Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Describe the initial management of a child presenting with burn injury.

-

•

Understand the importance of accurate estimation of burns as a percentage of total body surface area and subsequent fluid resuscitation.

-

•

Discuss the anaesthetic management of a child with severe burns.

-

•

Explain the benefits of providing optimal sedation and analgesia for children having burns procedures outside the operating theatre, and the drugs commonly used.

Key points.

-

•

Burns in children are common; the anaesthetist plays a key role in their management, including resuscitation, perioperative care and pain control.

-

•

Estimating burns injury remains problematic and inaccurate; the use of new technology, such as the Mersey App, can help improve accuracy even for medical professionals with little experience of burns.

-

•

Fluid resuscitation is a key element in the treatment of burns.

-

•

‘Fluid creep’ is the term used to describe over-resuscitation with fluids leading to complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, compartment syndrome and cerebral oedema.

-

•

Optimising procedural sedation and analgesia in the child will help improve experience and reduce anxiety.

Burns injuries in children are common. They are the fifth most common presentation of non-fatal childhood injuries worldwide (WHO).1 An estimated 37,700 children per year attend emergency departments in England and Wales. Approximately 6,600 (17.5% of all trauma cases) are admitted for burns management.2 The majority of admissions result from scalds, followed by contact and flame burns. Less common injuries in children include electrical, chemical and radiation burns.

The incidence of burns is higher in children than in adults. Most paediatric burns are small and can be managed in non-specialist centres. However, there is a wide spectrum of injury pattern and severity. Babies, in particular, can be more vulnerable because of their inability to move away from the causative agent. Toddlers often start reaching up for cups on tables that may contain hot drinks. The impact of heat on the skin varies with age. Infants have thinner and less heat-resistant skin compared with older children and adults. Hence, the same exposure can lead to more significant burns over a shorter period of time.

Burns cause thermal injury to the skin, which in turn compromises its protective functions. By doing so, this effective barrier is lost and complications, such as hypothermia and infection, can occur. The importance of the integrity of the skin means that all but minor burns must be managed by treating the injury promptly and managing the sequelae.

Burns have a multifaceted impact on patients. Both acute and long-term treatments can lead to lengthy stays in a hospital. If transferred to a specialist burns unit, this may be far from home, friends and family. The acute and background pain, multiple procedures and physical changes that the children experience can lead to a significant psychological impact on them and their families.

The anaesthetist has an important role in the management of a child with a burn injury. As an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, the roles of an anaesthetist include initial resuscitation, perioperative care, procedural sedation and pain management. Further details of paediatric burns care are available in the BJA Education article ‘Burns in children’.3 This article aims to give an updated perspective on burns care in children.

Initial management

Children with burns may present to any hospital, not just a tertiary centre, and therefore, it is essential that practitioners are able to make an initial assessment of the burn and initiate resuscitation.

The initial approach to the child should follow Advanced Paediatric Life Support principles, with an ‘airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure’ (ABCDE) approach, and vigilance for other injuries in addition to the burn. Anaesthetists will be involved at the initial management stages of seriously burned children to provide airway assessment and management, i.v. access, sedation/analgesia and transfer.

It is important to have an understanding of the mechanism of injury to guide initial management. Burns sustained in an enclosed fire will be associated with smoke inhalation, and resultant airway injury will be compounded by soot, noxious substances and hypoxia. Airway oedema will progress rapidly; therefore, early tracheal intubation is mandatory in severe cases. Injuries caused by scalds may be more severe in children who are not independently mobile (e.g. infants or those with physical disabilities).

Non-accidental injury must always be considered: inconsistencies in the history and pattern of burn, or a delay in presentation are factors that will increase suspicion. Any concerns should be raised with the local safeguarding team.

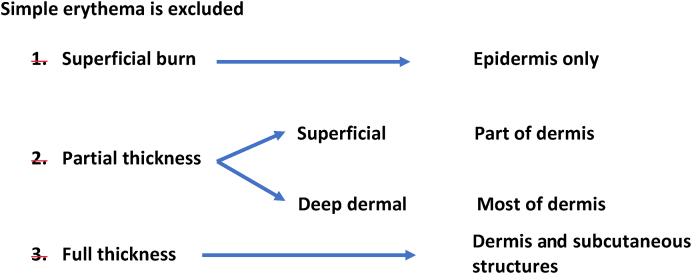

Assessment of the size and depth of the burn forms part of the secondary survey, and guides both fluid resuscitation and the location of ongoing care, so accuracy is imperative. The depth of the burn is determined by identifying the destruction to the layers of the skin—the epidermis and the dermis (Fig 1). Burns range from superficial, partial thickness and full thickness. This assessment helps establish the likely timescale for healing.

