Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Describe the indications for resuscitative thoracotomy.

-

•

Explain how the procedure should be conducted.

-

•

Identify which patients have the best chance of survival.

Key points.

-

•

Resuscitative thoracotomy is increasingly performed in the emergency department for penetrating trauma.

-

•

Clinical urgency may mean that non-surgeons carry out the procedure.

-

•

Anaesthetists have multiple key roles in facilitating resuscitative thoracotomy.

-

•

The type of injury and time to procedure determine the patient's chance of survival.

-

•

The best survival rates are for surgery after a single knife wound to the heart.

What is resuscitative thoracotomy?

Resuscitative thoracotomy (RT) is an immediate thoracotomy carried out on patients who are in a ‘peri-arrest’ state or in established cardiac arrest, usually after trauma. To have a reasonable chance of survival, the procedure must be performed rapidly, and for this reason, it is frequently conducted outside the operating theatre. The lack of immediate availability of surgical expertise may require that the operator is from a non-surgical specialty. Although the procedure is still uncommon in most UK hospitals, an increase in the incidence of penetrating trauma has resulted in the intervention being increasingly performed in emergency departments. When standards were set for the launch of trauma networks in England in 2012, one of the major trauma centre standards was the facility to provide immediate RT in receiving emergency departments.1 All hospitals that receive patients after trauma have to consider the training and preparation required to receive these patients in whom intervention is time critical. This article will not consider emergency thoracotomy after cardiac surgery because, in many respects, it is significantly different to emergency department thoracotomy.

Background

Resuscitative thoracotomy was described in 1874 as a resuscitation manoeuvre for performing open heart massage in cases of cardiopulmonary arrest.2 The first thoracotomy performed to treat a penetrating cardiac injury was described by Ludwig Rehn in 1896.3 The procedure became widespread as an intervention in the emergency department, particularly in the USA after the 1960s. By this time, thoracotomy for medical cardiac arrest had been replaced by closed cardiac massage. The use of RT in trauma resuscitation has generated controversy for many years, and various reviews of outcomes have led to recommendations that highlight which groups of patients are most likely to benefit from the procedure.4, 5, 6

A case report of a survivor of a prehospital thoracotomy performed in 1988 is often quoted as the first prehospital success, but there are reports of a survivor of penetrating heart injury repaired at home in 1902.7,8 A number of physician-led prehospital services have also conducted the procedure for many years, and survivors from penetrating trauma have been regularly reported.9 Resuscitative thoracotomy is now carried out in a high proportion of well-organised trauma receiving hospitals worldwide and commonly where the rate of penetrating trauma is high. A smaller, but increasing, proportion of systems support non-surgeon-delivered and prehospital thoracotomy.

What can the non-specialist operator aim to achieve at operation?

The pathology most amenable to simple intervention is decompression of cardiac tamponade and repair of an underlying cardiac wound. This injury complex is probably responsible for the majority of cases of reported survivors. Other relatively simple interventions include aortic occlusion to optimise cardiac perfusion and reduce sub-diaphragmatic bleeding from other injuries and haemostasis of intrathoracic bleeding. Hilar occlusion is a technique that can be used to control unilateral pulmonary haemorrhage. The pathology of low-energy penetrating wounds is likely to be more amenable to simple surgical techniques than blunt trauma or high-energy penetrating trauma.

What is the role of the anaesthetist/intensivist in RT?

Anaesthetists and intensivists may carry out a number of roles relevant to RT. The most common will be as the anaesthetist on the receiving trauma team where resuscitation and anaesthesia will be delivered. In the event of a successful initial intervention, the patient may require further management in the operating theatre or ICU. In some trauma teams, anaesthetists/intensivists may be trauma team leaders. In these circumstances, decision-making and leadership related to embarking on and conducting the intervention are necessary, and in addition, the team leader should have the ability to perform the procedure. It would always be preferable for a cardiothoracic surgeon to perform an emergency thoracotomy in an operating theatre, but with survival dependent on timelines of only minutes between arrest and pericardial decompression, this is rarely possible. A small number of resuscitative thoracotomies are performed before arrival in a hospital by pre-hospital doctors, and a significant proportion of these doctors have the base specialty of anaesthesia or intensive care medicine.9 This variety of roles makes it essential that anaesthetists have at least knowledge of the indications and practicalities of the procedure, and, for more senior roles, competence in performing the procedure. Training for this procedure is often carried out within trauma networks and external courses are also available.10

