Highlights

-

•

Vaginal agenesis is a complex pediatric condition that lead to long-term urinary, gastrointestinal, and sexual dysfunction.

-

•

A meticulous physical examination and in-depth diagnostic investigations are necessary to determine the appropriate surgical management.

-

•

Reconstruction of neovagina can be retrieved from the ileum.

Abbreviations: ARM, anorectal malformations; ARVF, anorectovaginal fistula; ASARP, anterior sagittal anorectoplasy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; MRKH, Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser; MURCS, Müllerian duct aplasia, renal aplasia, and cervicothoracic somite dysplasia; PSARP, Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty; VACTERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac malformations, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb anomalies syndrome

Keywords: Vaginal agenesis, Anorectal malformation, MRKH syndrome

Abstract

Vaginal agenesis with anorectal malformations is a complex pediatric condition that adversely affects various physiological processes in the body. It may cause disturbances in defecation and urination, abnormalities in the urinary and gastrointestinal tract, dysfunction of the genital and reproductive organs, and sexual function disorders. The complexity in the surgical management of vaginal agenesis includes the selection of a functional reconstruction technique for anal and vaginal formation, timing of the reconstruction, and management of complications in the associated organ system.

Herein, we describe a patient with Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome accompanied by a rectovesical fistula. Other abnormalities, such as microcephaly, polydactyly, long urethral abnormalities resembling the male urethra, and complications in the kidney and urinary tract, were observed in the patient. The associated complications included recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary overflow incontinence, vesicoureteric reflux, hydroureter, and left renal hydronephrosis. The patient underwent posterior sagittal anorectoplasty surgery and vaginal reconstruction. The long-term vaginal physiological development of patients with this condition remains unknown.

1. Introduction and importance

Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a collection of several congenital defects in the female reproductive system, including congenital agenesis of the uterus, cervix, and upper two-thirds of the vagina [1,2]. The incidence of this rare condition remains unknown. Studies have shown that the incidence of congenital uterine and vaginal agenesis in MRKH syndrome was one in 4000–5000 female births [3,4].

This syndrome causes anatomical and functional disorders in the reproductive organs that have the potential to significantly impact various aspects of life [4,5]. Thus, the management, treatment methods, and time to provide the treatments need to be considered to reduce the impact that this condition may have on physiological processes in the future.

MRKH syndrome associated with anorectal malformations (ARM) is a very complex pediatric surgical case because it involves the maintenance of the anatomical, functional, and medical outputs of the vagina and anus. The main challenge in the management of this condition is the successful reconstruction of a vital and functional artificial vagina and anus [6]. Apart from the surgical technique, the timing of the reconstructive surgery in this patient is still a matter of debate. Herein, we present a complex and very rare case of MRKH syndrome associated with ARM and various other congenital defects.

2. Case presentation

We reported a case of a 15-month-old girl who presented to our hospital with complaints of urinating and defecating out of the same hole since birth [7]. Informed consent was obtained from parent’s subject to report this case. The patient was a full-term baby born via cesarean section with a birth weight of 2700 g and an Apgar score of 9/10. Genetic examinations showed a 46XX karyotype. No other congenital abnormality was noted. The patient was previously diagnosed with a cloaca and had undergone loop transverse colostomy at the age of 1 month.

A preoperative physical examination of the abdomen revealed a transverse colostomy with vital impressions. Anogenital examinations revealed the presence of clitoromegaly with only one hole in the perineal region (Fig. 1). The anal canal was not detected; however, separate anus and vaginal cavities were observed. Fistulographic examination showed a high-lying ARM with rectovesical fistula, left hydronephrosis, and a hydroureter.

Fig. 1.

Clinical picture showing the presence of clitoromegaly and a vaginal cavity without an opening.

