ABSTRACT

Nociceptor sensitization following nerve injury or inflammation leads to chronic pain. An increase in the nociceptor hyperpolarization-activated current, Ih, is observed in many models of pathological pain. Pharmacological blockade of Ih prevents the mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity that occurs during pathological pain. Alterations in the Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated ion channel 2 (HCN2) mediate Ih-dependent thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia. Limited knowledge exists regarding the nature of these changes during chronic inflammatory pain. Modifications in HCN2 expression and post-translational SUMOylation have been observed in the Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) model of chronic inflammatory pain. Intra-plantar injection of CFA into the rat hindpaw induces unilateral hyperalgesia that is sustained for up to 14 days following injection. The hindpaw is innervated by primary afferents in lumbar DRG, L4-6. Adjustments in HCN2 expression and SUMOylation have been well-documented for L5 DRG during the first 7 days of CFA-induced inflammation. Here, we examine bilateral L4 and L6 DRG at day 1 and day 3 post-CFA. Using L4 and L6 DRG cryosections, HCN2 expression and SUMOylation were measured with immunohistochemistry and proximity ligation assays, respectively. Our findings indicate that intra-plantar injection of CFA elicited a bilateral increase in HCN2 expression in L4 and L6 DRG at day 1, but not day 3, and enhanced HCN2 SUMOylation in ipsilateral L6 DRG at day 1 and day 3. Changes in HCN2 expression and SUMOylation were transient over this time course. Our study suggests that HCN2 is regulated by multiple mechanisms during CFA-induced inflammation.

KEYWORDS: HCN2, CFA, SUMO, inflammation, DRG

Introduction

Persistent inflammation and/or nerve injury can lead to chronic pain. This debilitating condition is characterized by allodynia (pain in response to non-noxious stimuli), hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli), and spontaneous painful and/or burning sensations in the absence of stimuli [1–6]. Chronic pain is underpinned by widespread reorganization of the pain circuitry, including changes to component neurons. While component neurons throughout the pain circuit can be altered [7–9], here we focus specifically upon nociceptors.

Nociceptors are peripheral sensory neurons that initiate pain signaling upon detecting noxious temperatures, pressures and chemicals [2]. Nociceptor somata are located in the Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia. A single process projects from the soma; it bifurcates, and one process extends to the periphery and the other innervates the central nervous system. Nociceptors are functionally classified by their conduction velocities: C-fibers have small-diameter, unmyelinated axons; Aδ nociceptors have small to medium diameter, lightly myelinated axons; and, there is also a class of A- β nociceptors that have larger diameter myelinated axons [10,11]. The range of conduction velocities for each of these 3 classes varies with the species, but for the sake of comparison, the peak conduction velocities for C-, Aδ- and A β -fibers in a typical guinea pig compound action potential are approximately 0.6 m/s, 3.3 m/s and 9.6 m/s, respectively [10]. Neurons within each class are functionally subdivided according to their threshold to noxious chemical, mechanical, and thermal stimuli. Recently, unbiased RNA sequencing approaches have been included in classification schemes [12,13], and several principal nociceptor cell types have been identified, each with a unique transcriptome, size and sensory function.

Nociceptors become hyper-excitable in chronic pain states elicited by nerve damage (neuropathic pain) and/or persistent, unresolved inflammation (inflammatory pain). This sensitization not only changes nociceptor responses to noxious and non-noxious stimuli, but also drives pathological changes to CNS components of the pain circuitry. Nociceptor sensitization is due, in part, to persistent alterations in a number of ionic currents that act to reduce threshold and increase cell excitability [14–19]. The hyperpolarization-activated, nonspecific cation current, Ih, is a slowly depolarizing current that functions to enhance nociceptor excitability [20]. Under normal conditions, Ih plays a limited role in pain transmission, and pain thresholds are largely unaffected by pharmacological inhibition or genetic ablation of Ih [21–23]. However, during sensitization, Ih transitions into a pivotal role in pain signaling. In multiple models of chronic pain, nociceptor Ih amplitude is increased, and pharmacological agents that block Ih reduce nociceptor excitability and return pain thresholds to baseline [4,14,21,24–33]. In addition, blocking Ih during chronic pain can also reduce the release of inflammatory mediators and glial activation [34].

The family of hyperpolarization activated, cyclic nucleotide gated ion channels, isoforms 1–4 (HCN 1–4), mediate Ih. These pore-forming α-subunits are assembled into homo- and hetero-tetrameric channels that are largely permeable to K+ and Na+, and may also display a small permeability for Ca2+ [35,36]. Channels open upon hyperpolarization, but isoforms differ in their activation kinetics: HCN1 is the fastest and HCN4 is the slowest. All isoforms possess a cyclic nucleotide binding domain (CNBD), which when bound by cAMP shifts the voltage dependence of activation to more positive potentials. Isoforms show varying degrees of cAMP sensitivity, with HCN2 and HCN4 exhibiting the largest depolarizing shift in voltage dependence upon binding cAMP. Homo- and hetero-tetrameric channels composed largely of HCN1 and HCN2, and to a lesser extent, HCN3, conduct nociceptor Ih [28,37,38].

Studies utilizing genetic ablation of specific HCN isoforms have begun to identify isoform-specific contributions to chronic pain. HCN1 contributes to cold allodynia during neuropathic pain [39]. HCN2 [21,22], but not HCN1 [39] or HCN3 [40] contributes to mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia; however, the role of HCN2 varies with the model under study. When Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) was injected into the plantar surface of the hindpaw to elicit persistent inflammation, HCN2 knock out in sensory afferent neurons prevented mechanical but not thermal hyperalgesia on day 3 post-CFA [21]. In contrast, ablation of HCN2 in sensory afferents prevented thermal but not mechanical hyperalgesia from 30 min to 3 hr after intra-plantar injection of the potent inflammatory mediator, PGE2 [22]. Moreover, genetic ablation of HCN2 in primary sensory afferents prevented both mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia from 2 to 21 days after the induction of neuropathic pain by chronic constriction of the sciatic nerve [22]. Loss of HCN2 in primary sensory afferents also significantly reduced the pain behavior that is typically observed 1 hr after intra-plantar injection of 4% formalin (licking, biting and paw lifting), and that is thought to be due to release of inflammatory mediators [22]. These data suggest that there are likely to be numerous mechanisms that regulate HCN2 channels over multiple time courses, and that each mechanism may be differentially activated in a cell-type-specific manner and according to the catalyst(s) that triggers the pain state.

Current analgesic strategies to reduce Ih focus mainly on the development of isoform selective HCN channel blockers, e.g. small molecules that preferentially block channels containing HCN1 and/or HCN2 subunits [41,42]. More generally, knowledge about the molecular mechanisms that alter ionic currents during pathological pain is being exploited to develop novel anti-nociceptive drugs tailored to a specific modulatory mechanisms [43,44]. Several intracellular signaling pathways are known to drive nociceptor sensitization [45–48], but details on their modulation of HCN2 channels are limited.

A variety of molecular mechanisms may underpin the increase in nociceptor Ih during chronic pain states. Altered nociceptor HCN2 channel expression has been observed in multiple subcellular compartments during pathological pain, including the soma, peripheral terminals, central terminals, and along axons in nerves [21,28,49–51]. In some models of neuropathic pain, somatic nociceptor HCN2 protein expression appeared to decrease despite an increased Ih [27,52,53]. In these cases, the decrease in expression may represent compensation for prolonged nociceptor hyperexcitability, or redistribution of the channels from soma to axon. In other models of inflammatory pain, both Ih and HCN2 protein expression increased [21,28,29,49–51,54,55]. In most instances, it was not clear if altered expression represented an adjustment to transcription, translation, and/or post-translational modifications that modify channel turnover. The rat model of CFA-induced chronic inflammatory pain highlights the idea that multiple mechanisms may be regulating HCN2 channels over different time courses. Unilateral, intra-plantar CFA injection elicits persistent inflammation and chronic pain in the ipsilateral hindlimb that is resolved by 14–21 days [56,57]. HCN2 expression is enhanced in multiple subcellular compartments leading to mechanical hyperalgesia [21,28,49,51]. A detailed immunohistochemical examination of somatic HCN2 protein expression in lumbar 5 (L5) DRG neurons that innervate the hindlimb showed that HCN2 immunoreactivity significantly increased on day 1 post-CFA in small and medium neurons relative to control animals that did not receive CFA injections [55]. HCN2 staining intensity then returned to baseline by day 3, but the number of neurons expressing HCN2 significantly increased [55]. By days 5–7 post-CFA, HCN2 staining intensity was once again significantly increased, and the number of neurons expressing HCN2 remained elevated relative to controls [28]. In these studies, DRG neurons were only identified by soma size, and it is not known if all changes occurred in one cell type, or if HCN2 expression was altered in different cell types at distinct time points. It is noteworthy that changes in somatic HCN2 protein expression on days 1 and 3 post-CFA were bilateral, while chronic pain only occurs in the ipsilateral hindlimb [21,57]. This suggest that an increase in HCN2 protein expression may be necessary, but that the supplemental channels are not sufficient to produce pathological pain. One possibility is that a second ipsilateral mechanism acts on the supplemental HCN2 channels to alter their function and/or subcellular location.

