Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Discuss the role of focused transthoracic echocardiography when assessing critically unwell obstetric patients.

-

•

Describe the echocardiographic findings of life-threatening emergencies.

-

•

Explain the need for robust governance processes when using focused transthoracic echocardiography in the clinical setting.

Key points.

-

•

Delayed recognition of the sick obstetric patient contributes to maternal morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Identification of an acutely unwell pregnant or recently pregnant patient requires a careful evaluation of routine observations and basic investigations.

-

•

Focused transthoracic echocardiography provides a rapid, non-invasive assessment of the cardiovascular system.

-

•

Focused transthoracic echocardiography may help differentiate non-specific, life-threatening signs or symptoms in the obstetric patient such as hypotension or dyspnoea.

-

•

Formal training in focused transthoracic echocardiography must be reinforced by ongoing maintenance of skills.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography is increasingly used in the perioperative setting to aid the management of critically unwell patients, by providing real time structural and physiological cardiovascular information.1 It is also referred to as goal-directed echocardiography.2, 3 It is a point-of-care, non-invasive tool used at the patient's bedside. When using an abbreviated scanning protocol, focused transthoracic echocardiography can be used to rapidly assess the sick pregnant patient and guide treatment. This article aims to review the application of focused transthoracic echocardiography in obstetrics.

Background

Maternal cardiovascular disease remains the largest single cause of maternal death, but sepsis, venous thromboembolism, amniotic fluid embolism and haemorrhage are significant causes of morbidity and mortality.4 Delayed recognition of the sick obstetric patient has been cited as a contributory factor in the recent Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths report.5

When assessing the haemodynamic status of an acutely unwell pregnant or recently pregnant patient, the cardiovascular changes of pregnancy must be considered, along with the patient's ability to compensate during a pathological process. Identification of an acutely unwell obstetric patient starts with a basic approach (i.e. a thorough clinical examination and careful evaluation of routine observations: heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, and temperature) using a structured approach such as airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure (ABCDE). Any non-reassuring features should prompt basic investigations such as haemoglobin measurement, arterial blood gas analysis, chest X-ray (CXR), or electrocardiogram (ECG). It is this basic approach that should alert the practitioner to the patient's clinical state. The role of focused transthoracic echocardiography is to help solve the diagnostic challenge.6, 7

Physiological changes during pregnancy

Maternal hormonal changes during pregnancy cause a reduction in systemic vascular resistance and a resulting increase in cardiac output in order to maintain arterial BP.8 In general, this leads to an increase in stroke volume and results in an increase in left ventricular muscle mass, but the extent of cardiac changes varies from person to person. Some healthy pregnant women may have a lower than expected cardiac output measured on echocardiography; mild diastolic dysfunction is present in some asymptomatic pregnant women who are otherwise healthy.9 The heart is physically displaced within the thorax later in pregnancy because of an upwards-shifted diaphragm. Mild tricuspid and mitral regurgitation are seen in normal pregnancy, while pericardial effusions are not uncommon in term pregnant women.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography

Focused transthoracic echocardiography is an abbreviated form of a comprehensive echocardiographic examination, delivered at the point of care and requiring a more basic level of competency. It is intended to supplement the physical examination, basic investigations, and aid diagnosis of significant pathology.1, 10 The technique has been described previously in the context of critical care.11 The aim is to obtain standard echocardiographic views (parasternal, apical, and subcostal) in order to recognise gross abnormalities. These may include spontaneous cardiac movement in pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest, significant pericardial effusion, significantly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, gross right heart dilation suggestive of pulmonary embolus, and markedly low left ventricular end-diastolic volumes suggestive of hypovolaemia. Any patient found to have gross abnormalities should be referred, once stable, for a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative echocardiography examination. A focused assessment that does not reveal such abnormalities does not equate to a normal echocardiography examination.

Focused examinations follow a protocol primarily using the 2D modality, to ask specific clinical questions (Table 1). A systematic approach is necessary, but obtaining images in all basic viewing planes is not essential, especially when rapid diagnosis and management is needed, for example in the peri-arrest setting. Some views are preferable when looking for specific pathology. The parasternal short axis view is particularly useful for assessing volume status in terms of collapsibility of the left ventricle or identifying regional wall motion abnormalities, as this is the only view where all three coronary artery territories are seen. Conversely, the apical four-chamber view enables direct comparison of the left and right ventricles to help identify signs of right heart failure.

