Key Points

Question

What are the insurance acceptance practices, wait times, and clinician availability at dermatology clinics with and without private equity (PE) ownership?

Findings

In this cross-sectional, secret-shopper study of 611 dermatology clinics, patients with Medicaid had significantly longer wait times and lower success in obtaining an appointment compared with patients with private insurance or Medicare, regardless of clinic ownership. Private equity–owned clinics had increased appointment availability with nonphysician clinicians and decreased appointment availability with dermatologists.

Meaning

Dermatology access for patients with Medicaid remains limited across PE and non-PE clinics and should be monitored as the dermatology practice landscape continues to evolve.

Abstract

Importance

In the 15 years since dermatology access was last investigated on a national scale, the practice landscape has changed with the rise of private equity (PE) investment and increased use of nonphysician clinicians (NPCs).

Objective

To determine appointment success and wait times for patients with various insurance types at clinics with and without PE ownership.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this study, PE-owned US clinics were randomly selected and matched with 2 geographically proximate clinics without PE ownership. Researchers called each clinic 3 times over a 5-day period to assess appointment/clinician availability for a fictitious patient with a new and changing mole. The 3 calls differed by insurance type specified, which were Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) preferred provider organization, Medicare, or Medicaid.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Appointment success and wait times among insurance types and between PE-owned clinics and control clinics. Secondary outcomes were the provision of accurate referrals to other clinics when appointments were denied and clinician and next-day appointment availability.

Results

A total of 1833 calls were made to 204 PE-owned and 407 control clinics without PE ownership across 28 states. Overall appointment success rates for BCBS, Medicare, and Medicaid were 96%, 94%, and 17%, respectively. Acceptance of BCBS (98.5%; 95% CI, 96%-99%; P = .03) and Medicare (97.5%; 95% CI, 94%-99%; P = .02) were slightly higher at PE-owned clinics (compared with 94.6% [95% CI, 92%-96%] and 92.8% [95% CI, 90%-95%], respectively, at control clinics). Wait times (median days, interquartile range [IQR]) were similar for patients with BCBS (7 days; IQR, 2-22 days) and Medicare (7 days; IQR, 2-25 days; P > .99), whereas Medicaid patients waited significantly longer (13 days; IQR, 4-33 days; P = .002). Clinic ownership did not significantly affect wait times. Private equity–owned clinics were more likely than controls to offer a new patient appointment with an NPC (80% vs 63%; P = .001) and to not have an opening with a dermatologist (16% vs 6%; P < .001). Next-day appointment availability was greater at PE-owned clinics than controls (30% vs 21%; P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with Medicaid had significantly lower success in obtaining appointments and significantly longer wait times regardless of clinic ownership. Although the use of dermatologists and NPCs was similar regardless of clinic ownership, PE-owned clinics were more likely than controls to offer new patient appointments with NPCs.

This cross-sectional study examines appointment success and wait times for patients with various insurance types at clinics with and without private equity ownership.

Introduction

Access to dermatology appointments is affected by factors, including geography, chief complaint, clinician type, and insurance/payment type.1,2,3,4,5,6 Patients with Medicaid face substantially lower acceptance rates and longer wait times compared with patients with private insurance.4,5 Dermatology access for medical appointments has not been assessed on a national scale in 15 years.1 Within this period, the practice landscape has seen a rise in private equity (PE) investment and the use of nonphysician clinicians (NPCs).7,8,9,10,11,12 Private equity investment in dermatology practices and the use of NPCs have recently been found to be associated,13 yet, to our knowledge, whether either of these affects access to care has yet to be studied on a national scale.7,9,14,15

Private equity firms invest in dermatology practices and aim to enhance their financial performance,16,17,18,19 causing physicians to express concern that the fiduciary responsibility of PE firms may incentivize operational changes at dermatology practices that jeopardize access to or reduce the quality of care for patients.14,15,20 This can include increasing use of NPCs,13 whose reduced salaries and increased performance of billable procedures would benefit the financial goals of these firms.11,20,21,22,23,24 In this study, we sought to (1) provide an updated analysis of dermatology appointment access and wait times for patients with different insurance types, and (2) compare dermatology appointment access and clinician availability between clinics with and without PE ownership.