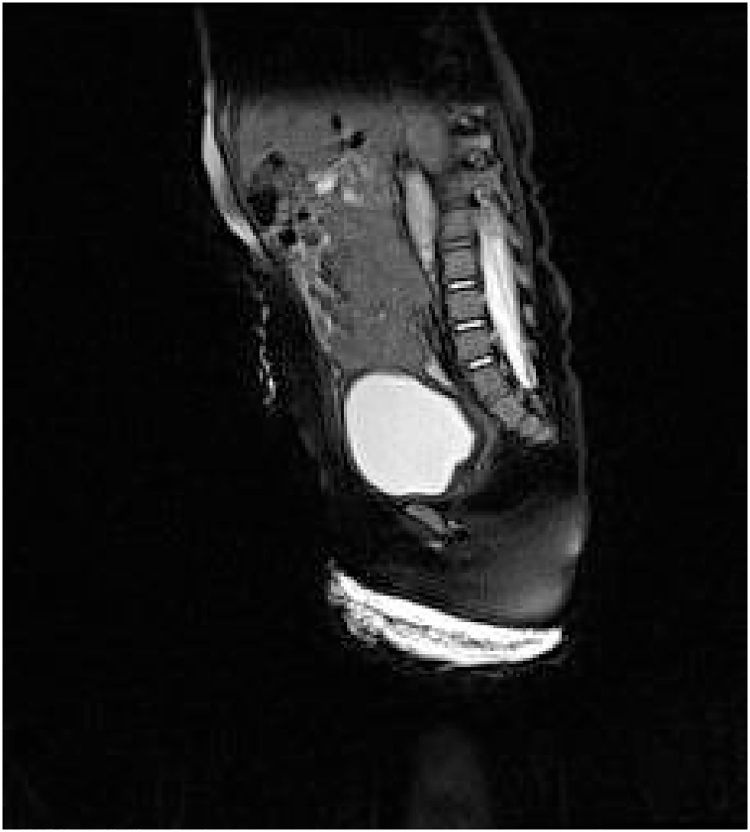

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvic region showed that the vaginal structure on the posterior bladder coincided with the rectum (Fig. 2). In addition, tubular structures with an elongated urethra consisting of a morphology that resembled the male urethra were observed (Fig. 3). Ovarian structures were found on the lateral side of the bladder.

Fig. 2.

MRI of the pelvic region. Sagittal sections showing a full bladder filled with contrast and the presence of rudimentary uterine features.

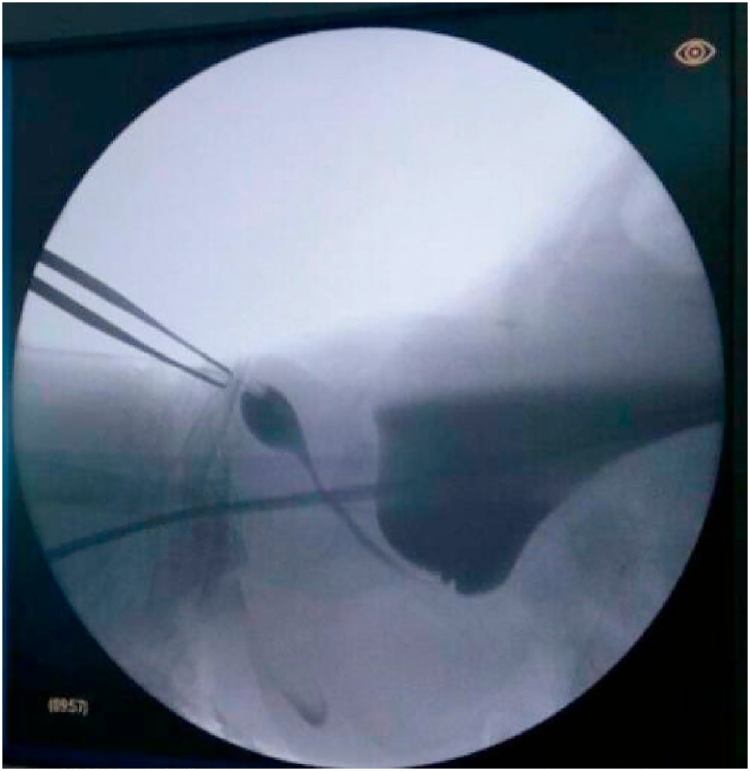

Fig. 3.

Ureterocystography. The long urethral structure resembles a male urethra. In addition, distension of the bladder causing urinary incontinence overflow and vesicoureteral reflux is observed.

