Learning objectives.

After reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Summarise the steps in preoperative assessment specific to the patient requiring pneumonectomy.

-

•

Outline the challenges caused by changes in pathophysiology associated with pneumonectomy.

-

•

Describe the approach to anaesthetising a patient for pneumonectomy.

-

•

Identify the common complications after pneumonectomy.

Key points.

-

•

Pneumonectomy has the highest postoperative mortality of all pulmonary resections and should only be considered once all other surgical options have been excluded.

-

•

Complications arise as a result of shunting of the entire pulmonary circulation through a single lung and from the compromise to gas exchange after resection.

-

•

Preoperative assessment should focus on exercise tolerance, physiological reserve, and predicted postoperative respiratory function.

-

•

I.V. fluids should be restricted to help prevent post-pneumonectomy pulmonary oedema in the remaining lung.

-

•

Postoperative cardiac complications are common; up to 40% of patients develop new onset atrial fibrillation.

Pneumonectomy involves the surgical removal of an entire lung. This article aims to cover the perioperative management of a patient undergoing pneumonectomy, including guidance for predicting postoperative risk, up-to-date cancer staging, essential considerations for anaesthesia, surgical approach, and the implications and management of postoperative complications.

History

In 1933, Dr James Gilmore, an obstetrician and gynaecologist, presented to Evarts A. Graham at Barnes Hospital in St Louis, MO, USA for a lobectomy for lung cancer. The findings during the surgery of extension of the cancer resulted in the first successful one-stage pneumonectomy. Gilmore continued to practice medicine for 24 yrs after his surgery.1

Morbidity and mortality

Pneumonectomy comprised 5% of surgeries for lung cancer in England in 2015. The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-yr survival rates were 92.3%, 88.4%, and 74.6%, respectively. This compares to 30-day, 90-day, and 1-yr survival rates of 98.5%, 96.8%, and 89% respectively for bilobectomy, lobectomy and sleeve resection procedures combined.2 Postoperative mortality is strongly linked with increasing age, thought to result partly from the inability of the right ventricle in an older person to tolerate the increase in pulmonary vascular resistance after resection.3 Right pneumonectomy is associated with higher mortality than left, probably because the diversion of cardiac output through the smaller left lung results in increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular failure. There is also a higher incidence of bronchopleural fistula (BPF) with right pneumonectomy. Quality of life after pneumonectomy is poorer compared with after lobectomy or bilobectomy.4

For these reasons, thoracic surgical teams should contemplate pneumonectomy as a last resort. It should only be considered if all other options, including sleeve lobectomy and non-anatomical resections, have been deemed inappropriate, and take into account the assessment of the patient's physiological reserve, including the predicted postoperative (ppo) respiratory function. Conversely, the patient must be fully counselled when an alternative approach to pneumonectomy is possible, but which is associated with a higher risk of cancer recurrence.4

Indications

The most common indication for pneumonectomy is bronchial carcinoma, where the anatomical location is not amenable to alternative resection.5 This includes tumours originating from the main stem bronchus, proximal to the bronchus intermedius, or those with hilar involvement (Fig. 1). Indications in non-malignant disease include traumatic injury to the lung with uncontrolled haemorrhage, chronic infective disorders of the lung (such as tuberculosis), and fungal infections resulting in lung destruction.6

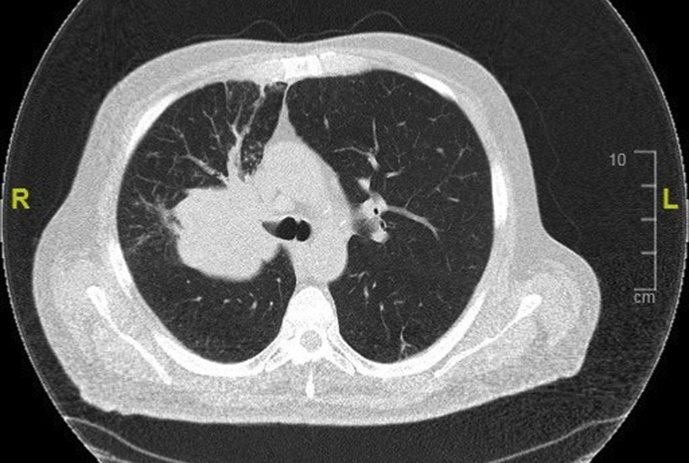

Fig 1.

