Key points.

-

•

Eighty per cent of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in paediatrics occurs in those with identifiable risk factors.

-

•

VTE is associated most commonly with central venous catheters.

-

•

Adolescents are at an increased risk of VTE, and this risk should be assessed.

-

•

Prophylaxis can be mechanical and pharmacological. Low-molecular-weight heparin is used for treatment and prophylaxis.

-

•

Neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks can be performed safely if timed correctly around anticoagulant drugs.

Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Explain the risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in children.

-

•

Describe the presentation and investigation of VTE.

-

•

Assess when prophylaxis is required and implement anticoagulation appropriately.

-

•

Identify when it is safe to perform regional anaesthesia.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a condition where a blood clot forms in the deep veins of the arm, groin or leg (deep vein thrombosis [DVT]), which can subsequently travel through the circulation and occlude the pulmonary vasculature (pulmonary embolism [PE]). Cerebral venous thrombosis makes up a small number of VTE in children, but is not covered in this article.

VTE is a recognised cause of morbidity and mortality in the hospitalised adult. It is preventable, and there are national guidelines on recognising risk factors and when to initiate prophylaxis.1 The incidence of VTE in paediatrics is considerably lower than in adults, but it is still identified in the hospitalised child, particularly in tertiary care facilities. Most children diagnosed with VTE have a number of identifiable risk factors.

Epidemiology

The estimated annual incidence of VTE in general paediatrics ranges from 0.14 to 0.21 per 10,000 children.2 In hospitalised children, the incidence of VTE is five to eight cases per 10,000 hospital admissions.3 The actual incidence could be significantly higher as the majority of VTE is asymptomatic. VTE can either be provoked (i.e. resulting from underlying conditions or identifiable risk factors) or unprovoked. In hospitalised children, 80% of VTE is provoked, occurring in patients with more than one risk factor. Only 2–8.5% of VTE occurs in children with no risk factors—most of them occur later in childhood and adolescence. This is in contrast to the hospitalised adult, where up to 50% of VTE occurs in the absence of risk factors.4

There are two peaks in the overall incidence: one in infants less than 2 yrs old and the other in adolescence.4 In adolescents, the risk factors of smoking, obesity, pregnancy and the combined oral contraceptive pill are relevant and need to be incorporated into risk assessments. Adolescent females are twice as likely to develop VTE than males.5

Risk factors

The risk of VTE is much lower in children, and there are several factors that contribute to the lower incidence.

-

(i)

Children are less likely to have acquired risk factors, such as smoking, oral contraception, pregnancy and malignancy.

-

(ii)

Fewer children have diseases that damage the vascular endothelium (e.g. diabetes and hypertension).

-

(iii)

There are significant physiological differences in the coagulation system of a child compared with an adult.

The coagulation cascade, common pathway, and fibrinolytic processes are continually developing from the neonatal period through to adulthood, and these affect the overall function of the pathway.6 The concentrations of vitamin K-dependent coagulation proteins at birth are 50% of adult concentrations, and increase to reach adult concentrations by 6 months of age.7 There are significantly lower levels of seven procoagulants in children (II, V, VII, IX, X, XI, and XII) than in adults.7 The levels of thrombin inhibitor, α2-macroglobulin, are double that found in adults, and children aged 1–6 yrs have a 25% lower ability to form thrombin compared with adults aged 20–25 yrs.7

The risk factors for VTE in children are summarised in Table 1, and can be explained by Virchow's triad of hypocoagulability, stasis, and endothelial injury or dysfunction. More than 80% of VTE occurs in paediatric patients with one or more risk factors; only 5% has no identifiable risk.7, 8

Table 1.

Risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in children. Reproduced with permission from the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Children.8 CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter

| Age | Incidence of VTE highest age <1 or >13 yrs |

| Central venous catheter (CVC) | Present in >90% of neonatal VTE Present in >33% of other cases Highest risk if CVC in lower limb > subclavian > jugular Risk may be higher in PICC lines |

| Surgery | Present in 10–15% of cases |

| Malignancy | Present in 25% of cases Doubles risk of VTE High risk with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

| Infection/sepsis | Present in >33% cases |

| Major trauma/burns | Present in approximately 10% of cases |

| Drugs | Chemotherapy (e.g. asparaginase) Oestrogen contraceptive pill (3-fold increase) Parental nutrition (may be related to presence of CVC) |

| Immobility | Present in 25% of cases of prolonged best rest |

| Pregnancy | 2-fold increase |

| Congenital thrombophilia | Factor V Leiden Antithrombin III deficiency Protein C/S deficiency Increased factor VIII |

| Acquired thrombophilia | Nephrotic syndrome Antiphospholipid syndrome Connective tissue disease |

| Obesity | Increased incidence of VTE |

| Cardiac disease | Congenital heart disease and its surgery |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Ulcerative colitis greater than Crohn's disease |

| Sickle cell disease | |

| Venous anomalies | IVC atresia, May–Thurner syndrome |

The most important risk factor is the presence of a central venous catheter (CVC). Other factors include infection, immobility, trauma, malignancy, chronic inflammatory conditions and inherited thrombophilias.8 Two-thirds of VTE in children is associated with a CVC.8 This relationship explains why the anatomical site of VTE in children occurs with equal incidence in the upper and lower limbs.3 The site of the CVC is important: there is a higher incidence of VTE with lines sited in the femoral (32%), subclavian (27%), and brachial (12%) veins compared with the internal jugular vein (8%). The choice of CVC type and size does not significantly influence the risk.9

Clinical manifestations

The signs and symptoms of VTE vary depending on the location and extension of the thrombus.

Central venous catheter

CVC-related VTE is often asymptomatic, but can present with repeated loss of line patency, catheter-associated sepsis, appearance of contralateral circulation over the chest wall, neck and face swelling, and swelling of the related limb.

Deep vein thrombosis

DVT most commonly presents in the lower limbs, especially in the iliac, femoral and popliteal veins. There is unilateral leg, inguinal and buttock pain, and swelling and discolouration of the associated limb. Calf diameter is increased on the affected side.

Pulmonary embolism

PE in children is rare, but should be considered in any critically ill paediatric patient exhibiting cardiovascular instability. Patients can present with pleuritic chest pain, cough, tachypnoea, hypoxia, tachycardia, and collapse. Evidence of a DVT may also be present.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic approach depends on the location of the suspected thrombus. The British Committee for Standards in Haematology produced guidelines on the investigation and management of venous thrombosis in children.10 This guidance forms the basis of the following sections on diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis of upper-limb VTE

Ultrasound (US) is ‘recommended for the initial assessment of the peripheral upper limb, axillary, subclavian and internal jugular veins’.10 It may be insensitive for the detection of central intrathoracic VTE, and if this is suspected, contrast magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is recommended. Multidetector CT venography can be considered for the assessment of the central veins if MRV is unavailable, but the radiation exposure needs to be considered.

Diagnosis of lower-limb VTE

The guidance states that Doppler US is recommended to assess the lower-limb venous system for VTE. If the clinical suspicion of a DVT remains high, then the US can be repeated after a week to assess for progression of a calf vein thrombosis. MRV should be ‘considered in children with suspected extension of a femoral VTE’.10

Diagnosis of PE

There are no specific studies in paediatrics, so recommendations in the guidance are based on adult studies. CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is recommended as the initial imaging modality for suspected PE. Isotope lung scanning ‘may be considered as the initial imaging investigation’ if there is no significant cardiopulmonary disease and the child has a normal chest X-ray. Non-diagnostic isotope lung scanning ‘should be followed by further imaging. Patients with a negative CTPA do not require further imaging’. Pulmonary magnetic resonance angiography ‘should be considered as an alternative to CTPA when iodinated contrast injection or radiation is a concern’.10

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations help exclude systemic disorders in children presenting with VTE. Haematology investigations (full blood count and clotting screen) and renal function should be performed to confirm safe baselines before the initiation of anticoagulation. D-dimers vary with age, and the results are difficult to interpret so they should not be used to exclude VTE in children.

