Key points.

-

•

Exposure to a contrast agent is associated with acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) and the cause is likely to be multifactorial.

-

•

Risk factors for CA-AKI include chronic kidney disease (CKD), old age and hypovolaemia.

-

•

Alternative imaging techniques should be considered for patients at high risk of CA-AKI.

-

•

Expansion of intravascular volume and using lower osmolality contrast agents reduce the risk of CA-AKI.

Learning objectives.

By reading this article you should be able to:

-

•

Discuss the current evidence for the association between contrast administration and development of AKI.

-

•

Identify patients at high risk of developing CA-AKI.

-

•

Implement preventative measures to reduce the risk of CA-AKI.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common, occurring in more than 15% of patients admitted to hospital as an emergency.1 AKI often indicates severe systemic dysfunction and can lead to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and increased mortality. Early proactive recognition, prevention and active management can reduce the incidence of AKI.

Contrast-associated AKI (CA-AKI) is typified by a deterioration of renal function in the days after intravascular injection of a contrast agent. Historically, the prevalence of CA-AKI was thought to be substantial, and considered to be a direct effect of iodinated contrast agents. Newer evidence questions the prevalence of CA-AKI and the significance of contrast in contributing towards AKI.2 In this review we describe the pathophysiological mechanisms and discuss the difference between contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI) and CA-AKI; research data have not yet clearly distinguished these entities. Regardless of aetiology, AKI can occur after giving an intravascular contrast agent. We discuss how to identify those patients at high risk of CA-AKI and the evidence-based preventative measures that should be taken to reduce the risk.

History and discovery of CA-AKI

CA-AKI was first described in the 1950s in patients undergoing intravenous (i.v.) pyelography using contrast agents.3 Larger studies that followed showed a very high incidence of CA-AKI. It became widely believed that CA-AKI was associated with substantially increased mortality and morbidity, including the frequent need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). Unfortunately, many of these early studies did not include control groups, therefore only demonstrated association with and not causation of the AKI. A meta-analysis examining the incidence of CA-AKI after an i.v. contrast agent found that only 13 studies of 1489 papers had suitable control groups.2

Definition

CI-AKI is the subgroup of CA-AKI that can be linked causally to giving contrast media (i.e. ‘contrast-induced’). ‘Contrast-induced nephropathy’ was a historic definition, replaced by CI-AKI, the term endorsed by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).4 The differences between CI-AKI and CA-AKI have become blurred in the literature. This makes accurate reporting of the prevalence of CA-AKI problematic and has led to publication of poor quality data on the risk factors, prevention and treatments. KDIGO defines CI-AKI, after exposure of a contrast agent, as one of the following:

-

(i)

an increase in serum creatinine by ≥26.5 μmol L−1 within 48 h; or

-

(ii)

an increase in serum creatinine by ≥1.5-fold from baseline within 1 week; or

-

(iii)

urine output <0.5 ml kg−1 h−1 of body weight for >6 consecutive hours.

The creatinine definition is the most sensitive, but its specificity is poor.

Without appropriate randomised trials, it is impossible to attribute AKI after contrast to be specifically contrast-induced. We have therefore used the more inclusive term CA-AKI in this article. We believe what much of the literature describes as CI-AKI is most likely to be CA-AKI. As one example, a study by Ho and Harahsheh stated that 41% of 137 patients undergoing computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) developed CI-AKI, with 26% requiring RRT.5 However, 51% of the cohort were hypotensive, 39% required inotropic drugs and 50% received mechanical ventilation; this demonstrates how various causes of AKI have been attributed solely to contrast.

CA-AKI typically occurs within 48 h of receiving contrast with recovery expected, in most cases, over the next 5 days. Other causes of AKI, such as hypotension, embolic disease and medications should be considered, investigated and managed as necessary.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and creatinine clearance are widely used to describe renal function in stable patients, but are unreliable in patients with acute illness, when creatinine is preferred.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological mechanisms of CA-AKI are not completely understood. Contrast agents are thought to have both direct and indirect effects on renal function. Contrast is directly nephrotoxic to renal tubular cells by increasing tubular fluid viscosity, leading to changes in renal tubular cell polarity via redistribution of Na+/K+ ATPase pump expression, resulting in increased sodium delivery to the distal tubules. This causes endothelial cell apoptosis, necrosis and luminal obstruction, increased intratubular pressure and ultimately decreased glomerular filtration.

