Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Recognise a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) as a cause of neonatal respiratory distress and describe the early supportive management steps

-

•

Identify poor prognostic features for patients with a CDH

-

•

Define the aims of medical management

-

•

Explain the most likely intraoperative problems during surgery for CDH.

Key points.

-

•

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a rare birth defect affecting 1 in 3600 registered births across Europe.

-

•

Key clinical features are lung hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension.

-

•

CDH is not a neonatal surgical emergency.

-

•

A multidisciplinary approach to optimal timing of surgery is critical.

-

•

Cardiac abnormalities occur in 14% of cases. Defect size and presence of cardiac abnormalities are strong predictors of mortality.

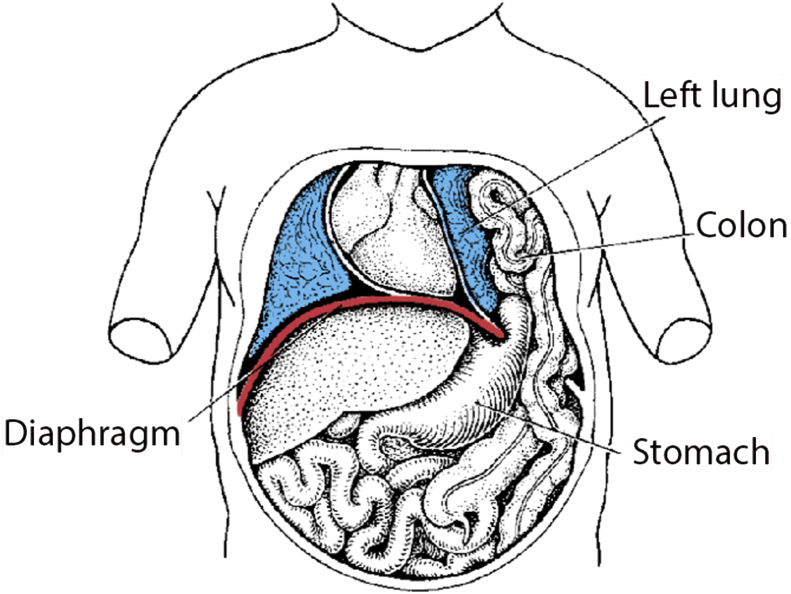

A congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) occurs when a defect in the diaphragm allows abdominal organs to protrude into the thoracic cavity (Fig. 1). It affects approximately 1 in 3600 registered births1 and is a potentially life-threatening condition, the severity of which is primarily related to the extent of lung hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension.

Fig 1.

A left-sided hernia. From Langman's Essential Medical Embryology, 13th edition.8 Reproduced with kind permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

Advances in management strategies include protective ventilation, careful timing of surgery, the judicious use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and the introduction of both thoracoscopic and fetal intervention, but it remains a challenging condition to treat successfully with overall mortality rates still around 30%.2

Aetiology

The exact trigger for development of the diaphragmatic defect is currently undetermined. Traditionally it was assumed that herniation of abdominal organs into the chest directly inhibits normal lung development. However, the occurrence of bilateral pulmonary hypoplasia in unilateral diaphragmatic hernias has led to the proposal of other theories.

The ‘dual hit hypothesis’ has evolved from rodent models, and suggests that pulmonary hypoplasia is the primary disturbance, occurring as a result of genetic and environment factors. This then hampers the formation of the diaphragm; the consequent protrusion of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity then further hinders lung development on that side—the second ‘hit’.3

Associations

Approximately 10% of patients have associated genetic or chromosomal abnormalities including trisomy 13, 18 and 21, Fryns syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Beckwith–Wiedemann and CHARGE Syndrome.1 Moreover, almost a third of babies born with CDH have one or more structural abnormality. The most common are those affecting the cardiovascular system (14%; Table 1) although genitourinary (7%), limb (5%), central nervous system (5%) and palatal (2%) anomalies also occur.1

Table 1.

The relative frequency of cardiac abnormalities in patients with CDH1

| Cardiac defect | Relative frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Ventricular septal defect | 29 |

| Atrial septal defect | 26 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 8 |

| Hypoplastic left heart | 7 |

| Other | 31 |

Severity

The overall severity of a CDH may be described by the classification in Table 2.4

Table 2.

