Abstract

Background:

Half of women use alcohol in the first weeks of gestation, but most stop once pregnancy is detected. The relationship between timing of alcohol use cessation in early pregnancy and spontaneous abortion risk has not been determined.

Objective:

Evaluate the association between week-by-week alcohol consumption in early pregnancy and spontaneous abortion.

Study Design:

Participants in Right from the Start, a community-based prospective pregnancy cohort, were recruited from eight metropolitan areas in the United States (2000–2012). In the first trimester, participants provided information about alcohol consumed in the prior four months including whether they altered alcohol use, date of change in use, and frequency, amount, and type of alcohol consumed before and after change. We assessed the association between spontaneous abortion and week of alcohol use, cumulative weeks exposed, number of drinks per week, beverage type, and binge drinking.

Results:

Among 5,353 participants, 49.7% reported using alcohol during early pregnancy and 12.0% miscarried. Median gestational age at change in alcohol use was 29 days (inter-quartile range, 15–35 days). Alcohol use during weeks five through ten from last menstrual period was associated with increased spontaneous abortion risk, with risk peaking for use in week nine. Each successive week of alcohol use was associated with an 8% increase in spontaneous abortion relative to those who did not drink (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.04–1.12). This risk is cumulative. Risk was not related to number of drinks per week, beverage type, or binge drinking.

Conclusion:

Each additional week of alcohol exposure during the first trimester increases risk of spontaneous abortion, even at low levels of consumption and when excluding binge drinking.

Keywords: Alcohol, miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, spontaneous abortion, pregnancy, prospective cohort

INTRODUCTION

The line between how alcohol is used “before” and “during” pregnancy is blurred in the first weeks of gestation. While 10% of women continue to use alcohol through pregnancy, as many as half of pregnancies are exposed around conception.1–5 The tendency to use alcohol until pregnancy detection is consistent among both women with intended and unintended pregnancies, which suggests preemptive change in alcohol use when planning a pregnancy is not typical.6 Previous studies on alcohol neglect or cannot capture information about timing of exposure in early pregnancy, which may obscure or underestimate risk of outcomes like spontaneous abortion.7 This limitation may fuel the misconception that adverse pregnancy outcomes are only associated with heavy consumption and that modest, occasional use is harmless.8, 9

Spontaneous abortion occurs in an estimated one in six recognized pregnancies10, 11 and can come at a great emotional cost.12 Alcohol use may increase risk of spontaneous abortion through several potential mechanisms: oxidative stress secondary to alcohol consumption may disrupt biochemical pathways involved in embryogenesis; exposure can hinder retinoic acid synthesis, thereby impacting epigenetic programming and cell lineage determination; alcohol use can alter maternal hormone levels impacting uterine receptivity.13 Studies of alcohol use and spontaneous abortion are often hindered by methodologic shortcomings such as recall bias and imprecision in determining gestational age at pregnancy loss.14 Many recruit participants during prenatal care, meaning enrollment takes place later in gestation than many spontaneous abortions occur. Others are vulnerable to selection bias due to recruitment methods that differ by pregnancy outcome. Prior studies routinely treat alcohol use as an unchanging exposure, which does not reflect pattern of use for most women.2, 5, 6 These factors leave women and care providers with limited access to data about how timing of alcohol use in pregnancy relates to spontaneous abortion.

In this prospective cohort, we had the opportunity to recruit participants representative of the general obstetric population. They were enrolled while planning a pregnancy or in early pregnancy and reported alcohol use both before and after any change in drinking. Our primary objective was to incorporate information about week-by-week alcohol use in measures of spontaneous abortion risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

With institutional review board approval, we recruited women early in pregnancy or planning a pregnancy into Right from the Start (RFTS), a prospective cohort. Women were enrolled between 2000 and 2012 from eight metropolitan areas in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.15 Recruitment materials were distributed through businesses, community groups, public advertising, direct mail, and prenatal care providers. Eligibility required participants to be age 18 years or older, English- or Spanish-speaking, no use of fertility treatments, and intention to carry pregnancy to term. Participants were enrolled prior to twelve completed weeks of gestation (median gestational age at enrollment, 47 days; inter-quartile range [IQR], 38–58; n=5,353) and gave informed consent. Women intending to become pregnant were provided free pregnancy tests for up to six months and enrolled at first positive pregnancy test.

Participants completed an intake interview at baseline and a computer-assisted telephone interview during the first trimester. Interviews collected information about demographics, medical history, reproductive history, lifestyle, and health behaviors. Participants had a transvaginal research ultrasound in the first trimester. The median gestational age of ultrasound was 58 days (IQR: 49–69 days).

