Helminths modulate both whole body, and host macrophage metabolism and polarization. Metabolic changes underlie reprogramming of macrophage inflammatory responses.

Keywords: helminth, macrophage, metabolic disease, metabolism, schistosome

Summary

Macrophages are fundamental to sustain physiological equilibrium and to regulate the pathogenesis of parasitic and metabolic processes. The functional heterogeneity and immune responses of macrophages are shaped by cellular metabolism in response to the host’s intrinsic factors, environmental cues and other stimuli during disease. Parasite infections induce a complex cascade of cytokines and metabolites that profoundly remodel the metabolic status of macrophages. In particular, helminths polarize macrophages to an M2 state and induce a metabolic shift towards reliance on oxidative phosphorylation, lipid oxidation and amino acid metabolism. Accumulating data indicate that helminth‐induced activation and metabolic reprogramming of macrophages underlie improvement in overall whole‐body metabolism, denoted by improved insulin sensitivity, body mass in response to high‐fat diet and atherogenic index in mammals. This review aims to highlight the metabolic changes that occur in human and murine‐derived macrophages in response to helminth infections and helminth products, with particular interest in schistosomiasis and soil‐transmitted helminths.

Abbreviations

- AKG

α‐ketoglutarate

- Arg1

arginase 1

- BMDM

bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages

- C/EBPβ

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β

- CREB

cAMP response element‐binding protein

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- IL‐4

interleukin‐4

- ILC2

innate lymphoid type 2 cells

- M2

alternatively activated macrophage

- mTORC

mammalian target of rapamycin complex

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ

- SEA

schistosome egg antigens

- STAT‐6

signal transducer and activator of transcription 6

- STH

soil‐transmitted helminths

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- Th2

T helper type 2

- TLR

Toll‐like receptor

- TNF‐α

tumor necrosis factor α

Introduction: Perspectives of monocytes and macrophage heterogeneity

Monocytes are part of the mononuclear phagocytic system and are implicated in tissue homeostasis and several infectious and inflammatory processes. 1 Divergent functional capacities of monocytes are partly explained by the heterogeneity of the cellular subpopulations as evidenced by fate mapping, 2 unsupervised multi‐dimensional analysis, 3 transcriptional profiling analysis 4 , 5 and comprehensive proteomics. 6 In humans, monocytes were initially categorized according to their expression of CD14 (glycosylphosphatidylinositol‐anchored receptor) and CD16 (FcγRIII) antigens 7 in ‘classical’ (CD14++ CD16−) and ‘non‐classical’ (CD14+ CD16++) monocytes. 8 Classical monocytes exhibit a more phagocytic and pro‐inflammatory phenotype, whereas non‐classical monocytes are involved in patrolling and viral recognition. 9 Subsequent analyses further revealed an ‘intermediate’ subset (CD14+ CD16+). 10 , 11 ‘Intermediate’ monocytes are characterized as 6‐sulfo LacNAc‐negative, and express multiple surface expression markers that distinguish them from ‘non‐classical’ monocytes, which has been a topic of extensive revision. 12 , 13 , 14 Notably, each of the human subsets is not entirely homogeneous and presents rich intercellular variation and heterogeneity. 15

Monocytes in mice are characterized by their expression of CD115 (macrophage colony‐stimulating factor receptor), CD11b (integrin‐α M chain), and like their counterparts in humans, murine monocytes are also subdivided based on the expression of the surface marker Ly6C. Typically, ‘classical’ monocytes are described as Ly6C++ CD43− CCR2+ CD62L+ CX3CR1low and ‘non‐classical’ monocytes as Ly6C− CD43+ CCR2− CD62L− CX3CR1hi. 16 , 17 As in humans, GFP reporter CX3CR1 knock‐in mice showed a small population of intermediates monocytes. 18

Monocytes contribute many niches following the original seeding of tissue‐resident populations during embryonic development. 19 Relevant to regulation of the whole‐body metabolism, monocytes contribute to the macrophage niche in the self‐renewing arterial tissue, 20 in the expanding population of macrophages in the liver postnatally, in the fully differentiated Kupffer cells post‐depletion following a model of diphtheria toxin Clec4f‐specific depletion, 21 and replenish the macrophage pool in the intestine that persists into adulthood. 22 Moreover, during inflammation and in viral, 23 bacterial 24 and parasitic 25 infections, circulating monocytes aid in the expansion of macrophages in most tissues. In a mouse model of schistosomiasis, host‐protective macrophage proliferation was dependent on recruitment of Ly6Chi monocytes. 26 , 27 , 28

Like monocytes, macrophages exhibit marked heterogeneity depending on location and physiological requirements. 29 In their majority, tissue macrophages in the adult at steady‐state originate from the fetal liver and embryonic yolk sac precursors 30 , 31 , 32 that give rise to a specialized population that includes osteoclasts (bone), Kupffer cells (liver), perivascular macrophages (liver) and alveolar macrophages (lung) with a versatile transcriptome that bestows on them a distinguishable identity. 33 Within these diverse populations, macrophages exhibit great plasticity as a result of exposure to various stimuli, signaling molecules, nutrients and metabolites. 34 For example, phenotypical characterization of adipose tissue macrophages differs in lean and fatty adipose tissue in response to, at least in part, the availability of free fatty acids, lipoproteins and carbohydrates in the environment. 35 , 36 In lean adipose tissue, macrophages express CD206 and CD301 (markers of alternative activation), whereas macrophages express pro‐inflammatory inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) in obese adipose tissue. 37 The lung also possesses a heterogeneous macrophage population composed of alveolar macrophages, largely of embryonic origin, located principally in the airways, 38 and interstitial macrophages, located in the lung tissue and shown to be derived from circulating monocytes. 39 The role of localized tissue microenvironmental signals in murine macrophages has been demonstrated in vivo, where alveolar macrophages were less responsive to interleukin‐4 (IL‐4) at steady state, despite expressing normal IL‐4 receptor. However, dysregulated responsiveness to IL‐4 was restored when macrophages were removed from lung tissues, a process that was independent of commensals hosted in the lungs, pointing to an endogenous lung factor that regulates niche‐specific cell characteristics. 40 Interestingly, alveolar macrophages displayed reduced respiratory capacity and impaired glycolytic reserve and capacity. 40 Altogether, it is likely that with the continuous refinement of the ‘omics’ field more subpopulations of macrophages with defined plasticity and unique functional, transcriptional and metabolic fingerprints will be distinguished, enriching our understanding in how macrophages respond to stress and infections.

Metabolic programming of macrophages in homeostasis and upon activation

Metabolic profile and contributions of macrophages in equilibrium

M0 macrophages are resting or naive macrophages that have not been exposed to external stimulation. Metabolically, M0 macrophages resemble alternatively activated macrophages (M2) as they use an intact tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, where nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and flavine adenine dinucleotide from the TCA cycle are oxidized through a series of electron carriers and form ATP as the result of electron transfer. 41 In general, in steady‐state, oxidative phosphorylation maintains metabolic homeostasis and an optimal energy state. 42 In immunological steady‐state, tissue‐resident macrophages are responsible for maintenance of tissue integrity and stability, pathogen recognition and clearance. 43 , 44 , 45 Nevertheless, as the term ‘immunometabolism’ evolves, it becomes clearer that many of the functional capacities of immune cells are dependent on the metabolic state of the cell, and that in turn, some of the metabolic changes in the cell depend on external signals from the environment. In this section we explore some of the functions of macrophages associated with homeostatic balance when these cells have not been ‘primed’ or instructed by foreign signals and antigens. The sections hereafter will focus on metabolic and functional changes of macrophages upon recognition and activation by various parasite‐related signals.