Fig. 1.

Burn depth and extent of dermal injury.

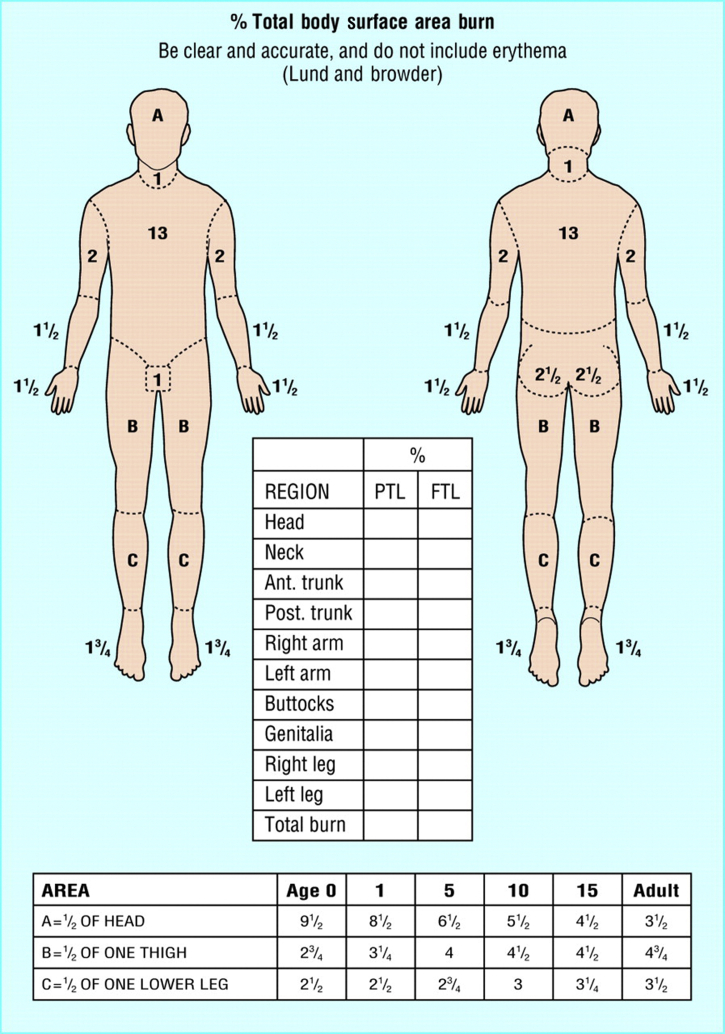

The total body surface area (TBSA) of a burn was traditionally assessed using Lund and Browder burns chart that denotes the percentage of body surface and changes with age of the child (Fig 2). An alternative rule is that the patient's palm and fingers represent 1% of the body surface.

Fig. 2.

Lund and Browder chart.