Methods

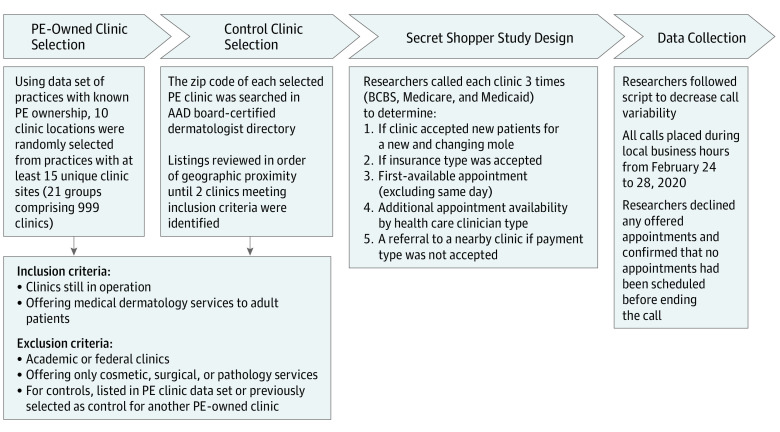

We randomly selected dermatology clinics with PE ownership that were identified in a previous cohort study.8 We matched each of these PE-owned clinics with the 2 nearest clinics that did not have PE ownership. Researchers called each clinic 3 times over a 5-day period to assess insurance acceptance and appointment availability for a fictitious patient with a new and changing mole. The 3 calls differed by insurance type specified: Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) preferred provider organization (PPO), Medicare, or Medicaid (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Clinic Selection and Study Design.

Summary of the criteria for clinic selection and study design. AAD indicates American Academy of Dermatology; BCBS, Blue Cross Blue Shield; PE, private equity.

Selection of PE-Owned Clinics

Five financial databases were systematically searched to identify dermatology management groups (DMGs) (ie, physician practice management companies that operate dermatology clinics) and other dermatology practices that had received PE investment using a previously described methods.8 Thirty-nine DMGs and practices were identified, 35 (89.7%) of which had active PE investors and were still operating in July 2019. The official websites of the 35 entities were then searched online during an assessment period from July 1 to July 5, 2019, to determine the clinic locations owned by each. In total, 1076 clinic locations were identified, 1001 (93%) of which were owned by the largest 21 entities (which each operated 19 to 154 clinics, or 999 in aggregate).

We used a random number generator to assign random numbers to each clinic location within practice groups with at least 15 locations (21 groups comprising 999 clinics) and then screened the locations in numerical order until 10 locations that met inclusion criteria were selected. Clinic locations still operating as of February 21, 2020, that provided adult medical dermatology services were included. Academic and federal clinics, as well as clinics that provided only cosmetic, surgical, or pathology services, were excluded. In total, these criteria resulted in the selection of 210 PE-owned clinics, representing 19.5% of all clinics with known PE ownership as of July 3, 2019 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Non PE-Owned (Control) Clinic Selection

Two unique and geographically matched clinics that were not PE-owned (referred to as control clinics hereafter for simplicity) were selected as controls for each included PE-owned clinic. Control clinics were selected by searching the zip code of each PE-owned clinic in the American Academy of Dermatology physician directory and identifying dermatologists who were working at other nearby clinics.1,2 Results were reviewed sequentially in order of geographic distance until 2 clinics without PE ownership were identified that met the same inclusion criteria that were used for the PE-owned clinics.

Study Design

We used a secret-shopper study design,25 in which researchers call clinics as, or on behalf of, fictitious patients who are inquiring about appointment availability.1,2,26,27,28,29 Researchers (A.C., S.D., S.J.L., K.L., K.L., A.N.B., and C.V.) were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 study arms: BCBS PPO, Medicare, or Medicaid. One researcher from each arm called every included dermatology clinic and inquired on behalf of a family member about appointment availability for a new patient with a new and changing mole.

