Learning objectives.

By reading this article you should be able to:

-

•

Distinguish the difference between primary and secondary pain disorders in children

-

•

Explain the importance of focusing on function rather than on a specific diagnosis

-

•

Formulate a ‘3P’ multidisciplinary approach comprising pharmacological, physical/physiological and psychological strategies that maximise function and quality of life.

Key points.

-

•

All pain, whether acute or persistent, is biopsychosocial in its presentation and management.

-

•

Early introduction of biopsychosocial management principles is recommended to improve adherence to treatment and clinical outcomes.

-

•

There are complex pain syndromes that are unique to childhood and those where the clinical course can differ from that in adults.

-

•

Management is best approached with a 3P multidisciplinary framework comprising pharmacological, physical/physiological, and psychological strategies.

-

•

Good quality evidence for treatment packages for complex pain in children is frequently lacking. Guidance is often extrapolated from adult studies or based on expert opinion and clinical experience.

All pain is biopsychosocial in its presentation and management. Acute protective pain is proportional to anticipated tissue injury and responds to first-line treatment because biological, psychological, and social factors are favourable rather than unfavourable. These factors are positive moderators of pain responses, and clinicians do not need to actively address them collectively, so they receive less, if any, consideration. Most biomedical diagnostic or therapeutic algorithms carry the implication that identifying the cause will eliminate the pain. However, in complex pain, if a cause is not found and pain persists, the focus often sharply turns towards psychosocial moderators of pain responses with an emphasis on function rather than pain reduction. Rather than this sudden gear change, the preferred scenario is one where all pain, whether acute or complex, is managed within a biopsychosocial framework from the outset.

Ideally, this achieves several outcomes: (i) it gives children, parents, and clinicians an opportunity to recognise positive interactions and learn from them, (ii) if first- and second-line interventions are unsuccessful, then a greater emphasis on psychosocial pain moderators represents a gradual and natural progression, (iii) although the data from adult studies have yielded mixed results, there is emerging evidence, and substantial clinical experience, suggesting that pre-emptively addressing function in psychosocial domains improves the success rate of invasive interventions such as nerve blocks.1

Primary pain disorders: diagnostic challenge

Medicine is continually evolving; diagnostic criteria and treatment pathways are revised and adapted as new concepts and clinical evidence emerge. Add to this a growing and developing child whose symptom complex may also evolve over time, and there is obvious potential for equally competent clinicians to give differing diagnoses. This may lead to confusion, anger, and loss of trust for children and their carers. Not all pain syndromes have validated paediatric criteria and adult criteria may be an imperfect fit. Rather than say ‘you have ’, it may be more useful to say ‘you currently meet the criteria for , but that may change’, as this allows some latitude. This approach may be applied to pain presentations such as chronic widespread pain or juvenile fibromyalgia, which may represent a spectrum of symptom severity along which individual patients may move. For example, a young person presenting with a triad of low mood, musculoskeletal pain, and non-refreshing sleep could simultaneously meet the diagnostic criteria for benign joint hypermobility syndrome, juvenile fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome depending on how stringently the criteria for each condition are applied. In addition, a diagnostic label associated with a chronic illness is not always in a child or young person's best interests.2 It is more beneficial to make function the primary emphasis, while suggesting that a diagnostic label is of secondary importance, as this is likely to change as treatment progresses. The goal of this approach is to help the patient to view their symptoms as something over which they have some influence: in one multidisciplinary treatment programme, 16% of children believed they could be pain-free at the beginning of treatment; this increased to 92% at the end of treatment.3

Secondary pain disorders: pain recognition

Despite the prevalence of complex pain, recent evidence suggests that children and young people still experience significant but avoidable pain while in hospital.4 This was more pronounced for infants and adolescents, and for medical rather than surgical inpatients,5 who may more readily receive input from an acute pain service. Severe pain can be a feature of conditions themselves, such as in sickle cell disease (SCD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and cystic fibrosis, and those where it is also the medical interventions that are associated with intense pain, such as the treatment of cancer (e.g. mucositis, graft vs host disease), burns, and epidermolysis bullosa. Although rarer, there are also conditions, such as erythromelalgia, Fabry's disease, or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, that may present with neuropathic pain for the first time in childhood and that are qualitatively different from the common neuropathic pain conditions seen in adults. Children also develop chronic postsurgical pain in greater numbers than previously reported, with a median prevalence of 20% across studies.6