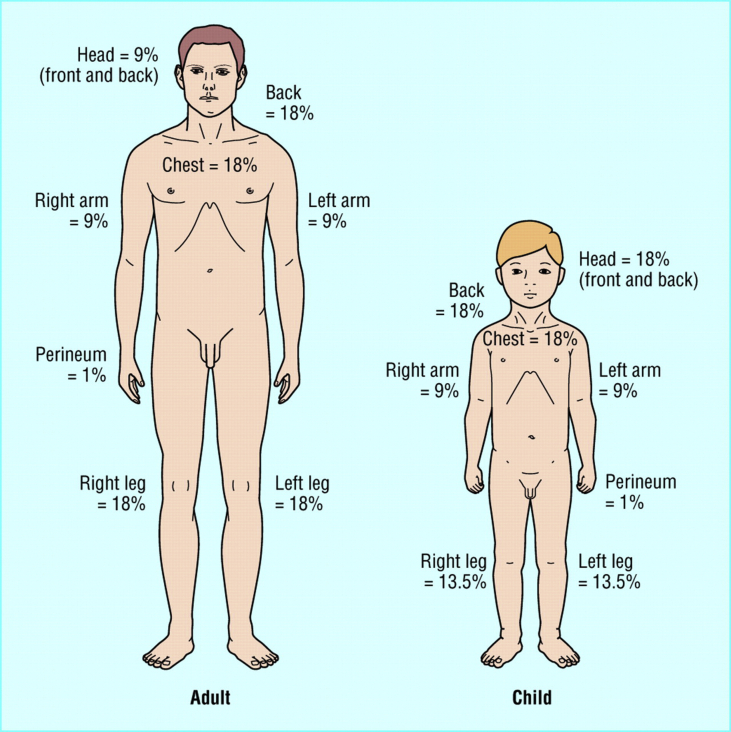

The ‘rule of nines’ is used for a rapid field estimate in patients to help determine whether they need to be transferred to a specialist centre (Fig 3). Again, this is adjusted for paediatric burns. Despite these various methods to estimate TBSA, it remains a problem that the size of the burn is often overestimated, particularly in children.4

Fig. 3.

Rule of nines' for adults and children.

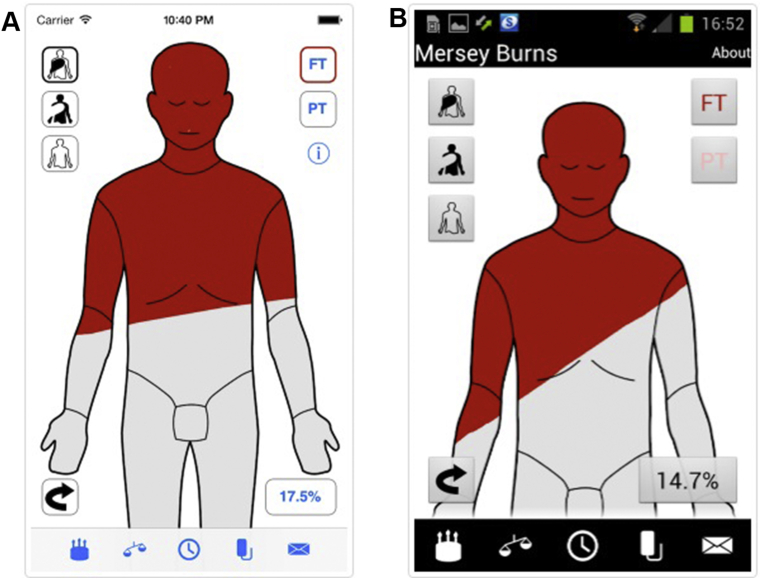

Smartphone technology can be used to help estimate the size of a burn: the Mersey Burns app (Fig 4) allows a user to input the age and weight of the patient, and colour in the areas of full- and partial-thickness burns. Based on this, it formulates the burn percentage and performs fluid resuscitation calculations.5 This free clinical tool is available on multiple platforms, including Apple App Store, Android and Google Play. (Note: the authors of this article have no affiliation to the Mersey Burns App.)

Fig. 4.

Example of the Mersey Burns App.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has produced an innovation briefing for the app, and, although the evidence at present is limited, studies using clinical simulations have suggested that the app might help in producing faster and more accurate fluid calculations. Its use in acute care settings, such as the emergency department, without the need for a paper chart and calculator, has obvious benefits: if it can reduce the assessment time and facilitate early management by non-burns specialists, then it may be a useful tool for many acute clinicians.6

Once the initial assessment and resuscitation process has started, it is important to consider whether the child should be transferred to a specialist centre. The transfer of children to a specialist burns unit is based on the following criteria: burn >5% TBSA; any burn involving the face, hands, feet, perineum or over a joint; circumferential burns; burns associated with inhalational injury; and electrical and chemical burns (Box 1).

Box 1. Criteria for transferring a child to a specialist burns unit.