CT thorax showing a large hilar mass involving the right main bronchus. The most appropriate surgical intervention for this tumour would be right pneumonectomy.

Types of pneumonectomy

There are a variety of approaches to this procedure.7 Standard pneumonectomy is the most common and involves removal of the affected lung only. There must be a safe bronchial margin that allows stapling and closure of the bronchial stump. The pulmonary artery and veins are isolated and ligated without the need for intra-pericardial access.

There are certain scenarios that mandate intrapericardial pneumonectomy, such as when the right or left main pulmonary artery is involved or when there is tumour so close to the pulmonary vein that it has to be isolated and divided at the level of the left atrium to secure a clear vascular margin. Good communication between the surgeon and the anaesthetist is needed, especially when clamping the right or left main pulmonary artery, to enable steps that can be taken to maintain a stable cardiac output.

Extrapleural pneumonectomy is a radical type of resection sometimes performed for selected cases of mesothelioma. This encompasses excision of the affected lung, ipsilateral pleura, hemidiaphragm, and hemipericardium, with patch reconstruction, but it is seldom performed in the UK after the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery trial showed that mortality is worse compared with medical management. Completion pneumonectomy refers to the excision of the residual lung tissue after resection during previous surgery. Carinal pneumonectomy is also rarely carried out; it refers to the excision of the lung and carina in patients with tumours of the distal trachea or carina.8 This article will focus on standard pneumonectomy.

Preoperative assessment

Lung cancer staging

Primary lung cancers can be divided into non-small-cell (NSCLC) and small-cell cancers. NSCLCs count for approximately 85% of cases, and can be subdivided into adenocarcinoma, squamous, and large-cell carcinoma.

Patients with lung cancer should be assessed for staging as per the eighth edition of the tumour, node, metastasis classification (Table 1).9 All should have CT, followed by positron emission tomography CT (PETCT) to assess the lymph node status. If PETCT-positive mediastinal lymph nodes are detected, further mediastinal sampling via an endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy is needed. Radical surgical management should be offered to those with T1-3 N0-1 M0 disease, although those with T4 and N2 disease may still be candidates for surgery depending on discussions within the multidisciplinary team; a radical multimodal treatment may be considered in individual cases.4

Table 1.

Eighth edition lung cancer tumour, node, metastasis staging summary.9

|

T: tumour | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumour <3 cm in greatest dimension, surrounded by lung or visceral pleura, without bronchoscopic evidence of invasion more proximal than the lobar bronchus (i.e. not in the main bronchus) |

| T1mi | Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma |

| T1a | Tumour <1 cm in greatest dimension |

| T1b | Tumour >1 cm, but <2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T1c | Tumour >2 cm, but <3 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumour >3 cm, but <5 cm or tumour with any of the following features:

|

| T2a | Tumour >3 cm, but <4 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2b | Tumour >4 cm, but <5 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumour more than 5 cm, but not more than 7 cm in greatest dimension or one that directly invades any of the following: chest wall (including superior sulcus tumours), phrenic nerve, parietal pericardium; or associated separate tumour nodule(s) in the same lobe as the primary |

| T4 |

Tumours more than 7 cm or one that invades any of the following: diaphragm, mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, oesophagus, vertebral body, carina; separate tumour nodule(s) in a different ipsilateral lobe to that of the primary |

|

N: nodes | |

| N0 | No regional lymph-node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in ipsilateral peribronchial or ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes and intrapulmonary nodes, including involvement by direct extension |

| N2 | Metastasis in ipsilateral mediastinal or sub-carinal lymph node(s) |

| N3 |

Metastasis in contralateral mediastinal, contralateral hilar, ipsilateral or contralateral scalene, or supraclavicular lymph node(s) |

|

M: metastases | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| M1a | Separate tumour nodule(s) in a contralateral lobe; tumour with pleural nodules or malignant pleural/pericardial effusion |

| M1b | Single extra-thoracic metastasis in a single organ |

| M1c | Multiple extra-thoracic metastases in one or several organs |

Suitability for surgery

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) recommends that the preoperative risk assessment for all lung resections be split into three domains.4 These are (i) operative mortality, (ii) perioperative myocardial events, and (iii) postoperative dyspnoea.