Taking a detailed family history of VTE is an important step in the diagnosis, but the finding of inherited thrombophilia defects does not change the initial management of a child with a VTE. The presence of specific defects may be associated with a higher risk of recurrent thrombosis. The ‘routine testing for heritable thrombophilia in children presenting with a first episode of VTE is not indicated and the initial treatment should be the same regardless’.10

Treatment

The treatment of VTE in children depends on the type of thrombus. The aim of treatment is to stop progression and embolisation of the thrombus, prevent recurrence, and minimise long-term complications. The duration of treatment depends on whether the VTE was provoked or unprovoked.

Anticoagulant medication should be started with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Unfractionated heparin (UFH) can be used where rapid reversal of anticoagulation may be required (e.g. high risk of bleeding after surgery). LMWH has several advantages over UFH: the response is more predictable, it requires less monitoring and dose adjustment, and can be administered subcutaneously.11

For ongoing therapy in children over 1 yr of age, oral vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), such as warfarin, may be appropriate. However, continuing LMWH is often advantageous for the majority of patients and is recommended in infants under 1 yr of age. VKA control can be particularly difficult in young patients and those taking multiple medications; it also requires frequent venepuncture. Direct oral anticoagulants (e.g. rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran) are used in adults for the treatment of VTE. Clinical trials are underway in paediatrics to determine safety and dosing; they should not be prescribed to children outside the context of a trial.

Paediatric patients with a provoked VTE should receive anticoagulation therapy for 3 months. For children with a CVC-associated VTE, the catheter should be removed 3–5 days after the start of the anticoagulation therapy if feasible. An indwelling CVC can be kept in situ if it is still required and patent. A shorter duration of anticoagulant treatment (e.g. 6 weeks) may be appropriate if the CVC has been removed, the child is asymptomatic, and there is resolution of the thrombus on repeat imaging.11 When a CVC is blocked but no thrombus is identified in the vessel, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase) may be used to lyse the thrombus and restore catheter patency.11

For patients with an unprovoked VTE, anticoagulation therapy should continue for a minimum of 6 months. Children with recurrent unprovoked VTE and children with antiphospholipid syndrome should have lifelong therapy. If systemic anticoagulation is contraindicated in older children with a lower limb VTE, the insertion of a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter should be considered.

For patients with a PE, anticoagulation therapy should be continued for 3–6 months if the PE was provoked, or a minimum of 6 months if unprovoked. An extensive PE causing haemodynamic compromise can be treated with thrombolytic agents. Both urokinase and tPA have been successfully used in children; tPA is preferred in paediatrics because of its low immunogenicity. Treatment plans should be individualised and involve a discussion with a consultant specialising in paediatric haematology, as there is a significant risk of bleeding.11 Table 2 summarises the different therapeutic agents and dosing recommendations for the treatment of VTE in children.

Table 2.

Therapeutic anticoagulant agents and suggested dosing recommendations for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in children10, 11

| UFH | ||||

| <1 yr | >1 yr | |||

| Loading dose | 75 IU kg−1 over 10 min i.v. | |||

| Starting dose | 28 IU kg−1 h−1 i.v. | 18–20 IU kg−1 h−1 i.v. | ||

| Infusion rates adjusted according to APTT result | ||||

| OR infusion rates titrated to achieve Anti-Factor Xa activity 0.35–0.7 IU ml−1 | ||||

| LMWH | ||||

| Enoxaparin | ||||

| <5 kg or <2 months | 5–45 kg or >2 months | >45 kg | ||

| 1.5 mg kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 1 mg kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 2 mg kg−1 every 24 h s.c. | ||

| Dalteparin | ||||

| <5 kg | >5 kg | |||

| 150 IU kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 100 IU kg−1 every 12 h s.c. or 200 IU kg−1 every 24 h s.c. | |||

