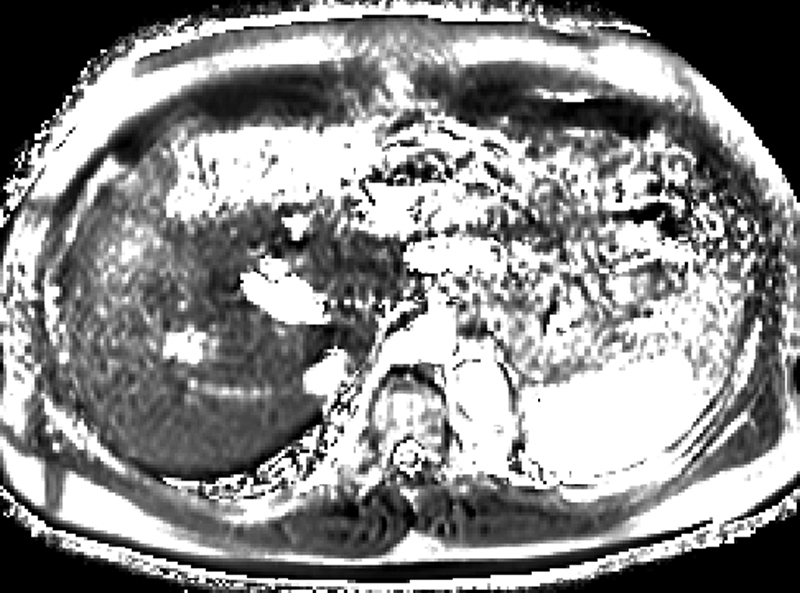

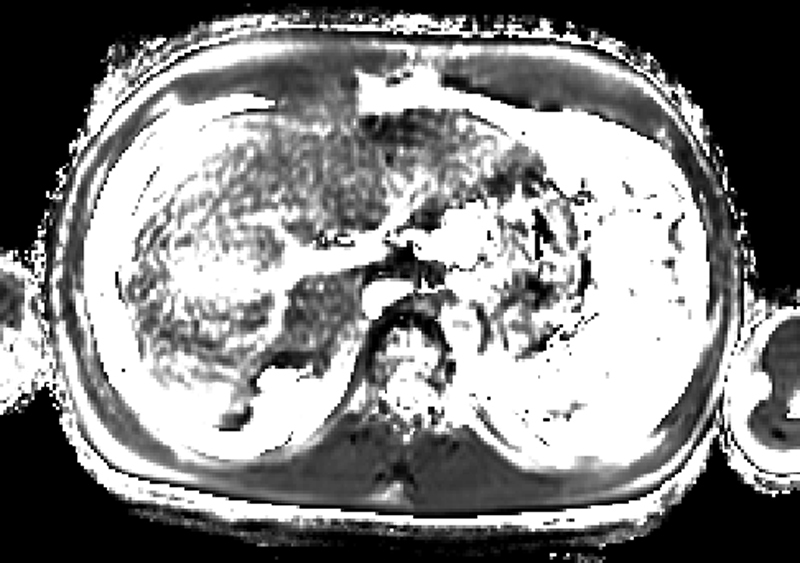

The ROIs on the MR images were acquired to match the regions of the liver with SWE (Fig. 1), with reference to the portal and hepatic veins by the radiologist who performed SWE. Images with severe artefacts were excluded.

Fig. 1.

The region of interest (ROI) settings. The ROIs on magnetic resonance and shear wave elastography images were acquired to match the region of the liver at the right lobe, referring to the hepatic segment and vessels.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The association between the mean T1ρ and mean SWE values were determined by Spearman rank correlation coefficient, estimated using MedCalc Version 17.8.1 software for Windows. Moreover, a linear mixed model analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 software to evaluate the difference between T1ρ values of volunteers and patients and to assess the relationship between the mean T1ρ values and the Child–Pugh score or albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade. We considered p-values < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

In two patients, the ROIs were not acquired on MR images due to severe artefacts that developed because of insufficient breath holding (Supplementary Fig. 2); therefore, the region of the liver selected for SWE could not be mapped, and the results of these patients were excluded from the analysis.

