Abstract

Purpose of review:

Here we review recent literature on the emerging role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) metabolism and its dysfunction via the enzyme CD38 in the pathogenesis of rheumatologic diseases. We evaluate the potential of targeting CD38 to ameliorate NAD+-related metabolic imbalance and tissue dysfunction in the treatment of systemic sclerosis (SSc), systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Recent findings:

In this review we will discuss emerging basic, pre-clinical and human data that point to the novel role of a CD38 in dysregulated NAD-homeostasis in SSc, SLE and RA. In particular, recent studies implicate increased activity of CD38, one of the main enzymes in NAD+-catabolism, in the pathogenesis of persistent systemic fibrosis in SSc, and increased susceptibility of SLE patients to infections. We will also discuss recent studies that demonstrate that a cytotoxic CD38 antibody can promote clearance of plasma cells involved in the generation of RA antibodies.

Summary:

Recent studies identify potential therapeutic approaches for boosting NAD to treat rheumatologic diseases including SSc, RA, and SLE, with particular attention to inhibition of CD38 enzymatic activity as a target. Key future directions in the field include the determination of the cell-type specificity and role of CD38 enzymatic activity versus CD38 structural roles in human diseases, as well as the indicators and potential side effects of CD38-targeted treatments.

Keywords: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), cluster of differentiation 38 (CD38), Systemic sclerosis (SSc), systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Introduction

Excessive morbidity and mortality in systemic fibrotic and inflammatory conditions remains a great concern for rheumatic diseases (1, 2). Although therapeutic options for some rheumatologic diseases continue to evolve, there remain many gaps in the understanding and optimal management of these diseases.

It is well accepted that diseases such as systemic scleroderma (SSc), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are multifactorial and involve the interaction between genetics, environmental factors, immune cells, and stromal cells (1-4). However, the precise mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of these diseases have not been completely understood.

One aspect that traditionally has not been considered in the pathogenesis of these diseases is the potential role of intermediary and energy metabolism. However, research on the molecular processes underlying rheumatic and immune mediated diseases in the last years have increasingly implicated the importance of intermediary metabolism in fibrosis, immune function and immune modulation.

Interestingly, recent data indicate that dysregulation of metabolism of the oxidation-reduction nucleotide nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) may play a key role in the pathophysiology of age-related health decline as well as multiple diseases states including SSc and SLE (5-14). Understanding the precise mechanisms that lead to dysregulation of NAD metabolism may contribute to the development of NAD-targeted therapies for fibrosis and autoimmunity. In particular, the widely expressed enzyme CD38 is the main NADase in mammalian tissues, and plays a key role in immune metabolism (5, 8, 9). Emerging data point to the possibility that CD38 may have an important role in the pathogenesis of SSc, SLE and RA (12, 13, 15, 16), and thus CD38-targeted therapies may represent a novel effective approach. However, much remains to be discovered before these approaches can be safely incorporated in our therapeutic arsenal.

Tissue NAD+-decline in the pathophysiology of human diseases.

Intracellular NAD+ levels decline in tissues during the aging process, and may also be a common mechanism of cell and tissue dysfunction in several acute and chronic disease states (5-13) (Table 1). Recent data from both animal models and human studies extend the role of cellular-tissue NAD+ decline to acute kidney injury, fetal malformations, mitochondrial myopathies, and rheumatic diseases such as SSc and SLE (10, 12, 13, 15-20). Furthermore, it has been proposed in both pre-clinical models and human studies that therapies aiming at increasing cellular NAD levels in vivo (so-called NAD-boosting therapies) could have beneficial effects in these diseases (10, 17, 21, 22) (Table 2).

Table 1:

Diseases whose pathophysiology has been associated with NAD/CD38 dysmetabolism in pre-clinical and/or human studies

| Pre-clinical studies | References | Human studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing loss | (53, 54) | Fetal malformation (VACTERL association) | (10) |

| Obesity and diabetes | (46, 55-57) | Acute Kidney Injury | (18, 20) |

| Kidney disease | (58) | Pellagra | (23, 24) |

| Heart disease | (59-62) | Mitochondrial myopathies | (17) |

| Non-alcoholic and Alcoholic fat liver disease | (46, 63, 64) | ||

| Muscular dystrophy | (65) | ||

| Mitochondrial myopathies | (66) | ||

| Neurodegeneration-related disease and Stroke | (6, 28, 31, 67, 68) | ||

| Aging, progeroid syndromes and Lifespan | (5-8, 69-71) | ||

| Cataract, Genetic macular degeneration | (72, 73) |

Table 2:

Strategies to promote NAD+-boosting.

| Type of NAD+-booster | Compound Name | Mechanism of Action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD precursors |

