Abstract

The ruthenium-catalyzed [2 + 2] and homo Diels–Alder [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene with disubstituted alkynes are investigated using density functional theory (DFT). These DFT calculations provide a mechanistic explanation for observed reactivity trends with different functional groups. Alkynyl phosphonates and norbornadiene form the [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadduct, while other functionalized alkynes afford the respective [2 + 2] cycloadduct, in excellent agreement with experimental results. The computational studies on the potential energy profiles of the cycloadditions show that the rate-determining step for the [2 + 2] cycloaddition is the final reductive elimination step, but the overall rate for the [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition is controlled by the initial oxidative cyclization. Two distinct mechanistic pathways for the [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition, cationic and neutral, are characterized and reveal that Cp*RuCl(COD) energetically prefers the cationic pathway.

Introduction

Fused bicyclo[2.2.1]alkenes constitute a diverse class of chemical compounds and are powerful synthetic intermediates for the formation of complex, highly substituted ring systems.1a−1e Among these, bicyclo[2.2.1]hepta-2,5-diene, colloquially known as norbornadiene 1 (NBD), has been used as a key intermediate in the total synthesis of natural products such as prostaglandin endoperoxides PGH2 and PGG2,2cis-Trikentrin B,3 and β-santalol.4 Photochemical isomerization between NBD derivatives and quadricyclanes is of interest as a potential photoswitchable molecule that can undergo closed cycles of solar light harvesting and energy storage and release.5a−5f Because of the rigid bicyclic structure of NBD, there is significant ring strain energy in this molecule.6 In addition, the presence of two isolated double bonds homoconjugated through space7 along with two distinct faces (exo and endo) allows for unique reactivity not available in conventional alkenes.8 NBD’s inherent ring strain and dual-faced nature can be exploited for the facile establishment of multiple stereocenters in a single reaction by way of face-selective olefin chemistry (Scheme 1, 2)9a−9g or ring-opening reactions (Scheme 1, 9 and 7).10a−10e Of particular interest are transition-metal-catalyzed cycloadditions, as they are among the most powerful and frequently used methods for the construction of ring systems.11 Recent developments in transition-metal-catalyzed [2 + 1],12 [2 + 2] (Scheme 1, 8),13a−13d [2 + 2 + 1] (Scheme 1, 5),14a−14e [2 + 3] (Scheme 1, 4),15a−15e [2 + 2 + 2 + 2] (Scheme 1, 3),16a−16c and [2 + 2 + 6] (Scheme 1, 6)17 reactions have provided efficient methods for the production of 3–8 membered rings.

Scheme 1. Previously Reported Chemistry of Norbornadiene.

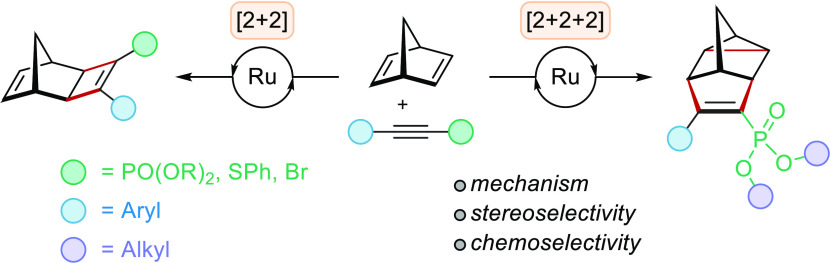

The development of ruthenium-catalyzed transformations has burgeoned over the past decade.18a−18e Among the various ruthenium complexes, Cp*RuCl(COD) has been found to be the catalyst of choice in many reactions such as [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions,19a−19c hydrogenations,20a−20c cross-benzannulations,21a−21e and Alder-ene reactions.22a,22b Our group, along with others, have been largely involved in the construction of cyclobutene adducts via ruthenium-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloadditions.23a−23u In 2011, our group described the ruthenium-catalyzed homo Diels–Alder (HDA) [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of alkynyl phosphonates (10, X = phosphonate) with NBD 1 to afford phosphonate-substituted deltacyclenes 12 (Scheme 2, right).24 In agreement with previously reported ruthenium-catalyzed cycloadditions of alkynes with bicyclic alkenes, a quick screen of substituted acetylenes (10, X ≠ phosphonate) resulted in the exclusive formation of [2 + 2] cycloadducts 11 (Scheme 2, left), suggesting that HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition is unique to the electronics of phosphonate-substituted alkynes when Cp*RuCl(COD) is used as the precatalyst (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Disubstituted Alkynes 10 and NBD 1 Using Cp*RuCl(COD) as the Catalyst.

Here, we pursue an in-depth investigation of the reaction mechanism by performing density functional calculations to map out the ruthenium-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene and alkynyl phosphonates. The results provide theoretical support on the chemoselectivity of the experimentally observed Ru-catalyzed cycloadducts.

Computational Details

All computations in this study were carried out with the Gaussian 16 C.01 suite of programs.25 Geometry optimizations of all of the intermediates and transition states were carried out at the Becke three-parameter hybrid functional26 combined with the Lee, Yang, and Parr (LYP) correlation functional,27 B3LYP, with the double-ζ basis set def2SVP28 and Grimme’s dispersion with Becke–Johnson damping (GD3BJ).29 The optimization was carried out without imposing any symmetry constraints. Solvent effects (solvent = N,N-dimethylformamide or DMF) were taken into account using the polarized continuum model (PCM) of Tomasi and co-workers30a,30b and were involved in all geometry optimization and frequency calculations. Although N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) was experimentally determined to be the optimal solvent for the reaction, DMF was chosen to be the solvent of choice in the calculations. NMP is not implemented in Gaussian and the physical parameters for NMP are not published in Cramer and Truhlar’s solvent database.31a,31b Given the similarity in structure and dielectric constant (DMF ε = 37.2; NMP ε = 33), we considered this a good approximation. Harmonic vibrational frequencies were computed to verify the nature of the stationary points. Low imaginary frequencies were obtained for selected intermediates and transition states (see the Supporting Information for explanation and analysis). To ensure that the transition states link the products to the expected reactants, the normal modes corresponding to the imaginary frequencies were animated. To obtain the free energies (temperature of 433.15 K, pressure of 1 atm), the zero-point energies, thermal motion, and entropy corrections were added to the total electronic energy. Optimized structures are illustrated using CYLview.32

