Key points.

-

•

Pain in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is common, has many causes, and is often poorly managed.

-

•

Research and advocacy have largely focused on palliative care and increasing access to opioid analgesia; acute pain and chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) have received little attention.

-

•

Access to opioid analgesia is poor in many countries; increased availability could dramatically improve the management of acute pain and cancer pain.

-

•

CNCP contributes significantly to the global burden of pain, and more treatment options are needed.

-

•

Key areas for improving pain management in LMICs include advocacy, improving treatment availability, and education.

Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Describe the key pain management barriers in low- and middle-income countries.

-

•

Discuss the need for adequate availability and appropriate prescribing of opioid analgesics.

-

•

Explain the central role of education in improving pain management.

Globally, pain is an underdiagnosed and undertreated healthcare problem. Patients the world over are suffering from pain of all types—cancer and end-of-life pain, acute pain (including pain caused by surgery and injury), and chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP).

There is increasing recognition of the contribution of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) to the global burden of disease. Alongside this, there is a need to recognise the impact of inadequately managed pain. In many resource-poor environments, little or no treatment is provided—there is a ‘treatment gap’ between what could be done and what is actually being done.1 Because of this gap, there are many opportunities to dramatically improve pain management by using simple, cost-effective strategies. These strategies include education and improved availability of low-cost and effective treatments.

The scale of the problem

The WHO estimates that 5.5 billion people (more than 80% of the global population) do not have access to treatments for moderate to severe pain.2 Most of these people live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The global burden of pain has numerous aetiologies including surgery, trauma, childbirth, chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g. arthritis), non-specific low back pain, chronic postsurgical pain, diabetic neuropathy, and cancer. These causes of pain are common in both high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs. Other types of pain are more common in LMICs (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS)-related pain and pain caused by sickle cell disease).

Overall, there is a paucity of research regarding pain in LMICs. The majority of studies focus on pain treatment in the palliative care setting and on the availability of opioids. A very small number of articles focus on acute pain and CNCP.

There is little information on the impact of untreated pain in LMICs. However, alongside the physical and psychological effects, there may be serious economic and social consequences for an individual and their family because of low levels of state-funded healthcare and welfare.

Cancer pain and palliative care

In 2015, there were 17.5 million cancer cases worldwide and 8.7 million deaths from cancer.3 Moderate to severe pain caused by cancer is more common in LMICs.4 Frequently, patients with cancer present late and treatment options are more limited. In addition, effective analgesic treatments, especially morphine, may be unavailable.

Palliative care is not limited to the management of cancer pain. The Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life estimates that 20 million people are in need of palliative care because of HIV/AIDS, cancer, and other non-malignant progressive diseases.4 The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief (LCPCPR) widens this inclusion further, describing a new term of ‘serious health-related suffering’ (SHS), which includes pain and other symptoms in health conditions that are life-threatening or life-limiting.5 The Commission estimates that 25.5 million people die each year with SHS, and 80% of these people live in LMICs. In addition, a further 35.5 million people live with avoidable SHS but do not die.

The enormous burden of HIV/AIDS in LMICs results in a large pain management burden because of HIV neuropathy.4, 6 The availability of treatments for this type of pain may be very limited.

Acute pain

Common causes of acute pain include perioperative pain and trauma, pain in childbirth, and pain resulting from a sickle cell crisis.

Surgical disease and trauma account for almost 30% of the global burden of disease; however, 5 billion people out of the world's 7 billion population do not have access to safe surgical care and anaesthesia.7 This has major implications for the provision of pain treatment.

Firstly, acute pain from surgery or trauma is often poorly treated. For example, a survey of 149 postoperative patients in a teaching hospital in Nigeria found that 68.7% had moderate to unbearable pain at 24 h, and 51.7% at 48 h.8

Secondly, there is increasing recognition of the unmet surgical need worldwide and that surgical volumes are likely to increase during coming decades. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery estimates that 143 million additional procedures per year will be required to address this need.7 In 2015, the WHO called on member states to strengthen safe surgical care and anaesthesia.9 An inevitable consequence will be increased requirements for postoperative acute pain management.