Neuroplastic pain, neuroplastic plan

Multidisciplinary approach

Complex pain is difficult to manage because of the widespread and pervading negative effects that it can have on physical function, quality of life, mood, sleep, family relationships, school attendance, and socialisation. The challenge for all concerned is the conceptual shift that an improvement in function precedes a reduction in pain intensity. This usually requires a ‘3P’ multidisciplinary approach (pharmacological, physical/physiological, and psychological) that targets both peripheral and central pain mechanisms. Such a framework also has utility in routine acute pain situations to optimise postoperative pain management. For example, in post-tonsillectomy pain, the use of regular simple analgesia (pharmacological), the use of cold, e.g. ice lollies (physical), and distraction, e.g. playing video games (psychological) illustrate how such an approach can provide effective acute pain management.

Central and peripheral sensitisation

Most complex pain, whether a primary or secondary pain disorder, will involve a combination of peripheral sensitisation/primary hyperalgesia, and central sensitisation/secondary hyperalgesia. This point is worth making, as targeting only central or peripheral mechanisms will be less likely to produce the desired outcome. Central sensitisation may occur early in secondary pain disorders as a normal adaptive response to prevent further tissue injury.

Pain and activity level

Pacing of activities means finding a level of activity that can be done every day and maintained. Avoiding a ‘boom and bust’ activity cycle pattern is key, e.g. overdoing it one day and then doing nothing for several days results in a functional decline over time. Finding an activity level that can be maintained for a week, and then increased by 10–15% each week thereafter, allows for a stepwise progress trajectory rather than a linear one. Emphasis should be made that any setbacks will then only mean dropping back one or two steps rather than to baseline.

Sensory desensitisation

Altered sensory function in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) or other neuropathic pain can manifest as allodynia and hyperalgesia. This leads to the avoidance of any movement that might lead to pain. This can progress to a scenario where smaller and smaller degrees of movement are associated with exponentially increasing pain and hyperaesthesia. When this happens, one cornerstone of management is the normalisation of sensory function by providing a greater range of ‘normal’ sensations for peripheral nerves to process. This involves the progressive application of different textures (rough/smooth), temperatures (warm/cool), and consistencies (wet/dry) to the affected area until sensation approximates that of unaffected areas.

Motivation and adherence

Designing a bespoke multidisciplinary treatment package is one thing; motivating children and young people to stick to it despite ongoing pain, and frustration with the absence of an immediate reward for their efforts, can be quite another. Adherence to multidisciplinary treatment plans can be as low as 47% for children with complex pain.7 One psychological determinant of treatment adherence in chronic conditions is whether a patient's locus of control is external or internal. An external locus of control means that a person views their condition and its management to be mediated by external factors (e.g. environment, parents, and clinicians) and therefore outside their direct control. An internal locus of control is the belief that symptoms can be controlled by one's own efforts and is associated with better healthcare outcomes.8 Strategies to improve adherence do not need to be advanced or the sole preserve of psychologists. For example, using simple metaphors grounded in a child's own experience is something that all team members can do to make complex concepts accessible and understandable.9

Treatment packages

Specific recommendations for the management of the following complex pain conditions in childhood will be discussed; SCD, CRPS, and centrally-mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS), as for each the emphasis is on a different facet of biopsychosocial management principles.

SCD

SCD is an inherited disorder that typically causes episodic pain presenting in childhood with a range of severity according to the genotype. The pain is caused by vaso-occlusion of sickle erythrocytes in various sites including musculoskeletal locations, internal viscera, and penis. Such episodes of ischaemic pain are acute and intense, with patients returning to baseline shortly after. During adolescence, the pain of SCD can become more chronic with bone pain prominent, chronic organ damage, and evolving neuropathic pain features.10 Stroke, acute chest syndrome, avascular necrosis, and leg ulcers are other causes of hospitalisation and pain in patients with SCD.