-

•

Burn >5% body surface area

-

•

Any burn involving the face, hands, feet, perineum, or over a joint

-

•

Circumferential burns

-

•

Burn associated with another injury or with inhalational injury

-

•

Suspected non-accidental injury

-

•

Electrical burns

-

•

Chemical burns

Alt-text: Box 1

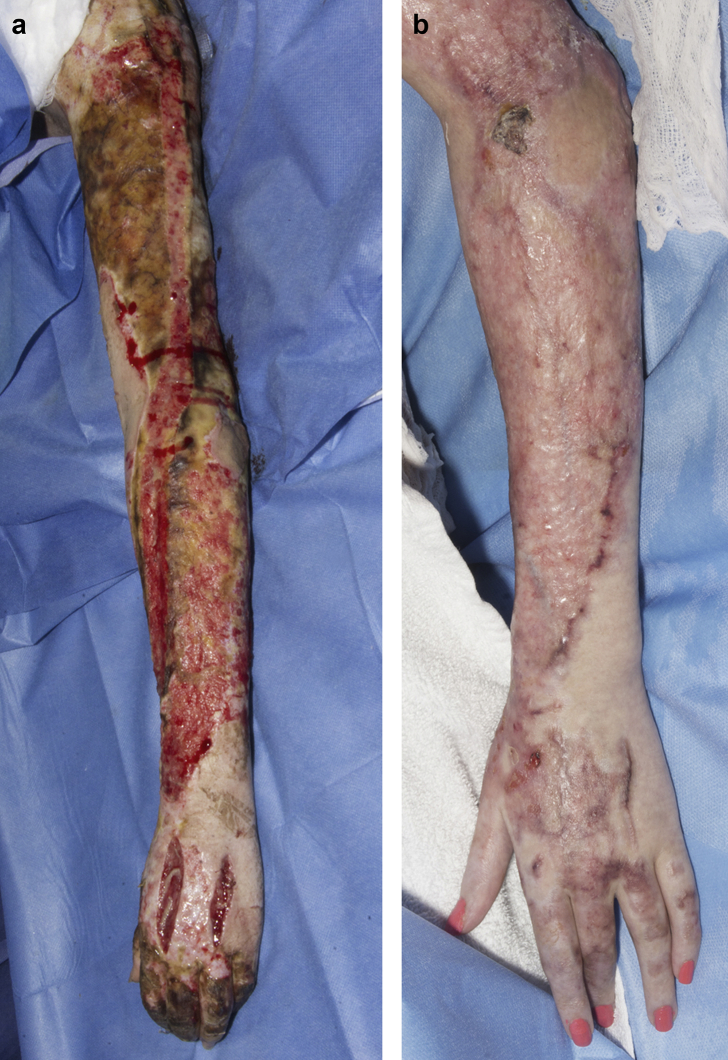

In the unfortunate event of a child suffering severe burns, consideration should be taken as to the suitability of transfer to a burns centre in the first place. A balance between the end-of-life needs of a child and family alongside the chance of recovery if transferred to a centre of expertise should be sought. With that being said, it is important to note that more patients with severe burns are surviving and discussion should be had with the specialist centre. One major reason why more severely injured patients are surviving is because of advances in burns management. These advances include improved resuscitation, surgical expertise and reduced blood loss, early antibiotic therapy (including topical) and critical care management. Nevertheless, the impact of severe burns can be debilitating both physically and mentally, impacting quality of life. Therefore, it is imperative that there is continued improvement in treatment and rehabilitation. Children, with even very severe burns, often do unexpectedly well long term (Fig. 5a and 5b).

Fig. 5.

This is the arm of a 15 year old shortly following a full thickness scald injury to 50% of their body (Fig 5a), and then three months after (Fig 5b). Further rehabilitation since this time has meant that the child is now back at school and doing well (written permission given from both child and parent).

The Baux score is a popular scoring system used in burns.7 It first came into prominence in the 1960s and determined predicted mortality by adding the age of the patient to the percentage of burns inflicted (age+% TBSA). A total score of 100 would represent a predicted mortality of 100%. This can now be challenged, given the improved treatment and management of burns. Some large-scale studies suggest that 100% predicted mortality is at a score closer to 160 rather than 100.8 This would suggest that all children, even those with the severest of injuries, could survive.

Many institutes now use a modified Baux score, in which they take into consideration inhalational injury. When an inhalational injury is present, 17% is added to the final score. It is argued that this provides a more precise prediction of mortality.9

Fluids

Fluid management in paediatric burns remains a subject of discussion. In general, loss of circulating volume after burns injury is proportional to the severity of the burns. For minor burns, oral hydration may be acceptable. Any paediatric burn with greater than 10% TBSA requires i.v. fluid replacement.