| Tinzaparin | ||||

| 0–2 months | 2–12 months | 1–5 yrs | 5–10 yrs | 10–16 yrs |

| 275 IU kg−1 s.c. | 250 IU kg−1 s.c. | 240 IU kg−1 s.c. | 200 IU kg−1 s.c. | 175 IU kg−1 s.c. |

| Monitor effect by measuring Anti-Factor Xa activity. Sample should be taken 3–4 h after s.c. injection. Target level: 0.5–1.0 IU ml−1 | ||||

| Warfarin | ||||

| Initial dose: 0.2 mg−1 kg−1 for 2 days. Subsequent dose adjustments based on INR result. Target INR: 2.5 | ||||

| Tissue plasminogen activator | ||||

| For thrombolysis in suspected massive PE | ||||

| Recommendations vary. Alteplase: 0.1–0.5 mg−1 kg−1 h−1 i.v. for 4–6 h. Lower dose: 0.015–0.06 mg−1 kg−1 h−1 i.v. for 12–96 h has been used and may reduce bleeding risk. | ||||

| For treatment of a blocked central venous catheter | ||||

| <10 kg | >10 kg | |||

| Alteplase | Dilute to 0.5 mg ml−1 | Dilute to 1 mg ml−1 | ||

| Volume: to internal volume of catheter lumen Maximum: 1 ml per lumen |

Volume: to internal volume of catheter lumen Maximum: 2 ml per lumen |

|||

| Leave for 2 h, and then attempt to aspirate. If unsuccessful, the process can be repeated once more; if the lumen remains blocked, then an imaging study (US or venography) is recommended. | ||||

Outcome

There is significant morbidity associated with VTE; 6–8% of children will present with a recurrent DVT and 12% will develop post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS).3, 12 Symptoms of PTS include mild oedema and ulceration of the limb with chronic venous insufficiency and chronic pain. Mortality from VTE ranges from 2.2% to 8.4%; the majority of deaths are secondary to PE.3, 13

Prevention

The evidence for the effectiveness of VTE prophylaxis in paediatrics is limited. The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (APAGBI) Guidelines Working Group on thromboprophylaxis in children recently summarised the evidence and formulated a set of guidelines, which form the basis of the following section.8