Indications for RT

Whenever possible, emergency thoracotomy is best carried out by an experienced surgeon in an operating theatre. Therefore, in the conscious patient requiring an anaesthetic, emergency thoracotomy should be conducted by a surgeon in an operating theatre. However, the main indication for immediate RT is a patient with penetrating chest trauma who is either in a peri-arrest state (who would not tolerate transfer to an operating theatre) or who has been in established cardiac arrest for a short period of time. Resuscitative thoracotomy must be performed immediately to have a chance of success; this means that it should be performed wherever the patient is at the time of deterioration—either pre-hospital or in the emergency department. Unfortunately, these seemingly straightforward criteria can be difficult to establish in the very short time available to make a decision to proceed. The exact time of arrest can be unclear, and the presence of multiple or significant extrathoracic injuries can make the decision more challenging. Aside from obvious penetrating chest trauma, other wounds that can be indications for RT include those in the epigastrium, which may breach the thoracic cavity, and axillary and posterior thoracic wounds, which may not be evident on first look. There are several guidelines that address RT indications. Guidelines from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) are surgically orientated and differentiate patients with and without signs of life.4 Signs of life include pupillary response, spontaneous ventilation, presence of carotid pulse, measurable or palpable arterial pressure, extremity movement, or cardiac electrical activity. These guidelines strongly recommend RT in penetrating thoracic trauma in patients who are pulseless, but still have other signs of life. Resuscitative thoracotomy is only conditionally recommended where, after a short period, a patient with penetrating thoracic trauma presents without signs of life. Resuscitative thoracotomy is also only conditionally recommended in penetrating extrathoracic trauma with or without signs of life. In blunt trauma, the quality of evidence was poor. The EAST conditionally recommends RT in patients who have signs of life after blunt trauma, but conditionally recommend against RT in those without signs of life. Where timings are available, it is suggested that RT performed after 15 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in penetrating trauma and 10 min following blunt trauma is unlikely to be successful.4,5 The 2015 European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines have included a discussion of RT in the treatment of traumatic cardiac arrest.11 The ERC algorithm is more relevant to the non-surgical operator. The algorithm (Fig. 1) and guidelines reflect the US guidelines on duration of CPR: 10 min for blunt and 15 min for penetrating trauma, but suggest a 10 min cut-off for commencing RT in the traumatic cardiac arrest treatment algorithm. The position of RT, towards the end of the ERC algorithm, may reflect the fact that penetrating trauma is uncommon in many European countries, and RT is only performed rarely. Other interventions for the treatment of traumatic cardiac arrest take priority in the algorithm, but an effective trauma team may well achieve these interventions simultaneously. However, if RT is going to be performed in a pulseless patient after trauma, the time taken to start the intervention must be very short. Progress through the algorithm to RT must be very rapid in order for RT to have any reasonable chance of success. The ERC algorithm suggests that four Es must be met when considering RT: these are expertise in a team operating within a governance framework, adequate equipment, an appropriate environment to operate, and only commencing RT when a short time from cardiac arrest has elapsed.

Fig 1.

Traumatic cardiac arrest algorithm. European Resuscitation Council guidelines 2015.11 Reproduced with permission. ALS, advanced life support.

Expertise and environment

Whilst it would always be preferable for a cardiothoracic surgeon to perform an emergency thoracotomy in an operating theatre, the clamshell technique is suitable for non-surgeons, using basic equipment and with the aim of addressing limited pathology. It also provides good access to and exposure of thoracic organs. The operating team should undergo regular training, ideally simulation based, to ensure they are able to effectively carry out the thoracotomy. A standard operating procedure should be produced and standardised equipment available.

Equipment

The equipment usually supplied to perform a thoracotomy in the operating theatre is too complex to replicate in the emergency department for RT. The equipment required to address limited pathology by non-specialist operators is relatively basic. It should be simple and low-tech, requiring minimal experience to use and minimal time to set up. It should be prepacked and readily available in emergency departments or prehospital settings. A generic list of the essential equipment is listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Essential equipment for RT.