As previously observed, macrophage identity can be shaped in response to different cues in compartmentalized tissues. 46 For example, the colony‐stimulating factor receptor 1 (CSFR‐1) pathway, via CSF‐1 and/or IL‐34, is required to maintain populations of steady‐state macrophages in liver, kidney, bone marrow and spleen. 47 In addition, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ), a bZIP transcription factor, 48 is required to maintain homeostatic numbers of functional large peritoneal macrophages and alveolar macrophages, but not splenic, skin or mesenteric macrophages in mice, 49 suggesting tissue‐specific heterogeneity in support of macrophage function. Indeed, the complexity of macrophage identity due to the richness of cellular diversity even within the same tissue is reflected in the diversity of transcriptional regulators and tissue‐specific genetic expression. 50 , 51 Just in the kidney, five discrete subpopulations have been identified 52 that express high levels of unique transcription factors such as aryl hydrocarbon receptor, nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 and 2, and interferon regulatory factor 9. 51 In the brain, a variety of transcription factors mediate transcriptional networks during development, steady‐state and disease. 53 Among these, MADS Box transcription enhancer factor 2, polypeptide c, interferon regulatory factor, Smad2/3 and Spalt like transcription factor 1 are key in microglia lineage determination. 53 In the liver, the transcription factor inhibitor of DNA binding 3 is essential for Kupffer cell development 54 whereas Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 1 Group H Member 3 maintains Kupffer cell identity. 55

In turn, in physiological conditions, macrophages are key to maintaining biological balance. A few examples of this phenomenon are observed in iron metabolism, where macrophages are the main cells that maintain iron balance and can act as ‘ferrostasts’ via regulation of iron levels in different tissue microenvironments. 43 Iron uptake by macrophages is mediated by transferrin receptor, divalent metal transporter 1, low‐density lipoprotein‐related receptor 1, hemoglobin–haptoglobin receptor (CD163) and natural‐resistance‐associated macrophage protein 1, which support iron uptake by erythrophagocytosis. 56 , 57 Once in the cytoplasm, iron is transported across the phagosomal membrane and ferric reductase and ferroxidases convert it to ferrous and ferric iron that will be exported through ferroportin, dependent on the systemic demand for iron. 58 , 59

By employing a combination of elegant fate mapping, bulk, and single‐cell RNA‐sequencing analyses, DeSchepper et al. 60 characterized a heterogenic population of self‐maintaining gut‐resident macrophages that sustain enteric neurons and submucosal blood‐vessel networks. Upon specific depletion of CX3CR1+ gut‐resident macrophages, physiological intestinal function, as well as anion secretion, electrical stimulation‐induced contractions and neuronal activity in the myenteric plexus were dampened in the mouse model when compared with mice not depleted of gut‐resident macrophages. Overall, these findings indicate that in healthy animals, macrophages are essential to maintain intestinal homeostasis and raise a potential role for tissue‐resident gut‐resident macrophages metabolic dysregulation in the development of metabolic disease. 61

Fundamentals of the metabolic programming of activated macrophages

Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages can be induced not only by the availability of different metabolic substrates like glucose or oxygen, but also by cytokine and antigenic signals. Currently, the nomenclature referring to the activation state of macrophages remains contentious, as many variables (macrophage origin and preparations, markers and stimuli) contribute to macrophage phenotypes. Nevertheless, an attempt to standardize the nomenclature and propose a common framework has been described by Murray et al., as well by Roszer. 62 , 63

The current paradigm states that M0 macrophages switch to M1 or classically activated macrophages in response to interferon‐γ and Toll‐like receptor (TLR) agonists that induce a metabolic shift, where M1 macrophages produce ATP through the pentose phosphate pathway, and an increased rate of glycolysis. In this state, M1 macrophages are characterized by expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, high levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines like TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐12 and IL‐23. 64 Moreover, recent CoMBI‐T pipeline approaches that combine mass spectrometry‐based metabolic analysis and RNA sequencing‐based transcriptional profiling has shown that M1 phenotype associates with a truncated TCA cycle at the isocitrate‐to‐oxoglutarate (AKG) step and an increased ratio of (iso)citrate to AKG. 65

In contrast, M2 (alternatively activated) macrophages display enhanced oxidative phosphorylation, purine synthesis, arginine metabolism and a dependence on glutamine to sustain M2 commitment. 65 This metabolic state correlates with an immune phenotype characterized by up‐regulation of arginase‐1 (Arg1), chitinase‐3‐like protein 3, C‐type mannose receptor 1 (CD206), found in resistin‐like α (Retnla) and galactose‐type C‐type lectin (CD301) in mice. 66 , 67 In humans, polarization of macrophages by the definition of M2 macrophages is less clear, but IL‐4 or IL‐13 has been shown to increase expression of CD209, CD200R, CD1a and CD1b. 68 Induction of an alternatively activated state requires oxidative metabolism, as elegant studies by Vats et al. showed that inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and fatty acid oxidation reduced M2‐related markers like Arg1 in a signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT‐6) and peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ (PPARγ) coactivator 1β‐(PGC‐1β) dependent fashion. 69 Moreover, M2 macrophages have been subcategorized into M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d. M2a are induced by IL‐4 and IL‐13, express Arg1, CD206, Retnla (FIZZ1) and transforming growth factor‐β, and are associated with wound healing and both protective and pathogenic roles in asthma, by inducing allergen clearance mediated by MRC1 and eosinophilic inflammation by TGM2, respectively. 63 , 70 , 71 Recently, Wang et al. have shown that when both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis are inhibited by 2‐Deoxy‐D‐glucose, macrophages fail to differentiate to M2a. 72 Nevertheless, when oxidative phosphorylation remains active, glycolysis is not required to maintain M2a differentiation, underscoring the plasticity of macrophages under different metabolic circumstances. M2b macrophages are stimulated by immune complexes, TLR ligands such as lipopolysaccharide and IL‐1β, secrete IL‐10, CCL1, IL‐6 and TNF‐α, and display angiogenic potential. 73 Recently, M2b polarization induced by Schistosoma japonicum egg antigens was shown to depend on nuclelar factor‐κB signaling via the MyD88/mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathway and TLR2. 74 Moreover, M2b macrophages are essential for granuloma regulation during Schistosoma mansoni infection. 75 M2c macrophages become activated by glucocorticoids and IL‐10, have high expression levels of CD86, MHCII, mer receptor tyrosine kinase and haptoglobin‐hemoglobin scavenger receptor (CD163) and are implicated in tissue repair via extracellular matrix remodeling. 76 M2d macrophages, also identified as tumor‐associated macrophages, can be activated by TLR ligands, A2 adenosine receptor agonists, leukemia inhibitory factor and IL‐6. 77 , 78 They secrete epidermal growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor and several cytokine mediators such as IL‐10, transforming growth factor‐β, IL‐12 and TNF‐α, thereby contributing to angiogenesis, tumor growth and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Overall, recent analysis of the metabolic modulation of each of these subtypes following polarization of human CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells suggests a shared increase in fatty acid oxidation (FAO), supported by a decreased carnitine in M2b and up‐regulation of fatty acid‐binding protein 4 and lipoprotein lipase in M2a macrophages. Moreover, metabolite profiling using metabolic pathway topology showed a significant role for amino acid metabolism in each of the subsets, as the β‐alanine pathway was identified as highly impacted following polarization to the M2a, M2b and M2d phenotypes, which is consistent with previous reports that have showed β‐alanine metabolism altered, as a by‐product of increased arginine metabolism in anti‐inflammatory macrophages. 79 , 80 Importantly, despite many efforts to define macrophage subpopulations in both mice and humans, these classifications are largely limited to in vitro settings and extensive in vivo characterizations are still lacking. 63

Host immunomodulation during helminth infection

Helminths are clinically relevant invertebrates comprising trematodes, also referred to as flukes, that are leaf‐shaped flatworms; cestodes or tapeworms that are elongated flatworms; and nematodes or roundworms that are cylinder‐shaped worms. Rates of infection are typically high in tropical and subtropical areas of the world where helminths are endemic, with 24% of the population, or 1·5 billion people, affected. 81 Although not typically associated with high mortality, they cause high morbidity, due in part to the parasite’s ability to survive and thrive in the host for decades, leading to chronic disease that often goes unnoticed and untreated. 82 , 83 , 84 Consequently, helminthiasis has been correlated with long‐lasting pathologies such as anemia, undernutrition, periportal fibrosis and hypertension, and impairment of cognitive development that translates into serious disease burden and high disability‐adjusted life‐years, 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 which accounts for the burden of the disease and represents the number of years of life lost through premature mortality or disability. 89