After burns injury, increased vascular permeability leads to significant fluid shifts resulting in intravascular volume depletion. Patients often have reduced vascular resistance and can experience systemic inflammatory response syndrome, leading to an initial period of myocardial depression. In addition, in TBSA >25%, there is systemic oedema, which develops at 4 h and continues until 36 h after injury.

These changes reduce cardiac output and lead to hypoperfusion, and, in severe cases, circulatory shock. Early fluid resuscitation is essential. Delays in fluid resuscitation can increase risks of acute renal failure, multi-organ dysfunction, prolonged stay in a hospital, and mortality.10 This may occur because of difficult i.v. access. In such cases, the intra-osseous route should be rapidly established. In children presenting with circulatory shock, a bolus of crystalloid 20 ml kg−1 should be given.

Formal fluid resuscitation is a requirement for anyone with greater than 10% TBSA burns. Similar to adults, a formulaic approach, adapted based on physiological endpoints, is advocated. Paediatric-specific formulae are available. These incorporate physiological differences in the paediatric patient. The most commonly used formula is the Parkland formula, measured in millilitres.11 This is 3–4 ml kg−1×TBSA % burns over a 24 h period. Half the total is given over the first 8 h from the time of burn, and half over the following 16 h. A move towards more restrictive fluid regimens has seen the use of other formulas, such as the modified Brooke formula.12 This uses 2 ml kg−1×TBSA % burns over the same time period as the Parkland formula.

The ‘crystalloid vs colloid’ debate is a subject that generates a lot of interest. Many believe that the initial fluid of choice should be a balanced crystalloid. The increased capillary permeability during the first hours after injury, they argue, makes the use of colloids inappropriate.13 Hartmann's solution is a commonly used crystalloid and can provide a good profile to protect against electrolyte imbalance. Outside of the initial resuscitation phase, colloids, such as albumin or plasma, have been favoured by some. Several studies have suggested that albumin reduces fluid requirements during resuscitation.14 Nevertheless, strong evidence to support specific fluids in burns resuscitation is limited, at best, and the choice is often a subjective one.

In addition to resuscitation fluids, maintenance fluids should also be given to children. Adding glucose for those who are hypoglycaemic, or at risk of hypoglycaemia, is essential. It is imperative that clinicians use their expertise to justify ongoing fluid management and adjust infusions accordingly. Using the endpoints of resuscitation and hydration can help establish this. Commonly used clinical endpoints include sustained urine output, intact sensorium, normothermia, age-appropriate haemodynamics and minimal systemic acidosis (Box 2).15

Box 2. Clinical endpoints for volume resuscitation.

-

•

Intact sensorium

-

•

Normothermia

-

•

Age-appropriate haemodynamics

-

•

Sustained urine output

-

•

Minimal systemic acidosis, base deficit <2

Alt-text: Box 2

In recent years, the phenomenon of ‘fluid creep’ has been recognised, whereby patients receive significantly more fluids than calculated.16 Just as under-resuscitation can lead to complications, over-resuscitation with i.v. fluids can be detrimental too. Over-resuscitation may lead to complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ dysfunction, abdominal and limb compartment syndrome, and cerebral oedema.

Fluid creep may occur if volumes of drugs, such as antibiotics, and electrolyte replacements, such as magnesium, are not taken into consideration. Often, such medications are given diluted in volumes that are not insignificant, especially in smaller children. Furthermore, by chasing an unrealistic or excessive urine output without considering the full clinical picture, the risk of over-resuscitation will increase.

Intraoperative management

A patient with burns often requires multiple visits to the operating theatre. Common procedures include wound cleaning and debridement, dressing changes and skin grafting. In circumferential burns, escharotomies may be required to avoid neurovascular compromise and compartment syndrome. Depending on the extent of the injury, multiple position changes may be needed for surgeons to access all affected areas. Good communication with the surgical team and operating theatre staff is essential.

Physiological changes

Paediatric patients with burns have multiple physiological changes that must be taken into account in the perioperative period. It is important for the anaesthetist to gauge whether the initial resuscitation phase has given the patient a degree of stability. Vital signs, urine output, hydration status and use of inotropic agents will all help in determining this.