The relative Gibbs free energy for each intermediate and transition state was calculated by taking the difference of the sums of the Gibbs free energy for each reaction coordinate from the reference point (norbornadiene 1, alkyne 10, and the Cp*Ru(COD)Cl precatalyst). In terms of each pathway, each [2 + 2] reaction coordinate was composed of ΔG433.15(COD + IN/TS), while each [2 + 2 + 2] reaction coordinate was composed of ΔG433.15 (COD + IN/TS + Cl–).

Results and Discussion

Discussion of the Mechanism

Previous studies have suggested that the neutral [Cp*RuCl] moiety 16 is likely to be the active catalytic species in the [2 + 2] cycloaddition.33a,33b Dissociation of one of the double bonds of the cyclooctadiene (COD) ligand from the Cp*Ru(COD)Cl precatalyst followed by the ligand association with the alkyne would provide complex 15 (Scheme 3). Upon dissociation of the COD ligand to form the coordinatively unsaturated species 16, either a second alkyne or NBD 1 could complex with 16 (Scheme 3). It has been noted that the number of equivalents of NBD and alkyne had a considerable effect on the efficacy of the reaction. Excess of the alkene component improved the yield of the desired cycloadduct, while the use of excess alkyne decreased the yield dramatically.33a,33b Because Ru is known to form stronger π-complexes with alkynes than with alkenes,34a,34b the formation of the coordinatively saturated complex 17 is hypothesized to inhibit the active catalytic cycle. An excess of alkene results in the complexation to the exo-face of NBD, affording complex IN1, starting the [2 + 2] catalytic cycle. Complexation of 16 with the endo-face of NBD was not investigated as an alternative complex, as the intermediate would not lead to the experimentally observed exo-cycloadducts. The full catalytic cycle for the [2 + 2] cycloaddition is constituted by three elementary steps (Scheme 4): coordination of the alkyne to the exo-face of NBD to afford species IN1; oxidative cyclization of the Ru–alkene–alkyne π-complex to provide metallacyclopentene IN2 via TS1–2; and reductive elimination of metallacyclopentene IN2 to form the final [2 + 2] cycloadduct 17. The HDA [2 + 2 + 2] pathway is thought to begin in a similar manner proposed by Trost and co-workers in their 1993 report on CpRu(COD)Cl-catalyzed bis-homo-Diels–Alder cycloadditions of COD with alkynes.35 The active cationic species is formed through the ionization of the chloride ligand under the condition of a polar solvent.36a,36b This coordinatively unsaturated species can complex to the endo-face on NBD to form species IN3; oxidative cyclization of the Ru–alkene–alkyne π-complex will provide metallacyclopentene IN4; migratory insertion of IN4 forms the second carbon–carbon bond; and reductive elimination of intermediate IN5 forms the last carbon–carbon bond, furnishing the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadduct 18. According to our calculations, the reductive elimination transition states TS2 have greater relative energy differences than the oxidative cyclization transition states TS1–2 in all cases. This indicates that TS2 is the rate-determining step for the [2 + 2] pathway (Scheme 3). Conversely, the initial oxidative cyclization TS3–4 possesses a relative energy difference that is greater than both the migratory insertion TS4–5 and the reductive elimination TS5, suggesting TS3–4 is the rate-determining step for the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] pathway (Scheme 4). To determine the preferred pathway, the energy difference between the two competing transition states TS2 and TS3–4 was compared. Because of the potential unsymmetrical nature of the disubstituted alkynes, two configurations of the alkyne, A and B, were considered throughout both pathways—these further two competing pathways were denoted by including either a or b in the numbering systems (ie INa1 vs INb1).

Scheme 3. Activation of the Cp*RuCl(COD) Precatalyst.

Scheme 4. Proposed Mechanisms for the Ru-Catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene 1 and Disubstituted Alkynes 10 for Path A (Top) and Path B (Bottom).

Effects of Phosphonate Substitution

We began studying the effects of phosphonate substitution on the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of NBD and alkynes. As reported by Kettles in 2011, both alkyl phosphonate moieties examined (Table 1, entries 1 and 2) were completely selective for the HDA adduct.24 Because the theoretical results discussed above addressed the reductive elimination TS2 and oxidative cyclization TS3–4 as the rate-determining steps for [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions, respectively, only these transition states will be discussed in detail (see the Supporting Information for the ΔG433.15‡ of all transition states). For the two alkynyl phosphonates, the relative Gibbs free energies at 433.15 K, ΔG433.15‡, for TS2 and TS3–4 with respect to the isolated reactants (NBD 1, alkyne 10, and Cp*RuCl(COD)) were calculated (see the Supporting Information). In both cases of alkyl substitution (Table 1, entries 1 and 2), the reductive elimination TSb2 was favored over TSa2. This is most likely due to the increased negative charge placed on the carbon adjacent to the phosphonate moiety, an effect known to accelerate reductive elimination. In terms of HDA [2 + 2 + 2], both alkynyl phosphonates preferred oxidative cyclization TSb3–4 over TSa3–4 by 2–4 kcal/mol. Once again, it was noticed that adjacent electron-withdrawing functional groups, through either inductive or mesomeric effects, lowered the activation barrier for reductive elimination. To determine the preferred pathway, the differences in relative Gibbs free energies at 433.15 K, ΔΔG433.15‡, with respect to their preceding intermediates were calculated. The energy differences between the four possible transition states were computed to determine the lowest energy rate-determining transition state, qualitatively revealing whether the [2 + 2] or HDA [2 + 2 + 2] pathway is preferred, as well as the order of carbon–carbon bonds formed. Among the four transition states, TSb3–4 was the lowest in free energy for both dimethylphosphonate 10b and diethylphosphonate 10a (Table 1, entries 1 and 2), indicating the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] pathway is more energetically favorable. The theoretically predicted activation energy differences are in good agreement with the experimentally observed products,24 as the lowest energy rate-determining step leads to the expected product. The potential energy profiles for the model reaction investigated, and the corresponding geometries for the most favored path, for the predicted Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions between NBD 1 and alkynyl phosphonate 10a are shown in Figure 1 (see the Supporting Information for energy profiles for alkyne 10b).