The chronicity of helminth infections is partially explained by the parasite’s ability to manipulate and dampen the host immune responses. In brief, helminths target pattern recognition receptors and can down‐regulate TLRs and other genes associated with inflammatory responses. Hartgers et al. found that down‐regulation of TLR2 was associated with Schistosoma haematobium in school children in Ghana who showed less atopic allergic reactivity. 90 Further, helminths also suppress initiating alarmin signals like IL‐33 91 , 92 and the inflammasome system. 93 , 94 Indeed, helminths induce strong type 2 activation and alternative activation of macrophages characterized by the production of IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐9, IL‐10 and IL‐13. 95 , 96 Nevertheless, given the complexity of these organisms, the immune response and activation profiles of macrophages are divergent and depend in part on the tissues that individual species migrate through in the host, as well excretory/secretory factors directly secreted by the helminths. Added to this, macrophage responses are dependent on their cellular lineage, 97 the susceptibility of the genetic background 98 and sex differences of the host. 99

Mounting epidemiological evidence shows that helminth infections inversely correlate with many autoimmune, inflammatory and, importantly, metabolic diseases. 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 This evidence warrants studying these parasitic organisms and their individual roles in host immunomodulation, and the potential of parasite‐derived products in diverse therapeutics. 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111

Macrophage immunometabolism in Schistosoma and soil‐transmitted helminths

Metabolic regulation of macrophages in Schistosoma infection

Schistosomiasis is caused by infection with trematode parasites of the genus Schistosoma and affects over 200 million people in 74 countries. 112 Among the species with most clinical relevance in human diseases are S. mansoni, S. haematobium and S. japonicum. 113 In the host, schistosomes induce a potent T helper type 2 (Th2) ‐biased immune response and polarization of macrophages to a broad M2 phenotype, which is vital for host survival. 114 , 115 Interestingly, multiple epidemiological studies have observed an inverse correlation between both active infection and a previous history of schistosome infection and metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes, raising interest in the metabolic reprogramming that schistosomes induce in diverse cells of the immune system. 105 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 As one of the major players in the pathology of disease, macrophages modulate initiation and disease resolution in schistosomiasis. 120 In recent years, it has become apparent that metabolic processes can regulate immune responses, and it is likely that appropriate responses to the disease require a partnership between metabolic and immunological pathways. Hence, this section focuses on the metabolic modulation that is induced by schistosome infection and schistosome products on organ‐specific populations of macrophages.

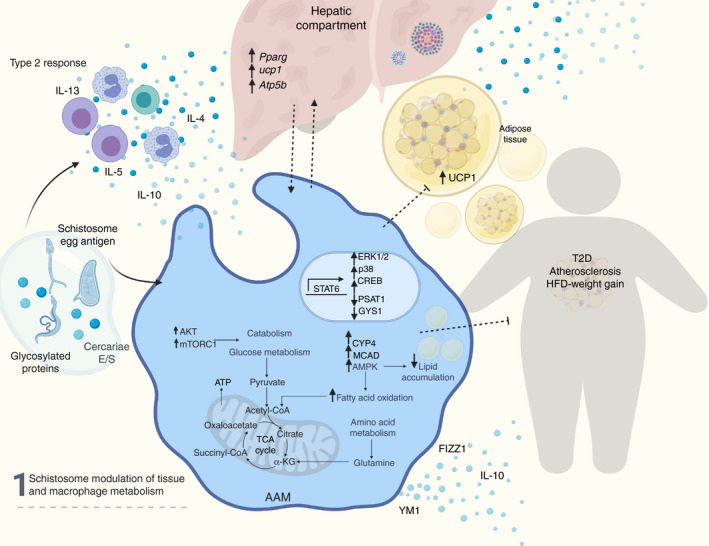

Recently, the kinetics of the expression of genes associated with hepatic lipid metabolism during S. japonicum infection showed that the PPARγ was dynamically regulated in the hepatic compartment following infection, and that its mRNA levels were significantly up‐regulated after 4 weeks of infection. 121 Previously, PPARγ was identified as a link between macrophage alternative activation and glutamine metabolism. 122 PPARγ is necessary for induction of an M2 phenotype and is inducible by IL‐4. 123 , 124 Schistosomes have recently been shown to produce the lipid lysophosphatidylcholine, which is able to induce M2 activation in a PPARγ‐dependent manner 125 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schistosome modulation of tissue and macrophage metabolism. Schistosome‐derived products induce a type‐2 response with secretion of interleukin‐4 (IL‐4), IL‐13, IL‐5, IL‐10 cytokines by eosinophils and lymphocytes. Concomitantly, schistosome products are recognized by pattern recognition receptors in macrophages and induce an alternative activated phenotype, dependent on the signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT‐6), and reprogramming of metabolism‐related genes. Alternative activation by schistosomes up‐regulates fatty acid oxidation and attenuates lipid accumulation. Up‐regulation of AKT and mTORC1 modulates catabolism and glucose metabolism. Additionally, schistosome‐induce macrophage reprogramming contributes to the metabolic regulation of hepatic and adipose tissue and the protection from high‐fat diet induced weight gain, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis. AKT, protein kinase B; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1.

Consistent with alternative activation, mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2, relevant for lowering mitochondrial membrane potential and maintaining respiration, 126 , 127 is up‐regulated in the acute stage of infection. 121 In addition, the modulation of macrophage metabolism does not seem to be limited to active infection as in vitro analysis has shown that Schistosoma egg antigen (SEA), a soluble mixture of highly glycosylated proteins that acts as a potent immunomodulator, 128 can increase the functional activity of 5' AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK), protein kinase B (AKT) and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), so supporting glucose metabolism in macrophages 128 (Fig. 1). Moreover, SEA treatment decreased lipid accumulation in macrophages in a phosphorylated‐AMPK‐dependent manner. 121 Similarly, Qian et al. found that SEA up‐regulates the expression of genes associated with lipid oxidation in macrophages. 129 However, among the essential genes modulated by the parasite antigen they found medium‐chain acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase and Cytochrome P450 protein 4 to be significantly increased. Further, phosphatase and tensin homolog, a tumor suppressor gene involved in enhanced oxidative phosphorylation and decreased glycolysis, 130 was down‐modulated in response to exposure to SEA, thereby suggesting that SEA induces reprogramming of glucose and lipid metabolism. These data indicate a role for phosphatase and tensin homologue in the reprogramming of macrophages following parasite antigen exposure. 129

In addition to the effects mediated by schistosome egg antigens, the excretory and secretory products of S. mansoni cercariae, which are free‐swimming larvae that are the infective stage of the parasite in mammals, 131 also drive the production of IL‐10 and in turn rapidly trigger ERK1/2, p38 and cAMP response element‐binding protein (CREB) activation in bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages in a TLR2‐ and TLR4‐dependent fashion. Consequently, CREB activation results in transcriptional regulation of a series of genes involved in metabolic processes, including glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation and protein ubiquitination. 132

Changes in the catabolic metabolism of the murine host’s spleen have been observed during acute infection with S. mansoni. Several pathways related to the TCA cycle, respiratory transport and amino acid metabolism were differentially expressed in infected mice at the peak of the acute phase as determined by a large‐scale, label‐free shotgun proteomics approach, with many of these alterations attributable to macrophages, highlighting the impact of schistosome infection on the metabolic modulation of organ‐specific macrophage populations. 133