Thirdly, the increased surgical volume will lead to more chronic postsurgical pain.10 There is limited research in this area, but Caesarean section and hernia repair surgeries account for a large proportion of operations in LMICs, and both are known to result in significant rates of chronic postsurgical pain.

Pain in childbirth is frequently untreated in LMICs, and approximately 110 million babies are born in LMICs each year. Frequently, there is an expectation amongst carers and women that pain during childbirth is inevitable, and this expectation is reinforced by cultural and religious expectations.11

Acute pain arising from sickle cell crisis may be acute-on-chronic pain and imposes an extra pain burden in many LMICs.12

CNCP

There is limited information about the prevalence and impact of CNCP in low-resource settings. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 119 publications in 28 LMICs found that the prevalence of chronic pain without clear aetiology in the general population was 34%.13 Types of pain included low back pain, neck pain, headache, musculoskeletal pain, joint pain, chronic pelvic/prostatitis pain, temporomandibular disorder, abdominal pain, fibromyalgia, and widespread pain. The review noted that known risk factors for chronic pain (e.g. psychological trauma, interpersonal violence, and low socio-economic status) are higher in LMICs than in HICs.

The global burden of chronic pain, regardless of cause, is described as large and growing, in parallel with the increasing burden of NCDs.13 There is likely to be a significant burden of chronic neuropathic pain, including diabetic neuropathy and post-amputation pain, and (as mentioned above) an increasing amount of chronic postsurgical pain.

Pain management barriers

There are many reasons why pain, of all types, may not be treated adequately. Key barriers include poor knowledge and attitudes about pain relief, and issues relating to access and use of medications, especially opioids. These barriers exist in HICs and LMICs but are compounded by resource constraints in LMICs.

Low prioritisation of pain relief

Unfortunately, pain management has often been given a low priority at global and government levels, and during the care of the individual patient. At a global level, there are many parallels with the low priority given by the WHO and governments to the development of surgical and anaesthesia services. For many decades, the main focus of the WHO has been combating communicable diseases. This is starting to change with an increase in the understanding of the contribution of NCDs to the global burden of disease. Pain, like surgery and anaesthesia, cuts across many disease categories and does not fit neatly with traditional approaches to health management at a global level.

The LCPCPR argues that palliative care and pain management are given a low priority because of a healthcare focus on extending life and productivity, instead of alleviating pain and increasing dignity at the end of life. Pain management may also be given a low priority at the hospital and individual patient care level. A number of factors contribute to this especially in resource-poor environments—low health worker numbers, outdated or incorrect attitudes about pain management, and poor knowledge about treatment options. In these environments, it may be easier not to ask about the presence of pain. The concept of pain as the fifth vital sign is an attempt to increase the awareness of pain as a symptom that should be actively sought and managed.

Patient expectations and attitudes

Unfortunately, in a resource-poor environment, patients may become fatalistic about the lack of adequate pain treatment. Low expectations may result from generalised health system deficiencies or specifically regarding pain relief. For example, in cancer pain, all modalities of treatment may be severely limited or non-existent—surgery, symptom control, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy—leading patients to have very limited expectations of pain treatment. Patients may have exhausted their financial resources seeking curative treatment, resulting in an inability to fund pain treatments.14 Similarly, postoperative pain may be seen as an inevitable part of having an operation. Pain during childbirth may be expected or even seen as necessary. In some cultures, enduring pain may be seen as a sign of strength.15

Staff knowledge and attitudes

Pain management education is often limited for doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers resulting in deficiencies in knowledge and poor attitudes towards the management of pain. Poor pain education is an issue for many parts of the world—HICs and LMICs.