Table 1. Relative Free Energies in kcal/mol at 422.15 K in DMF with Respect to the Preceding Intermediate for the Ru-Catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene 1 with Alkynyl Phosphonates 10a,b.

Figure 1.

Potential energy profile of the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene 1 with alkynyl phosphonate 10a at 433.15 K in DMF. Energies are Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol with respect to separated reactants 1 + 10a + Cp*RuCl(COD).

Investigating Functionalized Acetylenes

To gain further insights into the dependency of the phosphonate moiety on the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of NDA 1 and alkynes 10, a series of alternative functional groups were examined (Table 2). For all of the reactions, the difference in relative Gibbs free energies at 433.15 K, ΔΔG433.15‡, for the reductive elimination TS2 and oxidative cyclization TS3–4 with respect to their preceding intermediates are given in Table 2. Replacement of the phosphonate moiety with sulfide 10d or bromide 10e flipped the reactivity with the [2 + 2] cycloaddition pathway, having lower activation energy than HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition (Table 2, entries 2 and 3). Again, the reductive elimination TS2 and oxidative cyclization TS3–4 are predicted to be rate-determining steps for [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions, respectively. The theoretically predicted activation energy differences at 433.15 K, ΔΔG433.15,DMF‡ are in good agreement with the experimentally observed products. The potential energy profiles for the alkynyl sulfide investigated, and the corresponding geometries for the most favored path, for the predicted Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions between NBD 1 and alkynyl phosphonates 10d are shown in Figure 2 (see the Supporting Information for energy profiles for alkynes 10e). Similar to the findings in Table 1, it is predicted that pathway B is favored for asymmetric alkynes, as it is energetically more favorable for reductive elimination TSb2 to occur adjacent to the heteroatom functional group. The relevant molecular diagrams of the rate-determining transition states and adjacent intermediates for Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (INb2, TSb2, and 16) and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (IN3, TSb3–4, and INb4) cycloadditions between NBD 1 and alkynes 10a and 10d are shown in Figures 3 and 4. Metal orbitals in IN3 and TS3–4 are similar, except for the notable charge transfer from the alkyne to the NBD ligand during TS3–4 (Figure 3). The positive orbital overlap, as seen in the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of TS3–4 can be attributed to the electron transfer from the alkyne to the alkene ligand with characteristics from the LUMO of IN3 being noted in the HOMO of IN4 (Figure 3). Like the alkynyl phosphonate (Figure 3), the alkynyl sulfide reaction undergoes a similar charge transfer from the alkyne to the NBD ligand via TS3–4 (Figure 4), however, with a smaller orbital overlap compared to 10a (Figure 3). In terms of [2 + 2] molecular diagrams, a charge transfer can be seen taking place in ruthenapentacycle via the reductive elimination TS2 transition state (Figures 3 and 4). Upon inspection of 10a (Figure 3), the frontier molecular orbitals in TS2 are dominated by antibonding characteristics, which may explain the high-energy transition state. On the other hand, 10d exhibits a positive orbital overlap in TS2 (Figure 4). This difference in the bonding nature may explain the preferential [2 + 2] and [2 + 2 + 2] pathways for 10a and 10d, respectively. The relevant geometries with Mulliken charges for the alkynyl phosphonate and sulfide are given in Figures 5 and 6, respectively.

Table 2. Relative Free Energies in kcal/mol at 433.15 K in the DMF solution with Respect to the Preceding Intermediate for the Ru-Catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene 1 with Acetylenes 10a,c,d.

Figure 2.

Potential energy profile for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene 1 with alkynyl phosphonate 10d at 433.15 K in DMF. Energies are Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol with respect to separated reactants 1 + 10d + Cp*RuCl(COD).

Figure 3.

Frontier

orbital isosurface plots (isosurface value = 0.03  ) of the rate-determining transition states

and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (right) and

HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (left) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl

phosphonate 10a at 433.15 K in DMF in the ground states

taken from Figure 1. Surfaces computed at the B3LYP/def2SVP level of theory with eigenvalues

converted to kcal/mol.

) of the rate-determining transition states

and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (right) and

HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (left) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl

phosphonate 10a at 433.15 K in DMF in the ground states

taken from Figure 1. Surfaces computed at the B3LYP/def2SVP level of theory with eigenvalues

converted to kcal/mol.

Figure 4.

Frontier orbital isosurface

plots (isosurface value = 0.03  ) of the rate-determining transition states

and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (right) and

HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (left) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl

phosphonate 10d at 433.15 K in DMF in the ground states

taken from Figure 2. Surfaces computed at the B3LYP/ def2SVP level of theory with eigenvalues

converted to kcal/mol.

) of the rate-determining transition states

and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (right) and

HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (left) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl

phosphonate 10d at 433.15 K in DMF in the ground states

taken from Figure 2. Surfaces computed at the B3LYP/ def2SVP level of theory with eigenvalues

converted to kcal/mol.

Figure 5.