Active infection with S. mansoni also results in metabolic reprogramming of two subpopulations of liver macrophages (perivascular macrophages and Kupffer cells) in a model of atherogenesis‐prone mice (ApoE−/−) on a high‐fat diet, where infection improves glucose sensitivity, circulating cholesterol levels and body mass index in vivo. Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages coincided with an M2 phenotype (CD301+ CD206+) and was characterized by regulation of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis, such as Psat1, as well as genes involved in glycogen synthesis like Gys1. 134 These data might suggest that macrophage‐specific metabolic regulation mediated by schistosome infection can affect overall systemic metabolism, underscoring the importance of understanding helminth metabolic regulation of macrophages 134 (Fig. 1). Recent data suggest that schistosome‐induced metabolic modulation may be sex dependent. Infection in male ApoE−/− mice improves glucose tolerance, diet‐induced obesity and triglycerides, but this does not occur in female mice. Interestingly, infection induces an increase in spare respiratory capacity and mitochondrial biogenesis in bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMDM) from infected male mice, but this does not occur in BMDM from infected female mice. Moreover, analysis of the lipidomic profile of BMDM from male mice indicates that infection induces a reduction in cellular cholesterol esters, with a concomitant increase in shuttling of glucose and palmitate to the TCA cycle, 135 which supports the idea of an infection‐ and sex‐dependent increase in mitochondrial β‐oxidation. Critically, the presence of these modulations in unstimulated BMDM indicates that metabolic reprogramming occurs in the bone marrow myeloid pool in the context of infection. Collectively, these studies also show that schistosomes induce profound changes in amino acid metabolism. Glutamine accumulation is a feature of M2 macrophages, and glutamine promotes polarization through a glutaminolysis‐derived α‐ketoglutarate‐dependent pathway that also inhibits M1 polarization by suppressing the nuclear factor‐κB pathway. 136 To date, in the context of metabolic profiling, females have been studied in relatively few human or murine helminth models, so it is unclear if this is specific to schistosomiasis, but there are known sex‐dependent dimorphisms in the susceptibility and pathology of metabolic disorders. 137 , 138 , 139 Notably, dimorphism in the susceptibility to helminth infections has been described by Wedekind and Jakobsen, who found that males were more likely to be infected and to have higher parasite numbers than females in an experimental model. 140

Among S. mansoni‐specific molecules, ω1 plays a dominant role in type 2 activation 141 , 142 and in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. 143 While ω1 does not directly activate macrophages, a mechanism dependent on its T2 RNase activity induces binding to CD206, so triggering other innate cells to secrete IL‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐13 to polarize macrophages to an alternative activation state. 143

Interleukin‐4‐induced alternative activation has previously been shown to be dependent on both FAO via cell intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis, and mTORC2‐dependent up‐regulation of glycolysis. 144 , 145 It has recently been demonstrated that mitochondrial FAO is higher in human adipose‐associated macrophages than in adipocytes, and that enhancing mitochondrial FAO in a model of type 2 diabetes reduces triglyceride content and inflammation. 146 These data support the idea that during schistosome infection, reprogramming of macrophages could underlie whole‐body metabolic changes. Although it is not clear how schistosome products induce metabolic modulation in human macrophages, new more sensitive tools to study cellular metabolism will allow an in‐depth analysis to help dissect the contributions of these complex metabolic pathways to the biology of infection in humans. Many questions remain regarding the evolutionary advantages that these switches provide to helminths in general and schistosomes in particular.

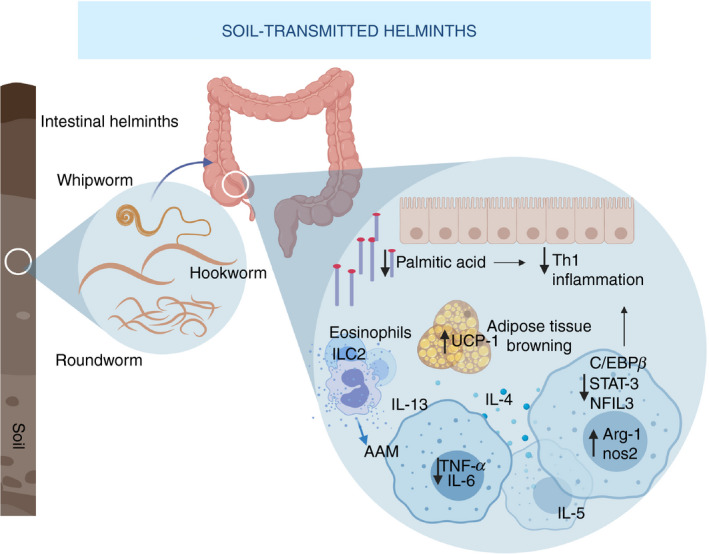

Effect of soil‐transmitted helminths on metabolism

Soil‐transmitted helminths (STH) are also known for their immunomodulatory properties. Infections with Ascaris lumbricoides, Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus, Strongyloides stercoralis and Trichuris sp. (collectively known as soil‐transmitted helminths) elicit a potent Th2 response and correlate with enhanced insulin sensitivity and improved metabolic index in both human populations and mouse models. 147 , 148 , 149 The effects of STH on metabolic disease are, to some extent, explained by regulation of metabolic homeostasis by IL‐4‐competent eosinophils in adipose tissue 150 and reduced Th1 inflammation, 151 , 152 which is partially due to regulation of fatty acid metabolism by STH. 153 For example, infection with Strongyloides venezuelensis, the murine analogue of S. stercoralis, lowers palmitic acid in the intestine of infected mice on a high‐fat diet, 153 thereby counteracting the TLR4‐dependent indirect induction of inflammation by palmitic acid. 154 , 155 Moreover, human infection with S. stercoralis is associated with lower circulating Th1 cytokines, insulin, glucagon, and the hormones adiponectin and adipsin (required for fatty acid breakdown and regulation of glucose and β‐cell functions), all of which showed a reversal following antihelminthic treatment. 156 Similar to schistosomes, most of the STH produce antigens that induce an alternatively activated phenotype in macrophages, 157 which is necessary to contribute to the expulsion of the intestinal parasites and wound repair. 156 , 158 , 159 In the case of Trichuris suis, excretory/secretory products by themselves induce Arg1 and nitric oxide synthase 2 expression in BMDM, which highlights the phenotypic heterogeneity of macrophages in vivo and probably reflects an immunosuppressive state rather than an M2 phenotype. Additionally, T. suis recombinant proteins such as nucleoside diphosphate kinase and triosephosphate isomerase inhibit TNF‐α expression and induce phosphorylation of STAT‐3 and expression of transcriptions factors that drive anti‐inflammatory processes (such as C/EBPβ and nuclear factor IL‐3‐regulated 3) in BMDM. 160 Like schistosomiasis, changes in the activation phenotype of macrophages in response to STH also correlates with regulation of metabolic disease. 161 For instance, infection with the murine intestinal parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri polarized macrophages to an M2 phenotype, that when transferred to uninfected recipients receiving a high‐fat diet, induced tissue browning and uncoupling protein 1 protein levels in adipose tissue, which was accompanied by ameliorated levels of glucose, fat, cholesterol level, leptin and TNF‐α. 161 The maintenance of the M2 phenotype requires populations of both eosinophils and innate lymphoid type 2 cells (ILC2) that produce IL‐4 and IL‐13 and are localized in perigonadal and other areas of visceral adipose tissue, as depletion of both cell populations is linked to reduced Arg1 expression in murine adipose alternative activated macrophages 162 (Fig. 2). Using the murine Nippostrongylus brasiliensis model of STH, Yang et al. have recently shown that infection reverses high‐fat‐diet‐induced adipose mass gains, hepatic steatosis and liver triglycerides, while restoring glucose homeostasis. These protections correlate with the accumulation of M2 macrophages in the epididymal fat, a process that is only partially dependent on IL‐13 and STAT6, 163 suggesting that metabolic modulation is not simply driven by alternative activation, but may also be driven directly by parasite antigens. Expansion of IL‐4‐ and IL‐13‐expressing ILC2 following helminth infection 164 highlights the ability of these parasites to orchestrate a systemic response that shapes diverse tissue compartments as well as key cellular players, which results in systemic metabolic regulation (Fig. 2). As our knowledge of immunometabolism and its regulation by intestinal parasites grows, it is likely that processes that influence systemic metabolism will come to light that are distinct from what has been detailed in response to schistosome infection. In particular, data revealing changes in the microbiota as a result of intestinal helminth infections and disruption in the metabolome of the intestine 165 , 166 , 167 that results in improved insulin sensitivity 153 add another layer of complexity to the understanding of the impact of STH on the immunometabolism of diverse organs and immune cells.

Figure 2.