Classification of CDH according to size of defect

| Type | Defect |

|---|---|

| A | Small defects entirely surrounded by muscle |

| B | <50% chest wall with absent diaphragmatic tissue |

| C | >50% chest wall with absent diaphragmatic tissue |

| D | Complete absence of hemidiaphragm |

Accurate prediction of severity and thus survival of infants with CDH remains a challenge (Table 3). The absence of liver herniation is the most reliable antenatal predictor of survival.5 Gestational age at diagnosis is also important as it is an early indicator of defect size – and this has been shown to be one of the most significant predictors of mortality. Infants with a near absence of the diaphragm have been found to have a survival rate of 57% compared with 95% in those who have a defect small enough for a primary repair.2

Table 3.

Antenatal and postnatal prognostic indicators in CDH

| Indicators of a poor prognosis |

|---|

| Antenatal |

| Liver herniation |

| Early gestational age at diagnosis |

| Postnatal |

| Large defect size |

| Cardiac abnormalities |

| Chromosomal abnormalities |

| Severe pulmonary hypertension |

| Low birth weight |

| Low Apgar score at 5 min |

| Small contralateral lung |

| Bilateral CDH |

A validated scoring system has been proposed based on various measurements, including:

-

(i)

birth weight <1.5 kg,

-

(ii)

Apgar score at 5 mins <7,

-

(iii)

presence of chromosomal abnormality,

-

(iv)

presence of major cardiac abnormality, and

-

(v)

suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension on echocardiography.

This scoring system enables patients to be stratified into low (<10%), intermediate (∼25%) or high risk (∼50%) mortality groups.6 Cardiac defects have been shown to worsen outcome regardless of the severity of the hernia: 99% survival compared with 88% in those with type A defects, and 58% compared with 39% survival in those with type D defects.4 The presence of a small contralateral lung or a bilateral CDH are also poor prognostic signs. The small number of right-sided herniae makes it difficult to be sure about their relative prognosis, but they have recently been associated with an increase in need for a patch repair and a higher recurrence rate.7

Pathophysiology

Embryology

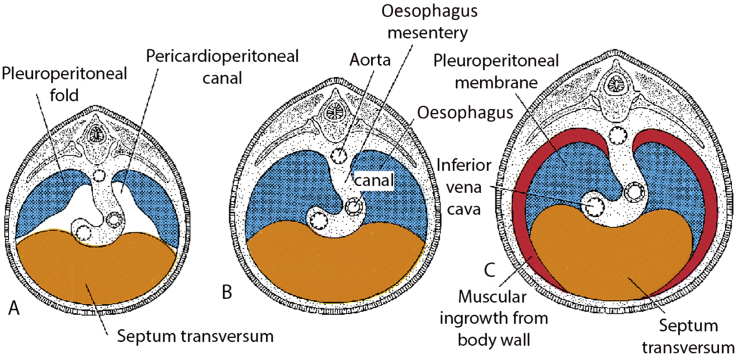

To understand how these herniae form, it is necessary to appreciate the embryological development of the diaphragm. On approximately day 22 of embryonic development, the septum transversum extends from the anterior aspect of the body cavity. Pleuroperitoneal folds then originate from the lateral sides of the body cavity at the beginning of the 5th week. By the 7th week, the septum transversum and pleuroperitoneal folds extend inwards to fuse with each other and the mesentery of the oesophagus to form the initial complete diaphragmatic structure and divide the thoracic and abdominal cavities. By the 16th week of gestation, the muscular component of the diaphragm begins to develop8 (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Embryological development of the diaphragm. From Langman's Essential Medical Embryology, 13th edition.8 Reproduced with kind permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

The lung parenchyma of neonates with a CDH is also abnormal. There is abnormal differentiation of type 2 pneumocytes, and thickening of intrapulmonary arteries leading to pulmonary hypertension. There is also an exaggerated response to vasoactive substances with endothelin 1 being shown to be dysregulated leading to worsening pulmonary hypertension. Endothelin 1 concentrations in plasma have been shown to be higher within the first month of life in babies that subsequently did not survive or were discharged on oxygen compared with those discharged on room air.9

Types

The majority of defects are left sided with only 20% of cases affecting the right side. Bilateral diaphragmatic herniae are very rare.8 There are two main types of CDH: Bochdalek and Morgagni.

Bochdalek

Bochdalek herniae occur in 95% of cases. They result from a failure of fusion of the pleuroperitoneal folds and are consequently posterolateral.