Exposure

During the first trimester interview, participants provided detailed information about alcohol consumed in the past four months (Appendix). This window was selected to capture alcohol exposure immediately prior to pregnancy and through the first trimester. Participants reported whether they altered alcohol use during this period, date of change in use, and frequency, amount, and type of alcohol consumed before and after change, and number of binge episodes defined as consumption of more than four drinks in an episode. Gestational age at change was determined using self-reported last menstrual period (LMP), which is a validated and reliable dating method in this cohort.16 We used self-reported LMP for gestational dating for all study participants because ultrasound-based dating often underestimates gestational age in pregnancies that go on to end in loss. Number of drinks per week was calculated for before and after change and was evaluated as both a continuous and categorical measure (unexposed, ≤ 1 drink/week, 1.01–2 drinks/week, 2.01–4 drinks/week, >4 drinks/week). Beverage type was categorized as wine, beer, and/or liquor (consumed alone or in mixed drinks).

Outcome

Participants provided pregnancy status at 20–25 weeks from LMP. Self-reported pregnancy outcome was corroborated by information abstracted by trained study personnel from vital records, birth certificates, and medical records. Spontaneous abortion was defined as loss of pregnancy prior to 20 completed weeks’ gestation. Pregnancies ending in spontaneous abortion were compared to those surviving past 20 weeks’ gestation (live births and stillbirths) and participants with an unknown pregnancy outcome were censored at date of last study contact. We defined timing of pregnancy outcome among women with spontaneous abortion using two approaches: gestational age at spontaneous abortion and gestational age at arrest of development estimated using features observed on research ultrasound prior to loss.14 Gestational age at arrest of development was estimated using features observed on research ultrasound prior to loss, which was not was not available for 28.6% of participants who had a pregnancy that ended in spontaneous abortion (185/645). Since the distribution of gestational age at arrest differs by gestational age at spontaneous abortion, we assigned gestational age at arrest of development for women without a research ultrasound through random sampling of observed values of gestational age at arrest among women who had a spontaneous abortion in the same gestational week.

Statistical analysis

We used two main modeling approaches to quantify risk associated with alcohol use in pregnancy since timing of alcohol exposure may influence risk in multiple ways. First, we considered alcohol exposure by gestational week of exposure. Second, we evaluated how duration of alcohol exposure relates to risk.

Gestational age-specific exposure

Timing of exposure during pregnancy maps to embryologic development and thus informs risk, so we examined gestational week-specific effects of alcohol use. We performed separate logistic regressions to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for spontaneous abortion and alcohol exposure (yes/no) in each gestational week of the first trimester. Participants who did not use alcohol during pregnancy were counted as unexposed for all weeks and participants who did not change consumption or who only altered amount were considered exposed for all weeks. Participants who stopped using alcohol during the first trimester were classified as exposed in weeks prior to reported change and unexposed thereafter. Participants were included in week-specific models if they had not yet had a loss or been censored by the beginning of the week.

To evaluate the role of amount of alcohol consumed, we quantified the association between spontaneous abortion risk and number of drinks per week in four developmental windows in which teratogens are expected to confer risk through different mechanisms: peri-implantation (gestational weeks one through four), early embryonic (gestational weeks five through seven), late embryonic (gestational weeks eight through ten), and fetal (gestational weeks eleven and twelve).17 We performed separate logistic regressions for amount of alcohol consumed and spontaneous abortion risk for each window. Logistic regression model fit was assessed using Pearson goodness-of-fit test and Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Duration of exposure

We also considered duration of alcohol use during pregnancy may drive risk. We used extended Cox survival models to measure the association between spontaneous abortion and duration of alcohol use, operationalized as number of days between LMP and time t or gestational age at cessation of alcohol use, whichever came first. If a participant reported continuing alcohol use, duration of exposure accumulated until the first trimester interview. We present adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) associated with each additional week of use. Participants contributed time in the model from day of enrollment through 20 weeks’ gestation, arrest of development, or loss to follow up, whichever came first. Left truncation based on gestational age at enrollment allowed us to more precisely estimate spontaneous abortion risk by taking into account a subject had an ongoing pregnancy at cohort entry.18 Information about duration of exposure was updated in the model for each gestational day. Once a participant entered the cohort, the cumulative number of days exposed during pregnancy was reflected in the model, thus incorporating information about exposure that occurred prior to cohort entry while protecting for immortal time bias by not counting events that could not be observed. Given the varying amount of congeners,19 such as acetaldehyde, in different alcohols, we also evaluated risk associated with each additional week of exposure by beverage type in a secondary analysis.