Niacin Nicotinamide Nicotinamide Riboside |

Vitamin B3 derivative NAD precursors | (21) |

|

NAD Analogous Covalent Inhibitors |

Ara-F-NMN phosphoester/C48 | Competitive Inhibition of NADase activity | (9, 74) |

|

Flavonoids Non-covalent inhibitors |

Apigenin | Competitive Inhibition of NADase activity | (9, 75) |

| Luteolinidin | |||

| Kuromanin | |||

|

Flavonoids Non-covalent inhibitors |

Rhein/K-Rhein | Uncompetitive Inhibition of NADase activity | (9, 76) |

|

4-amino-Quinolines Non-covalent inhibitors |

78c | Uncompetitive Inhibition of NADase activity | (11) |

| 1ah | (9, 77) | ||

| 1ai | |||

| Antibodies (IgG mAB) | Isatuximab | Cytotoxic Effect/Clearance of CD38+ cells and Allosteric Inhibition of NADase activity | (35, 78) |

| Antibodies (IgG mAB) | Daratumumab | Cytotoxic Effect/Clearance of CD38+ cells | (35, 79) |

| TAK-079 | (35, 80) | ||

| MOR-202 | (35, 78) |

The role of NAD+ in cellular function and pathophysiology

NAD(P) is a co-factor derived from vitamin B3 that is crucial for oxy-reduction reactions including glycolysis, fat acid oxidation/synthesis, and many others (5). In addition, NAD+ is also a substrate for enzymes involved in DNA-damage repair such as PARPs, as well as for epigenetic and metabolism regulatory enzymes such as the Sirtuins (NAD-dependent deacetylases) (5). Therefore, NAD+ has many functions and dysregulation of its homeostasis can lead to impairment in a broad range of fundamental cellular processes (5). In fact, pellagra, a disease resulting from severe vitamin B3 deficiency, leads to a decrease in tissue NAD-levels and consequent disruption in NAD-dependent cellular functions (23, 24). Pellagra is associated with dysfunction of multiple organ systems including the skin, gastrointestinal, immune and the central nervous system (25). Interestingly, recent studies indicate that a “functional” pellagra (leading to tissue and cellular NAD+-decline) is a common feature of many pathologic conditions.

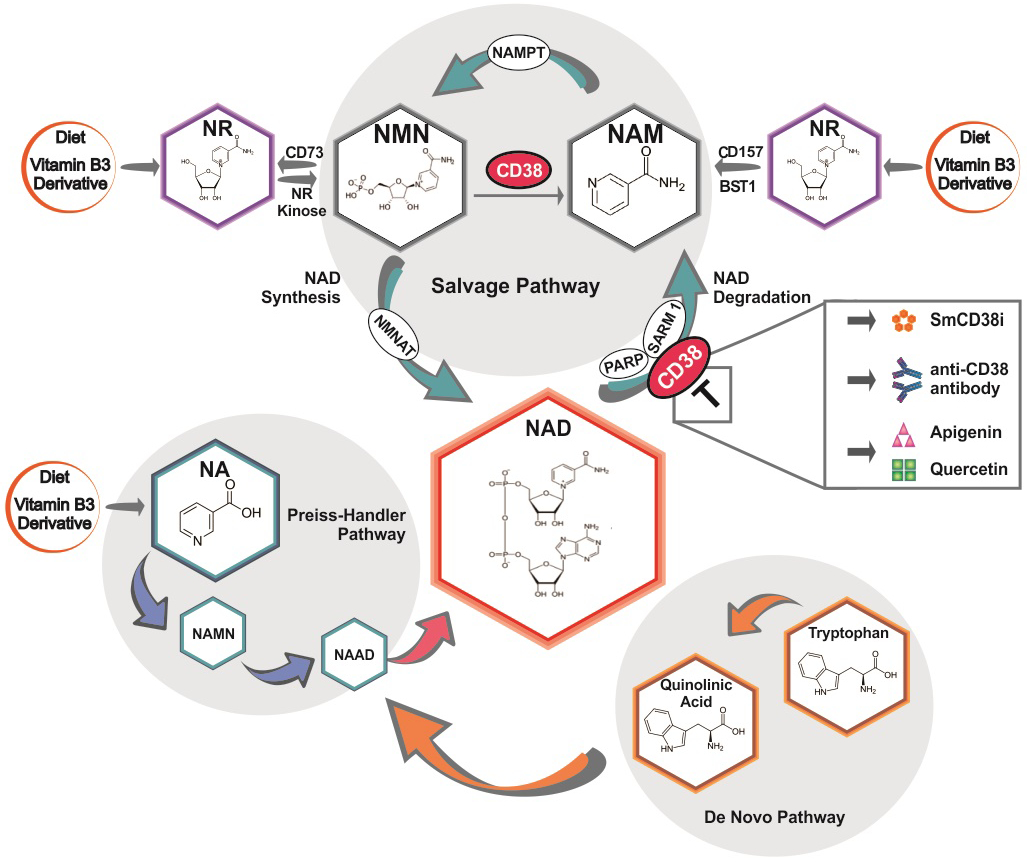

Thus, it has been proposed that NAD-depleted states could be pharmacologically approached by NAD+-boosting therapy (10, 21, 22). Our expanding understanding of NAD-metabolism has led to the characterization of both anabolic and catabolic pathways maintaining NAD homeostasis that can be targeted pharmacologically (Figure 1). These approaches include the vitamin B3 niacin and its derivatives, as well as inhibitors of the NAD-degrading enzymes CD38, PARPs and SARM1 (8, 9, 21) (Table 2).