Morgagni

Morgagni hernias make up the remaining 5%. They result from herniation through the foramen of Morgagni—a small defect within the septum transversum, posterior to the sternum. They are therefore retrosternal or parasternal, usually smaller and right sided in 90% of cases. Morgagni herniae are associated with a better outcome.8

Antenatal management

Diagnosis

Approximately 50% of cases are diagnosed antenatally as a result of routine ultrasound screening.10 Sensitivity of screening improves with advancing gestation, the presence of associated abnormalities, and with an experienced ultrasonographer.10 Right-sided herniae are more difficult to diagnose as liver and fetal lung can look very similar on ultrasound. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging can be used to confirm a diagnosis. Once a CDH has been identified, high resolution ultrasound should be used to grade severity in order to aid parental counselling and potentially select those who may benefit from experimental intrauterine intervention. This usually includes measurements of lung volume and the position of the liver as well as looking for significant comorbidity.

Fetal surgery

Fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) is an experimental procedure that has been undertaken in pregnancies with a predicted poor prognosis. Its aim is to promote lung growth and therefore limit the evolving pulmonary hypoplasia.

Fetal lungs produce fluid; preventing the efflux of this fluid by temporarily occluding the trachea with a balloon has been shown to cause stretching of the lung tissue and increased production of growth factors and thus accelerated lung growth. This has been shown to substantially improve short-term mortality rates in those with a poor prognosis, but is complicated by the risk of preterm delivery.11 The TOTAL trial (Tracheal Occlusion To Accelerate Lung growth—NCT01240057) is currently recruiting patients in Europe.

Postnatal management

Diagnosis

If not diagnosed antenatally, the initial signs of a diaphragmatic hernia will usually occur soon after birth with respiratory distress, possibly in the presence of a scaphoid abdomen.

A chest radiograph will typically show abdominal organs within the thoracic cavity. (Fig 3, Fig 4).

Fig 3.

Chest radiograph of a left CDH, showing significant mediastinal shift. The nasogastric tube is in the stomach, which has protruded into the left thoracic cavity.

Fig 4.

Chest radiograph of a right CDH with significant liver herniation. An umbilical vein catheter is seen projecting into the thoracic cavity on the right side. ECMO cannulae are also visible.

Medical treatment

Patients born with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing respiratory distress require resuscitation and medical stabilisation before definitive surgical repair.

The vast majority of patients will require tracheal intubation and artificial ventilation immediately after delivery; ideally mask ventilation should be avoided to prevent gastric insufflation. The insertion of a nasogastric tube with continuous or intermittent suction may help to decompress the bowel and relieve pressure on the lungs. Only those babies predicted to have good lung development (i.e. with a left-sided defect, no liver involvement, and good lung growth on antenatal scans) should be considered for a trial without intubation.12

Early echocardiography will reveal the degree of cardiac impairment, concurrent defects, pulmonary hypertension and presence of right to left shunting and thus guide medical treatment.

Pharmacological

The mainstays of pharmacological therapy are the optimisation of adequate gas exchange, minimisation of pulmonary hypertension, and maintenance of organ perfusion in neonates with significant haemodynamic instability.

Pulmonary vasodilators

Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide is commonly used in the management of pulmonary hypertension secondary to a variety of conditions; however when used in intensive care for babies with a CDH, it does not seem to improve outcome and may be associated with increased mortality rates.13 When it is used, response to treatment should be assessed by echocardiography and if it has not made a significant difference it should be stopped.

Other agents

In cases of severe refractory pulmonary hypertension, intravenous sildenafil or prostacyclin have been suggested by the CDH EURO Consortium as additional therapy that may improve the clinical condition.12

In addition, prostaglandin E1 can be given to maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus. This encourages a right to left shunt, thus worsening postductal oxygen saturations, but in severe cases can help offload the right ventricle and maintain cardiac output.12

Inotropic/vasopressor drugs

Inotropic or vasopressor drugs are widely used in the management of CDH to maintain adequate organ perfusion in the context of systemic vasodilatation or impaired cardiac function. They can also decrease right-to-left shunting, thereby improving post ductal oxygen saturations, although there is no evidence that this confers any significant survival benefit. The choice of agent is often guided by echocardiographic findings and individual preference but may include noradrenaline, dopamine, dobutamine and milrinone.