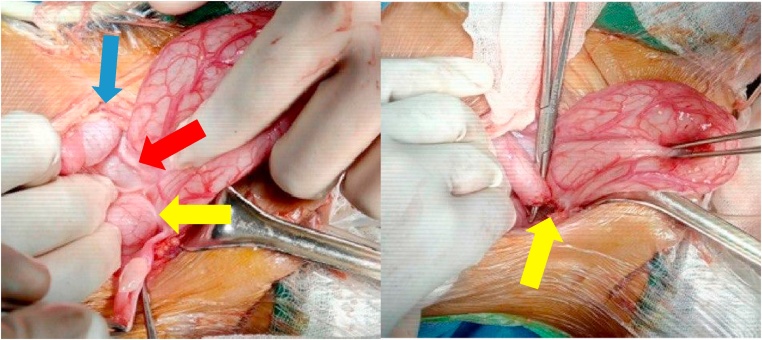

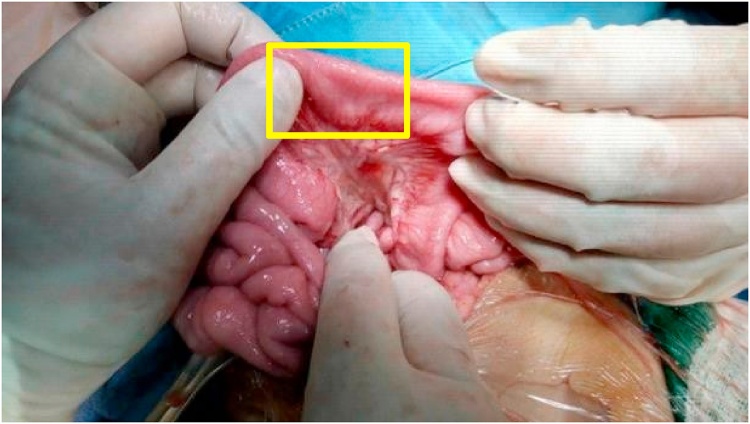

Anal atresia with rectovesical fistula was found intraoperatively. The uterine structure was not visible, and the rudimentary cylindrical vagina was 5 cm in length and 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 4). Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP), vaginal reconstruction using the ileum, and cystostomy were performed. The vagina was reconstructed by cutting the ileum (length, 11 cm) and maintaining the mesoileum 70 cm away from Bauhin's valve (Fig. 5). The ileal segments were sutured proximally between the pelvic muscles, whereas the distal segment was sutured to close the opened lumen. Intraoperative fluoroscopy of the urinary tract was performed by injecting a contrast through the external urethral orifice on the right side of the clitoris.

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative pictures showing the right ovary (yellow arrow), left ovary (blue arrow), and the area where the uterus should have been (red arrow) (image on the left) and the rectovesical fistula (yellow arrow) (image on the right).

Fig. 5.

Segment (yellow area) of the ileum used for vaginal reconstruction.

The intraoperative findings revealed a minimal number of sphincter complex muscles. Stimulation of the anal muscle performed under anesthesia after the wounds of the PSARP and vaginal reconstruction were healed demonstrated the absence of muscle contractions. The lack of anal muscle complexes and presence of complex ARMs resulted in a high probability of experiencing incontinence. The family did not provide permission to perform urethral reconstruction procedures. Right after surgery, we found that reconstructed anal and vagina were vital (Fig. 6). Patient was stable throughout the procedure.

Fig. 6.

Image taken post-PSARP showing the vaginal reconstruction.

The surgery was performed by an attending surgeon and assisted by a surgery resident. The attending surgeon specializes in pediatric surgery with nine years of experience.

Postoperative plan included evaluation of the wound and the stoma. There was no postoperative wound infection, and the stoma was vital and fecal material was present following three days after hospital discharge. In two weeks follow-up, the patient did not have problems with the micturition and there was no presence of fistula. In one month postoperatively, there was no stricture in the artificial vaginal lumen, and fistula was absent. Evaluation plan in two years at hospital setting will be conducted to assess mucous production, presence of fistula or stricture in the artificial structure, dilation of artificial vaginal lumen, and urinary function.