Burns injury leads to patients having a hypermetabolic and inflammatory response after the first 24 h. This can last for a significant period of time (up to 2 yrs has been suggested by some sources).17 Most commonly, the severity of the burns will correlate to the extent of this response. The release of catecholamines and other stress hormones leads to refractory tachycardia, increased cardiac output, raised oxygen consumption and a sharply raised basal energy expenditure. One should bear in mind that, on induction of anaesthesia in the severely unwell child, depletion of catecholamines may lead to cardiovascular collapse. Therefore, the meticulous use of chosen induction agent(s) is essential. In such instances, inotropic and vasoactive agents should be immediately available.

Airway

If the airway is not already secured, a difficult intubation should be considered, particularly in facial and inhalational injury. Airway oedema, especially in the first 48 h, should not be underestimated. The use of video-laryngoscopy in such cases has become common practice. Loss of the airway can be fatal. Equipment and personnel to perform an emergency tracheostomy should be present.

Temperature

Temperature control is vital in paediatric patients with burns. Burns compromise the integrity of the skin and can cause significant heat loss. Constant measurement of core temperature is essential in the operating theatre. Commonly rectal, oesophageal or bladder temperature probes are used.

The ambient temperature in the operating theatre is increased—35°C is not uncommon. This can be uncomfortable for the operating theatre staff over a period of time: cooling jackets for staff should be made available. Warmed fluids, warming mattress and blankets are also utilised. The latter may be of limited use when there are widespread burns that need exposing. Nevertheless, areas that surgeons are not immediately treating should remain covered.

Post-burn pyrexia in children is a complication that can occur 24–48 h after the time of injury. It is often unrelated to infection, and antibiotics should not be started unless there is sufficient evidence to suggest otherwise. Fever further increases the basal metabolic rate and energy expenditure. In severe cases, haemofiltration is required for temperature control.

Monitoring

Standard monitoring, including an oxygen saturation probe, ECG leads and BP cuffs, can be difficult to apply, and the anaesthetist needs to be both imaginative and pragmatic on how and where to apply these. An arterial catheter is beneficial for both BP monitoring and arterial gas sampling. In major burns cases, this is essential.

As fluid loss can be substantial, a urinary catheter and hourly measurement are important. Cardiac output monitoring is increasingly being used, in which significant fluid shifts are predicted. A number of cardiac output monitors are licensed for use in paediatrics. These include oesophageal Doppler and LiDCO.

Blood loss during surgical procedures requires close attention. Actual blood loss can be difficult to assess. One study suggested that 3–5% estimated blood loss may occur for every 1% TBSA burn excised.18 Blood requirement for a given procedure may be estimated using the following formula: 3×weight (kg)×% burn.19 Surgical techniques to help reduce blood loss include the use of tourniquets and adrenaline-soaked swabs, and subcutaneous injection of adrenaline pre-excision (1:100,000). Subeschar injection (clysis) of bupivacaine and adrenaline can also help reduce blood loss.20 Diluted in saline 0.9% or Hartmann's solution, bupivacaine (0.001%) and adrenaline (1:500,000) are administered into subeschar and donor areas.

Special circumstances

There may be a number of situations when an unwell child has additional support that needs to be continued during surgical procedures. Examples of this include renal replacement therapy (RRT) and high-frequency oscillation ventilation. For such patients, their degree of single or multiple organ dysfunction may be such that without the extra support trips to the operating theatre would simply not be viable. Because of the lack of familiarity with this, anaesthetists may understandably feel out of their depth.

Patients may develop acute renal failure in burns for a number of reasons. Examples include severe metabolic acidosis, fluid overload, and electrolyte imbalance. Commonly used continuous RRT in paediatrics includes continuous venovenous haemofiltration and continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration. This requires trained, dedicated staff to oversee in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). It would be expected that the same staff would continue to oversee this whilst in the operating theatre. This requires prior organisation and communication with the PICU team. The vascular catheter being used should be free of kinks and working with good flow rates. An arterial blood gas should be taken before transfer to ensure that a degree of stability is present.

