Abstract

Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) and trehalase (TRE) directly regulate trehalose metabolism and indirectly regulate chitin metabolism in insects. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and RNA interference (RNAi) were used to detect the expressions and functions of the ApTPS and ApTRE genes. Abnormal phenotypes were found after RNAi of ApTRE in the Acyrthosiphon pisum. The molting deformities were observed in two color morphs, while wing deformities were only observed in the red morphs. The RNAi of ApTPS significantly down-regulated the expression of chitin metabolism-related genes, UDP-N-acetyglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (ApUAP), chitin synthase 2 (Apchs-2), Chitinase 2, 5 (ApCht2, 5), endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase (ApENGase) and chitin deacetylase (ApCDA) genes at 24 h and 48 h; The RNAi of ApTRE significantly down-regulated the expression of ApUAP, ApCht1, 2, 8 and ApCDA at 24 h and 48 h, and up-regulated the expression of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (ApGPI) and Knickkopf protein (ApKNK) genes at 48 h. The RNAi of ApTRE and ApTPS not only altered the expression of chitin metabolism-related genes but also decreased the content of chitin. These results demonstrated that ApTPS and ApTRE can regulate the chitin metabolism, deepen our understanding of the biological functions, and provide a foundation for better understanding the molecular mechanism of insect metamorphosis.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Developmental biology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Chitin is a polymer of N-acety1-β-d-glucosamine and also a major component of the insect cuticle. It is vital to the peritrophic matrix, which acts as a permeability barrier between food and midgut epithelium, promotes digestion and protects the brush border from mechanical disruption1,2. The biosynthesis and degradation of chitin are influenced by enzymes, food substrates, energy suppliers and intracellular environment3. Rate-limiting enzymes, glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT), UDP-N-acetyglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (UAP), and chitin synthase (CHS) are the major sites for chitin synthesis3. CHS activity influences chitin content4; trehalose, glycogen and glucose are used for the metabolic production of adenosine triphosphates and structural materials for chitin biosynthesis3,5,6; CHS activity is dependent on the presence of a divalent caution (Mg2+ or Mn2+)7,8.

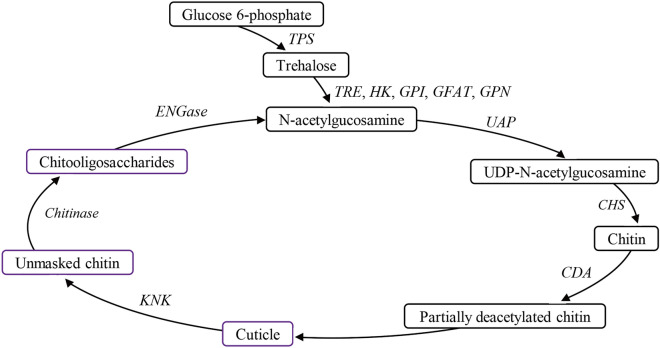

Trehalose is a non-reducing disaccharide in insect hemolymph, which has many functions, such as facilitating carbohydrates absorption and acting as an energy source. It is the major substrate of chitin biosynthesis and also involves in a partial feedback mechanism to regulate feeding behavior and nutrient intake5,7,9,10. The biosynthesis of chitin involves eight enzymes or genes as shown in Fig. 1, such as trehalase (TRE; EC 3.2.1.28), hexokinase (HK), glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), GFAT, glucosamine-6-phosphate-N-acetyltransferase (GPN), phosphoacetyl glucosamine mutase (PGM), UAP, CHS1,7,11. Trehalose is formed by two glucose molecules linked by an α–α bond and widely exists in bacteria, fungi and plants5,9. It is synthesized by trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS; EC 2.4.1.15) and trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP; EC 3.1.3.12) in the fat body of insects, as well as in the integument, trachea, midgut, Malpighian tubule and muscle12–15. It is hydrolyzed by TRE to yield two glucose molecules. TPS, TPP and TRE are important in various physiological processes, such as flight16, resistance to environmental stress17,18, feeding behavior10,19 and chitin synthesis during molting20–22.

Figure 1.

Key enzymes and genes involved in chitin biosynthesis and degradation in A. pisum. TPS, trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene; TRE, trehalase gene; HK, hexokinase gene; GPI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase gene; GFAT, glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotansferasr gene; GPN, glucosamine-6-phosphate-N-acetytransferase gene, UAP; UDP-N-acetyglucosamine pyrophosphorylase gene; CHS, chitin synthase gene, Cht1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, eight chitinase genes; IDGF, imaginal disc growth factor gene; ENGase, endo-β-N-acetylgucosaminidase gene.

TPS is an important enzyme in trehalose synthesis, and regulates the insect physiology and behavior, including survival, molting, pupal metamorphosis and chitin metabolism9,12,14,15,23. Three categories of TPS genes (TPS1, TPS2 and TPS3) have been found in insects24. RNAi of TPS decreased trehalose content and subsequent survival rate, produced three abnormal phenotypes (molting deformities, wing deformities, and molting and wing deformities) and changed the gene expression related to the chitin metabolism in Nilaparvata lugens12,23, Leptinotarsa decemlineata14, Tribolium castaneum25 and Bactrocera minax26. TRE regulates chitin metabolism in insects27,28 and is the first enzyme of trehalose catabolism and chitin biosynthesis7,9,29,30. Previous studies have shown that TREs have two forms, soluble trehalase (TRE1) and membrane-bound trehalase (TRE2), and silencing and/or mutation of TREs resulted in high mortality, abnormal phenotype, low chitin production, decreased food intake and changed expression of genes related to chitin metabolism10,14,31–33. Trehalose accumulation in TRE mutants increased larval mortality and affected intestinal integrity due to reduced chitin synthesis and low feeding rate of Drosophila melanogaster10. RNAi of TRE increased the mortality rate and the number of abnormal phenotypes, and decreased the chitin content of Spodoptera exigua, T. castaneum and L. decemlineata14,31,33. In S. exigua, RNAi of SeTre-1 and SeTre-2 produced three different lethal phenotypes (severe-abnormal, abdomen-abnormal and misshapen-wings), increased mortality rates and reduced the chitin content in the cuticle and midgut. Chen et al. found that the SeTre-1 was highly expressed in the cuticle and Malpighian tubules, while SeTre-2 was predominantly expressed in the tracheae and fat body31. In L. decemlineata, RNAi of LdTRE1a increased the mortality of the larvae and pupae, reduced the food intake and slowed down the growth14. Similarly, knockdown of CHS in T. castaneum decreased the survival and fecundity of the population resulting in lethal phenotype and low chitin content4. In S. exigua, the epithelial walls of the larval trachea expanded uniformly after the knockdown of SeCHS-A34. In Toxoptera citricida, nymphs failed to complete molting and entered the next developmental stage after the suppression of TCiCHS by feeding with plant-mediated dsRNA35. These results confirm that RNAi of TPS and TRE is a potential strategy for improving pest management practices36.

The pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is characterized by the complex life cycle, and displays two body color morphs (red and green) in field populations and each color morph is stable within each parthenogenetic clone37,38. Generally, A. pisum is considered to be one of the main agricultural pests. Damages by the aphids are caused not only by directly feeding on plant phloem sap but also by transmitting plant viruses39. Insecticide treatments remain a convenient way for A. pisum control, but excessively use insecticides has resulted in resistance and resurgence. Therefore, it is necessary to study more effective pest control methods.

In this study, in order to understand the functions of TPS and TRE genes in the chitin metabolic pathway of A. pisum, RNAi technology was used to silence the expression of ApTPS and ApTRE, and RT-qPCR was used to determine the expression level of genes related to chitin biosynthesis and degradation. As shown in Fig. 1, we selected ten chitin biosynthesis genes (ApTRE, ApHK, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApGPN, ApUAP, Apchs-2, ApGP and ApTPS)6, two cuticle synthesis genes (chitin deacetylase gene (ApCDA) and Knickkopf protein gene (ApKNK))40,41 and ten chitin degradation genes (chitinase-like genes1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 genes, imaginal disk growth factor gene (ApIDGF) and endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase gene (ApENGase))42. The phenotypes, chitin content and related mRNA expression levels of these genes were described, and the functions of ApTPS and ApTRE in the chitin metabolic pathway in the red and green morphs of A. pisum were clarified.

Results

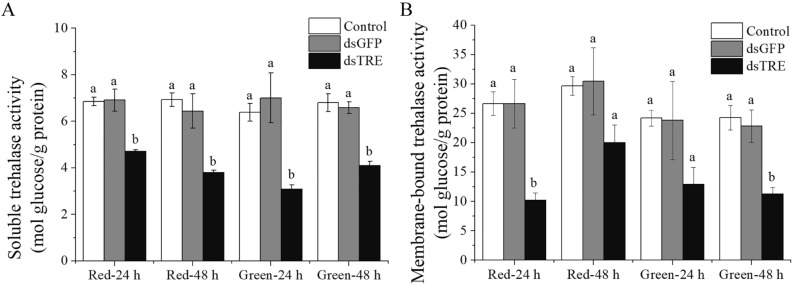

RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE change the activity of trehalase

We measured the activities of soluble trehalase (ApTRE1) and membrane-bound trehalase (ApTRE2) of A. pisum in each dsRNA-injected treatment group and found that the activities of ApTRE1 and ApTRE2 reduced in the dsTRE group compared with control and dsGFP groups (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

The enzyme activity of trehalase at 24 h and 48 h after RNAi. (A) The soluble trehalase activity after RNAi, (B) the membrane-bound trehalase activity after RNAi. Control the normal diet, dsGFP the GFP-dsRNA treatment, dsTPS the TPS-dsRNA treatment, dsTRE the TRE-dsRNA treatment, Red red morphs of A. pisum, Green green morphs of A. pisum. Each bar represents the Means ± SEM from three biological replicates with ten individuals mixed in each replicate. The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The enzyme activity in the artificial diet group was designated as control, and different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

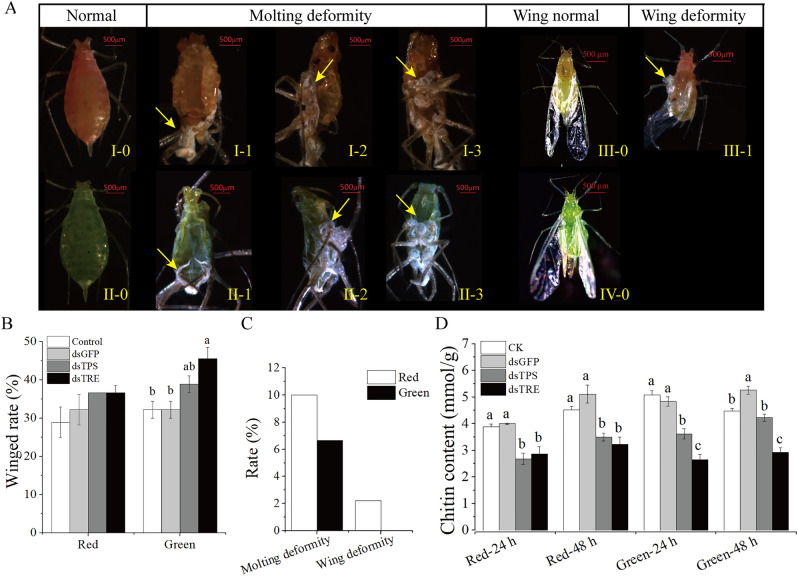

Effects of RNAi on phenotypes and chitin content

As shown in Fig. 3A,B, compared with the control and dsGFP groups, the winged aphid rate was significantly higher in dsTRE of red morphs and dsTPS groups than in the dsTRE group of green morphs (Fig. 3B). The RNAi of ApTRE resulted in two abnormal phenotypes (molting deformity and wing deformity) in the red morphs (Fig. 3A,C), but only one abnormal phenotype (molting deformity) was observed in the green morphs when the molting deformities (the regions indicated by yellow arrows in Fig. 3A, I-1-3 and II-1-3) were compared with healthy aphids (Fig. 3A, I-0 and II-0). Similar effects were observed on wing deformities (the regions indicated by yellow arrow in Fig. 3A, III-1) compared with the normal wing phenotypes (Fig. 3A, III-0 and IV-0). However, no abnormal phenotypes were observed in the control and dsGFP and dsTPS groups. These results are consistent with previous studies that TRE silencing leads to abnormal phenotypes14,31,33, which may relate to the reduction of chitin synthesis.

Figure 3.

Effect of RNAi on phenotype and chitin content. (A) Representative phenotypes of A. pisum after RNAi. I-0 and II-0: normal phenotypes as control phenotype; II-3: abnormal phenotypes in the red morphs, the “molting deformity” phenotype; III-3: abnormal phenotypes in the green morphs, the “molting deformity” phenotype; III-0 and IV-0: normal winged and III-1: abnormal phenotype in the red morphs, the “wing deformity” phenotype. All abnormal insects in the nymph-adult stage were present. (B) The winged rate after RNAi. (C) The abnormal phenotype rates. (D) The chitin content after RNAi. Red, red morphs of A. pisum. Green green morphs of A. pisum, CK the normal diet, dsGFP the GFP-dsRNA treatment, dsTPS the TPS-dsRNA treatment, dsTRE the TRE-dsRNA treatment. Each bar represents the Means ± SEM from three biological replicates with ten individuals mixed in each replicate. The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

We therefore analyzed the chitin content of whole aphids. These results indicated that chitin content decreased in ApTPS and ApTRE RNAi groups compared with control and dsGFP groups in two color morphs (Fig. 3D), but the chitin content significantly increased in the green morphs after dsGFP ingestion at 48 h. Moreover, knockdown of ApTPS reduced the relative chitin content by approximately 4–31% while knockdown ApTRE reduced more by 26–48% relative to those of the control group.