3. Clinical discussion

MRKH syndrome is a collection of several congenital defects classified as Müllerian duct disorders and characterized by the presence of congenital aplasia in the uterus, cervix, and two-thirds of the upper vagina [1,2]. This condition could happen in women who have a normal gene, phenotype, development, and reproductive endocrine functional status (46XX) [2]. The vagina in patients with MRKH syndrome may not be formed at all or may present as a short, clogged structure without a cervix at the apex [1].

MRKH syndrome is rare, and the incidence rate of this condition across the world and in Indonesia is not known with certainty. The study by Eldor et al. [6] reported that the incidence of MRKH syndrome ranged from 1 in 4,000–1 in 80,000 live births. The patients were generally diagnosed past puberty due to the presence of primary amenorrhea or copulation failure; alternatively, cases of MRKH syndrome at an early age were usually detected because of vaginal obstruction, genitourinary anomalies, or suspicion of anomalies on antenatal ultrasound [8].

MRKH syndrome can be classified into two types: types I and II. Type I MRKH syndrome is also called isolated MRKH syndrome/Rokitansky sequence and presents as uterovaginal aplasia alone without any defects in other organs. Type II MRKH syndrome, also called Müllerian duct aplasia, renal aplasia, and cervicothoracic somite dysplasia (MURCS) association, presents with malformations in other organs. Urinary tract abnormalities have been reported in approximately 40% of patients with type II MRKH syndrome. The urinary tract defects include unilateral renal agenesis (23%–28%), ectopia of one or both kidneys (17%), renal hypoplasia (4%), horseshoe kidney, and hydronephrosis [9]. The most common organ defects found in patients with MRKH syndrome include renal (40%–60%), skeletal (10%–12%), hearing (10%), and heart defects [[8], [9], [10]].

MRKH syndrome with ARM is very rare. ARM is a congenital anorectal differentiation disorder that affects the anatomical structure of the anus and rectum. It can manifest as a diverse spectrum with poorer functional prognoses as the malformations become more complex. Levitt and Pena distinguished ARM into two types: syndromic and non-syndromic. Syndromic ARM is associated with genetic disorders; for example, ARM with vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac malformations, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb anomalies syndrome (VACTERL); MURCS, chromosomal trisomy, and various other syndromes. Non-syndromic ARM is further classified into two subgroups: those with and without fistulas [11]. In the current study, the patient belonged to the non-syndromic ARM group with fistulas and presented with anal atresia and a rectovesical/bladder neck fistula. The presence of microcephaly and polydactyly in this patient needs to be investigated further regarding the possibility of other syndromic abnormalities [11].

Wang et al. [8] identified 133 patients with MRKH syndrome at a surgical center in China over a period of 10 years. Three patients (2.25%) had ARMs in the form of an imperforated anus and a rectovestibular fistula. Oppelt et al. [1] reported that among 284 patients with MRKH syndrome, 128 (45.1%) had extragenital malformations and most of them were unilateral renal agenesis (n = 54; 18.8%); however, no cases of ARMs were observed in their study. In a study by Levitt et al. [12], comprising 1007 patients with rectovestibular fistula-type ARMs, the incidence of uterovaginal malformations was 0.6%, and the rate of agenesis among them was 6.6%.

In most of the studies on vaginal and anal reconstruction in patients with MRKH syndrome and ARM, the patients demonstrated a good functioning artificial vagina and anus with adequate discharge. The case series by Kisku et al. [13] presented seven cases of the rectovestibular fistula with vaginal atresia and evaluated the sexual output, urinary function, and fecal continence function of the new vaginal structures, urethra, and anus. Five patients underwent vaginal reconstruction surgery using the post-pubertal sigmoid colon. One patient reported good sexual function with no dyspareunia. The post-vaginal reconstruction complications included mild vaginal prolapse and vaginal stenosis, which required daily digital dilation with anesthesia. The urination and defecation functions of the four patients achieved good continence. One patient had three failed anoplasty and refused to be re-operated. In some cases, the patient may require a laxative. Two infants presented with good urine continence but had an anal mucosal prolapse, which needed to be excised. In addition, these patients present with a higher frequency of defecation, which leads to perianal excoriation [13].