The indirect effect of contrast agents results in alterations to vasoactive substances, such as renin, angiotensin, endothelin, nitric oxide and prostaglandins. This causes reduced glomerular blood flow and oxygen delivery to the metabolically active nephron. Contrast also increases blood osmolality and viscosity. Collectively, these mechanisms, especially in vulnerable renal tissues, can lead to impaired renal function.

Attributing AKI after a contrast agent solely to these mechanisms is unproved. Non-contrast mediated mechanisms also are at play. These include, for example, concurrent haemodynamic instability, dehydration, other nephrotoxic agents, the pathology for which the contrast agent is being given and a patient's comorbidities.

Types of contrast

Contrast is used to enhance tissue visibility, improve diagnostic efficacy or make therapeutic procedures possible. CA-AKI is associated with giving an iodinated contrast agent. However, non-iodinated contrast agents, including gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs), may also induce AKI (discussed later).

High osmolality contrast agents, used historically, have approximately four times the osmolality of blood. These have been largely replaced with either low osmolality agents, which are still hyperosmolar (approximately 600 mOsm kg−1), with an osmolality twice that of blood (serum 290 mOsm kg−1), or iso-osmolar agents.

A randomised trial demonstrated a 3.3 times greater risk of developing AKI in those receiving a high osmolality contrast agent (diatrizoate, >1550 mOsm kg−1) compared with a lower osmolality agent (iohexol, <844 mOsm kg−1).6 High osmolality contrast agents have been predominantly abandoned by radiological departments in the UK and the use of iso-osmolar and low-osmolar agents is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology, as these carry a lower risk of CA-AKI.7

Study heterogeneity makes it difficult to ascertain the different incidence of AKI between iso-osmolar and low-osmolar contrast agents, but they are lower than high-osmolar agents. The randomised, double blind Cardiac Angiography in Renally Impaired Patients (CARE) trial directly compared iso-osmolar and low-osmolar contrast agents in those with CKD undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (GFR 20–59 ml min−1 1.73−2).8 The incidence of AKI after intra-arterial contrast in both groups was not significantly different (4.4% in the low-osmolarity group compared with 6.7% in the iso-osmolarity group, p=0.39), though the mean increase in serum creatinine was lower in those receiving low-osmolarity contrast.

Risk factors

The risk of developing CA-AKI depends on factors related to the patient, the procedure and the type of contrast (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Patient factors | Pre-existing renal disease (CKD or recent AKI) | eGFR<60 ml min −1 1.73 −2 |

| Elderly population | >75 yr | |

| Diabetes | Especially with associated renal disease (eGFR<40 ml min−1 1.73−2) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Cardiac failure, hypertension or vascular disease | |

| Concurrent nephrotoxic drugs | Including aminoglycosides, NSAID, antiviral drugs (e.g. acyclovir) | |

| Haemodynamic instability | Including hypovolaemia and sepsis. Where possible, administration of contrast should be delayed until hypotension is corrected. Intervention or scanning with contrast, however, should not wait for renal function assessment if early imaging outweighs the risk of delaying the procedure | |

| Procedural factors | Intra-arterial delivery, compared with the lower risk of i.v. delivery | The risk is highest with first-pass renal arterial exposure, for example injection into the left heart, thoracic aorta, suprarenal abdominal aorta or renal arteries |

| Contrast factors | Dose of contrast | High volumes of iodinated contrast >350 ml or >4 ml kg−1 |

| High-osmolality contrast | ||

| Repeated exposure to contrast | Especially <72 h |

Pre-existing renal dysfunction is the greatest patient-related risk factor for CA-AKI. Those patients with a normal baseline renal function have an estimated 1–2% risk of developing CA-AKI.4 The risk of CA-AKI is 5% in those with a pre-existing eGFR≥60 ml min−1 1.73−2; 10% at eGFR 45–59 ml min−1 1.73−2; 15% at eGFR 30–44 ml min−1 1.73−2; and 30% at eGFR<30 ml min−1 1.73−2.

The risk of CA-AKI with i.v. contrast for CT scans is low. A large meta-analysis showed no increased risk of CA-AKI with i.v. contrast compared with non-contrast CT scans; there were similar incidences of AKI (6.4% contrast vs 6.5% non-contrast), death or dialysis in both groups.2 However, this risk is likely to be increased in the patient who is critically unwell and those with other risk factors.