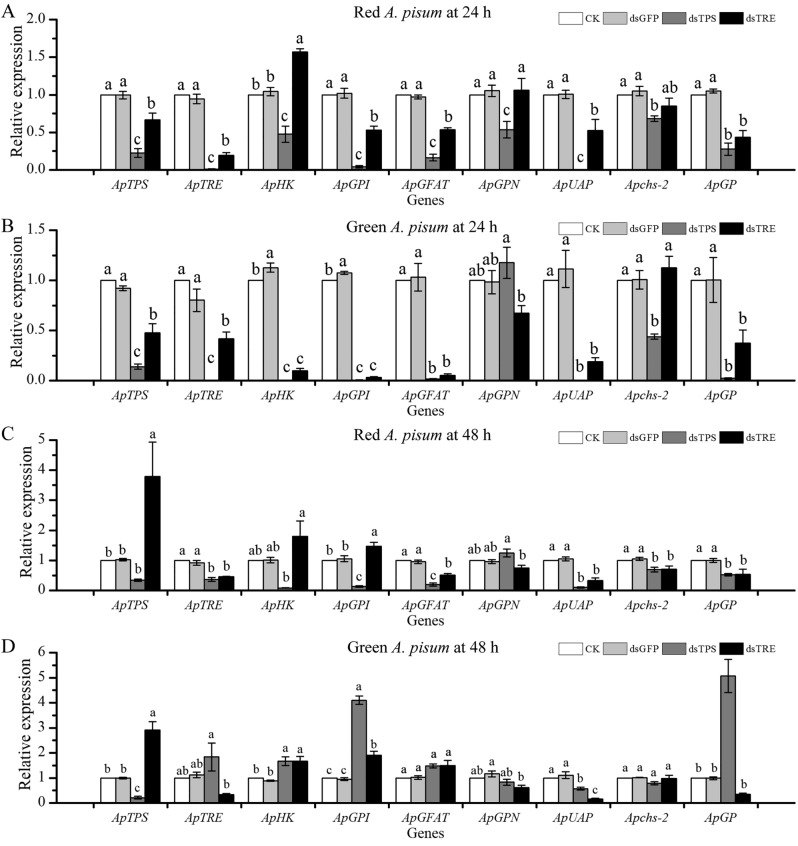

Effect of RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE on the expression of the genes related to chitin biosynthesis pathway

Our results showed that the expression levels of ApTPS and ApTRE were significantly lower in the dsTPS and dsTRE groups than in the control and dsGFP groups (Fig. 4). In addition, RNAi of ApTPS decreased ApTPS expression by approximately 70–80% compared with control groups, and RNAi of ApTRE decreased ApTRE expression by approximately 50–80%. These data suggested that the ApTPS and ApTRE genes were successfully targeted by their dsRNAs and the RNAi technique worked successfully.

Figure 4.

Effect of ApTPS and ApTRE RNAi treatments on the expression of the gens involved in the chitin biosynthesis. (A) in red morphs at 24 h, (B) in green morphs at 24 h, (C) in red morphs at 48 h, (D) in green morphs at 48 h. CK, the normal diet; dsGFP, the GFP-dsRNA treatment; dsTPS, the TPS-dsRNA treatment; dsTRE, the TRE-dsRNA treatment; ApTPS, trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene; ApTRE, trehalase gene; ApHK, Hexokinase gene; ApGPI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase gene; ApGFAT, glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotansferasr gene; ApGPN, glucosamine-6-phosphate-N-acetytransferase gene; ApUAP, UDP-N-acetyglucosamine pyrophosphorylase gene; Apchs-2, chitin synthase gene 2; ApGP, glycogen phosphorylase gene. Each bar represents the Means ± SEM from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The mRNA expression level in the normal artificial diet group was designated as the reference control for the comparisons. The different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

The mRNA expression levels of the chitin biosynthesis pathway-related genes were detected after RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE. As shown in Fig. 4, the expression of chitin biosynthesis-related genes was significantly altered by RNAi of ApTPS. In the red morphs, the expression of ApTRE, ApHK, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApUAP, Apchs-2 and ApGP was significantly down-regulated at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 4A,C). The expression of ApGPN was significantly decreased at 24 h and then significantly increased at 48 h. Similarly, in the green morphs, the expression of ApTRE, ApHK, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApUAP, Apchs-2 and ApGP was significantly down-regulated at 24 h (Fig. 4B,D). The expression of ApHK, ApGPI and ApGP was significantly increased at 48 h, only ApUAP expression was significantly down-regulated at 48 h by RNAi of ApTPS (Fig. 4B,D).

RNAi of ApTRE significantly decreased the expression of ApTPS, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApUAP and ApGP in the red morphs at 24 h (Fig. 4A). There was no difference (P > 0.05) in the expression of ApGPN and Apchs-2 relative to those of the control group. The expression of ApGFAT, ApUAP, Apchs-2 and ApGP was decreased significantly; the expression of ApTPS and ApGPI was increased significantly in the red morphs at 48 h (Fig. 4C), but there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the expression of ApHK and ApGPN relative to those of the control group. The expression of ApTPS, ApHK, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApUAP and ApGP was decreased significantly in the green morphs at 24 h (Fig. 4B), but there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the expression of ApGPN and Apchs-2. However, the expression of ApGPN, ApUAP, Apchs-2 and ApGP was decreased, and the expression of ApTPS, ApHK, ApGPI and ApGFAT was increased at 48 h (Fig. 4D).