It is well documented that HCN2 channel function is regulated by cAMP. Binding of cAMP to the channel’s CNBD significantly shifts voltage dependence to more positive potentials, which will increase Ih under physiological conditions. DRG cAMP levels are elevated in models of chronic pain, and enhanced cAMP concentrations lower nociceptive thresholds and lead to hyperalgesia [4,25,58]. Agonists of Gi/o-coupled receptors that reduce cAMP produce analgesia [59]. In some models of neuropathic pain, genetic ablation of PKA had no effect on hyperalgesia, suggesting that direct binding of cAMP to the channel CNBD could increase Ih [60,61]. In contrast, PKA is necessary for CFA-induced inflammatory pain [61]. Knocking out either HCN2 or PKA prevented CFA-induced pathological pain, but deletion of the CNBD domain from the HCN2 channel had no effect on pain thresholds [61]. Furthermore, on days 5–7 post-CFA, C-fiber but not Aδ nociceptors showed enhanced excitability due to a significant increase in Ih activation kinetics and amplitude, but there was no change in Ih voltage dependence of activation [28,62]. PKA is known to phosphorylate HCN2 [61]. Thus, the existing data suggest that CFA-induced persistent inflammation triggers cAMP activation of PKA, and perhaps, PKA phosphorylation of HCN2, which somehow leads to an increase in Ih.

HCN2 α-subunits interact with several auxiliary subunits that modify channel function, stability and surface expression [63–68]. Protein-protein interactions can be regulated by post-translational SUMOylation [69]. Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier (SUMO) peptides are post-translationally conjugated to lysine residues on target proteins, e.g. HCN2. The SUMO moiety can then promote or prevent interactions between the target and its interacting partners. There are 4 SUMO isoforms (SUMO1-4): SUMO2 & SUMO3 (SUMO2/3) are ~97% identical; SUMO1 shares 47% identity with SUMO2/3; the physiological relevance of SUMO 4 is unclear. The majority of SUMOylation (~65%) occurs within identifiable consensus sequences [70], and HCN2 has several putative SUMOylation sites [71]. HCN2 SUMOylation at K669 increased channel surface expression and Ih maximal conductance in a heterologous expression system [71]. Inflammation causes a global increase in the SUMOylation of DRG proteins, and experimentally enhanced SUMOylation in sensory neurons produced pathological pain [72]. In a rat model of CFA-induced inflammatory pain, HCN2 SUMOylation was increased in small DRG neurons on days 1 and 3 post-CFA (later times not examined) [55]. A target protein’s phosphorylation status often determines its ability to be SUMOylated [69,73]. Activation of the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP-PKA axis in an identified pattern generating neuron permitted the post-translational SUMOylation that led to an enhanced Ih [74]. Thus, inflammatory mediators acting through PKA could alter the phosphorylation status of HCN2 channels to permit their SUMOylation, which could enhance surface expression. SUMOylation of HCN2 channels is dynamically regulated as inflammation progresses. SUMO2/3 conjugation to HCN2 increased at day 1 post-CFA, and SUMO1 conjugation to HCN2 increased at day 3 post-CFA [55]. These data imply that inflammatory mediators regulate HCN2 interaction with components of the SUMOylation machinery that show target and SUMO-isoform specificity [69].

The rat hindpaw is innervated by sensory neurons in L4-L6 DRG. We previously reported the effects of CFA injection on HCN2 expression and SUMOylation in L5 DRG. Here, we complete the study and document changes in HCN2 expression and SUMOylation in L4 and L6.

Materials and methods

Animal ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia State University and all experiments were performed in compliance with the Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). 60-day old, male Sprague-Dawley rats were pair housed in a 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 hr) with ad libitum access to food and water.

CFA model and tissue preparation

A detailed description is found in Forster et al [55]. Briefly, 60-day old, male Sprague Dawley rats were injected with 200 µl of CFA into the mid-plantar surface of the right hindpaw. Control animals were handled, but not injected. 1 or 3 days later, animals were anesthetized, injected with heparin and perfused. Animals were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Bilateral L4 and L6 DRG were extracted and placed into an 18% sucrose solution at 4°C overnight. The following day, the epineurium was removed and DRG were embedded in 0.3% gelatin and sliced into 20 µm cryosections.

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies, dilution factors and applicable experiments are found in Forster et al [55].

Immunohistochemistry and analysis

IHC was performed as previously described [55]. For each DRG, three 5x magnification images were taken. Blind analysis was performed on Photoshop. Images were thresholded to remove the intensity of the sheath. All cells above threshold with a definitive nucleus and visible cell perimeter were HCN2+ cells. Cells below threshold but meeting these quantification requirements were considered HCN2-. HCN2+ cells were sorted into classes by diameter: small ≤ 30 µm, medium 30–40 µm and large > 40 µm. All gray mean values within a size class were averaged and is represented as the mean pixel intensity of that size class. The number of HCN2+ cells within a size class were divided by the sum of all HCN2+ and HCN2- cells and is represented as the frequency of that class. IHC experiments were repeated on 6 or 7 experimental animals and 4 or 5 control animals for L4 and L6 DRG at day 1 and day 3.

Proximity ligation assay and analysis

PLAs were performed using Duolink® In Situ Red Kit and manufacturer’s guidelines as previously described [55]. Images were captured with a Zeiss 700 confocal microscope using a 40x oil immersion objective. Three cryosections were examined per DRG with a minimum of 3 z-stacks per cryosection. Blind analyses were performed using the FIJI version of ImageJ. Cells with a visible nucleus, clear cell boundaries and no overlap with neighboring cells or fibers were selected for quantification. Maximum intensity projections of 5 z-slices from the middle of the cells were created. Cells were outlined and thresholded using the triangle method. Watershed analysis divided coalesced signals. For each cell, the average number of puncta was divided by the cell area to obtain puncta/µm2. The mean pixel intensity (MPI) within 1 cell was processed by a program created by Alex Perez. PLA experiments were repeated on 6 experimental and 3 control DRG for L4 and L6 DRG at day 1 and day 3.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were preformed using GraphPad Prism. All data were tested for normality. The data for left and right DRG from each control animal were combined, because paired t-tests indicated left and right DRG showed no significant differences. IHC data were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc or Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post-hoc. Multiple comparison tests showed no significant differences in HCN2 SUMOylation between control and experimental DRG, therefore control data are not shown. Normal PLA data were measured using paired t-tests between ipsilateral and contralateral DRG. Non-parametric PLA data were analyzed with Wilcoxon-matched pairs. All values are presented as mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HCN2 expression and SUMOylation in L4 DRG neurons on days 1 and day 3 post-CFA

CFA was injected into the right hindpaw of experimental animals to elicit persistent inflammation, while control animals were handled, but not injected. Bilateral L4 and L6 DRG were dissected at day 1 or day 3 post-CFA and cryosectioned for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or proximity ligation assays (PLA), as previously described [55]. The IHC experiments were used to measure the level of HCN2 expression in a given cell (mean pixel intensity) and the percent of HCN2 expressing cells (frequency) in small (≤ 30 µm), medium (30–40 µm) and large (> 40 µm) neurons. Values for left and right control DRG were not significantly different from each other; therefore, left and right values were combined and the datum for one control animal represents the average for left and right DRG. PLA experiments measured the number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels (puncta/µm2) or the extent to which HCN2 channels were SUMOylated (puncta intensity) in ipsilateral relative to contralateral DRG.