High-frequency oscillation ventilation is used in respiratory failure where conventional ventilation has been unsuccessful. In such cases, if it was deemed absolutely necessary for patients to go to the operating theatre, then reverting back to conventional ventilation using the anaesthetic machine is likely to worsen their condition. Such patients often have ARDS, and meticulous care needs to be taken with their respiratory function. The PICU consultant will need to be available for the duration of the procedure to help guide oscillator settings and ongoing clinical management.

Infection risk

Infection is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in burn injuries. Burn wounds are typically sterile in the initial period, but they are then colonised by Gram-positive (within 48 h) and Gram-negative organisms (usually within a week).21 Colonisation does not necessarily indicate infection. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for open wounds may lead to flora being replaced by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

When acute infection is suspected, empirical antibiotics should be given. Besides wound infection, it is important to exclude other sources of infection, such as those from the respiratory and urinary tracts. Antibiotics should be continued during the perioperative phase.

Analgesia

Managing pain in patients with burn injury is essential but often challenging, because the pain can be influenced by a number of factors. These include the allocation, size and depth of the burn; surgical and non-surgical procedures; evolution of the burn wound; and physical activity. Pain can be both centrally and peripherally mediated. The dynamic and evolving nature of pain means that background, breakthrough, procedural and postoperative pain all need to be accounted for.

In the postoperative period, the use of simple analgesics and opioids provides the backbone for pain control. Regular paracetamol and morphine, as required, are commonly prescribed. Oral morphine or i.v. through continuous or PCA pumps is used. An alternative for those who are intolerant of morphine is oxycodone.22 It is preferable in patients exhibiting renal failure and it has superior bioavailability.

NSAIDs should be used with caution in those with severe burn injuries. Although they are effective analgesics that may reduce opioid requirements, the incidence of adverse effects (including renal toxicity, gastric ulceration and antiplatelet effects) may preclude their use in many cases. Other useful drugs include gabapentin, ketamine and α2 agonists (such as clonidine and dexmedetomidine).

Procedural sedation and analgesia

Burns care often requires repeated painful procedures that can be performed safely outside the operating theatre. Common examples include dressing changes, staples removal and showers. A multimodal approach is essential, incorporating pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and using hypnosis, guided imagery and play therapy.

It is important to manage background and procedural pain to ensure ongoing treatment compliance and minimising psychological distress. Various sedative and analgesic drugs have been used to perform such procedures. An ideal drug would provide a reliable targeted level of sedation, preserve airway tone, have minimal cardiovascular and respiratory effects, provide good analgesia and have rapid onset and offset. Unfortunately, there is no current agent that can provide all of these.

The commonly used drugs for procedural sedation and analgesia in burns include ketamine, propofol, benzodiazepines and opioids. Ketamine has been used extensively in burns care for over 40 yrs. Its strong analgesic properties along with its maintenance of airway reflexes and cardiorespiratory profile make it ideal for procedural sedation. Adverse effects include agitation, hallucinations and emergence symptoms. For this reason, a second agent, such as a benzodiazepine, is given in conjunction.

Recent attention has been given to the use of dexmedetomidine for both procedural sedation and as a sedative in PICU. Its combination of analgesia, sedation, rapid onset and offset, make it a useful drug to consider in the paediatric burn patient requiring painful procedures. The casual use of drugs, such as propofol and opioids, for procedural sedation and analgesia can lead to a number of adverse events, including an obtunded airway and cardiorespiratory compromise. This has provided an opportunity for alternative agents, such as dexmedetomidine, to be used.

Dexmedetomidine works as an agonist on α2 adrenergic receptors primarily in the locus coeruleus of the pons. It provides sedation paralleling natural sleep and has little direct effect on respiration. Its cardiovascular effects are biphasic. It can induce bradycardia and hypotension. At higher serum concentrations, it can induce hypertension by activation of vascular smooth muscle α2β receptors.

Dexmedetomidine use as a single agent is limited by its analgesic properties. Its use in combination with ketamine has proved successful in painful procedures.23 Together, they can provide analgesia, sedation, haemodynamic stability and amnesia. Dexmedetomidine for sedation, for example, for radiological imaging, has seen boluses of 0.5–2 μg kg−1 followed by infusions of 0.2–1 μg kg−1 h−1 used to good effect.24 An example of ketamine dosing for procedural sedation is an i.v. bolus of 100–300 μg kg−1 followed by an infusion at 0–5 μg kg−1 min−1. When used in combination, caution is required with bolus dosing and infusion rates. The increasing periprocedural and perioperative use of dexmedetomidine may help establish its place as a valuable alternative to the older drugs currently used.

