Abstract

Gait biomechanics after anterior cruciate ligament injury are associated with functional outcomes and the development of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. However, biomechanical outcomes between patients treated non-operatively compared to operatively are not well understood. The primary purpose of this study was to compare knee joint contact forces, angles, and moments during loading response of gait between individuals treated with operative compared to non-operative management at 5 years after ACL injury. Forty athletes treated operatively and 17 athletes treated non-operatively completed gait analysis at 5 years after ACL reconstruction or completion of non-operative rehabilitation. Medial compartment joint contact forces were estimated using a previously validated, patient-specific electromyography-driven musculoskeletal model. Knee joint contact forces, angles, and moments were compared between the operative and non-operative group using mixed model 2×2 ANOVA’s. Peak medial compartment contact forces were larger in the involved limb of the non-operative group (Op: 2.37±0.47 BW, Non-Op: 3.03±0.53 BW; Effect Size: 1.36). Peak external knee adduction moment was also larger in the involved limb of the non-operative group (Op: 0.25±0.08 Nm/kg·m, Non-Op: 0.32±0.09 Nm/kg·m; Effect Size: 0.89). No differences in radiographic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis were present between the operative and non-operative group. Overall, participants treated non-operatively walked with greater measures of medial compartment joint loading than those treated operatively, while sagittal plane group differences were not present.

Statement of Clinical Relevance:

The differences in medial knee joint loading at 5 years after operative and non-operative management of anterior cruciate ligament injury may have implications on the development of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis.

Keywords: ACL, kinematics and kinetics, rehabilitation, knee, joint contact force

INTRODUCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a frequent injury for individuals participating in cutting and pivoting activities. An estimated 120,000 ACL injuries occur each year in the United States, with the greatest incidence among high school and college-aged individuals.1 ACL injury results in a loss of knee joint stability and development of abnormal movement patterns.2–6 This has significant consequences as 50% of those with ACL injury develop knee osteoarthritis within 10–20 years of injury.7 Altered movement patterns and knee joint loading may contribute to subsequent knee osteoarthritis development.8–10 Restoring passive knee joint stability through operative treatment (early ACL reconstruction) was previously thought to alleviate gait deviations and protect against the development of osteoarthritis.11–13 Although operative treatment addresses excessive anterior tibial translation, the risk of knee osteoarthritis is similar when compared to knees managed non-operatively.14 Further, both operative and non-operative treatment of ACL injury result in similar levels of knee function and participation in cutting and pivoting activities, following a period of rehabilitation.15,16 This evidence supports non-operative management of ACL injury as a viable alternative to operative treatment to achieve successful functional outcomes. However, biomechanical outcomes between patients treated non-operatively compared to operatively are not well understood.

Gait patterns change within weeks of ACL injury.17,18 Compared to the uninjured limb, patients walk with lower peak knee joint angles and moments, most notably in the sagittal plane. Lower involved knee joint angles and moments in the sagittal plane continue throughout the first year after surgery.4,5 Joint loading in the involved knee appears to increase and match the uninvolved knee 1 year after operative treatment; a meta-analysis by Hart et al. reported no differences in interlimb peak knee flexion angles and moments during periods of 1–3 years and ≥3 years after ACL reconstruction.4 Hart and colleagues did not observe any differences in frontal plane angles or moments in their pooled analyses compared to either the contralateral limb or to healthy control groups.4 While gait biomechanics have been extensively studied after operative treatment, fewer studies have investigated gait biomechanics following non-operative ACL management. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ismail et al. reported no differences in sagittal plane knee angles and moments in patients treated non-operatively 6 months of ACL injury compared to control cohorts.6 Ismail and colleagues were unable to pool data regarding frontal plane angles and moments in non-operative ACL cohorts secondary to limited quantitative reporting of these variables.

Previous work investigating biomechanical movement patterns after ACL injury has focused on comparisons of either ACL-deficient or ACL-reconstructed cohorts to control cohorts without ACL injury. These study designs do not directly compare the effect of ACL reconstruction compared to non-operative management on aberrant movement patterns. The goal of this study was to advance our understanding of the effect of surgical intervention on gait biomechanics after ACL injury, by directly comparing patients completing operative and non-operative ACL management. To address this goal, the primary aim of this study was to compare knee joint contact forces, angles, and moments during gait between individuals treated with operative compared to non-operative management at 5 years after ACL injury. We hypothesized that no differences in knee joint contact forces, angles, and moments would be present during gait between the operative and non-operative groups. This hypothesis was developed from evidence that medium- to long-term functional outcomes do not differ after non-operative management compared to ACL reconstruction,14,16 and that persistent movement asymmetries after ACL injury during activities such as gait predict functional performance. For example, Hartigan et al. reported that a lower external knee flexion moment during gait was a significant predictor of failing a functional return-to-sport test battery (quadriceps strength, single-legged hop tests, subjective knee function) at 6 months after ACL reconstruction.19 Pietrosimone et al. reported that individuals who walk with lower vertical ground reaction forces compared to their uninjured limb at 6 months after ACL reconstruction present with lower scores on the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) at 12 months after surgery.20 A secondary purpose was to compare knee extensor and flexor muscle forces during gait between individuals treated with operative compared to non-operative management at 5 years after ACL injury. A supplemental analysis comparing hip joint angles and moments during gait in this cohort is present in Supplemental Table 1.