A survey of 242 medical schools in 15 European countries found that fewer than 20% had dedicated compulsory pain teaching. Education, when provided, occurred within other subjects and tended to not use practical teaching methods.16 In a survey of doctors in 49 LMICs, 90% considered their undergraduate training in pain management to be inadequate, and 80% did not receive formal training. The survey also found that postgraduate training was very variable.1

The lack of pain education not only results in poor knowledge of treatment options but can also contribute to poor attitudes about the need for improved pain management. In addition, effective pain management often requires a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach requiring education for all members of the team.

Access to analgesic treatments

In many LMICs, the range of analgesic medications is very limited and the supply of medications may be intermittent or non-existent. Availability of opioid analgesics is often particularly problematic (see below) but there may also be very limited treatment options for neuropathic and other types of CNCP. Table 1 shows the relatively limited range of analgesic medications that are listed in the WHO's Model Lists of Essential Medicines (MLEM).17 Unfortunately, the presence of a medication on the MLEM does not guarantee its availability in many resource-poor environments.

Table 1.

Analgesic medications listed in the WHO's MLEM

| Non-opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications | |

| Aspirin | Suppository, tablet |

| Ibuprofen | Tablet |

| Paracetamol | Oral liquid, suppository, tablet |

| Opioid analgesics | |

| Codeine | Tablet |

| Morphine | Injection, oral liquid, tablet (immediate release), tablet (slow release) |

| Anticonvulsants, anti-epileptics | |

| Carbamazepine | Oral liquid, tablet |

| Sodium valproate | Oral liquid, tablet |

| Medicines used in mood disorders | |

| Amitriptyline | Tablet |

| General anaesthetics | |

| Ketamine | Injection |

| Nitrous oxide | Inhalation |

| Local anaesthetics | |

| Bupivacaine | Injection |

| Lidocaine | Injection |

| Lidocaine with adrenaline | Injection |

Other treatment modalities (e.g. regional analgesia, nerve blocks, physiotherapy, psychological treatments, and MDTs) are frequently unavailable. The lack of these modalities is particularly pertinent in CNCP, where traditional analgesic medications, especially opioids, may have limited efficacy.

Specific issues related to opioid analgesics

Morphine is inexpensive and listed as an essential medicine by the WHO. It has a particularly important role in the treatment of moderate to severe acute pain, and the treatment of cancer pain. It is estimated that more than 90% of the world's opioids are consumed in a small group of rich countries accounting for less than 20% of the world's population.4 LMICs are not only faced with an increased burden of disease because of advanced cancer, HIV, and a range of other conditions that may respond to opioid treatment, but they are also deprived of one of the key treatment options for pain. The LCPCPR describes the situation as the ‘access abyss’.