Table 1.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography assessment.10

| Question being asked | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Is there ventricular activity? | Confirmation of cardiac arrest |

| Are the ventricles grossly dilated? | Myocardial insufficiency |

| Is there adequate ventricular function? | |

| Are there regional wall motion abnormalities? | Myocardial ischaemia |

| Is the right ventricle dilated? | Pulmonary embolism |

| Is the IVC fixed and dilated? | |

| Is the left ventricle underfilled? | Hypovolaemia |

| Is the IVC collapsing on inspiration? | |

| Is there a pericardial effusion? | Pericardial effusion |

| Are there signs of tamponade? |

IVC, inferior vena cava.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography in the obstetric patient

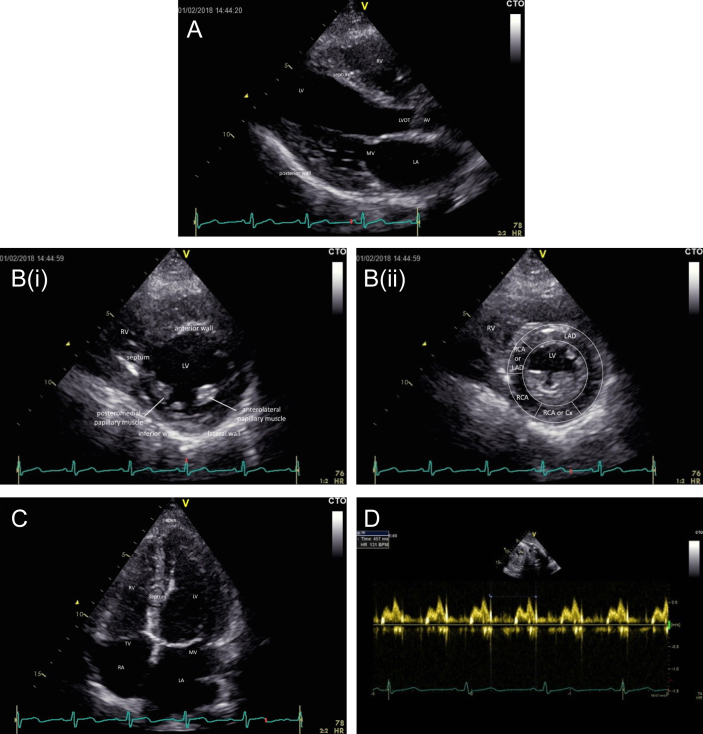

Pregnant patients are generally accepting of ultrasound examinations as the technique is non-invasive and is frequently performed as part of their obstetric management.12 The anatomical changes in pregnancy actually facilitate echocardiography examination. The patient should be placed in the left lateral position, avoiding aortocaval compression associated with lying supine. The subcostal approach, which requires the supine position, should only be used to assess post-partum women. The upward shift of the heart, closer to the thoracic wall in late pregnancy, improves visualisation via the parasternal and apical windows, although the apical view can sometimes be compromised in those patients with larger breasts. The structural echocardiographic findings are shown in Table 2, in addition to assessment of left and right ventricular size and function in each viewing plane. Examples of views obtained in a healthy pregnant patient are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Qualitative echocardiographic findings of a ROSE scan (adapted from Dennis and Stenson).13

| Echocardiography image plane | Key qualitative findings sought |

|---|---|

| Parasternal long axis | Presence of a large pericardial effusion, presence of an intracardiac mass, aortic dissection |

| Parasternal short axis | Presence of regional wall motion abnormalities, presence of a large pericardial effusion, presence of an intracardiac mass, position of the interventricular septum, markedly reduced contraction of the left ventricle |

| Apical four-chamber | Presence of increased right ventricular size compared with left ventricular size, presence of regional wall motion abnormalities, presence of a large pericardial effusion, presence of an intracardiac mass, position of interventricular septum, position of interatrial septum |

| Subcostal four-chamber | Impractical in the presence of a gravid uterus, can be considered post-partum. Presence of large pericardial effusion, presence of an intracardiac mass |

| IVC | Impractical in the presence of a gravid uterus, can be considered post-partum. Size and collapsibility of IVC |

IVC, inferior vena cava.