Mulliken charges of the rate-determining transition states and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (top) and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (bottom) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl phosphonate 10a at 433.15 K in DMF.

Figure 6.

Mulliken charges of the rate-determining transition states and adjacent intermediates for the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] (top) and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] (bottom) cycloadditions of NBD 1 with alkynyl phosphonate 10d at 433.15 K in DMF.

Effects of Aryl Substitution

For greater completeness and reliability, we studied four more reactions: NBD 1 with aryl-substituted diethylphosphonate alkynes 10e–h (Table 3). For all four reactions, the differences in relative Gibbs free energies at 433.15 K, ΔΔG433.15‡ are given in Table 3. In agreement with dimethylphosphonate 10b or diethylphosphonate 10a (Table 1), the lowest energy rate-determining step corresponds to the oxidative cyclization TS3–4 in the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycle with pathway B being a more energetically accessible route to the deltacyclane product 18 (Table 3) (the energy profile diagrams for the five alkynyl phosphonates 10e–h investigated can be found in the Supporting Information). The theoretically predicted activation energy differences are in good agreement with the experimentally observed products,24 as the lowest energy rate-determining step leads to the expected product.

Table 3. Relative Free Energies in kcal/mol at 433.15 K in the DMF solution with Respect to the Preceding Intermediate for the Ru-Catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene 1 with Alkynyl Phosphonates 10a,e–h.

Cationic versus Neutral Mechanism

Previous reports on the Ru-catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of NBD 1 have suggested alternative catalytic cycles to the one presented in this report. In 2004, Tenaglia and co-workers reported the Ru-catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of NBD using RuCl2(PPh3)2(NBD) as the precatalyst.37 The mechanistic rationale for the observed results involved a neutral ruthenium species shuttling between 2+ and 4+ oxidation states. Although different mechanistic pathways may account for the HDA reaction depending on the proposed active catalytic species, we were interested if our precatalyst, Cp*RuCl(COD), could go through a neutral catalytic cycle. The exchange of the COD ligand for NBD would generate the 18-electron complex IN6 (Scheme 5). The oxidative coupling of NBD to Ru allows for the formation of ruthenacyclobutane as a part of the 16-electron tetracyclic framework IN7, which can coordinate to the alkyne partner 10 to afford IN8. Migratory insertion of the alkyne would form ruthenacyclohexane IN9. Reductive elimination of IN9 accounts for the formation of deltacyclane 18, as well as the regeneration of IN6 by coordination of NBD 1. As described in the previous catalytic cycle (Scheme 4), two configurations of the alkyne, A and B, were considered throughout the pathway.

Scheme 5. Proposed Mechanism for the Neutral Ru-Catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Norbornadiene 1 and Disubstituted Alkyne 10.

To address the possibility of a neutral pathway, we studied our model reaction: the Ru-catalyzed cycloaddition of alkyne 10a and NBD 1. The differences in relative Gibbs free energies at 433.15 K, ΔΔG433.15‡, for the four transition states with respect to their preceding intermediate are given in Table 4. The oxidative cyclization TS6–7 has an energy barrier (11.1–31.9 kcal/mol) greater than alkyne association TS7–8, migratory insertion TS8–9, and reductive elimination TS9 transition states. This indicates that the oxidative cyclization is rate-determining for the overall neutral pathway. Comparing the energies for the rate-determining steps for cationic (TS3–4) and neutral (TS6–7) mechanisms, we see a strong potential energy difference of 18.6–23.8 kcal/mol (TS3–4–TS6–7), suggesting that the cationic mechanism is the preferred pathway. The potential energy profile for the neutral pathway investigated, and the corresponding geometries for the most favored path, for the predicted Ru-catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions between NBD 1 and alkynyl phosphonates 10a are shown in Figure 7.

Table 4. Relative Free Energies in kcal/mol at 433.15 K in the DMF solution with Respect to the Preceding Intermediate for the Ru-Catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene 1 with Alkynyl Phosphonates 10a via a Neutral Mechanism.

Figure 7.

Potential energy profile of the PCM solvation model for the Ru-catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene 1 with alkynyl phosphonate 10a in DMF via a neutral mechanism at 433.15 K in DMF. Energies are Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol with respect to separated reactants 1 + 10a + Cp*RuCl(COD).

Conclusions

In summary, the mechanism and chemoselectivity of the Ru-catalyzed [2 + 2] and HDA [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions of norbornadiene with disubstituted alkynes have been studied by DFT calculations. We performed hybrid DFT calculations to address the unexplored mechanism of the Ru-catalyzed HDA [2 + 2 + 2] of norbornadiene. Two mechanistic pathways were investigated, the cationic and neutral reactions. In both cases, the oxidative cyclization step was found to be a rate-determining step in the whole catalytic cycle. Under the reaction conditions explored, we found the cationic pathway is favored over the neutral pathway by 18.6–23.8 kcal/mol. The results provide theoretical support toward the unique reactivity of alkynyl phosphonates. In good agreement with experimental results, calculations revealed that the HDA [2 + 2 + 2] pathway is more energetically favorable than the [2 + 2] pathway with alkynyl phosphonates. Likewise, replacement of the phosphonate moiety with a bromide or sulfide group flipped the reactivity, with the [2 + 2] pathway being favored. In combination with these experimental results, the theoretical studies presented herein may shift the understanding of Ru-catalyzed cycloadditions and the effects of alkynyl functionality.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant (W.T.) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. A.P. and L.D.C. acknowledge Compute Canada for providing access to supercomputing resources. A.P. also acknowledges NSERC for financial support through the CGS-M Scholarship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05499.