Figure 1:

Scheme showing NAD synthesis and degradation pathways and possible interventions in NAD+-Boosting Therapies. smCD38i= small molecule CD38 inhibitors

The pharmacology of NAD metabolism and CD38 and their emerging pathogenic role in SSc and SLE

Emerging human studies confirm that NAD+-boosting with high doses of vitamin B3 may have beneficial effects in a variety of disease states (10, 17, 21, 22). A recent study demonstrated for the first time that in patients with mitochondrial myopathies, levels of NAD decline in both muscle and peripheral blood cells (17). Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that administration of vitamin 1 g B3 (Niacin) to these patients for several months leads to correction of NAD-decline and metabolomics profiles (17). Importantly, the authors also observed an improvement in muscle function and a decrease in liver fat accumulation, indicating that NAD-boosting with Niacin may provide an effective therapy for mitochondrial myopathy (17). Niacin has been used in humans for many decades, and except for flushing and rare cases of clinical relevant liver dysfunction, it is generally well tolerated and safe (26). In fact, Niacin has previously been proposed as a potential treatment for patients with Raynaud's disease (27). Another NAD precursor, Nicotinamide, has also been extensively used in humans (28). Significantly, Nicotinamide was shown to be effective in the chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancer in high risk patients, as well as in patients with increased risk for developing acute kidney injury (20, 29).

NAD-boosting in animals can also be achieved by supplementation with other forms of vitamin B3, including Nicotinamide riboside (NR) and Nicotinamide Mono Nucleotide (NMN), and by their reduced forms (21). However, whether these novels vitamin B3 derivatives are therapeutically superior to either Niacin or Nicotinamide has not yet been demonstrated. Furthermore, beneficial effects of high doses of vitamin B3 derivatives or of any NAD-boosting approach in patients with rheumatologic diseases have not been reported.