Patients who are given arterial contrast, compared with i.v., are a different group of patients, receive different doses of contrast and often experience procedure-related physiological changes, such as hypotension and arterial embolisation. Controlled studies comparing intra-arterial and i.v. contrast agents are not feasible, as the contrast is essential for arterial procedures.

Risk stratification tools, derived from large groups of patients, help to identify those at low or high risk of CA-AKI. Those deemed low risk can avoid unnecessary renal function tests or overburdensome preventative measures; patients at high risk can receive preventative measures with close follow-up, with the aim of reducing the occurrence of CA-AKI. Cumulative risk factors increase the possibility of developing AKI exponentially.4 Most of these risk tools are developed for cardiac interventions. One such tool, published by Mehran and colleagues, based on patients undergoing coronary interventions, can be seen in Table 2, Table 3.9 We are not aware of a risk score available for patients receiving i.v. contrast.

Table 2.

Risk factors for CA-AKI with percutaneous coronary interventions (reproduced and adapted with permission)9

| Risk factor | Relative integer score |

|---|---|

| Hypotension (systolic BP<80 mmHg requiring inotropic drugs) | 5 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 5 |

| Congestive cardiac failure (NYHA classification III/IV, history of pulmonary oedema, or both) | 5 |

| Age >75 yr | 4 |

| Anaemia (baseline haematocrit<39% male, <36% female) | 3 |

| Diabetes | 3 |

| Contrast media volume | 1 for each 100 ml |

| Creatinine ≥133 μmol L−1 | 4 |

| or | |

| eGFR | |

| 40–60 ml min−1 1.73−2 | 2 |

| 20–40 ml min−1 1.73−2 | 4 |

| <20 ml min−1 1.73−2 | 6 |

Table 3.

CA-AKI risk scoring model for percutaneous coronary interventions (reproduced and adapted with permission)9

| Risk score | Risk of CA-AKI (%) | Risk of needing RRT (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ≤5 | 7.5 | 0.04 |

| 6–10 | 14.0 | 0.12 |

| 11–16 | 26.1 | 1.09 |

| ≥16 | 57.3 | 12.6 |

Prognosis

In most patients, CA-AKI is transient and self-limiting, but for some it can lead to the development of de novo CKD or progression of pre-existing CKD.4 There are limited data in patients with end-stage renal failure on the development of CA-AKI. In early studies, RRT for CA-AKI was used in almost 4% in those with CKD.10 More recent studies provide a more relevant risk, demonstrating an incidence of CA-AKI of around 5% and only a small proportion of these patients go on to develop CKD (1%) or require long-term RRT (0.06%) with i.v. contrast.11

Multiple studies demonstrate that CA-AKI is associated with increased mortality, prolonged duration of hospital stay and other adverse outcomes, even mild significant deterioration in renal function that is not clinically significant. A US retrospective analysis of 27,608 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention showed that even a small increase in serum creatinine was associated with increased inpatient mortality.12

Prophylaxis

AKI, of any cause, increases the risk of developing CKD. CKD increases the need for RRT and has increased mortality. There are no suitably powered studies to date that demonstrate that prevention of CA-AKI improves mortality, but it does reduce the incidence of AKI and CKD. Although not proved specifically in CA-AKI, reducing the incidence of AKI may improve longer term outcomes by reducing CKD and mortality.

A pragmatic approach to patients undergoing contrast-enhanced procedures should include the use of evidence-based preventative measures in those at highest risk for AKI. Burdensome interventions should be avoided if unnecessary. A large number of interventions have been evaluated in the prevention of CA-AKI. Intravascular volume expansion is the only intervention with definitive benefit.

Numerous bodies have published guidelines in an effort to reduce the incidence of CA-AKI, including the American College of Radiology (ACR), the European Society of Urogenital Radiology, KDIGO, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Renal Association. Many of these guidelines are based on expert opinion with poor quality data, using studies without control groups.

Contrast agent

Modifiable factors are to minimise the volume of contrast agent, using low osmolarity or iso-osmolar contrast, and using non-iodinated contrast media. The volume of contrast agent given correlates with the risk of CA-AKI.13

Fluids

Intravascular volume expansion at the time of giving contrast may counteract both the indirect intra-renal haemodynamic changes and direct renal tubular toxic effects of contrast. It may reduce cellular damage by diluting the tubular concentration of contrast agent and is likely to decrease tubular fluid viscosity. Possibly more importantly, it may correct and optimise other concurrent causes of AKI, unrelated to giving contrast, such as dehydration.