Additional free energy diagrams; listing of Cartesian coordinates; and total energies for the optimized geometries of calculated species (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Rayabarapu D. K.; Cheng C. H. New Catalytic Reactions of Oxa-and Azabicyclic Alkenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 971–983. 10.1021/ar600021z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lautens M.; Fagnou K.; Hiebert S. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Enantioselective Ring-Opening Reactions of Oxabicyclic Alkenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 48–58. 10.1021/ar010112a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Boutin R.; Koh S.; Tam W. Recent Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Reactions of Oxabenzonorbornadiene. Curr. Org. Synth. 2018, 16, 460–484. 10.2174/1570179416666181122094643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tam W.; Jack K.; Goodreid J.; Cockburn N. Transition Metal-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions Between Bicyclic Alkenes and Alkynes. Curr. Org. Synth. 2009, 6, 219–238. 10.2174/157017909788921907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Khan R.; Chen J.; Fan B. Versatile Catalytic Reactions of Norbornadiene Derivatives with Alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 1564–1601. 10.1002/adsc.201901494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Shibasaki M.; Nicolaou K. C.; Malmsten C. L.; Samuelsson B. Simple, Stereocontrolled Total Synthesis Fof a Biologically Active Analog of the Prostaglandin Endoperoxides (PGH2, PGG2). Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 737–740. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77938-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.; Ikeda I.; Kawabe T.; Mori S.; Kanematsu K. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Cis-Trikentrin B. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 3406–3416. 10.1021/jo951767q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Miyamoto O.; Inoue S.; Honda K. Stereospecific Synthesis of (±)-β-Santalol. Chem. Lett. 1981, 8, 1183–1184. 10.1246/cl.1981.1183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mansø M.; Petersen A. U.; Wang Z.; Erhart P.; Nielsen M. B.; Moth-Poulsen K. Molecular Solar Thermal Energy Storage in Photoswitch Oligomers Increases Energy Densities and Storage Times. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1945 10.1038/s41467-018-04230-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ikezawa H.; Kutal C.; Yasufuku K.; Yamazaki H. Direct and Sensitized Valence Photoisomerization of a Substituted Norbornadiene. Examination of the Disparity between Singlet- and Triplet-State Reactivities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 1589–1594. 10.1021/ja00267a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Spivack K. J.; Walker J. V.; Sanford M. J.; Rupert B. R.; Ehle A. R.; Tocyloski J. M.; Jahn A. N.; Shaak L. M.; Obianyo O.; Usher K. M.; Goodson F. E. Substituted Diarylnorbornadienes and Quadricyclanes: Synthesis, Photochemical Properties, and Effect of Substituent on the Kinetic Stability of Quadricyclanes. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1301–1315. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Dreos A.; Börjesson K.; Wang Z.; Roffey A.; Norwood Z.; Kushnir D.; Moth-Poulsen K. Exploring the Potential of a Hybrid Device Combining Solar Water Heating and Molecular Solar Thermal Energy Storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 728–734. 10.1039/C6EE01952H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Philippopoulos C.; Economou D.; Economou C.; Marangozis J. Norbornadiene-Quadricyclane System in the Photochemical Conversion and Storage of Solar Energy. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1983, 22, 627–633. 10.1021/i300012a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Brummel O.; Waidhas F.; Bauer U.; Wu Y.; Bochmann S.; Steinrück H. P.; Papp C.; Bachmann J.; Libuda J. Photochemical Energy Storage and Electrochemically Triggered Energy Release in the Norbornadiene-Quadricyclane System: UV Photochemistry and IR Spectroelectrochemistry in a Combined Experiment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 2819–2825. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury P. R.; Goddard J. D.; Tam W. Ring Strain Energies: Substituted Rings, Norbornanes, Norbornenes and Norbornadienes. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 8103–8112. 10.1016/j.tet.2004.06.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domelsmith L. N.; Mollere P. D.; Houk K. N.; Hahn R. C.; Johnson R. P. Photoelectron and Charge-Transfer Spectra of Benzobicycloalkenes. Relationships between Through-Space Interactions and Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 2959–2965. 10.1021/ja00478a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam W.; Cockburn N. Thieme Chemistry Journal Awardees—Where Are They Now? Bicyclic Alkenes: From Cycloadditions to the Discovery of New Reactions. Synlett. 2010, 1170–1189. 10.1055/s-0029-1219780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Trecker D. J.; Henry J. P. Free-Radical Additions to Norbornadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3204–3212. 10.1021/ja00903a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yoo W. J.; Tsui G. C.; Tam W. Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki Couplings of 2,3-Dibromonorbornadiene: Synthesis of Symmetrical and Unsymmetrical Aryl-Substituted Norbornadienes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 1044–1051. 10.1002/chin.200530075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Mayo P.; Tam W. Palladium-Catalyzed Hydrophenylation of Bicyclic Alkenes. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9527–9540. 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01277-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Yao Y.; Yang W.; Wang C.; Gu F.; Yang W.; Yang D. Radical Addition of Thiols to Oxa(Aza)Bicyclic Alkenes in Water. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 506–513. 10.1002/ajoc.201900033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Huang Y.; Smith K. B.; Brown M. K. Copper-Catalyzed Borylacylation of Activated Alkenes with Acid Chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 13314–13318. 10.1002/anie.201707323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Le Marquand P.; Tsui G. C.; Whitney J. C. C.; Tam W. Iron-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions between a Bicyclic Alkenyl Triflate and Grignard Reagents. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7829–7832. 10.1021/jo801384e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Cui M.; Oestreich M. Copper-Catalyzed Enantioselective and Exo-Selective Addition of Silicon Nucleophiles to 7-Oxa- And 7-Azabenzonorbornadiene Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2020, 21, 7244–7247. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hartline D. R.; Zeller M.; Uyeda C. Catalytic Carbonylative Rearrangement of Norbornadiene via Dinuclear Carbon-Carbon Oxidative Addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13672–13675. 10.1021/jacs.7b08691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lautens M.; Tam W.; Blackwell J. Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Diquinanes by the Regio- and Stereoselective Cleavage of Homo-Diels-Alder Cycloadducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 623–624. 10.1021/ja962223o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Forrest W. P.; Weis J. G.; John J. M.; Axtell J. C.; Simpson J. H.; Swager T. M.; Schrock R. R. Stereospecific Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Norbornadienes Employing Tungsten Oxo Alkylidene Initiators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10910–10913. 10.1021/ja506446n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tranmer G. K.; Tam W. Molybdenum-Mediated Cleavage Reactions of Isoxazoline Rings Fused in Bicyclic Frameworks. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4101–4104. 10.1021/ol026846k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Mayo P.; Tam W. Ring-Opening Metathesis-Cross-Metathesis Reactions (ROM-CM) of Substituted Norbornadienes and Norbornenes. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9513–9525. 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01276-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lautens M.; Klute W.; Tam W. Transition Metal-Mediated Cycloaddition Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 49–92. 10.1021/cr950016l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaglia A.; Marc S. CpRuCl(PPh3)2-Catalyzed Cyclopropanation of Bicyclic Alkenes with Tertiary Propargylic Acetates. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3569–3575. 10.1021/jo060276a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hu J.; Yang Q.; Yu L.; Xu J.; Liu S.; Huang C.; Wang L.; Zhou Y.; Fan B. A Study on the Substituent Effects of Norbornadiene Derivatives in Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric [2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2294–2301. 