METHODS

Participants

Individuals between the ages of 13–55 years with a complete, acute ACL injury who were active in a minimum of 50 hours per year of level 1–2 cutting and pivoting activities21,22 prior to injury were eligible for this study. All participants in this study were part of a previously completed randomized control trial (55 patients)23 or ongoing prospective cohort study (150 patients)24 investigating the effects of neuromuscular training coupled with progressive quadriceps strengthening completed after ACL injury. Studies were approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board, and all patients (or patient guardians if under 18 years old) completed written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included concomitant grade III injury to other knee ligaments, a repairable meniscus or full-thickness chondral lesions greater than 1 cm2 diagnosed on magnetic resonance imaging at time of ACL injury, prior history of ACL injury in either knee, or additional second ACL injury in either knee.

All patients completed progressive, criterion-based pre-operative or non-operative rehabilitation at a single, outpatient physical therapy clinic using previously reported protocols.25,26 Following initial resolution of knee impairments after ACL injury (range of motion, pain, effusion, isometric quadriceps strength), patients were categorized as a potential coper if no more than 1 giving way episode occurred since ACL injury, a score of ≥80% of the Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale,27 a score of ≥60% on the Global Rating Scale of Perceived Function, and a score of ≥80% on the 6-meter timed hop.28 If any of these criteria were not met, the patient was categorized as a noncoper. In addition, patients completed an additional 10 physical therapy treatment sessions focusing on neuromuscular training and further strength training, irrespective of plans for operative or non-operative management of injury. Surgical decisions were made by the patient using orthopaedic surgeon and physical therapist input. For patients choosing operative management, anatomic ACL reconstruction was completed by a single, board-certified orthopedic surgeon using either a four-bundle semitendinosus-gracilis autograft or soft tissue allograft. All operative patients completed post-operative, criterion-based rehabilitation at the same outpatient physical therapy clinic previously described.29 For patients choosing non-operative management, patients continued rehabilitation as needed until meeting University of Delaware return to sport criteria (90% quadriceps strength and four single-legged hop test scores compared to contralateral limb, 90% Knee Outcome Survey – Activities of Daily Living Scale, 90% Global Rating Scale).29

Biomechanical Gait Analysis and EMG-Driven Musculoskeletal Modeling

Participants completed biomechanical gait analysis in shoes 5 years after ACL reconstruction or completion of non-operative rehabilitation. A passive, retro-reflective marker set consisting of single markers at bony landmarks of the pelvis and both lower extremities and thermoplastic, rigid marker shells at the posterior pelvis and each thigh and shank were placed on each participant.30 This marker set has previously demonstrated reliability during gait.31 Stance phase kinematics, kinetics, and surface EMG data was collected using an 8-camera motion capture system sampled at 120 Hz (VICON, Oxford Metrics Ltd., London, UK), one embedded Bertec force platform sampled at 1,080 Hz (Bertec Corporation, Worthington, OH), and an MA-300 EMG system sampled at 1,080 Hz (Motion Lab Systems, Baton Rouge, LA). Participants were instructed to walk at a comfortable walking speed. After establishing self-selected walking speed, participants completed eight gait trials for each limb along a 20-meter walkway while maintaining walking speed (±5% of established baseline speed using timing gates), with the mean of three trials in each limb reported in this study. Kinematic and kinetic data were low-passed filtered at 6 Hz and 40 Hz, respectively. Knee and hip joint angles and moments were calculated using inverse dynamics within custom Visual 3D programming (C-Motion, Germantown, MD). External joint moments were normalized to mass (kg) and height (m). Stance phase gait speed was calculated as the horizontal velocity of the center of mass of the modeled pelvis from heel strike to toe off in the involved limb.

Electromyography (EMG) data was also collected during maximal voluntary isometric contractions of each muscle group against external resistance using testing positions previously described32 before gait trials and during each gait trial. Surface electrodes were placed at the mid-belly of seven lower extremity muscles (vastus medialis and lateralis, rectus femoris, semitendinosis, long head of biceps femoris, and medial and lateral gastrocnemii) following skin preparation using rubbing alcohol and hair removal. Surface EMG data were high-pass filtered at 30 Hz (2nd order Butterworth), rectified, and low-pass filtered at 6 Hz (2nd order Butterworth) to create linear envelopes within Visual 3D. The linear envelope of each muscle was normalized to maximal values during maximal voluntary isometric contraction or any of the gait trials. The linear envelope for the semimembranosus was set equal to the semitendinosus, and the linear envelope for the short head of the biceps femoris was set equal to the long head of the biceps femoris due to the inability of surface EMG to accurately measure deep muscles.

EMG, kinematic, and kinetic data served as inputs to a patient-specific, EMG-driven musculoskeletal model used to estimate tibiofemoral joint contact forces.33 This musculoskeletal model has been previously validated by accurately predicting in vivo joint contact forces during gait in an individual with an instrumented knee prosthesis.34 Full details of this modeling approach and validation have previously been described elsewhere.32,33 Briefly, a Hill-type neuromusculoskeletal model that depends on both time-dependent variables (muscle activation, muscle fiber length, velocity and pennation angle) as well as time invariant variables (optimal fiber length, tendon slack length and maximum isometric muscle force) was used to compute the force generated by each muscle.35 The musculoskeletal model included the foot, shank, thigh and pelvis segments as well as 10 muscles crossing the knee (rectus femoris, medial and lateral vasti, vastus intermedius, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, short and long head of biceps femoris, medial and lateral gastrocnemii). Based on individual muscle forces, the model further computed the internal sagittal plane knee joint moment using a forward-dynamics approach, which was then calibrated against the external sagittal plane knee joint moment obtained from an inverse-dynamics approach. After patient-specific calibration, individual muscle forces as well medial compartment contact force for three novel gait trials were estimated.