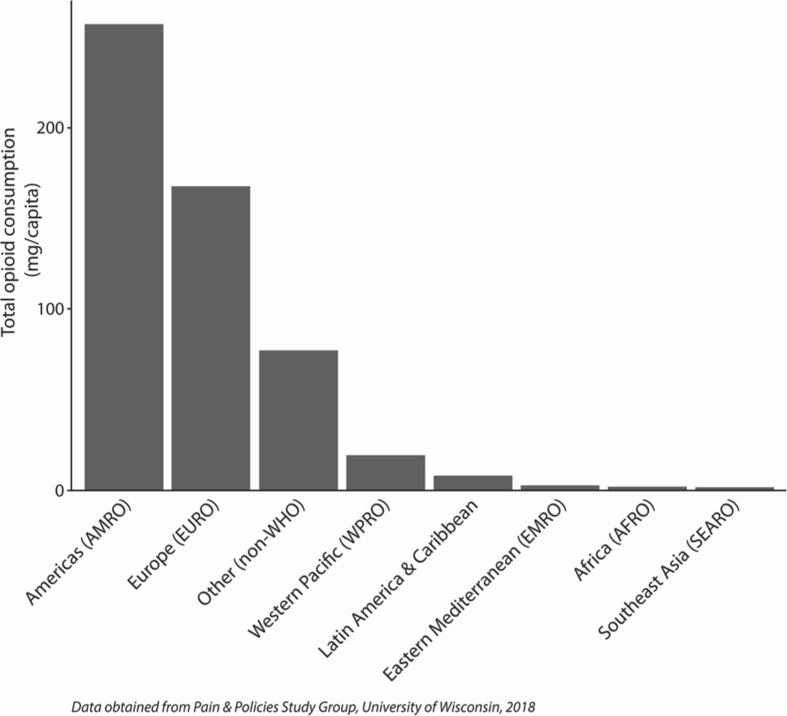

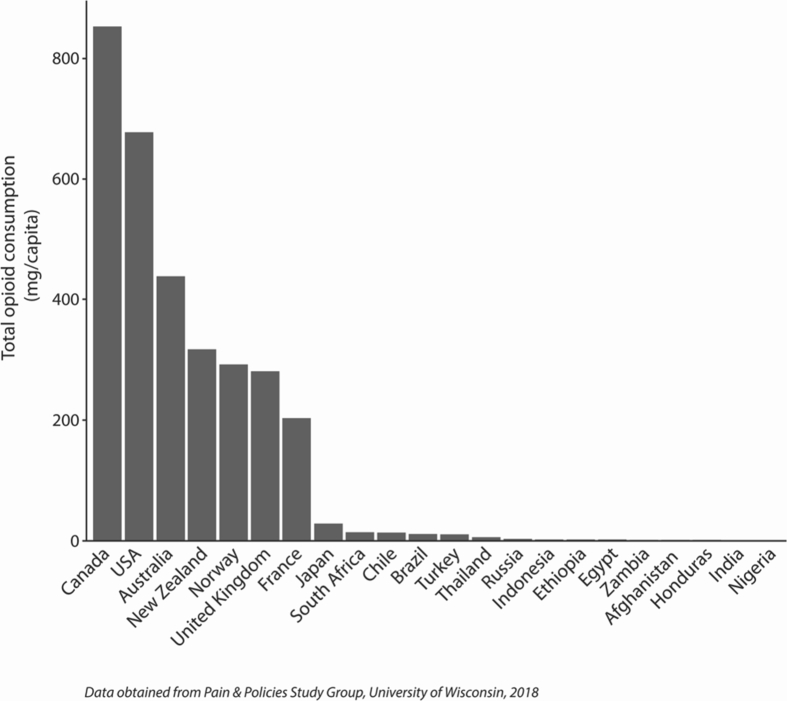

Disparities in global opioid consumption are highlighted by the work of the Pain and Policy Studies Group (PPSG) at the University of Wisconsin. The PPSG collates national opioid usage data as reported to the International Narcotics Control Board. Fig 1, Fig 2, available from the PPSG website (www.painpolicy.wisc.edu), show opioid consumption data for 2015. Figure 1 shows large disparities in total opioid consumption between geographical regions. Figure 2 shows massive disparities between a selection of countries (e.g. Canada had a total opioid consumption of 853 mg per person in 2015, whereas the consumption in Nigeria was 0.02 mg per person).

Fig 1.

Total opioid consumption by region, 2015. Notes: Opioid consumption is reported as the morphine equivalence amount (mg per capita). Total opioid consumption refers to the combined consumption of morphine, pethidine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone, and hydromorphone.

Fig 2.

Total opioid consumption in a selection of countries, 2015. Notes: Opioid consumption is reported as the morphine equivalence amount (mg per capita). Total opioid consumption refers to the combined consumption of morphine, pethidine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone, and hydromorphone.

There are multiple barriers relating to accessing morphine and other opioids. In many LMICs, systems for procurement and distribution are not robust, and national policies aimed at preventing diversion and misuse also severely limit therapeutic use. In some LMICs, the cost of opioids is significantly higher than in HICs.18

Specific, essential formulations of opioids may not be available (e.g. oral morphine solution or fast-release tablets).19 This severely limits treatment options in the management of postoperative and trauma pain, pain in paediatric patients, and the longer-term treatment of cancer and other terminal diseases.