Soil‐transmitted helminths (STH) and regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Intestinal helminths such as roundworms, whipworms and hookworm lodge in the colon and cecum, elicit a strong type 2 response, and reduce T helper type 1 inflammation by lowering fatty acids in the intestine of infected mammals. Moreover, they induce polarization of macrophages to an alternative activated phenotype, characterized by Arg‐1 and Nos‐2 up‐regulation, downmodulation of pro‐inflammatory factors like IL‐6, TNF‐α, STAT‐3, C/EBPβ, and NFIL3 and secretion of IL‐4, IL‐13 and IL‐5 in macrophages, eosinophils and innate lymphoid cells 2 (ILC2). Infection by STH contributes to changes in the adipose compartment and adipose tissue browning, mediated in part by UCP‐1, which correlates to reduced fat and cholesterol levels and overall improved metabolic index in humans. Arg‐1, arginase‐1; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; Nos‐2, Nitric oxide synthase 2; STAT‐3, signal transducer and activator 3; C/EBPβ, CCAAT‐enhancer‐binding protein; NFIL3, Nuclear Factor, IL‐3 Regulated; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Concluding remarks

Over the past decade, a combination of cross‐sectional studies in populations endemic for parasitic helminths, and animal models have demonstrated that both active infection and treatment with helminth antigens such as SEA 119 can improve parameters of whole‐body glucose homeostasis, obesity and cholesterol metabolism. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, but most revolve around the generation of type 2 immunity in innate lymphocytes (macrophages 137 , ILC2 119 , 143 , eosinophils 122 ) recruited to metabolic tissues such as the liver and white adipose tissue (Figs 1 and 2). It is most probable that all of these cell types work in concert with the microbiota to orchestrate metabolic homeostasis in the context of helminth infection, as well as during ideal lean conditions. In the case of macrophages, there is compelling data that helminth‐polarized macrophages alone are able to modulate whole‐body metabolism, and that helminth antigens are able to modulate metabolism via IL‐33 induction 143 and independently of IL‐13 and STAT‐6. 163 However, the relative contributions of cytokines versus helminth antigens and the mechanistic role of each innate cell type in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism remain to be fully elucidated (see Outstanding Questions). As such, it is critically important to identify both new molecular pathways modulated by helminths, as well as novel modulatory helminth antigens capable of inducing whole‐body metabolic reprogramming.

Outstanding Questions in the Field.

What is the relative contribution of macrophages to the metabolic profile of metabolic organs such as liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, pancreas? Are the molecular mechanisms driving cellular metabolism the same in each compartment?

What is the dominant driver of re‐programming of macrophage and other innate cells metabolism: cytokines or helminth antigens?

What role does biological sex play in metabolic re‐programming by helminths? Are there sex‐dependent effects in other innate cells such as ILC2 and eosinophils during schistosomiasis? Is there sexual dimorphism in the metabolic protection induced by various STH?

How long lived is myeloid and whole‐body metabolic re‐programming in the absence of ongoing infection?

Does the type‐2 induced metabolic re‐programming of murine innate lymphocytes recapitulate in humans? Is reprogramming tissue specific, or does it extend to monocytes and myeloid progenitors?

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests. Diane Cortes‐Selva is currently and employee of Janssen Biotherapeutics.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was written by DCS and KCF. This work was supported by University of Utah, National Institutes of Health, NIAID, R01 (AI135045) to KCF, and an American Heart Association Pre‐doctoral Award (18PRE34030086) to DCS. We thank Lisa Gibbs for editorial assistance.

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS REVIEW SERIES

Sweet talk: Metabolic conversations between host and microbe during infection. Immunology 2021, 162: 121‐122.

Targeting metabolism to reverse T‐cell exhaustion in chronic viral infections. Immunology 2021, 162: 135‐144.

Targeting immunometabolism in host defence against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunology 2021, 162: 145‐159.