Operative mortality

The BTS guidelines advise considering the use of the Thoracoscore to estimate the postoperative mortality for patients undergoing thoracic surgery. This incorporates nine factors: age, sex, ASA score, performance status, dyspnoea score, priority of surgery, extent of surgery, a diagnosis of malignancy, and co-morbidity score.10 However, several studies have shown that the Thoracoscore and other risk models are not accurate in predicting mortality in thoracic surgery.11 Consequently, preoperative assessment should be focused more on the patient's exercise capacity and physiological reserve.

Perioperative myocardial events

An opinion from a cardiologist should be sought for all patients with an active cardiac condition (e.g. unstable angina, heart failure, significant arrhythmias, severe heart valve disease) for optimisation of medical treatment. Patients without an active cardiac condition should be assessed using the Revised Cardiac Risk Index, with those scoring ≥3, or with poor functional capacity, being referred for exercise stress testing and a cardiologist's opinion.4

All patients considered for pneumonectomy should undergo transthoracic echocardiography. This also applies to patients who have unexplained dyspnoea or an audible heart murmur.4 The presence of pulmonary hypertension is a relative contraindication especially for right pneumonectomy because of the inevitable increase in pulmonary vascular resistance after surgery.6

Postoperative dyspnoea

Evaluation of lung function is a fundamental aspect of preoperative assessment for all patients planned for pulmonary resection, and has historically been used as a predictor for postoperative mortality and dyspnoea. Respiratory assessment can be considered under the heading ‘respiratory mechanics’ and ‘lung parenchymal function’.3

Respiratory mechanics: ppo forced expiratory volume in 1 s

This estimates the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) after lung resection, and can be calculated through lung segment counting.4 There are 10 segments on the right and 9 on the left. For patients undergoing lung resection, the following formulae can be applied:

For patients who are being considered for pneumonectomy, ppoFEV1 can also be estimated through perfusion scintigraphy if this study was deemed necessary in those with borderline lung function tests. This test details the proportion of total perfusion to each lung. This information can then be applied to the following formula:

Scintigraphy is of most use in those instances where it identifies that no further lung function would be lost through surgery (e.g. where there is tumour compression of the pulmonary artery, or when the affected lobe is obstructed and not contributing to ventilation), and in those patients where prior assessment has highlighted that such loss would be unacceptable.4

When interpreting these results, the underlying cause for abnormal preoperative FEV1 must be taken into account. A reduced FEV1 may be secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or underlying respiratory muscle weakness, both of which could result in different outcomes from surgery. A lesion obstructing a bronchial lumen is likely to impair baseline test results, but these could be expected to improve after surgery.12

Lung parenchymal function

The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (Dlco) is a measure of the total effective surface area of the alveolar-capillary unit or effectiveness of gas transfer. It is quantified in units of mmol min−1 kPa−1 and also as a percentage predicted according to the patient's characteristics, such as age, sex, ethnicity, and height. The ppo Dlco can be calculated using the equivalent formula for ppo FEV1. FEV1 and Dlco measure different characteristics of respiratory function; hence, a satisfactory result for one may not be reflected in the other. Dlco is now regarded as an important predictor for postoperative morbidity despite normal spirometry, and therefore, is viewed as an essential test for all patients undergoing lung resection.4

Interpretation of ppo FEV1 and Dlco

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines suggest that the recommended limit of ppo values for FEV1 and Dlco for surgical resection is 30%. Those patients with ppo values <30% of predicted for either or both FEV1 and Dlco should be fully aware of the potentially increased risks of postoperative dyspnoea and of needing postoperative long-term oxygen therapy.13 They should also be referred for formal exercise testing.4

Functional assessment of cardiopulmonary interaction

Shuttle walk test

The patients walk between two cones spaced 10 m apart at increasing pace. The test ends when the patient is too breathless to continue. A distance greater than 400 m correlates with peak oxygen consumption greater than 15 ml O2 kg−1 min−1.14 Patients unable to walk more than 400 m should be referred for formal cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

The most valuable measurement from CPET is peak oxygen consumption ( peak). peak of >15 ml O2 kg−1 min−1 is defined as good physiological function.13 Patients with values >20 ml O2 kg−1 min−1 can be considered safe to undergo pneumonectomy, whereas values <10 ml O2 kg−1 min−1 are usually regarded as a contraindication.12 However, there is limited evidence for the use of CPET in categorising those patients who are at high risk of unacceptable postoperative dyspnoea.4

Despite the multitude of investigations available, there is no single test to determine the suitability for pneumonectomy. Preoperative assessment should follow a multidisciplinary patient-centred approach.