The characteristics of 16 patients (mean age, 68 years; range, 36–87 years) were as follows. The causes of chronic liver disease included hepatitis C (n = 8), alcoholism (n = 3), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 2), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (n = 1), hepatitis B (n = 1), and portal vein agenesis and chronic heart failure (n = 1). One patient with alcoholic liver disease underwent balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices. Another patient with alcoholic liver disease underwent percutaneous transhepatic obliteration for gastric varices. Two patients (one with hepatitis C and one with alcoholic liver disease) underwent trans-arterial chemoembolisation and were deemed tumour-free. Moreover, one patient with hepatitis C underwent left renal surgery for renal cell carcinoma. Finally, one patient with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease underwent surgical vesico-rectal fistula closure. The characteristics of all included patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Cause of chronic liver disease | n = 16 |

|---|---|

| Chronic viral hepatitis B | 1 |

| Chronic viral hepatitis C | 8 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3 |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 1 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 2 |

| Portal vein agenesis and chronic heart failure | 1 |

| Past history | n = 16 |

|---|---|

| Related to the liver | |

| Trans-arterial chemoembolisation | 2 |

| Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration | 1 |

| Percutaneous transhepatic obliteration | 1 |

| Unrelated to the liver | |

| Left renal surgery for renal cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Surgical closure of a vesico-rectal fistula | 1 |

3.2. Patients’ clinical data

A summary of the patients’ laboratory data is shown in Table 2, and a summary of the volunteers’ and patients’ Child–Pugh scores and ALBI grades are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of patients’ laboratory data.

| Parameters | Mean (range) | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| TB (mg/dL) | 1.52 (0.5–4.5) | 0.2–1.2 |

| DB (mg/dL) | 0.695 (0.1–2.8) | 0.1–0.4 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.85 (2.6–4.8) | 3.8–5.2 |

| AST (U/L) | 30.52 (15–51) | 8–30 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19.6 (8–34) | 5–35 |

| γGTP (U/L) | 22.6 (9–35) | 7–40 |

| Ch-E (U/L) | 252 (117–374) | 178–482 |

| NH3 (μg/dL) | 65.8 (22–225) | 18–65 |

| Plt (×104/μL) | 11.6 (4.7–21.6) | 15.0–40.0 |

| PT-INR | 1.07 (0.93–1.27) | 0.9–1.1 |

| PT (%) | 91.0 (58.2–119) | 80.0–110.0 |

| Cre (mg/dL) | 0.779 (0.39–1.19) | 0.44–0.78 |

TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; Alb, albumin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; γGTP, gamma-glutamyl transferase; Ch-E, cholinesterase; Plt, platelet count; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalised ratio; PT, prothrombin time; Cre, creatinine.

Table 3.

Patient distribution for the Child–Pugh scores and ALBI grades.

| Category | Score | n |

|---|---|---|

| Child–Pugh A | 5 | 10 |

| 6 | 1 | |

| 7 | 1 | |

| B | 8 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 | |

| C | 11 | 1 |

| ALBI grade | 1 | 10 |

|---|---|---|

| 2a | 0 | |

| 2b | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 |

ALBI, albumin-bilirubin.