Fig 1.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography assessment in a healthy pregnant patient, 33 weeks gestation, arterial BP 120/82 mm Hg. (A) Parasternal long axis view. Qualitative observations: no large pericardial effusion; no gross abnormality of mitral valve movement; movement of posterior wall and interventricular septum within normal limits. (B) Parasternal short axis view (i) end-diastolic image, (ii) end-systolic image illustrating coronary artery territories. Qualitative observations: end-diastolic area and end-systolic area within normal limits, normal contraction; reduced ejection fraction heart failure unlikely; normal relationship between left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV) (i.e. no bulging of interventricular septum into LV suggesting raised RV volume or pressure); no large pericardial effusion. (C) Apical four-chamber view. Qualitative observations: normal relationship between LV and RV (i.e. the LV is larger than the RV); no pericardial effusion. (D) Abdominal ultrasound scan for fetal HR. Quantitative measurements: fetal HR is 131 beats min−1. Cx, circumflex; LAD, left anterior descending; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; MV, mitral valve; RCA, right coronary artery; TV, tricuspid valve.

The Rapid Obstetric Screening Echocardiography (ROSE) scan has been developed specifically for the obstetric patient and takes into consideration the unique physiological and anatomical changes that occur during pregnancy.12 The ROSE protocol includes qualitative and quantitative measurements that incorporate the basic views of a focused scan but extend to more advanced techniques including cardiac output estimation using Doppler assessment in the apical five-chamber view and an evaluation of diastolic function. The principles of the ROSE scan are:

-

(i)

Acceptable and applicable

-

(ii)

Bedside test at left hand side of the patient

-

(iii)

Comfortable and concise examination—parasternal views, apical views

-

(iv)

Diagnosis and response to therapy—contractility status and volume status

-

(v)

Embolism (air, blood, amniotic fluid)—right heart function and relative size

-

(vi)

Fetal HR assessment by appropriately trained personal. This requires an understanding of how to locate the fetal HR and differentiate from the maternal pulse. Obstetric anaesthetists should be able to interpret gross fetal HR abnormalities such as a significant bradycardia that requires immediate delivery.

Focused transthoracic echocardiography in obstetric practice

The obstetric patient may present with non-specific signs and symptoms, such as hypotension or dyspnoea that can generate diagnostic uncertainty. Focused echocardiography may help differentiate some of the life-threatening causes of dyspnoea such as pulmonary embolism (visualisation of thrombus or signs of right heart failure), acute pulmonary oedema, or peripartum cardiomyopathy (impaired ventricular function). Postpartum hypotension can be caused by a number of serious pathologies as summarised in Table 3.13

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of postpartum hypotension using the ROSE scan (adapted from Dennis and Stenson).13 *Sepsis without myocardial depression

| Obstetric haemorrhage | Myocardial infarction | Cardiac failure | Disease sepsis* | Pulmonary embolism | Aortic dissection | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical symptoms and signs | Hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, evidence of blood loss—decreasing haemoglobin concentration | Hypotension, chest pain, ischaemic ECG changes, arrhythmias | Hypotension, tachypnoea, tachycardia | Hypotension, fever, tachycardia | Hypotension, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnoea, ECG changes | Hypotension, chest pain, interscapular pain | Consider trauma; pericardial effusion with tamponade; tension pneumothorax |

| PLAX and PSAX end-diastolic diameter | Reduced LVEDD | Normal LVEDD | Increased LVEDD | Normal LVEDD | Increased RVEDD | ||

| A4C ventricular volumes | Reduced LV and RV volumes | Normal LV and RV volumes | Increased LV and RV volumes | Normal LV and RV volumes | Increased RV size compared with LV | ||

| A4C contractility | Normal or increased LV and RV contractility | Reduced LV contractility, RWMA | Reduced LV and RV contractility | Increased LV and RV contractility | Normal, reduced or increased RV function | ||

| Haemodynamic cause of hypotension | Reduced preload | Reduced contractility, arrhythmia | Reduced contractility | Vasodilatation | Right heart failure |

A4C, apical four-chamber view; LV, left ventricle; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; PLAX, parasternal long-axis; PSAX, parasternal short-axis; RV, right ventricle; RVEDD, right ventricular end-diastolic diameter; RWMA, regional wall motion abnormality.