Researchers followed a prepared script to reduce intra- and inter-researcher call variability (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) and sequentially (1) confirmed that the clinic was accepting new patients for the stated chief complaint, (2) confirmed whether their assigned insurance type was accepted and asked for a referral to another clinic if it was not, (3) inquired about the first available appointment and the credentials of the assigned clinician, and (4) inquired about additional appointment availability with clinicians who had different credentials. Before completing each call, the researcher stated that they would need to check their family member’s availability before confirming the appointment and verified that no appointment had been scheduled.

Data Collection

Researchers on each study arm placed calls to all selected clinics within 5 calendar days (February 24-28, 2020) during local business hours (8:30 am-4:30 pm). If a clinic was successfully contacted for that particular study arm, the clinic was marked as complete in that arm’s call log and the associated call data were recorded. Alternatively, researchers documented instances when a clinic did not answer the phone or placed the caller on hold for longer than 6 minutes. If either of these scenarios occurred on 3 different days for the same study arm, the encounter was categorized as an appointment failure. Some clinics that did not accept a given insurance were able to refer the caller to another clinic. In those cases, we confirmed insurance acceptance at the referred clinic with calls on March 3, 2020.

For all clinics, the practice website was searched to collect data on the number of employed dermatologists and NPCs, defined as physician assistant (PA) or nurse practitioner (NP) clinicians, as well as additional clinic locations part of the same practice. At the time of this study, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic had not affected clinic schedules or availability in the US. This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham institutional review board.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcomes were appointment success and appointment wait times between study arms (Medicare vs BCBS PPO and Medicaid vs BCBS PPO) and between PE-owned and control clinics. Appointment success was defined as a scenario in which the clinic accepted the insurance type and the researcher could therefore inquire about appointment availability with any clinician at any time in the future. Appointment failure was defined as a scenario in which the clinic did not accept the insurance type, or the researcher was unable to contact the clinic according to our previously stated criteria. Appointment wait times were calculated in calendar days, with day 1 defined as the first day after the completed phone call.

Secondary outcomes were the provision of accurate referrals to other clinics when appointments were denied, and clinician and next-day appointment availability. Referral success was defined as a scenario in which clinics that did not accept the stated insurance type offered a referral to another clinic that, when contacted by our study team to confirm, did in fact accept the stated insurance type.

Statistical Analysis

The overall omnibus comparisons between the 3 types of insurance were conducted by Pearson χ2 tests for appointment success and Kruskal-Wallis test for appointment wait times. Following significant omnibus test results, the pairwise comparisons between insurance types were conducted using Fisher exact tests for appointment success and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for appointment wait times. A Bonferroni-corrected P value threshold of .05/3 = 0.017 was used for statistical significance of pair-wise comparison between insurance types.

The comparison between PE-owned and control clinics was conducted using a conditional logistic regression that accounted for the pairing of PE-owned clinics with their 2 geographically matched controls.30 Because the PE-owned clinics were not selected using the American Academy of Dermatology physician directory, we excluded all PE-owned clinics with no physician clinicians listed on their website (n = 11) from the comparative analyses of clinician availability. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.0; R Foundation).

Results

This analysis included 611 clinics that spanned 28 states, necessitating 1833 total calls across all 3 study arms. Data from 16 calls (2.6%) to PE-owned clinics and 53 calls (4.3%) to control clinics were excluded (Table 131; eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Clinic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PE-owned clinics (n = 204) | Controls (n = 407) | |

| No. of clinicians, median (IQR)a | ||

| MD/DO | 2 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) |

| PA/NP | 1 (1-2) | 1 (0-2) |

| No. of additional locations within the same practice, median (IQR)a | 39 (29-49) | 0 (0-1) |

| Miles between PE-owned and control clinics, median (IQR)b | 3.8 (1.4-8.9) | |

| Total No. of calls to be placed, No. of calls | 612 | 1221 |

| Clinic/insurance type combinations marked as appointment failure after 3 unsuccessful contact attempts | 6 (1.0) | 22 (1.8) |

| Excluded from analysis | 16 (2.6) | 52 (4.3) |

| Not accepting new patients | 9 (1.5) | 33 (2.7) |

| Same-day appointment mistakenly accepted by researcher (protocol was to not accept same-day appointments) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (0.7) |

| Clinic was marked as contacted in the call log but associated call data were missing | 5 (0.8) | 11 (0.9) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; PE, private equity.