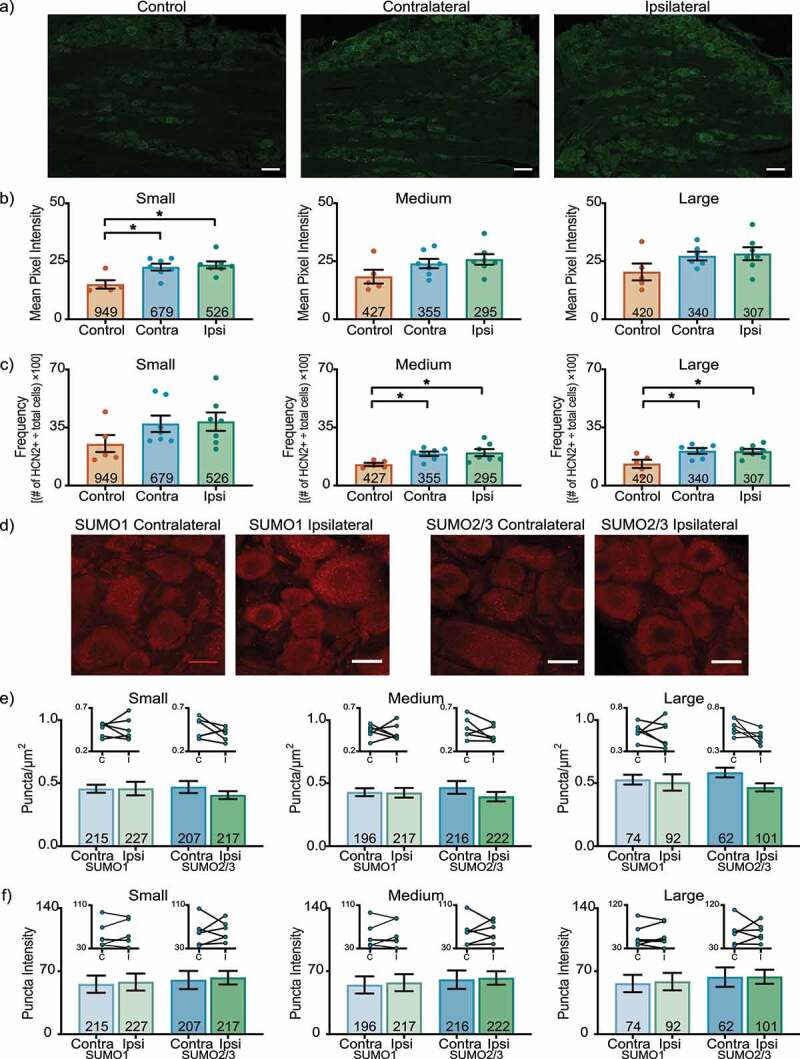

Figure 1 shows representative cryostat sections and the results for L4 DRG 1 day post-CFA. A significant ~53% increase in HCN2 IR was observed in both ipsilateral and contralateral small cells relative to control (contralateral: 22.5 ± 1.5; ipsilateral: 23.4 ± 1.5; control: 15.0 ± 1.8) (Figure 1(b)). There were no significant differences in medium or large cell IR (Medium contralateral: 24.0 ± 2.0; ipsilateral: 25.8 ± 2.3; control: 18.4 ± 3.0) (Large contralateral: 27.2 ± 1.9; ipsilateral: 28.2 ± 2.8; control: 20.4 ± 3.6). In contrast, Figure 1(c) shows that CFA-injection produced a bi-lateral increase in the number of medium and large, but not small cells expressing HCN2 (Small contralateral: 37.3 ± 5.0; ipsilateral: 38.6 ± 5.6; control: 25.0 ± 5.5) (Medium contralateral: 19.1 ± 1.3; ipsilateral: 19.9 ± 2.1; control: 12.7 ± 1.0) (Large contralateral: 20.8 ± 1.7; ipsilateral: 20.6 ± 1.5; control: 13.1 ± 2.5). These experiments did not reveal any CFA-induced change in post-translational SUMOylation of HCN2 channels. There were no significant differences in the number or intensity of puncta between ipsilateral and contralateral L4 DRG 1 day post-CFA for any size class (Figure 1(e,f)).

Figure 1.

HCN2 protein expression but not SUMOylation is altered in the L4 DRG 1 day post-CFA. (a) Representative images of HCN2 IR. Scale bars are 100 µm. (b) HCN2 mean pixel intensity is elevated in small diameter DRG neurons. Average mean pixel intensity ± SEM is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). Each dot represents the mean for one animal. Note that data for left and right DRG from each control were combined, because paired t-tests indicated left and right DRG showed no significant differences. The total number of cells examined for all animals within the treatment group is indicated in the bar. Asterisks indicate significance, *p < 0.05. Small cells: Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test (2,16) = 7.750; p = 0.014; medium cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,16) = 2.378; p = 0.125; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 2.158; p = 0.150. (c) The percent of medium and large diameter neurons expressing HCN2 increases 1 day post-CFA. Plot of percent HCN2 positive cells for each size class (frequency = # HCN2 positive cells for that size class ÷ total cell number for all classes). Bars indicate mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significance, *p < 0.05. Small cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,16) = 3.441; p = 0.184; medium cells: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test F(2,16) = 4.901; p = 0.022; large cells: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test F(2,15) = 5.188; p = 0.019. (d) Representative confocal projections (5 µm) from PLA experiments. Scale bars are 25 µm. (e) The number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels is unaltered 1 day post-CFA. The number of puncta/µm2 for HCN2 SUMO1 (light bars) and SUMO2/3 (dark bars) conjugation is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). SUMO1; small: 0.458 ± 0.054 vs 0.456 ± 0.032, p = 0.979, paired t-test; medium: 0.424 ± 0.038 vs 0.429 ± 0.032, p > 0.999, Wilcoxon-matched pairs; large: 0.505 ± 0.065 vs 0.528 ± 0.039, p = 0.740, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 0.405 ± 0.031 vs 0.469 ± 0.048, p = 0.271, paired t-test; medium: 0.394 ± 0.037 vs 0.467 ± 0.050, p = 0.181, paired t-test; large: 0.467 ± 0.032 vs 0.584 ± 0.038, p = 0.068, paired t-test. Inset: compares the means for contralateral and ipsilateral DRG for each animal. (f) SUMOylated HCN2 Puncta Intensities are unaltered 1 day post-CFA. Plot of average puncta intensity ± SEM for each size class. SUMO1; small: 57.86 ± 9.486 vs 55.55 ± 9.556, p = 0.615, paired t-test; medium: 57.24 ± 9.442 vs 54.76 ± 9.484, p = 0.643, paired t-test; large: 58.37 ± 9.707 vs 56.34 ± 9.626, p = 0.679, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 62.71 ± 7.576 vs 60.19 ± 10.08, p = 0.785, paired t-test; medium: 62.44 ± 7.471 vs 60.60 ± 10.21, p = 0.824, paired t-test; large: 63.80 ± 7.816 vs 63.46 ± 10.79, p = 0.975, paired t-test

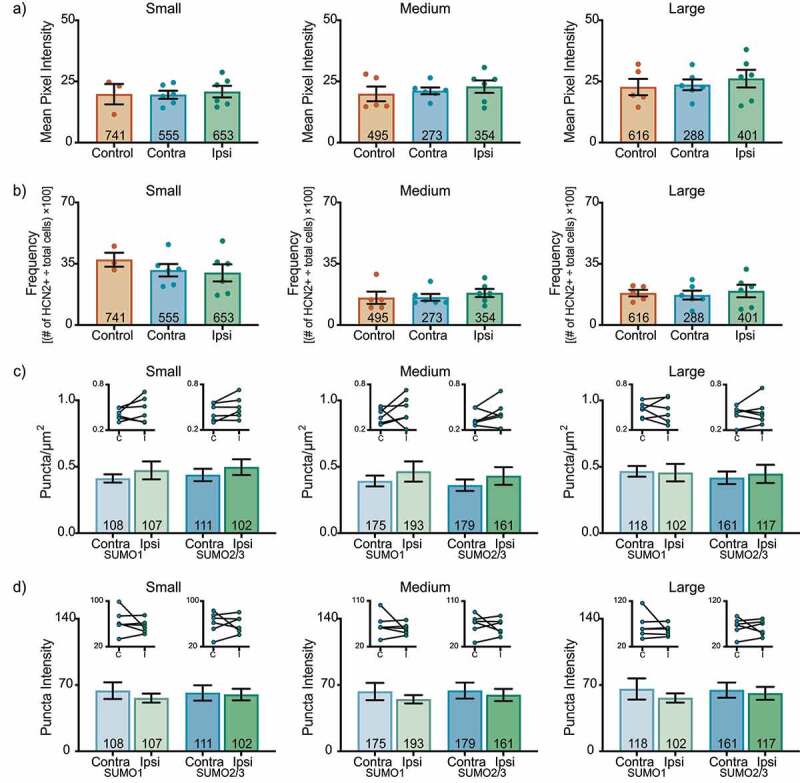

These experiments did not reveal any CFA-induced change in HCN2 expression or post-translational SUMOylation in L4 DRG on day 3 post-CFA. There were no significant differences in HCN2 mean pixel intensity (Figure 2(a)) or frequency (Figure 2(b)) for any size class. The number (Figure 2(c)) and intensity (Figure 2(d)) of puncta were similar in ipsilateral and contralateral L4 DRG.