Perioperative management for pneumonectomy

Surgical approach

Preoperative rigid bronchoscopy is performed after induction of anaesthesia to confirm there is sufficient length of bronchus free of tumour to proceed. For all cancers involving the bronchus, sleeve lobectomy must be first eliminated as a surgical option. Sleeve lobectomy involves the excision of the affected portion of bronchus and lobe, with anastomosis of the bronchus to the remaining lung. Likewise, if the pulmonary artery is involved in a localised area, the surgeon could attempt to do a vascular sleeve resection, which would involve clamping the artery proximal and distal to the tumour, resecting the involved part of the artery, and re-anastomosis.

The most common surgical approach is via posterolateral thoracotomy at the fifth intercostal space. Excision of the fifth rib may be necessary to achieve adequate surgical exposure. Alternatively, access may be achieved via a video-assisted thoracoscopic approach. The chest should be explored to rule out pleural effusions and metastatic deposits on the pleura or diaphragm.7

If surgery is to continue, the lung is then retracted to expose the anterior hilum. The superior and inferior pulmonary veins and pulmonary artery are then sequentially ligated and divided. After this stage, the bronchus is the only structure connecting the lung to the patient. The bronchus is then stapled and cut, taking meticulous care to ensure no part of the double lumen tube (DLT) or suction catheters are included within the staple line. Bronchial stump patency is confirmed by filling the thorax with warm saline and performing a leak test by applying positive pressure via the tracheal lumen. No bubbling into the saline-filled hemithorax should be visible. A thoracostomy tube is placed basally in the post-pneumonectomy space before closure of the chest7.

Anaesthesia

Induction

The availability of a level 2 bed for postoperative care should be confirmed and two units of red blood cells crossmatched. Postoperative analgesia can be provided by either mid-thoracic epidural analgesia or alternatively via a paravertebral catheter placed by the surgeon. Invasive arterial pressure monitoring and central venous catheterisation are recommended, as vasopressors may be required in order to maintain arterial pressure without infusion of excessive volumes of i.v. fluids, and to compensate for the autonomic effects of neuraxial blockade. A temperature probe and urinary catheter are mandatory. Antibiotics are given according to local guidelines. Anaesthesia may be maintained using a volatile agent or total intravenous anaesthesia. However, the latter is useful in the context of rigid bronchoscopy, where reliable delivery of anaesthetic vapour may not be possible.

Position

The patient is placed in the left or right decubitus position with a table break. Fastidious checking of eye protection, pressure points, and neck position is essential. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is provided by graduated compression stockings. Normothermia should be maintained using a forced air warming blanket and fluid warmer.

Lung isolation

Surgical access necessitates collapse of the operative lung. This is most commonly achieved using a DLT, although, alternatively, a bronchial blocker may be used where it is not possible to place a DLT (e.g. in the presence of a ‘difficult’ airway). All methods require fibreoptic bronchoscopy to confirm appropriate positioning. Left pneumonectomy requires a right-sided DLT to ensure there is no interference with the surgical site. Placement of a right-sided DLT requires scrupulous assessment using fibreoptic bronchoscopy to ensure the correct alignment of the right upper lobe and Murphy's eye of the right lumen, to avoid obstruction of the right upper lobe. We recommend a repeat fibreoptic check after lateral positioning, as this can lead to movement of the DLT. Further checking of the DLT position may be required during the procedure. If a bronchial blocker is used, it must be withdrawn from the bronchus before stapling.

One-lung ventilation (OLV) should be initiated before thoracotomy. Lung-protective ventilatory strategies during OLV are now the accepted standard, and may be achieved with pressure or volume control. There is currently no evidence to favour one mode over the other, and no guidelines outlining the ideal ventilatory targets for OLV. Low-tidal-volume (i.e. <6 ml kg−1) strategies are associated with a lower risk of postoperative respiratory failure compared to higher volumes (8 ml kg−1), the mechanism of which is thought to be the activation of the inflammatory response cascade within the alveoli.3 Recent evidence suggests that low tidal volumes should be implemented with sufficient PEEP. Low tidal volumes in the absence of sufficient PEEP are likely to be harmful.15

The following are the suggested targets during OLV:3

-

(i)

Tidal volume: 5–6 ml kg−1 (ideal body weight)

-

(ii)

Peak airway pressure: <35 cmH20

-

(iii)

Plateau airway pressure: <25 cmH20

-

(iv)

Aiming for normal Paco2

-

(v)

PEEP: 5cm H2O

-

(vi)

Avoid hyperoxia, titrating Fio2 to maintain oxygen saturations of 94–98%.