Based on information provided on clinic websites.

Clinic addresses were geocoded using Geocodio (Dotsquare LLC), and Euclidean distances between PE-owned and control clinics were calculated with a developed formula.31

Clinic Characteristics

According to practice websites, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of total clinicians employed by included PE-owned and control clinics, respectively, were 2 (IQR, 1-3) and 1 (IQR, 1-3) for dermatologists (MD and DO), and 1 (IQR, 1-2) and 1 (IQR, 0-2) for NPCs (Table 1). The median distance between PE-owned clinics and their controls was 3.8 miles (IQR, 1.4-8.9 miles).

Appointment Success

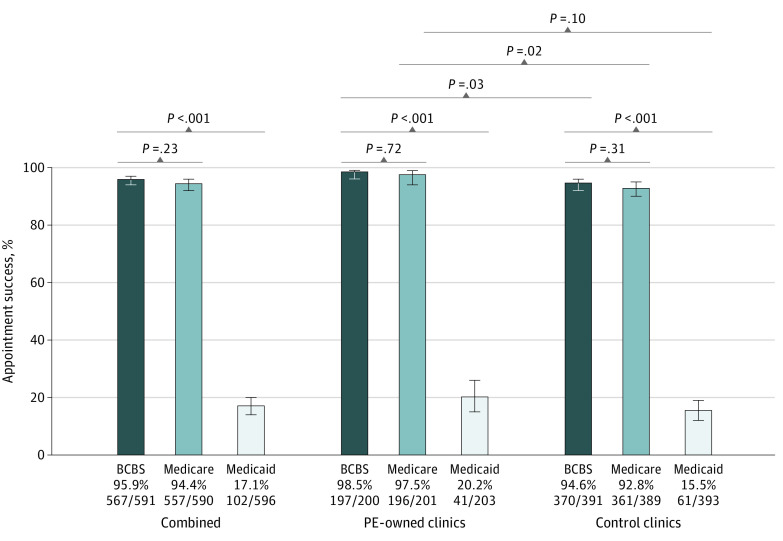

Appointment success was more than 92% for patients with BCBS and Medicare at PE-owned clinics (BCBS, 98.5%; 95% CI, 96%-99%; Medicare, 97.5%; 95% CI, 94%-99%; P = .72) and control clinics (BCBS, 94.6%; 95% CI, 92%-96%; Medicare, 92.8%; 95% CI, 90%-95%; P = .31; Figure 2). Compared with patients with BCBS, the appointment success for patients with Medicaid was significantly lower at PE-owned clinics (20.2%; 95% CI, 15%-26%; P < .001) and control clinics (15.5%; 95% CI, 12%-19%; P < .001). Greater appointment success at PE-owned clinics compared with controls reached statistical significance for BCBS and Medicare, but not for Medicaid.

Figure 2. Appointment Success by Clinic and Insurance Type.

Representation of the percentage of clinics (either private equity [PE]–owned, control clinic, or combined) that accepted the 3 different insurance types. For pairwise comparisons between the 3 payment types, the Bonferroni‐corrected P value threshold for statistical significance is 0.05/3=0.017. BCBS indicates Blue Cross Blue Shield.

Appointment Wait Times for New Patients for Any Clinician and Dermatologist Only

For all clinics combined, patients with Medicaid had significantly longer appointment wait times (median, 13 days; IQR, 4-33 days; P = .002) compared with patients with BCBS (7 days; IQR, 2-22 days), whereas Medicare patients had similar wait times as BCBS patients (7 days; IQR, 2-25 days; Table 2; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The observed difference between wait times for Medicaid patients at PE-owned clinics (20 days; IQR, 2-38 days) and control clinics (11 days; IQR, 5-30 days; P = .51) did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2. Appointment Wait Times.