Commonalities between approaches

Adjusted models included covariates selected a priori based on a directed acyclic graph of known or suspected relationships with alcohol consumption and spontaneous abortion risk:20 maternal age (years, spline), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white; non-Hispanic black; other), education (high school or less; some college; college or more), cigarette use (never smoker or distant quit [more than four months before first trimester interview]; recent quit or current smoker), pregnancy intention (intended; unintended),21 and parity (nulliparous; one prior birth; two or more prior births).

We enrolled 6,105 women and data from 5,353 were eligible for analysis (Figure 1). Participants who were excluded because they were missing data for one or more variables in the covariate set were younger and more likely to be black and have an unintended pregnancy than participants with complete data (n=71; Table A.1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study population derivation.

We performed a series of sensitivity analyses to determine robustness of results: analyses were repeated with pregnancy endpoint for losses defined as gestational age at spontaneous abortion as opposed to gestational age at arrest of development, with participants without a research ultrasound excluded, and with women who reported binge drinking excluded. We tested for effect modification by maternal body mass index (continuous) and smoking status using the likelihood ratio test for the inclusion of interaction terms. In a secondary analysis, we used Cox proportional hazard models to measure the association between number of binge episodes (none, 1–3, ≥4) and spontaneous abortion.

We used two-sided tests with a significance level of 0.05. Threshold for significance was Bonferroni-corrected by a factor equal to the number of tests performed in the hypothesis. Analyses were performed in Stata (Version 14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Among 5,353 women, 14.1% reported never using alcohol, 36.2% quit prior to LMP, 44.3% quit after LMP, and 5.4% continued use. Among 2,926 women who reported a change in alcohol exposure within the month prior to conception or during the first trimester, 91.5% quit using alcohol, 8.0% decreased use, and 0.5% increased use. Median gestational age at change was 29 days (IQR, 15–35 days) and 41.0% of participants who reported a change altered use within three days of a positive pregnancy test (1,214/2,962). Higher maternal age, household income, level of education, prenatal vitamin use, and illicit drug use were associated with alcohol exposure during pregnancy (Table 1). Non-Hispanic white women, nulliparous women, and smokers were more likely to be exposed to alcohol during pregnancy than their counterparts. Participants who were exposed to alcohol consumed a median of two drinks per week at the onset of pregnancy (IQR, 1–4 drinks per week). At least one binge episode during the periconception period or first trimester was reported by 11.0% of women reported (591/5,349). Median number of binge episodes was two (IQR, 1–4) and 10.3% of participants who binged reported ten or more episodes (61/591).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by alcohol use during pregnancya

| Characteristic | No Alcohol Use (n=2,691) | Alcohol Use (n=2,662) | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, No. (%), years | ||||

| <25 | 623 (23.2) | 418 (15.7) | 1.00 | Referent |

| 25–29 | 962 (35.7) | 880 (33.1) | 1.36 | 1.17–1.59 |

| 30–34 | 784 (29.1) | 936 (35.2) | 1.78 | 1.52–2.08 |

| ≥35 | 322 (12.0) | 428 (16.1) | 1.98 | 1.64–2.40 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,723 (64.0) | 2,052 (77.1) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 634 (23.6) | 353 (13.3) | 0.47 | 0.40–0.54 |

| Other | 334 (12.4) | 257 (9.7) | 0.65 | 0.54–0.77 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||

| High school or less | 586 (21.8) | 340 (12.8) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Some college | 520 (19.3) | 442 (16.6) | 1.47 | 1.22–1.76 |

| College or more | 1,585 (58.9) | 1,880 (70.6) | 2.04 | 1.76–2.37 |

| Household income, No. (%) | ||||

| ≤ $40,000 | 967 (35.9) | 638 (24.0) | 1.00 | Referent |

| $40,001-$80,000 | 972 (36.1) | 967 (36.3) | 1.51 | 1.32–1.72 |

| > $80,000 | 647 (24.0) | 986 (37.0) | 2.31 | 2.01–2.66 |

| Missing | 105 (3.9) | 71 (2.7) | ||

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| Married or cohabitating | 2,395 (88.4) | 2,401 (90.2) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Other | 296 (11.6) | 261 (9.8) | 0.88 | 0.74–1.05 |

| Parity, No. (%) | ||||

| Nulliparous | 1,149 (42.7) | 1,414 (53.1) | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1 prior delivery | 984 (36.6) | 869 (32.6) | 0.72 | 0.64–0.81 |