Biomechanical Variables of Interest

The primary outcome of interest was the peak medial compartment contact force during the first half of stance. Secondary variables of interest included peak knee flexion angle, peak knee adduction angle (during first 50% of stance), peak knee flexion moment, peak knee adduction moment (during first 50% of stance), knee extensor muscle force, and knee flexor muscle force. These biomechanical variables were chosen because they are commonly altered after ACL injury4–6 and are associated with knee osteoarthritis development after ACL injury.8,36 Knee extensor muscle force was defined as the sum of the rectus femoris, medial and lateral vasti, and vastus intermedius muscle forces at the time of peak medial compartment contact force. Knee flexor muscle force was defined as the sum of the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, short and long head of biceps femoris, and medial and lateral gastrocnemii muscle forces at the time of peak medial compartment contact force. Medial compartment contact force, knee extensor muscle force, and knee flexor muscle force were normalized to body weight (BW).

Peak hip joint angle and external moment variables of interest (presented in Supplemental Table 1) included the hip flexion angle, hip extension angle, hip adduction angle (during first 50% of stance), hip flexion moment, hip extension moment, and hip adduction moment (during first 50% of stance). Hip excursion in the sagittal plane was calculated as the difference between the peak hip flexion angle and peak hip extension angle.

Clinical Measures of Knee Function

The participants in this study were included in a previous larger analysis of functional and radiographic outcomes after operative compared to non-operative management at 5 years after ACL injury.16 Quadriceps strength, subjective knee function on the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), and activity level21,22 are reported for participants in this study. Quadriceps strength was measured isometrically in the seated position with 90⁰ of hip and knee flexion using the burst superimposition technique on an electromechanical dynamometer (Kin-Com; DJO Global).37 A quadriceps index was calculated by taking the maximal voluntary isometric contraction of the involved limb divided by that of the uninvolved limb multiplied by 100%. The KOOS is a reliable and valid subjective measure of knee function widely used after ACL injury.38,39 It has 5 sub-scales: pain, symptoms, function in daily living, function in sports and recreational activities, and knee-related quality of life.

Radiographs

Participants completed bilateral weightbearing, posterior-anterior bent knee (30⁰) radiographs at 5 years after ACL reconstruction or completion of non-operative ACL management. Radiographs were view in SigmaView software (Agfa HealthCare Corporation) and scored using the Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grading system40 in both the medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartment by a single grader (E.W.) with previously established grading reliability.16 All KL grades were verified by a board-certified orthopaedic surgeon. Radiographic osteoarthritis was defined by a KL grade of 2 or greater in either the medial or lateral tibiofemoral compartment or both.

Power and Statistical Analysis

Power analysis was completed using G*Power 3.141 with the primary outcome of peak medial compartment contact force. Using the ratio of operative to non-operative participants in this study cohort of 4:1, the minimal detectable change (MDC) for peak medial compartment contact force of 0.30 BW with a standard deviation of 0.30 BW,42 and α=0.05, 42 operative participants and 10 non-operative participants were needed to achieve 80% statistical power using a two-sided test.

Statistical analyses were completed using PASSW 25.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Fisher’s exact tests, Chi-square tests, and independent t-tests were used to compare baseline characteristics, frequency of second ACL injuries, clinical measures of knee function, and KL grades at 5 years between the operative and non-operative treatment groups. A mixed model 2×2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test peak biomechanical gait variables with group (operative vs. non-operative) as the between-subjects factor and limb as the within-subjects factor. If a significant interaction factor was present, interlimb differences in the biomechanical variable of interest (involved minus uninvolved) were compared between the operative and non-operative groups using independent t-tests. MDC and effect sizes (ES) were used qualitatively to determine if meaningful differences existed between the operative and non-operative group and between limbs.42–44 A prior statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics, Clinical Measures of Knee Function, and Radiographic Outcomes