Neuromuscular blocking agents

Neuromuscular blocking agents can aid ventilator synchrony and optimise chest wall compliance but their use should be restricted to situations where ventilation is increasingly challenging.12

Ventilation

Historically, aggressive ventilation was used to induce hypocapnia and alkalosis and thereby reduce pulmonary hypertension; however, protective ventilation strategies that avoid further injury to damaged lung tissue have reduced mortality in CDH. The CDH EURO Consortium advocates aiming for the limitation of peak inspiratory pressures to 25 cm H2O with PEEP kept at 3–5 cm H2O and allowing permissive hypercapnia.12

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation

High frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) is classically used as a rescue strategy when hypoxia and severe hypercapnia persist despite maximal conventional ventilation. The VICI trial (2016) randomised 171 neonates to conventional ventilation or HFOV as the initial mode of ventilation and found no significant difference in mortality, but those who had conventional ventilation were ventilated for shorter periods, needed less nitric oxide, sildenafil and ECMO, and had lower requirements for inotropic drugs.14

ECMO

ECMO is provided as a rescue therapy before surgical correction in neonates where conventional therapy is failing. It was first used for CDH in the late 1970s.15 Since then, several trials have looked at the effect of ECMO on outcome in CDH. This work, however, has been confounded by advances in antenatal diagnosis and counselling, more protective modes of ventilation, delayed surgery and differences in selection criteria between centres.15 There is a degree of consensus however that ECMO does confer a survival advantage in the most severe cases of CDH (i.e. those with a predicted mortality of more than 80%), however its value in more moderate disease is less clear because of the high incidence of ECMO-related complications.15

Criteria for ECMO in CDH

The CDH EURO Consortium recommends that ECMO is considered in the following situations:

-

(i)

peak inspiratory pressure >28 cm H2O on conventional ventilation needed to achieve O2 saturation >85%,

-

(ii)

PaCO2>9.0 kPa (67 mm Hg) despite optimum ventilation,

-

(iii)

pre or post ductal saturations consistently ≤80% or ≤70%, respectively,

-

(iv)

pH<7.15 or serum lactate ≥5 mmol litre−1, and

-

(v)

refractory hypotension despite maximal fluid and inotropic therapy with urine output <0.5 ml kg−1 h−1 for at least 12–24 h.12

It is acknowledged however that there is weak evidence to support these recommendations.

Surgical repair

Surgical correction of a CDH involves returning the abdominal organs from the chest into the abdominal cavity. The diaphragmatic defect is then closed either by a primary repair (whereby the defect is directly sutured closed) or by inserting a patch to close larger defects. Surgery can be open or thoracoscopic.

Open surgery

The open surgical approach is usually via a subcostal incision. Open surgery is necessary for larger defects, particularly in the presence of liver herniation, and for sicker patients requiring higher ventilatory or cardiovascular support.

Occasionally it may not be possible to close the abdominal wall after open surgery without compromise to ventilatory or cardiovascular stability and the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome. This is particularly true where the hernia is large and the abdominal cavity is small. The viscera can therefore be covered and the patient left with a laparostomy, with definitive closure occurring at a later date.

Thoracoscopic surgery

This minimally invasive approach has many theoretical advantages, including less postoperative pain, shorter ventilation time, earlier feeding, shorter hospitalisation, and less scarring. Thoracoscopic surgery does, however, take longer and results in higher PaCO2, more severe acidosis, and decreased cerebral oxygenation saturations,16 the long-term significance of which are not clear. A requirement for higher ventilatory pressures may also worsen lung injury and pulmonary hypertension. In addition, thoracoscopic surgery is associated with higher rates of recurrence, particularly in the context of ongoing vasopressor therapy or HFOV,17 and there is little evidence to suggest an improvement in mortality.18

Careful patient selection is therefore imperative in determining the appropriate surgical approach for each patient. This should involve a balanced discussion between surgical, anaesthetic, intensive care teams and parents based on both local experience and the individual risks and benefits of each case.

Timing of surgery

Historically, CDH repair was treated as a surgical emergency. However, the degree of pulmonary hypoplasia is the major influence on prognosis and emergency surgery therefore confers little benefit. There is much debate but little consensus within the literature regarding the optimal timing of surgery.

Recommendations from the CDH EURO Consortium state that the following physiological parameters should be met before surgery:

-

(i)

mean arterial pressure normal for gestation,

-

(ii)

preductal oxygen saturation consistently 85–95% on FiO2 <0.5,

-

(iii)

lactate below 3 mmol litre−1, and

-

(iv)

urine output more than 1 ml kg−1 h−1 12.

These recommendations do, however, acknowledge that repair on ECMO is a viable treatment strategy in the context of appropriate patient selection.