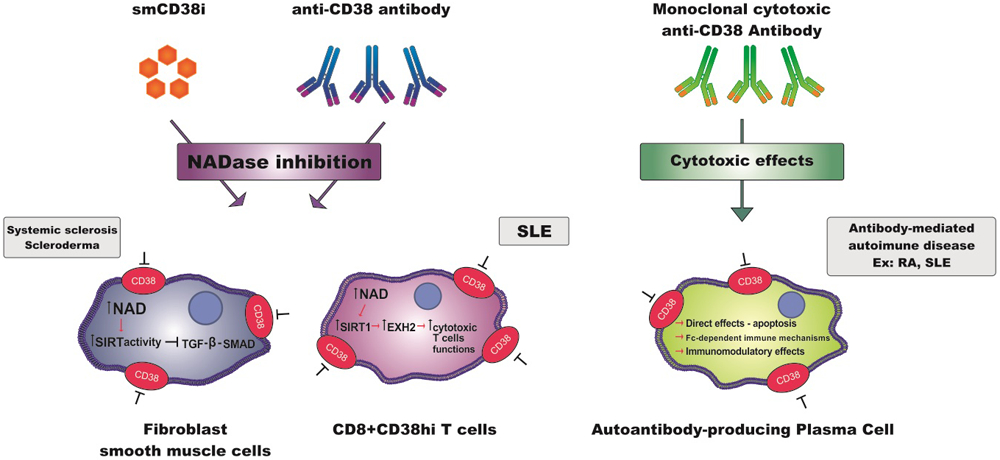

Therapeutic NAD+-boosting can also be achieved by inhibition of the NAD-consuming enzymes (8, 21). These include CD38, PARPs and SARM1 (5, 8, 21). SARM1 appears to be localized mostly in the neural compartment and may play a role in nerve injury during Wallerian degeneration (30, 31). On the other hand, PARPs are widely expressed poly-ADP-ribosyl polymerases involved in DNA-damage repair, and PARP inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of human cancers (32, 33). Finally, CD38 (cluster of differentiation 38) is a multifunctional enzyme that degrades NAD and modulates cellular NAD homeostasis (34). This ecto-NADase, most highly expressed on immune cells, has been implicated in several physiological and pathological states including aging, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, and inflammatory and infectious conditions (34). Recently, several classes of pharmacological tools targeting CD38 have been developed. These include enzymatic activity inhibitors such as natural products like Apigenin and Quercetin, small molecules such as thiazoloquin(az)olin(on)es, and specific inhibitory CD38 antibodies (9, 11). Moreover, CD38 has also been identified as a cell-surface marker in hematologic cancers such as multiple myeloma (MM), and the cytotoxic anti-CD38 antibody Daratumumab has been approved by FDA as therapy for MM (9, 35). Interestingly, recent studies indicate that CD38 may also play a role in dysfunction of NAD+-metabolism in both SSc and SLE (12, 13). Therefore, it has been proposed that therapeutically targeting CD38 or using an NAD-boosting approach could ameliorate fibrosis in SSc and decrease susceptibility to infections in patients with SLE (12, 13). Despite the fact that the optimal approach to target CD38 and NAD metabolism dysfunction in rheumatologic conditions remains to be fully elucidated, it is possible that in some of these, a cytotoxic antibody may be the best approach, while in others a CD38 enzymatic inhibitor may be superior. Notably, future research is needed to validate the role and cell type specificity of CD38 in the pathophysiology of these diseases, and to investigate the role of CD38-targeted therapy in pre-clinical studies.

CD38-mediated NAD metabolism in SSc.

Fibrosis is a dysregulated and prolonged repair process in which an excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components - among which collagen is the most predominant - occurs due to a severe or repetitive injury (1, 36). Unchecked fibrosis due to persistent myofibroblast activation leads to disruption of tissue architecture and ultimately to organ failure (1, 37). Fibrotic responses occur in a setting of chronic inflammation, which is defined as an immune response that persists for at least several months (38). Synchronous multiple organs fibrosis is a unique and defining characteristic of SSc and accounts for the morbidity and mortality in this disease (1, 36). The persistent accumulation of activated myofibroblasts is a defining feature of any kind of fibrosis (38, 39). However the factor(s) responsible for inducing the transition of different progenitor cells into myofibroblasts as well as their permanent activated state are disease-specific and largely unknown. In fact, the mechanisms that lead to fibrosis and tissue dysfunction in SSc are very complex and not fully understood (40). Recently, it was suggested that decrease in the function of the NAD-dependent deacetylases SIRT1 and SIRT3 could play a pathogenic role in SSc via loss of their repressive function regulating the pro-fibrotic TGF-β-SMAD pathway (41). Further, it was proposed that the loss of SIRT1 activity in SSc patients is mediated by a NAD-deficient state caused by an increased expression of the NAD-catabolic enzyme CD38 in their tissues (12). In fact, analysis of a public transcriptome dataset including 68 patients with SSc and 22 healthy controls identified increased CD38 mRNA expression in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc compared to both healthy control, and patients with limited cutaneous SSc (12). More importantly, CD38 mRNA expression positively correlated with both molecular markers of fibrosis and with the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS) (12). Furthermore, in pre-clinical models of SSc, boosting NAD+ levels by either administration of a CD38 inhibitor or supplementation with the vitamin B3 derivative, nicotinamide riboside (NR), ameliorated both lung and skin fibrosis (12). These effects were further augmented by the combination of the small molecule CD38 inhibitor and NR (12). The pathogenic role of CD38 in systemic fibrosis was further demonstrated by genetic deletion of CD38 (12). CD38 knockout mice were protected against bleomycin-induced skin and lung fibrosis compared to wild type animals (12). Mechanistically, CD38 inhibition prevented the TGF-β induced stimulation collagen synthesis of and alpha-smooth muscle actin cytoskeletal stress fiber formation (12) (Figure 2). Another enzyme involved in NAD-catabolism is NNMT. NNMT is also highly expressed in skin biopsies from patients with SSc, and may play a role in the cellular mechanisms of this disease (42). However, the pathogenic role of NNMT has not yet been explored in either animal models or patients with SSc. Interestingly, NNMT has been recently implicated in the induction of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) in ovarian cancer (42). In this study it was demonstrated that in ovarian cancer stromal cells, NNMT expression correlated with tissue fibrosis and poor outcomes, and was both necessary and sufficient for the function of CAF to support cancer growth and metastasis (42). Thus, aberrant NNMT expression or activity appears to be linked to multiple forms of pathological fibrosis. However, whether NNMT could also have a role in myofibroblast activation in SSc and thus represent a potential therapeutic target is an open question.

Figure 2:

Scheme showing mechanisms of CD38 inhibition and their activated molecular pathways in the pharmacologic approach of different rheumatologic diseases. smCD38i= small molecule CD38 inhibitors.

CD38 and the risk of infection in SLE patients.

SLE is a generalized auto-immune disease where dysfunctional T and B lymphocytes, and innate immune cells promote tissue injury and damage (2, 43). Immune dysfunction in SLE patients can also lead to a decreased capacity to fight both bacterial and viral infections (4). In fact, infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this disease (2). Increased susceptibility to infections in SLE is multifactorial and can be related to disease activity, environmental factors, and immune suppressive therapies (2, 4).