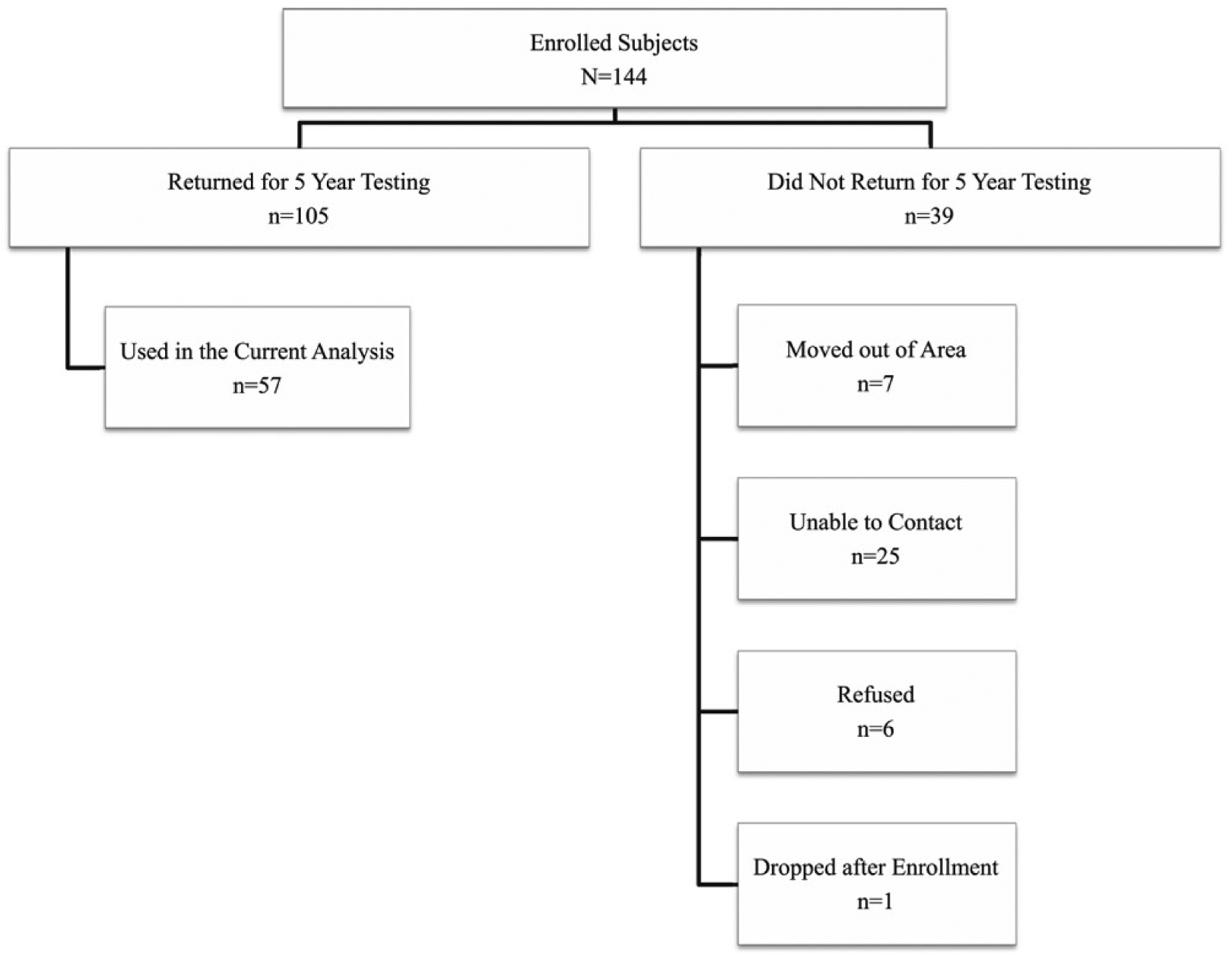

The first 40 patients after ACL reconstruction and 17 patients who completed non-operative management who returned for 5-year testing were included in the current analysis (Figure 1). In the operative group, 12 patients were treated with a semitendinosus-gracilis autograft and 28 with a soft tissue allograft. The operative and non-operative group did not differ in age, sex, body mass index, pre-injury cutting and pivoting activity level, concomitant medial meniscus injury, frequency of second ACL injuries, timing of 5-year testing, or gait speed (Table 1). A greater proportion of operatively treated participants demonstrated dynamic knee instability (i.e. classified as noncopers28) early after ACL injury compared to non-operatively treated participants (Table 1). At 5 years after ACL reconstruction or completion of non-operative management, the operative and non-operative group did not differ in quadriceps strength, KOOS scores, or activity levels (Table 2). All patients treated non-operatively and 36 of 40 patients treated operatively completed radiographs at 5 years. One (5.9%) patient treated non-operatively and six (16.7%) patients treated operatively had radiographic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis at 5 years (p=0.408) (Table 2). No patients with tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in the injured knee had radiographic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in the uninjured knee.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study cohort

Table 1:

Baseline and second ACL injury characteristics between patients who completed operative compared to non-operative management of ACL injury.

| Op (n=40) | Non-Op (n=17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (at 5-year testing) (yrs) | 37.1 (11.6) | 37.5 (13.7) | 0.928 |

| Sex (M:F) | 27:13 | 8:9 | 0.234 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (4.6) | 26.3 (4.7) | 0.555 |

| Pre-Injury Activity Level (1:2)21,22 | 24:16 | 7:10 | 0.249 |

| Noncoper:Potential Coper28 | 27:13 | 6:11 | 0.039 |

| Medial Meniscus Injury (on post-ACL injury MRI) (Yes:No) | 11:29 | 6:11 | 0.547 |

| Partial Medial Meniscectomy During ACL Reconstruction (Yes:No) | 6:34 | - | - |

| Medial Meniscus Repair During ACL Reconstruction (Yes:No) | 2:38 | - | - |

| Second ACL injury before 5-year testing (contralateral or graft rupture) (Yes:No) | 4:36 | 0:17 | 0.306 |

| Contralateral second ACL injury before 5-year testing (Yes:No) | 1:39 | 0:17 | >0.999 |

| Time from ACL reconstruction/non-op rehabilitation to 5-year testing (yrs) | 5.3 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | 0.255 |

| Gait Speed (m/s) | 1.58 (0.12) | 1.61 (0.14) | 0.380 |

Boldface numbers indicate statistically significant group differences. Values within parentheses represent standard deviations. Abbreviations: Op, operative; Non-Op, non-operative; yrs, years; kg, kilogram; m, meter; M, male; F, female; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2:

Clinical measures of knee function and radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the involved knee at 5 years between patients who completed operative compared to non-operative management of ACL injury. Radiographic data is missing for 4 patients in the operative group.