| 2+ prior deliveries | 558 (20.7) | 379 (14.2) | 0.55 | 0.47–0.64 |

| Prior spontaneous abortion, No. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 2,020 (75.1) | 2,115 (79.5) | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1 | 518 (19.2) | 443 (16.6) | 0.82 | 0.71–0.94 |

| ≥2 | 153 (5.7) | 104 (3.9) | 0.65 | 0.50–0.84 |

| BMI, No. (%), kg/m2 | ||||

| <18.5 | 67 (2.5) | 66 (2.5) | 0.87 | 0.62–1.24 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1,334 (49.6) | 1,505 (56.5) | 1.00 | Referent |

| 25–29.9 | 645 (24.0) | 610 (22.9) | 0.84 | 0.73–0.96 |

| ≥30 | 607 (22.6) | 460 (17.3) | 0.67 | 0.87–0.77 |

| Missing | 38 (1.4) | 21 (0.8) | ||

| Smoking status,b No. (%) | ||||

| Never or distant quit | 2,454 (91.2) | 2,266 (85.1) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Current or recent quit | 237 (8.8) | 396 (14.9) | 1.81 | 1.53–2.15 |

| Pregnancy Intention, No. (%) | ||||

| Intended | 1,983 (73.7) | 1,940 (72.9) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Not intended | 708 (26.3) | 722 (27.1) | 1.04 | 0.92–1.18 |

| Prenatal vitamin use,c No. (%) | ||||

| No | 109 (4.1) | 64 (2.4) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yes | 2,582 (95.9) | 2,598 (97.6) | 1.71 | 1.25–2.34 |

| Illicit drug use,c No. (%) | ||||

| No | 2,599 (96.6) | 2,400 (90.2) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yes | 92 (3.4) | 262 (9.8) | 3.08 | 2.42–3.94 |

| Intimate partner violence,c No. (%) | ||||

| No | 2,624 (97.5) | 2,579 (96.9) | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yes | 62 (2.3) | 79 (3.0) | 1.30 | 0.93–1.82 |

| Missing | 5 (0.2) | 4 (0.15) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Alcohol use defined as exposure past last menstrual period

Quitting within the four months prior to the end of first trimester interview is considered a recent quit; quitting before that time is considered a distant quit