A recent study identified a dysfunctional population of endogenous T Cells that participate in increased infection susceptibility in SLE patients, and highlighted the fundamental pathogenic role of the NADase CD38 in these cells (13). The authors observed elevated CD38 expression on CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in a subset of SLE patients that exhibited increased infection frequency (Figure 2) (13). These Cd8+T cells demonstrated dysfunctional expression of several genes required for their cytotoxic activity (13). These included granzyme A, granzyme B, perforin, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) (13). The authors further demonstrated that deregulated expression of these genes in CD8+CD38hi T cells was mediated by a mechanism driven by CD38 NAD+-degrading enzymatic activity (13). In particular, this was mediated by the CD38-NAD+-SIRT1 axis described over 15 years ago (44).

The precise immunosuppressive role of the CD38-NAD+-SIRT1 axis in SLE T cells appeared to be mediated by a change in the acetylation of the enzyme EZH2. EZH2 is a methyl transferase that promotes epigenetic regulation of several genes (45). When acetylated, EZH2 is active and suppresses gene expression via the enzymatic trimethylation of histone H3K27(45). However, when de-acetylated, EZH2 is inactive and cannot suppress gene expression (13). One of the deacetylase enzymes involved in this process is the NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 (13). We have extensively demonstrated that the NADase CD38, by decreasing levels of NAD an obligate substrate for sirtuins, can suppress the activity of SIRT1 (11, 44, 46). Thus, in SLE patients, susceptibility to infections mediated by CD8+ CD38hi T cells appears to be driven by cellular NAD+-decline induced by CD38, and a subsequent decrease in SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of EZH2 (13) (Figure 2). Ultimately, this leads to EZH2 acetylation and subsequent activation, causing suppression of the cytotoxic functions of CD8+ CD38hi T cells (13).

Thus, this study proposed that the increased infection risk observed in SLE, which is promoted by dysfunctional cytotoxic T cells, may be ameliorated by inhibition of CD38-NADase activity leading to an increase in NAD levels, SIRT1 activation, and subsequent inhibition of the methyl transferase EZH2 (13). However, since it has been previously proposed that CD38 plays an active role in fighting bacterial infections in rodent macrophages and neutrophils (47) it is currently unclear whether inhibition of CD38 would decrease or increase the rate of infections in SLE patients. Resolving this interesting conundrum requires additional research.

The role of CD38 in antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases: targeting CD38 in plasma cells as a therapy for RA and SLE

Autoantibody-producing plasma cells (PCs) play a key role in the pathogenesis of antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases including RA and SLE (48). In general, autoantibodies participate in the pathophysiology of these diseases directly targeting the tissue or via formation of immune complexes (49). In RA, PCs are usually found in synovial biopsies, while in SLE patients, they are found in nephritic kidneys, leading to production of autoantibodies (16). Because these autoreactive PCs are long-lived and mostly resistant to conventional immunosuppressive treatments, they are interesting targets to be investigated as a new therapy for RA and SLE (50, 51). It has been previously demonstrated, using integrative analysis of synovial biopsies and PBMC in patients with RA and SLE, that CD38 is highly expressed in PCs in the peripheral blood compared to other immune cell populations (16). Interestingly, it has also been shown that PCs are reduced in MM patients treated with Daratumumab (15). Therefore, It has been postulated that Daratumumab could have an important effect in antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases via inducing cytotoxicity in autoreactive PCs (15) (Figure 2). A recent study evaluated autoantibodies in serum from MM patients, who received Daratumumab on monotherapy or combined with the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor Nivolumab (15). In six out of 41 patients in this study, autoantibodies were detected before treatment (15). In 5 out of these 6 patients Daratumumab treatment resulted in a sustained reduction of autoantibody titers, indicating the drug effectiveness in deplete autoreactive PCs (15). It has been demonstrated that the reduction of autoantibody levels is associated with clinical improvement as well as their reappearance with disease relapse (52). However, the analysis of autoantibodies levels may not be enough to investigate the effect of this anti-CD38 antibody in patients with autoimmune diseases. Therefore, additional studies are needed. Nonetheless, this study undoubtedly sets a new milestone to support the potential role of CD38 as a therapeutic target in patients with RA and SLE or other types of autoantibody-dependent autoimmune disorders.

Conclusion

NAD+ dysmetabolism has emerged as a common cause of tissue and cellular dysfunction in many conditions including aging, and acute and chronic diseases such as acute kidney injury and mitochondrial myopathy (5-14, 17, 18, 20). The role of NAD dysmetabolism has been investigated in pre-clinical animals models in many other conditions; these include age-related frailty, hearing loss, heart diseases, metabolic syndrome, and progeroid states just to mention a few (5-11, 14). Recently the pathogenic role of NAD dysmetabolism has been expanded to both fibrotic and autoimmune/inflammatory rheumatologic diseases including SSc, SLE and RA (12, 13, 15, 16, 19). The role of the CD38 has been explored in animals and/or human studies in these conditions (12, 13, 15, 16). Further studies will help to define the potential role of NAD-boosting and CD38 targeted therapies for these conditions. Importantly, extensive pre-clinical and clinical studies will be required to determine the safety and efficacy of these approaches in human diseases.