Wester et al. [14] reported seven cases of vaginal agenesis accompanied by various types of ARMs. The vaginal and anal reconstruction techniques used were PSARP with sigmoid vaginoplasty in three cases, anterior sagittal anorectoplasy (ASARP) + colovaginoplasty in one case, and ASARP + vaginal pull-through in three cases. Six patients underwent anorectal and vaginal reconstruction surgery within the first year of life. One other patient underwent vaginal reconstruction at the age of 11 years and a repeat PSARP operation at the same time. Gynecological outcomes were described in two patients. One patient underwent ASARP and vaginal pull-through at 10 months of age and a follow-up at the age of 19. She presented with vaginal introitus stenosis and was undergoing dilation therapy. Her menstrual cycles were normal, and she had no complaints with regards to the defecation process. However, she required intermittent catheterization after undergoing ileocystoplasty due to vesicoureteric reflux. Another patient who underwent ASARP + vaginal pull-through surgery was followed up at the age of 16 years and reported good defecation function with no vaginal stenosis. Four patients who had undergone PSARP surgery + sigmoid colovaginoplasty and followed up at the pre-pubertal age reported the presence of constipation and were treated with laxatives. One other patient operated on at the age of 1 using the ASARP technique with vaginal pull-through reported good defecation function at the age of 9 [14].

The case series from Pandya et al. [15] presented 15 patients with MRKH syndrome with an imperforated anus who generally demonstrated a poor anorectal continence output; in addition, many of the patients had urinary incontinence. The vaginal and anal reconstruction techniques used included abdominoperineal vaginoplasty in four patients, PSARP with vaginoplasty in three patients, laparoscopic-assisted anorectovaginoplasty in four patients, rudimentary uterine/vaginal pull-through in one patient, anoplasty and colovaginoplasty in one patient, and perineal anoplasty in three patients (vaginoplasty was postponed or had not been done). Two out of 12 patients unde rwent vaginal and anal reconstruction surgery at the same time with complications of vaginal stricture in one patient. In patients who had staged procedure, two out of three patients developed vaginal strictures. Furthermore, six patients had good defecation functions, and two had adequate defecation functions [15].

Wang et al. [8] reported three patients with MRKH syndrome accompanied by rectovestibular fistula and an imperforated anus. All three patients were of the post-pubertal age. One patient underwent concurrent vaginal and anal reconstruction surgery, one postponed the surgery, and underwent the other laparoscopic-assisted surgery. The ASARP reconstruction technique was applied to one patient with good postoperative defecation control. Routine dilation therapy is recommended to maintain the vaginal patency. One other patient underwent vaginal reconstruction using Davydov's laparoscopic technique and ASARP followed by a regular postoperative dilation therapy. In the sixth postoperative week, the patient presented with good defecation control, a new vagina (6–7 cm long), and a good perineal appearance. The data regarding these publications are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies elaborating outcomes of anal and vaginal reconstruction.

| Study group | Surgical technique | Age | Parts used | Sexual function | Urinary function | Defecation function | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kisku et al. [13] | Uterosigmoid neovaginoplasty | 18 years | Sigmoid colon | Good | Continence | - | - |

| Uterosigmoid neovaginoplasty | 17 years | - | Not sexually active | - | Refused re-anoplasty, sometimes need a laxative | - | |

| Sigmoid neovaginoplasty | 11 years | Sigmoid | Not sexually active | Continence | - | Light prolapse | |

| Uterosigmoid neovaginoplasty | 17 years | - | Not sexually active | Continence | - | Stenosis requiring daily digital dilatation + dilatation under anesthesia | |

| Uterosigmoid neovaginoplasty + left nephrectomy + ureterocystoplasty | 14 years | - | Not sexually active | Continence | - | Died of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)a and was waiting for a kidney transplant | |

| Laparotomy + ARVFb separation + neoanal creation | 3 months | Rectosigmoid for neoanal creation | Not sexually active | - | Frequent, soiling (+) | Prolapse of the anal mucosa | |

| Laparotomy + ARVF separation + neoanal creation | 1 month | Rectosigmoid for neoanal creation | Not sexually active | - | Frequent, soiling (+) | Prolapse of the anal mucosa | |

| Wester et al. [14] | PSARPc + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | 3 months | Sigmoid | - | - | Constipated | - |

| ASARPd + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | 18 months | Sigmoid | - | - | Constipated | - | |

| PSARP + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | - | - | Normal menstrual cycle | Vesicoureteral reflux | Good | - | |

| Redo PSARP + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | 2.5 years | - | - | - | Constipated | - | |