| Op (n=40) | Non-Op (n=17) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | p | |

| Quadriceps Index (%) | 103.5 (19.4) | 97.2 to 109.8 | 103.5 (18.3) | 93.4 to 113.6 | 0.997 |

| KOOS-Pain Subscale (%) | 97.2 (4.9) | 95.6 to 98.8 | 93.8 (10.2) | 88.5 to 99.0 | 0.094 |

| KOOS-Symptoms Subscale (%) | 91.3 (9.2) | 88.3 to 94.3 | 91.6 (11.5) | 85.7 to 97.5 | 0.922 |

| KOOS-ADL Subscale (%) | 99.0 (2.2) | 98.3 to 99.7 | 97.2 (6.1) | 94.1 to 100.4 | 0.109 |

| KOOS-Sport/Rec Subscale (%) | 93.1 (11.8) | 89.2 to 96.9 | 88.8 (19.8) | 78.6 to 99.0 | 0.323 |

| KOOS-QoL Subscale (%) | 89.6 (15.2) | 84.7 to 94.5 | 80.5 (18.3) | 71.1 to 90.0 | 0.060 |

| Activity Level at 5 Years (1:2:3:4)21,22 | 21:8:10:1 | - | 6:4:6:1 | - | 0.647 |

| Participating at Pre-Injury Activity Level at 5 Years (Yes:No)21,22 | 26:14 | - | 9:8 | - | 0.553 |

| Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis (KL Grade ≥ 2) (Yes:No) | 6:30 | - | 1:16 | - | 0.408 |

Abbreviations: Op, operative; Non-Op, non-operative; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; ADL, activities of daily living; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; KL, Kellgren-Lawrence.

Primary Outcome: Peak Medial Compartment Contact Force

Peak medial compartment contact forces were larger in the non-operative group than the operative group (p<0.001) (Table 3). The between-group difference of 0.66 BW in peak medial compartment contact force in the involved limb (Op: 2.37±0.47 BW, Non-Op: 3.03±0.53 BW; ES: 1.36) exceeded the MDC of 0.30 BW for this variable.42 A post-hoc power analysis using peak medial compartment contact force data for the 40 operatively-treated and 17 non-operatively treated patients with α=0.05 resulted in a statistical power value of 99.4%. The non-operative group loaded the involved knee 0.27 BW more than the uninvolved knee, but this difference was not statistically different compared to the operative group (Table 3). The operative group demonstrated symmetric peak contact forces during gait (interlimb difference: −0.01 BW) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Involved and uninvolved limb medial compartment contact force, sagittal and frontal plane knee angles and moments, and knee muscle forces during stance phase of gait between patients completing operative compared to non-operative management of ACL injury.

| Operative | Non-Operative | Mixed Model ANOVA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved | Uninvolved | Involved | Uninvolved | p-values | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Group | Limb | Interaction | |

| pMCCF (BW) | 2.37 (0.47) | 2.23 to 2.52 | 2.38 (0.48) | 2.23 to 2.54 | 3.03 (0.53) | 2.76 to 3.30 | 2.77 (0.64) | 2.44 to 3.10 | <0.001* | 0.168 | 0.143 |

| pKFA (°) | 23.5 (5.4) | 21.8 to 25.2 | 23.4 (5.0) | 21.8 to 25.0 | 22.9 (7.3) | 19.1 to 26.6 | 23.3 (6.7) | 19.7 to 26.6 | 0.798 | 0.899 | 0.739 |

| pKAA (°) | 2.7 (2.4) | 1.9 to 3.4 | 3.5 (2.1) | 2.9 to 4.2 | 2.8 (2.9) | 1.3 to 4.3 | 4.7 (3.2) | 3.0 to 6.3 | 0.308 | 0.001* | 0.204 |

| pKFM (Nm/kg∙m) | 0.50 (0.12) | 0.46 to 0.54 | 0.51 (0.11) | 0.48 to 0.55) | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.48 to 0.57 | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.49 to 0.58 | 0.430 | 0.503 | 0.987 |

| pKAM (Nm/kg∙m) | 0.25 (0.08) | 0.23 to 0.27 | 0.27 (0.09) | 0.24 to 0.30 | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.28 to 0.37 | 0.28 (0.09) | 0.24 to 0.33 | 0.046* | 0.422 | 0.026* |

| EXT at pMCCF (BW) | 2.74 (0.71) | 2.51 to 2.97 | 2.65 (0.70) | 2.43 to 2.87 | 2.77 (0.71) | 2.40 to 3.14 | 2.68 (0.47) | 2.44 to 2.92 | 0.855 | 0.387 | 0.983 |

| FLEX at pMCCF (BW) | 0.94 (0.41) | 0.81 to 1.07 | 1.04 (0.42) | 0.91 to 1.18 | 1.02 (0.46) | 0.79 to 1.26 | 0.94 (0.43) | 0.72 to 1.16 | 0.929 | 0.889 | 0.188 |

Boldface numbers indicate statistically significant group differences. Abbreviations: pMCCF, peak medial compartment contact force; pKFA, peak knee flexion angel; pKAA, peak knee adduction angle; pKFM, peak knee flexion moment; pKAM, peak knee adduction moment, EXT, knee extensor muscle forces; FLEX, knee flexor muscle forces; BW, body weight; °, degrees; N, Newton; m, meter; kg, kilogram; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Secondary Outcomes: Knee Joint Angles, Moments, and Muscle Forces