Haemodynamic management

The haemodynamics of a patient undergoing pneumonectomy are made complex because of the clamping of the pulmonary artery, causing the entire pulmonary circulating volume to be diverted through the remaining lung. Hence, the volume of i.v. fluids should be restricted, whilst avoiding hypovolaemia and acute kidney injury. Ideally, positive fluid balance within the first 24 h should not exceed 20 ml kg−1, and urine output of 0.5 ml kg−1 h−1 should be accepted. There should be no supplementation for ‘third space’ losses.3 Excessive intraoperative and postoperative fluid administrations are associated with a greater risk of post-pneumonectomy pulmonary oedema and respiratory failure, the mortality of which can be up to 50%. I.V. fluids should be restricted to the previous hour's urine output plus 20 ml h−1 within the immediate postoperative period. Haemorrhage must be excluded in the event of hypotension. Hypotension secondary to epidural infusion should be treated appropriately with vasoactive drugs as opposed to i.v. fluids. Invasive cardiac output monitoring has not been validated in patients having thoracotomy because of the presence of an open thorax.

Clamping of the pulmonary artery

The final test for suitability for pneumonectomy is the response to clamping of the ipsilateral pulmonary artery, resulting in the shunting of the pulmonary blood supply into the non-operative lung. Significant cardiovascular collapse or excessive rise in the central venous pressure indicates insufficient compliance of the right ventricle pointing to a very high likelihood of postoperative cardiac complications, which are associated with a high mortality. If physiological deterioration occurs on repeat testing and all other causes of cardiovascular instability are eliminated (including inadvertent surgical compression of the heart), then the surgical and anaesthetic team should decide whether continuation of surgery is appropriate.7 This is rare if appropriate preoperative assessment has been performed.

Postoperative care

After surgery, the patient's trachea should be extubated, ensuring the patient is awake, warm, and comfortable. The patient is transferred to an appropriate postoperative care unit for ongoing management. The aim is to provide patients with adequate analgesia allowing them to cough effectively and clear secretions, and to provide any organ support required. Invasive monitoring of arterial pressure allows titration of vasoconstrictor drugs to provide an adequate MAP, offsetting any vasodilatory effects of the sympathetic blockade associated with epidural or paravertebral analgesia. Close monitoring allows for earlier recognition and treatment of immediate postoperative complications, including haemorrhage, post-pneumonectomy pulmonary oedema, retained secretions, and airway plugging within the contralateral lung and cardiac arrhythmias.

Uncomplicated recovery usually results in patients stepping down to a thoracic surgical ward on day 2 and eventual discharge from hospital within 7–10 days. Being cared for in a dedicated thoracic ward allows for care to be delivered by a team used to the expected recovery and potential complications, such as bronchial toilet, management of chest drains, and epidural/paravertebral analgesia. Interaction with respiratory physiotherapists and the use of respiratory adjuncts, including incentive spirometry devices, can be helpful additions in the postoperative period for those at higher risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.16

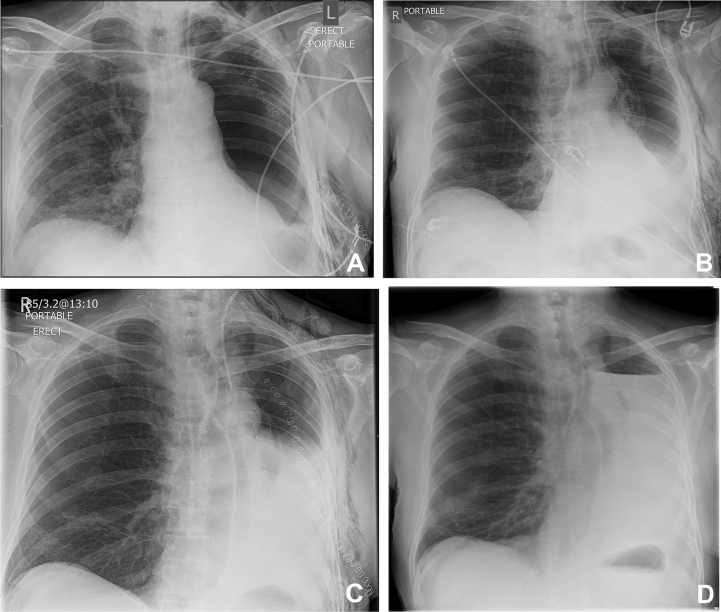

The drain is initially clamped at the end of the surgery and the clamp removed for 1 min every hour to assess for haemorrhage. If the drain is unclamped for prolonged periods of time, there is a risk of acute mediastinal shift into the empty hemithorax and its associated complications, including severe cardiovascular instability. The chest drain is usually removed on the first postoperative day. Subsequently, this allows the operative hemithorax to begin to accumulate serous fluid (Fig. 2). Different practices exist with regard to the use of chest drains, ranging from no chest drain insertion to complex drain management systems to control the pressure within the hemithorax.