3.3. Correlations between mean T1ρ and mean SWE values of the liver

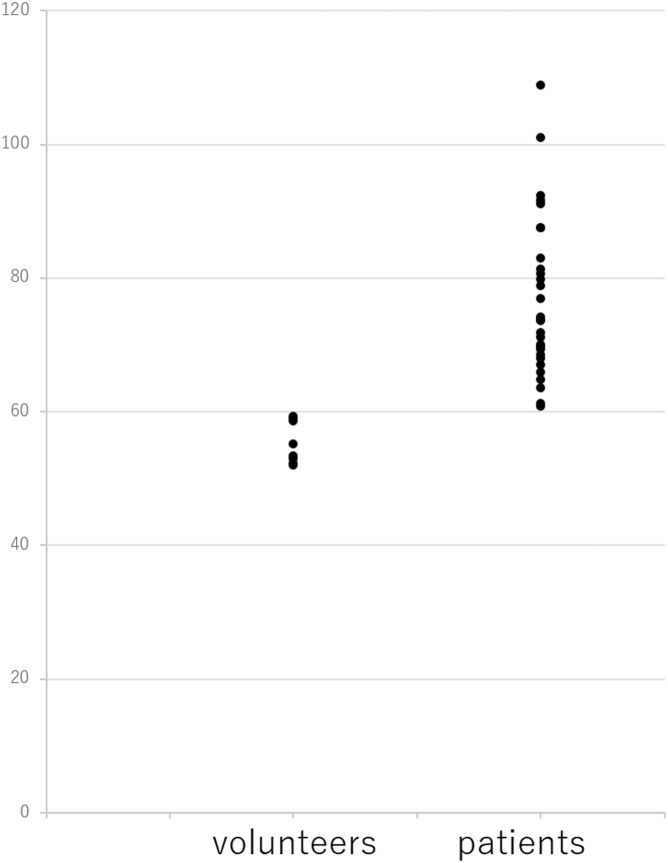

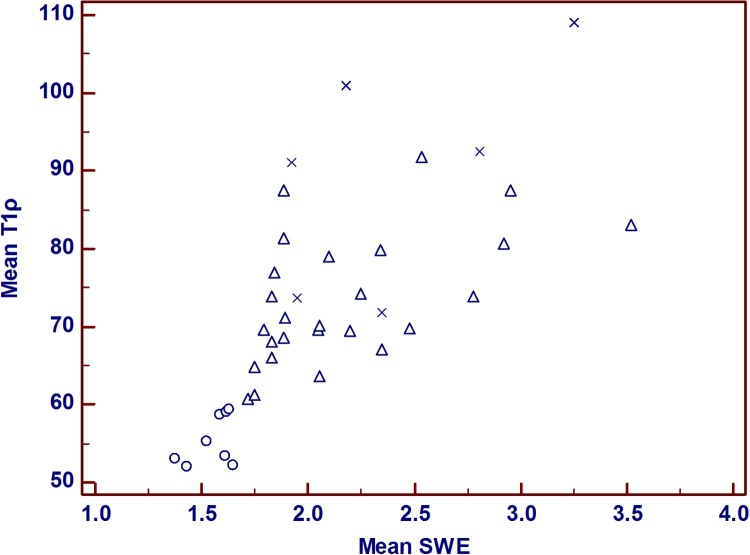

The mean T1ρ values in the healthy volunteers and patients with chronic liver disease were 55.4 (95 % confidence interval: 44.7–66.0) and 76.5 (95 % confidence interval: 71.2–81.8), respectively (p = 0.002) (Fig. 2). The mean SWE values in volunteers and patients with chronic liver disease were 1.55 m/s ± 0.102 standard deviation (SD) and 2.20 m/s ± 0.458 SD, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the mean T1ρ values and mean SWE values was 0.783 (p < 0.0001, 95 % confidence interval: 0.623–0.880), and Fig. 3 shows the scatterplots of the correlation between the mean T1ρ and mean SWE values.

Fig. 2.

T1ρ value distributions among volunteers and patients. The T1ρ values of volunteers are significantly lower than those of patients.

Fig. 3.

Scatterplots of the correlations between the mean T1ρ and the mean SWE values. Volunteers, ○; Child–Pugh A, △; Child–Pugh B, ×. This scatterplot shows a good correlation between the mean T1ρ and mean SWE values (Correlation coefficient of rank correlation: 0.783, p < 0.0001, 95 % confidence interval: 0.623–0.880). Abbreviation: SWE, shear wave elastography.

3.4. Correlations between mean T1ρ values of the liver and Child–Pugh scores or ALBI grades

The mean T1ρ values exhibited linear trends when compared with the Child–Pugh scores and ALBI grades (p = 0.005 and 0.007, respectively). Table 4, Table 5 present a summary of the data.

Table 4.

Correlations between mean T1ρ values of the liver and Child–Pugh scores.

| Child–Pugh score | n | N | Mean | 95 % CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteers | 4 | 8 | 55.4 | 48.9–61.8 | 0.001 (for trend) |

| 5 | 10 | 20 | 72.2 | 68.1–76.3 | |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 73.7 | 60.8–86.6 | |

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 69.1 | 56.1–82.0 | |

| 8 | 2 | 4 | 89.6 | 76.7–102.5 | |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | 98.4 | 89.2–107.5 | |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 72.8 | 59.9–85.7 |

n, number of patients; N, number of measurements.

CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Correlations between mean T1ρ values of the liver and ALBI grades.

| ALBI grade | n | N | Mean | 95 % CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteers | 4 | 8 | 55.4 | 46.6–64.2 | 0.001 (for trend) |

| 1 | 10 | 20 | 71.5 | 66.0–77.1 | |

| 2 | 3 | 6 | 88.8 | 78.6–98.9 | |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 80.8 | 70.7–91.0 |

n, number of patients; N, number of measurements.

ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; CI, confidence interval.

3.5. Follow-up

One patient (mean T1ρ value: 72.8, Child–Pugh score 11) has died due to liver dysfunction after 30 months. One patient (mean T1ρ value: 70.4, Child–Pugh score 5) died due to hepatocellular carcinoma progression after 29 months. One patient (mean T1ρ value: 80.7, Child–Pugh score 5) underwent endoscopic injection sclerotherapy after 46 months because of exacerbated oesophageal varices. Other patients (mean follow-up period: 39 months, including 5 patients who were lost to follow-up) had no events related to liver dysfunction. Table 6 present a summary of the data.

Table 6.

Events related to liver function.

| Patient No. | Mean T1ρ value | Follow-up duration (months) | Event | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 72.8 | 30 | Death | Liver dysfunction |

| 10 | 70.4 | 29 | Death | Progression of HCC |

| 14 | 80.7 | 46 | EIS | Exacerbation of oesophageal varices |

EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to examine the correlation between mean T1ρ and SWE values of the right liver lobe to assess the severity of liver fibrosis. We found that mean T1ρ values exhibited a strong positive correlation with mean SWE values, which suggested that the mean T1ρ values of the right liver lobe may be sufficiently correlated with the severity of liver fibrosis. The four advantages of T1ρ imaging are as follows: First, the mean T1ρ values are useful to evaluate a large part of the liver, whereas liver biopsy only provides access to a small portion of the liver parenchyma (1/50,000th) [1]. Even ultrasound sonography only allows access equivalent to a 1 × 4 cm3 cylindrical region of the liver, which corresponds to approximately 1/500th the area of the liver [7]. Uneven distribution throughout the liver parenchyma could be a reason for sampling errors observed during the evaluation of liver fibrosis [3]. Second, T1ρ values are objective. Third, T1ρ MR images can also be obtained while performing other radiological imaging, such as gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI or gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced MRI, without the need for specialised devices. Fourth, when the ROIs on the MRI scans are acquired for evaluating liver fibrosis, they only need to avoid blood vessels, portal tracts, and focal lesions. Therefore, the operator’s experience may not affect the result. Thus, these aspects of T1ρ are beneficial for repetitive examinations, as well as the assessment of the heterogeneous character and changes in the liver over time.

Previous research has provided several recommendations for identifying ROIs, such as placing the ROI in a circle and excluding the main blood vessel or placing the ROI in accordance with the shape of the liver [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. Studies have also reported that the stiffness of the liver changes significantly depending on the regions of measurement in MRE [23]. In the current study, the ROIs for T1ρ images and SWE were set to be as consistent as possible with reference to the vessels. Major blood vessels were also avoided during ROI selection, and focal legions were used to measure the correlation between mean T1ρ and SWE values.

A block pulse was used as a spin-lock pulse in other studies, and several artefacts can be observed because of B0 and B1 inhomogeneity of the liver. The spin-lock sequences using stretched-type adiabatic pulses have been reported to provide homogeneous liver T1ρ images and reduce artefacts [26]. In the present study, T1ρ images were acquired with the spin locking sequence using stretched-type adiabatic pulses. Only two patients were excluded from analysis in this study owing to the presence of severe artefacts, which occurred because of insufficient breath holding.

The reproducibility of T1ρ MRI was not evaluated in this study. However, this study was performed at a single centre with only one MRI scanner. Therefore, there was no variation due to the differences in the MRI apparatus or centres.