Figure 2.

HCN2 protein expression and HCN2 SUMOylation are unaltered in the L4 DRG 3 days post CFA. (a) HCN2 mean pixel intensities do not change 3 days post-CFA. Average mean pixel intensity ± SEM is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). Each dot represents the mean for one animal. Note that data for left and right DRG from each control were combined, because paired t-tests indicated left and right DRG showed no significant differences. The total number of cells examined for all animals within the treatment group is indicated in the bar. Small cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,12) = 0.090; p = 0.915; medium cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,14) = 0.438; p = 0.819; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,14) = 0.330; p = 0.725. (b) The percent of HCN2 expressing cells does not change 3 days post-CFA. Plot of percent HCN2 positive cells for each size class (frequency = # HCN2 positive cells for that size class ÷ total cells number for all classes). Bars are mean ± SEM. Small cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,12) = 0.581; p = 0.574; medium cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,14) = 1.358; p = 0.531; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,14) = 0.176; p = 0.840. (c) The number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels is unaltered in L4 DRG neurons. The number of puncta/µm2 for HCN2 SUMO1 (light bars) and SUMO2/3 (dark bars) conjugation is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). SUMO1; small: 0.473 ± 0.068 vs 0.412 ± 0.031, p = 0.307, paired t-test; medium: 0.465 ± 0.076 vs 0.393 ± 0.041, p = 0.418, paired t-test; large: 0.456 ± 0.066 vs 0.466 ± 0.040, p = 0.847, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 0.479 ± 0.059 vs 0.438 ± 0.047, p = 0.121, paired t-test; medium: 0.431 ± 0.067 vs 0.361 ± 0.043, p = 0.236, paired t-test; large: 0.446 ± 0.069 vs 0.417 ± 0.047, p = 0.562, paired t-test. Inset: compares the means for contralateral and ipsilateral DRG for each animal. (d) SUMOylated HCN2 Puncta Intensities are unaltered in L4 DRG neurons. Plot of average puncta intensity ± SEM for each size class. SUMO1; small: 56.16 ± 4.766 vs 64.04 ± 8.799, p = 0.382, paired t-test; medium: 54.92 ± 4.379 vs 63.08 ± 9.142, p = 0.400, paired t-test; large: 56.32 ± 4.917 vs 65.79 ± 11.18, p = 0.423, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 59.62 ± 6.125 vs 61.62 ± 8.081, p = 0.836, paired t-test; medium: 59.44 ± 6.444 vs 64.02 ± 8.447, p = 0.609, paired t-test; large: 61.18 ± 6.817 vs 64.59 ± 7.984, p = 0.691, paired t-test

HCN2 expression and SUMOylation in L6 DRG neurons on days 1 and day 3 post-CFA

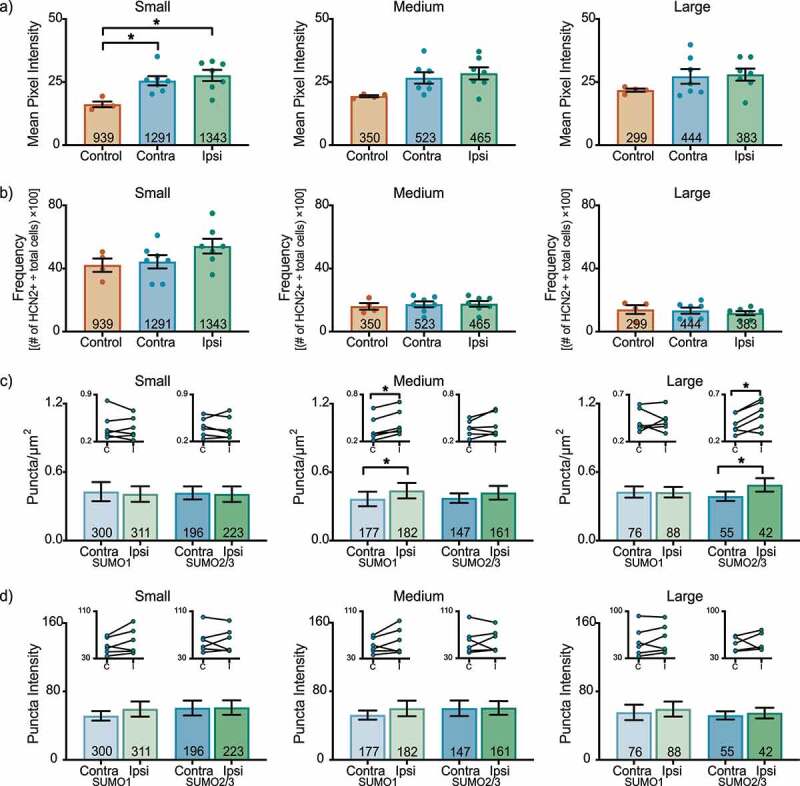

In the L6 DRG 1 day post-CFA, HCN2 expression bilaterally increased in experimental small cells relative to controls (Figure 3(a)). The mean pixel intensity was ~65% greater for experimental compared to control animals (contralateral: 25.5 ± 1.8; ipsilateral: 27.6 ± 2.2; control: 16.1 ± 1.1). Although mean pixel intensity increased in experimental vs. control for both medium and large cells, it was not statistically significant. There were no significant changes in HCN2 frequency for any size class (Small contralateral: 44.3 ± 4.2; ipsilateral: 54.1 ± 4.7; control: 42.1 ± 4.2) (Medium contralateral: 17.3 ± 1.9; ipsilateral: 17.6 ± 1.8; control: 16.0 ± 2.1) (Large contralateral: 13.3 ± 1.9; ipsilateral: 11.7 ± 1.3; control: 14.0 ± 2.8) (Figure 3(b)). There was a small but significant increase in the number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels in medium and large neurons (Figure 3(c)). The differences were isoform specific with SUMO 1 vs. SUMO 2/3 modification increasing in medium vs. large cells, respectively. There were no significant changes in puncta intensity (Figure 3(d)).

Figure 3.

HCN2 protein expression and HCN2 SUMOylation are enhanced in the L6 DRG 1 day post-CFA. (a) HCN2 mean pixel intensity is elevated in small diameter neurons. Average mean pixel intensity ± SEM is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). Each dot represents the mean for one animal. Note that data for left and right DRG from each control were combined, because paired t-tests indicated left and right DRG showed no significant differences. The total number of cells examined for all animals within the treatment group is indicated in the bar. Asterisks indicate significance, *p < 0.05. Small cells: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc F(2,15) = 7.422; p = 0.0060; medium cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 3.542; p = 0.055; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 1.338; p = 0.292. (b) The percent of HCN2 expressing cells is unaltered 1 day post-CFA. Plot of percent HCN2 positive cells for each size class (frequency = # HCN2 positive cells for that size class ÷ total cells number for all classes). Bars indicate mean ± SEM. Small cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 1.980; p = 0.173; medium cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 0.147; p = 0.865; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 0.365; p = 0.700. (c) The number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels increases in medium and large diameter neurons. The number of puncta/µm2 for HCN2 SUMO1 (light bars) and SUMO2/3 (dark bars) conjugation is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). Bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significance, *p < 0.05. SUMO1; small: 0.408 ± 0.068 vs 0.429 ± 0.083, p = 0.574, paired t-test; medium: 0.438 ± 0.068 vs 0.365 ± 0.064, p = 0.031, Wilcoxon matched-pairs; large: 0.424 ± 0.046 vs 0.426 ± 0.049, p = 0.961, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 0.407 ± 0.069 vs 0.418 ± 0.057, p = 0.752, paired t-test; medium: 0.419 ± 0.060 vs 0.372 ± 0.042, p = 0.189, paired t-test; large: 0.488 ± 0.059 vs 0.388 ± 0.042, p = 0.018, paired-test. Inset: compares the means for contralateral and ipsilateral DRG for each animal. (d) SUMOylated HCN2 Puncta Intensities are unaltered 1 day post-CFA. Plot of average puncta intensity ± SEM for each size class. SUMO1; small: 59.42 ± 8.867 vs 51.48 ± 5.557, p = 0.137, paired t-test; medium: 59.92 ± 9.085 vs 52.20 ± 5.315, p = 0.189, paired t-test; large: 59.39 ± 8.740 vs 55.49 ± 9.037, p = 0.316, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 61.16 ± 8.501 vs 60.61 ± 8.770, p = 0.916, paired t-test; medium: 60.58 ± 8.002 vs 60.13 ± 9.115, p = 0.936, paired t-test; large: 54.74 ± 6.259 vs 51.96 ± 4.790, p = 0.655, paired t-test