-

(i)

Skin preparation materials

-

(ii)

Scalpel

-

(iii)

Blunt forceps (curved and straight)

-

(iv)

Large scissors for general dissection

-

(v)

Serrated wire and handles for cutting through sternum

-

(vi)

Self-retaining rib spreaders

-

(vii)

Clamps for haemorrhage control (small and large)

-

(viii)

Scissors for cutting the pericardium (small and large)

-

(ix)

Skin stapler and sutures

-

(x)

Large surgical gauze swabs

Alt-text: Box 1

Elapsed

Resuscitative thoracotomy in the pulseless patient is a time-critical procedure. Resuscitative thoracotomy should be commenced within 10 min of cardiac arrest and certainly within 15 min to have a reasonable chance of success.

Technique

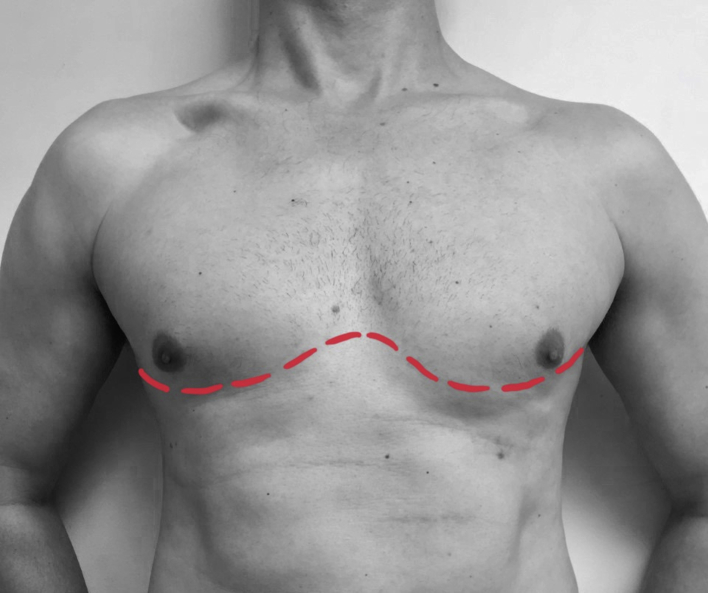

The largest series of prehospital thoracotomies has been performed at London's Air Ambulance in the UK. The technique used has been well described and is designed for non-surgeons using basic equipment and aimed at addressing limited pathology.12,13 The technique is also well suited to the emergency department thoracotomy. A ‘clamshell’ incision (Fig. 2) is recommended because it is rapid and easy to perform and gives an excellent view and access to the heart and mediastinum.12, 13, 14 The technique is summarised in Box 2.

Fig 2.

‘Clamshell’ incision.

Box 2. RT technique.

Resuscitative clamshell thoracotomy technique (adapted from Rehn and colleagues13).

-

(i)

Position the patient: Supine with 360 degrees of access. Intubation, ventilation, i.v. access, etc. are simultaneously performed by team members other than the operator to prevent delaying thoracotomy.

-

(ii)

Prepare: Wear sterile gloves and restrict aseptic technique to rapid application of skin preparation. There may not be time for formal surgical draping.

-

(iii)Opening the chest:

-

(a)Perform bilateral thoracostomies in the mid-axillary line, fourth intercostal space using scalpel and blunt forceps.

-

(b)Make a clamshell skin incision in the fourth interspace joining the thoracostomy wounds (Fig. 2). Insert two fingers into thoracostomy (holding the lung out of the way) whilst extending the thoracostomy wounds on both sides up to the sternum using heavy scissors. The sternum can usually be divided with scissors. If not, pass blunt forceps behind the sternum and pull the serrated wire of a Gigli saw behind the sternum. Attach wire to the saw handles and divide the sternum horizontally with a few saw strokes.

-

(c)The incision in the intercostal space is then extended posteriorly to the posterior axillary line to allow full chest opening in a ‘clamshell’ fashion. A self-retaining rib spreader is inserted and used to maximise the exposure of the heart.