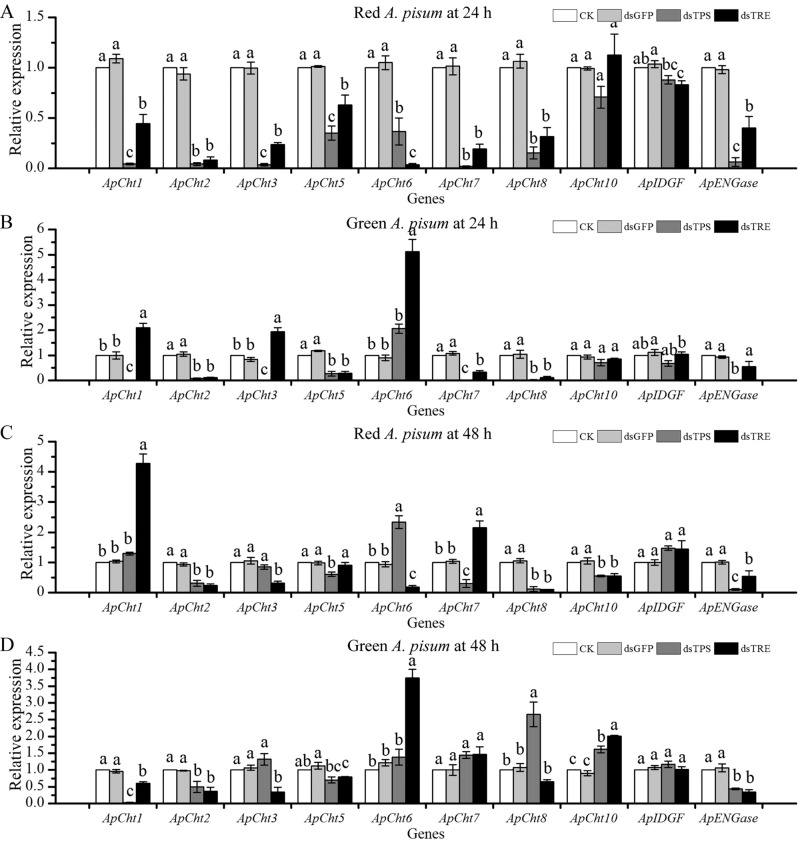

Effect of RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE on chitinase and chitinase-like genes expression

The mRNA expression levels of chitinase and chitinase-like genes were detected after RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE (Fig. 5). RNAi of ApTPS decreased the expression of chitinase and chitinase-like genes in the red morphs at 24 h (Fig. 5A). In the red morphs, the expression of ApCht1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 and ApENGase was significantly decreased at 48 h (Fig. 5C), but the expression of ApCht1, 6 and ApIDGF was increased. In the green morphs, the expression of ApCht1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, ApIDGF and ApENGase was decreased at 24 h (Fig. 5B). However, the expression of ApCht1, 2, 5 and ApENGase was significantly decreased at 48 h (Fig. 5D), but the expression of ApCht6, 7, 8, 10 and ApIDGF was increased.

Figure 5.

Effects of RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE on relative expression of the chitinase and chitinase-like genes. (A) In red morphs at 24 h, (B) in green morphs at 24 h, (C) in red morphs at 48 h, (D) in green morphs at 48 h. CK, the normal diet; dsGFP, the GFP-dsRNA treatment; dsTPS, the TPS-dsRNA treatment; dsTRE, the TRE-dsRNA treatment; ApCht1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10; ApIDGF, Imaginal disc growth factor gene; ApENGase, Endo-β-N-acetylgucosaminidase gene. Each bar represents the Means ± SEM from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The mRNA expression level in the normal artificial diet group was designated as the reference control for the comparisons. The different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

RNAi of ApTRE significantly down-regulated the expression of ApCht2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10 and ApENGase in the red morphs at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 5A,C). The expression of ApCht1 and ApCht7 was decreased significantly at 24 h, and then significantly increased at 48 h (Fig. 5A,C). The expression of the ApCht2, 5, 7, 8 and ApENGase was decreased significantly in the green morphs at 24 h (Fig. 5B), but the expression of the ApCht1, 3 and 6 was significantly increased. The expression of ApCht1, 2, 3, 5, 8 and ApENGase was decreased significantly at 48 h (Fig. 5B), but the expression of ApCht6 and ApCht10 was increased (Fig. 5D). There was no difference (P > 0.05) in the expression of ApCht6 and ApIDGF between 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5B,D).

Discussion

In our study, two abnormal phenotypes (molting deformities and wing deformities) were found in the aphid morphs after RNAi of ApTRE (Fig. 3A). However, no abnormal phenotypes were observed in the dsTPS, dsGFP and control groups. These abnormal phenotypes might be due to the remarkable decrease of chitin content (Fig. 3D), and in the dsTPS group the reduction of chitin synthesis did not reach the threshold for abnormal deformity. The abnormal phenotype rates are only 10% (Fig. 3C) considering that most of the genes were significantly changed by the RNAi of ApTRE. There seem some differences in the abnormal phenotype rates among insect species. It is reported that the silencing of TPS resulted in abnormal phenotypes in L. decemlineata14, B. minax26 and N. lugens12. Interestingly, the rates of molting and wing deformities were all less than 10% by RNAi of TRE, but the abnormal phenotypes rates were higher in T. castaneum33, S. exigua31 and L. decemlineata14.

The manipulation of chitin affected the growth and development of insects in previous studies31,43–46. Such as, suppression of CHS decreased the survival, fecundity, egg hatching ability and the number of insects molting46. Besides ApTPS and ApTRE suppression decreased and increased the content of trehalose (data not shown), respectively. It was reported that trehalose content affected the survival and feed behavior of insects14,15,24,31. Trehalose is known to be a precursor of chitin synthesis and would affect the chitin biosynthesis pathway. Our results showed that RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE down-regulated the expression levels of chitin biosynthesis-related genes (Fig. 4A,B) as reported in N. lugens12 and T. castaneum25,33. In contrast, in the N. lugens, the expression of NlGFAT, NlGNPNA and NlUAP was significantly increased by knockdown of two NlTPS12. These differences may be due to differences between the species genome. We also found that the expression of glycogen phosphorylase (ApGP) significantly decreased after RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE (Fig. 4) as in N. lugens13, supporting previous studies that ApTPS and ApTRE also regulate chitin synthesis by influence the expression of glycogen phosphorylase (GP) and glycogen synthase (GS) genes because insects must accumulate glycogen before entering diapause33,47,48. Thus, RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE may enhance glycolysis by activating glycogen phosphorylase and then influence glycogen metabolism. Our results showed that the silencing of ApTPS and ApTRE altered the expression levels of chitin degradation-related genes (Fig. 5), similar results were shown in N. lugens12,49, and thus influence aphid development as other studies showed that chitin-degrading enzymes play an important role in growth and development, especially during larval molt and pupation1,15.