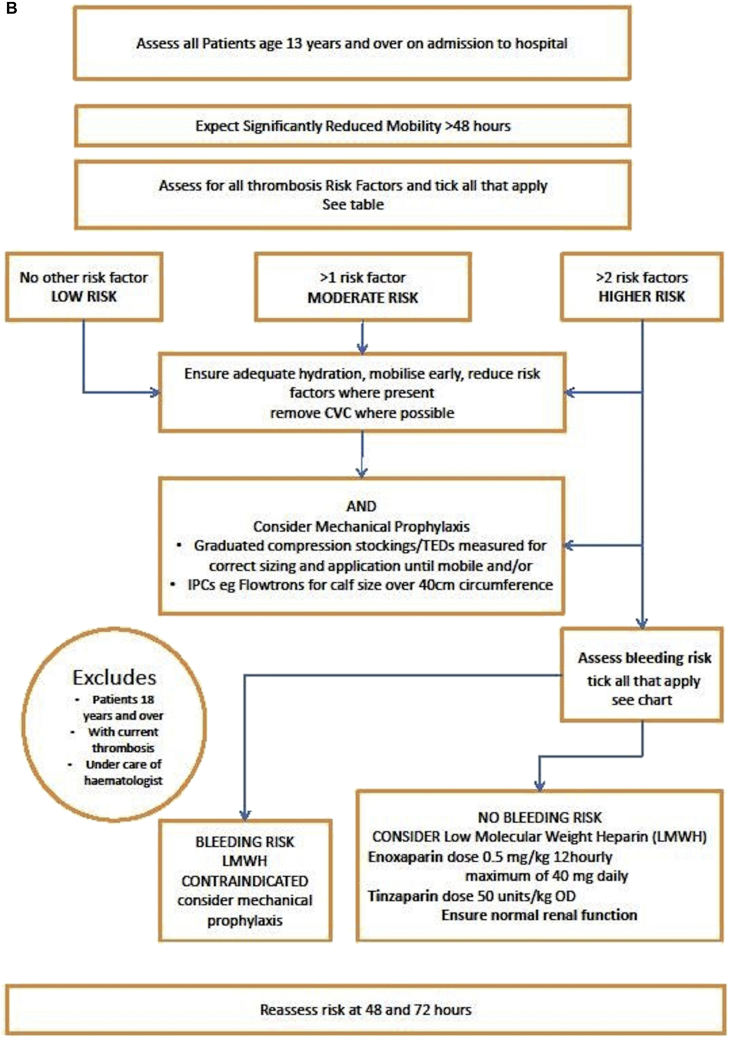

Most paediatric patients do not require thromboprophylaxis, but the risk of developing a VTE should be assessed on admission to a hospital, before operative procedures, and throughout the stay in the hospital. The assessment should focus on adolescents (>13 yrs), particularly those with more than one risk factor or those with anticipated immobility during their hospital stay. The APAGBI Working Group constructed an algorithm and flow chart for assessing VTE risk in patients aged 13 yrs old and over (see Fig. 1A and B).8

Fig 1.

(A) Risk assessment table for VTE for adolescents age 13 yrs and over.8 Reproduced with permission from the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Children. (B) Flow chart for risk assessment for VTE for adolescents age 13 yrs and over.8 Reproduced with permission from the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Children.

Methods of VTE prophylaxis

Immobility and dehydration reduce blood flow through the venous system, and increase blood viscosity. Early mobilisation and hydration should be encouraged in all patients. VTE prophylaxis consists of mechanical and pharmacological methods. If both forms of prophylaxis are used in combination, the risk of VTE is reduced further.

Mechanical methods

Mechanical prophylaxis includes the use of antiembolism stockings and pneumatic compression devices. They reduce lower limb venous stasis and increase blood velocity, but do not increase the risk of bleeding so may be preferred in patients with a bleeding tendency.14 There are no formal studies of mechanical prophylaxis in children, and no paediatric sizes of anti-embolism stocking or intermittent pressure compression boot are available, so their use is limited to larger children and adolescents weighing >40 kg.

Antiembolism stockings

Antiembolism stockings are a static form of mechanical prophylaxis. The exact mechanism of graduated compression stockings is unclear. There is evidence to suggest the circumferential pressure combined with muscular activity displaces blood from the superficial venous system into the deep system, increasing flow, and potentially preventing thrombosis formation.15 They are available in an above- or below-knee design, but there is not enough evidence to determine if one is more effective.16 The above-knee design is more uncomfortable and less likely to be worn correctly.1 There are no paediatric sizes, so they can only be used in children or adolescents >40 kg and should be worn until mobility returns.

Intermittent pressure compression boots

Intermittent pressure compression boots are a dynamic form of mechanical prophylaxis. They wrap around legs and provide pulsatile compression: this promotes fibrinolysis and reduces venous stasis in the deep leg veins. They are recommended for intraoperative use unless contraindicated in adolescents over 13 yrs of age that weigh over 40 kg and are expected to undergo a surgical procedure lasting over 60 min.17

Contraindications to mechanical prophylaxis

Contraindications include the following:

-

(i)

Severe leg oedema or pulmonary oedema secondary to cardiac failure

-

(ii)

Severe peripheral neuropathy or vasculopathy

-

(iii)

Local conditions affecting the skin (dermatitis, recent skin graft, poor tissue viability, and leg wound infection)

-

(iv)

Extreme leg deformity8

-

(v)

Intermittent pressure compression boots should not be used if the patient has a suspected or confirmed DVT or pulmonary embolism.1

Pharmacological prophylaxis

Pharmacological prophylaxis is reserved for children with multiple risk factors for VTE (Fig. 1A and B). LMWH is the preferred choice. Newborn infants require an increased dose, as clearance is age dependent and neonates have accelerated clearance. Twice-daily dosing in children (<5 yrs) is effective and based on half-life and clearance (Table 3). Doses can be administered via a subcutaneous catheter (e.g. Insuflon) to avoid repeated injections. LMWH is excreted via the kidneys, so doses and timings will need to be altered in patients with impaired renal function and should be discussed with a haematology specialist. Monitoring of Anti-Factor Xa may be required to ensure clearance.8

Table 3.

Prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin dosing recommendations for the prevention of VTE in children8, 10

| Prophylactic dosing regimens for LMWH | ||

| Enoxaparin | ||

| <5 kg or <2 months | 5–45 kg or >2 months | >45 kg |

| 0.75 mg kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 0.5 mg kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 40 mg every 24 h s.c. |

| Dalteparin | ||

| <5 kg | >5 kg | |

| 75 IU kg−1 every 12 h s.c. | 50 IU kg−1 every 12 h s.c. or 100 IU kg−1 every 24 h s.c. | |

| Tinzaparin | ||

| Use only if >1 month old; 50 IU kg−1 every 24 h s.c. | ||

| Monitor effect by measuring the Anti-factor Xa activity. | ||

| Sample should be taken 3–4 h post-s.c. injection. | ||

| Target level: 0.1–0.4 IU ml−1 | ||

Adverse effects of pharmacological prophylaxis

There are very few studies looking at the adverse effects of LMWH in paediatric patients. An increase in bleeding is always a concern. In a prospective cohort study of 146 paediatric patients receiving therapeutic LMWH and 31 patients receiving prophylactic LMWH, there were no major bleeds, and only two minor bleeds at the site of the subcutaneous catheter.18 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is also a recognised complication of heparin exposure. HIT affects 5% of adult patients exposed to heparin; the incidence in paediatric patients is up to 2.3%. It is more likely with therapeutic than prophylactic doses of heparin, and the frequency is less if LMWH is used.19, 20 If HIT is suspected, a paediatric haematologist should be consulted. The anticoagulant drugs need to be changed, and options include argatroban, danaparoid, bivalirudin, and fondaparinux.10, 20

Safe practice of regional anaesthesia with anticoagulant prophylaxis

Regional anaesthesia can provide protection from VTE. Its use needs to be weighed up against the risk of vertebral canal haematoma after a spinal or epidural block in a patient receiving anticoagulation. There are no studies examining the frequency and severity of haemorrhage after plexus or peripheral blocks in anticoagulated patients.21

The risk of haematoma is higher when:

-

(i)

There is a complicated puncture.

-

(ii)

Certain neuraxial blocks are used (epidural catheters > single shot epidural > single shot spinal).

-

(iii)

There is concomitant use of LMWH with other anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs.

-

(iv)

There is an insufficient interval between LMWH administration and performance of the block. Dosing schedules should be two times the elimination half-life of the drug to coincide with the lowest blood concentration of the anticoagulant.

-

(v)

There is renal or hepatic impairment that prevent clearance of the LMWH.8

The following are the points to consider:

-

(i)To perform a block or remove a catheter:

-

(a)International normalised ratio=1.5 or lower

-

(b)Functioning platelets >50×109 L−1

-

(c)Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) <45 s8

-

(a)

-

(ii)

For patients on prophylactic LMWH therapy: 12 h interval after standard prophylaxis before a block is performed, and before an epidural catheter is repositioned or removed8

-

(iii)

For patients on therapeutic LMWH therapy: 24 h interval after LMWH before the block is performed, and before an epidural catheter is repositioned or removed19

-

(iv)

For patients receiving an infusion of UFH, stop the infusion 2–4 h before surgery and check that the APTT has normalised. Restarting the infusion after surgery depends on the procedure performed and should be discussed with the surgeon, but should be at least 1 h after performing the neuraxial block.21

-

(v)

If there is blood in the needle or catheter, LMWH should be delayed 24 h and anything that may increase the risk of spinal bleeding (e.g. NSAIDs) should be avoided in the immediate postoperative period.8

-

(vi)

Patients with indwelling catheters should have the first dose of LMWH 12 h after surgery.