There was a significant interaction effect for peak knee adduction moment (p=0.026, Table 3). Post-hoc comparisons of the interlimb differences showed that patients treated non-operatively walked with larger knee adduction moments in the involved limb compared to the uninvolved limb, whereas the patients treated operatively did not (interlimb difference in peak knee adduction moment: p: 0.026; Op: −0.02±0.08 Nm/kg·m, Non-Op: 0.04±0.10 Nm/kg·m; ES: 0.66). There was also a main effect of limb (p=0.046) for peak knee adduction moment, characterized by larger values in the non-operative group than the operative group (Table 3). The between-group difference of 0.07 Nm/kg·m in peak knee adduction moment in the involved limb (Op: 0.25±0.08 Nm/kg·m, Non-Op: 0.32±0.09 Nm/kg·m; ES: 0.89) exceeded the MDC of 0.06 Nm/kg·m for this variable.42 Peak knee adduction angle was statistically smaller in the involved limb compared to the uninvolved limb (p=0.001; Involved: 2.7±2.5°; Uninvolved: 3.9±2.5°; ES: 0.46) but did not exceed the MDC of 1.7° for this variable42 and was likely not clinically meaningful. No differences in peak knee flexion angles, peak knee flexion moment, or knee extensor and flexor muscle forces at the time of peak medial compartment contact force were present by group or limb (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that patients treated with non-operative management of ACL injury walked with 28% greater peak medial compartment contact force (equal to two-thirds bodyweight) and also 28% greater peak knee adduction moment in the involved knee compared to patients treated operatively at 5 years. The similar findings for both medial compartment contact forces and knee adduction moments is not surprising, as the knee adduction moment is used within our musculoskeletal modeling approach and previously shown to predict medial compartment contact forces.45,46 The group difference in the involved peak knee adduction moment resulted in an interlimb peak knee adduction moment difference in which the non-operative group walked with a greater peak knee adduction moment in the involved compared to uninvolved limb (interlimb difference = 0.04 Nm/kg∙m) compared a lower knee adduction moment in the involved limb of the operative group (−0.02 Nm/kg∙m). Peak knee flexion and adduction angles and knee flexion moment did not differ between the operative and non-operative group at 5 years, nor did knee extensor and flexor muscle forces.

Medial compartment contact forces using the same EMG-drive musculoskeletal model were previously reported in nine physically active, uninjured individuals.42 The medial compartment contact force of the operative group (2.37±0.47 BW) was more similar to the uninjured cohort (2.48±0.30 BW) than the non-operative group (3.03±0.53 BW). However, it is unknown whether higher or lower medial joint loading is protective to long-term knee joint health after ACL injury, particularly after non-operative management. After ACL reconstruction, we have previously shown that patients with radiographic knee osteoarthritis at 5 years walked with lower medial compartment contact forces and peak knee adduction moments before and 6 months after ACL reconstruction than those who did not develop knee osteoarthritis.8 Others have demonstrated similar links to low joint loading early after ACL injury and signs of articular cartilage breakdown, but caution must be used as none of these studies include patients treated non-operatively.10,47 In the current study, only 5.9% of patients treated non-operatively had radiographic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis at 5 years, compared to 16.7% of patients treated operatively. These findings indicate that the higher medial compartment contact forces and external knee adduction moments during gait in the non-operative group may not be harmful to knee joint health at 5 years. Magnetic resonance imaging was not completed in this cohort at 5 years. Thus, pre-radiographic signs of osteoarthritis cannot be ruled out.

The absence of surgery in the non-operative group may contribute to the low rates of knee osteoarthritis in the non-operative group, or a slower rate of disease progression. Patients treated non-operatively may demonstrate shorter periods of the typical underloading period after ACL injury because they do not undergo a second major trauma and inflammatory event in ACL surgery compared to patients treated operatively. At 5 years after ACL reconstruction, patients with radiographic knee osteoarthritis walk with lower knee flexion angles and moments but not with different knee adduction moments and medial compartment contact forces.36 Further, returning to pivoting sport after ACL reconstruction has been shown to decrease the odds of developing symptomatic and radiographic knee osteoarthritis at 15 years.48 Together, these previous studies suggest that higher levels of joint loading may not be harmful after ACL injury. However, excessive joint laxity that persists after non-operative management of ACL injury may result in portions of the joint experiencing load for which it was not previously conditioned and result in joint degeneration.49 For example, Yang and colleagues reported that anterior-posterior translation measured using computed tomography (CT) bone modelling and biplane radiography during weight acceptance of the gait was greater in ACL-deficient knees in comparison to the contralateral limb in patients despite no symptoms of knee instability.50 Studies with longer-term follow-up are needed to clarify the role of joint loading in the osteoarthritis pathway after operative and non-operative management of ACL injury to further place the current findings of 5-year gait biomechanics within the context of long-term joint health.

Two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated interlimb differences in long-term walking patterns in patients after operative and non-operative treatment of ACL injury.4,6 The results of the present study are in accordance with these reviews that reported no interlimb differences in sagittal plane knee joint angles or moments during loading response of gait in both operative and non-operative groups of patients at least 3 years after ACL reconstruction or ACL injury (if treated non-operatively). Greater levels of passive knee joint laxity persist without ACL reconstruction. However, the findings of this study suggest that ACL reconstruction is not required to restore symmetric knee flexion angles and moments during gait.

The progression of frontal plane joint moments after ACL injury is less clear that its sagittal plane counterparts. For example, no studies included in the systematic review by Ismail et al. compared interlimb differences in the frontal plane in non-operatively treated patients.6 In the current study, patients completing non-operative ACL management walked with a greater knee adduction moment than the contralateral limb and the injured limb of those completing operative management. A previous study within a separate ACL cohort reported that patients who have a medial meniscectomy concomitantly with ACL reconstruction walk with a greater peak knee adduction moment than patients undergoing medial meniscal repair or no medial meniscus procedure.51 These previous findings, along with the smaller number of patients who underwent medial meniscectomy with ACL reconstruction (n=6), do not explain the lower peak knee adduction moment present in the operative group. Another study completed by Ismail et al. completed after publication of the systematic review6 investigated 43 non-operatively treated patients at 34.5±55.6 months after injury.52 Unlike the current findings, they found no interlimb differences in the knee adduction moment (as well as the knee flexion moment) during stance phase of gait. The different findings may be explained by the difference in time since ACL injury of the two studies. In the current study, testing was completed within a tight window of 5 years (standard deviation of 0.5 years). However, in the study completed by Ismail et al., patients were eligible as soon as 6 months after ACL injury, and the standard deviation for testing of 55.6 months indicates patients were tested within a wide range of time since injury. It is possible that frontal plane knee joint underloading and overloading characteristics of gait change with time after ACL injury. If so, interlimb differences could be washed out within a cohort that is heterogeneous regarding time since injury.