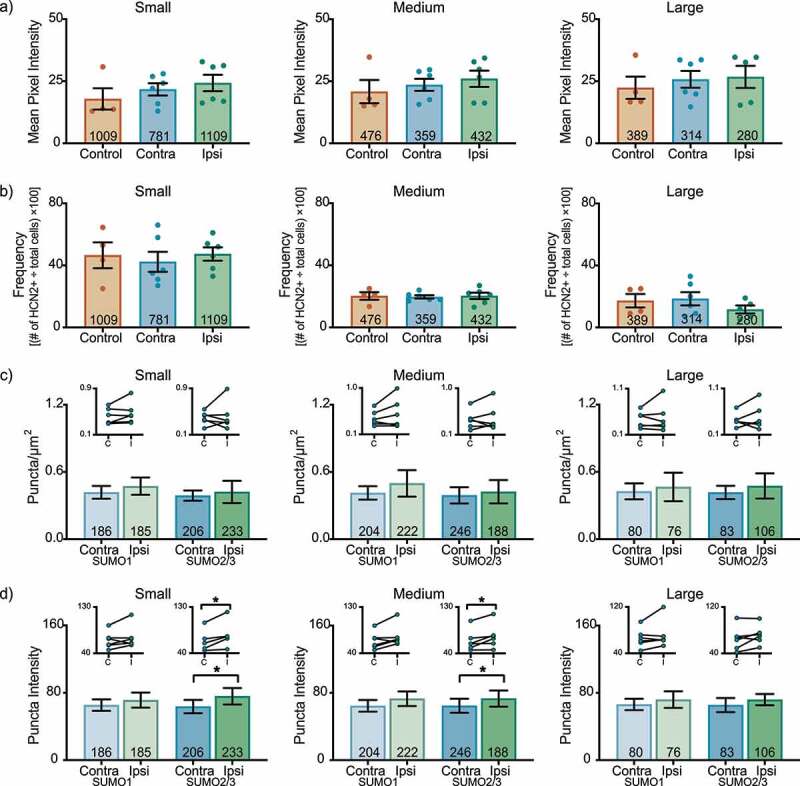

In the L6 DRG on day 3 post-CFA, there were no significant differences in HCN2 immunoreactivity (Figure 4(a)) or frequency (Figure 4(b)) for any L6 DRG neuronal size class. There were no significant changes in the number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels (Figure 4(c)). In contrast, HCN2 SUMO2/3 puncta intensity was significantly increased in ipsilateral small and medium cells, but not in large cells (Figure 4(d)).

Figure 4.

HCN2 SUMOylation but not protein expression is altered in the L6 DRG 3 days post-CFA. (a) HCN2 mean pixel intensities do not change 3 days post-CFA. Average mean pixel intensity ± SEM is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). Each dot represents the mean for one animal. Note that data for left and right DRG from each control were combined, because paired t-tests indicated left and right DRG showed no significant differences. The total number of cells examined for all animals within the treatment group is indicated in the bar. Small cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,13) = 2.842; p = 0.252; medium cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,13) = 1.309; p = 0.543; large cells: Kruskal-Wallis (2,12) = 0.061; p = 0.977. (b) The percent of HCN2 expressing cells does not change 3 days post-CFA. Plot of percent HCN2 positive cells for each size class (frequency = # HCN2 positive cells for that size class ÷ total cells number for all classes). Bars indicate mean ± SEM. Small cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,13) = 0.206; p = 0.817; medium cells: one-way ANOVA (2,13) = 0.043; p = 0.958; large cells: one-way ANOVA F(2,12) = 0.932; p = 0.420. (c) The number of HCN2 SUMOylated channels is unaltered 3 days post-CFA. The number of puncta/µm2 for HCN2 SUMO1 (light bars) and SUMO2/3 (dark bars) conjugation is shown for three size classes of DRG neurons (small: ≤ 30 µm; medium: 30–40 µm; large: > 40 µm). SUMO1; small: 0.473 ± 0.077 vs 0.418 ± 0.057, p = 0.211, paired t-test; medium: 0.498 ± 0.118 vs 0.413 ± 0.06, p = 0.219, paired t-test; large: 0.466 ± 0.127 vs 0.427 ± 0.071, p = 0.593, paired t-test; SUMO2/3; small: 0.423 ± 0.099 vs 0.389 ± 0.046, p = 0.678, paired t-test; medium: 0.424 ± 0.104 vs 0.392 ± 0.073, p = 0.563, Wilcoxon matched-pairs, large: 0.475 ± 0.112 vs 0.417 ± 0.059, p = 0.563, Wilcoxon matched-pairs. Inset: compares the means for contralateral and ipsilateral DRG for each animal. (d) SUMOylated HCN2 Puncta Intensities are increased in small and medium cells. Plot of average puncta intensity ± SEM for each size class. SUMO1; small: 71.29 ± 8.984 vs 65.37 ± 6.805, p = 0.219, Wilcoxon matched-pairs; medium: 73.03 ± 8.633 vs 64.59 ± 6.927, p = 0.094, Wilcoxon matched-pairs; large: 72.02 ± 9.835 vs 66.21 ± 6.770, p = 0.313, Wilcoxon matched-pairs; SUMO2/3; small: 75.83 ± 9.743 vs 63.63 ± 7.899, p = 0.031, Wilcoxon matched-pairs; medium: 73.25 ± 9.620 vs 64.71 ± 8.353, p = 0.046, paired t-test; large cells: 71.93 ± 6.724 vs 65.46 ± 8.374, p = 0.148, paired t-test

Discussion

In this work, we investigated HCN2 expression and SUMOylation in L4 and L6 DRG at days 1 and 3 post-CFA injection. Using IHC, we found a bilateral increase in HCN2 mean pixel intensity in small neurons from L4 and L6 DRG at day 1, but expression levels returned to baseline by day 3. The number of medium and large neurons expressing HCN2 also transiently increased in L4 DRG on day 1 post-CFA. Using PLA, we found that HCN2 SUMOylation increased in L6 DRG at days 1 and 3. The number of SUMOylated HCN2 channels increased in medium and large cells at day 1, whereas the extent of HCN2 SUMOylation was enhanced in small and medium cells at day 3.

The patterns of change in HCN2 expression and SUMOylation are distinct for each of the lumbar DRG (Tables 1 and 2). This is not surprising given that for each DRG a different fraction of neurons project to the hindpaw. Whereas most neurons in the L5 DRG project to the hindpaw [75,76], afferents in the L4 DRG project to the hindlimb, knee and hip joint [75,77,78], and the neurons in L6 DRG mainly innervate visceral organs [75,76,79]. Changes occurred in all size classes of neurons, which is consistent with the fact that both C-fiber and Aβ-fibers respond to CFA-induced inflammation [80].

Table 1.