Fig 2.

(A) CXR on postoperative day 1 (chest drain removed). (B) CXR on postoperative day 3 showing mediastinal shift and the presence of a fluid collection. (C) CXR on postoperative day 6 showing an increasing accumulation of fluid. (D) CXR on postoperative day 23 showing the presence of a hydrothorax with a clear fluid level.

Postoperative complications

Patients undergoing pneumonectomy are at risk of the more common complications related to pre-existing patient co-morbidities and more specific post-pneumonectomy complications. Below are some of the postoperative complications associated with pneumonectomy surgery; other postoperative pulmonary complications have been well covered in a previous article in BJA Education.17

Cardiac arrhythmias

Cardiac arrhythmias are common after pneumonectomy. It has been reported that up to 40% of patients will develop postoperative atrial fibrillation.18 Other dysrhythmias include atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia. The development of cardiac arrhythmia after surgery is associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased morbidity, and is more likely to occur in elderly male patients with preexisting cardiac disease.19 The management of the arrhythmia involves correction of underlying acid/base and electrolyte abnormalities, and the use of appropriate pharmacological agents. The prophylactic use of beta blockers and amiodarone is currently debated in the literature. Guidelines from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons do not currently recommend the prophylactic use of amiodarone.20 However, guidelines from the American Association for Thoracic Surgery suggest that it is reasonable to administer amiodarone prophylactically after surgery in intermediate-to high-risk patients.21

Post-pneumonectomy pulmonary oedema

Post-pneumonectomy pulmonary oedema occurs in 2–5% of patients with an associated mortality of >50%.22, 23 It is more likely to occur after a right pneumonectomy. Leaky capillary beds within the remaining lung result in patients developing respiratory distress and hypoxaemia, usually within the first 72 h after surgery.

Bronchopleural fistula

A BPF is an abnormal communication between the bronchial tree and pleural space. The incidence after a pneumonectomy ranges from 4.5% to 20% with an associated mortality of 18–67%.24 It is more likely to occur in patients undergoing right pneumonectomy, because the right bronchus is supplied by a single bronchial artery, whereas the left is supplied by two. Furthermore, the right bronchial stump is exposed at the end of the operation; therefore, surgeons aim to cover the stump with a well-vascularised tissue flap, such as the intercostal muscle, to protect the stump. A left stump may be covered too; however, it tends to retract behind the aortopulmonary window and usually becomes covered by the patient's own natural tissues within the mediastinum. Other risk factors for BPF include prolonged postoperative ventilation, residual tumour in stump, and large diameter stumps. Patients with an early BPF present with cough, continued air leak from chest drain, falling fluid level, or new air fluid level on chest radiographs. Later (>2 weeks) BPF presentations can have more non-specific signs and are often associated with an empyema. Management can be very difficult. Treatment is draining the pleural space if it is associated with an empyema, antibiotics, and surgical repair of the fistula.

The patient's condition must be stabilised and optimised medically but on rare occasions surgical repair may be necessary despite the presence of systemic sepsis, hypoxia, and respiratory failure. These patients can be very challenging to anaesthetise, as they can present in a state of cardiovascular collapse, yet require rapid lung isolation to facilitate surgical re-exploration of the hemithorax and avoid overspill from the BPF into the remaining lung.

Cardiac herniation

Cardiac herniation is a rare complication associated with a right-sided pneumonectomy that has required stripping of the pericardial sac or a left intrapericardial pneumonectomy. It is the result of the heart herniating through the pericardial defect into the postpneumonectomy space. Mortality associated with this complication is greater than 50%.25 Patients develop acute hypotension, shock, and cyanosis, with evidence of superior vena cava obstruction, and may complain of chest pain and shortness of breath, which can rapidly progress to cardiac arrest. These patients require immediate surgery to return the heart to its correct position, close the pericardial defect, and prevent recurrence.26

Conclusions

Pneumonectomy should only be performed as a last resort because of the high mortality associated with the procedure. Appropriate preoperative assessment, risk stratification, and counselling about the expected postoperative course are vital. A multidisciplinary approach helps to optimise the patients' care in the postoperative period, allowing for early recognition and treatment of potentially fatal complications.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Mohammad Hawari, who kindly reviewed a draft of this manuscript, for his comments and suggestions.