Any history during the four months prior to the first trimester interview

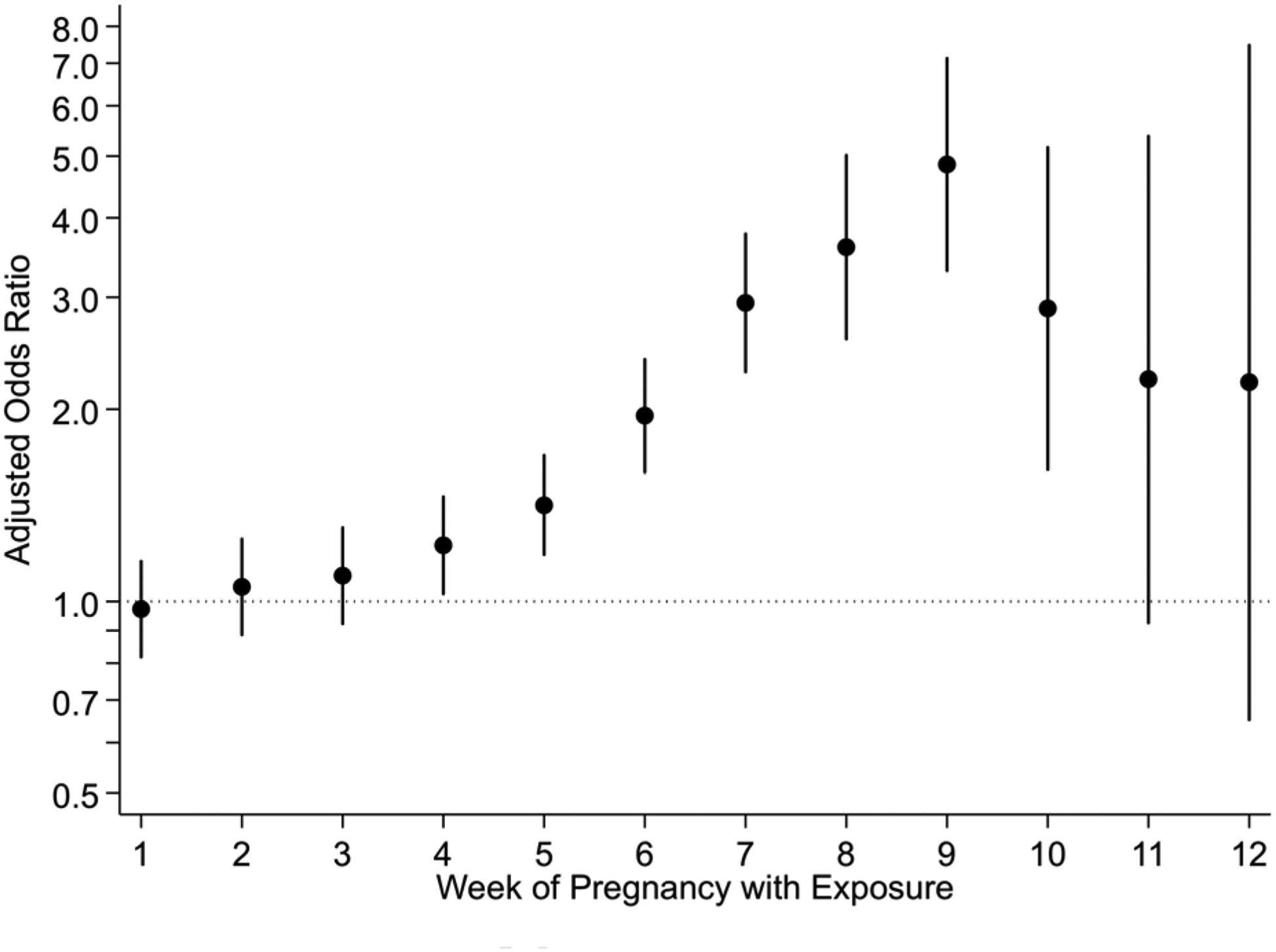

Twelve percent of pregnancies ended in spontaneous abortion (645/5,353). When considering week-specific exposure, alcohol use in gestational weeks five through ten was associated with spontaneous abortion after adjusting for multiple comparisons (aORs range, 1.42 to 4.85; Figure 2; Table A.2). Risk peaked for exposure in week nine of gestation (aOR, 4.85; 95% CI, 3.30–7.13). These results were consistent between the two approaches used for defining timing of outcome (Figure A.1) and when excluding participants who reported binge drinking. A dose-response trend was not detected in any developmental window (Table A.3).

Figure 2.

Risk of spontaneous abortion by gestational week with alcohol exposure (n=5,353). Pregnancy endpoint defined as gestational age at arrest of development. Estimates adjusted for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, parity, smoking status, and pregnancy intention. Weeks five through ten are significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-corrected with a factor of 12).

Each additional week of alcohol exposure during pregnancy was associated with an 8% relative increase in risk of spontaneous abortion compared with risk among women who were unexposed (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04–1.12; Table 2). Participants who were exposed to alcohol up until 29 days of gestation (the median gestational age of alcohol use cessation in the cohort) had a 37% greater risk of spontaneous abortion relative participants who were unexposed (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.18–1.60). Alcohol use in the lowest exposure category (≤ one drink per week) was associated with elevated risk in a way that was not different than estimates for higher levels of exposure (Table 2). Estimates did not vary by alcohol type (p-value 0.99, Wald test) or when excluding participants who reported binge drinking. Estimates did not differ when excluding pregnancies ending in spontaneous abortion without a research ultrasound (Table A.4) or when defining pregnancy endpoint as gestational age at spontaneous abortion (Table A.5).

Table 2.

Risk of spontaneous abortion associated with each additional week of alcohol use during pregnancya

| Alcohol Use Characteristic | Births (n=4708) | Spontaneous abortions (n=645) | Crude HR | 95% CI | Adjusted HRb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | Per additional week | Per additional week | |||

| Any Use | ||||||

| No | 2,367 (50.3) | 324 (50.2) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yesc | 2,341 (49.7) | 321 (49.8) | 1.09 | 1.05–1.13 | 1.08 | 1.04–1.12 |

| Amount at LMPd | ||||||

| Unexposed | 2,367 (50.3) | 324 (50.2) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| ≤ 1 drink/weekc | 931 (19.8) | 120 (18.6) | 1.09 | 1.05–1.14 | 1.08 | 1,04–1.13 |

| 1.01–2 drinks/week | 449 (9.5) | 67 (10.4) | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 |

| 2.01–4 drinks/week | 440 (9.3) | 60 (9.3) | 1.05 | 1.00–1.10 | 1.05 | 1.00–1.10 |

| > 4 drinks/week | 521 (11.1) | 74 (11.5) | 1.02 | 0.97–1.07 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 |

| Alcohol Typee | ||||||

| Winec | 1,545 (32.8) | 201 (31.2) | 1.07 | 1.03–1.11 | 1.07 | 1.02–1.11 |

| Beerc | 1,089 (23.1) | 138 (21.4) | 1.07 | 1.02–1.12 | 1.07 | 1.02–1.12 |

| Liquor | 858 (18.2) | 106 (16.4) | 1.03 | 0.97–1.09 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.10 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Alcohol modeled as a time-varying exposure for duration of use, left truncation based on gestational age at enrollment.