Intravascular volume should be optimised in any patient receiving contrast. The exact volume and rate of fluids given is probably less important, but should be individualised to achieve euvolaemia. Oral fluid is adequate for those at low risk of CA-AKI and i.v. fluids are preferred for high-risk patients. Regarding i.v. fluids, isotonic sodium bicarbonate or isotonic sodium chloride could be used; the former may have additional benefits (discussed later), but the ideal rate and volume remains unclear. Exact fluid type should be considered in the context of any electrolyte and acid-base derangements. Evidence suggests that giving fluids reduces the incidence of CA-AKI but has minimal effect on the use of RRT or mortality.4

Oral hydration is not considered inferior to i.v. hydration at preventing CA-AKI.1 NICE recommends encouraging oral hydration before and after contrast agent exposure in adults at risk of CA-AKI in both outpatients and inpatients if appropriate. Outpatient hydration needs to be pragmatic and avoid unnecessary prolonged admission for i.v. fluids. It would seem reasonable to encourage oral fluid intake in the preoperative setting, whilst adhering to existing ‘nil-by-mouth’ guidelines. One study provided 500 ml water in the 4 h before giving contrast, stopping 2 h before the procedure and then another 600 ml water after contrast.14

NICE and KDIGO recommend i.v. rather than oral hydration for those at high risk of CA-AKI. Many varying regimes have been trialled with i.v. fluids, commonly including an infusion commencing 1 h before contrast agent administration and continuing for 3–6 h thereafter.4 Longer regimens (12 h post-contrast administration) have been shown to lower the incidence of AKI further.15 Achieving a urine output >150 ml h−1 for 6 h after giving contrast was associated with a reduced incidence of AKI.16 In some emergency circumstances it may not be feasible to optimise fluid status before giving contrast, but correction of hypotension should be attempted and fluids should be given afterwards. Forced euvolaemic diuresis with furosemide or mannitol has been shown to increase the incidence of CA-AKI.17

It is unclear what volume of i.v. fluid is best to prevent AKI. ACR guidelines recommend the use of i.v. saline 0.9% at 100 ml h−1 for 6–12 h before and 4–12 h after angiography.18 European Society of Cardiology guidelines advocate i.v. saline 0.9% at 1–1.5 ml kg−1 h−1 for 12 h before and up to 24 h after the procedure.7 The Prevention of Contrast Renal Injury with Different Hydration Strategies (POSEIDON) trial showed fluid titration to targeted left ventricular end diastolic pressures had a lower incidence of CA-AKI compared with the control group.19 Fluid should be administered judiciously in those at risk of fluid overload, for example concurrent heart failure or the elderly, who may develop pulmonary oedema, although the POSEIDON trial demonstrated a low incidence of adverse effects. However, the A Maastricht Contrast-Induced Nephropathy Guideline (AMACING) trial randomly assigned 660 patients deemed high risk for CA-AKI undergoing contrast procedures to receive either periprocedural i.v. isotonic saline or no i.v. fluids.20 There was no significant difference in the incidence of AKI between the hydration group and the no hydration group. It should be noted that the AMACING trial excluded those with eGFR<30 ml min−1 1.73−2, thereby omitting those potentially at highest risk of developing CA-AKI.

Most guidelines recommend i.v. hydration with either isotonic (1.26%) sodium bicarbonate or isotonic (0.9%) sodium chloride. The Prevention of Serious Adverse Events Following Angiography (PRESERVE) study showed equivalent values of i.v. isotonic sodium bicarbonate and isotonic sodium chloride in patients at high risk of CA-AKI after angiography (CA-AKI in 9.5% vs 8.3%, respectively [p=0.13]).21 Sodium bicarbonate may have additional therapeutic benefits, including urinary alkalisation and free radical scavenging, but a meta-analysis of 5686 patients showed no clinical benefit of sodium bicarbonate over sodium chloride.22 We are not aware of any trial that has compared giving a balanced crystalloid fluid with isotonic saline or isotonic sodium bicarbonate, despite the proved benefits of these fluids in other settings.

Pharmaceutical agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been extensively investigated for the prevention of CA-AKI. Data fails to provide a significant benefit in clinical outcomes, with either oral or i.v. NAC administration.21 NAC is not widely used in the UK and not recommended by NICE, but it is by KDIGO, despite having no effect on mortality, AKI or need for RRT.