| Characteristic | BCBS | P value | Medicare | P valuea | Medicaid | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First available appointment for any clinician, median calendar days (IQR)b | ||||||

| Comparison with BCBS | ||||||

| All clinics | 7 (2-22) | NA | 7 (2-25) | >.99 | 13 (4-33) | .002 |

| PE-owned clinics | 6 (1-26) | 5 (1-24) | .98 | 20 (2-38) | .02 | |

| Control clinics | 7 (2-21) | 7 (2-25) | .96 | 11 (5-30) | .06 | |

| Comparison between PE-owned and control clinics | ||||||

| PE-owned clinics | 6 (1-26) | .67 | 5 (1-24) | .42 | 20 (2-38) | .51 |

| Control clinics | 7 (2-21) | 7 (2-25) | 11 (5-30) | |||

| First available appointment for MD/DO clinician, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Comparison with BCBS | ||||||

| All clinics | 13 (4-34) | NA | 13 (4-33) | .95 | 22 (7-43) | .007 |

| PE-owned clinics | 10 (4-30) | 10 (3-33) | .92 | 22 (7-43) | .049 | |

| Control clinics | 14 (5-34) | 14 (5-34) | .98 | 22 (8-42) | .06 | |

| Comparison between PE-owned and control clinics | ||||||

| PE-owned clinics | 10 (4-30) | .53 | 10 (3-33) | .57 | 22 (7-43) | .64 |

| Control clinics | 14 (5-34) | 14 (5-34) | 22 (8-42) | |||

Abbreviations: BCBS, Blue Cross Blue Shield; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; PE, private equity.

For pairwise comparisons between the 3 payment types, the Bonferroni-corrected P value threshold for statistical significance is 0.05/3 = 0.017.

Day 1 was the next day after the call was placed.

For appointments specifically with a dermatologist (MD or DO) across all clinics combined, wait times for patients with Medicaid (median, 22 days; IQR, 7-43 days) were significantly longer than wait times for patients with BCBS (13 days; IQR, 4-34 days; P = .01). Wait times for patients with Medicare were statistically similar to those for patients with BCBS (13 days; IQR, 4-33 days). Wait times for all insurance types between PE-owned clinics and control clinics were similar.

Clinic Referrals for Callers Rejected Because of Insurance Type

Of the clinics that did not accept the stated insurance type, patients were offered a referral to another clinic on the caller’s request in 2 of 10 BCBS cases (20%), 0 of 16 Medicare cases (0%), and 60 of 488 Medicaid cases (12.3%) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). On calling the clinics to which the researcher was referred, the percentage of clinics that actually accepted the stated insurance type was 1 of 2 (50%) for BCBS and 35 of 60 (58.3%) for Medicaid. Therefore, of the clinics that rejected callers because of insurance type, the proportion that provided correct referrals was 1 of 10 (10.0%) for BCBS and 35 of 488 (7.2%) for Medicaid, with no statistically significant difference between PE-owned and control clinics.

Clinician and Next-Day Appointment Availability

An NPC was the clinician for the first appointment offered on 51% (95% CI, 46%-56%) of calls with PE-owned clinics compared with 39% (95% CI, 36%-43%; P = .01) of calls with control clinics (Table 3). Private equity–owned clinics were more likely than their corresponding controls to have appointments available with NPCs (80%; 95% CI, 75%-84%; vs 63%; 95% CI, 59%-67%; P = .001) and to not have a dermatologist available to see new patients for evaluation of a new and changing mole (16%; 95% CI, 12%-20%; vs 6%; 95% CI, 5%-8%; P < .001). Next-day appointment availability with any clinician was greater at PE-owned than control clinics (30%; 95% CI, 26%-35%; vs 21%; 95% CI, 19%-24%; P = .001) although not statistically significant for next-day appointments with dermatologists specifically (15%; 95% CI, 12%-19%; vs 13%; 95% CI, 11%-15%; P = .16).