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 16 years | - | Not sexually active No stenosis | - | - | - | |

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 19 years | - | Vaginal introitus stenosis, not sexually active | - | - | Vaginal introitus stenosis | |

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 9 years | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Abdominoperineal | Average | - | - | 4 patients were okay | 6 patients had good | Colon stricture | |

| ASARP + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | 18 months | Sigmoid | - | - | Constipated | - | |

| PSARP + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | - | - | Normal menstrual cycle | Vesicoureteral reflux | Good | - | |

| Redo PSARP + sigmoid colovaginoplasty | 2.5 years | - | - | - | Constipated | - | |

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 16 years | - | Not sexually active | - | - | - | |

| No stenosis | |||||||

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 19 years | - | Vaginal introitus stenosis, not sexually active | - | - | Vaginal introitus stenosis | |

| ASARP + vaginal pull-through | 9 years | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Pandya et al. [15] | Abdominoperineal with vaginoplasty | Average age range | - | - | - 4 patients were | - 6 patients had functionsdefecation functions | -Colon stricture |

| PSARP with vaginoplasty | 17.6–20.6 months | - | - 3 patients had incontinence | - 2 patients had adequate defecation functions | -Neovaginal stricture | ||

| Laparoscopically assisted anorectovaginopl asty Anoplasty into colovaginoplasty | - | The rest of the patients are too young to be assessed. | Colovaginoplasty stricture | ||||

| - Proximal colon | |||||||

| - Distal part of the rectum | |||||||

| Perineal anoplasty | - | ||||||

| Wang et al. [9] | ASARP | 19 years | - | Good | Good | - | |

| Davydov's laparoscopic technique and ASARP | 27 years | - | Good | Good | - |

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

ARVF: anorectovaginal fistula.

PSARP: posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

ASARP: anterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Some of these case series show that the factor of age at reconstructive surgery affects the successful construction of the artificial vagina and anus. The postoperative success rate of patients who are mature enough is generally good, whereas issues with the artificial anus have been observed in babies. For almost all of the references provided in the current study, vaginal reconstruction was performed immediately after the diagnosis of vaginal agenesis was established. According to the study by Bischoff, the patient has only one chance to undergo reconstructive surgery and a surgical procedure for the other congenital defects [15]. Re-operative procedures do not provide a good functional prognosis. Therefore, in patients with cloaca and other congenital defects involving concurrent anorectal and urogenital malformations, surgical reconstructive procedures for the vagina and artificial anus should be attempted in a single operation to achieve the best functional prognosis [16]. Kubota et al. [17] developed a management algorithm for both type I and type II MRKH syndrome associated with ARM, based on their published algorithms. These guidelines suggest that artificial vaginal and anal reconstruction should be performed in a single operation in patients with type II MRKH syndrome with ARM. In the current study, the vaginal function could not be assessed because of the patient's age and the lack of use for sexual needs.

Several studies have reported the management of cases by gradually separating PSARP with vaginal reconstruction due to the late diagnosis of vaginal agenesis. Almost all patients undergoing post-pubertal vaginal reconstruction after having previously undergone anorectoplasty due to vaginal agenesis were not identified until intraoperative anorectoplasty was performed. In several cases published by Wester et al. [14], there were also cases of MRKH syndrome that were established intraoperatively and immediately under vaginal reconstruction procedures. In the study by Torre et al. [18], all four patients who underwent concurrent anorectoplasty and vaginal reconstruction presented with good defecation function following the administration of laxatives. Likewise, good defecation function following the administration of laxatives was observed in three patients who underwent separate vaginal anorectoplasty and reconstruction. However, the sexual and urinary functions of the patients were not reported.