Adjusted for maternal age (continuous, spline), race/ethnicity, education, parity, smoking status, and pregnancy intention.

Significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-corrected with a factor of four for amount consumed and three for alcohol type).

Categories reflect level of alcohol consumption prior to change in use, duration defined as pre-change use.

Alcohol type categories do not total 100% since they are not mutually exclusive. Women who reported alcohol exposure in pregnancy but did not provide alcohol type are excluded from this analysis (n=30). Referent group is women unexposed to alcohol.

We did not observe modification of the association between alcohol use and spontaneous abortion by maternal body mass index or smoking status. Number of binge episodes was not associated with spontaneous abortion risk (zero episodes [referent]; 1–3 episodes aHR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.48–1.15; ≥4 episodes aHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.43–1.80) and inclusion of binge drinking in the main models did not alter findings. Any illicit drug use within four months leading up to the first trimester was reported by 6.6% of participants. Of the participants that reported illicit drug use, 84.2% reported marijuana as only exposure (298/354). Intimate partner violence within the four months prior to the first trimester interview was reported by 2.6% participants and physical harm was reported by 1.3% of participants (n=9 did not respond). Including illicit drug use and intimate partner violence as covariates in the adjusted estimates did not alter results.

COMMENT

Principal Findings

In this prospective, community-recruited cohort, timing of alcohol use is a key determinant of spontaneous abortion. Alcohol exposure occurred in half of pregnancies, with many participants not changing use until a positive pregnancy test. Each additional week of alcohol use in the first trimester was associated with a cumulative increase in risk of spontaneous abortion and risk was most strongly related to exposure in weeks five through ten of pregnancy. This window aligns with the embryonic stage of development, when organogenesis is occurring and pregnancy is most vulnerable to insults.22, 23 These findings persisted when excluding women who reported binge drinking.

Women who were older than 35, white, college-educated, and from high-income households were most likely to use alcohol. Although this is not the population generally flagged for high-risk behaviors, these demographics are consistently linked with alcohol use during pregnancy.1, 5, 24, 25 Clinical biases may result in these women being overlooked for risk counseling even though this group is at the greatest risk for modest, continued alcohol use.

Results in Context

Prior studies of alcohol exposure and spontaneous abortion risk are limited by methods for ascertaining and modeling exposure (Appendix 2).7 Many define exposure as alcohol use after pregnancy recognition. In RFTS, this definition misclassifies 44.3% of participants as unexposed. Others calculate an across-pregnancy average dose or describe pre-pregnancy alcohol use and its associated risk separately. An across-pregnancy average dose neglects that exposure is likely concentrated in early pregnancy. Evaluating “pre-pregnancy” exposure separately without considering how long use persists disregards that risk may be tied to gestational age at exposure. Alcohol use typically occurs prior to pregnancy detection and rapidly tapers thereafter. Therefore, most exposure co-occurs with the first stages of embryo development. Our results suggest timing of exposure is critical in understanding spontaneous abortion risk.

Strengths and Limitations

Before considering the implications of these findings, let us audit the level of confidence we should have in the results. We relied on self-report to determine alcohol use since no sufficiently sensitive and specific biomarker for alcohol exposure exists.26 Social desirability bias, or responding in a way deemed favorable by others, may lead women to underreport alcohol use during pregnancy.27, 28 We attempted to minimize this bias by conducting telephone interviews in a nonclinical and confidential setting using questionnaires with nonjudgmental wording and unknown interviewers. Prevalence of alcohol use at the onset of pregnancy in this cohort aligns with national data about exposure among nonpregnant, reproductive-aged women,5, 29 which provides reassurance social desirability bias did not unduly suppress reporting about presence of alcohol exposure.

Assessment of alcohol exposure followed loss for 67.2% of spontaneous abortions (436/649), allowing potential for recall bias.30 However, the proportion of women with losses who reported alcohol exposure during pregnancy did not differ by interview timing before or after loss (chi-squared p-value, 0.78) and gestational age at change in alcohol consumption was similar between the groups (median 31 days versus 32 days; Wilcoxon rank-sum p-value 0.36).