Table 3. Clinician and Next-Day Appointment Availability.

| Appointment | No./Total No. (%) [95% CI] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calls to PE-owned clinics | Calls to control clinics | ||

| First appointment offered with an NPCa | 201/395 (51) [46-56] | 301/765 (39) [36-43] | .01 |

| Next-day appointmentb | |||

| Any clinician type | 127/419 (30) [26-35] | 163/765 (21) [19-24] | .001 |

| MD/DO onlya | 61/395 (15) [12-19] | 97/765 (13) [11-15] | .16 |

| Appointments | |||

| Available with NPCsa,c | 267/335 (80) [75-84] | 421/668 (63) [59-67] | .001 |

| Not available with MD/DOa | 62/395 (16) [12-20] | 48/765 (6) [5-8] | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NPC, nonphysician clinicians; PE, private equity.

Denominator excludes 24 calls to 11 PE clinics without dermatologist availability according to their website.

For calls placed on Friday, February 28, 2020 (1.6% of all placed calls), Monday, March 2, 2020, was used to calculate next-day appointment availability.

To maintain consistency in our call script, we were not able to inquire about NPC availability on calls that offered a next-day appointment with a dermatologist. These calls (n = 61 and n = 97 for PE-owned and control, respectively) were thus excluded from the analysis of appointments available with NPCs.

Discussion

In this study, we found that across all clinics, most patients with private insurance (BCBS) and Medicare were successful in finding appointments, with a 96% and 94% appointment success, respectively. Appointment success for patients with private insurance and Medicare were slightly higher at PE-owned vs control clinics. Dermatology appointment wait times for new patients at PE-owned (median, 6 days; IQR, 1-27 days) and control clinics (median, 7 days; IQR, 2-23 days; eFigure 2 in the Supplement) were not significantly different and were shorter than previously reported (median, 26-29 days; IQR, 14-54 days).1,4

In contrast, similar to previous studies, clinics consistently failed to serve patients with Medicaid (17.1% appointment success).4,5 Additionally, as in prior studies, patients with Medicaid who were able to find appointments had significantly longer wait times than those with private insurance.4 Only 7.2% of the clinics in our analysis that did not accept Medicaid were able to correctly refer patients to another clinic that did accept this insurance, potentially leaving many patients without access to care.

While appointment success, wait times, and referrals were not statistically significantly different for patients with Medicaid at clinics with and without PE ownership, access to care for patients with Medicaid was uniformly poor. These findings are concerning, especially given our caller’s chief complaint of a new and changing mole, as previous studies have found Medicaid and low socioeconomic status to be associated with worse outcomes for patients with melanoma.32,33,34

Although these results do not allow us to determine the motivations behind the decisions of clinics to either not accept patients with Medicaid or accept but offer appointments with longer wait times, existing data suggest that acceptance of Medicaid is likely directly associated with low reimbursement rates.4,35 This hypothesis is further supported by studies outside of dermatology that show that efforts to improve Medicaid access, without concurrent changes to clinician reimbursements, had a null or detrimental association with appointment access compared with states that did not increase access to Medicaid.26,27,28 The explanation for the longer wait times faced by patients with Medicaid is unknown, but may be attributed to efforts by clinics to limit the number of patients with lower-reimbursing insurance.4

Private equity–owned clinics offered slightly greater appointment success for new patients with private insurance or Medicare, as well as slightly greater availability of next-day appointments, possibly because of greater availability of and/or preferential scheduling with NPCs. Despite similar employment ratios, PE-owned clinics were more likely to have available appointments with NPCs and less likely to have any available appointments with dermatologists. In this way, PE-owned clinics improved access to dermatology care with NPCs, but reduced access to dermatologists.

Dermatology practice ownership by PE firms has been demonstrated to be associated with increased hiring of NPCs,13 and hypothesized to lead to an increased likelihood that these clinicians do not receive adequate supervision from the physicians who oversee them.9,14,15,20,36 While use of NPCs has broadly increased over time in dermatology clinics of varied practice type and geography,1,6,10,12 our results based on directly inquiring about clinician availability demonstrated that PE-owned clinics were more likely to offer appointments with NPCs than their geographically matched controls, a finding consistent with a recent study analyzing clinician use at PE-owned clinics.13

Although PE-owned clinics were less likely than controls to offer new patient appointments with dermatologists at any point in the future, employment of dermatologists and NPCs was similar at PE-owned clinics and control clinics, according to practice websites (Table 1). Dermatologists may be occupying an oversight position either in person or remotely, or dermatologists may have filled patient panels, preventing them from accepting appointments with new patients, hypotheses that our methods do not allow us to evaluate.