Pain management in SCD can be challenging. Patients with painful crises have commonly experienced delays in receiving analgesia, received suboptimal doses of analgesia, and have sometimes been labelled as drug-seeking if they continue to complain of poorly-controlled pain or state a preference for a specific opioid. In response to this area in need of quality improvement, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has developed a clinical guideline11 and a quality standard for the management of sickle cell acute painful episodes.12 Among the quality statements included in this standard are ‘a clinical assessment and appropriate analgesia within 30 min of presentation’ and ‘an assessment of pain relief every 30 min until satisfactory pain relief has been achieved and then at least every 4 hours’( see Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4).

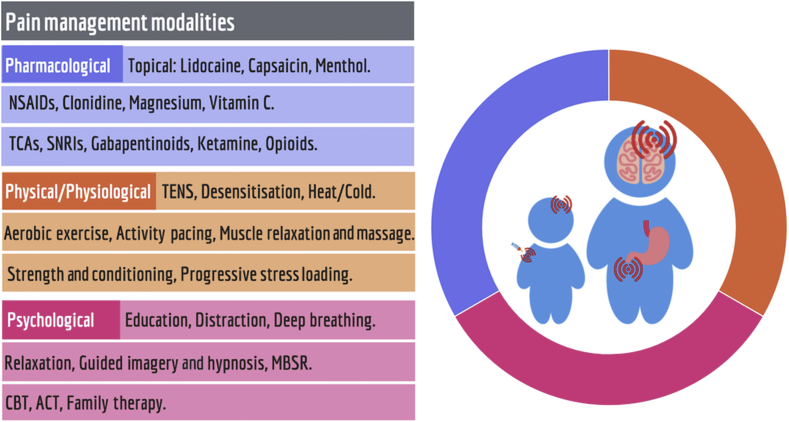

Fig 1.

Management along biopsychosocial principles aims for synergy between pharmacological, physical/physiological, and psychological treatments. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

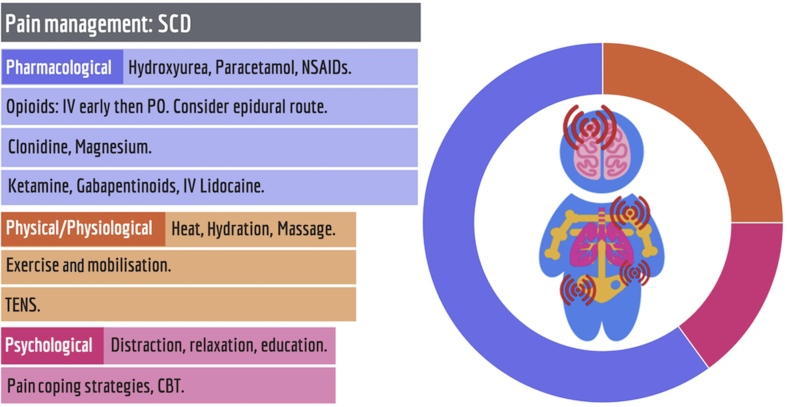

Fig 2.

The evidence base for the management of acute painful crises in sickle cell disease (SCD) supports predominantly pharmacological management. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TENS; transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

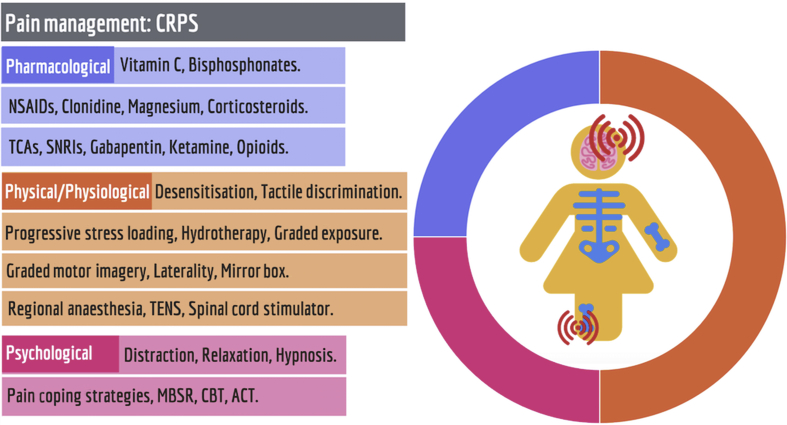

Fig 3.