Patients with pre-eclampsia can present with acute pulmonary oedema in the setting of hypertension and preserved ejection fraction heart failure which is an important diagnosis to make. Qualitative and basic quantitative measurements, such as assessment of diastolic function, are required to diagnose and treat this life-threatening complication of pre-eclampsia where left ventricular contractility may be normal (preserved) leading to the normal appearance of contractility in the parasternal short axis view. Assessing volume status in the sick patient with pre-eclampsia is often a challenge. The cause of oliguria in these patients is multifactorial and usually requires no intervention in the context of normal renal and respiratory function. However, a focused transthoracic echocardiography assessment of intravascular volume status and diastolic function can provide useful information and guide therapeutic management.

Although evidence is lacking of improved outcomes in obstetric patients where focused transthoracic echocardiography has been used, there have been several published reports describing patient management being transformed by the significant findings obtained from focussed transthoracic echocardiography assessment (Table 4 and Appendix A).13, 14, 15

Table 4.

Summary of focused transthoracic echocardiography findings in case studies.13, 14, 15 Further details of case studies 1–3 are provided in Appendix A

| Case study | Presenting signs and symptoms | Working diagnosis | Focused echocardiography findings | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tachycardia, hypotension, fever | Hypovolaemia, sepsis | Well filled left ventricle, poor contractility | Left ventricular failure |

| 2 | Chest pain, dyspnoea, followed by tachycardia, hypertension, hypoxia | Gastroenteritis, sepsis | Severely impaired left ventricle and abnormal aorta | Type A aortic dissection diagnosed with transoesophageal echocardiography |

| 3 | Dyspnoea, tachypnoea, tachycardia | Pulmonary embolism | No evidence of ultrasound features suggestive of pulmonary embolism | Salicylate poisoning |

Appendix A: case studies.

Case study 1: postpartum hypotension13

A previously fit and well 29-yr-old primiparous woman presented with an antepartum haemorrhage at 35 weeks gestation. A caesarean section was performed under spinal anaesthesia. The procedure and immediate postoperative phase were uncomplicated.

Six hours after the operation, the patient became unwell exhibiting signs of hypotension, tachycardia, and a raised temperature. Fluid resuscitation was commenced along with i.v. antibiotics and vasopressors. The haemoglobin was measured at 122 g dl−1. These interventions had minimal impact though, as the patient remained hypotensive and the cause of this was unclear.

A focused transthoracic echocardiography assessment was performed by the anaesthetist at the patient's bedside to make some immediate qualitative assessments of cardiac function. The parasternal short-axis view at the mid-papillary level demonstrated a well filled left ventricle with poor contractility, showing an estimated ejection fraction of <10%, suggesting a diagnosis of hypotension secondary to left ventricular systolic failure.

A pulmonary embolus was unlikely, as no thrombus was identified in the right ventricle or pulmonary arteries, and the right ventricular size was not increased. Similarly, coronary artery disease was not a likely cause of the patient's symptoms as she did not complain of chest pain, and there were no ECG changes or gross regional wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography assessment.

The echocardiographic features suggesting a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy and not hypovolaemia, thrombus, or coronary artery disease prompted an amendment to the management plan from fluid resuscitation to diuresis and inotropic support. The patient demonstrated immediate improvement with this therapy and made a good recovery. A diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy was subsequently made.

Case study 2: type A aortic dissection14

A 34-year old pregnant woman was admitted to hospital with chest pain and vomiting. She was at 39 weeks gestation and had previously had a planned caesarean section for breech presentation complicated by a primary post-partum haemorrhage needing a blood transfusion.

The pain was described as sharp affecting the chest, upper abdomen, and back. She had vomited a number of times and reported one episode of coffee-ground vomiting. She was haemodynamically stable, and both ECG and CXR were reported as normal. She was considered to have gastroenteritis so was treated with i.v. fluids, an H2 receptor antagonist, and kept nil by mouth.