References

- 1. Rahman MS, Murphy AJ, Woollard KJ. Effects of dyslipidaemia on monocyte production and function in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017; 14:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M et al Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 2013; 38:79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merah‐Mourah F, Cohen SO, Charron D, Mooney N, Haziot A. Identification of novel human monocyte subsets and evidence for phenotypic groups defined by interindividual variations of expression of adhesion molecules. Sci Rep 2020; 10:4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ancuta P, Liu KY, Misra V, Wacleche VS, Gosselin A, Zhou X et al Transcriptional profiling reveals developmental relationship and distinct biological functions of CD16+ and CD16– monocyte subsets. BMC Genom 2009; 10:403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R et al Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood 2010; 115:e10–e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravenhill BJ, Soday L, Houghton J, Antrobus R, Weekes MP. Comprehensive cell surface proteomics defines markers of classical, intermediate and non‐classical monocytes. Sci Rep 2020; 10:4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler‐Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood 1989; 74:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narasimhan PB, Marcovecchio P, Hamers AAJ, Hedrick CC. Nonclassical monocytes in health and disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2019; 37:439–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B et al Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity 2010; 33:375–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grage‐Griebenow E, Zawatzky R, Kahlert H, Brade L, Flad H, Ernst M. Identification of a novel dendritic cell‐like subset of CD64+/CD16+ blood monocytes. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, Rotter B, Winter P, Marell RR, Fliser D et al SuperSAGE evidence for CD14++CD16+ monocytes as a third monocyte subset. Blood 2011; 118:e50–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sampath P, Moideen K, Ranganathan UD, Bethunaickan R. Monocyte subsets: phenotypes and function in tuberculosis infection. Front Immunol 2018; 9:1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tacke F, Randolph GJ. Migratory fate and differentiation of blood monocyte subsets. Immunobiology 2006; 211:609–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kapellos TS, Bonaguro L, Gemund I, Reusch N, Saglam A, Hinkley ER et al Human monocyte subsets and phenotypes in major chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 2019; 10:2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gren ST, Rasmussen TB, Janciauskiene S, Håkansson K, Gerwien JG, Grip O. A single‐cell gene‐expression profile reveals inter‐cellular heterogeneity within human monocyte subsets. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0144351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ziegler‐Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN et al Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 2010; 116:e74–e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 2003; 19:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qu C, Edwards EW, Tacke F, Angeli V, Llodra J, Sanchez‐Schmitz G et al Role of CCR8 and other chemokine pathways in the migration of monocyte‐derived dendritic cells to lymph nodes. J Exp Med 2004; 200:1231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bain CC, Hawley CA, Garner H, Scott CL, Schridde A, Steers NJ et al Long‐lived self‐renewing bone marrow‐derived macrophages displace embryo‐derived cells to inhabit adult serous cavities. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ensan S, Li A, Besla R, Degousee N, Cosme J, Roufaiel M et al Self‐renewing resident arterial macrophages arise from embryonic CX3CR1+ precursors and circulating monocytes immediately after birth. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scott CL, Zheng F, De Baetselier P, Martens L, Saeys Y, De Prijck S et al Bone marrow‐derived monocytes give rise to self‐renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat Commun 2016; 7:10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bain CC, Bravo‐Blas A, Scott CL, Perdiguero EG, Geissmann F, Henri S et al Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:929–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Getts DR, Terry RL, Getts MT, Muller M, Rana S, Shrestha B et al Ly6c+ "inflammatory monocytes" are microglial precursors recruited in a pathogenic manner in West Nile virus encephalitis. J Exp Med 2008; 205:2319–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krutzik SR, Tan B, Li H, Ochoa MT, Liu PT, Sharfstein SE et al TLR activation triggers the rapid differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat Med 2005; 11:653–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mordue DG, Sibley LD. A novel population of Gr‐1+‐activated macrophages induced during acute toxoplasmosis. J Leukoc Biol 2003; 74:1015–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nascimento M, Huang SC, Smith A, Everts B, Lam W, Bassity E et al Ly6Chi monocyte recruitment is responsible for Th2 associated host‐protective macrophage accumulation in liver inflammation due to schistosomiasis. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Girgis NM, Gundra UM, Ward LN, Cabrera M, Frevert U, Loke P. Ly6Chigh monocytes become alternatively activated macrophages in schistosome granulomas with help from CD4+ cells. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rolot M, Dougall AM, Javaux J, Lallemand F, Machiels B, Martinive P et al Recruitment of hepatic macrophages from monocytes is independent of IL‐4Rα but is associated with ablation of resident macrophages in schistosomiasis. Eur J Immunol 2019; 49:1067–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue‐specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell 2014; 157:832–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L et al Tissue‐resident macrophages originate from yolk‐sac‐derived erythro‐myeloid progenitors. Nature 2015; 518:547–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoeffel G, Chen J, Lavin Y, Low D, Almeida FF, See P et al C‐Myb+ erythro‐myeloid progenitor‐derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue‐resident macrophages. Immunity 2015; 42:665–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most tissue‐resident macrophages except microglia are derived from fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity 2015; 43:382–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S et al Gene‐expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:1118–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sakai M, Troutman TD, Seidman JS, Ouyang Z, Spann NJ, Abe Y et al Liver‐derived signals sequentially reprogram myeloid enhancers to initiate and maintain Kupffer cell identity. Immunity 2019; 51:655–70. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Daemen S, Schilling JD. The interplay between tissue niche and macrophage cellular metabolism in obesity. Front Immunol 2020; 10:3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Serbulea V, Upchurch CM, Schappe MS, Voigt P, DeWeese DE, Desai BN et al Macrophage phenotype and bioenergetics are controlled by oxidized phospholipids identified in lean and obese adipose tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115:E6254–E6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lumeng CN, DelProposto JB, Westcott DJ, Saltiel AR. Phenotypic switching of adipose tissue macrophages with obesity is generated by spatiotemporal differences in macrophage subtypes. Diabetes 2008; 57:3239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guilliams M, De Kleer I, Henri S, Post S, Vanhoutte L, De Prijck S et al Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long‐lived cells in the first week of life via GM‐CSF. J Exp Med 2013; 210:1977–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gibbings SL, Thomas SM, Atif SM, McCubbrey AL, Desch AN, Danhorn T et al Three unique interstitial macrophages in the murine lung at steady state. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2017; 57:66–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Svedberg FR, Brown SL, Krauss MZ, Campbell L, Sharpe C, Clausen M et al The lung environment controls alveolar macrophage metabolism and responsiveness in type 2 inflammation. Nat Immunol 2019; 20:571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koo SJ, Garg NJ. Metabolic programming of macrophage functions and pathogens control. Redox Biol 2019; 24:101198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilson DF. Programming and regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015; 308:E506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Winn NC, Volk KM, Hasty AH. Regulation of tissue iron homeostasis: the macrophage “ferrostat”. JCI Insight 2020; 5:e132964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue‐resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity 2016; 44:439–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bain CC, Mowat AM. Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Immunol Rev 2014; 260:102–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin W, Xu D, Austin CD, Caplazi P, Senger K, Sun Y et al Function of CSF1 and IL34 in macrophage homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer. Front Immunol 2019; 10:2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wedel A, Ziegler‐Heitbrock HW. The C/EBP family of transcription factors. Immunobiology 1995; 193:171–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cain DW, O'Koren EG, Kan MJ, Womble M, Sempowski GD, Hopper K et al Identification of a tissue‐specific, C/EBPβ‐dependent pathway of differentiation for murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol 2013; 191:4665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Munro DAD, Hughes J. The origins and functions of tissue‐resident macrophages in kidney development. Front Physiol 2017; 8:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mass E, Ballesteros I, Farlik M, Halbritter F, Gunther P, Crozet L et al Specification of tissue‐resident macrophages during organogenesis. Science. 2016; 353:aaf4238 10.1126/science.aaf4238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kawakami T, Lichtnekert J, Thompson LJ, Karna P, Bouabe H, Hohl TM et al Resident renal mononuclear phagocytes comprise five discrete populations with distinct phenotypes and functions. J Immunol 2013; 191:3358–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yeh H, Ikezu T. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of microglia in health and disease. Trends Mol Med 2019; 25:96–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2017; 17:306–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scott CL, T'Jonck W, Martens L, Todorov H, Sichien D, Soen B et al The transcription factor ZEB2 is required to maintain the tissue‐specific identities of macrophages. Immunity 2018; 49:312–25. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Soe‐Lin S, Sheftel AD, Wasyluk B, Ponka P. Nramp1 equips macrophages for efficient iron recycling. Exp Hematol 2008; 36:929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sukhbaatar N, Weichhart T. Iron regulation: macrophages in control. Pharmaceuticals 2018; 11:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shi H, Bencze KZ, Stemmler TL, Philpott CC. A cytosolic iron chaperone that delivers iron to ferritin. Science 2008; 320:1207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Delaby C, Pilard N, Goncalves AS, Beaumont C, Canonne‐Hergaux F. Presence of the iron exporter ferroportin at the plasma membrane of macrophages is enhanced by iron loading and down‐regulated by hepcidin. Blood 2005; 106:3979–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. De Schepper S, Verheijden S, Aguilera‐Lizarraga J, Viola MF, Boesmans W, Stakenborg N et al Self‐maintaining gut macrophages are essential for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 2018; 175:400–15. e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Winer DA, Winer S, Dranse HJ, Lam TK. Immunologic impact of the intestine in metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017; 127:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S et al Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 2014; 41:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roszer T. Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm 2015; 2015:816460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Atri C, Guerfali FZ, Laouini D. Role of human macrophage polarization in inflammation during infectious diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19:1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E et al Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 2015; 42:419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, Ruiz‐Rosado Jde D, Popovich PG, Partida‐Sanchez S et al Novel markers to delineate murine M1 and M2 macrophages. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0145342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yu T, Gan S, Zhu Q, Dai D, Li N, Wang H et al Modulation of M2 macrophage polarization by the crosstalk between Stat6 and Trim24. Nat Commun 2019; 10:4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tarique AA, Logan J, Thomas E, Holt PG, Sly PD, Fantino E. Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015; 53:676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR et al Oxidative metabolism and PGC‐1β attenuate macrophage‐mediated inflammation. Cell Metab 2006; 4:13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hesketh M, Sahin KB, West ZE, Murray RZ. Macrophage phenotypes regulate scar formation and chronic wound healing. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Abdelaziz MH, Abdelwahab SF, Wan J, Cai W, Huixuan W, Jianjun C et al Alternatively activated macrophages; a double‐edged sword in allergic asthma. J Transl Med 2020; 18:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang F, Zhang S, Vuckovic I, Jeon R, Lerman A, Folmes CD et al Glycolytic stimulation is not a requirement for m2 macrophage differentiation. Cell Metab 2018; 28:463–75. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang LX, Zhang SX, Wu HJ, Rong XL, Guo J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol 2019; 106:345–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gong W, Huang F, Sun L, Yu A, Zhang X, Xu Y et al Toll‐like receptor‐2 regulates macrophage polarization induced by excretory‐secretory antigens from Schistosoma japonicum eggs and promotes liver pathology in murine schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0007000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fairfax KC, Amiel E, King IL, Freitas TC, Mohrs M, Pearce EJ. IL‐10R blockade during chronic Schistosoma mansoni results in the loss of B cells from the liver and the development of severe pulmonary disease. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ohlsson SM, Linge CP, Gullstrand B, Lood C, Johansson A, Ohlsson S et al Serum from patients with systemic vasculitis induces alternatively activated macrophage M2c polarization. Clin Immunol 2014; 152:10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shapouri‐Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F et al Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233:6425–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Duluc D, Delneste Y, Tan F, Moles MP, Grimaud L, Lenoir J et al Tumor‐associated leukemia inhibitory factor and IL‐6 skew monocyte differentiation into tumor‐associated macrophage‐like cells. Blood 2007; 110:4319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rattigan KM, Pountain AW, Regnault C, Achcar F, Vincent IM, Goodyear CS et al Metabolomic profiling of macrophages determines the discrete metabolomic signature and metabolomic interactome triggered by polarising immune stimuli. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0194126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Anders CB, Lawton TMW, Smith H, Garret J, Ammons MCB. Metabolic immunomodulation, transcriptional regulation, and signal protein expression define the metabotype and effector functions of five polarized macrophage phenotypes. bioRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.03.10.985788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wright JE, Werkman M, Dunn JC, Anderson RM. Current epidemiological evidence for predisposition to high or low intensity human helminth infection: a systematic review. Parasit Vectors 2018; 11:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Motran CC, Silvane L, Chiapello LS, Theumer MG, Ambrosio LF, Volpini X et al Helminth infections: recognition and modulation of the immune response by innate immune cells. Front Immunol 2018; 9:664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Castro GA. Helminths: structure, classification, growth, and development In: Baron S, ed. Medical Microbiology. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pullan RL, Smith JL, Jasrasaria R, Brooker SJ. Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasit Vectors 2014; 7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:1311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Measuring the burden of neglected tropical diseases: the global burden of disease framework. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2007; 1:e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hotez PJ, Bundy DAP, Beegle K, Brooker S, Drake L, de Silva N et al Helminth infections: soil‐transmitted helminth infections and schistosomiasis In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M. et al, Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press, 2006:467–82. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li EY, Gurarie D, Lo NC, Zhu X, King CH. Improving public health control of schistosomiasis with a modified WHO strategy: a model‐based comparison study. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7:e1414–e1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Deribew A, Kebede B, Tessema GA, Adama YA, Misganaw A, Gebre T et al Mortality and disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs) for common neglected tropical diseases in Ethiopia, 1990–2015: evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Ethiop Med J 2017; 55(Suppl 1):3–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hartgers FC, Obeng BB, Kruize YC, Duijvestein M, de Breij A, Amoah A et al Lower expression of TLR2 and SOCS‐3 is associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection and with lower risk for allergic reactivity in children living in a rural area in Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2:e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. McSorley HJ, Blair NF, Smith KA, McKenzie AN, Maizels RM. Blockade of IL‐33 release and suppression of type 2 innate lymphoid cell responses by helminth secreted products in airway allergy. Mucosal Immunol 2014; 7:1068–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Osbourn M, Soares DC, Vacca F, Cohen ES, Scott IC, Gregory WF et al HpARI protein secreted by a helminth parasite suppresses interleukin‐33. Immunity 2017; 47:739–51. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rzepecka J, Pineda MA, Al‐Riyami L, Rodgers DT, Huggan JK, Lumb FE et al Prophylactic and therapeutic treatment with a synthetic analogue of a parasitic worm product prevents experimental arthritis and inhibits IL‐1β production via NRF2‐mediated counter‐regulation of the inflammasome. J Autoimmun 2015; 60:59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Alvarado R, To J, Lund ME, Pinar A, Mansell A, Robinson MW et al The immune modulatory peptide FhHDM‐1 secreted by the helminth Fasciola hepatica prevents NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inhibiting endolysosomal acidification in macrophages. FASEB J 2017; 31:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rolot M, Dewals BG. Macrophage activation and functions during helminth infection: recent advances from the laboratory mouse. J Immunol Res 2018; 2018:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kreider T, Anthony RM, Urban JF Jr, Gause WC. Alternatively activated macrophages in helminth infections. Curr Opin Immunol 2007; 19:448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gundra UM, Girgis NM, Ruckerl D, Jenkins S, Ward LN, Kurtz ZD et al Alternatively activated macrophages derived from monocytes and tissue macrophages are phenotypically and functionally distinct. Blood 2014; 123:e110–e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Campbell SM, Knipper JA, Ruckerl D, Finlay CM, Logan N, Minutti CM et al Myeloid cell recruitment versus local proliferation differentiates susceptibility from resistance to filarial infection. eLife. 2018; 7 10.7554/elife.30947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Keselman A, Fang X, White PB, Heller NM. Estrogen signaling contributes to sex differences in macrophage polarization during asthma. J Immunol 2017; 199:1573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Osada Y, Kanazawa T. Parasitic helminths: new weapons against immunological disorders. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010; 2010:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Flohr C, Quinnell RJ, Britton J. Do helminth parasites protect against atopy and allergic disease? Clin Exp Aller 2009; 39:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Weinstock JV, Elliott DE. Helminths and the IBD hygiene hypothesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Aravindhan V, Mohan V, Surendar J, Muralidhara Rao M, Pavankumar N, Deepa M et al Decreased prevalence of lymphatic filariasis among diabetic subjects associated with a diminished pro‐inflammatory cytokine response (CURES 83). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4:e707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wiria AE, Hamid F, Wammes LJ, Prasetyani MA, Dekkers OM, May L et al Infection with soil‐transmitted helminths is associated with increased insulin sensitivity. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0127746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Chen Y, Lu J, Huang Y, Wang T, Xu Y, Xu M et al Association of previous schistosome infection with diabetes and metabolic syndrome: a cross‐sectional study in rural China. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2013; 98:E283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sanya RE, Webb EL, Zziwa C, Kizindo R, Sewankambo M, Tumusiime J et al The effect of helminth infections and their treatment on metabolic outcomes: results of a cluster‐randomised trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019. 10.1093/cid/ciz859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Lightowlers MW, Rickard MD. Excretory‐secretory products of helminth parasites: effects on host immune responses. Parasitology 1988; 96(Suppl):S123–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kahl J, Brattig N, Liebau E. The untapped pharmacopeic potential of helminths. Trends Parasitol 2018; 34:828–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Smallwood TB, Giacomin PR, Loukas A, Mulvenna JP, Clark RJ, Miles JJ. Helminth immunomodulation in autoimmune disease. Front Immunol 2017; 8:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Marcilla A, Trelis M, Cortes A, Sotillo J, Cantalapiedra F, Minguez MT et al Extracellular vesicles from parasitic helminths contain specific excretory/secretory proteins and are internalized in intestinal host cells. PLoS One 2012; 7:e45974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Jenkins SJ, Allen JE. Similarity and diversity in macrophage activation by nematodes, trematodes, and cestodes. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010; 2010:262609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Hajissa K, Muhajir A, Eshag HA, Alfadel A, Nahied E, Dahab R et al Prevalence of schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among school children in Um‐Asher Area, Khartoum, Sudan. BMC Res Notes 2018; 11:779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 2014; 383:2253–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Herbert DR, Holscher C, Mohrs M, Arendse B, Schwegmann A, Radwanska M et al Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 2004; 20:623–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Fairfax KC, Everts B, Smith AM, Pearce EJ. Regulation of the development of the hepatic B cell compartment during Schistosoma mansoni infection. J Immunol 2013; 191:4202–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Wolde M, Berhe N, Medhin G, Chala F, van Die I, Tsegaye A. Inverse associations of Schistosoma mansoni infection and metabolic syndromes in humans: a cross‐sectional study in Northeast Ethiopia. Microbiol Insights 2019; 12:1178636119849934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Versini M, Jeandel PY, Bashi T, Bizzaro G, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y. Unraveling the hygiene hypothesis of helminthes and autoimmunity: origins, pathophysiology, and clinical applications. BMC Med 2015; 13:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Luo X, Zhu Y, Liu R, Song J, Zhang F, Zhang W et al Praziquantel treatment after Schistosoma japonicum infection maintains hepatic insulin sensitivity and improves glucose metabolism in mice. Parasit Vectors 2017; 10:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hussaarts L, Garcia‐Tardon N, van Beek L, Heemskerk MM, Haeberlein S, van der Zon GC et al Chronic helminth infection and helminth‐derived egg antigens promote adipose tissue M2 macrophages and improve insulin sensitivity in obese mice. FASEB J 2015; 29:3027–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Barron L, Wynn TA. Macrophage activation governs schistosomiasis‐induced inflammation and fibrosis. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41:2509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Xu ZP, Chang H, Ni YY, Li C, Chen L, Hou M et al Schistosoma japonicum infection causes a reprogramming of glycolipid metabolism in the liver. Parasit Vectors 2019; 12:388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Nelson VL, Nguyen HCB, Garcia‐Canaveras JC, Briggs ER, Ho WY, DiSpirito JR et al PPARγ is a nexus controlling alternative activation of macrophages via glutamine metabolism. Genes Dev 2018; 32:1035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Odegaard JI, Ricardo‐Gonzalez RR, Goforth MH, Morel CR, Subramanian V, Mukundan L et al Macrophage‐specific PPARγ controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature 2007; 447:1116–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Huang JT, Welch JS, Ricote M, Binder CJ, Willson TM, Kelly C et al Interleukin‐4‐dependent production of PPAR‐γ ligands in macrophages by 12/15‐lipoxygenase. Nature 1999; 400:378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Assuncao LS, Magalhaes KG, Carneiro AB, Molinaro R, Almeida PE, Atella GC et al Schistosomal‐derived lysophosphatidylcholine triggers M2 polarization of macrophages through PPARγ dependent mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2017; 1862:246–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Pierelli G, Stanzione R, Forte M, Migliarino S, Perelli M, Volpe M et al Uncoupling protein 2: a key player and a potential therapeutic target in vascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017; 2:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Diano S, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Mol Med 2012; 18:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Mouser EE, Pollakis G, Smits HH, Thomas J, Yazdanbakhsh M, de Jong EC et al Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigen (SEA) and recombinant ω1 modulate induced CD4+ T‐lymphocyte responses and HIV‐1 infection in vitro . PLoS Pathog 2019; 15:e1007924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Qian XY, Ding WM, Chen QQ, Zhang X, Jiang WQ, Sun FF et al The metabolic reprogramming profiles in the liver fibrosis of mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum . Inflammation 2020; 43:731–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Ortega‐Molina A, Serrano M. PTEN in cancer, metabolism, and aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2013; 24:184–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Braun L, Grimes JET, Templeton MR. The effectiveness of water treatment processes against schistosome cercariae: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Sanin DE, Prendergast CT, Mountford AP. IL‐10 production in macrophages is regulated by a TLR‐Driven CREB‐mediated mechanism that is linked to genes involved in cell metabolism. J Immunol 2015; 195:1218–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Cosenza‐Contreras M, de Oliveira ECRA, Mattei B, Campos JM, Goncalves Silva G, de Paiva NCN et al The schistosomiasis SpleenOME: unveiling the proteomic landscape of splenomegaly using label‐free mass spectrometry. Front Immunol 2018; 9:3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Cortes‐Selva D, Elvington AF, Ready A, Rajwa B, Pearce EJ, Randolph GJ et al Schistosoma mansoni infection‐induced transcriptional changes in hepatic macrophage metabolism correlate with an athero‐protective phenotype. Front Immunol 2018; 9:2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Cortes‐Selva D, Gibbs L, Maschek JA, Van Ry T, Rajwa B, Cox JE et al Schistosoma mansoni infection reprograms the metabolic potential of the myeloid lineage in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. bioRxiv. 2020; 050898 10.1101/2020.04.20.050898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Liu PS, Wang H, Li X, Chao T, Teav T, Christen S et al α‐Ketoglutarate orchestrates macrophage activation through metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:985–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Humphries KH, Izadnegahdar M, Sedlak T, Saw J, Johnston N, Schenck‐Gustafsson K et al Sex differences in cardiovascular disease – impact on care and outcomes. Front Neuroendocrinol 2017; 46:46–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia 2014; 57:1542–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet 2014; 383:1973–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Wedekind C, Jakobsen PJ. Male‐biased susceptibility to helminth infection: an experimental test with a copepod. Oikos 1998; 81:458–62. [Google Scholar]