There are powerful myths related to morphine and other opioids—often related to a lack of pain management education. ‘Opiophobia’ refers to exaggerated concerns (held by healthcare workers, patients, or both) about the adverse effects of opioids and the potential for addiction even in the acute and palliative care settings.20 Alongside this, there is increasing recognition of the limited evidence of efficacy, and the risk of harm of long-term opioid use in CNCP. The current opioid crisis in North America feeds concerns about opioid adverse effects but is attributed by some to overzealous prescribing in CNCP.21 The crisis has led to calls within the USA for doctors to stop describing pain as the fifth vital sign.

Other barriers

The lack of data and research from LMICs, especially in the areas of acute pain and CNCP, poses an important barrier to improving pain management in these countries. Research and measurement can help to drive change and support advocacy, and the converse is true when research is absent.

There can be considerable direct and indirect costs for patients seeking pain treatment. Direct costs include hospital and medical fees; indirect costs may include transportation costs and loss of income. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery highlights the direct and indirect costs of surgical care and the resulting catastrophic expenditure.7

Pain management, especially for CNCP, can be very complex and challenging, even in a highly resourced environment. Traditional medical management may have limited long-term benefits. Balanced against this, there are many opportunities for improved pain management, particularly in acute and end-of-life care in LMICs, using simple cheap treatments.

Solutions

Broadly, strategies for improving pain management in LMICs fit into three areas: advocacy, improving treatment availability, and education. These areas are interdependent.

Advocacy

The impact of inadequately treated pain is increasingly being recognised by the WHO and governments around the world.9, 22 The psychological, social, and economic consequences of pain of all types—cancer and other end-of-life pain, acute pain, and CNCP—need to be highlighted at multiple levels—global, national, and local. Along with an improved awareness of the global burden of pain, there needs to be an understanding that particular types of pain, namely acute pain and pain at the end of life, can be treated with cost-effective and relatively simple treatments.

Increasingly, treatment of pain is being seen in the context of Universal Health Coverage, defined by the WHO as ‘ensuring that all people have access to needed promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health services, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that people do not suffer financial hardship when paying for these services’ (www.who.int/healthsystems/universal_health_coverage/en/). The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3) calls on member states to ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ (www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/). Unfortunately, pain management is not specifically mentioned in the SDG targets; however, adequate palliative care and pain management, including access to appropriate medications and other therapies, are a prerequisite for achieving health for all.

World Health Assembly (WHA) Resolution 68.15 on strengthening surgical services and anaesthesia specifically mentions the need to improve pain relief and access to opioids and other analgesics.9 WHA Resolution 67.19 entitled ‘Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course’ calls on member states to improve palliative care and pain relief.22

At a national and local level, we need to work collaboratively to develop the specialties of pain medicine and palliative medicine. Organisations such as the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA) are working with national professional societies to develop local expertise and leadership.

Currently, there are limited data on the prevalence and impact of cancer pain, acute pain, and CNCP in LMICs. As part of creating awareness and advocacy, high priority should be given to monitoring the impact of interventions to improve pain management. The WHO, for example, currently monitors morphine use as a surrogate marker of palliative care provision, but there is a need to develop and monitor more specific indicators.

Improving treatment availability

Simple treatments can make a big difference but even these may not be available. The LCPCPR suggests an Essential Package of palliative care and pain relief interventions that aims to ameliorate a large part of the preventable burden of SHS.5 The estimated cost of this package per person per year is only US$2.16. The Commission emphatically recommends that oral and injectable morphine are available and part of this package.

The need to modify national level policy in order to ensure opioids are available and accessible has been highlighted by many organisations and initiatives. For example, the WHO's Access to Controlled Medications Programme (ACMP) gives legislative guidance and provides training and practical assistance to governments and healthcare workers.23, 24 The PPSG (www.painpolicy.wisc.edu) collates opioid consumption data, provides a range of resources, and runs projects to reduce regulatory barriers. Many countries around the world have achieved a reasonable balance between legal controls to prevent misuse and diversion, and accessibility for medical use.25 Increased access, however, must be accompanied by policies and education to ensure that healthcare workers prescribe opioid analgesics appropriately when managing different types of pain.