Although the patient's observations and fetal assessment remained reassuring at first, the pain and vomiting persisted. After 3 h, her condition deteriorated. She was drowsy and noted to have a tachycardia, hypertension, and hypoxia. A maternal blood gas revealed a metabolic acidosis and confirmed hypoxia. Furthermore, there were signs of fetal distress on the cardiotocograph. A repeat CXR demonstrated lower and mid zone diffuse bilateral shadowing.

An emergency caesarean section was performed under general anaesthesia for severe maternal sepsis. Pink frothy secretions were aspirated from the tracheal tube and high inspired oxygen concentrations were required. The infant was initially delivered in a poor condition and transferred to the neonatal unit but made a good recovery. Maternal arterial BP remained stable throughout the operation and the tachycardia improved with fluid boluses. Invasive lines were inserted and the patient was transferred to the ICU for ongoing management of suspected sepsis.

During insertion of a radial arterial line, it was noted that the arterial BP readings were lower in the right arm than the left. Focused transthoracic echocardiography performed at the bedside by the intensive care registrar identified a severely impaired left ventricle and an abnormal aorta. This was confirmed by a more detailed assessment with transoesophageal echocardiography where aortic root dilatation was noted, in addition to moderate to severe aortic valve regurgitation and an intimal dissection flap in the ascending aorta.

A lifesaving emergency aortic root replacement was performed 4 h after the caesarean section. The patient recovered well after a prolonged intensive care stay.

Case study 3: pulmonary embolism15

A young woman was transferred to an emergency department for further evaluation of symptoms suggestive of pulmonary embolism. She was 20 yr of age, parity one, and 22 weeks pregnant. She had presented with a 2-day history of shortness of breath, tachypnoea, and tachycardia. The ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia. She had no past history or family history of thrombophilia.

An initial CT scan was inconclusive because of poor imaging. A bedside transthoracic echocardiography was performed in the emergency department to evaluate for ultrasound features suggestive of pulmonary embolism. There was no evidence of a pericardial effusion or regional wall motion abnormalities. The inferior vena cava showed normal respiratory variation and was not dilated. There was no mobile thrombus in the right heart or pulmonary artery, and no signs indicating right ventricular dilation with no evidence of flattening or bowing of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle. The specificity of ultrasound evidence of pulmonary embolism was high but sensitivity was low.15 Thus, a repeat CT scan was performed, this time with good images, ruling out pulmonary embolism. Upon further questioning, the patient confirmed taking regular aspirin for toothache. Salicylate level was increased and appropriate treatment administered.

This case illustrates the usefulness of performing a focused transthoracic assessment to obtain valuable information that can further direct management.

Governance

To perform focused transthoracic echocardiography safely, practitioners must undertake supervised training and regularly practice their skills. National guidance is available in the UK and Australia.2, 3, 16 The technical skills of image acquisition can be achieved relatively easily by practice on healthy volunteers or simulators. It is the interpretative skills that require experience and an understanding of pathological conditions.10 Those learning focused transthoracic echocardiography must be mindful of common misinterpretations that may lead to incorrect management decisions.17 Formal training programs usually consist of theoretical knowledge and completion of a logbook with supervised studies, after which certification or accreditation is provided. An electronic record should be stored where possible and a written report outlining the major findings, recommendations, and operator details recorded in the notes. Only practitioners who have completed the relevant training should issue formal reports from the information obtained.2, 10

The availability of training opportunities in obstetric patients is more of a challenge. Access to a transthoracic ultrasound probe may not be readily available and gaining skills in interpreting images of the acutely unwell obstetric patient is less accessible than in a critical care unit. Once competence has been achieved, these skills must be maintained with regular practice, thus focused echocardiography should not be considered an ad hoc skill but requires dedication and a commitment to ongoing training. With the appropriate consent, patients presenting for elective procedures may provide valuable opportunities to develop and translate these skills into routine practice. An educational program that supports the ongoing development and maintenance of these skills has been described, highlighting the need for practitioners to perform a minimum of 50 scans per year and attendance at departmental transthoracic echocardiography clinical case quality assurance meetings in order to maintain competence.3 Obstetric anaesthetists wishing to become competent in focused transthoracic echocardiography may find their best avenue for developing and maintaining these skills is through their local ICU where focused echocardiography is becoming widely accepted practice.11, 16, 17