- 141. Everts B, Perona‐Wright G, Smits HH, Hokke CH, van der Ham AJ, Fitzsimmons CM et al ω1, a glycoprotein secreted by Schistosoma mansoni eggs, drives Th2 responses. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1673–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Steinfelder S, Andersen JF, Cannons JL, Feng CG, Joshi M, Dwyer D et al The major component in schistosome eggs responsible for conditioning dendritic cells for Th2 polarization is a T2 ribonuclease (ω1). J Exp Med 2009; 206:1681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Hams E, Bermingham R, Wurlod FA, Hogan AE, O'Shea D, Preston RJ et al The helminth T2 RNase ω1 promotes metabolic homeostasis in an IL‐33‐ and group 2 innate lymphoid cell‐dependent mechanism. FASEB J 2016; 30:824–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O'Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM et al Cell‐intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:846–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Huang SC, Smith AM, Everts B, Colonna M, Pearce EL, Schilling JD et al Metabolic reprogramming mediated by the mTORC2‐IRF4 signaling axis is essential for macrophage alternative activation. Immunity 2016; 45:817–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Malandrino MI, Fucho R, Weber M, Calderon‐Dominguez M, Mir JF, Valcarcel L et al Enhanced fatty acid oxidation in adipocytes and macrophages reduces lipid‐induced triglyceride accumulation and inflammation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015; 308:E756–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. de Gier B, Pita‐Rodriguez GM, Campos‐Ponce M, van de Bor M, Chamnan C, Junco‐Diaz R et al Soil‐transmitted helminth infections and intestinal and systemic inflammation in schoolchildren. Acta Trop 2018; 182:124–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Wiria AE, Hamid F, Wammes LJ, Prasetyani MA, Dekkers OM, May L et al Correction: infection with soil‐transmitted helminths is associated with increased insulin sensitivity. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0136002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Liu Z, Liu Q, Bleich D, Salgame P, Gause WC. Regulation of type 1 diabetes, tuberculosis, and asthma by parasites. J Mol Med 2010; 88:27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Wu D, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Ricardo‐Gonzalez RR, Jouihan HA, Bando JK et al Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science 2011; 332:243–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Sawant DV, Gravano DM, Vogel P, Giacomin P, Artis D, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cells limit induction of protective immunity and promote immune pathology following intestinal helminth infection. J Immunol 2014; 192:2904–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Wiria AE, Sartono E, Supali T, Yazdanbakhsh M. Helminth infections, type‐2 immune response, and metabolic syndrome. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Pace F, Carvalho BM, Zanotto TM, Santos A, Guadagnini D, Silva KLC et al Helminth infection in mice improves insulin sensitivity via modulation of gut microbiota and fatty acid metabolism. Pharmacol Res 2018; 132:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Viney M, Kikuchi T. Strongyloides ratti and S. venezuelensis – rodent models of Strongyloides infection. Parasitology 2017; 144:285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Lancaster GI, Langley KG, Berglund NA, Kammoun HL, Reibe S, Estevez E et al Evidence that TLR4 is not a receptor for saturated fatty acids but mediates lipid‐induced inflammation by reprogramming macrophage metabolism. Cell Metab 2018; 27:1096–110. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Rajamanickam A, Munisankar S, Bhootra Y, Dolla C, Thiruvengadam K, Nutman TB et al Metabolic consequences of concomitant Strongyloides stercoralis infection in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Weng M, Huntley D, Huang IF, Foye‐Jackson O, Wang L, Sarkissian A et al Alternatively activated macrophages in intestinal helminth infection: effects on concurrent bacterial colitis. J Immunol 2007; 179:4721–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Maizels RM, Hewitson JP. Myeloid cell phenotypes in susceptibility and resistance to helminth parasite infections. Microbiol Spectr 2016;4 10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0043-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Yang Z, Grinchuk V, Urban JF Jr, Bohl J, Sun R, Notari L et al Macrophages as IL‐25/IL‐33‐responsive cells play an important role in the induction of type 2 immunity. PLoS One 2013; 8:e59441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Leroux LP, Nasr M, Valanparambil R, Tam M, Rosa BA, Siciliani E et al Analysis of the Trichuris suis excretory/secretory proteins as a function of life cycle stage and their immunomodulatory properties. Sci Rep 2018; 8:15921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Su CW, Chen CY, Li Y, Long SR, Massey W, Kumar DV et al Helminth infection protects against high fat diet‐induced obesity via induction of alternatively activated macrophages. Sci Rep 2018; 8:4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A et al Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med 2013; 210:535–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Yang Z, Grinchuk V, Smith A, Qin B, Bohl JA, Sun R et al Parasitic nematode‐induced modulation of body weight and associated metabolic dysfunction in mouse models of obesity. Infect Immun 2013; 81:1905–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. van den Berg SM, van Dam AD, Kusters PJH, Beckers L, den Toom M, van der Velden S et al Helminth antigens counteract a rapid high‐fat diet‐induced decrease in adipose tissue eosinophils. J Mol Endocrinol 2017; 59:245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]