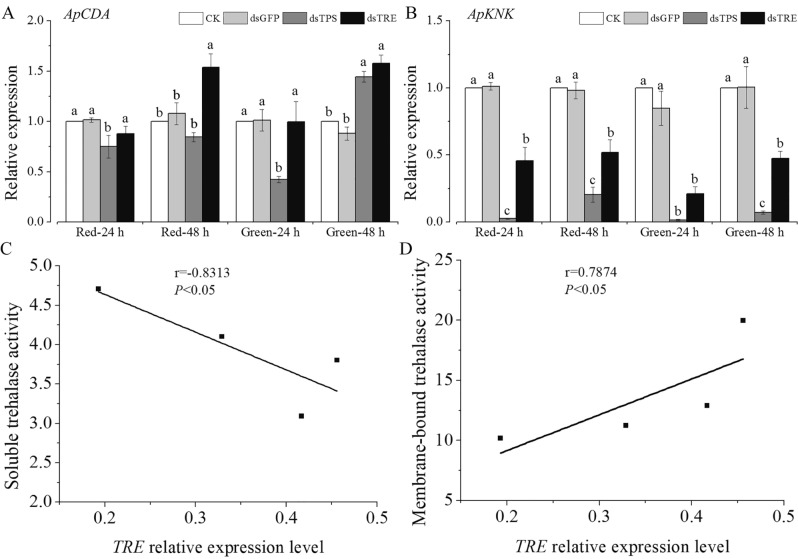

Chitin deacetylase (CDA) is found in the cuticles and peritrophic matrix of insects. It is conceivable that partial deacetylation may render matrix chitin more resistant to hydrolysis by endochitinases6. Our results showed that RNAi of ApTPS inhibited ApCDA expression in the red and green morphs at 24 h, but promoted ApCDA expression in the green morphs at 48 h (Fig. 6A). The expression of ApCDA was also promoted by RNAi of ApTRE at 48 h (Fig. 6A). In addition, the Knickkopf protein (KNK) is a cuticular protein that protects chitin from chitinases and organizes it into laminae40. In our study, we showed that the ApKNK expression significantly decreased after RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE (Fig. 6B). Previous studies have demonstrated that knockout of SpCDA1 and TcKNK increased molting difficulty and cause high larval mortality in Stegobium paniceum and T. castaneum6,40,41,50. Interestingly, the expression of ApCDA1 and ApKNK at 48 h was significantly higher compared with those at 24 h (Fig. 6A,B), which may be a feedback regulation between lower chitin content and the up-regulated expression of chitin metabolism-related genes (Figs. 4D and 5D). The enzyme activities of ApCDA and ApKNK were increased for protective cuticle degradation. We also found that the expression of some chitinase and chitinase-like genes were restored and even enhanced at 48 h. Interestingly, Yang et al. also found similarity trends at 72 h after RNAi of TPS21. In addition, the increase in the expression, restoration and enhancement of the chitin synthesis-related genes ApTPS, ApHK and ApGPI by RNAi of ApTRE (Fig. 4C,D) may be a possible feedback mechanism to improve stress resistance, protect cellular structures and present extensive gene duplication51–53, accelerating the degradation of old cuticle to provide precursor for the synthesis of new cuticle as Fig. 1 shows. Figure 6C, D showed there was a negative correlation of the ApTRE expression level with the activity of ApTRE1 (Fig. 6C; r = − 0.8313, P < 0.05), and a positive correlation with the activity of ApTRE2 (Fig. 6D; r = 0.7874, P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The expression levels of ApCDA and ApKNK at 24 h and 48 h after RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE. (A) Chitin deacetylase gene, (B) Chitin-binding protein Knickkopf gene, (C, D) The correlation analyses between the trehalase activity and the expression of ApTRE. Each point in the figure represents a sample, and the P-values and the correlation coefficient r are presented. Bivariate correlations between variables were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. CK, the normal diet; dsGFP, the GFP-dsRNA treatment; dsTPS, the TPS-dsRNA treatment; dsTRE, the TRE-dsRNA treatment. Each bar represents the Means ± SEM from three biological replicates and three technical replicates and the data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer test. The mRNA expression level in the artificial diet group was designated as control, different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

We found five ApTRE gene isomers (XM_001950229.4, XM_003245847.4, XM_016808594.2, XM_003247977.3 and XM_029491831.1) and two ApTPS gene isomers (XM_003244776.4 and XM_001943581.5) from the aphid genome (Supplementary Fig. 1). RNAi experiments of ApTRE reduced trehalase activities (Fig. 2), suggesting there is no compensation between isomers in A. pisum as reported in Nilaparvata27. Our ApTRE primer sequences match 100% to two of five ApTRE isomers (XM_001950229.4 and XM_003245847.4) and 70% to other three ApTRE isomers (XM_016808594.2; XM_003247977.3 and XM_029491831.1). The comparison between the sequence of the PCR product using our primer sequences with these gene sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2) suggested that under our PCR condition all gene copies could be amplified. The RT-qPCR results and the activity of trehalases after RNAi reflect a total gene expression and enzymatic activities (Fig. 2). Bansal et al. by phylogenetic analysis suggestion the ApTRE gene (XM_001950229.4) was soluble trehalase54. It is not clear whether XM_003245847.4 could be a membrane-bound form.

We found some different effects of RNAi of ApTPS and ApTRE on the expression of chitin metabolism-related genes between red and green morphs (Figs. 4 and 5). Two diagrammatic representations, related to insect chitin biosynthesis and degradation pathways, are drafted in Supplementary Fig. 5 for the 48 h expression data, and Supplementary Table 3 for the 24 h data. The figure also summarizes the differences between red and green morphs. Such as, RNAi of ApTRE increased ApHK expression in the red morphs at 24 h, but decreased by 90% in the green morphs (Fig. 4A,B). This difference might show color polymorphism of A. pisum, and may be related to local adaptation and ecological speciation55. In addition, in the green morphs, the content of chitin at 48 h (Fig. 3D) and the expression of ApHK and ApGPI at 24 h (Fig. 4B) were significantly higher in the dsGFP group than in the control group. This may be due to the metabolic disorder induced by the deleterious substances in artificial diet. It has been found that the artificial diet influenced the growth, development and reproduction56.

RNAi technology is a promising mean to study gene function and could be used as a novel control strategy for agricultural crop pests. Silencing of ApTPS and ApTRE affects the growth and development of the aphids and proves that trehalose plays a vital role in chitin metabolism and aphid phenotypes. These results can deepen our understanding of the biological functions of ApTPS and ApTRE in A. pisum, lay a foundation for a better understanding into the molecular mechanisms of insect metamorphosis, and potentially using them as candidate genes in agricultural pest management.

Materials and methods

Insect and culture conditions

Clones of red and green morphs of A. pisum were established from single virginiparous females. They were collected in 2017 from the same plant of M. sativa in Lanzhou, China, and were reared on the fava bean Vicia faba. All plants and aphid cultures were reared at 20 ± 1 °C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, with a photoperiod of 16 h L:8 h D. Mature aphids were put on a fava bean leaf for 12 h and the resulting neonate nymphs, 0–12 h old, were used throughout the experiment.