Surgical repair on ECMO

Surgical repair in patients on ECMO is controversial. The risks are higher (particularly bleeding) and the CDH Study Group have reported 49% survival in a cohort of more than 3600 neonates.19 Some centres are now focusing on operating within the first 72 h of starting ECMO (on average 4.5 days earlier than the patients in the CDH Study Group cohort) and have reported better survival rates with less time required on ECMO after surgery. In one series, 73% of those undergoing surgical repair within the first 72 h of ECMO survived, compared with 50% of those repaired after 72 h, and 64% of those repaired after decannulation.20 Others, however, have reported 100% survival rates for repair after decannulation compared with 44% during ECMO, supporting the strategy of delaying repair.21

Unfortunately, many of the studies have produced conflicting results and it does not help that most have small sample sizes, often around 50–100 patients. The picture is further complicated by the fact that many of those having a late repair on ECMO were unable to be weaned off, putting them in the highest disease severity category and hence less likely to survive regardless of the timing of surgery.15

Perioperative management

Decision to operate

There is little consensus regarding the best time to operate on these patients but it is not a surgical emergency. As such, these cases should be performed during normal working hours. Nevertheless, the window of opportunity for these children may be relatively small. The decision to operate should involve close cooperation between the anaesthetists, surgeons, intensivists, paediatricians and parents. Cardiorespiratory function should be stable with clinical evidence that pulmonary hypertension is resolving supported by findings on echocardiography.

Preoperative assessment

A thorough anaesthetic review should involve the standard neonatal assessment including:

-

(i)

antenatal and perinatal history,

-

(ii)

glucose and fluid management,

-

(iii)

cranial ultrasound results,

-

(iv)

assessment of adequacy of arterial and venous access (possibly including a long line or central venous catheter),

-

(v)

endotracheal tube size and position along with the method used to secure it, and

-

(vi)

blood results and availability of blood products.

Important details pertaining specifically to these patients include:

-

(i)

previous or ongoing need for HFOV or ECMO (and a history of any complications of treatment),

-

(ii)

inotrope requirements,

-

(iii)

pulmonary hypertension management,

-

(iv)

current ventilator settings with careful attention to ongoing trends in support, and

-

(v)

arterial blood gas results.

Finally, relevant surgical factors should be reviewed such as the side and position of the defect (Morgagni vs Bochdalek), anticipated size, and degree of liver herniation if present.

Intraoperative challenges

Once a decision has been made to go to theatre, intraoperative management requires excellent communication amongst the whole team. It is even more important than usual to be aware of what the surgeons are doing at all times, as this will directly impact on the baby's physiology and therefore anaesthetic management. Any difficulties with maintaining stability need to be effectively fed back to the surgical team. Some centres in the UK routinely have two consultant anaesthetists present; this can be very helpful but may also bring potential problems and roles should be clearly established from the start.

The most common intraoperative problem is difficulty with ventilation, in particular the inability to adequately control PaCO2—especially during a thoracoscopic repair where the hemithorax has been insufflated with CO2. Approximately 30% of exhaled CO2 in these cases comes from the pneumothorax.16 It is important to keep circuit dead space to a minimum (e.g. by removing the angle piece and using a neonatal circuit if available). End-tidal CO2 traces in neonates are notoriously unreliable because of their small tidal volumes and transcutaneous CO2 monitoring can be helpful to rapidly identify trends in PaCO2. In case of difficulty, simple potential causes should not be forgotten such as kinking of the ETT or a need for suctioning. Compliance of the lungs can be assessed with a T-piece and periods of manual hyperventilation may be required to reduce hypercapnia. It may be necessary to convert a thoracoscopic repair to an open procedure.

Inhaled nitric oxide should be available in theatre in case of suspected worsening pulmonary hypertension that does not respond to the usual measures of hyperventilation to reduce PaCO2, increasing the FiO2, management of acidosis, maintenance of adequate warming, and analgesia.

Haemodynamic stability should also be closely monitored. Over-hydration should be avoided as it may lead to pulmonary congestion in the postoperative period. In cases of cardiovascular instability, it may be necessary for vasopressors or inotropes to be commenced to maintain organ perfusion and manage intraoperative shunting.

Postoperative management

The patient will need to be transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit, fully ventilated with ongoing sedation. Compliance and gas exchange tend to deteriorate in the immediate postoperative period. Pulmonary hypertension may persist, potentially mandating further ECMO. It is also important to be vigilant for bleeding, chylothorax, early recurrence of the hernia or the development of a patch infection.