Mean SWE values in people without liver disease, cardiac disease, or malignancy were reported as 1.32 ± 0.13 m/s (range, 1.06–1.60 m/s) [27]. The mean SWE values in people with mixed-aetiology chronic liver disease ranged between 1.49 and 5.30 m/s [28]. In our study, the mean SWE values in volunteers were 1.55 m/s ± 0.102 SD, and the mean SWE values ranged between 1.43 and 2.95 m/s. Those values were compatible with previous reports [27,28]. The mean T1ρ values were previously reported to be 47.8 ± 4.2 ms in healthy people and 57.4 ± 7.4 ms in patients with liver cirrhosis [20]. These published values are lower than those in our study. The reason may be that the adiabatic pulses used in our study have a higher spin-lock frequency (1,000 Hz) than those with block pulse (500 Hz) used in the previous study [20]. As reported previously, T1ρ values acquired with adiabatic pulses are higher than those acquired with block pulses [26]. In addition, the slice thickness was larger in our study (10 mm) than in the previous study (5 mm). This may lead to smaller signals which are easily drowned out by noise, resulting in higher T1ρ values.

The mean T1ρ values estimated for the right liver lobe correlated well with the Child–Pugh scores and ALBI grades. The correlation between mean T1ρ values and Child–Pugh scores has been reported previously [19]. Although the current study had a small sample size and lacked statistical power, the results were consistent with those reported by previous studies. However, the follow-up duration was short, and almost all patients had no events, making it difficult to show any relationship between T1ρ value and patients’ prognosis. Therefore, this study needed a longer follow-up duration.

Despite its strengths, this study had some limitations. First, there were no correlations with the biopsy data in this study. Second, the mean T1ρ values of the left liver lobe were not assessed because the mean SWE values of the left liver lobe did not show a good correlation with the severity of liver fibrosis [6]. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether the T1ρ values of the left liver lobe correlate with the severity of liver fibrosis. Third, although it is known that fibrosis patterns differ among liver diseases, our study population was affected by a range of liver diseases. Nevertheless, the mean SWE values, obtained from the right liver lobe of patients with various liver diseases, correlated well with the severity of liver fibrosis [6]. Our study results demonstrated a positive correlation between mean T1ρ and mean SWE values. Therefore, the mean T1ρ values of the right liver lobe may correlate with fibrosis severity, irrespective of the type of liver disease. Fourth, this was a prospective study with only a small patient population and a limited number of volunteers. Thus, further studies with larger populations of patients with liver diseases are needed in the future to establish the utility of T1ρ for determining the severity of liver fibrosis.

5. Conclusion

Within the study limitations, the mean T1ρ values of the right liver lobe correlated with the severity of liver fibrosis.