We did not observe a dose-response relationship between alcohol exposure and risk. While many biological relationships operate on a dose-dependent gradient, timing of alcohol use may drive spontaneous abortion risk with a threshold effect observed at low levels of exposure. In fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, a dose-response relationship is not always the rule.31, 32 Facial abnormalities characteristic of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder can be observed for low levels of alcohol use if exposure occurs when neural crest cells are migrating to form facial structures33 and changes in neonatal brain activity are observed with low levels of prenatal alcohol exposure.34 Alternatively, imprecision or bias in reporting amount of alcohol consumed may obscure a dose-dependent effect. Since alcohol use during pregnancy is stigmatized, information about amount consumed may be more vulnerable to reporting biases than responses about mere presence or absence of exposure. Additionally, misconceptions about size and alcohol content of a standard drink may lead to error in earnest reporting.

RFTS prioritized early recruitment of pregnancies to capture as many spontaneous abortion events as possible: 25.8% of participants entered the study prior to conceiving and 71.6% enrolled prior to seven weeks’ gestation. The proportion of participants who were exposed to alcohol in early pregnancy and timing of change in alcohol use was similar when comparing women who enrolled prior to conception to those who enrolled in the first trimester and results are unchanged when excluding participants who were enrolled prior to conception. Recruitment prior to conception or initiation of prenatal care enabled earlier enrollment than clinic-based studies. While this is an improvement over many studies of spontaneous abortion, losses occurring very early in gestation are inevitably underrepresented in this sample. We truncated time prior to enrollment in survival analyses to account for a participant having an ongoing pregnancy at study entry. Risk associated with alcohol use in the first weeks of pregnancy may be higher than estimated if unobserved early losses were highly associated with alcohol exposure.

Since this cohort required early enrollment, this study also has a higher proportion of planned pregnancies than the general population (73% versus 51%).21 The proportion of participants exposed to alcohol at pregnancy onset and timing of change in drinking was similar for participants with intended and unintended pregnancies, indicating planned pregnancies do not necessarily involve preparatory changes in alcohol use. Forty percent of women who were exposed reported quitting alcohol use within three days of a positive pregnancy test.

Less than one percent of participants reported a history of type 1 or type 2 diabetes and results were unchanged when diabetes was included in the adjusted model. A priori we determined there would be insufficient power to address other medical conditions associated with early pregnancy loss, such as infection or maternal anti-phospholipid syndrome. These conditions are rare and unlikely to influence findings of a large cohort. When limiting the analysis to women who had at least one prior live birth, and therefore proven capacity for a successful pregnancy, results were unchanged.

Conclusions and Implications

Studies not accounting for alcohol exposure in early pregnancy obscure the time-dependent effect of alcohol use and underestimate risk. In this prospective cohort, we find risk of spontaneous abortion accumulates with each successive week of alcohol use, even at low levels of consumption and when excluding binge drinking. These findings underscore the warning of no known safe amount of alcohol in pregnancy.35 Optimally, exposure would be completely prevented; still, half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended and abstaining from alcohol when planning a pregnancy is not typical. Since home pregnancy testing reliably detects pregnancy as early as four weeks’ gestation and alcohol use in weeks five through ten are most concerning for risk, there is a window of opportunity. Efforts to promote early pregnancy recognition and cessation of alcohol use are warranted to curtail risk of spontaneous abortion.

Supplementary Material

CONDENSATION.

Each additional week of alcohol exposure during the first trimester increases risk of spontaneous abortion, even at low levels of consumption and when excluding binge drinking.

AJOG AT A GLANCE.

A. Why was the study conducted?

Alcohol use is common in the first weeks of gestation prior to pregnancy detection.

Alcohol is routinely treated as an unchanging exposure, making information about how timing and duration of use relates to spontaneous abortion risk scarce.

B. What are the key findings?

Each additional week of alcohol exposure during the first trimester increases risk of spontaneous abortion, even at low levels of consumption and when excluding binge drinking.

Alcohol use in weeks five through ten of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion.

C. What does this study add to what is known?

Timing of alcohol use matters and each additional week of even modest consumption is associated with increased risk of spontaneous abortion.

An emphasis on early detection of pregnancy and cessation of alcohol use could curtail spontaneous abortions linked with exposure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development [R01 HD043883, R01 HD049675, F30 HD094345]; the American Water Works Association Research Foundation [2579]; the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [T32 GM07347]; and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [UL1 TR000445]. Funding sources had no role in study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in writing the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Study Sites: Chapel Hill, Durham, and Raleigh (North Carolina); Galveston (Texas); and Chattanooga, Knoxville, Nashville, and Memphis (Tennessee).