References:

- 1.Asano Y, Varga J. Rationally-based therapeutic disease modification in systemic sclerosis: Novel strategies. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2020;101:146–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsokos GC. Autoimmunity and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Immunology. 2020;21(6):605–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu E, Perl A. Pathogenesis and treatment of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31(3):307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grammatikos AP, Tsokos GC. Immunodeficiency and autoimmunity: lessons from systemic lupus erythematosus. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(2):101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chini CCS, Tarragó MG, Chini EN. NAD and the aging process: Role in life, death and everything in between. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;455:62–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verdin E NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2015;350(6265):1208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, et al. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013;155(7):1624–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CCS, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, et al. CD38 Dictates Age-Related NAD Decline and Mitochondrial Dysfunction through an SIRT3-Dependent Mechanism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chini EN, Chini CCS, Espindola Netto JM, de Oliveira GC, van Schooten W. The Pharmacology of CD38/NADase: An Emerging Target in Cancer and Diseases of Aging. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39(4):424–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi H, Enriquez A, Rapadas M, Martin EMMA, Wang R, Moreau J, et al. NAD Deficiency, Congenital Malformations, and Niacin Supplementation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):544–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarragó MG, Chini CCS, Kanamori KS, Warner GM, Caride A, de Oliveira GC, et al. A Potent and Specific CD38 Inhibitor Ameliorates Age-Related Metabolic Dysfunction by Reversing Tissue NAD. Cell Metab. 2018;27(5):1081–95.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi B, Wang W, Korman B, Kai Li, Wan Q, Wei J et al. Targeting CD38-Dependent NAD+ Metabolism to Mitigate Multiple Organ Fibrosis. 28 May 2020. ed. SSRN: : ISCIENCE-D-20-00897; 2020.This manuscript described for the first time a role for CD38 in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis.

- 13.Katsuyama E, Suarez-Fueyo A, Bradley SJ, Mizui M, Marin AV, Mulki L, et al. The CD38/NAD/SIRTUIN1/EZH2 Axis Mitigates Cytotoxic CD8 T Cell Function and Identifies Patients with SLE Prone to Infections. Cell Rep. 2020;30(1):112–23.e4.In this manuscript the authors elegantly demonstrate a role for the CD38-NAD-SIRT1 axis, initially described by us (40), in the pathogenesis of increased susceptibility to infections in SLE patients.

- 14.Katsyuba E, Romani M, Hofer D, Auwerx J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nature Metabolism. 2020;2(1):9–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frerichs KA, Verkleij CPM, Bosman PWC, Zweegman S, Otten H, van de Donk NWCJ. CD38-targeted therapy with daratumumab reduces autoantibody levels in multiple myeloma patients. Journal of Translational Autoimmunity. 2019;2:100022.In this recent manuscript the authors demonstrate that patients with Multiple myeloma treated with a CD38 targeted cytotoxic antibody, have suppression of autoantibodies related to rheumatoid arthritis.

- 16.Cole S, Walsh A, Yin X, Wechalekar MD, Smith MD, Proudman SM, et al. Integrative analysis reveals CD38 as a therapeutic target for plasma cell-rich pre-disease and established rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirinen E, Auranen M, Khan NA, Brilhante V, Urho N, Pessia A, et al. Niacin Cures Systemic NAD + Deficiency and Improves Muscle Performance in Adult-Onset Mitochondrial Myopathy. Cell Metab. 2020;31(6):1078–90.e5.This original article shows a pilot study that is a proof-of-principle of niacin effects on mitochondrial myopathy. The data implicate niacin as a promising treatment for mitochondrial myopathy patients who show NAD+ deficiency, but effects for other patient groups are still unknown.

- 18.Poyan Mehr A, Tran MT, Ralto KM, Leaf DE, Washco V, Messmer J, et al. De novo NAD+ biosynthetic impairment in acute kidney injury in humans. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(9):1351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyman AE, Atamas SP. Sirtuins and Accelerated Aging in Scleroderma. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(4):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulluck H, Hausenloy DJ. Modulating NAD+ metabolism to prevent acute kidney injury. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(9):1306–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajman L, Chwalek K, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):529–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chini EN. Of Mice and Men: NAD+ Boosting with Niacin Provides Hope for Mitochondrial Myopathy Patients. Cell Metabolism. 2020;31(6):1041–3.This editorial enlightens the most recent findings in NAD+ -boosting therapies in humans using the Vit B3 derivative Niacin.