There is insufficient evidence to support stopping diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. NICE advises consideration of temporarily stopping these medications in those with CKD with eGFR<40 ml min−1 1.73−2.1 It seems appropriate to avoid and stop nephrotoxic medications around the time of giving contrast agent, including NSAIDs. Metformin is not itself nephrotoxic but there is risk of developing lactic acidosis in severe AKI and it is advised to temporarily stop metformin after contrast is given.

Renal replacement therapy

Use of prophylactic RRT is not recommended for removing contrast agent, even in those at high risk of CA-AKI. Contrast agents are excreted predominantly by glomerular filtration, and elimination is delayed in those with renal dysfunction.23 Some 60–90% of contrast agent can be effectively removed by intermittent haemodialysis. However, evidence does not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of CA-AKI with prophylactic RRT use after giving contrast agents and it is currently not recommended by KDIGO.

Influence on decision making

Regardless of whether AKI after contrast is a marker or a mediator of adverse outcomes, it has an impact on clinical practice. Unnecessarily avoiding or postponing a contrast scan or procedure may deny or delay an accurate diagnosis or treatment. Patients with CKD are less likely to undergo coronary angiography than those with normal renal function and this may be partly because of concerns over CA-AKI.24 Avoiding contrast in patients with CKD occurs with other contrast-enhanced procedures. The topic is complex as this may equally signify the appropriate use of alternative imaging modalities that avoid contrast.

The use of a contrast agent in patients with CKD or high risk of CA-AKI should be discussed as part of an individualised multidisciplinary team discussion, including the patient, a renal physician, the radiologist and referring clinician. NICE recommends discussion with renal physicians in those on RRT (those with residual urine output may require dialysis after contrast) or with a renal transplant, but again this should not necessarily delay emergency imaging.1 A threshold eGFR<30 ml min−1 1.73−2 or a recent AKI are recommended by ACR as a trigger for discussion between the radiologist and referring clinician.18

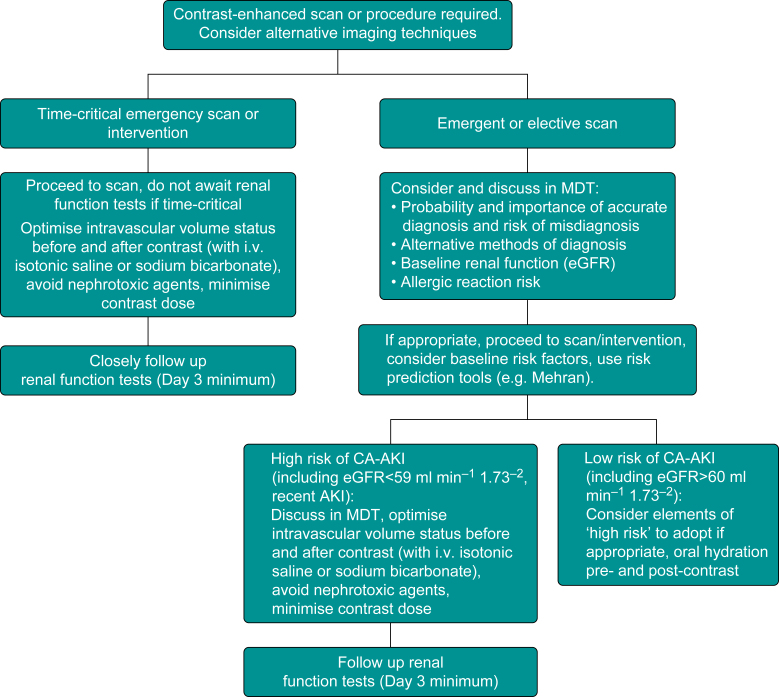

We propose a logical approach to management of patients receiving a contrast agent (see Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Decision-making aid for patients needing contrast-enhanced imaging or intervention.

Special circumstances

Gastrointestinal surgery

A recent prospective cohort study of more than 5000 patients undergoing both elective and emergency abdominal surgery found an overall incidence of AKI of 13.4%.25 There was no increased risk of postoperative AKI in those exposed to preoperative i.v. contrast scans (n=1249) using a propensity score-matched model.