Fold change in mean HCN2 expression in L4-L6 DRG

| Fold Change in Mean HCN2 Expression in Experimental DRG relative to Control DRG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCN2 Expression | Small | Medium | Large | |||

| Contralateral | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | Ipsilateral |

Contralateral | Ipsilateral | |

| Mean Pixel Intensity Day 1 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.5 (± 0.10) | 1.6 (± 0.10) | 1.3 (± 0.11) | 1.4 (± 0.12) | 1.3 (± 0.09) | 1.4 (± 0.14) |

| L5 | 1.4 (± 0.10) | 1.5 (± 0.12) | 1.3 (± 0.08) | 1.4 (± 0.14) | 1.2 (± 0.10) | 1.4 (± 0.19) |

| L6 | 1.6 (± 0.11) | 1.7 (± 0.14) | 1.4 (± 0.12) | 1.5 (± 0.12) | 1.3 (± 0.13) | 1.3 (± 0.11) |

| Frequency Day 1 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.5 (± 0.20) | 1.5 (± 0.22) | 1.5 (± 0.11) | 1.6 (± 0.17) | 1.6 (± 0.13) | 1.6 (± 0.11) |

| L5 | 1.7 (± 0.21) | 1.5 (± 0.25) | 1.0 (± 0.08) | 1.1 (± 0.15) | 0.8 (± 0.12) | 0.9 (± 0.25) |

| L6 | 1.1 (± 0.10) | 1.3 (± 0.11) | 1.1 (± 0.12) | 1.1 (± 0.11) | 1.0 (± 0.14) | 0.8 (± 0.10) |

| Mean Pixel Intensity Day 3 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.0 (± 0.08) | 1.1 (± 0.12) | 1.1 (± 0.07) | 1.1 (± 0.13) | 1.0 (± 0.10) | 1.2 (± 0.16) |

| L5 | 1.4 (± 0.20) | 1.3 (± 0.16) | 1.4 (± 0.22) | 1.3 (± 0.20) | 1.4 (± 0.25) | 1.3 (± 0.23) |

| L6 | 1.2 (± 0.14) | 1.4 (± 0.18) | 1.1 (± 0.12) | 1.2 (± 0.16) | 1.1 (± 0.15) | 1.2 (± 0.20) |

| Frequency Day 3 | ||||||

| L4 | 0.8 (± 0.10) | 0.8 (± 0.13) | 1.0 (± 0.12) | 1.2 (± 0.15) | 0.9 (± 0.14) | 1.1 (± 0.20) |

| L5 | 3.0 (± 0.70) | 2.6 (± 0.30) | 1.8 (± 0.17) | 1.7 (± 0.15) | 0.7 (± 0.21) | 1.0 (± 0.18) |

| L6 | 0.9 (± 0.14) | 1.0 (± 0.09) | 1.0 (± 0.05) | 1.0 (± 0.10) | 1.1 (± 0.25) | 0.7 (± 0.15) |

Bold values = p < 0.05

± SEM are shown in parenthesis.

Table 2.

Fold change in mean SUMOylation in L4-L6 DRG

| Fold Change in Mean HCN2 SUMOylation in Ipsilateral DRG relative to Contralateral DRG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCN2 SUMOylation | Small | Medium | Large | |||

| SUMO1 | SUMO2/3 | SUMO1 | SUMO2/3 | SUMO1 | SUMO2/3 | |

| Puncta/µm2 Day 1 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.0 (± 0.12) | 0.9 (± 0.07) | 1.0 (± 0.09) | 0.8 (± 0.08) | 1.0 (± 0.12) | 0.8 (± 0.05) |

| L5 | 0.8 (± 0.10) | 1.3 (± 0.17) | 0.7 (± 0.10) | 1.1 (± 0.10) | 0.7 (± 0.06) | 1.2 (± 0.16) |

| L6 | 1.0 (± 0.16) | 1.0 (± 0.16) | 1.2 (± 0.18) | 1.1 (± 0.16) | 1.0 (± 0.11) | 1.3 (± 0.15) |

| Puncta Intensity Day 1 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.0 (± 0.17) | 1.0 (± 0.13) | 1.0 (± 0.17) | 1.0 (± 0.13) | 1.0 (± 0.17) | 1.0 (± 0.12) |

| L5 | 0.9 (± 0.06) | 0.9 (± 0.09) | 1.1 (± 0.10) | 1.0 (± 0.10) | 1.0 (± 0.10) | 1.0 (± 0.11) |

| L6 | 1.2 (± 0.17) | 1.0 (± 0.14) | 1.1 (± 0.17) | 1.0 (± 0.13) | 1.1 (± 0.16) | 1.1 (± 0.12) |

| Puncta/µm2 Day 3 | ||||||

| L4 | 1.1 (± 0.16) | 1.1 (± 0.14) | 1.2 (± 0.19) | 1.2 (± 0.18) | 1.0 (± 0.14) | 1.1 (± 0.16) |

| L5 | 1.3 (± 0.13) | 1.1 (± 0.13) | 0.8 (± 0.20) | 1.0 (± 0.19) | 0.9 (± 0.18) | 1.0 (± 0.17) |

| L6 | 1.1 (± 0.18) | 1.1 (± 0.25) | 1.2 (± 0.29) | 1.1 (± 0.27) | 1.1 (± 0.30) | 1.1 (± 0.27) |

| Puncta Intensity Day 3 | ||||||

| L4 | 0.9 (± 0.07) | 1.0 (± 0.10) | 0.9 (± 0.07) | 0.9 (± 0.10) | 0.9 (± 0.08) | 0.9 (± 0.11) |

| L5 | 1.0 (± 0.03) | 1.0 (± 0.08) | 1.0 (± 0.03) | 1.0 (± 0.08) | 1.1 (± 0.03) | 1.1 (± 0.08) |

| L6 | 1.1 (± 0.14) | 1.2 (± 0.15) | 1.1 (± 0.13) | 1.1 (± 0.15) | 1.1 (± 0.15) | 1.1 (± 0.10) |

Bold values = p < 0.05

± SEM are shown in parenthesis.

Despite the fact that neurons in L4-L6 DRG differentially innervate the hindpaw, Table 1 shows that most changes in HCN2 expression occurred to the same extent in ipsi- and contra-lateral DRG for all 3 lumbar levels. This generalized change suggests that altered expression of HCN2 is likely to be a systemic response to CFA injection [81], which is not sufficient for the development of inflammatory pain at these time points. In contrast, Table 2 shows increased SUMOylation is observed exclusively in the ipsilateral side and may make a more direct contribution to the pain phenotype. In that respect, and given that SUMOylation of HCN2 is known to enhance surface expression of the channel [71], it may be that in DRGs where SUMOylation is increased, surface expression of HCN2 is also increased without necessarily altering total expression. Alternatively, SUMOylation of HCN2 may have a direct effect on the gating of the channel. There are several examples of SUMOylation altering ion channel biophysical properties [72,82–88]. In our previous study, enhanced HCN2 SUMOylation in HEK cells did not alter Ih voltage dependence or kinetics [71]. However, this result must be interpreted in the context of significant experimental caveats. First, since SUMO regulates protein-protein interactions, the effect of HCN2 SUMOylation will depend upon the available complement of interacting proteins, and the HCN2 interactome varies between cell types. Second, in our HEK cell experiments the level of HCN2 SUMOylation was altered in an uncontrolled fashion simply by increasing the cytosolic concentration of SUMO and the SUMO conjugating enzyme, ubc9. HCN2 has multiple putative SUMOylation sites, but this manipulation increased SUMOylation at just a single site, so all potential effects of enhanced SUMOylation may not have been observed. Third, modulators play a permissive role in SUMOylation [74], and the phosphorylation state of a protein determines which sites can be SUMOylated [69,73]. Thus, inflammatory mediators that alter phosphorylation states will likely produce a distinct pattern of HCN2 SUMOylation and associated effects that would not be replicated in the HEK cell experiments.

Emerging data suggest that altered SUMOylation may drive changes in several ion channels during nociceptor sensitization. The SUMOylation status of hundreds of proteins in a single cell is altered in response to a cellular stressor [70,89]. Chronic inflammation resulted in hyper-SUMOylation of the heat sensing TRPV1 channel, which lowered the temperature threshold of activation and led to thermal hyperalgesia [72]. CRMP2, a subunit of the NaV1.7 channel, is hyper-SUMOylated in a rat model of chronic neuropathic pain, which enhances the sodium current; and, blocking CRMP2 hyper-SUMOylation in DRG neurons prevented mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia [73,90–92]. A ~2-fold change in CRMP2 SUMOylation was observed in sciatic nerve, dorsal horn and glabrous skin during neuropathic pain [92] suggesting that larger changes in HCN2 SUMOylation may be observed in subcellular compartments such as axons and terminals relative to somata. Additional ion channels are known to be SUMOylated including Kv4 [82], Kv11 [83], Kv7 [84,93], Kv2 [94], K2P1 [85,95], Kv1.5 [86], NaV1.2 [87] and NaV1.5 [96]. Their SUMOylation patterns have not yet been ascertained during chronic pain.