A strength of this study is the direct comparisons of an operative and non-operative group of patients after ACL injury who had similar pre-injury characteristics (i.e. age, sex, activity levels) which few previous studies have done. Markström and colleagues investigated differences in hip and knee joint angles during a vertical hop in patients treated operatively and non-operatively 23 years after injury.53 Both groups demonstrated interlimb differences at the hip and knee across the sagittal, frontal and transverse planes that were not present in uninjured individuals. However, both the operative and non-operative group presented with lower Tegner activity levels (median = 4) than the uninjured control group (median = 6), indicating the ACL group was completing less routine vertical hopping activities than the uninjured control group at the time of testing. The low Tegner activity level may have impacted the ability of the ACL group to successfully complete the vertical hop task.

The operative and non-operative groups presented with similar levels of function and activity 5 years after ACL reconstruction or completion of non-operative rehabilitation, respectively. Both groups demonstrated high quadriceps strength and KOOS scores. Baseline characteristics of the non-operative and operative groups were also similar. However, a higher proportion of patients that were categorized by noncopers early after ACL injury elected to have ACL reconstruction instead of pursuing non-operative management. Noncopers can be identified through a clinical battery of tests (i.e. hop tests, subjective knee function, history of knee giving ways) and are defined by a knee “stiffening” strategy during gait that is more apparent than their potential coper counterparts.54 The higher proportion of noncopers in the operatively treated group in the current study could account for biomechanical differences present at 5 years. Therefore, a separate secondary analysis of the noncopers and potential copers in the operative group was completed. At 5 years after ACL reconstruction, independent t-tests showed no differences between noncopers and potential copers in any of the knee variables included in this study, including peak medial compartment contact force (p: 0.205; Noncoper: 2.31±0.42 BW, Potential Coper: 2.51±0.54 BW), peak knee adduction moment (p: 0.587; Noncoper: −0.01±0.07 Nm/kg·m, Potential Coper: −0.04±0.08 Nm/kg·m), and interlimb difference of peak knee adduction moment (p: 0.203; Noncoper: 0.25±0.08 Nm/kg·m, Potential Coper: 0.32±0.09 Nm/kg·m). These additional findings support that biomechanical gait differences and similarities between operatively and non-operatively treated patients present at 5 years in this study were not driven by the proportional group differences of noncopers versus potential copers.

There are several additional strengths of the current study. Analyses of the included patients occurred within a tight timeframe of 5 years after ACL reconstruction or non-operative rehabilitation. Many previous studies include patients over a wide time range, such as the systematic review of biomechanics in non-operatively treated patients 6–240 months after ACL injury.6 Gait biomechanics after ACL injury change with time. Thus, it may not always be appropriate to summarize movements patterns in these groups of patients. Next, extensive clinical and patient-reported data at both pre-operative and 5-year time points is known for both the operative and non-operative group. An understanding of knee function levels provides key clinical context in which to interpret these biomechanical findings. This study also incorporated mechanistic evaluation of joint angles and moments with an EMG-driven musculoskeletal model to provide advance metrics of knee joint biomechanics including joint contact and muscle forces during gait. Study limitations were also present. Longitudinal biomechanical data of the study cohort does not exist. Thus, comparisons of biomechanical gait profiles between the non-operative and operative group at earlier time points could not be completed. Further, group comparisons of multiple biomechanical variables were completed that increased the risk for false positive findings. However, group differences had medium to large effect sizes and exceeded MDC thresholds suggesting these findings represent true group differences.

In summary, the findings of this study suggest that patients treated non-operatively after ACL injury walk with greater medial compartment contact forces and peak knee adduction moments at 5 years than patients treated operatively. These differences in medial knee joint loading may have implications on the development of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis after operative and non-operative management of ACL injury.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37 HD037985, R01 AR048212, R01 AR046386, R01 HD087459, P30 GM103333, F30 HD096830). JJC’s work on this study was also supported, in part, by the Foundation for Physical Therapy Research Promotion of Doctoral Studies (PODS) Level I and Level II Scholarships. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge Drs Wendy Hurd, Erin Hartigan, Stephanie Di Stasi, Andrew Lynch, David Logerstedt, and Kathleen Cummer for their assistance with data collection and the University of Delaware Physical Therapy Clinic for providing the physical therapy treatments for the research participants in this study. They also thank Martha Callahan and the Delaware Rehabilitation Institute’s Clinical