Long-term sequelae

The overall survival rate of CDH is 69%2; however, up to 87% of surviving children will go on to experience long-term morbidity related to their CDH. The extent of these conditions often relates to initial disease severity.22

-

(i)

Respiratory

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (34%)

Chest deformity (40%)

-

(ii)

Gastrointestinal

Reflux (30%)

Failure to thrive (20%)

-

(iii)

Neurological

Sensorineural hearing loss (50%)

Cognitive impairment (up to 70%)

Long-term management of these conditions requires regular input of a multidisciplinary team.

Conclusion

CDH remains one of the most challenging conditions for paediatric anaesthetists, surgeons and intensivists to treat successfully. Despite advances in ventilation, extracorporeal organ support and surgical approaches, rates of mortality are still significant.

CDH is not a neonatal surgical emergency and the clinical situation must be carefully assessed in order to determine the optimal timing of corrective surgery for these high-risk patients.

There is still a high degree of uncertainty as to how best to manage these patients, especially regarding the optimal timing of surgery (particularly when ECMO is required) and the role of thoracoscopic surgery.

Declaration of interest

None declared.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) can be accessed at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Michelle Quinney FRCA is a specialty trainee in anaesthesia who has completed 12 months at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and plans to pursue a career in paediatric anaesthesia.

Hugo Wellesley FRCA MA is a Consultant at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the UCH Institute of Child Health. His clinical interests include general surgery for neonates and children. He is also member of the hospital's Clinical Ethics Committee.

Matrix codes: 1A01, 2D01, 3D00

References

- 1.McGivern M.R., Best K.E., Rankin J. Epidemiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F137–F144. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lally K.P., Lally P.A., Lasky R.E. Defect size determines survival in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e651–e657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keijzer R., Liu J., Deimling J., Tibboel D., Post M. Dual-hit hypothesis explains pulmonary hypoplasia in the nitrofen model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lally K.P., Lasky R.E., Lally P.A. Standardized reporting for congenital diaphragmatic hernia—an international consensus. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:2408–2415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullassery D., Ba'ath M.E., Jesudason E.C., Losty P.D. Value of liver herniation in prediction of outcome in fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:609–614. doi: 10.1002/uog.7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brindle M.E., Cook E.F., Tibboel D., Lally P.A., Lally K.P.A. Clinical prediction rule for the severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernias in newborns. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e413–e419. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaumier C.K., Beres A.L., Puligandla P.S., Skarsgard E.D. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with right congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadler T.W. Langman's Essential Medical Embryology. 13th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health; Philadelphia: 2014. The gut tube and the body cavities; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller R.L., Tacy T.A., Hendricks-Munoz K. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: endothelin-1, pulmonary hypertension, and disease severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:555–561. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham G., Devine P.C. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. 2005;29:69–76. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deprest J., Brady P., Nicolaides K. Prenatal management of the fetus with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the era of the TOTAL trial. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;19:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snoek K.G., Reiss I.K.M., Greenough A. Standardized postnatal management of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: the CDH EURO consortium consensus—2015 update. Neonatology. 2016;110:66–74. doi: 10.1159/000444210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putnam L.R., Tsao K., Morini F. Evaluation of variability in inhaled nitric oxide use and pulmonary hypertension in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:1188–1194. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snoek K.G., Capolupo I., van Rosmalen J. Conventional Mechanical ventilation versus high-frequency oscillatory ventilation for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a randomized clinical trial (The VICI-trial) Ann Surg. 2016;263:867–874. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kays D.W. ECMO in CDH: is there a role? Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017;26:166–170. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishay M., Giacomello L., Retrosi G. Decreased cerebral oxygen saturation during thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia and esophageal atresia in infants. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver K.L., Baerg J.E., Okawada M. A multi-institutional review of thoracoscopic congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2016;26:825–830. doi: 10.1089/lap.2016.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansdale N., Alam S., Losty P.D., Jesudason E.C. Neonatal endosurgical congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2010;252:20–26. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dca0e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dassinger M.S., Copeland D.R., Gossett J., Little D.C., Jackson R.J., Smith S.D. Early repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallon S.C., Cass D.L., Olutoye O.O. Repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): does early repair improve patient survival? J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1172–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Partridge E.A., Peranteau W.H., Rintoul N.E. Timing of repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in patients supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koziarkiewicz M., Taczalska A., Piaseczna-Piotrowska A. Long-term follow-up of children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia—observations from a single institution. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2014;24:500–507. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1357751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]