Endovascular aneurysm repair

AKI after endovascular aneurysm repair and open aortic aneurysm repair is common and multifactorial; the incidence varies (up to 36%) because of differing definitions of AKI in the literature, but is most common in emergency open repair.26 There are multiple risk factors for AKI after endovascular aneurysm repair including: emergency procedures; guidewire manipulation in the renal vessels; embolisation of atheromatous plaque into renal vessels; perioperative hypotension; and the use of contrast. Significant AKI after AAA repair is associated with increased mortality. The same principles apply to reducing the risk of AKI as discussed previously.

Paediatrics

Risk factors for AKI in children include prematurity, postnatal infections, congenital heart disease and congenital kidney diseases. Children with these conditions are more likely to require contrast-enhanced scans and interventions. There are few studies examining CA-AKI in paediatric patients. Paul and colleagues found no AKI development in severely injured children after i.v. contrast for CT scanning.27 Preventative measures are largely extrapolated from adult research and clinical practice but lack primary evidence in the paediatric population.

Intensive care

Critically ill patients are at high risk of developing AKI for multiple reasons. A propensity score matched non-randomised trial of patients in ICU found an increased risk of AKI and dialysis in the contrast vs non-contrast group if eGFR was <45 ml min−1 1.73−2.28 However, without properly controlled studies, it is difficult to ascertain the significance of contrast agents in causing AKI in heterogeneous patients in ICU.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs)

Gadolinium chelates are used as a contrast agent in MRI scans. GBCAs in high doses are nephrotoxic, causing CA-AKI.29 The incidence of CA-AKI and allergic reaction are much lower with GBCAs than iodinated contrast agents. The Royal College of Radiologists recommends caution when using GBCAs in those with renal dysfunction and alternative imaging techniques should be considered. If needed, minimising the dose of GBCA will reduce the risk of CA-AKI.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare, but serious disorder that occurs in those with impaired renal function when exposed to GBCAs. Collagen disposition results in contractures and fibrosis of multiple systems: lung, liver, heart and muscle. Current GBCAs pose a much lower risk than historic agents; there is a <1% risk of developing NSF with newer GBCAs in those with renal dysfunction.30 To reduce the risk of NSF the GBCA dose should be limited, lower-risk GBCAs used, repeat contrast administration avoided within 7 days and GBCAs avoided in patiens with AKI. Initiation of intermittent haemodialysis is not recommended, but for those already on it, they should be dialysed within 24 h of giving a GBCA.

Conclusions

CA-AKI remains one of the leading causes of AKI, but its validity remains a clinical and research dilemma. To date, no RCTs have been performed to truly elucidate whether CI-AKI exists. The historically high incidence of CA-AKI is now much lower than previously reported. Iso-osmolar and low osmolality contrast agents do not appear to be significantly nephrotoxic. AKI does occur after the use of contrast, but this is likely to reflect multifactorial mechanisms, particularly in patients who are critically ill or those with significant risk factors.

We recommend proceeding with a contrast scan or intervention in the emergency setting, if deemed appropriate, and alternative imaging is not suitable, especially if i.v. contrast is given. An evidence-based multidisciplinary team discussion in elective situations is essential to highlight those at high risk of CA-AKI and weigh up the risks and benefits of obtaining an accurate diagnosis. In both settings, it is important to limit the dose and volume of contrast agent, and CA-AKI prophylaxis, namely intravascular volume expansion, should be given to those at high risk, with close follow-up of renal function.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) are accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Coralie Bingham FRCP PhD (honorary associate professor and consultant in renal medicine, Royal Devon & Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, UK) for reviewing this article before submission.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Matthew Everson BSc (Hons) MRCP FRCA is a specialty registrar in intensive care medicine and anaesthesia in the South West Peninsula Deanery. His interests are in perioperative medicine, vascular anaesthesia and medical education.

Kittiya Sukcharoen MRCP is an academic clinical fellow and specialty registrar in renal and general medicine in the South West Peninsula. She has research interests in monogenic renal disease and big data analysis.

Quentin Milner FRCA is a consultant anaesthetist with specialist interest in vascular anaesthesia.