10.1039/c3ob27382b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fan B. M.; Li X. J.; Peng F. Z.; Zhang H.; Bin; Chan A. S. C.; Shao Z. H. Ligand-Controlled Enantioselective [2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Oxabicyclic Alkenes with Terminal Alkynes Using Chiral Iridium Catalysts. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 304–306. 10.1021/ol902574c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen J.; Xu X.; He Z.; Qin H.; Sun W.; Fan B. Nickel/Zinc Iodide Co-Catalytic Asymmetric [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Azabenzonorbornadienes with Terminal Alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 427–431. 10.1002/adsc.201701133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Lautens M.; Edwards L. G.; Tam W.; Lough A. J. Nickel-Catalyzed [2π + 2π + 2π] (Homo-Diels–Alder) and [2π + 2π] Cycloadditions of Bicyclo[2.2.1]Hepta-2,5-Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10276–10291. 10.1021/ja00146a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ricker J. D.; Geary L. M. Recent Advances in the Pauson–Khand Reaction. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 609–619. 10.1007/s11244-017-0741-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lledó A.; Benet-Buchholz J.; Solé A.; Olivella S.; Verdaguer X.; Riera A. Photochemical Rearrangements of Norbornadiene Pauson-Khand Cycloadducts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5943–5946. 10.1002/anie.200701658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cabot R.; Lledó A.; Revés M.; Riera A.; Verdaguer X. Kinetic Studies on the Cobalt-Catalyzed Norbornadiene Intermolecular Pauson-Khand Reaction. Organometallics 2007, 26, 1134–1142. 10.1021/om060935+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Rios R.; Pericàs M. A.; Moyano A.; Maestro M. A.; Mahía J. Reversing the Stereoselectivity of the Intermolecular Pauson-Khand Reaction: Formation of Endo-Fused Norbornadiene Adducts. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 1205–1208. 10.1021/ol025649i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Bernardes V.; Kann N.; Riera A.; Moyano A.; Pericàs M. A.; Greene A. E. Asymmetric Pauson—Khand Cyclization: A Formal Total Synthesis of Natural Brefeldin A. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6670–6671. 10.1021/jo00126a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tranmer G. K.; Tam W. Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of Norbornadiene-Tethered Nitrones. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 5113–5123. 10.1021/jo015610b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mayo P.; Hecnar T.; Tam W. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Nitrile Oxides with Unsymmetrically Substituted Norbornenes. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 5931–5941. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00573-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Chen W.; Yang W.; Wu R.; Yang D. Water-Promoted Synthesis of Fused Bicyclic Triazolines and Naphthols from Oxa(Aza)Bicyclic Alkenes and Transformation: Via a Novel Ring-Opening/Rearrangement Reaction. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2512–2518. 10.1039/C7GC03772D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Chen S.; Yao Y.; Yang W.; Lin Q.; Wang L.; Li H.; Chen D.; Tan Y.; Yang D. Three-Component Cycloaddition to Synthesize Aziridines and 1,2,3-Triazolines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 11863–11872. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b01713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kumaran S.; Saritha R.; Gurumurthy P.; Parthasarathy K. Synthesis of Fused Spiropyrrolidine Oxindoles Through 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Azomethine Ylides Prepared from Isatins and α-Amino Acids with Heterobicyclic Alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2725–2729. 10.1002/ejoc.202000247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu Y. T.; Linden A.; Siegel J. S. Formal [(2+2)+2] and [(2+2)+(2+2)] Nonconjugated Dienediyne Cascade Cycloadditions. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4353–4355. 10.1021/ol0514799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schrauzer G. N.; Glockner P. Über Die Katalytische Anlagerung von Olefinen Und Alkinen an Norbornadien Mit Ni0-Verbindungen Und Einem Neuen NiII-Komplex. Chem. Ber. 1964, 97, 2451–2462. 10.1002/cber.19640970908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wu Y. T.; Hayama T.; Baldridge K. K.; Linden A.; Siegel J. S. Synthesis of Fluoranthenes and Indenocorannulenes: Elucidation of Chiral Stereoisomers on the Basis of Static Molecular Bowls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6870–6884. 10.1021/ja058391a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach K.; Antropiusova H.; Petrusova L.; Hanus V.; Sedmera P. [6+2] Cycloadditions Catalyzed by Titanium Complexes. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 3295–3302. 10.1016/0040-4020(84)85014-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Padín D.; Varela J. A.; Saá C. Recent Advances in Ruthenium-Catalyzed Carbene/Alkyne Metathesis (CAM) Transformations. Synlett 2020, 31, 1147–1157. 10.1055/s-0039-1690861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Manikandan R.; Jeganmohan M. Recent Advances in the Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Chelation-Assisted C-H Olefination of Substituted Aromatics, Alkenes and Heteroaromatics with Alkenes via the Deprotonation Pathway. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8931–8947. 10.1039/C7CC03213G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ackermann L. Carboxylate-Assisted Ruthenium-Catalyzed Alkyne Annulations by C-H/Het-H Bond Functionalizations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 281–295. 10.1021/ar3002798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Nareddy P.; Jordan F.; Szostak M. Recent Developments in Ruthenium-Catalyzed C-H Arylation: Array of Mechanistic Manifolds. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5721–5745. 10.1021/acscatal.7b01645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Manikandan R.; Jeganmohan M. Recent Advances in the Ruthenium-Catalyzed Hydroarylation of Alkynes with Aromatics: Synthesis of Trisubstituted Alkenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10420–10436. 10.1039/C5OB01472G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Petko D.; Pounder A.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2+2] Bis-Homo-Diels-Alder Cycloadditions of 1,5-Cyclooctadiene with Alkynyl Phosphonates. Synthesis 2019, 51, 4271–4278. 10.1055/s-0039-1690612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Petko D.; Stratton M.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Bis-Homo-Diels-Alder Reaction: Searching for Commercially Available Catalysts and Expanding the Scope of Reaction. Can. J. Chem. 2018, 96, 1115–1121. 10.1139/cjc-2018-0117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kalaramna P.; Bhatt D.; Sharma H.; Goswami A. An Atom-Economical Approach to 2-Aryloxypyridines and 2,2′/2,3′-Diaryloxybipyridines via Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2+2] Cycloadditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 4379–4385. 10.1002/adsc.201900553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Rummelt S. M.; Radkowski K.; Roşca D. A.; Fürstner A. Interligand Interactions Dictate the Regioselectivity of Trans-Hydrometalations and Related Reactions Catalyzed by [Cp*RuCl]. Hydrogen Bonding to a Chloride Ligand as a Steering Principle in Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5506–5519. 10.1021/jacs.5b01475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guthertz A.; Leutzsch M.; Wolf L. M.; Gupta P.; Rummelt S. M.; Goddard R.; Farès C.; Thiel W.; Fürstner A. Half-Sandwich Ruthenium Carbene Complexes Link Trans-Hydrogenation and Gem-Hydrogenation of Internal Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3156–3169. 10.1021/jacs.8b00665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Aydemir M.; Baysal A. Cationic and Neutral Ruthenium(II) Complexes Containing Both Arene or Cp* and Functionalized Aminophosphines. Application to Hydrogenation of Aromatic Ketones. J. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 695, 2506–2511. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kondo T.; Kaneko Y.; Tsunawaki F.; Okada T.; Shiotsuki M.; Morisaki Y.; Mitsudo T. A. Novel Synthesis of Benzenepolycarboxylates by Ruthenium-Catalyzed Cross-Benzannulation of Acetylenedicarboxylates with Allylic Compounds. Organometallics 2002, 21, 4564–4567. 10.1021/om0205039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Villeneuve K.; Tam W. Construction of Isochromenes via a Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reaction of Oxabenzonorbornenes with Propargylic Alcohols. Organometallics 2007, 26, 6082–6090. 10.1021/om7004518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Matsui K.; Shibuya M.; Yamamoto Y. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Transfer Oxygenative [2 + 2 + 1] Cycloaddition of Silyldiynes Using Nitrones as Adjustable Oxygen Atom Donors. Synthesis of Bicyclic 2-Silylfurans. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6468–6472. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Yamashita K.; Yamamoto Y.; Nishiyama H. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Transfer Oxygenative Cyclization of α,ω-Diynes: Unprecedented [2 + 2 + 1] Route to Bicyclic Furans via Ruthenacyclopentatriene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7660–7663. 10.1021/ja302868s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Villeneuve K.; Tam W. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Cyclization of Oxabenzonorbornenes with Propargylic Alcohols: Formation of Isochromenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 24, 5449–5453. 10.1002/ejoc.200600836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Trost B. M.; Müller T. J. J.; Martinez J. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Butenolides and Pentenolides via Contra-Electronic α-Alkylation of Hydroxyalkynoates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 1888–1899. 10.1021/ja00112a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Trost B. M.; Müller T. J. J. Butenolide Synthesis Based upon a Contra-Electronic Addition in a Ruthenium-Catalyzed Alder Ene Reaction. Synthesis and Absolute Configuration of (+)-Ancepsenolide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 4985–4986. 10.1021/ja00090a053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Goodreid J.; Villeneuve K.; Carlson E.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Asymmetric [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between Chiral Acyl Camphorsultam-Substituted Alkynes and Bicyclic Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10002–10012. 10.1021/jo501594g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jordan R. W.; Tam W. Study on the Reactivity of the Alkene Component in Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between an Alkene and an Alkyne. Part 1. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2367–2370. 10.1021/ol016174i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jordan R. W.; Marquand Le.; Tam P. W. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions of Anti 7-Substituted Norbornenes. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 69, 8467–8474. 10.1021/jo048590x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Mitsudo T.-A.; Naruse H.; Kondo T.; Ozaki Y.; Watanabe Y. [2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Norbornenes with Alkynes Catalyzed by Ruthenium Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1994, 33, 580–581. 10.1002/anie.199405801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Jordan R. W.; Tam W. Reactivity of the Alkene Component in the Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloaddition between an Alkene and an Alkyne: Part 2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6051–6054. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Jordan R. W.; Khoury P. R.; Goddard J. D.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between 7-Substituted Norbornadienes and Alkynes: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 8467–8474. 10.1021/jo048590x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Burton R. R.; Tam W. Study on the Reactivity of Oxabicyclic Alkenes in Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7333–7336. 10.1021/jo701383d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Jordan R. W.; Villeneuve K.; Tam W. Study on the Reactivity of the Alkyne Component in Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between an Alkene and an Alkyne. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 5830–5833. 10.1021/jo060864o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Villeneuve K.; Jordan R. W.; Tam W. Diastereoselective Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions between Bicyclic Alkenes and a Chiral Propargylic Alcohol and Its Derivatives. Synlett 2003, 14, 2123–2128. 10.1055/s-2003-42108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Villeneuve K.; Riddell N.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Bicyclic Alkenes and Ynamides. Tetrahedron 2006, 7, 3681–3684. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Villeneuve K.; Tam W. Asymmetric Induction in Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions between Bicyclic Alkenes and a Chiral Acetylenic Acyl Sultam. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 610–613. 10.1002/anie.200352555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Villeneuve K.; Riddell N.; Jordan R. W.; Tsui G. C.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between Bicyclic Alkenes and Alkynyl Halides. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4543–4536. 10.1021/ol048111g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Cockburn N.; Karimi E.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Bicyclic Alkenes with Alkynyl Phosphonates. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5762–5765. 10.1021/jo9010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Riddell N.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions of Alkynyl Sulfides and Alkynyl Sulfones. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 1943–1937. 10.1021/jo052295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Allen A.; Villeneuve K.; Cockburn N.; Fatila E.; Riddell N.; Tam W. Alkynyl Halides in Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions of Bicyclic Alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 24, 4178–4192. 10.1002/ejoc.200800424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; p Villeneuve K.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Processes: Dual [2+2] Cycloaddition versus Cyclopropanation of Bicyclic Alkenes with Propargylic Alcohols. Organometallics 2006, 25, 843–848. 10.1021/om050780q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; q Burton R. R.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions between C1-Substituted 7-Oxanorbornadienes and Alkynes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7185–7189. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.07.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; r Tsui G. C.; Villeneuve K.; Carlson E.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between Norbornene and Propargylic Alcohols or Their Derivatives. Organometallics 2014, 33, 3847–3856. 10.1021/om500563h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; s Jack K.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Dimerization of 7-Oxabicyclo[2,2,1]Hepta-2,5-Diene-2,3- Dicarboxylates. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 3416–3420. 10.1021/jo400104q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; t Gulías M.; Collado A.; Trillo B.; López F.; Oñate E.; Esteruelas M. A.; Mascareñas J. L. Ruthenium-Catalyzed (2 + 2) Intramolecular Cycloaddition of Allenenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7660–7663. 10.1021/ja200784n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; u Tenaglia A.; Giordano L. CpRuCl(PPh3)2/MeI Catalyst System for the [2+2] Cycloaddition of Norbornenes with Disubstituted Alkynes. Synlett 2003, 15, 2333–2336. 10.1055/s-2003-42127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kettles T. J.; Cockburn N.; Tam W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Homo Diels-Alder [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Alkynyl Phosphonates with Bicyclo[2.2.1]Hepta-2,5-Diene. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6951–6957. 10.1021/jo2010928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams-Young D.; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A.; Peralta Jr. J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Hertwig R. H.; Koch W. On the Parameterization of the Local Correlation Functional. What Is Becke-3-LYP?. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 268, 345–351. 10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00207-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miehlich B.; Savin A.; Stoll H.; Preuss H. Results Obtained with the Correlation Energy Density Functionals of Becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 157, 200–206. 10.1016/0009-2614(89)87234-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Miertuš S.; Scrocco E.; Tomasi J. Electrostatic Interaction of a Solute with a Continuum. A Direct Utilizaion of AB Initio Molecular Potentials for the Prevision of Solvent Effects. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 117–129. 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Marenich A. V.; Kelly C. P.; Thompson J. D.; Hawkins G. D.; Chambers C. C.; Giesen D. J.; Winget P.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G.. Minnesota Solvation Database, version 2009; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, 2009.; b Winget P.; Dolney D. M.; Giesen D. J.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. J.. Minnesota Solvent Descriptor Database, version 1999; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, 1999.