It is also important to not focus solely on improving the availability and use of opioid analgesics. There need to be parallel efforts to improve access to other pharmacological treatments (e.g. medications for treating neuropathic pain) and non-pharmacological treatments (e.g. psychological treatments and management by an MDT).26 These treatment modalities assume greater importance in the management of CNCP and end-of-life pain.

Appropriate access to strong opioid medications and other analgesic treatments not only depends on legal and policy considerations, but also on the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare workers, hence the vital role of education in improving pain management.

Education

Effective pain management education underpins advocacy efforts, and improved availability and use of analgesic treatments. Educational programmes are required to improve knowledge and change attitudes to pain management. Key topics of education include: the benefits of treating pain, non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment options, the concept of multimodal analgesia and multidisciplinary treatment teams, and an understanding of common misunderstandings and myths. Education on the effectiveness and appropriate use of morphine, including correction of misconceptions about adverse effects and addiction, is particularly important.

Patient knowledge and healthcare worker knowledge are linked. Frequently, patients become fatalistic about pain management because of a perception that pain management will not be given a high priority by healthcare workers. A number of free resources are available for healthcare workers in LMICs. These include the IASP's Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists' Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, and the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance's (WHPCA) Palliative Care Toolkit.27, 28, 29 Teaching materials can be found on the IASP, WFSA, and WHPCA websites.

In order to develop pain management services locally, local expertise and leadership is required. The WFSA and IASP offer short-term subspecialty training for clinicians wishing to specialise in pain management. One example is the Bangkok Clinical Pain Management Fellowship—a collaboration between the WFSA, IASP, and Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. This programme was started in 2006 and has trained 18 fellows from nine Asian countries. As with other short-term fellowship programmes, the aim is to create a snowball effect where one specialist will train many more healthcare workers in their home setting.

The Essential Pain Management (EPM) course is a simple 1-day workshop aimed at teaching a multidisciplinary group to better recognise, assess and treat (RAT) pain of all types (www.essentialpainmanagement.org). This course was initially developed for doctors and nurses in LMICs and was first trialled in Papua New Guinea in 2010. Since then, it has been translated into seven languages and taught in over 50 countries worldwide, including a number of HICs. The EPM programme is presented as an ‘off-the-shelf’ package, and includes an instructor workshop, allowing early handover to and ownership by local clinicians. A stated aim of EPM is to change the culture and attitudes related to managing pain of all types. A shorter version of the course has now been used in 18 medical schools in the UK. The LCPCPR recommends that training in pain treatment and palliative care be a mandatory part of all curricula for healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

Cancer pain, acute pain, and CNCP all contribute to a large burden of pain in LMICs, which is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated. Barriers to pain management are considerable, and include poor knowledge and attitudes about pain management, low prioritisation of pain management by governments and hospitals, inappropriate legislation, and limited or non-existent availability of pain treatments. Education will play a central role in overcoming these barriers.

There is increasing recognition by the WHO, governments, and clinicians that pain management and palliative care need to improve in order to achieve Universal Health Coverage. We need to work together to increase awareness, improve knowledge and attitudes, and make appropriate treatments available to achieve the best possible health for all.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Wayne Morriss MBChB DipObst FANZCA is a consultant anaesthetist and clinical senior lecturer at Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand. He is a member of the board and council of the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists and the current Director of Programmes. He is a past chair of the Education Committee of the WFSA and is the coauthor of the Essential Pain Management course.

Clare Roques MSc MA FRCA FFPMRCA is a consultant in anaesthesia and inpatient pain management at Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust. She is the chair and founder member of the Essential Pain Management Advisory Group at the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, a member of the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists' Pain Management Committee, and the past chair and founder member of the Pain in Developing Countries Special Interest Group of the British Pain Society.