-

(a)

-

(iv)

Release of cardiac tamponade: Blunt forceps are used to raise a ‘tent’ of pericardium on the anterior surface of the heart. The pericardium is opened with surgical scissors vertically and the incision extended to expose the heart. Vertical incision minimises the risk of phrenic nerve damage. Evacuate blood clots by hand from the open pericardium. The heart may fibrillate or beat spontaneously after pericardial decompression.

-

(v)

Cardiac repair: Cardiac wounds should be sutured or stapled with skin staples or occluded with a finger. Wounds adjacent to coronary arteries should be sutured with caution to avoid occlusion. Foley catheters have been used to occlude larger defects, but risk reducing volume for cardiac filling and the potential for the balloon to pull out and enlarge the hole. Should ventricular fibrillation be observed, the rib spreader should be removed, the chest closed, electrodes applied to the chest wall, and defibrillation carried out. Alternatively, if internal paddles are immediately available, internal defibrillation can be used with the first shock at 10 J increasing to 20 J if required. Either peripheral i.v. access or central venous access must be established, especially for patients with hypovolaemia.

-

(vi)

Cardiac massage: If there is no spontaneous cardiac contraction, attempt stimulation by flicking with a finger. If this is ineffective, begin cardiac massage, ensuring the heart has sufficient volume to allow effective massage. A two-handed technique should be used ensuring that the heart is horizontal and not kinked on its vascular pedicle. Blood is ‘milked’ from the apex upwards, initially at a slow rate allowing the heart to fill, gradually increasing to a rate of 80 beats min−1. Simultaneously, an assistant can compress the descending aorta against the spinal column to raise aortic root pressure, enhance coronary blood flow, and limit sub-diaphragmatic haemorrhage.

-

(vii)

Anaesthesia: If the procedure is successful, the patient may begin to wake up so be prepared to provide immediate anaesthesia. An anaesthetic agent with minimal cardiac depression should be used and ketamine is frequently the agent of choice.

-

(viii)

After restoration of circulation: Bleeding may occur particularly from the internal mammary and intercostal vessels. Larger bleeding vessels may require control with haemostatic clamps. Once perfusion has been restored, the patient should be moved to a hospital operating theatre for definitive repair.

Alt-text: Box 2

RT outcomes

The key factors determining survival after RT are the nature and extent of the injuries sustained and the time elapsed after cardiac arrest. Resuscitative thoracotomy is ideally performed before cardiac arrest or in the few minutes after it has occurred. The survival rates for blunt trauma are much lower than for penetrating trauma, and blunt traumatic injury may require a higher level of surgical skill to repair.4,5,15 Resuscitative thoracotomy following gunshot wounds has much lower reported survival rates when compared with those following knife wounds.4,16 A single low-energy wound to the heart with associated cardiac tamponade is the most amenable pathology for non-surgeon intervention. The 2015 ERC guidelines estimated survival rates for RT of approximately 15% for patients with penetrating wounds and 35% for patients with a penetrating cardiac wound. In contrast, survival from RT following blunt trauma was dismal, with reported survival rates of only 0–2%. In 2015, the EAST completed a systematic review of RT.4 Seventy-two studies were included, providing data on 10,238 patients who underwent RT. Survival was reported with and without RT (Table 1). These data confirm that the indication of penetrating trauma and time to RT are key factors in survival rates. However, it is important to note that the cases included were predominantly RT performed within hospitals by US trauma surgeons; this may limit the generalisability of these outcomes to European practice. This is one of few reviews that attempted to estimate neurological outcomes in addition to survival; 18% survival rates were reported amongst patients who underwent rapid prehospital thoracotomy for single cardiac knife wounds. Results for blunt trauma were poor.9 Paediatric RT is performed uncommonly and usually on older children. Indications and techniques are the same as for adults, and published results suggest similar outcomes to adult RT.17

Table 1.