RNA isolation and first-strand cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated using TRizol reagent (BBI Life Sciences, Shanghai, China) following manufacturer’s instructions. The total quantities of extracted RNA were assessed using a micro-volume UV spectrophotometer (Quawell Q5000, Quawell, USA). The RNA integrity was further confirmed by 1% formaldehyde agarose gel electrophoresis. Total RNA was dissolved in 50 μL DEPC-water and stored at − 80 °C. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China), stored at − 20 °C and used for subsequent experiments.

Cloning of TPS and TRE cDNAs

The primer sets, TPS-F/R and TRE-F/R, used for cloning of ApTPS and ApTRE were designed using the primer software Primer 5.0 (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA) based on the TPS gene sequence (GENBANK accession: XM_001943581.5), and the TRE gene sequence (GENBANK accession: XM_003245847.4) of the A. pisum. The primers for the Green Fluorescent Protein (pET28a-EGFP, miaolingbio, Wuhan, China) was referenced in Yang21. All sequences of these primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The component of the PCR mixture included 1.0 μL of the template (1 ng/μL), 12.5 μL 2 × Power Tap PCR MasterMix (BioTeke, Beijing, China), 1.0 μL of each primer (10 μmol/μL), and 9.5 μL Rnase-free H2O for a final volume of 20 μL. The PCR conditions were pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 95 °C for 45 s, at 55 °C for 45 s and at 72 °C for 1 min, then 10 min at 72 °C for a final extension. The PCR products were subjected to 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and purified by the DNA gel extraction kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China). The purified PCR product was ligated into the pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and sequenced by Tsing Ke Biological Technology (Tsing Ke Biological Technology, Beijing, China) using the dideoxynucleotide method. The lengths of the resulting ApTPS, ApTRE, and GFP genes were 421 bp, 416 bp, and 688 bp, respectively. Next, we aligned five ApTRE isomers and two ApTPS isomers with our primers and the sequences of the PCR products (Supplementary Fig. 1), respectively.

dsRNA synthesis and feeding

Three pairs of primers (dsTPS-F/R, dsTRE-F/R and dsGFP-F/R), with the T7 RNA promoter sequence flanking at the 5′-end of each gene, were designed and synthesized (Supplementary Table 1) and used to make the templates for in vitro dsRNA transcription via PCR. The dsRNAs were synthesized using the TranscriptAid T7 High Yield Transcription Kit (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol41. The size of the dsRNA products was confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and the content was assessed using a micro-volume UV spectrophotometer.

The artificial diet was made according to the following procedures of previous studies57,58 with sucrose (845 mM), l-amino acids, Vitamins and others. The l-amino acids (mM) include Ala (20.06), β-Ala (0.70), Asn (14.06), Asp (19.88), Cys (2.44), Glu (10.15), Gln (30.49), Gly (22.19), His (6.94), Leu (20.06), Lys (19.22), Met (4.85), Orn (0.56), Phe (10.29), Pro (11.23), Ser (11.83), Thr (10.67), Try (2.09), Tyr (2.13) and Val (16.29). The vitamins (mg/100 mL) include p-aminobenzoic acid (10), l-ascorbic (100), biotin (0.1), d-calcium pantothenate (5), choline chloride (50), folic acid (1), I-inositol (42), nicotinamide (10), pyridoxin HCl (2.5), riboflavin (0.5) and thiamine di-HCl (2.5). Other components (mg/100 mL) are CuSO4·5H2O (0.47), FeCl3·6H2O (4.45), MnCl2·4H2O (0.65), NaCl (2.54), ZnCl2 (0.83), calcium citrate (10), cholesteryl benzoate (2.5), MgSO4·7H2O (242) and KH2PO4 (250). The diet was filtered through a 2 μm membrane, dispensed in 1.0 mL aliquots, and stored at − 20 °C before the artificial diet feeding assay.

Glass vials (2.5 cm in diameter) were sterilized and used for the aphid artificial double-membrane feeding assay. Briefly, one opening of glass vials was completely sealed with parafilm. A given volume of test samples containing either nuclease-free water or dsRNA was added to the 1.0 mL artificial diet for a final concentration of 400 ng/μL. Seventy microliters of the artificial diet with either dsTPS, dsTRE, or dsGFP were sandwiched between two layers of the parafilm membrane58.

Fifteen 3-day-old aphids were introduced into one vial with a fine paintbrush. Then, another vial with the diet sandwich was closed with the aphid containing vial by a piece of sterilized gauze. The control group was only fed with the artificial diet without dsRNA. The artificial diet was replaced every other day to prevent dsRNA degradation. After 4 days, all surviving morphs from each treatment were selected and divided randomly into three replicates groups, and then transferred to fresh bean leaf discs. The collections were done at 24 h and 48 h after feeding on plant to alleviate the adverse effects of the artificial diet on treated aphids and allow the aphids to adapt feeding on the plants. Previous studies have shown that RNAi effects can be remained from the parents subjected to RNAi in their progenies59. Abdellater et al. found that RNAi had a prolonged impact and remained significantly effective in the six subsequent generations60. Mutti et al. also found that Coo2 (Salivary gland transcript) expression dropped dramatically in 3 days after injection with dsRNA61.

Phenotype observations

Phenotypes of 30 wingless aphids in each treatment group were observed and analyzed after the RNAi treatments every 12 h until they became adults and began to produce young nymphs. Three replicates were set for each treatment.

Trehalase activity assay

Insects were subjected to soluble and membrane-bound trehalase activity analyses at 24 h and 48 h after the 4-day RNAi treatment. Trehalase activity was assayed according to the method described by Shen et al.22, with some modifications. Briefly, ten aphids were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 130 mM NaCl; 7 mM Na2HPO4·2H2O; 3 mM NaH2PO4·2H2O; pH 7.0), then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 20 min at 4 ℃. Subsequently, 450 μL of the supernatant was centrifuged again at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 ℃. After superspeed centrifugation, the supernatant was directly used to determine the soluble TRE activity and protein content, while the sediment was re-suspended in PBS to evaluate the membrane-bound TRE activity and protein content. The measurement of trehalase activities was based on the rate of glucose released from trehalose. Either the supernatant (TRE1 activity) or the suspension (TRE2 activity) obtained from ultracentrifugation (70 μL) was uniformly mixed with 40 μL of 40 mM trehalose (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and 180 μL of PBS. The mixture was then incubated at 37 ℃ for 60 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4℃. The resulting supernatant (20 μL) was used to determine the TRE1 and TRE2 activities using the glucose assay kit (Solarbio Biochemical Assay Division, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Three replicates were set for each RNAi treatment and the control.