- 23.Raghuramulu N, Srikantia SG, Rao BS, Gopalan C. Nicotinamide nucleotides in the erythrocytes of patients suffering from pellagra. Biochem J. 1965;96(3):837–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams AC, Hill LJ, Ramsden DB. Nicotinamide, NAD(P)(H), and Methyl-Group Homeostasis Evolved and Became a Determinant of Ageing Diseases: Hypotheses and Lessons from Pellagra. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2012;2012:302875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savvidou S Pellagra: a non-eradicated old disease. Clinics and practice. 2014;4(1):637-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, et al. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8(6):1245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ring EF, Bacon PA. Quantitative thermographic assessment of inositol nicotinate therapy in Raynaud's phenomena. J Int Med Res. 1977;5(4):217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fricker RA, Green EL, Jenkins SI, Griffin SM. The Influence of Nicotinamide on Health and Disease in the Central Nervous System. International journal of tryptophan research : IJTR. 2018;11:1178646918776658-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fania L, Mazzanti C, Campione E, Candi E, Abeni D, Dellambra E. Role of Nicotinamide in Genomic Stability and Skin Cancer Chemoprevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. The SARM1 Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor Domain Possesses Intrinsic NAD. Neuron. 2017;93(6):1334–43.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerdts J, Brace EJ, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. SARM1 activation triggers axon degeneration locally via NAD+ destruction. Science. 2015;348(6233):453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegler M, Oei SL. A cellular survival switch: poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation stimulates DNA repair and silences transcription. Bioessays. 2001;23(6):543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MK, Cheong HS, Koh Y, Ahn KS, Yoon SS, Shin HD. Genetic Association of PARP15 Polymorphisms with Clinical Outcome of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in a Korean Population. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20(11):696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogan KA, Chini CCS, Chini EN. The Multi-faceted Ecto-enzyme CD38: Roles in Immunomodulation, Cancer, Aging, and Metabolic Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Donk NWCJ, Usmani SZ. CD38 Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: Mechanisms of Action and Modes of Resistance. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volkmann ER, Varga J. Emerging targets of disease-modifying therapy for systemic sclerosis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2019;15(4):208–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Varga J. Understanding fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: shifting paradigms, emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;8(1):42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1028–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmoulière A, Varga J, et al. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(4):1340–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Distler JHW, Györfi AH, Ramanujam M, Whitfield ML, Königshoff M, Lafyatis R. Shared and distinct mechanisms of fibrosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(12):705–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei J, Ghosh AK, Chu H, Fang F, Hinchcliff ME, Wang J, et al. The Histone Deacetylase Sirtuin 1 Is Reduced in Systemic Sclerosis and Abrogates Fibrotic Responses by Targeting Transforming Growth Factor β Signaling. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(5):1323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eckert MA, Coscia F, Chryplewicz A, Chang JW, Hernandez KM, Pan S, et al. Proteomics reveals NNMT as a master metabolic regulator of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature. 2019;569(7758):723–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zharkova O, Celhar T, Cravens PD, Satterthwaite AB, Fairhurst AM, Davis LS. Pathways leading to an immunological disease: systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(suppl_1):i55–i66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aksoy P, Escande C, White TA, Thompson M, Soares S, Benech JC, et al. Regulation of SIRT 1 mediated NAD dependent deacetylation: a novel role for the multifunctional enzyme CD38. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349(1):353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gan L, Yang Y, Li Q, Feng Y, Liu T, Guo W. Epigenetic regulation of cancer progression by EZH2: from biological insights to therapeutic potential. Biomark Res. 2018;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbosa MT, Soares SM, Novak CM, Sinclair D, Levine JA, Aksoy P, et al. The enzyme CD38 (a NAD glycohydrolase, EC 3.2.2.5) is necessary for the development of diet-induced obesity. FASEB J. 2007;21(13):3629–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glaría E, Valledor AF. Roles of CD38 in the Immune Response to Infection. Cells. 2020;9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deane KD. Preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (autoantibodies): an updated review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(5):419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin F, Chan AC. B cell immunobiology in disease: evolving concepts from the clinic. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:467–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dörner T, Lipsky PE. Beyond pan-B-cell-directed therapy - new avenues and insights into the pathogenesis of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(11):645–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hiepe F, Radbruch A. Plasma cells as an innovative target in autoimmune disease with renal manifestations. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(4):232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bugatti S, Manzo A, Montecucco C, Caporali R. The Clinical Value of Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown KD, Maqsood S, Huang JY, Pan Y, Harkcom W, Li W, et al. Activation of SIRT3 by the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside protects from noise-induced hearing loss. Cell Metab. 