- Legault C. Y.CYLview, 1.0b; Université de Sherbrooke: Canada, 2009. Http://www.Cylview.Org.

- a Liu P.; Jordan R. W.; Kibbee S. P.; Goddard J. D.; Tam W. Remote Substituent Effects in Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3793–3803. 10.1021/jo060103l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu P.; Tam W.; Goddard J. D. Ruthenium-Catalyzed [2+2] Cycloadditions between Substituted Alkynes and Norbornadiene: A Theoretical Study. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 7659–7666. 10.1016/j.tet.2007.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Trost B. M.; Toste F. D.; Pinkerton A. B. Non-Metathesis Ruthenium-Catalyzed C.-C. Bond Formation. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2067–2096. 10.1021/cr000666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Naota T.; Takaya H.; Murahashi S. I. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions for Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 2599–2660. 10.1021/cr9403695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; Imi K.; Indolese A. F. 1,5-Cyclooctadiene as a Bis-Homodiene Partner in a Metal-Catalyzed [4 + 2] Cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8831–8832. 10.1021/ja00072a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang X.; Lin Z. Density Functional Theory Studies of Ruthenium-Catalyzed Bis-Diels-Alder Cycloaddition of 1,5-Cyclooctadiene with Alkynes. Organometallics 2003, 22, 5478–5484. 10.1021/om0340591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang L.; Sung H. H. Y.; Williams I. D.; Lin Z.; Jia G. Reactions of Cp*RuCl(COD) with Alkynes: Isolation of Dinuclear Metallacyclopentatriene Complexes. Organometallics 2008, 27, 5122–5129. 10.1021/om8002202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaglia A.; Giordano L. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Homo-Diels–Alder Reactions of Disubstituted Alkynes and Norbornadiene. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 171–174. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.