Furthermore, despite slightly better appointment access at PE-owned clinics, outside of next-day appointments, patients with private insurance and Medicare still faced similar wait times at PE-owned and control clinics, suggesting that the increased availability of NPCs does not affect average appointment wait time, which is consistent with previous findings.6 The increased use of NPCs also did not have an association with access or wait time for Medicaid patients.

Previous studies have found that NPCs exhibited decreased accuracy in diagnosing skin cancer compared with dermatologists, which led to an increase in unnecessary procedures.11,20,21,22,23,24 Therefore, it remains unknown whether and in which clinical scenarios increased access to care with NPCs outweighs tradeoffs in clinical management. Patient outcomes under the care of NPCs will need to be studied on a larger scale to better determine the overall association with patient care and health care expenditures. These types of studies remain difficult to perform, especially because diagnostic accuracy and treatment success are not typically captured in claims data.

Limitations

Although our selection process resulted in the inclusion of 611 clinics from 28 states, our study was designed to primarily analyze appointment access at a sample of clinics with and without PE ownership and may not be representative of the entire national dermatology clinic landscape.1,2 The financial databases we used depend on selectively, self-reported deal information from PE firm general partners. Therefore, the strength of our data set depends entirely on volunteered information.

Our data set of clinics with known PE ownership was updated as of July 3, 2019, and it is possible that some of our control clinics could have been acquired by PE firms subsequent to this date and before our phone calls. It is also possible, because some of the acquisitions by PE firms were relatively recent, that the ultimate effects of PE investment in dermatology practices are not yet reflected in these data. Clinic characteristics were based on practice websites that are updated with unknown frequency. Appointment wait times are dynamic, and our results may not reflect seasonal trends in wait times. While appointment availability can hypothetically change within a matter of days, our study completion time of 5 calendar days is the shortest time frame of any secret-shopper study we could find in the literature, with previous studies ranging from 15 days to 7 months.1,2,26,27,28,29 This study assessed new patient appointments; wait times and clinician availability may be different for follow-up appointments.

Conclusions

We found that appointment success rates for patients with private insurance and Medicare were high, yet slightly higher at PE-owned vs control clinics. Patients with Medicaid, regardless of dermatology clinic ownership, had significantly lower success in obtaining an appointment for a new and changing mole. Although wait times for all insurance types were improved compared with previously published data, the continued insufficient access and longer waits for patients with Medicaid demands attention. Furthermore, we found differences in clinician availability for new patients between PE-owned clinics and their geographically matched controls, with PE-owned clinics exhibiting increased appointment availability with NPCs and decreased appointment availability with dermatologists. It will be important to monitor how dermatology access, especially for patients with Medicaid, changes as payment and care delivery models evolve.

eFigure 1. Caller script

eFigure 2. Boxplot of median wait time for first available appointment with any provider

eTable 1. Clinic locations by state

eTable 2. Referral success

References

- 1.Tsang MW, Resneck JS Jr. Even patients with changing moles face long dermatology appointment wait-times: a study of simulated patient calls to dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(1):54-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resneck JS Jr, Lipton S, Pletcher MJ. Short wait times for patients seeking cosmetic botulinum toxin appointments with dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):985-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman SR, Resneck JS Jr. Commentary: the relative ease of obtaining a dermatologic appointment in Boston: how methods drive results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(6):949-950. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resneck J Jr, Pletcher MJ, Lozano N. Medicare, Medicaid, and access to dermatologists: the effect of patient insurance on appointment access and wait times. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):85-92. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02463-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resneck JS Jr, Isenstein A, Kimball AB. Few Medicaid and uninsured patients are accessing dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(6):1084-1088. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zurfley F Jr, Mostow EN. Association between the use of a physician extender and dermatology appointment wait times in Ohio. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(12):1323-1324. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, Mostaghimi A. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seiger K, Tkachenko E, Mostaghimi A. Growth of private equity in dermatology through acquisitions and new clinic formation, 2018-2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)32634-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konda S, Francis J, Motaparthi K, Grant-Kels JM; Group for Research of Corporatization and Private Equity in Dermatology . Future considerations for clinical dermatology in the setting of 21st century American policy reform: corporatization and the rise of private equity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):287-296.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):746-752. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers AT, Bai G, Loss MJ, Anderson GF. Increasing frequency and share of dermatologic procedures billed by nonphysician clinicians from 2012 to 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(6):1159-1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2):211-216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skaljic M, Lipoff JB. Association of private equity ownership with increased employment of advanced practice professionals in outpatient dermatology offices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30855-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resneck JS Jr Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):13-14. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharfstein JM, Slocum J. Private equity and dermatology—first, do no harm. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacArthur HH Bain & Co: global private equity report 2018. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.bain.com/insights/global-private-equity-report-2018/