Measurements of chitin content in RNAi aphids

Ten individuals were homogenized with 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4·2H2O, 3 mM NaH2PO4·2H2O; pH 7.0). The total chitin was extracted from the aphid body and analyzed according to the method described by Xia and Shen62 with sight modifications. Briefly, the homogenate was centrifuged at 1800 × g for 15 min at 25 ℃. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was suspended in 400 μL of 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), centrifuged at 1800 × g for 5 min at 100 ℃, and then centrifuged again at 1800 × g for 10 min at 25 ℃. To deacetylate chitin, the pellet was redissolved in 0.3 mL of KOH (14 mol/L) and incubated in dry baker at 130 ℃ for 1 h. Celite and different concentrations of absolute alcohol were added to the samples to obtain the insoluble chitosan. 100 μL of chitosan extract solution, 50 μL of 10% KHSO4 and 50 μL of 10% NaNO2 were mixed and incubated at 25 ℃ for 15 min to deaminate the glucosamine residues and depolymerize the chitosan. After the incubation with 40 μL of 12.5% NH4SO3NH2 at 25 ℃ for 15 min, 40 μL of 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolone hydrazone hydrochloride hydrate (MBTH, 5 g/L) was mixed and incubated at 25℃ for 5 min. Then, 40 μL of 0.83% FeCl3 was added and incubated at 25 ℃ for 10 min. Finally, the chitin content was measured in a 96-well micro plate in a total reaction volume of 160 μL for each sample per micro-plate well. Changes of absorbance were measured under 650 nm in a micro plate spectrophotometer (Bio Tek ELX800UV, Winsooski, VT, USA). A control reaction treated with double distilled water was included for comparison. The chitin content was calculated based on the established standard concentration curve of d-(+)-Glucosamine HCl (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Three replicates were set for each treatment.

Quantification of mRNA expression levels

Aphids were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was isolated from seven whole aphids. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China). The RT-qPCR analysis was carried out in 96-well 0.1-mL Block plates using a QuantStudio™ 5 system (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Each reaction contained 1.0 μL of the template (1 ng/μL), 10.0 μL of 2 × Plus SYBR real-time PCR mixture (BioTeke, Beijing, China), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μmol/μL), 8 μL of EDPC-ddH2O, and 0.5 μL of 50 × ROX Reference Dye in a final volume of 20 μL. The RT-qPCR condition was pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, and then 40 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s and at 55–62 °C for 30 s. After each reaction, a melting curve analysis (denatured at 95 °C for 15 s, annealed at 60 °C for 1 min, and denatured at 95 °C for 15 s) was conducted to ensure consistency and specificity of the amplified product. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were set in the RT-qPCR analyses for each treatment. Quantification of the transcript level was conducted according to the method63. The RT-qPCR primers of chitin metabolism-related genes were designed to determine the expression of the corresponding homologous genes, including ApTRE, ApHK, ApGPI, ApGFAT, ApGPN, ApUAP, Apchs-2, ApGP, ApTPS, ApCht1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, ApIDGF, ApENGase, ApCDA and ApKNK, and the ribosomal protein L27 gene (rpL27) was used as the reference gene61 (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

The enzyme activity, abnormal phenotype rates, mRNA expression level and chitin content of the aphids fed with in the normal artificial diet without dsRNAs were designated as control. All data were represented as Means ± SEM of three replicates per each treatment and analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey–Kramer test. Bivariate correlations between variables were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 19.0, Origin 8.5. Excel 2010 were used to construct the histograms. The different letters indicate a significant difference in mRNA levels between the artificial diet group (CK) and the dsRNA-ingested group measured simultaneously. The down/up-regulation of the genes related to chitin metabolism at 24 h after the RNAi treatments were showed in Supplementary Table 3.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31960351, 31660522) and the Discipline Construction Fund Project of Gansu Agricultural University (GAU-XKJS-2018-149).

Author contributions

G.W. and S.G. carried out the experiments, participated in data analysis; Y.G. and C.L. carried out the statistical analyses; G.W., J.-J.Z. and C.L. designed the study; G.W., Y.G. and J.-J.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-80277-2.

References

- 1.Merzendorfer H, Zimoch L. Chitin metabolism in insects: Structure, function and regulation of chitin synthases and chitinases. J. Exp. Biol. 2003;206:4393–4412. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelkenberg M, et al. Chitin is a necessary component to maintain the barrier function of the peritrophic matrix in the insect midgut. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;56:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muthukrishnan, S. et al. Chitin metabolism in insects. Insect. Mol. Biol. Biochem193, 235. 10.1016/B0-44-451924-6/00051-X (2012).

- 4.Arakane Y, et al. Chitin synthases are required for survival, fecundity and egg hatch in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;38:959–962. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbein AD, et al. New insights on trehalose: A multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology. 2003;13:17R–27R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu KY, et al. Biosynthesis, turnover, and functions of chitin in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016;61:177–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer KJ, Koga D. Insect chitin: Physical state, synthesis, degradation and metabolic regulation ☆. Insect. Biochem. 1986;16:851–877. doi: 10.1016/0020-1790(86)90059-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merz RA, et al. E. Biochemistry of chitin synthase. EXS. 1999;87:9–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8757-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla E, et al. Insect trehalase: Physiological significance and potential applications. Glycobiology. 2015;25:357–367. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasugi T, Yamada T, Nishimura T. Adaptation to dietary conditions by trehalose metabolism in Drosophila. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1619. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01754-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen E. Chitin synthesis and inhibition: A revisit. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010;57:946–950. doi: 10.1002/ps.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, et al. Knockdown of two trehalose-6-phosphate synthases severely affects chitin metabolism gene expression in the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017;73:206. doi: 10.1002/ps.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, et al. Glycogen phosphorylase and glycogen synthase: Gene cloning and expression analysis reveal their role in trehalose metabolism in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) J. Insect. Sci. 2017;17–42:1–11. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iex015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi JF, et al. Physiological roles of trehalose in Leptinotarsa larvae revealed by RNA interference of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and trehalase genes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;77:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda H, et al. Flies without trehalose. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:1244–1255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clegg JS, Evans DR. Blood trehalose and flight metabolism in the blowfly. Science. 1961;134:54–55. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3471.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambhod C, et al. Energy metabolites mediated cross-protection to heat, drought and starvation induced plastic responses in tropical D. ananassae of wet-dry seasons. BioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/158634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, et al. Metabolism and cold tolerance of Chinese white pine beetle Dendroctonus armandi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) during the overwintering period. Agric. Forest Entomol. 2017;19:10–22. doi: 10.1111/afe.12176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson SN, Redak RA. Interactions of dietary protein and carbohydrate determine blood sugar level and regulate nutrient selection in the insect Manduca sexta L. BBA-Gen Subj. 2000;1523:91–102. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Candy DJ, Kilby BA. Studies on chitin synthesis in the desert Locust. J. Exp. Biol. 1962;39:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang M. M. Regulating effects of trehalase and it inhibitor (Validamycin) on the trehalose and chitin metabolism in Nilaparvata lugens. (Hangzhou Normal University, 2016). (in Chinese).