-

(vii)

In children receiving once daily or twice daily LMWH, the removal of catheter should be delayed until at least 8 h after the last dose of LMWH.

-

(viii)

The next dose of LMWH should be given at least 4 h after the removal of an epidural catheter.

-

(ix)

Neurological observations should continue for 24 h after removal of a catheter.8

Plexus and peripheral nerve block in the anticoagulated patient

There are no studies examining the frequency or severity of bleeding after plexus or peripheral nerve blocks in anticoagulated patients, and more information is required before recommendations can be made.

There are reports of vascular injury resulting in nerve injury in patients with normal or abnormal haemostasis; in all cases, neurological recovery was complete within 6–12 months. The APAGBI Working Group suggested it might be sensible to apply the same guidelines as for neuraxial blocks regarding the timing of LMWH and performing the regional anaesthetic technique, including the insertion and removal of plexus catheters.8

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Stephanie Jinks FRCA is a locum consultant anaesthetist at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust. She has special interests in medical education and quality improvement.

Amaia Arana FRCA is a consultant paediatric anaesthetist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust with a specialist interest in pain management. She was a member of the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists Guidelines Development Group for the prevention of perioperative venous thromboembolism in children.

Matrix codes: 1A02, 2A03, 3D00

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk for patients in hospital. Guidance and guidelines. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89. Accessed date March 2018

- 2.van Ommen C.H., Heijboer H., Buller H.R. Venous thromboembolism in childhood: a prospective two-year registry in The Netherlands. J Pediatr. 2001;139:676–681. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.118192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrew M., David M., Adams M. Venous thromboembolic complications (VTE) in children: first analyses of the Canadian registry of VTE. Blood. 1994;83:1251–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalmers E.A. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in neonates and children. Thomb Res. 2006;118:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biss T.T., Alikhan R., Payne J. Venous thromboembolism occurring during adolescence. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:427–432. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark D. Venous thromboembolism in paediatric practice. Paediatr Anaesth. 1999;9:475–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1999.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew M., Vegh P., Johnston M., Bowker J., Ofosu F., Mitchell L. Maturation of the hemostatic system during childhood. Blood. 1992;80:1998–2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan J., Checketts M., Arana A. Prevention of perioperative venous thromboembolism in pediatric patients: guidelines from the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28:382–391. doi: 10.1111/pan.13355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Male C., Julian J.A., Massicotte P., Gent M., Mitchell L. Significant association with location of central venous line placement and risk of thrombosis in children. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:516–521. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers E., Ganesen V., Liesner R. Guidelines on the investigation, management and prevention of venous thrombosis in children. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:196–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monagle P., Chan A., Goldenberg N. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children. Chest. 2012;141:e737S–e801S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan A.K., Deveber G., Managle P., Brooker L.A., Massicotte P.M. Venous thrombosis in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1443–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newall F., Wallace T., Crock C. Venous thromboembolic disease: a single-centre case series study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:803–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris R.J., Woodcock J.P. Evidence-based compression: prevention of stasis and deep vein thrombosis. Ann Surg. 2004;239:162–171. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109149.77194.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachdeva A., Dalton M., Amaragiri S.V., Lees T. Elastic compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD00148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001484.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sajid M.S., Tai N.R.M., Goll G., Morris R.W., Baker D.M., Hamilton G. Knee versus thigh length graduated compression stockings for prevention of deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raffini L., Trimarchi T., Beliveau J., Davis D. Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: a patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1326–1332. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dix D., Andrew M., Marzinotto V. The use of low molecular weight heparin in pediatric patients: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr. 2000;136:439–445. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newall F., Barnes C., Ignjatovic V., Monagle P. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:289–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabbous M., Sakr F., Maleeb D. Anticoagulant therapy in pediatrics. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2014;5:27–33. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.134947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies G., Checketts M.R. Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic drugs. CEACCP. 2012;12:11–16. [Google Scholar]