2014;20(6):1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, Vann JM, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. Sirt3 Mediates Reduction of Oxidative Damage and Prevention of Age-Related Hearing Loss under Caloric Restriction. Cell. 2010;143(5):802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cantó C, Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Youn DY, Oosterveer MH, Cen Y, et al. The NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6):838–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshino J, Mills KF, Yoon MJ, Imai S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011;14(4):528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trammell SA, Weidemann BJ, Chadda A, Yorek MS, Holmes A, Coppey LJ, et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Opposes Type 2 Diabetes and Neuropathy in Mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guan Y, Wang S-R, Huang X-Z, Xie Q-H, Xu Y-Y, Shang D, et al. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide, an NAD(+) Precursor, Rescues Age-Associated Susceptibility to AKI in a Sirtuin 1-Dependent Manner. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017;28(8):2337–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Wang B, Fu X, Guan S, Han W, Zhang J, et al. Exogenous NAD(+) administration significantly protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat model. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(8):3342–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan XH, Hong X, Zhao N, Liu XH, Xiao YF, Chen TT, et al. CD38 promotes angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(8):1492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boslett J, Helal M, Chini E, Zweier JL. Genetic deletion of CD38 confers post-ischemic myocardial protection through preserved pyridine nucleotides. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;118:81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee CF, Chavez JD, Garcia-Menendez L, Choi Y, Roe ND, Chiao YA, et al. Normalization of NAD+ Redox Balance as a Therapy for Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;134(12):883–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gariani K, Menzies KJ, Ryu D, Wegner CJ, Wang X, Ropelle ER, et al. Eliciting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide repletion reverses fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2016;63(4):1190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.French SW. Chronic alcohol binging injures the liver and other organs by reducing NAD+ levels required for sirtuin's deacetylase activity. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2016;100(2):303–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryu D, Zhang H, Ropelle ER, Sorrentino V, Mázala DA, Mouchiroud L, et al. NAD+ repletion improves muscle function in muscular dystrophy and counters global PARylation. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(361):361ra139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cerutti R, Pirinen E, Lamperti C, Marchet S, Sauve AA, Li W, et al. NAD(+)-dependent activation of Sirt1 corrects the phenotype in a mouse model of mitochondrial disease. Cell Metab. 2014;19(6):1042–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park JH, Long A, Owens K, Kristian T. Nicotinamide mononucleotide inhibits post-ischemic NAD(+) degradation and dramatically ameliorates brain damage following global cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;95:102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wakade C, Giri B, Malik A, Khodadadi H, Morgan JC, Chong RK, et al. Niacin modulates macrophage polarization in Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2018;320:76–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Picciotto NE, Gano LB, Johnson LC, Martens CR, Sindler AL, Mills KF, et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation reverses vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress with aging in mice. Aging Cell. 2016;15(3):522–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H, Ryu D, Wu Y, Gariani K, Wang X, Luan P, et al. NAD+ repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science. 2016;352(6292):1436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scheibye-Knudsen M, Mitchell Sarah J, Fang Evandro F, Iyama T, Ward T, Wang J, et al. A High-Fat Diet and NAD+ Activate Sirt1 to Rescue Premature Aging in Cockayne Syndrome. Cell Metabolism. 2014;20(5):840–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams PA, Harder JM, Foxworth NE, Cochran KE, Philip VM, Porciatti V, et al. Vitamin B(3) modulates mitochondrial vulnerability and prevents glaucoma in aged mice. Science. 2017;355(6326):756–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koenekoop RK, Wang H, Majewski J, Wang X, Lopez I, Ren H, et al. Mutations in NMNAT1 cause Leber congenital amaurosis and identify a new disease pathway for retinal degeneration. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):1035–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwong AK, Chen Z, Zhang H, Leung FP, Lam CM, Ting KY, et al. Catalysis-based inhibitors of the calcium signaling function of CD38. Biochemistry. 2012;51(1):555–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kellenberger E, Kuhn I, Schuber F, Muller-Steffner H. Flavonoids as inhibitors of human CD38. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21(13):3939–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blacher E, Ben Baruch B, Levy A, Geva N, Green KD, Garneau-Tsodikova S, et al. Inhibition of glioma progression by a newly discovered CD38 inhibitor. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(6):1422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Becherer JD, Boros EE, Carpenter TY, Cowan DJ, Deaton DN, Haffner CD, et al. Discovery of 4-Amino-8-quinoline Carboxamides as Novel, Submicromolar Inhibitors of NAD-Hydrolyzing Enzyme CD38. J Med Chem. 2015;58(17):7021–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van de Donk N, Richardson PG, Malavasi F. CD38 antibodies in multiple myeloma: back to the future. Blood. 2018;131(1):13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.KA F, CPM V, PWC B, S Z, H O, NWCJ vdD. CD38-targeted therapy with daratumumab reduces autoantibody levels in multiple myeloma patients. Journal of Translational Autoimmunity. 2019;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smithson G, Zalevsky J, Korver W, Roepcke S, McLean L. CD38+ cell depletion with TAK-079 reduces arthritis in a cynomolgus collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model. The Journal of Immunology. 2017;198(1 Supplement):127.17. [Google Scholar]