Survival after RT (majority operated on by US trauma surgeons).4

| Type of trauma | Signs of life | Survival without RT (%) | Survival with RT (%) | Neurologically intact without RT (%) | Neurologically intact with RT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penetrating thoracic | With | 2.8 | 21.3 | 2.5 | 11.7 |

| Penetrating thoracic | Without | 0.2 | 8.3 | 0.18 | 3.9 |

| Penetrating extrathoracic | With | 1.7 | 15.6 | 1.5 | 16.5 |

| Penetrating extrathoracic | Without | 0.1 | 2.9 | 0.09 | 5.0 |

| Blunt | With | 0.5 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Blunt | Without | 0.001 | 0.7 | 0.0006 | 0.1 |

Considerations for anaesthesia

Resuscitative thoracotomy is usually commenced on patients in cardiac arrest, and therefore, anaesthetic agents are not given before the procedure. Where return of circulation is achieved, the patient may begin to wake up and require immediate anaesthesia. An anaesthetic agent with minimal cardiac depression should be used. Ketamine is frequently the agent of choice, and dosing should be carefully titrated to effect. An initial dose of approximately 1 mg kg−1 is often given i.v.; lower doses may be indicated if there is severe cardiovascular compromise. When the procedure is carried out on a patient in a peri-arrest state, a rapid sequence induction should be performed before the incision, using reduced doses of i.v. anaesthetic agent, with or without an opioid. The recommended anaesthetic technique is the same as that for the severely hypovolaemic patient after trauma or ruptured aortic aneurysm. In UK practice, the combination of fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium is commonly used. Fentanyl should be given with caution, as the sympatholytic effect of fentanyl can lead to a deterioration in cardiovascular stability in the patient who is profoundly unstable and hypovolaemic. If RT is successful and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) occurs, the considerations for anaesthesia change. Correction of hypovolaemia with blood products and treatment with tranexamic acid and vasopressors may be necessary. The patient may require further surgery in the operating theatre, in which case transfer to an operating theatre and management of anaesthesia for cardiothoracic surgery with an open chest are indicated. Management of bleeding and coagulopathy is a priority, and prophylactic antibiotics should be administered as per local hospital guidelines. A balanced transfusion protocol of packed red blood cells to fresh frozen plasma in a ratio of 1:1 with additional cryoprecipitate and platelets is usually indicated as part of local major haemorrhage protocols. Point-of-care coagulation testing can be used to guide product use. Patients requiring massive transfusion often require correction of electrolyte imbalances (e.g. hyperkalaemia and hypocalcaemia). The use of a warmed rapid infuser is essential as these patients are often profoundly hypothermic. A temperature of less than 32°C reduces the likelihood of ROSC and increases the risk of arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation. A minority of survivors will be haemodynamically stable and wake rapidly, but most will require intensive care management. There should be an emphasis on the management of postoperative traumatic injury and post-cardiac arrest brain injury, combined with the response to systemic ischaemia and reperfusion. Myocardial dysfunction may result from cardiac hypoperfusion, direct cardiac injury or coronary artery injury (either from penetrating trauma or cardiac repair).

Resuscitative thoracotomy is increasingly being performed in the prehospital setting because of the time-critical nature of the procedure. Therefore, patients may present to the emergency department after an RT. Emergency departments are usually pre-alerted about these cases, allowing time for preparation. This time can be used to activate major haemorrhage protocols, priming and warming rapid infusers with blood products, and liaising with the operating theatre team to reserve an operating theatre and to request the presence of a cardiothoracic surgeon if available.

Other considerations

Resuscitative thoracotomy brings a number of logistical and operational considerations that are common to trauma practice, but perhaps particularly relevant to this procedure. The risks to providers include sharps injuries from fractured ribs, needles, surgical instruments, and blood splash contamination. The use of adequate personal protective equipment and keen awareness of sharps are mandatory. Risks can be reduced by having only the operator's hands in the operating field whenever possible.

Resuscitative thoracotomy can appear to be a dramatic and bloody resuscitation intervention particularly in emergency departments, where it is only carried out rarely. A routine ‘hot debrief’ after the case can provide explanation and reassurance to all staff of why the intervention was carried out and also identify opportunities for improvement.

Penetrating trauma often results in criminal investigation, and although treatment is the priority, the operating team should be aware of forensic considerations, including preservation of clothing, possessions and other evidence. Meticulous documentation is necessary, and statements for the police and (in England and Wales) the coroner are often required.