Biographies

Stephen Hackett FRCA has recently completed a fellowship in thoracic anaesthesia.

Richard Jones FRCA has recently completed a fellowship in thoracic anaesthesia.

Rik Kapila FRCA is a consultant anaesthetist at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. Dr Kapila has specialist interests in thoracic anaesthesia, medical education, and quality improvement.

Matrix codes: 1H02, 2A03, 3A01

References

- 1.Horn L., Johnson D., Evarts A. Graham and the first pneumonectomy for lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3268–3275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians and Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland . November 2017. Lung cancer clinical outcome publication 2017 (for surgical operations performed in 2015)https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/lung-cancer-clinical-outcome-publication-2017-audit-period-2015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slinger P. Update on the anaesthetic management for pneumonectomy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:31–37. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32831a4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim E., Baldwin D., Beckles M. Guidelines on the radical management of patients with lung cancer. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl. III) doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.145938. iii1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James T.W., Faber L.P. Indications for pneumonectomy. Pneumonectomy for malignant disease. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1999;9:291–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson J., Pennefather S., McCahon R., editors. Thoracic Anaesthesia. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. Surgery to the lung and upper airways; pp. 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerfolio R.F., Bryant A.S. Pneumonectomy. In: Kaiser L., Kron I., Spray T., editors. Mastery of Cardiothoracic Surgery. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2014. pp. 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weder W., Inci I. Carinal resection and sleeve pneumonectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(Suppl. XI):S882–S888. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.08.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstraw P., Chansky K., Crowley J. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;11:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcoz P.E., Conti M., Brouchet L. The Thoracic Surgery Scoring System (Thoracoscore): risk model for in-hospital death in 15,183 patients requiring thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley A., Marshall A., Abdelaziz M. Thoracoscore fails to predict complications following elective lung resection. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1496–1501. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunelli A., Kim A., Berger K. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(Suppl. V) doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2395. e166S–90S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . March 2019. Clinical guideline [NG122]. Lung cancer: diagnosis and management.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Win T., Jackson A., Groves A.M. Comparison of shuttle walk with measured peak oxygen consumption in patients with operable lung cancer. Thorax. 2006;61:57–60. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.043547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blank R., Colquhoun D., Durieux M. Management of one-lung ventilation: impact of tidal volume on complications after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:1286–1295. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agostini P., Naidu B., Cieslik H. Effectiveness of incentive spirometry in patients following thoracotomy and lung resection including those at high risk for developing pulmonary complications. Thorax. 2013;68:580–585. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies O., Husain T., Stephens R. Postoperative pulmonary complications following non-cardiothoracic surgery. BJA Educ. 2017;17:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decker K., Jorens P., Schil P. Cardiac complications after noncardiac thoracic surgery: an evidence-based current review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1340–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04824-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roselli E.E., Murthy S.C., Rice T.W. Atrial fibrillation complicating lung cancer resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernando H., Jaklitsch M., Walsh G. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons practice guideline on the prophylaxis and management of atrial fibrillation associated with general thoracic surgery: executive summary. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frendl G., Sodickson A., Chung M. 2014 AATS guidelines for the prevention and management of perioperative atrial fibrillation and flutter for thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:e153–e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slinger P. Post-pneumonectomy pulmonary edema: is anesthesia to blame? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 1999;12:49–54. doi: 10.1097/00001503-199902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulu A., Pastores S.M., Park B., Riedel E., Rusch V., Halpern N.A. Prevalence and mortality of acute lung injury and ARDS after lung resection. Chest. 2006;130:73–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar P., Chandak T., Shah R., Talwar A. Diagnosis and management bronchopleural fistula. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2010;52:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Self R.J., Vaughan R.S. Acute cardiac herniation after radical pleuropneumonectomy. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:564–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu J., Ishida Y., Hirano Y. Cardiac herniation following intrapericardial pneumonectomy with partial pericardiectomy for advanced lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;9:68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]