The postoperative outcome of PSARP and pull-through in patients with complex cases is associated with the risk of fecal incontinence. Levitt and Pena demonstrated that 25% of patients with severe pelvic organ abnormalities were at risk of experiencing post-PARP fecal incontinence or having to undergo other reconstructive procedures [19]. Other studies suggest that 47.5%–53.3% of post-PARP patients will experience fecal incontinence. The most common cause of anal sphincter insufficiency is a minimal defect in the innervation of the sphincter and the muscle complex. Rectal prolapse might be a sign of insufficient post-PSARP sphincter function [[20], [21], [22]]. The existence of a functional internal anal sphincter is very important for a stronger anal tone at the resting state [20]. Another cause for a non-optimal PSARP outcome is the presence of severe sacral bone abnormalities, high rectal malformations (recto-bladder neck fistula and high cloaca), and severe constipation [19,20]. In post-PSARP ARM patients with poor artificial anal function, a permanent colostomy may be used as an alternative for excretion while considering the optimal absorption of the colon [21,22].

Patients with high ARM, hypoplasia of the sphincter muscle, and abnormal innervation of the sacral nerves are at high risk for defecation disorders, both incontinence and constipation. The management of post-PSARP fecal continence disorders is carried out in stages (stepwise) starting from the simplest modality to the addition of other modalities if the previous modality is less effective. The modalities for managing constipation after PSARP include dietary modification, oral laxatives, antegrade continence enema, biofeedback therapy, and surgery. Keeping the patient under regular follow-up is very important to prevent severe constipation that can lead to fecal impaction and megacolon [23].

The operative procedures used to correct post-PARP incontinence include levatorplasty, smooth muscle transposition, sphincteroplasty (with a 25%–83% success rate), gracilis muscle transplant procedure (graciloplasty) or gluteus muscle transplant procedure (gluteoplasty) (with a success rate of 35%–85%, but requires long-term electrical stimulation), and artificial urinary sphincters reconstructon (with a success rate of 20%–60%). Each of these procedures has a 50% chance of developing complications. In such cases, colostomy may be considered after assessing the patient's condition [[24], [25], [26]].

In the study by Tsugawa et al. [24], PSARP re-surgery was performed because of fecal incontinence (n = 16) and fecal impaction (n = 4) in 20 patients with imperforated anus who had previously undergone PSARP pull-through surgery (17 underwent abdomino-sacroperineal or sacroperineal while 3 underwent perineal pull-through surgeries). The PSARP redo technique was chosen for rectal rerouting based on Computed Tomography scan and/or MRI imaging results. The follow-up results over a mean period of 6 years were quite good; two out of four constipated patients reported daily defecation, and 12 out of 16 patients with fecal incontinence reported normal defecation [24]. Ralls et al. [27] performed a laparoscopic salvage anorectoplasty with real-time MRI guidance in a patient who had post-PARP dehiscence for vestibular fistula. The patient developed mild constipation within 1 year postoperatively and was treated with a modified high-fiber diet.

The success rate of the pull-through re-operative procedure varies in terms of the success/rate of improvement of the fecal continence function, which ranges from 25% to 52% [27]. Permanent colostomy may be considered in cases where severe continence disorders persist after various treatment modalities have been attempted [21]. The International Incontinence Society recommends permanent colostomy for the management of fecal incontinence as a grade C recommendation based on two Level 4 studies and consensus opinion. One study showed that the success rate of an end-sigmoid colostomy for treating fecal incontinence of various etiologies could reach 43% for asymptomatic patients. Other studies have explained that colostomy aims to improve the quality of life of patients during adulthood [22,28].

4. Conclusion

In this study, a 15-month-old girl developed MRKH syndrome associated with ARM and a rectovesical fistula. She underwent an ileal segment vaginal reconstruction procedure, PSARP procedure, and pull-through for vaginal reconstruction. The output of the artificial anal function in patients is considered to be associated with a high risk of fecal incontinence. This risk was assessed during the intraoperative and postoperative clinical assessments of the patient. Clinically, the presence of an artificial vaginal discharge from the ileum is vital. However, this function could not be evaluated in the current case due to the age of the patient. Several studies have demonstrated that PSARP and vaginal reconstruction with bowel segments, especially the ileum, provide good functional outcomes. Nonetheless, further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding for research are declared.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Study conception and design: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Baskoro Cahyo Pramudito.

Acquisition of data: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Baskoro Cahyo Pramudito.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Baskoro Cahyo Pramudito.