Disclosure Statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Green PP, McKnight-Eily LR, Tan CH, Mejia R, Denny CH. Vital Signs: Alcohol-exposed pregnancies: United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack C, Hutchinson D, Burns L, et al. Prenatal alcohol consumption between conception and recognition of pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2017;41:369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Keeffe LM, Kearney PM, McCarthy FP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of alcohol use during pregnancy: Findings from international multicentre cohort studies. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J. Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:E290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, Sniezek JE, Kanny D. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age: United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pryor J, Patrick SW, Sundermann AC, Wu P, Hartmann KE. Pregnancy intention and maternal alcohol consumption. Obstet Gyneco. 2017;129:727–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundermann AC, Zhao S, Young CL, et al. Alcohol use in pregnancy and miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2019; 43:1606–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meurk CS, Broom A, Adams J, Hall W, Lucke J. Factors influencing women’s decisions to drink alcohol during pregnancy: Findings of a qualitative study with implications for health communication. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland K, Mccallum K, Walton A. ‘I’m not clear on what the risk is’: Women’s reflexive negotiations of uncertainty about alcohol during pregnancy. Health Risk Soc 2016;18:38–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avalos LA, Galindo C, Li DK. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2012;94:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988;319;189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farren J, Mitchell-Jones N, Verbakel JY, Timmerman D, Jalmbrant M, Bourne T. The psychological impact of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update 2018;24:731–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalisch-Smith JI, Moritz KM. Detrimental effects of alcohol exposure around conception: Putative mechanisms. Biochem Cell Biol 2018;96:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundermann AC, Mukherjee S, Wu P, Velez Edwards DR, Hartmann KE. Gestational age at arrest of development: An alternative approach for assigning time at risk in studies of time-varying exposures and miscarriage. Am J Epidemiol 2019;188:570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Promislow JHE, Makarushka CM, Gorman JR, Howards PP, Savitz DA, Hartmann KE. Recruitment for a community-based study of early pregnancy: The Right From The Start study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2004;18:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman CS, Messer LC, Mendola P, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE. Comparison of gestational age at birth based on last menstrual period and ultrasound during the first trimester. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;22:587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore K, Persaud TVN, Torchia M. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology. 10th ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupont W. Statistical modeling for biomedical researchers: A simple introduction to the analysis of complex data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greizerstein HB. Congener contents of alcoholic beverages. J Stud Alcohol 1981;42:1030–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011;84:478–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yelin R, Ben-Haroush Schyr R, Kot H, et al. Ethanol exposure affects gene expression in the embryonic organizer and reduces retinoic acid levels. Dev Biol 2005;279:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Medical genetics: 1. Clinical teratology in the age of genomics. CMAJ 2002;167:265–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muggli E, O’Leary C, Donath S, et al. “Did you ever drink more?” A detailed description of pregnant women’s drinking patterns. BMC Public Health 2016;16:683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Floyd RL, Decoufle P, Hungerford DW. Alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition. Am J Prev Med 1999;17:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howlett H, Abernethy S, Brown NW, Rankin J, Gray WK. How strong is the evidence for using blood biomarkers alone to screen for alcohol consumption during pregnancy? A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;213:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey BA, Sokol RJ. Prenatal alcohol exposure and miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol Res Health 2011;34:86–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ernhart CB, Morrow-Tlucak M, Sokol RJ, Martier S. Underreporting of alcohol use in pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1988;12:506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alshaarawy O, Breslau N, Anthony JC. Monthly estimates of alcohol drinking during pregnancy: United States, 2002–2011. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2016;77:272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rockenbauer M, Olsen J, Czeizel AE, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT, Group TE. Recall bias in a case-control surveillance system on the use of medicine during pregnancy. Epidemiology 2001;12:461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA 2003;290:2996–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.May PA, Gossage JP. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Not as simple as it might seem. Alcohol Res Health 2011;34:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muggli E, Matthews H, Penington A, et al. Association between prenatal alcohol exposure and craniofacial shape of children at 12 months of age. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:771–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuffrey LC, Myers MM, Isler JR, et al. association between prenatal exposure to alcohol and tobacco and neonatal brain activity: Results from the Safe Passage Study. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e204714–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs) Alcohol use in pregnancy. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/alcohol-use.html (accessed Feb 7, 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.