Resuscitative thoracotomy should always be subject to trauma network governance process. A standard operating procedure should be produced and appropriate training and standardised equipment in place. The standard operating procedure and equipment should be developed by a group, which includes representatives from all relevant groups, including cardiothoracic surgery.

Conclusions

Resuscitative thoracotomy is increasingly performed in the UK in parallel with an increase in the incidence of penetrating trauma. Historically, RT has been a common practice in the USA, but survival data have led to a more selective approach. Resuscitative thoracotomy should be considered in cardiac arrest in penetrating chest trauma shortly before, or in the period shortly after, cardiac arrest. Survival rates after RT for other indications, such as blunt trauma and extrathoracic penetrating trauma, are lower; these cases are less amenable to intervention by non-surgeons. Resuscitative thoracotomy in the patient who is pulseless is a time-critical procedure. It should be commenced within 10 min of cardiac arrest and certainly within 15 min to have a reasonable chance of success. Anaesthesia is required where the procedure is performed before cardiac arrest or after ROSC is achieved. Anaesthetists and intensivists may also work as trauma team leaders and in pre-hospital medicine, and so may also be required to perform the procedure. All emergency departments in major trauma centres are required to be able to provide immediate RT. It is therefore essential that anaesthetists and intensivists have a thorough understanding of RT.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) are accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home for subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Skylar PaulichMRCP FRCA FFICM is a specialty registrar in intensive care and anaesthesia at North Bristol NHS Trust.

David LockeyMD (Res) FRCA FFICM FIMC RCS(Ed) is a consultant in intensive care medicine and anaesthesia at North Bristol NHS Trust, and chairman of the Faculty of Pre-hospital Care at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. His research interests are in pre-hospital trauma care and resuscitation. He is an honorary professor at Bristol University and the Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University, London.

Matrix codes: 1B04, 2A02, 3A10

References

- 1.NHS standard contract for major trauma service. NHS; England: 2013. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/d15-major-trauma-0414.pdf D15/S/a (gateway reference 01365) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck C.S. Wounds of the heart. Arch Surg. 1926;13:205. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blatchford J.W., III Ludwig Rehn: the first successful cardiorrhaphy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;39:492–495. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seamon M.J., Haut E.R., Van Arendonk K. An evidence-based approach to patient selection for emergency department thoracotomy: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:159–173. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burlew C.C., Moore E.E., Moore F.A. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: resuscitative thoracotomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1359–1363. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318270d2df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph B., Khan M., Jehan F. Improving survival after an emergency resuscitative thoracotomy: a 5-year review of the Trauma Quality Improvement Program. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3 doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wall M.J., Jr., Pepe P.E., Mattox K.L. Successful roadside resuscitative thoracotomy: case report and literature review. J Trauma. 1994;36:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster R. Luther Leonidas Hill Jr. Available from: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2949 (accessed 2 January 2020).

- 9.Lockey D.J., Brohi K. Pre-hospital thoracotomy and the evolution of pre-hospital critical care for victims of trauma. Injury. 2017;48:1863–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Surgeons of England Pre-hospital and emergency department resuscitative thoracotomy. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/education-and-exams/courses/search/prehospital-and-emergency-department-resuscitative-thoracotomy/ Available from:

- 11.Truhlář A., Deakin C.D., Soar J. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances section. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148–201. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise D., Davies G., Coats T. Emergency thoracotomy: “how to do it”. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:22–24. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.012963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehn M., Davies G., Lockey D.J. Resuscitative thoracotomy: a practical approach. Surgery. 2018;36:424–428. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaris A.N., Simms E.R., Prat N. Clamshell incision versus left anterolateral thoracotomy. Which one is faster when performing a resuscitative thoracotomy? The tortoise and the hare revisited. World J Surg. 2015;39:1306–1311. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz-Drost S., Merschin D., Gümbel D. Emergency department thoracotomy of severely injured patients: an analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU®. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019,Sep 13 doi: 10.1007/s00068-019-01212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branney S.W., Moore E.E., Feldhaus K.M., Wolfe R.E. Critical analysis of two decades of experience with post injury emergency department thoracotomy in a regional trauma center. J Trauma. 1998;45:87–94. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen C.J., Valle E.J., Thorson C.M. Pediatric emergency department thoracotomy: a large case series and systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]