Research Core (http://www.udel.edu/dri/ResCore.html) for their assistance with patient recruitment, scheduling, and data management.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, et al. Sport-specific yearly risk and incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears in high school athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2716–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chmielewski TL, Rudolph KS, Fitzgerald GK, et al. Biomechanical evidence supporting a differential response to acute ACL injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2001;16:586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommerfeldt M, Raheem A, Whittaker J, et al. Recurrent instability episodes and meniscal or cartilage damage after anterior cruciate ligament injury: A systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(7):2325967118786507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart HF, Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, et al. Knee kinematics and joint moments during gait following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(10):597–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slater LV, Hart JM, Kelly AR, Kuenze CM. Progressive changes in walking kinematics and kinetics after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction: A review and meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2017;52(9):847–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail SA, Button K, Simic M, et al. Three-dimensional kinematic and kinetic gait deviations in individuals with chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficient knee: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2016;35:68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1756–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wellsandt E, Gardinier ES, Manal K, et al. Decreased knee joint loading associated with early knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2015;44(1):143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teng HL, Wu D, Su F, et al. Gait characteristics associated with a greater increase in medial knee cartilage T1rho and T2 relaxation times in patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(14):3262–3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar D, Su F, Wu D, et al. Frontal plane knee mechanics and early cartilage degeneration in people with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A longitudinal study. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(2):378–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jomha NM, Borton DC, Clingeleffer AJ, Pinczewski LA. Long-term osteoarthritic changes in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(358):188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Church S, Keating JF. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: Timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1639–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson KJ. Timing of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in athletes and the incidence of secondary pathology within the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(3):362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TO, Postle K, Penny F, et al. Is reconstruction the best management strategy for anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction versus non-operative treatment. The Knee. 2014;21:462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, et al. A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2509–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellsandt E, Failla MJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Does anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction improve functional and radiographic outcomes over nonoperative management 5 years after injury? Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(9):2103–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Stasi SL, Snyder-Mackler L. The effects of neuromuscular training on the gait patterns of ACL-deficient men and women. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2012;27(4):360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgoulis AD, Papadonikolakis A, Papageorgiou CD, et al. Three-dimensional tibiofemoral kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient and reconstructed knee during walking. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartigan EH, Zeni J, Di Stasi S, et al. Preoperative predictors for noncopers to pass return to sports criteria after ACL reconstruction. Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2012;28:366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, et al. Walking gait asymmetries 6 months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction predict 12-month patient-reported outcomes. J Orthop Res. 2018;36(11):2932–2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, et al. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):632–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1(3–4):226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartigan E, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Perturbation training prior to ACL reconstruction improves gait asymmetries in non-copers. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(6):724–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A progressive 5-week exercise therapy program leads to significant improvement in knee function early after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(11):705–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartigan EH, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Time line for noncopers to pass return-to-sports criteria after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(3):141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, et al. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(8):1132–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams DL, Logerstedt DS, Hunter-Giordano A, et al. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012; 42(7):601–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardinier ES, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Altered loading in the injured knee after ACL rupture. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(3):458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Stasi SL, Hartigan EH, Snyder-Mackler L. Unilateral stance strategies of athletes with ACL deficiency. Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2012;28:374–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardinier ES, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Gait and neuromuscular asymmetries after acute ACL rupture. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(8):1490–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchanan TS, Lloyd DG, Manal K, Besier TF. Neuromusculoskeletal modeling: Estimation of muscle forces and joint moments and movements from measurements of neural command. J Appl Biomech. 2004;20(4):367–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manal K, Buchanan TS. An electromyogram-driven musculoskeletal model of the knee to predict in vivo joint contact forces during normal and novel gait patterns. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135(2):021014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delp SL, Loan JP, Hoy MG, et al. An interactive graphics-based model of the lower extremity to study orthopaedic surgical procedures. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1990;37:757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khandha A, Manal K, Wellsandt E, et al. Gait mechanics in those with/without medial compartment knee osteoarthritis five years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(3):625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snyder-Mackler L, Delitto A, Stralka SW, Bailey SL. Use of electrical stimulation to enhance recovery of quadriceps femoris muscle force production in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 1994;74(10):901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, Crossley KM, Roos EM. Measures of knee function: International knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score physical function short form (KOOS-PS), knee ou. Arthritis care & research. 2011;63 Suppl 1:S208–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(2):88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardinier ES, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Minimum detectable change for knee joint contact force estimates using an EMG-driven model. Gait and Posture. 2013;38:1051–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Vol 2nd ; 1988:567–567. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wellsandt E, Zeni JA, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Hip joint biomechanics in those with and without post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2017;50:63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wellsandt E, Khandha A, Manal K, et al. Predictors of knee joint loading after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(3):651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khandha A, Manal K, Capin J, et al. High muscle co-contraction does not result in high joint forces during gait in anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees. J Orthop Res. 2019;37(1):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT, Harkey MS, et al. Greater mechanical loading during walking is associated with less collagen turnover in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(2):425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oiestad BE, Holm I, Risberg MA. Return to pivoting sport after ACL reconstruction: Association with osteoarthritis and knee function at the 15-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(18):1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andriacchi TP, Mundermann A, Smith RL, et al. A framework for the in vivo pathomechanics of osteoarthritis at the knee. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32(3):447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang C, Tashiro Y, Lynch A, et al. Kinematics and arthrokinematics in the chronic ACL-deficient knee are altered even in the absence of instability symptoms. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(5):1406–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capin JJ, Khandha A, Zarzycki R, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Gait mechanics after ACL reconstruction differ according to medial meniscal treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(14):1209–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ismail SA, Simic M, Salmon LJ, et al. Side-to-side differences in varus thrust and knee abduction moment in high-functioning individuals with chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markstrom JL, Tengman E, Hager CK. ACL-reconstructed and ACL-deficient individuals show differentiated trunk, hip, and knee kinematics during vertical hops more than 20 years post-injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(2):358–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewek MD, Chmielewski TL, Risberg MA, Snyder-Mackler L. Damic knee stability after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31(4):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.