Summary

The anaesthetist has a key role throughout the management of a paediatric patient with burns. Thankfully, the vast majority of children, even those with severe injuries, survive and eventually leave the hospital. It is up to us, as part of the multidisciplinary burns team, to ensure that children with burns are given the best possible chance of making a good recovery and optimising their quality of life after a burn injury. Neither of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Amrit Suman LLB FRCA is a clinical fellow at the Royal Manchester Children's Hospital. His interests include neonatal anaesthesia, ENT, burns management and anaesthesia in the developing world.

Jan Owen BMedSci (Hons) FRCA is a consultant in paediatric anaesthesia and co-lead for burns at the Royal Manchester Children's Hospital, a designated paediatric burns centre. Her other interests are neuroanaesthesia, anaesthesia for children undergoing proton and photon beam therapy, and burns care in the developing world. She is the lead for clinical governance for operating theatres and anaesthesia, a member of the Manchester Foundation Trust's clinical ethics committee, and has a postgraduate diploma in medical law and ethics.

Matrix codes: 1A01, 2B05, 3J03

References

- 1.World Health Organization Burns fact sheet 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/details/burns Available from:

- 2.Davies K., Johnson E., Hollen L. Incidence of medically attended burns across the UK. Inj Prev. 2019 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-0442881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenlon S., Siddarth N. Burns in children. BJA Educ. 2007;7:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan Q.E., Barzi F., Cheney L. Burn size estimation in children: still a problem. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes J., Duffy A., Hammett N. The Mersey Burns App: evolving a model of validation. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:637–641. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-203416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Mersey burns for calculating fluid resuscitation volume when managing burns 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mib58 Available from:

- 7.Baux S. AGEMP; Paris: 1961. Contribution à l’étude du traitement local des brûlures thermiques étendues. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts G., Lloyd M., Parker M. The Baux score is dead. Long live the Baux score: a 27-year retrospective cohort study of mortality at a regional burns service. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:251–256. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824052bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osler T., Glance L., Hosmer D. Simplified estimates of death after burn injuries: extending and updating the Baux Score. J Trauma. 2010;68:690–697. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c453b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrow R.E., Jeschke M.G., Herndon D.N. Early fluid resuscitation improves outcomes in severely burned children. Resuscitation. 2000;45:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter C.R., Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:874–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb14738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David G., Greenhalgh M.D. Management of burns. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2349–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1807442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guilabert P., Usua G., Martin N. Fluid resuscitation management in patients with burns: update. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:284–296. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navickis R.J., Greenhalgh D.G., Wilkes M.M. Albumin in burn shock resuscitation: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e268–e278. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanelli T., Stickles E. Anaesthesia for burn injuries. In: Davis M.D., Peter J., Cladis M.D., Franklyn P., editors. Smith’s anesthesia for infants and children. 9th Edn. Elsevier; London: 2019. p. 1013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers A.D., Karpelowsky J., Millar A.J.W. Fluid creep in major pediatric burns. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20:133–138. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herndon D., Tompkins R.G. Support of the metabolic response to burn injury. Lancet. 2004;363:1895–1902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Housinger T.A., Lang D., Warden G. A prospective study of blood loss with excision therapy in pediatric burn patients. J Trauma. 1993;34:262–263. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199302000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emerson B. Burns in children. In: James I., Walker I., editors. Core topics in paediatric anaesthesia. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2013. pp. 406–415. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rode H., Brink C., Bester K. A review of the peri-operative management of paediatric burns: identifying adverse events. S Afr Med J. 2016;106:1114–1119. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i11.10938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill P., Falder S. Early management of paediatric burn injuries. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;27:406–414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson P., Mustard L. The management of pain in the burns unit. Burns. 2009;35:921–936. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahmood M., Mason K.P. Dexmedetomidine: review, update, and future considerations of paediatric perioperative and periprocedural applications and limitations. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:171–182. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiera P., Mason M.D. Sedation trends in the 21st century: the transition to dexmedetomidine for radiological imaging studies. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]