Matrix codes: 1A02, 2A05, 3I00

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management. 2019. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148 Available from: [PubMed]

- 2.McDonald J., McDonald R., Comin J. Frequency of acute kidney injury following intravenous contrast medium administration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2013;267:119–128. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12121460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartels E., Brun G., Gammeltoft A. Acute anuria following intravenous pyelography in a patient with myelomatosis. Acta Med Scand. 1954;150:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1954.tb18632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Report of a working party; Boston: 2012. Clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho K., Harahsheh Y. Predicting contrast-induced nephropathy after CT pulmonary angiography in the critically ill: a retrospective cohort study. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0274-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudnick M., Goldfarb S., Wexler L. Nephrotoxicity of ionic and nonionic contrast media in 1196 patients: a randomized trial. Kidney Int. 1995;47:254–261. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullasari A., Victor S. Update on contrast induced nephropathy. E-journal Eur Soc Cardiol Cardiol Pract. 2014;13:4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon R., Natarajan M., Doucet S. Cardiac angiography in renally impaired patients (CARE) study. Circulation. 2007;115:3189–3196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehran R., Aymong E., Nikolsky E. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2004;44:1393–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman R., O’Donnell M., Share D. Nephropathy requiring dialysis after percutaneous coronary intervention and the critical role of an adjusted contrast dose. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1068–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02771-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kooiman J., Pasha S., Zondag W. Meta-analysis: serum creatinine changes following contrast enhanced CT imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2554–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisbord S., Chen H., Stone R. Associations of increases in serum creatinine with mortality and length of hospital stay after coronary angiography. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2871–2877. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cigarroa R., Lange R., Williams R. Dosing of contrast material to prevent contrast nephropathy in patients with renal disease. Am J Med. 1989;86:649–652. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho R., Javed N., Traub D. Oral hydration and alkalinization is noninferior to intravenous therapy for prevention of contrast- induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Interv Cardiol. 2010;23:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Molen A., Reimer P., Dekkers I. Post-contrast acute kidney injury. Part 2: risk stratification, role of hydration and other prophylactic measures, patients taking metformin and chronic dialysis patients: recommendations for updated ESUR Contrast Medium Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:2859–2869. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens M., McCullough P., Tobin K. A prospective randomized trial of prevention measures in patients at high risk for contrast nephropathy: results of the PRINCE Study: prevention of Radiocontrast Induced Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:403–411. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majumdar S., Kjellstrand C., Tymchak W. Forced euvolemic diuresis with mannitol and furosemide for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with CKD undergoing coronary angiography: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:602–609. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davenport M., Perazella M., Yee J. Use of intravenous iodinated contrast media in patients with kidney disease: consensus statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology. 2020;294:660–668. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019192094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brar S., Aharonian V., Mansukhani P. Haemodynamic-guided fluid administration for the prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: the POSEIDON randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1814–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijssen E., Rennenberg R., Nelemans P. Prophylactic hydration to protect renal function from intravascular iodinated contrast material in patients at high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (AMACING): a prospective, randomised, phase 3, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1312–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisbord S., Gallagher M., Jneid H. Outcomes after angiography with sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:603–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zapata-Chica C., Marquez D., Serna-Higuita L. Sodium bicarbonate versus isotonic saline solution to prevent contrast-induced nephropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colomb Med. 2015;46:90–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deray G. Dialysis and iodinated contrast media. Kidney Int Suppl. 2006;100:25–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau J., Anastasius M., Hyun K. Evidence-based care in a population with chronic kidney disease and acute coronary syndrome: findings from the Australian cooperative national registry of acute coronary care, guideline adherence and clinical events (CONCORDANCE) Am Heart J. 2015;170:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.STARSurg Collaborative Perioperative intravenous contrast administration and the incidence of acute kidney injury after major gastrointestinal surgery: prospective, multicentre cohort study. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1023–1032. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nonaka T., Kimura N., Hori D. Predictors of acute kidney injury following elective open and endovascular aortic repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018;11:298–305. doi: 10.3400/avd.oa.18-00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul K., Johnson J., Garwe T. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast is not associated with development of acute kidney injury in severely injured pediatric patients. Am Surg. 2019;85:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald J., McDonald R., Williamson E. Post-contrast acute kidney injury in intensive care unit patients: a propensity score-adjusted study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:774–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4699-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royal College of Radiologists . Report of a working party; London: 2019. Guidance on gadolinium-based contrast agent administration to adult patients. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schieda N., Blaichman J., Costa A. Gadolinium-based contrast agents in kidney disease: a comprehensive review and clinical practice guideline issued by the Canadian Association of Radiologists. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1–17. doi: 10.1177/2054358118778573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]