The evidence base for the management of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) in children and young people supports predominantly physical/physiological modalities. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; SNRIs, selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

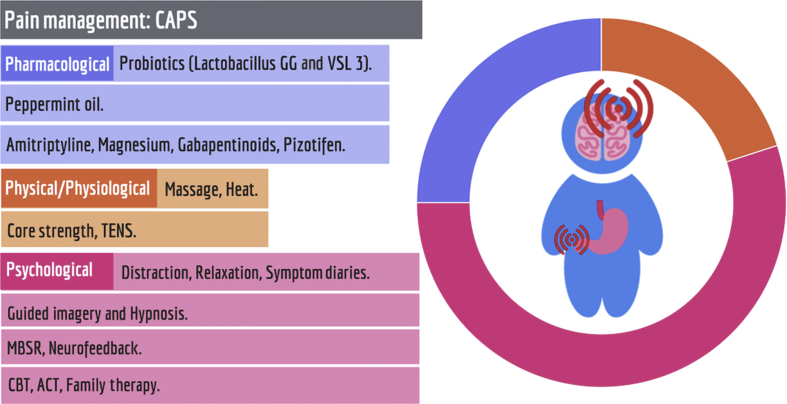

Fig 4.

The evidence base for the management of centrally-mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS) supports predominantly psychological interventions. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Achieving these objectives frequently necessitates the use of strong opioids that are administered intravenously in the first instance, until adequate pain relief is achieved. Treatment may then be switched to oral opioids or i.v. opioids can be maintained, either as patient-controlled analgesia or a continuous infusion as deemed appropriate. Epidural opioids have been used with success in severe cases with refractory pain.13 Opioid rotation may be necessary because of suboptimal analgesia or intolerable adverse effects. Applying generic acute pain algorithms to this group of patients would be considered substandard care and it would be advisable for institutions to have a separate protocol for SCD that can be adapted to individual patient needs while meeting the quality standard set out by NICE.

Preventative strategies for vaso-occlusion, ischaemic tissue damage, and development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia may need to be addressed. Hydroxyurea is thought to boost the levels of fetal haemoglobin, thus lowering the amount of sickle haemoglobin resulting in less abnormal haemoglobin polymerisation. Psychological support is important to tackle concomitant mood disorders, impart coping skills, provide school support, and address unstable family dynamics.14

CRPS

CRPS is a chronic pain syndrome that usually affects one limb following injury or trauma. It is characterised by persistent disproportionate pain and sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor, and trophic changes. CRPS in children differs from the adult condition in so much as there is a marked female preponderance and the lower limb is more commonly affected. The peak incidence is 13 yr old. There is some evidence of a genetic link and of a possible association with mitochondrial disorders.15 Several studies have described a ‘psychological phenotype’ in children who develop CRPS: they tend to be perfectionistic high-achievers with a history of parental marital discord.16 Even if present, such psychosocial factors should not be the most immediate concern. An analogy would be the importance of managing hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in a patient with an acute coronary syndrome: while they do influence outcome, they are not the most immediate priority of therapy. In the adult CRPS literature, the importance of premorbid psychological factors has been disputed.17

CRPS in children has several different clinical trajectories, which range from a milder form that responds to simple analgesics in combination with early and intensive physiotherapy18 to more refractory presentations that require intensive multidisciplinary input. Other trajectories involve presentations that wax and wane; therefore, not all signs and symptoms may be present at the time of examination. There are no validated diagnostic criteria for CRPS in children, so failure to meet adult criteria may not completely exclude the possibility that the presentation is indeed CRPS. It may be preferable to refer ‘CRPS-probable’ cases to a specialist paediatric pain service who see larger numbers of such cases. The condition can also be known to spread or migrate to other limbs: this is supported by functional magnetic resonance imaging and neurophysiological findings suggestive of changes in central sensory processing.19 There is no unified ‘gold-standard’ treatment for CRPS and the evidence base in paediatrics is poor. The available evidence recommends an emphasis upon functional restoration within a multidisciplinary approach, with physical therapies as the cornerstone of management. Psychological support, pharmacotherapy, and interventional techniques such as sympathetic or somatic nerve blocks are used to facilitate this. Prompt diagnosis, early intervention, and avoidance of isolated drug therapy are essential to limit limb disuse and disease progression.8 There are three clinical practice guidelines available on CRPS that have synthesised the available evidence.20, 21, 22 Only one guideline specifically addressed paediatric CRPS and supported the primacy of physiotherapy and occupational therapy in its management. Data in adults shows time-sensitive beneficial effects from the use of vitamin C (50 mg kg−1 day−1 to a maximum of 3 g) as prophylaxis following trauma21 and for bisphosphonates in early CRPS when there is a documented bone fracture.21

Centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome

Centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS), formerly functional abdominal pain, typically occurs in younger children aged 4–11 yr of age. Abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms are frequently a comorbid feature of other pain presentations such as hypermobility and CRPS. CAPS, however, is a primary pain disorder that, like fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, or temporomandibular joint dysfunction, appears to be a regional manifestation of a central sensitivity syndrome.23 Of interest, and a note of caution for the longitudinal management of these younger children, some will subsequently develop widespread musculoskeletal pain, while another subset will ultimately be diagnosed with organic gastrointestinal disease such as coeliac or inflammatory bowel disease as teenagers.24

Much of the literature on the aetiology, and correspondingly the treatment, of CAPS has focused on psychological factors. There is a trend towards CAPS within families, however it appears that any genetic susceptibility is very strongly mediated by parental, familial, and other psychosocial factors.24 That the management of CAPS then involves predominantly psychological interventions can be misunderstood by children and their parents as dismissing their pain experience as ‘all in their head’. Particularly for younger children, using metaphors grounded in their own experiences is useful in gaining acceptance of a biopsychosocial explanation for their pain and help them embark upon functional rehabilitation. One helpful metaphor is to frame their pain as ‘a software problem as opposed to a hardware problem’. Therefore, the solution is ‘a software update of new (physical and) thinking skills, as well as medication’. It is also helpful to emphasise that over two thirds of children with CAPS improve, but only when they engage with all dimensions of care. After simple first-line techniques such as distraction, relaxation, and pain education, the intervention with the greatest reported efficacy for CAPS is hypnosis, with 85% remission at 1 yr and 68% remission at 5 yr.25 The next most studied and most effective is cognitive behavioural therapy.26 More recently, attention has turned to other treatments such as neurofeedback and meditation-based interventions such as mindfulness, both as stand-alone interventions and as part of a larger package of care such as in acceptance and commitment therapy.

Currently there is no evidence that dietary changes, either exclusion diets or the addition of fibre, impact upon pain in CAPS. However there is evidence for nutraceutical options for treating CAPS including probiotics, e.g. LGG and VSL3, and peppermint oil.26 When considering adjuvant analgesics, such as tricyclic antidepressants or gabapentinoids, our preference is for amitriptyline, as it has activity at multiple receptors, has the lowest number needed to treat and improves sleep quality. Amitriptyline 0.1–0.5 mg kg−1 at night can worsen constipation; combining it with 30 mg kg−1 day−1 of magnesium oxide or citrate can offset this as oral magnesium salts have an osmotic laxative action in addition to analgesic effects. Pizotifen, a serotonin antagonist, reduces pain in abdominal migraine,27 however its efficacy in other painful abdominal presentations has not been studied.

Conclusion

While complex pain conditions in children and young people may have complex solutions, those solutions may be broken down into more manageable components that follow a common 3P framework regardless of the specific pain presentation. However, a common framework does not necessarily mean generic or homogenous treatment plans, and each domain, pharmacological, physical/physiological, and psychological, may be more prominent for different conditions and at different points in a patient's treatment. It is the synergistic interaction of all domains that leads to successful treatment outcomes consistent with emerging evidence and current best practice.

Declaration of interests

None declared.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) can be accessed at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Sachin Rastogi BSc (Hons) MB ChB FRCA FFPMRCA is Consultant in Anaesthesia & Pain Medicine at the Great North Children's Hospital and Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. He set up and is the clinical lead for the paediatric chronic pain service at the Great North Children's Hospital. His research interests relate to neuropathic pain in children; he authored a chapter on Drugs for Neuropathic Pain in the Oxford Textbook of Paediatric Pain.

Kevin Finbarr McCarthy MB BCh BAO PhD FCARCSI FFPMCAI is Consultant in Paediatric Anaesthesia & Pain Medicine, and medical lead for complex pain at Our Lady's Children's Hospital Crumlin and Temple St Children's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. He undertook a PhD in pain physiology and is a Clinical Senior Lecturer with the Department of Paediatrics, Trinity College Dublin. He is on the board of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the CAI. His clinical and research interests include pain education and novel analgesics.