Drafting of manuscript: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Baskoro Cahyo Pramudito.

Critical revision: Sastiono Soedibyo.

Registration of research studies

Not Applicable.

Guarantor

Tri Hening Rahayatri.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgment

None.

References

- 1.Oppelt P.G., Lermann J., Strick R. Malformations in a cohort of 284 women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH) Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RB&E. 2012;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiaschetti V., Taglieri A., Gisone V. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Role of imaging to identify and evaluate the uncommon variation in development of the female genital tract. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2012;6(4):17–24. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v6i4.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrier D., Mouchel T., Pasquier L. The Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (congenital absence of uterus and vagina)—phenotypic manifestations and genetic approaches. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2006;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajimwale A., Furness P.D., 3rd, Brant W.O. Vaginal construction using sigmoid colon in children and young adults. BJU Int. 2004;94(1):115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-4096.2004.04911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao L.-M., Conway G.S., Ismail-Pratt I. Emotional and sexual wellness and quality of life in women with Rokitansky syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205(2):117.e111–117.e116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eldor L., Friedman J.D. Reconstruction of congenital defects of the vagina. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2011;25(2):142–147. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R., Franchi T., Sohrabi C. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S., Lang J.H., Zhu L. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küester-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome with rectovestibular fistula and imperforate anus. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010;153(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morcel K., Camborieux L., Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007;2(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edmonds D.K. Congenital malformations of the genital tract and their management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003;17(1):19–40. doi: 10.1053/ybeog.2003.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levitt M.A., Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitt M.A., Bischoff A., Breech L. Rectovestibular fistula rarely recognized associated gynecologic anomalies. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009;44(6):1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kisku S., Barla R.K., Sen S. Rectovestibular fistula with vaginal atresia: our experience and a proposed course of management. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2014;30(6):633–639. doi: 10.1007/s00383-014-3517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wester T., Tovar J.A., Rintala R.J. Vaginal agenesis or distal vaginal atresia associated with anorectal malformations. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2012;47(3):571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandya K.A., Koga H., Okawada M. Vaginal anomalies and atresia associated with imperforate anus: diagnosis and surgical management. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015;50(3):431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bischoff A. The surgical treatment of cloaca. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2016;25(2):102–107. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota M., Osuga Y., Kato K. Treatment guidelines for persistent cloaca, cloacal exstrophy, and Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Häuser syndrome for the appropriate transitional care of patients. Surg. Today. 2019;49(12):985–1002. doi: 10.1007/s00595-019-01810-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De la Torre L., Cogley K., Calisto J.L. Vaginal agenesis and rectovestibular fistula. Experience utilizing distal ileum for the vaginal replacement in these patients, preserving the natural fecal reservoir. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016;51(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levitt M.A., Peña A. Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2005;17(3):394–401. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000163665.36798.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rintala R.J., Lindahl H. Secondary posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for anorectal malformations. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 1995;10(5):414–417. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasgow R.E. Complications in surgery. Ann. Surg. 2006;244(5):837. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Divarci E., Ergun O. General complications after surgery for anorectal malformations. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2020;36(4):431–445. doi: 10.1007/s00383-020-04629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyrklund K., Pakarinen M.P., Rintala R.J. Long-term bowel function, quality of life and sexual function in patients with anorectal malformations treated during the PSARP era. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2017;26(5):336–342. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsugawa C., Hisano K., Nishijima E. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for failed imperforate anus surgery: lessons learned from secondary repairs. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000;35(11):1626–1629. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.18337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holschneider A.M. Complications following posterior sagittal approach-PSARP. 日本小児外科学会雑誌. 2003;39(7):903–908. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bischoff A., Levitt M.A., Peña A. Bowel management for the treatment of pediatric fecal incontinence. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2009;25(12):1027–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2502-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ralls M.W., Fallon B.P., Ladino-Torres M. Salvage laparoscopic-assisted anorectoplasty after failed vestibular fistula repair using magnetic resonance image guidance. European J. Pediatr. Surg. Rep. 2019;7(1):e12–e15. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Consultation on I, Abrams P., Cardozo L. ICUD-EAU; Paris: February 2012. Incontinence: 5th International Consultation on Incontinence, Paris. [Google Scholar]