Matrix codes: 1D02, 2E03, 3E00

References

- 1.Bond M. Pain education issues in developing countries and responses to them by the International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:404–406. doi: 10.1155/2011/654746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seya M.J., Gelders S.F.A.M., Achara O.U., Milani B., Scholten W.K. A first comparison between the consumption of and the need for opioid analgesics at country, regional, and global levels. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25:6–18. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2010.536307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzmaurice C., Allen C., Barber R. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor S.R., Sepulveda Bermedo M.C. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knaul F.M., Farmer P.E., Krakauer E.L. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2017;6736:1–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker R., Stein D.J., Jelsma J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18719. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meara J.G., Leather A.J.M., Hagander L. The Lancet Commissions Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015;386:569–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faponle A., Soyannwo O., Ajayi I. Post operative pain therapy: a survey of prescribing patterns and adequacy of analgesia in Ibadan, Nigeria. Cent Afr J Med. 2001;47:70–74. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v47i3.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO . 2015. WHA Resolution 68.15. Strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walters J.L., Jackson T., Byrne D., McQueen K. Postsurgical pain in low- and middle-income countries. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:153–155. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayan R. Managing acute pain in the developing world. Why focus on acute pain? IASP Pain Clin Updat. 2011:1–7. XIX. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Telfer P., Bahal N., Lo A., Challands J. Management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease—a re-evaluation of the use of opioids in adult patients. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:157–164. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson T., Thomas S., Stabile V., Shotwell M., Han X., McQueen K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the global burden of chronic pain without clear etiology in low- and middle-income countries: trends in heterogeneous data and a proposal for new assessment methods. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:739–748. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pramesh C.S., Badwe R.A., Borthakur B.B. Delivery of affordable and equitable cancer care in India. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e223–e233. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olayemi O., Morhason-Bello I., Adedokun B., Ojengbede O. The role of ethnicity on pain perception in labor among parturients at the University College Hospital Ibadan. J Obs Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:277–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs E.V., Battelli D., Gordon D. Current pain education within undergraduate medical studies across Europe: advancing the Provision of Pain Education and Learning (APPEAL) study. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006984. e006984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization WHO model lists of essential medicines. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/

- 18.De Lima L., Sweeney C., Palmer J., Bruera E. Potent analgesics are more expensive for patients in developing countries: a comparative study. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleary J., Powell R., Munene G. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Africa: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) Ann Oncol. 2013;24 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt499. xi14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan F., Carr D.B., Cousins M. Pain management: a fundamental human right. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:205–221. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268145.52345.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer B., Keates A., Bühringer G., Reimer J., Rehm J. Non-medical use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid-related harms: why so markedly higher in North America compared to the rest of the world? Addiction. 2014;109:177–181. doi: 10.1111/add.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Assembly WHA67.19 strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf%5Cnhttp://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf.

- 23.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2007 (April). Access to controlled medications programme.http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s14860e/s14860e.pdf 46. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . 2011. Ensuring balance in national policies on controlled substances: guidance for availability and accessibility of controlled medicines.http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/GLs_Ens_Balance_NOCP_Col_EN_sanend.pdf 88. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisberg D., Stannard C. Lost in translation? Learning from the opioid epidemic in the USA. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1215–1219. doi: 10.1111/anae.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamerman P.R., Wadley A.L., Davis K.D. World Health Organization essential medicines lists: where are the drugs to treat neuropathic pain? Pain. 2015;156:793–797. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460356.94374.a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopf A., Patel N.B. 2010. Guide to pain management in low-resource settings. Available at: http://ebooks.iasp-pain.org/guide_to_pain_management_in_low_resource_settings. [Accessed 18 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schug S.A., Palmer G.M., Scott D.A., Halliwell R., Trinca J. ANZCA and FPM; 2015. Acute pain management: scientific evidence. Available from: http://fpm.anzca.edu.au/documents/apmse4_2015_final. [Accessed 25 January 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bond C., Lavy V., Wooldridge R. 2008. Palliative care toolkit—improving care from the roots up. UK: Help the Hospices. [Google Scholar]