Funding statement

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, YS, upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yohsuke Suyama: Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Kengo Tomita: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Shigeyoshi Soga: Data curation. Hiroshi Kuwamura: Investigation. Wakana Murakami: Data curation, Formal analysis. Ryota Hokari: Conceptualization. Hiroshi Shinmoto: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2021.100321.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bravo A.A., Sheth S.G., Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:495–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockey D.C., Caldwell S.H., Goodman Z.D., Nelson R.C., Smith A.D. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017–1044. doi: 10.1002/hep.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedossa P., Dargère D., Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regev A., Berho M., Jeffers L.J., Milikowski C., Molina E.G., Pyrsopoulos N.T., Feng Z.Z., Reddy K.R., Schiff E.R. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder J., Patel K. The clinical utility of FibroScan® as a noninvasive diagnostic test for liver disease. Med. Devices (Auckl) 2014;7:107–114. doi: 10.2147/mder.s46943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samir A.E., Dhyani M., Vij A., Bhan A.K., Halpern E.F., Méndez-Navarro J., Corey K.E., Chung R.T. Shear-wave elastography for the estimation of liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease: determining accuracy and ideal site for measurement. Radiology. 2015;274:888–896. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shire N.J., Yin M., Chen J., Railkar J.R.A., Fox‐Bosetti S., Johnson S.M., Beals C.R., Dardzinski B.J., Sanderson S.O., Talwalkar J.A., Ehman R.L. Test-retest repeatability of MR elastography for noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment in hepatitis C. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2011;34:947–955. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Y.S. Ultrasound evaluation of liver fibrosis. J. Med. Ultrasound. 2017;25:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jmu.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castera L. Noninvasive methods to assess liver disease in patients with hepatitis B or C. Gastroenterology. 2012;142 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.017. 1293–1302.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ichikawa S., Motosugi U., Morisaka H., Sano K., Ichikawa T., Tatsumi A., Enomoto N., Matsuda M., Fujii H., Onishi H. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracies of magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography for hepatic fibrosis. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2015;33:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller M., Gennisson J.L., Deffieux T., Tanter M., Fink M. Quantitative viscoelasticity mapping of human liver using supersonic shear imaging: preliminary in vivo feasibility study. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2009;35:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferraioli G., Tinelli C., Zicchetti M.M., Above E., Poma G., Di Gregorio M., Filice C. Reproducibility of real-time shear wave elastography in the evaluation of liver elasticity. Eur. J. Radiol. 2012;81:3102–3106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menezes N.M., Gray M.L., Hartke J.R., Burstein D. T2 and T1ρ MRI in articular cartilage systems. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;51:503–509. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santyr G.E., Henkelman R.M., Bronskill M.J. Spin locking for magnetic resonance imaging with application to human breast. Magn. Reson. Med. 1989;12:25–37. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hectors S.J., Bane O., Kennedy P., El Salem F., Menon M., Segall M., Khaim R., Delaney V., Lewis S., Taouli B. T1ρ mapping for assessment of renal allograft fibrosis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2019;50:1085–1091. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Oorschot J.W., Guclu F., de Jong S.S., Chamuleau S.A., Luijten P.R., Leiner T., Zwanenburg J.J. Endogenous assessment of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in patients with T1ρ-mapping. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2017;45:132–138. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C., Zheng J., Sun J., Wang Y., Xia R., Yin Q., Chen W., Xu Z., Liao J., Zhang B., Gao F. Endogenous contrast T1rho cardiac magnetic resonance for myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. J. Cardiol. 2015;66:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao F., Wang Y.X., Yuan J., Deng M., Wong H.L., Chu E.S., Go M.Y., Teng G.J., Ahuja A.T., Yu J. MR T1ρ as an imaging biomarker for monitoring liver injury progression and regression: an experimental study in rats with carbon tetrachloride intoxication. Eur. Radiol. 2012;22:1709–1716. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allkemper T., Sagmeister F., Cicinnati V., Beckebaum S., Kooijman H., Kanthak C., Stehling C., Heindel W. Evaluation of fibrotic liver disease with whole-liver T1ρ MR imaging: a feasibility study at 1.5 T. Radiology. 2014;271:408–415. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauscher I., Eiber M., Ganter C., Martirosian P., Safi W., Umgelter A., Rummeny E.J., Holzapfel K. Evaluation of T1ρ as a potential MR biomarker for liver cirrhosis: comparison of healthy control subjects and patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2014;83:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsufuji T., Shinagawa Y., Fujimitsu R., Urakawa H., Inoue K., Takano K., Yoshimitsu K. Measurement consistency of MR elastography at 3.0 T: comparison among three different region-of-interest placement methods. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2013;31:336–341. doi: 10.1007/s11604-013-0195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva A.M., Grimm R.C., Glaser K.J., Fu Y., Wu T., Ehman R.L., Silva A.C. Magnetic resonance elastography: evaluation of new inversion algorithm and quantitative analysis method. Abdom. Imaging. 2015;40:810–817. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusak G., Zawada E., Lemanowicz A., Serafin Z. Whole-organ and segmental stiffness measured with liver magnetic resonance elastography in healthy adults: significance of the region of interest. Abdom. Imaging. 2015;40:776–782. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesh S.K., Yin M., Ehman R.L. Magnetic resonance elastography of liver: technique, analysis, and clinical applications. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2013;37:544–555. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y., Lee J.M., Lee J.E., Lee K.B., Lee E.S., Yoon J.H., Yu M.H., Baek J.H., Shin C.I., Han J.K., Choi B.I. MR elastography for noninvasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis: reproducibility of the examination and reproducibility and repeatability of the liver stiffness value measurement. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2014;39:326–331. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuaki T., Takayama Y., Nishie A., Ogino T., Obara M., Honda H., Miyati T., Van Cauteren M. T1ρ mapping improvement using stretched-type adiabatic locking pulses for assessment of human liver function at 3T. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2017;40:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trout A.T., Xanthakos S.A., Bennett P.S., Dillman J.R. Liver shear wave speed and other quantitative ultrasound measures of liver parenchyma: prospective evaluation in healthy children and adults. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020;214:557–565. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadebaum D.P., Nicoll A.J., Sood S., Gorelik A., Gibson R.N. Variability of liver shear wave measurements using a new ultrasound elastographic technique. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:647–656. doi: 10.1002/jum.14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, YS, upon reasonable request.