In sum, CFA-induced inflammation results in HCN2-dependent mechanical hyperalgesia. Inflammation-induced alterations in lumbar DRG sensory neurons include altered HCN2 expression and post-translational SUMOylation. Multiple mechanisms regulate HCN2 during the time course of CFA-induced inflammation. Identification of these mechanisms and the cell type in which they occur are worth further study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our labmate Meghyn Welch for her continued support and feedback, and Alex Perez for his expertise in software development and creating a program to aid in data analysis.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Georgia State University with a Brains and Behavior Seed Grant to [DJB and AZM] and a Brains and Behavior fellowship to [LAF] and by NIH R03NS116327 to [DJB].

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA Jr., Chiu IM.. Nociceptor sensory neuron-immune interactions in pain and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2017. January;38(1):5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J Clin Invest. 2010. November;120(11):3760–3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Xu Q, Yaksh TL. A brief comparison of the pathophysiology of inflammatory versus neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011. August;24(4):400–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tsantoulas C, Mooney ER, McNaughton PA. HCN2 ion channels: basic science opens up possibilities for therapeutic intervention in neuropathic pain. Biochem J. 2016. September 15;473(18):2717–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Emery EC, Young GT, McNaughton PA. HCN2 ion channels: an emerging role as the pacemakers of pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012. August;33(8):456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kuner R, Flor H. Structural plasticity and reorganisation in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016. December 15;18(1):20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Du L, Wang SJ, Cui J, et al. Inhibition of HCN channels within the periaqueductal gray attenuates neuropathic pain in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2013. April;127(2):325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Du L, Wang SJ, Cui J, et al. The role of HCN channels within the periaqueductal gray in neuropathic pain. Brain Res. 2013. March;15(1500):36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boadas-Vaello P, Homs J, Reina F, et al. Neuroplasticity of supraspinal structures associated with pathological pain. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2017. August;300(8):1481–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Djouhri L, Lawson SN. Abeta-fiber nociceptive primary afferent neurons: a review of incidence and properties in relation to other afferent A-fiber neurons in mammals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004. October;46(2):131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nagi SS, Marshall AG, Makdani A, et al. An ultrafast system for signaling mechanical pain in human skin. Sci Adv. 2019. July;5(7):eaaw1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2015. January;18(1):145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li CL, Li KC, Wu D, et al. Somatosensory neuron types identified by high-coverage single-cell RNA-sequencing and functional heterogeneity. Cell Res. 2016. January;26(1):83–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tibbs GR, Posson DJ, Goldstein PA. Voltage-gated ion channels in the PNS: novel therapies for neuropathic pain? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016. July;37(7):522–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zemel BM, Ritter DM, Covarrubias M, et al. A-type KV channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons: diversity, function, and dysfunction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reichling DB, Levine JD. Critical role of nociceptor plasticity in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci. 2009. December;32(12):611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Berta T, Qadri Y, Tan PH, et al. Targeting dorsal root ganglia and primary sensory neurons for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017. July;21(7):695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gold MS, Gebhart GF. Nociceptor sensitization in pain pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2010. November;16(11):1248–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pace MC, Passavanti MB, De Nardis L, et al. Nociceptor plasticity: a closer look. J Cell Physiol. 2018. April;233(4):2824–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yagi J, Sumino R. Inhibition of a hyperpolarization-activated current by clonidine in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998. September;80(3):1094–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schnorr S, Eberhardt M, Kistner K, et al. HCN2 channels account for mechanical (but not heat) hyperalgesia during long-standing inflammation. Pain. 2014. June;155(6):1079–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Emery EC, Young GT, Berrocoso EM, et al. HCN2 ion channels play a central role in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Science. 2011. September 9;333(6048):1462–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Takasu K, Ono H, Tanabe M. Spinal hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels at primary afferent terminals contribute to chronic pain. Pain. 2010. October;151(1):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang X, Wang S, Wang W, et al. A novel intrinsic analgesic mechanism: the enhancement of the conduction failure along polymodal nociceptive C-fibers. Pain. 2016. October;157(10):2235–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsantoulas C, Lainez S, Wong S, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated 2 (HCN2) ion channels drive pain in mouse models of diabetic neuropathy. Sci Transl Med. 2017. September 27;9(409):eaam6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Luo L, Chang L, Brown SM, et al. Role of peripheral hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-modulated channel pacemaker channels in acute and chronic pain models in the rat. Neuroscience. 2007. February 23;144(4):1477–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chaplan SR, Guo HQ, Lee DH, et al. Neuronal hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels drive neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2003. February 15;23(4):1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Weng X, Smith T, Sathish J, et al. Chronic inflammatory pain is associated with increased excitability and hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in C- but not adelta-nociceptors. Pain. 2012. April;153(4):900–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Richards N, Dilley A. Contribution of hyperpolarization-activated channels to heat hypersensitivity and ongoing activity in the neuritis model. Neuroscience. 2015. January;22(284):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yao H, Donnelly DF, Ma C, et al. Upregulation of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci. 2003. March 15;23(6):2069–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dalle C, Eisenach JC. Peripheral block of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) reduces mechanical allodynia in animal models of postoperative and neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005. May–June;30(3):243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sun Q, Xing GG, Tu HY, et al. Inhibition of hyperpolarization-activated current by ZD7288 suppresses ectopic discharges of injured dorsal root ganglion neurons in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Brain Res. 2005. January 25;1032(1–2):63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lee DH, Chang L, Sorkin LS, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated, cation-nonselective, cyclic nucleotide-modulated channel blockade alleviates mechanical allodynia and suppresses ectopic discharge in spinal nerve ligated rats. J Pain. 2005. July;6(7):417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang H, Zhang Z, Huang D. Decreased HCN2 channel expression attenuates neuropathic pain by inhibiting pro-inflammatory reactions and NF-kappaB activation in mice. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(1):154–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wahl-Schott C, Biel M. HCN channels: structure, cellular regulation and physiological function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009. February;66(3):470–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sartiani L, Mannaioni G, Masi A, et al. The Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: from biophysics to pharmacology of a unique family of ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2017. October;69(4):354–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gao LL, McMullan S, Djouhri L, et al. Expression and properties of hyperpolarization-activated current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons with known sensory function. J Physiol. 2012. October 1;590(19):4691–4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kouranova EV, Strassle BW, Ring RH, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mRNA and protein expression in large versus small diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons: correlation with hyperpolarization-activated current gating. Neuroscience. 2008. June 2;153(4):1008–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Momin A, Cadiou H, Mason A, et al. Role of the hyperpolarization-activated current Ih in somatosensory neurons. J Physiol. 2008. December 15;586(24):5911–5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lainez S, Tsantoulas C, Biel M, et al. HCN3 ion channels: roles in sensory neuronal excitability and pain. J Physiol. 2019. September;597(17):4661–4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dini L, Del Lungo M, Resta F, et al. Selective blockade of HCN1/HCN2 channels as a potential pharmacological strategy against pain. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Resta F, Micheli L, Laurino A, et al. Selective HCN1 block as a strategy to control oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy. Neuropharmacology. 2018. March 15;131:403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Francois-Moutal L, Scott DD, Perez-Miller S, et al. Chemical shift perturbation mapping of the Ubc9-CRMP2 interface identifies a pocket in CRMP2 amenable for allosteric modulation of Nav1.7 channels. Channels (Austin). 2018;12(1):219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Moutal A, Yang X, Li W, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of Nf1 gene identifies CRMP2 as a therapeutic target in neurofibromatosis type 1-related pain that is reversed by (S)-Lacosamide. Pain. 2017. December;158(12):2301–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Djouhri L, Dawbarn D, Robertson A, et al. Time course and nerve growth factor dependence of inflammation-induced alterations in electrophysiological membrane properties in nociceptive primary afferent neurons. J Neurosci. 2001. November 15;21(22):8722–8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009. October 16;139(2):267–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hucho T, Levine JD. Signaling pathways in sensitization: toward a nociceptor cell biology. Neuron. 2007. August 2;55(3):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cheng JK, Ji RR. Intracellular signaling in primary sensory neurons and persistent pain. Neurochem Res. 2008. October;33(10):1970–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Acosta C, McMullan S, Djouhri L, et al. HCN1 and HCN2 in Rat DRG neurons: levels in nociceptors and non-nociceptors, NT3-dependence and influence of CFA-induced skin inflammation on HCN2 and NT3 expression. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Smith T, Al Otaibi M, Sathish J, et al. Increased expression of HCN2 channel protein in L4 dorsal root ganglion neurons following axotomy of L5- and inflammation of L4-spinal nerves in rats. Neuroscience. 2015. June 4;295:90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Papp I, Hollo K, Antal M. Plasticity of hyperpolarization-activated and cyclic nucleotid-gated cation channel subunit 2 expression in the spinal dorsal horn in inflammatory pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2010. October;32(7):1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Jiang YQ, Xing GG, Wang SL, et al. Axonal accumulation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels contributes to mechanical allodynia after peripheral nerve injury in rat. Pain. 2008. July 31;137(3):495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu Y, Feng Y, Zhang T. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment enhances dorsal root ganglion expression of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Mol Neurosci. 2015. September;57(1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cho HJ, Staikopoulos V, Furness JB, et al. Inflammation-induced increase in hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated channel protein in trigeminal ganglion neurons and the effect of buprenorphine. Neuroscience. 2009. August 18;162(2):453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Forster LA, Jansen LR, Rubaharan M, et al. Alterations in SUMOylation of the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated ion channel 2 during persistent inflammation. Eur J Pain. 2020. May 23;24:1517–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Li WM, Cui KM, Li N, et al. Analgesic effect of electroacupuncture on complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced inflammatory pain in mice: a model of antipain treatment by acupuncture in mice. Jpn J Physiol. 2005. December;55(6):339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Millan MJ, Czlonkowski A, Morris B, et al. Inflammation of the hind limb as a model of unilateral, localized pain: influence on multiple opioid systems in the spinal cord of the rat. Pain. 1988. December;35(3):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Further confirmation of the role of adenyl cyclase and of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in primary afferent hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 1991;44(1):131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Resta F, Masi A, Sili M, et al. Kynurenic acid and zaprinast induce analgesia by modulating HCN channels through GPR35 activation. Neuropharmacology. 2016. September;108:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Malmberg AB, Brandon EP, Idzerda RL, et al. Diminished inflammation and nociceptive pain with preservation of neuropathic pain in mice with a targeted mutation of the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 1997. October 1;17(19):7462–7470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Herrmann S, Rajab H, Christ I, et al. Protein kinase A regulates inflammatory pain sensitization by modulating HCN2 channel activity in nociceptive sensory neurons. Pain. 2017. October;158(10):2012–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Djouhri L, Al Otaibi M, Kahlat K, et al. Persistent hindlimb inflammation induces changes in activation properties of hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in rat C-fiber nociceptors in vivo. Neuroscience. 2015. August;20(301):121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nawathe PA, Kryukova Y, Oren RV, et al. An LQTS6 MiRP1 mutation suppresses pacemaker current and is associated with sinus bradycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013. September;24(9):1021–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Qu J, Kryukova Y, Potapova IA, et al. MiRP1 modulates HCN2 channel expression and gating in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004. October 15;279(42):43497–43502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Brandt MC, Endres-Becker J, Zagidullin N, et al. Effects of KCNE2 on HCN isoforms: distinct modulation of membrane expression and single channel properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009. July;297(1):H355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kimura K, Kitano J, Nakajima Y, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated HCN2 cation channel forms a protein assembly with multiple neuronal scaffold proteins in distinct modes of protein-protein interaction. Genes Cells. 2004. July;9(7):631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Santoro B, Wainger BJ, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of HCN channel surface expression by a novel C-terminal protein-protein interaction. J Neurosci. 2004. November 24;24(47):10750–10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Michels G, Er F, Khan IF, et al. K+ channel regulator KCR1 suppresses heart rhythm by modulating the pacemaker current If. PLoS One. 2008. January 30;3(1):e1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Flotho A, Melchior F. Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:357–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Hendriks IA, D’Souza RC, Chang JG, et al. System-wide identification of wild-type SUMO-2 conjugation sites. Nat Commun. 2015. June 15;6:7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Parker AR, Welch MA, Forster LA, et al. SUMOylation of the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 2 increases surface expression and the maximal conductance of the hyperpolarization-activated current. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;9:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wang Y, Gao Y, Tian Q, et al. Author correction: TRPV1 SUMOylation regulates nociceptive signaling in models of inflammatory pain. Nat Commun. 2018. June 28;9(1):2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Dustrude ET, Moutal A, Yang X, et al. Hierarchical CRMP2 posttranslational modifications control NaV1.7 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016. December 27;113(52):E8443–E8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Parker AR, Forster LA, Baro DJ. Modulator-gated, SUMOylation-mediated, activity-dependent regulation of ionic current densities contributes to short-term activity homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2019. January 23;39(4):596–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rigaud M, Gemes G, Barabas ME, et al. Species and strain differences in rodent sciatic nerve anatomy: implications for studies of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008. May;136(1–2):188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Swett JE, Torigoe Y, Elie VR, et al. Sensory neurons of the rat sciatic nerve. Exp Neurol. 1991. October;114(1):82–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Salo PT, Theriault E. Number, distribution and neuropeptide content of rat knee joint afferents. J Anat. 1997. May;190(Pt 4):515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Nakajima T, Ohtori S, Inoue G, et al. The characteristics of dorsal-root ganglia and sensory innervation of the hip in rats. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008. February;90(2):254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Herrity AN, Rau KK, Petruska JC, et al. Identification of bladder and colon afferents in the nodose ganglia of male rats. J Comp Neurol. 2014. November 1;522(16):3667–3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Belkouch M, Dansereau MA, Tetreault P, et al. Functional up-regulation of Nav1.8 sodium channel in Abeta afferent fibers subjected to chronic peripheral inflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2014. March 7;11:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Koltzenburg M, Wall PD, McMahon SB. Does the right side know what the left is doing? Trends Neurosci. 1999. March;22(3):122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Welch MA, Forster LA, Atlas SI, et al. SUMOylating two distinct sites on the A-type potassium channel, Kv4.2, Increases surface expression and decreases current amplitude [Original Research]. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019. May 31;12(144). DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Steffensen AB, Andersen MN, Mutsaers N, et al. SUMO co-expression modifies K V 11.1 channel activity. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2018. March;222(3):e12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Xiong D, Li T, Dai H, et al. SUMOylation determines the voltage required to activate cardiac IKs channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. August 8;114(32):E6686–E6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Plant LD, Dementieva IS, Kollewe A, et al. One SUMO is sufficient to silence the dimeric potassium channel K2P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010. June 8;107(23):10743–10748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Benson MD, Li QJ, Kieckhafer K, et al. SUMO modification regulates inactivation of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007. February 6;104(6):1805–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Plant LD, Marks JD, Goldstein SA. SUMOylation of NaV1.2 channels mediates the early response to acute hypoxia in central neurons. Elife. 2016. December 28;5. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.20054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Dai XQ, Kolic J, Marchi P, et al. SUMOylation regulates Kv2.1 and modulates pancreatic beta-cell excitability. J Cell Sci. 2009. March 15;122(Pt6):775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Seifert A, Schofield P, Barton GJ, et al. Proteotoxic stress reprograms the chromatin landscape of SUMO modification. Sci Signal. 2015. July 7;8(384):rs7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Dustrude ET, Wilson SM, Ju W, et al. CRMP2 protein SUMOylation modulates NaV1.7 channel trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2013. August 23;288(34):24316–24331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Francois-Moutal L, Dustrude ET, Wang Y, et al. Inhibition of the Ubc9 E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme-CRMP2 interaction decreases NaV1.7 currents and reverses experimental neuropathic pain. Pain. 2018. October;159(10):2115–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Largent-Milnes TM, Dustrude ET, Largent-Milnes TM, et al. Blocking CRMP2 SUMOylation reverses neuropathic pain. Mol Psychiatry. 2017. May 23;23:1745–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Qi Y, Wang J, Bomben VC, et al. Hyper-SUMOylation of the Kv7 potassium channel diminishes the M-current leading to seizures and sudden death. Neuron. 2014. September 3;83(5):1159–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Plant LD, Dowdell EJ, Dementieva IS, et al. SUMO modification of cell surface Kv2.1 potassium channels regulates the activity of rat hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2011. May;137(5):441–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Rajan S, Plant LD, Rabin ML, et al. Sumoylation silences the plasma membrane leak K+ channel K2P1. Cell. 2005. April 8;121(1):37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Plant LD, Xiong D, Romero J, et al. Hypoxia produces pro-arrhythmic late sodium current in cardiac myocytes by SUMOylation of NaV1.5 channels. Cell Rep. 2020. February 18;30(7):2225–2236e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]