- 22.Shen QD, et al. Excess trehalose and glucose affects chitin metabolism in brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017;20:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2017.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, et al. Feeding-based RNA interference of a trehalose phosphate synthase gene in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Insect. Mol. Biol. 2010;19:777–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang B, et al. Invertebrate trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene: Genetic architecture, biochemistry, physiological function, and potential applications. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:30. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, Q. W., Jin, S. & Zhang, L. Regulatory functions of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase in the chitin biosynthesis pathway in Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) revealed by RNA interference. B. Entomol. Res.108, 388–399 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Xiong KC, et al. RNA interference of a trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene reveals its roles during larval-pupal metamorphosis in Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae) J. Insect Physiol. 2016;91–92:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao L, et al. Functional characterization of three trehalase genes regulating the chitin metabolism pathway in rice brown planthopper using RNA interference. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27841. doi: 10.1038/srep27841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, et al. Study on the effect of wing bud chitin metabolism and its developmental network genes in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, by Knockdown of TRE gene. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:750. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker A, et al. The regulation of trehalose metabolism in insects. Experientia. 1996;52:433–439. doi: 10.1007/BF01919312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang B, et al. Trehalase in Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Effects on beetle locomotory activity and the correlation with trehalose metabolism under starvation conditions. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2014;49:255–264. doi: 10.1007/s13355-014-0244-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, et al. Different functions of the insect soluble and membrane-bound trehalose genes in chitin biosynthesis revealed by RNA interference. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao, L. N. Regulating effects of trehalase and TPS on the key genes in the pathway of trehalose metabolic in Nilaparvata lugens. (Hangzhou Normal Univiversity, 2014). (in Chinese).

- 33.Tang B, et al. Knockdown of five trehalase genes using RNA interference regulates the gene expression of the chitin biosynthesis pathway in Tribolium castaneum. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16:67. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X, et al. Disruption of Spodoptera exigua larval development by silencing chitin synthase gene A with RNA interference. B. Entomol. Res. 2008;98:613–619. doi: 10.1017/S0007485308005932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang F, et al. Identification, characterization and functional analysis of a chitin synthase gene in the brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida (Hemiptera, Aphididae) Insect. Mol. Biol. 2016;25:422–430. doi: 10.1111/imb.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu XD, et al. RNAi-mediated plant protection against aphids. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016;72:1090–1098. doi: 10.1002/ps.4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, et al. A small set of differentially expressed genes was associated with two color morphs in natural populations of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Gene. 2018;651:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuchida T, et al. Symbiotic bacterium modifies aphid body color. Ence. 2010;330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu X, et al. Engineering plants for aphid resistance: Current status and future perspectives. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014;127:2065–2083. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaudhari SS, et al. Knickkopf protein protects and organizes chitin in the newly synthesized insect exoskeleton. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17028–17033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112288108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang WJ, et al. Functional characterization of chitin deacetylase 1 gene disrupting larval-pupal transition in the drugstore beetle using RNA interference. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B. 2018;219–220:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakabachi A, Shigenobu S, Miyagishima S. Chitinase-like proteins encoded in the genome of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect. Mol. Biol. 2010;19:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu QS, Arakane Y, Beeman RW, et al. Functional specialization among insect chitinase family genes revealed by RNA interference. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6650–6655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800739105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, D. Q. The functions of chitinase genes from Locusta migratoria. (Shanxi University, 2011) (in Chinese).

- 45.Xia, W. K. Study on Important genes in the biosynthetic and metabolic pathways of chitin in Panonychus citri. (Southwest University, 2015). (in Chinese).

- 46.Zhao Y, et al. Plant-mediated RNAi of grain aphid CHS1 gene confers common wheat resistance against aphids. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:2754–2760. doi: 10.1002/ps.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pullin AS. Physiological relationships between insect diapause and cold tolerance: Coevolution or coincidence. Eur. J. Entomol. 1996;93:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren XY, et al. Metabolic adaption and evaluation of cold hardiness on diapausing ladybird, Coccinella septempunctata L. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015;37:1195–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang B, et al. Suppressing the activity of trehalase with validamycin disrupts the trehalose and chitin biosynthesis pathways in the rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2017;137:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tetreau G, et al. Overview of chitin metabolism enzymes in Manduca sexta: Identification, domain organization, phylogenetic analysis and gene expression. Insect Biochem. Mol. 2015;62:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen QF, et al. Role of trehalose phosphate synthase in anoxia tolerance and development in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3274–3279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh V, et al. TREHALOSE PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE11-dependent trehalose metabolism promotes Arabidopsis thaliana defense against the phloem-feeding insect Myzus persicae. Plant J. 2011;68:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richards S, et al. Genome sequence of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bansal R, et al. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of soluble trehalase gene in Aphis glycines, a migratory pest of soybean. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2013;103:286–295. doi: 10.1017/S0007485312000697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L, et al. A small set of differentially expressed genes was associated with two color morphs in natural populations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Gene. 2018;651:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sutherland ORW, et al. Sexual forms of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, produced on an artificial diet. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1969;12:240–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1969.tb02520.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Febvay G, et al. Influence of the amino acid balance on the improvement of an artificial diet for a biotype of Acyrthosiphon pisum (Homoptera: Aphididae) Can. J. Zool. 1988;66:2449–2453. doi: 10.1139/z88-362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sapountzis P, et al. New insight into the RNA interference response against cathepsin-l gene in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum: Molting or gut phenotypes specifically induced by injection or feeding treatments. Insect. Biochem. Mol. 2014;51:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bucher G, et al. Parental RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera) Curr. Biol. 2002;12:R85–R86. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdellatef E, et al. Silencing the expression of the salivary sheath protein causes transgenerational feeding suppression in the aphid Sitobion avenae. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:849–857. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mutti NS, et al. RNAi knockdown of a salivary transcript leading to lethality in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect. Sci. 2006;6:1–7. doi: 10.1673/031.006.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xia WK, et al. Functional analysis of a chitinase gene during the larval-nymph transition in Panonychus citri by RNA interference. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2016;70:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10493-016-0063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.