Matrix codes: 1D02, 2E03, 3E00

References

- 1.Roth R.S., Geissner M.E., Williams D.A. Interventional pain medicine: retreat from the biopsychosocial model of pain. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2:106–116. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betsch T.A., Gorodzinsky A.Y., Finley G.A., Sangster M., Chorney J. What’s in a name? Healthcare providers' perceptions of pediatric pain patients based on diagnostic labels. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:694–698. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedrichsdorf S.J., Giordano J., Desai Dakoji K., Warmuth A., Daughtry C., Schulz C.A. Chronic pain in children and adolescents: diagnosis and treatment of primary pain disorders in head, abdomen, muscles and joints. Children (Basel) 2016;3:42. doi: 10.3390/children3040042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walther-Larsen S., Pedersen M.T., Friis S.M. Pain prevalence in hospitalized children: a prospective cross-sectional survey in four Danish university hospitals. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;61:328–337. doi: 10.1111/aas.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groenewald C.B., Rabbitts J.A., Schroeder D.R., Harrison T.E. Prevalence of moderate–severe pain in hospitalized children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabbitts J.A., Fisher E., Rosenbloom B.N., Palermo T.M. Prevalence and predictors of chronic postsurgical pain in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2017;18:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simons L.E., Logan D.E., Chastain L., Cerullo M. Engagement in multidisciplinary interventions for pediatric chronic pain: parental expectations, barriers, and child outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:291–299. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cf59fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nazareth M., Richards J., Javalkar K. Relating health locus of control to health care use, adherence, and transition readiness among youths with chronic conditions, North Carolina, 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E93. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy K. Language matters: therapeutic metaphor in paediatric pain. Pain News. 2014;12:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandow A.M., Farley R.A., Panepinto J.A. Neuropathic pain in patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:512–517. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sickle cell disease: managing acute painful episodes in hospital. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg143 (accessed 21 January 2017). [PubMed]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sickle cell disease. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs58 (accessed 21 January 2017).

- 13.New T., Venable C., Fraser L. Management of refractory pain in hospitalized adolescents with sickle cell disease: changing from intravenous opioids to continuous infusion epidural analgesia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:398–402. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dampier C., Barakat L. Pain in sickle cell disease. In: McGrath P.J., Stevens B.J., Walker S.M., Zempsky W.T., editors. Oxford Textbook of paediatric pain. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2014. pp. 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashimoto T., Baldwin E.E., Gold J.I., Boles R.G. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: complex regional pain syndrome type I in children with mitochondrial disease and maternal inheritance. Arch Dis Child. 2009;93:390–397. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.123661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wager J., Brehmer H., Hirschfeld G., Zernikow B. Psychological distress and stressful life events in pediatric complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Res Manag. 2015;20:189–194. doi: 10.1155/2015/139329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beerthuizen A., van 't Spijker A., Huygen F.J., Klein J., de Wit R. Is there an association between psychological factors and the Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type 1 (CRPS1) in adults? A systematic review. Pain. 2009;145:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherry D.D., Wallace C.A., Kelley C., Kidder M., Sapp L. Short- and long-term outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome type I treated with exercise therapy. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:218–223. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissmann R., Uziel Y. Pediatric complex regional pain syndrome: a review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14:29. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harden R.N., Oaklander A.L., Burton A.W. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edn. Pain Med. 2013;14:180–229. doi: 10.1111/pme.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez R.S., Zollinger P.E., Dijkstra P.U. Evidence based guidelines for complex regional pain syndrome type 1. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royal College of Physicians. Pain: complex regional pain syndrome. Available from https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/pain-complex-regional-pain-syndrome (accessed 5 February 5 2017).

- 23.Yunus M.B. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:339–356. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown L.K., Beattie R.M., Tighe M.P. Practical management of functional abdominal pain in children. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:677–683. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbott R.A., Martin A.E., Newlove-Delgado T.V. Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10:1. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010971.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutten J.M., Korterink J.J., Venmans L.M., Benninga M.A., Tabbers M.M. Nonpharmacologic treatment of functional abdominal pain disorders: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;135:522–535. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weydert J.A., Ball T.M., Davis M.F. Systematic review of treatments for recurrent abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e1–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]