- 17.McKinsey and Co The rise and rise of private markets. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/private equity and principal investors/our insights/the rise and rise of private equity/the-rise-and-rise-of-private-markets-mckinsey-global-private-markets-review-2018.ashx.

- 18.MacArthur H, Elton G, Haas D, Varma S Rewriting the private equity playbook to combine cost and growth. Accessed February 25, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/baininsights/2017/04/08/rewriting-the-private-equity-playbook-to-combine-cost-and-growth/#23fe636a4445

- 19.Greenfield M Private equity firms increase focus on add-ons. Accessed February 25, 2019. https://www.pehub.com/private-equity-firms-increase-focus-on-add-ons/

- 20.Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(9):1040-1044. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Q, Hibler BP, Coldiron B, Rossi AM. Analysis of dermatologic procedures billed independently by non-physician practitioners in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;S0190-9622(18)32574-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nault A, Zhang C, Kim K, Saha S, Bennett DD, Xu YG. Biopsy use in skin cancer diagnosis: comparing dermatology physicians and advanced practice professionals. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(8):899-902. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, Secrest AM, Ferris LK. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):569-573. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Privalle A, Havighurst T, Kim K, Bennett DD, Xu YG. Number of skin biopsies needed per malignancy: comparing the use of skin biopsies among dermatologists and nondermatologist clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):110-116. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blinkhorn L Secret shoppers and conflicts of interest. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(2):119-124. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.2.bndr1-1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiznia DH, Maisano J, Kim CY, Zaki T, Lee HB, Leslie MP. The effect of insurance type on trauma patient access to psychiatric care under the Affordable Care Act. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;45:19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiznia DH, Nwachuku E, Roth A, et al. The influence of medical insurance on patient access to orthopaedic surgery sports medicine appointments under the affordable care act. Orthop J Sport Med. Published online July 7, 2017. doi: 10.1177/2325967117714140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiznia DH, Ndon S, Kim C-Y, Zaki T, Leslie MP. The effect of insurance type on fragility fracture patient access to endocrinology under the Affordable Care Act. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2017;8(1):23-29. doi: 10.1177/2151458516681635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YH, Chen AX, Varadaraj V, et al. Comparison of access to eye care appointments between patients with Medicaid and those with private health care insurance. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(6):622-629. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly MA, Liang KY. Conditional logistic regression models for correlated binary data. Biometrika. 1988. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.3.501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veness C Vincenty solutions of geodesics on the ellipsoid. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.movable-type.co.uk/scripts/latlong-vincenty.html

- 32.Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18 to 64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):309-316. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamson AS, Zhou L, Baggett CD, Thomas NE, Meyer AM. Association of delays in surgery for melanoma with insurance type. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(11):1106-1113. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zell JA, Cinar P, Mobasher M, Ziogas A, Meyskens FL Jr, Anton-Culver H. Survival for patients with invasive cutaneous melanoma among ethnic groups: the effects of socioeconomic status and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(1):66-75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perloff JD, Kletke P, Fossett JW. Which physicians limit their Medicaid participation, and why. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1):7-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hafner K, Palmer G Skin cancers rise, along with questionable treatments. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/20/health/dermatology-skin-cancer.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Caller script

eFigure 2. Boxplot of median wait time for first available appointment with any provider

eTable 1. Clinic locations by state

eTable 2. Referral success