Summary

A focused transthoracic echocardiography assessment can provide crucial information to assist diagnosis and enable timely management of critically unwell obstetric patients. Anaesthetists wishing to develop this advanced skill must complete a formal training program and be supported in maintaining competence in these skills through their employing organisation.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Siân Griffiths BSc (Hons) FRCA LLM DipCRCM is a consultant anaesthetist at Guy's & St. Thomas's NHS Foundation Trust, London. She is a member of the Obstetric Association of Anaesthetists and has clinical and research interests in the application of focused echocardiography in obstetric anaesthesia.

Greg Waight BSc (Hons) FRCA is a higher specialty trainee in anaesthesia at Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust, Kent, UK.

Alicia Dennis PhD MIPH PGDipEcho FANZCA is an associate professor at the University of Melbourne, a staff specialist anaesthetist, and the director of anaesthesia research at the Royal Women's Hospital, Parkville, Australia. She obtained her PhD in 2010 and NHMRC fellowship in 2015. In 2017, she completed a master's degree in International Public Health. Her research interests include cardiac function in women with pre-eclampsia, obstetric critical illness, the role of echocardiography in critical illness, and maternal mortality in low middle income countries.

Matrix codes: 1A01, 2B06, 3B00

Appendix A.

References

- 1.Barber R.L., Fletcher S.N. A review of echocardiography in anaesthetic and peri-operative practice. Part 1: impact and utility. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:764–776. doi: 10.1111/anae.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PS46 guidelines on training and practice of perioperative cardiac ultrasound in adults. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; 2014. http://www.anzca.edu.au/documents/ps46-2014-guidelines-on-training-and-practice-of-p.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis A. Goal-directed transthoracic echocardiography – a translational education program. In: Riley R., editor. vols. 85–91. 2015. (Australasian anaesthesia. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of anaesthetists). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M., Nair M., Tuffnell D., Shakespeare J., Kenyon S., Kurinczuk J.J., on behalf of MBRRACE-UK . 2013–2015. Saving lives, improving mothers' care – lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential Enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity.https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight M., Kenyon S., Brocklehurst P., Neilson J., Shakespeare J., Kurinczuk J.J., on behalf of MBRRACE-UK . 2009–2012. Saving lives, improving mothers' care – lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential Enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity.https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennis A.T. The bench is the bedside – the role of transthoracic echocardiography in translating pregnancy research into clinical practice. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1207–1210. doi: 10.1111/anae.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucas D.N., Elton C.D. Through a glass darkly – ultrasound imaging in obstetric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:617–622. doi: 10.1111/anae.13466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedson R., Riccoboni A. Physiology of pregnancy: clinical anaesthetic implications. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis A.T., Castro J., Carr C., Simmons S., Permezel M., Royse C. Haemodynamics in women with untreated pre-eclampsia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:1105–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma V., Fletcher S.N. A review of echocardiography in anaesthetic and peri-operative practice. Part 2: training and accreditation. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:919–927. doi: 10.1111/anae.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson S., Mackay A. Ultrasound in critical care. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2012;12:190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis A.T. Transthoracic echocardiography in obstetric anaesthesia and obstetric critical illness. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2011;20:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis A., Stenson A. The use of transthoracic echocardiography in postpartum hypotension. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:1033–1037. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826cde5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston C., Schroeder F., Fletcher S.N., Bigham C., Wendler R. Type A aortic dissection in pregnancy. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel A., Nickels C., Flach E., De Portu G., Ganti L. The use of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of patients presenting with signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:312632. doi: 10.1155/2013/312632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joint working party of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland, The Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Intensive Care Society . The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland, The Royal College of Anaesthetists, and The Intensive Care Society; London: 2010. Ultrasound in anaesthesia and intensive care: a guide to training. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanco P., Volpicelli G. Common pitfalls in point-of-care ultrasound: a practical guide for emergency and critical care physicians. Crit Ultrasound J. 2016;8:15. doi: 10.1186/s13089-016-0052-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]